Abstract

Negative affect and loss-of-control (LOC)-eating are consistently linked and prevalent among youth identifying as non-Hispanic Black (NHB) and non-Hispanic White (NHW), particularly those with high weight. Given health disparities in high weight and associated cardiometabolic health concerns among NHB youth, elucidating how the association of negative affect with adiposity may vary by racial/ethnic group, and whether that relationship is impacted by LOC-eating, is warranted. Social inequities and related stressors are associated with negative affect among NHB youth, which may place this group at increased risk for excess weight gain. Across multiple aggregated protocols, 651 youth (13.0±2.7y; 65.9% girls, 40.7% NHB; 1.0±1.1 BMIz; 37.6% LOC-eating) self-reported trait anxiety and depressive symptoms as facets of negative affect. LOC-eating was assessed by interview and adiposity was measured objectively. Cross-sectional moderated mediation models predicted adiposity from ethno-racial identification (NHB, NHW) through the pathway of anxiety or depressive symptoms and examined whether LOC-eating influenced the strength of the pathway, adjusting for SES, age, height, and sex. The association between ethno-racial identity and adiposity was partially mediated by both anxiety (95% CI = [.01, .05]) and depressive symptoms (95% CI = [.02, .08]), but the mediation was not moderated by LOC-eating for either anxiety (95% CI = [−.04, .003]) or depressive symptoms (95% CI = [−.07, .03]). Mechanisms underlying the link between negative affect and adiposity among NHB youth, such as stress from discrimination and stress-related inflammation, should be explored. These data highlight the need to study impacts of social inequities on psychosocial and health outcomes.

Keywords: Negative affect, loss-of-control eating, adiposity, sociocultural factors, ethno-racial identity

1. Introduction

Loss-of-control (LOC)-eating, the key feature of binge-eating disorder that involves the subjective experience of being out of control while eating, has been robustly linked to pediatric obesity (Byrne et al., 2019; He et al., 2016). Research has established cross-sectional (e.g. Shomaker et al., 2010) and prospective (Sonneville et al., 2013; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2009) links between LOC-eating and excess weight gain. LOC-eating has also been shown to contribute to the development of exacerbated disordered eating behaviors and psychological distress (Hilbert et al., 2013; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2011). According to affect theory, LOC-eating may develop as a result of maladaptive coping with negative emotions, such as anxiety and depressed mood (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991; Kenardy et al., 1996). Negative affect has been established cross-sectionally as both a risk and maintenance factor for LOC-eating based on interview reports (Goldschmidt et al., 2008; Shomaker et al., 2010), in laboratory feeding paradigms (Ranzenhofer et al., 2013), as well as prospectively (Stice, 2002). These data support the notion that negative affect influences LOC-eating and subsequent weight gain. Some (Dallman, 2010; Diggins et al., 2015; Fowler-Brown et al., 2009), but not all (Istvan et al., 1992; McElroy et al., 2004) research has also demonstrated a link between greater negative affect and adiposity among youth.

Although the links among negative affect, LOC-eating, and weight have been well-established (Goldschmidt et al., 2008; Shomaker et al., 2010; Stice, 2002), how these relationships may be influenced by critically important social factors, such as membership in certain racial/ethnic groups, remains unclear. Specific sociodemographic groups in the United States are at increased risk for excess weight gain and associated health consequences. Indeed, youth identifying as non-Hispanic Black (NHB) in the United States demonstrate higher rates of overweight, obesity (Ogden et al., 2020), and associated adverse emotional (Pickett et al., 2020) and health concerns (Pi-Sunyer, 2002) compared to youth identifying as non-Hispanic White (NHW). Given the prevalence of these weight and health disparities, better understanding the interplay with key affective factors is necessary to inform prevention and treatment efforts for youth at risk for adverse health outcomes.

While it is well-established that youth identifying as NHB and NHW do not differ physiologically (American Medical Association, 2020; Flanagin et al., 2021), ethno-racial identification is best viewed as a construct that carries direct and indirect social stressors that consistently predict psychosocial and health outcomes (Browne et al., 2022). Structural racism and the resulting social inequity and related stressors, including discrimination, chronic stress, and social isolation (Brody et al., 2006; Kumanyika et al., 2007; Lambert et al., 2009; Liburd, 2003; Pickett et al., 2020; Sue et al., 2007) are associated with facets of negative affect, such as anxiety and depression, among youth identifying as NHB. The literature is mixed regarding whether rates of binge and LOC-eating do in fact differ between youth identifying as NHB and NHW (Story et al., 1995; Swanson et al., 2011), with most studies (Austin et al., 2008; Cassidy et al., 2012; Glasofer et al., 2007; Pernick et al., 2006) suggesting that rates of LOC-eating are similar between groups. It is possible that LOC-eating may exacerbate risk for weight gain even further and could have implications for NHB youth’s subsequent eating pathology and health outcomes.

The current study aimed to examine pathways between ethno-racial identification, negative affect, LOC-eating, and adiposity. First, a cross-sectional mediation model will be tested between the constructs of ethno-racial identification (referred to hereafter as ‘racial identity’), negative affect (i.e., trait anxiety and depressive symptoms), and adiposity to determine whether racial identity may contribute to adiposity indirectly through negative affect for youth identifying as NHB. Next, if hypothesized links between racial identity, negative affect, and adiposity are present, a moderated mediation model will determine whether LOC-eating impacts the strength of the indirect effect of negative affect on the link between racial identification and adiposity. More specifically, within the simple cross-sectional mediation framework, it was hypothesized that 1) there will be a significant association between racial identity and adiposity, 2) youth identifying as NHB would report higher levels of negative affect (i.e., anxiety and depressive symptoms) compared to youth identifying as NHW, 3) higher levels of negative affect would be related to higher adiposity, and 4) the relationship between racial identity and adiposity would be partially explained through an indirect pathway of negative affect. Within a moderated mediation framework, it was expected that 1) there will be a significant association between racial identity and adiposity, 2) youth identifying as NHB youth would exhibit higher levels of negative affect compared to youth identifying as NHW, 3) higher levels of negative affect would be related to higher adiposity, and 4) LOC-eating would moderate the link between negative affect and adiposity, such that youth with LOC-eating would have a more robust association between negative affect and adiposity, and the presence of LOC-eating will strengthen the indirect effect of negative affect on the link between racial identity and adiposity.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

