Abstract

The major purpose of a couple at the first infertility appointment is to get a healthy baby as soon as possible. From diagnosis and decision on which assisted reproduction technique (ART) and controlled ovarian stimulation, to the selection of which embryo to transfer, the dedicated team of physicians and embryologists puts all efforts to shorten the time to pregnancy and live birth. Time seems thus central in assisted reproduction, and we can conveniently use it as a measure of treatment efficiency. How can we measure time to live birth? What timelines do we need to consider to evaluate efficiency? In this paper, we will discuss the importance of “Time” as a fundamental parameter for measuring ART success.

Keywords: Time to live birth, Time to pregnancy, ART, Infertility, MAR

Introduction

An infertile couple when visiting a fertility clinic seeks to have a healthy baby as soon as possible. Most couples, arrive at the clinic already anxious with the time wasted trying to conceive before infertility diagnosis. In the fertility clinic, the couple is then confronted with the variety of specific diagnosis, available treatments in assisted reproduction technique (ART), disparate prices and associated success rates. In some cases, redundant exams prescribed may add to their anxiety level. At this initial stage, would health professionals be able to predict how much time may be necessary to achieve success? Do ART centers currently estimate how much time does it take to obtain a healthy baby accounting for different clinical situations?

In this paper, we will argue “Time” as a relevant parameter to discuss with beneficiaries and to evaluate IVF success. The “Time” parameter seems important not only to those patients who postponed their reproductive projects and know time is running against them, but also to allow patients to better cope with all psychological, economic and social burdens of the ART treatment. In addition, it may also be helpful for health professionals to further differentiate and personalize care.

Success rate evaluation

ART outcomes have initially been evaluated through implantation and pregnancy rates, and later through live birth rates “per transfer” or “per cycle”. However, due to the complexity of the whole treatments, all the cycles relative to a patient, fresh or/and frozen cycles, including failed attempts, should be considered. Such cumulative approach is today considered the most accurate form of evaluation, particularly cumulative live birth rate. Moreover, cumulative evaluation approaches give the patients and the health professionals more relevant information about the chances of a couple to achieve a successful live birth [1–4]. In addition, valuable metrics have been suggested that could help patients and professionals to define IVF success rate, such as sustained implantation rate (SIR). SIR may allow to infer how likely is a particular embryo that will be transferred to give rise to a baby, helping to increase the number of single embryo transfers (eSET) [5].

“Time” is a sensitive outcome measure for overall couple fertility, as fertile couples tend to conceive faster than non-fertile couples [6]. Therefore, in addition to the cumulative live birth rate, ART providers should include in their discussions and assessments the “Time” parameter. Time, together with cumulative live birth rates, will help the clinician, the embryologist, and the patient to better consider and cope with what to expect over a period based on the specific clinical situation and the technical possibilities available. This will additionally help the couple to better manage their expectations, diminishing treatment discontinuation and psychological burden. Since “Time” is a fundamental parameter for the outcome of these treatments, having it included as an additional measure of success will be particularly helpful to manage the patients who postponed their reproductive projects. Furthermore, the increase of the couple’s age, both maternal and paternal, requiring ART treatment will more clearly be appreciated, discussed and considered.

It’s about “Time” to harmonize

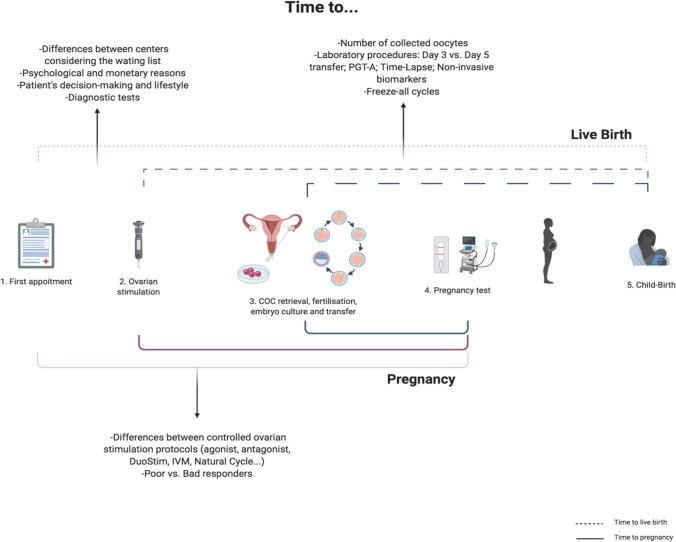

Recently, Sunkara and colleagues [7] brightly discussed “Time” as an outcome measure in fertility-related clinical studies and Duffy et al. [8] proposed time to pregnancy leading to live birth as one of the core outcome parameters to evaluate potential infertility treatments. To accurately assess the “time to” parameter, it is necessary to clearly define which time intervals to consider. In ART treatments, there are multiple possibilities for starting and ending evaluations. Starting points could be: when the couple undergoes the first clinical appointment, the beginning of the medical treatment or assessment, the beginning of the ovarian stimulation or the day of oocyte retrieval (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Time to pregnancy and to live birth: it is possible to have different starting and ending points to measure time in medically assisted reproduction. Among the different options, there are factors that can modify the time to pregnancy or/and to live birth. Image created with BioRender.com

If date of the first clinical appointment is considered as the starting point, as some will defend, then we need to also take into account all the variables that may influence the waiting period. For instance, will a center have a longer time to live birth than another center due to the initial waiting list? Will other reasons, such as economic, additionally contribute for diverse time to live birth? Will a patient or couple previously assessed for their infertility take less time to start treatment than those without such studies? A different interval for each couples’ previous decision-making is an additional variable in such cases.

Considering the ovarian stimulation as a starting point, probably the “time to” parameter will be distinct between different ovary stimulation protocols, although the difference, in most cases, may be diluted in the subsequent duration of procedures. For instance, will agonist or antagonist protocols have different time to live birth? [9, 10]. Will DuoStim (Double Stimulation, with two rounds of ovarian stimulation and two egg retrievals in the same menstrual cycle) or minimal stimulation, with or without in vitro oocyte maturation (IVM), lead to differences from the conventional stimulation ones regarding “time to”? [11, 12]. And how will clinical categories such as a poor/good responder patients impact on time to pregnancy/live birth?

An alternative possibly more neutral and clear starting point is the oocyte retrieval moment. Although it could be criticized by neglecting important preliminary steps of an ART treatment such as the waiting period to consultation or the controlled ovarian stimulation duration, it is perhaps a better option to overpass some of the concerns related to the heterogeneity of the two previously discussed starting points. In addition, there are some clinics that only receive patients for the oocyte retrieval and have reduced previous information.

As an ending point for this assessment, we may have at least three possibilities: until clinical pregnancy, named “time to pregnancy”, until the date of clinical pregnancy that originated child-birth and the day of the child-birth — “time to live birth