A convenience sample of participants was assembled from seven aggregated protocols conducted at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) between June 1996 and August 2022 examining eating behaviors and childhood obesity. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the NICHD or USUHS. Three of the protocols involved interventions focused on reducing psychological factors that promote excess weight gain (ClinicalTrials.gov IDs: NCT00263536; NCT00680979; NCT01425905) and four were observational nontreatment protocols (ClinicalTrials.gov IDs: NCT00001522; NCT00320177; NCT00631644; NCT02390765). For intervention protocols (NCT00263536; NCT00680979; NCT01425905), the current study only utilized baseline data, prior to treatment. All participants were youth between the ages of 7–18 years old in generally good health with a BMI ≥ 5th percentile. Given only 8% and 8.5% of youth reported multiple racial identities or Hispanic or Latino ethnic identity, respectively, samples sizes were not large enough to analyze these racial and ethnic identities separately, thus only youth identifying as NHB and NHW were included. Youth were excluded for any major medical illness, substance abuse or psychiatric illness that may have impacted participation, or use of any medication or therapy that may have impacted their weight. Several protocols included in the current sample had LOC-eating (NCT00680979) or risk for excess weight gain/overweight or obesity (NCT00263536, NCT01425905) as inclusion criteria, or were enriched for LOC-eating presence (NCT00320177). An exclusion criterion for all protocols was history of an eating disorder or current eating disorder other than binge-eating disorder (BED). Participants found to have an eating disorder other than BED at baseline screening were referred for specialized treatment.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Child’s sex assigned at birth and ethno-racial identification were self-reported or reported by their parents. Parents reported their education level and employment status using the Hollingshead Index (Hollingshead, 1975) to assess socioeconomic status (SES). The Hollingshead Index ranges from 1 to 5, with lower scores indicating a higher SES. As per prior literature (Cassidy et al., 2012), SES scores were dichotomized for analyses and were recoded as “1” for scores 1 to 3 to indicate “higher” SES, or “0” for scores 4 to 5 to indicate “lower” SES.

2.2.2. Anthropometric Measures

Height was measured in triplicate by a stadiometer, and fasting weight was measured by a scale calibrated to the nearest 0.1 kg to calculate BMI (kg/m2). BMIz scores, normed for age and sex, were then computed according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention growth standards (Kuczmarski et al., 2002). Depending on the protocol, fat mass (kg) was objectively measured by either air displacement plethysmography (Bod Pod; Life Measurement Inc., Concord, CA) or dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA; iDXA system, GE Healthcare, Madison WI), and analyzed with GE Encore 15, SP 2 software. Adiposity was adjusted to ensure equivalence between techniques by multiplying girls’ Bod Pod fat percentage by 1.03 (Nicholson et al., 2001).

2.2.3. Eating Disorder Examination

The Eating Disorder Examination adult (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) or child (Bryant-Waugh et al., 1996) version was administered to participants in order to measure the presence of LOC-eating within the past one month. The Eating Disorder Examination is a semi-structured psycho-diagnostic interview of eating disorder psychopathology. The Eating Disorder Examination contains 21 items that assess disordered attitudes and behaviors related to eating, body-shape and weight, and 13 items (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) designed and adapted to diagnose specific DSM-5 eating disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). The Eating Disorder Examination has demonstrated sound psychometric properties, including good to excellent test-retest and interrater reliability in youth across the weight spectrum (Glasofer et al., 2007; Rizvi et al., 2000), as well as individuals from diverse racial/ethnic identity backgrounds (Burke, Tanofsky-Kraff, et al., 2017; Grilo et al., 2015). The child version of Eating Disorder Examination (Bryant-Waugh et al., 1996) has demonstrated good to excellent interrater reliability (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004; Watkins et al., 2005) and good internal consistency and discriminant validity among youth (Watkins et al., 2005). Training and administration for the Eating Disorder Examination is described elsewhere (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004).

2.2.4. Self-Report Questionnaires

2.2.4.1. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, Trait subscale

Participants self-reported trait anxiety using the 20-item State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, trait subscale (Spielberger, 1973). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, trait subscale demonstrates good psychometric properties, including good reliability and construct validity in general (Papay & Hedl Jr, 1978) as well as good reliability and validity in samples identifying with diverse racial/ethnic identity backgrounds (Brown & Duren, 1988; Novy et al., 1993). The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children, trait subscale total score is calculated by a sum of all items rated on a 3-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater trait anxiety, with total scores ranging from 20–60. Internal consistency of the trait subscale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children in the current study was high for the total sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .88), and Cronbach’s alpha exceeded .87 in both racial identity groups.

2.2.4.2. Children’s Depression Inventory

Participants self-reported depressive symptoms over the past two weeks using the Children’s Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (Kovacs, 1992). The Children’s Depression Inventory is a 27-item self-report measure that assesses the presence and degree of childhood depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Total scores were used for current analyses. Items are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 2, with total scores ranging from 0 to 54. Greater scores indicate greater depressive symptoms, with a “clinical cutoff” of 19 (Kovacs, 1992). The Children’s Depression Inventory has shown high internal consistency in pediatric samples (Stiensmeier-Pelster et al., 2000) and consistent psychometric properties for item-level and total scores between samples identifying as NHB and NHW (Steele et al., 2006). Notably, one protocol in the aggregated sample did not administer the Children’s Depression Inventory and as such, those participants were not included in the analyses with depressive symptoms. Internal consistency of the Children’s Depression Inventory in the current study was high for the total sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .86), and Cronbach’s alpha exceeded .85 in both racial identity groups.

2.3. Data Analytic Plan

2.3.1. Missing Data

Missing data were analyzed and multiply imputed using the mice package in R. No more than 6.5% of data were missing for any variable, other than depressive symptoms. Given that one of the studies in the aggregated dataset did not administer the Children’s Depression Inventory, 17.6% of the total dataset had missing values for depressive symptoms. As per multiple imputation guidelines for missing data threshold of approximately 5% (Schafer, 1999), depressive symptom data were not imputed, and the final sample size for analyses with depressive symptoms was N=536. All other analyses included the complete multiply imputed dataset sample size of N=651.

2.3.2. Statistical Models

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All variables were screened for outliers, skew, and kurtosis. Two primary variables of interest, depressive symptoms and adiposity, were not normally distributed within the overall sample, and were thus natural-log transformed to meet the assumptions necessary for analyses. No influential outliers were identified. LOC-eating severity was considered as a continuous variable in the model, however given the highly skewed and restricted range of LOC-eating episodes in the combined current sample, this variable was not able to be examined continuously and was thus analyzed as a categorical variable of LOC-eating presence or absence. While a latent construct of negative affect was considered for analyses in order to capture the shared contribution of anxiety and depressive symptoms on outcomes, anxiety and depressive symptoms were analyzed separately due to the clinical value of distinguishing between different affective states as well as past literature that has found these particular negative mood states to be differentially associated with LOC-eating (Shank et al., 2017). Independent samples t-tests or Pearson’s chi-square test, as appropriate, were conducted to compare relevant covariates between sociodemographic groups. Youth identifying as NHB were coded = 1 to serve as the reference group for all analyses.

Cross-sectional mediation and moderated mediation models with bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) were conducted using the Preacher and Hayes PROCESS macro v4.1 (Hayes, 2017) for SPSS. Models predicted adiposity as the dependent variable from sociodemographic group (NHB, NHW) as the independent variable. Anxiety and depressive symptoms were analyzed separately as mediators. LOC-eating was included as a moderator of the pathway between negative affect and adiposity for the moderated mediation models. Continuous variables were mean-centered for mediation analyses. All mediation analyses were adjusted for SES (recoded as “1” for scores 1 to 3, or “0” for scores 4 to 5), age, height, and sex. Adjustment for type of study (i.e., observational vs. intervention) was considered, but did not significantly contribute to models upon exploration, and was thus not included as a covariate in final analyses.

Simple cross-sectional mediation models were first conducted to examine the relationship between 1) racial identity and negative affect (a pathway), 2) the relationship between negative affect and adiposity (b pathway), and 3) the indirect mediation through anxiety or depressive symptoms (ab pathway) with 10,000 resamples estimating the 95% bias-corrected CI. Subsequently, within a moderated mediation model framework, LOC-eating was included as a moderator of the relationship between negative affect (anxiety or depressive symptoms) and adiposity (b pathway), and the index of moderated mediation was examined to determine whether LOC-eating influenced the strength of the indirect mediation pathway between racial identity and adiposity.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The total sample included N=651 youth (40.7% NHB; 65.9% girls; 37.6% with LOC-eating in the past month; 2.2% with presence of BED based on at least one episode of binge-eating per week over the past 3 months; BMIz 1.0±1.1) with an average age of 13.0 ±2.7 years. See Table 1 for sample characteristics. Of the total sample, 36.5% met criteria for obesity based on a BMI percentile greater than or equal to the 95th percentile, 24.0% met criteria for overweight based on a BMI percentile less than the 95th percentile and greater than or equal to the 85th percentile, and 39.6% of the sample met criteria for normal weight based on a BMI percentile greater than the 5th percentile and less than the 85th percentile. Results showed that youth identifying as NHB were significantly older (p=.02), had a greater proportion of girls (p<.01), and had higher adiposity (p<.01), higher BMIz (p<.01), and lower SES (p<.01) in the current sample compared to youth identifying as NHW. Presence of LOC-eating did not differ significantly between sociodemographic groups (p=.06).

Table 1. Sample Characteristics.

| Total Sample (N=651) | NHB (N=265) | NHW (N=386) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M±SD) | 13.0±2.7 | 13.3±2.8 | 12.8±2.7 | .02* |

| Sex (% Girls) | 65.9 | 77.0 | 58.3 | <.01* |

| Hollingshead SES (%) | <.01* | |||

| 1 | 21.7 | 11.3 | 28.8 | |

| 2 | 32.4 | 24.2 | 38.1 | |

| 3 | 32.1 | 40.4 | 26.4 | |

| 4 | 12.4 | 20.8 | 6.7 | |

| 5 | 1.4 | 3.4 | 0.0 | |

| BMIz (M±SD) | 1.0±1.1 | 1.5±0.9 | 0.7±1.0 | <.01* |

| Adiposity, kg (M±SD) | 21.1±14.7 | 26.2±16.9 | 17.6±11.8 | <.01* |

| LOC-eating Presence (%) | 37.6 | 41.9 | 34.7 | .06 |

Note: NHB = Non-Hispanic Black; NHW = Non-Hispanic White; SES = socioeconomic status; BMIz = body mass index z-score; LOC-eating = loss-of-control eating;

Significant at p < .05.

3.2. Mediation Models

3.2.1. Simple Cross-Sectional Mediation Models

3.2.1.1. Relationship Between Racial Identity and Adiposity Mediated by Trait Anxiety

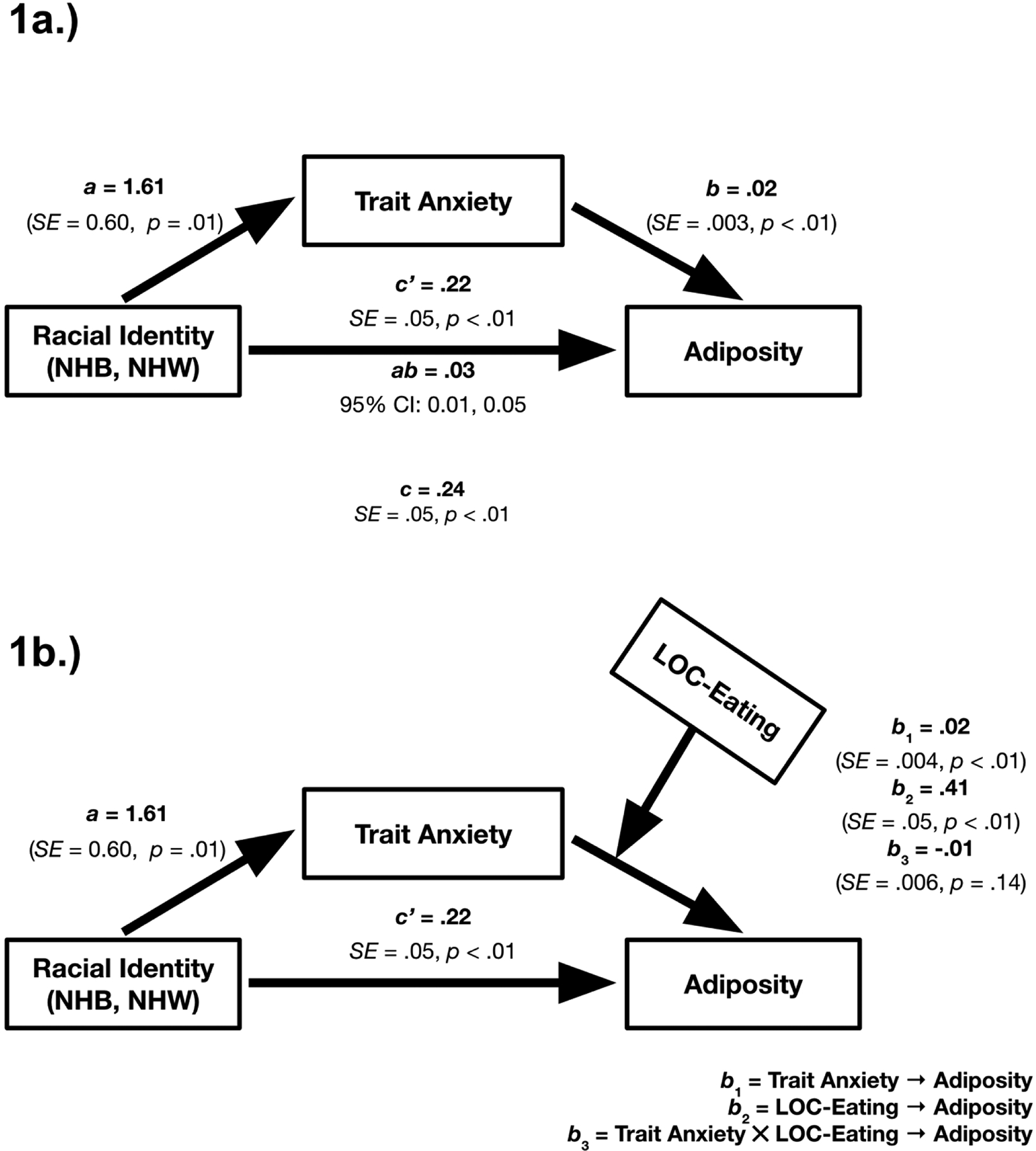

Racial identity was significantly associated with trait anxiety (a = 1.61, SE = 0.60, p = .01) with higher trait anxiety seen in youth identifying as NHB vs NHW. Trait anxiety was significantly positively associated with adiposity (b = .02, SE = 0.003, p < .01). Trait anxiety significantly mediated the association between racial identity and adiposity (ab = 0.03, SE = 0.01, unstandardized 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05]) for a partial mediation effect given the direct effect between racial identity and adiposity remained significant (c’ = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < .01) while accounting for the indirect pathway through anxiety (Figure 1a).

Figure 1:

Trait Anxiety Mediation Analyses Predicting Adiposity. 1a) Trait anxiety significantly mediated the relationship between ethno-racial identity (NHB = Non-Hispanic Black; NHW = Non-Hispanic White) and adiposity. Cross-sectional mediation models with sociodemographic group as the independent variable (NHB = reference group), trait anxiety as the mediator, and adiposity (fat mass, kg) as the dependent variable. The a pathway represents the relationship between ethno-racial identity and trait anxiety, and the b pathway represents the relationship between trait anxiety and adiposity. The c’ pathway represents the direct relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, accounting for trait anxiety. The ab pathway represents the indirect relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, through the trait anxiety pathway. The c pathway represents the total effect (sum of direct and indirect effect) between ethno-racial identity and adiposity. Models adjusted for age, sex, height, and socioeconomic status. 1b) Loss-of-control (LOC)-eating did not significantly moderate the mediation of ethno-racial identity and adiposity through trait anxiety. Cross-sectional mediation models with sociodemographic group as the independent variable (NHB = reference group), trait anxiety as the mediator, LOC-eating as the moderator, and adiposity (fat mass kg) as the dependent variable. The a pathway represents the relationship between ethno-racial identity and trait anxiety. The b1 pathway represents the relationship between trait anxiety and adiposity, the b2 pathway represents the relationship between LOC-eating and adiposity, and the b3 pathway represents the relationship between the interaction of trait anxiety and LOC-eating on adiposity. The c’ pathway represents the direct relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, accounting for trait anxiety. Models adjusted for age, sex, height, and socioeconomic status.

3.2.1.2. Relationship Between Racial Identity and Adiposity Mediated by Depressive Symptoms

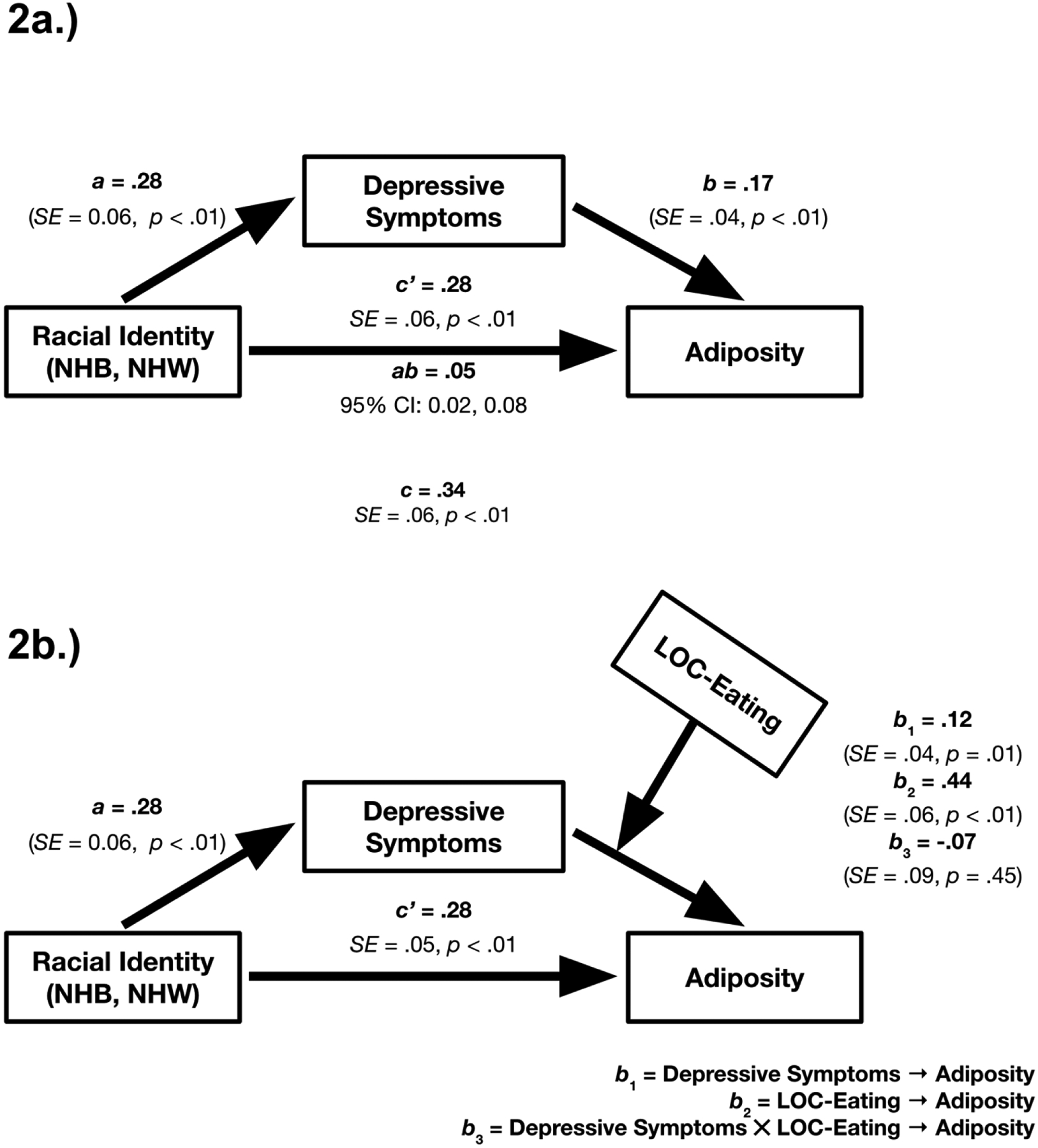

Racial identity was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (a = 0.28, SE = 0.60, p < .01) with higher depressive symptoms seen in youth identifying as NHB vs NHW. Depressive symptoms were significantly positively associated with adiposity (b = 0.04, SE = 0.04, p < .01). Depressive symptoms significantly mediated the association between racial identity and adiposity (ab = 0.05, SE = 0.02, unstandardized 95% CI = [0.02, 0.08]) for a partial mediation effect given the direct effect between racial identity and adiposity remained significant (c’ = 0.28, SE = 0.06, p < .01) while accounting for the indirect pathway through depressive symptoms (Figure 2a).

Figure 2:

Depressive Symptom Mediation Analyses Predicting Adiposity. 2a) Depressive symptoms significantly mediated the relationship between ethno-racial identity (NHB = Non-Hispanic Black; NHW = Non-Hispanic White) and adiposity. Cross-sectional mediation models with sociodemographic group as the independent variable (NHB = reference group), depressive symptoms as the mediator, and adiposity (fat mass, kg) as the dependent variable. The a pathway represents the relationship between ethno-racial identity and depressive symptoms, and the b pathway represents the relationship between depressive symptoms and adiposity. The c’ pathway represents the direct relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, accounting for depressive symptoms. The ab pathway represents the indirect relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, through the depressive symptoms pathway. The c pathway represents the total effect (sum of direct and indirect effect) between ethno-racial identity and adiposity. Models adjusted for age, sex, height, and socioeconomic status. 2b) Loss-of-control (LOC)-eating did not significantly moderate the mediation of ethno-racial identity and adiposity through depressive symptoms. Cross-sectional mediation models with sociodemographic group as the independent variable (NHB = reference group), depressive symptoms as the mediator, LOC-eating as the moderator, and adiposity (fat mass kg) as the dependent variable. The a pathway represents the relationship between ethno-racial identity and depressive symptoms. The b1 pathway represents the relationship between depressive symptoms and adiposity, the b2 pathway represents the relationship between LOC-eating and adiposity, and the b3 pathway represents the relationship between the interaction of depressive symptoms and LOC-eating on adiposity. The c’ pathway represents the direct relationship between ethno-racial identity and adiposity, accounting for depressive symptoms. Models adjusted for age, sex, height, and socioeconomic status.

3.2.2. Moderated Mediation Models

3.2.2.1. Trait Anxiety Mediation Moderated by LOC-Eating

Racial identity remained significantly associated with trait anxiety (a = 1.61, SE = 0.60, p = .01) with higher trait anxiety seen in youth identifying as NHB vs NHW. The direct effect between racial identity and adiposity remained significant (c’ = 0.22, SE = 0.05, p < .01) while accounting for the indirect pathway through trait anxiety. Trait anxiety (b1 = 0.01, SE = .004, p < .01) and LOC-eating (b2 = 0.41, SE = .05, p < .01) were significantly associated with adiposity, but the interaction effect of anxiety by LOC-eating was not significantly associated with adiposity (b3 = −0.01, SE = .006, p = .14). The index of moderated mediation was not significant given the CI contained zero (95% CI = [−.04, .003]), suggesting that LOC-eating did not significantly moderate the indirect effect (Figure 1b).

3.2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms Mediation Moderated by LOC-Eating

Racial identity remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms (a = 0.28, SE = 0.06, p < .01) with higher depressive symptoms seen in youth identifying as NHB vs NHW. The direct effect between racial identity and adiposity remained significant (c’ = 0.28, SE = 0.05, p < .01) while accounting for the indirect pathway through depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms (b1 = 0.12, SE = .04, p = .01) and LOC-eating (b2 = 0.44, SE = .06, p < .01) were significantly associated with adiposity, but the interaction effect of depressive symptoms by LOC-eating was not significantly associated with adiposity (b3 = −0.07, SE = .09, p = .45). The index of moderated mediation was not significant given the CI contained zero (95% CI = [−.07, .03]), suggesting that LOC-eating did not significantly moderate the indirect effect (Figure 2b).

4. Discussion

Among a large convenience sample of youth identifying as NHB and NHW across the weight spectrum, facets of negative affect may play a role in explaining greater adiposity for youth identifying as NHB. Both trait anxiety and depressive symptoms appeared to partially explain higher adiposity among youth identifying as NHB. Contrary to hypotheses, LOC-eating did not interact with facets of negative affect to predict adiposity and did not moderate the mediation by strengthening the indirect pathway between racial identity and adiposity through negative affect. If replicated prospectively, these cross-sectional data may provide a foundation for better understanding potential affective mechanisms for the development of obesity among youth identifying as NHB who are at high-risk for greater anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Findings from the current study are consistent with prior research (Brody et al., 2006; Lambert et al., 2009) and support the hypothesis that youth identifying as NHB may be at heightened risk for greater anxiety and depressive symptoms. This pattern is not surprising given the stress associated with social inequities (Lambert et al., 2009; Pickett et al., 2020; Sue et al., 2007). Findings also replicate some (Dallman, 2010; Diggins et al., 2015; Fowler-Brown et al., 2009), but not all (Istvan et al., 1992; McElroy et al., 2004) research that has demonstrated a link between greater negative affect and adiposity among youth. Notably, we found that the relationship between racial identity and adiposity was mediated through the pathway of negative affect, placing NHB youth at increased risk for high weight. Social disparities and discrimination due to marginalized identities can trigger prolonged, repeated activation of physiological stress responses, which increase one’s risk for metabolic alterations and adverse obesity-related health outcomes (Browne et al., 2022; Timper & Brüning, 2017). If replicated in prospective designs, this may be one mechanism that contributes to excess weight gain among youth identifying as NHB through the pathway of experiences that increase negative affect. Given the data are cross-sectional, reciprocal relationships should be considered between continuous variables of adiposity and negative affect as well. High weight may further increase NHB youth’s exposure to discrimination due to weight stigma (Puhl et al., 2020; Vartanian & Porter, 2016), and thus adiposity may, in turn, contribute to exacerbated negative affect due to intersecting marginalized identities (Garnett et al., 2014; Patil et al., 2018). Indeed, it has been shown that youth who experience intersectional discrimination on the basis of racial identity or weight-related stigma report greater emotional distress (Garnett et al., 2014; Patil et al., 2018).

LOC-eating did not significantly moderate the mediation effects of negative affect on adiposity, contrary to hypotheses. This lack of interactive findings for LOC-eating and negative affect on adiposity in the mediation model suggests that, although there are well-established links between negative affect, LOC-eating, and adiposity independently (Byrne et al., 2019; Ranzenhofer et al., 2013; Shomaker et al., 2010; Stice, 2002; Tanofsky-Kraff, 2008), these constructs do not appear to interact to exacerbate adiposity. Consistent with prior research on weight (Ogden et al., 2020) and LOC-eating frequency (Austin et al., 2008; Cassidy et al., 2012; Glasofer et al., 2007; Pernick et al., 2006), group comparisons in the current study did indeed find higher adiposity among youth identifying as NHB compared to NHW, as well as similar rates of LOC-eating between youth identifying as NHB and NHW. These findings may lend evidence to the notion that LOC-eating does not play a salient role in higher adiposity among youth identifying as NHB. However, findings were somewhat surprising because at least one study has shown greater energy consumption among youth identifying as NHB with reported LOC-eating compared with their NHW peers (Cassidy et al., 2012). It may be possible that LOC-eating severity, measured continuously instead of categorically as in the current study, influences the strength of the indirect relationship between racial identity and adiposity through negative affect. However, given the highly skewed and restricted range of episodes in the current sample, LOC-eating was not able to be examined as a continuous moderator or mediator.

Current findings perhaps suggest that factors above and beyond the interaction of negative affect and LOC-eating may be more pertinent to risk for excess weight gain among youth identifying as NHB. Indeed, research has reported that youth identifying as NHB and their families view LOC-eating as a consequence of psychological distress arising from aspects of structural racism (Cassidy et al., 2018; Cassidy et al., 2013). Although not directly measured in the current study, social inequities and related stressors disproportionately impact NHB communities (Brody et al., 2006; Kumanyika et al., 2007; Lambert et al., 2009; Liburd, 2003; Pickett et al., 2020; Sue et al., 2007). These structural, environmental, and cultural factors uniquely impacting youth identifying as NHB are critical to recognize when considering variables above and beyond LOC-eating that likely play an important role in understanding risk for excess weight gain.

Many treatment modalities are not ideally tailored to youth identifying as NHB and their families (Cassidy et al., 2015), and likely lack a nuanced conceptualization of culturally-specific factors influencing excess weight gain among youth identifying as NHB. Unfortunately, research suggests that rates of treatment utilization for prevention of excess weight gain are lower (Coffino et al., 2022) and attrition rates are higher (Dolinsky et al., 2012; Ligthart et al., 2017) among patients identifying as NHB compared to NHW. However, interpersonal psychotherapy, which focuses on reducing mood-induced eating, may be particularly promising for youth identifying as NHB (Burke et al., in press), as it has been consistently shown to resonate with (Cassidy et al., 2018; Cassidy et al., 2013), and may be effective for, reducing long-term risk for excess weight gain (Burke, Shomaker, et al., 2017) among youth identifying as NHB. Notably, findings from one study suggested that LOC-eating may not be necessary or sufficient to target in order to influence adiposity over time (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2017; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2014), which aligns with current findings related to the non-significant interaction of LOC-eating with negative affect on adiposity outcomes for youth identifying as NHB. Of note, this study highlights one approach, which addresses the circumstances Black youth are faced with, but does not address the factors generating these circumstances. Such approaches need to be taken along with concomitant efforts to address and eliminate structural racism in order to improve the health and well-being of youth identifying as NHB.

Strengths of the current study include a large sample size, use of a well-validated semi-structured interview to assess LOC-eating, and objectively collected measurements of adiposity (i.e. DXA or BodPod) (Goran & Treuth, 2001; Kien & Ugrasbul, 2004). Limitations include the use of a convenience sample and the fact that analyses were intentionally restricted to participants identifying as NHB or NHW. As such, findings cannot be generalized to other racial or ethnic identities, or those who identify with multiple racial identities, and these groups should continue to be explored in future studies. Cross-sectional data limit the ability to draw causal relationships between racial identity, negative affect, and adiposity. Additionally, anxiety and depressive symptoms were self-reported and may have been subject to bias. The lack of direct assessments of experiences of discrimination or social stressors, even in a subset of participants within the aggregated study protocols, limits the ability to draw mechanistic conclusions for the observed relationships, and thus any suggested relationships between observed findings and conceptualizations of social inequities should be interpreted with caution. Finally, the effect sizes for significant results were small (Cohen, 1988) for most findings and thus should be interpreted with caution. Other facets of LOC-eating episodes, such as number of episodes or macronutrient content of eating episode, in relation to negative affect and adiposity could be considered in future research. Studies should also examine the effects of these links prospectively, with multiple assessment time-points, to determine whether the trajectory of NHB youth’s negative affect may contribute to development of LOC-eating behaviors and excess weight gain over time.

In conclusion, anxiety and depressive symptoms mediated the link between racial identity and adiposity and may partially explain a pathway for increased risk for internalizing pathology and adverse health outcomes for youth identifying as NHB. Mechanisms to explain these relationships, such as stress from perceived discrimination or stress-related inflammation, should be explored. There is a need to advance multicultural research in the eating and weight fields, with the current study supporting recent calls for improvements in intersectionality-informed approaches to care (Burke et al., 2020; Egbert et al., 2022; Goel et al., 2022) for high-risk individuals. The current findings lend support to the importance of studying impacts of social inequities on psychosocial and health outcomes, as well as the importance of identifying cultural and developmental risk and protective factors when providing tailored, culturally sensitive care.

Highlights.

Trait anxiety and depressive symptoms partially explain higher adiposity among youth identifying as Non-Hispanic Black compared to Non-Hispanic White

Loss-of-control eating did not moderate the mediation pathway

Anxiety and depressive symptoms may partially explain a pathway for increased risk for internalizing pathology and adverse health outcomes for youth identifying as Non-Hispanic Black

Funding:

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant/Award Numbers: 1F32HD056762, K99/R00HD069516, 1ZIAHD000641; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: R01DK080906-04; Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Grant/Award Number: R072IC. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health ZIAMH002781.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of the National Institutes of Health, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the United States Department of Defense.

Declarations of interest: none

References

- American Medical Association. (2020). Elimination of race as a proxy for ancestry, genetics, and biology in medical education, research and clinical practice H-65.953: a policy statement American Medical Association. Retrieved November, 2022 from https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/race?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-H-65.953.xml [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Austin S, Ziyadeh N, Forman S, Prokop L, Keliher A, & Jacobs D (2008). Screening high school students for eating disorders: Results of a national initiative. Preventing Chronic Disease, 5(4). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen YF, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, & Cutrona CE (2006). Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development, 77(5), 1170–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MT, & Duren PS (1988). Construct validity for blacks of the state-trait anxiety inventory. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 21(1), 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Browne NT, Hodges EA, Small L, Snethen JA, Frenn M, Irving SY, Gance-Cleveland B, & Greenberg CS (2022). Childhood obesity within the lens of racism. Pediatric Obesity, 17(5), e12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, & Lask BD (1996). The use of the eating disorder examination with children: A pilot study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 19(4), 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NL, Schaefer LM, Hazzard VM, & Rodgers RF (2020). Where identities converge: The importance of intersectionality in eating disorders research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(10), 1605–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NL, Shomaker LB, Brady S, Reynolds JC, Young JF, Wilfley DE, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, Olsen CH, Yanovski JA, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2017). Impact of age and race on outcomes of a program to prevent excess weight gain and disordered eating in adolescent girls. Nutrients, 9(947), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NL, Shomaker LB, Sbrocco T, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (in press). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for the Prevention of Excess Weight Gain with Adolescent Girls who Identify as Black/African American. In Weissman MM & Mootz J (Eds.), Interpersonal Psychotherapy: A Global Reach. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke NL, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Crosby R, Mehari RD, Marwitz SE, Broadney MM, Shomaker LB, Kelly NR, Schvey NA, Cassidy O, Yanovski SZ, & Yanovski JA (2017). Measurement invariance of the Eating Disorder Examination in black and white children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(7), 758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ME, LeMay-Russell S, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2019). Loss-of-Control Eating and Obesity Among Children and Adolescents. Current Obesity Reports, 8, 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy O, Eichen DM, Burke NL, Patmore J, Shore A, Radin RM, Sbrocco T, Shomaker LB, Mirza N, Young JF, Wilfley DE, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2018). Engaging African American adolescents and stakeholders to adapt interpersonal psychotherapy for weight gain prevention. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(2), 128–161. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy O, Sbrocco T, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2015). Utilising non-traditional research designs to explore culture-specific risk factors for eating disorders in African-American adolescents. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice, 3(1), 91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy O, Sbrocco T, Vannucci A, Nelson B, Jackson-Bowen D, Heimdal J, Mirza N, Wilfley DE, Osborn R, Shomaker LB, Young JF, Waldron H, Carter M, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2013). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for the prevention of excessive weight gain in rural African American girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(9), 965–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy OL, Matheson B, Osborn R, Vannucci A, Kozlosky M, Shomaker LB, Yanovski SZ, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2012). Loss of control eating in African-American and Caucasian youth. Eating Behaviors, 13(2), 174–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffino JA, Ivezaj V, Barnes RD, White MA, Pittman BP, & Grilo CM (2022). Ethnic and racial comparisons of weight-loss treatment utilization history and outcomes in patients with obesity and binge-eating disorder. Eating Behaviors, 44, 101594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. In: Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Dallman MF (2010). Stress-induced obesity and the emotional nervous system. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 21(3), 159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggins A, Woods-Giscombe C, & Waters S (2015). The association of perceived stress, contextualized stress, and emotional eating with body mass index in college-aged Black women. Eating Behaviors, 19, 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolinsky DH, Armstrong SC, & Østbye T (2012). Predictors of attrition from a clinical pediatric obesity treatment program. Clinical Pediatrics, 51(12), 1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbert AH, Hunt RA, Williams KL, Burke NL, & Mathis KJ (2022). Reporting racial and ethnic diversity in eating disorder research over the past 20 years. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(4), 455–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Cooper Z (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination (12th edition). In Fairburn CG & Wilson GT (Eds.), Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. (pp. 317–360). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagin A, Frey T, Christiansen SL, & Committee, A. M. o. S. (2021). Updated guidance on the reporting of race and ethnicity in medical and science journals. JAMA, 326(7), 621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler-Brown AG, Bennett GG, Goodman MS, Wee CC, Corbie-Smith GM, & James SA (2009). Psychosocial stress and 13- year BMI change among blacks: the Pitt County Study. Obesity, 17(11), 2106–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett BR, Masyn KE, Austin SB, Miller M, Williams DR, & Viswanath K (2014). The intersectionality of discrimination attributes and bullying among youth: An applied latent class analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(8), 1225–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, Yanovski SZ, Theim KR, Mirch MC, Ghorbani S, Ranzenhofer LM, Haaga D, & Yanovski JA (2007). Binge eating in overweight treatment-seeking adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32(1), 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel NJ, Jennings Mathis K, Egbert AH, Petterway F, Breithaupt L, Eddy KT, Franko DL, & Graham AK (2022). Accountability in promoting representation of historically marginalized racial and ethnic populations in the eating disorders field: A call to action. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(4), 463–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Jones M, Manwaring JL, Luce KH, Osborne MI, Cunning D, Taylor KL, Doyle AC, Wilfley DE, & Taylor CB (2008). The clinical significance of loss of control over eating in overweight adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(2), 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goran MI, & Treuth MS (2001). Energy expenditure, physical activity, and obesity in children. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 48(4), 931–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Reas DL, Hopwood CJ, & Crosby RD (2015). Factor structure and construct validity of the eating disorder examination- questionnaire in college students: Further support for a modified brief version. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(3), 284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- He J, Cai Z, & Fan X (2016). Prevalence of binge and loss of control eating among children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: An exploratory meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(2), 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, & Baumeister RF (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 86–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Hartmann AS, Czaja J, & Schoebi D (2013). Natural course of preadolescent loss of control eating. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(3), 684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB (1975). Four factor index of social status. Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Istvan J, Zavela K, & Weidner G (1992). Body weight and psychological distress in NHANES I. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 16(12), 999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenardy J, Arnow B, & Agras WS (1996). The aversiveness of specific emotional states associated with binge-eating in obese subjects. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 30(6), 839–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kien CL, & Ugrasbul F (2004). Prediction of daily energy expenditure during a feeding trial using measurements of resting energy expenditure, fat-free mass, or Harris-Benedict equations. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 80(4), 876–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1992). The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. [PubMed]

- Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, & Johnson CL (2002). 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital and health statistics. Series 11, Data from the national health survey(246), 1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S, Whitt-Glover MC, Gary TL, Prewitt TE, Odoms-Young AM, Banks-Wallace J, Beech BM, Hughes-Halbert C, Karanja N, & Lancaster KJ (2007). Expanding the obesity research paradigm to reach African American communities. Preventing Chronic Disease, 4(4), 1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Herman KC, Bynum MS, & Ialongo NS (2009). Perceptions of racism and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents: The role of perceived academic and social control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liburd LC (2003). Food, identity, and African-American women with type 2 diabetes: an anthropological perspective. Diabetes Spectrum, 16(3), 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ligthart KA, Buitendijk L, Koes BW, & van Middelkoop M (2017). The association between ethnicity, socioeconomic status and compliance to pediatric weight-management interventions–a systematic review. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 11(5), 1–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Malhotra S, Nelson EB, Keck PE, & Nemeroff CB (2004). Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(5), 634–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JC, McDuffie JR, Bonat SH, Russell DL, Boyce KA, McCann S, Michael M, Sebring NG, Reynolds JC, & Yanovski JA (2001). Estimation of body fatness by air displacement plethysmography in African American and white children. Pediatric Research, 50(4), 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novy DM, Nelson DV, Goodwin J, & Rowzee RD (1993). Psychometric comparability of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for different ethnic subpopulations. Psychological Assessment, 5(3), 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, Freedman DS, Carroll MD, Gu Q, & Hales CM (2020). Trends in obesity prevalence by race and Hispanic origin—1999–2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA, 324(12), 1208–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papay JP, & Hedl JJ Jr (1978). Psychometric characteristics and norms for disadvantaged third and fourth grade children on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 6(1), 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil PA, Porche MV, Shippen NA, Dallenbach NT, & Fortuna LR (2018). Which girls, which boys? The intersectional risk for depression by race and ethnicity, and gender in the US. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernick Y, Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, Kern M, Ji M, Lawson MJ, & Wilfley D (2006). Disordered eating among a multi-racial/ethnic sample of female high-school athletes. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(6), 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer F (2002). Medical complications of obesity in adults. In Fairburn CG & Brownell KD (Eds.), Eating disorders and obesity: A Comprehensive Handbook (2nd ed., pp. 467–472). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett S, Burchenal CA, Haber L, Batten K, & Phillips E (2020). Understanding and effectively addressing disparities in obesity: A systematic review of the psychological determinants of emotional eating behaviours among Black women. Obesity Reviews, 21(6), e13010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Himmelstein MS, & Pearl RL (2020). Weight stigma as a psychosocial contributor to obesity. American Psychologist, 75(2), 274–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranzenhofer LM, Hannallah L, Field SE, Shomaker LB, Stephens M, Sbrocco T, Kozlosky M, Reynolds J, Yanovski JA, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2013). Pre-meal affective state and laboratory test meal intake in adolescent girls with loss of control eating. Appetite, 68, 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, & Agras WS (2000). Test- retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28(3), 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL (1999). Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 8(1), 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shank LM, Crosby RD, Grammer AC, Shomaker LB, Vannucci A, Burke NL, Stojek M, Brady SM, Kozlosky M, Reynolds JC, Yanovski JA, & Tanofsky-Kraff M (2017). Examination of the interpersonal model of loss of control eating in the laboratory. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 76, 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Elliott C, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Ranzenhofer LM, Roza CA, Yanovski SZ, & Yanovski JA (2010). Salience of loss of control for pediatric binge episodes: does size really matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(8), 707–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, Crosby RD, Swanson SA, Solmi F, & Field AE (2013). Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: does loss of control matter? JAMA Pediatrics, 167(2), 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD (1973). Manual for the State-trait Anxiety Inventory for Children. Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Little TD, Ilardi SS, Forehand R, Brody GH, & Hunter HL (2006). A confirmatory comparison of the factor structure of the Children’s Depression Inventory between European American and African American youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(6), 773–788. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiensmeier-Pelster J, Schürmann M, & Duda K (2000). Depressions-Inventar für Kinder und Jugendliche:(DIKJ). Hogrefe, Verlag für Psychologie. [Google Scholar]

- Story M, French SA, Resnick MD, & Blum RW (1995). Ethnic/racial and socioeconomic differences in dieting behaviors and body image perceptions in adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 18(2), 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, & Merikangas KR (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 714–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M (2008). Binge eating among children and adolescents. In Jelalian E & Steele R (Eds.), Handbook of childhood and adolescent obesity (pp. 43–59). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, Roza CA, Wolkoff LE, Columbo KM, Raciti G, Zocca JM, Wilfley DE, Yanovski SZ, & Yanovski JA (2011). A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(1), 108–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, Brady SM, Galescu O, Demidowich A, Olsen CH, Kozlosky M, Reynolds JC, & Yanovski JA (2017). Excess weight gain prevention in adolescents: Three-year outcome following a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(3), 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, Ranzenhofer LM, Elliott C, Brady S, Radin RM, Vannucci A, Bryant EJ, Osborn R, Berger SS, Olsen C, Kozlosky M, Reynolds JC, & Yanovski JA (2014). Targeted prevention of excess weight gain and eating disorders in high-risk adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 100(4), 1010–1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, & Yanovski JA (2009). A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(1), 26–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, & Yanovski JA (2004). Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timper K, & Brüning JC (2017). Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 10(6), 679–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian LR, & Porter AM (2016). Weight stigma and eating behavior: A review of the literature. Appetite, 102, 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins B, Frampton I, Lask B, & Bryant- Waugh R (2005). Reliability and validity of the child version of the Eating Disorder Examination: A preliminary investigation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38(2), 183–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]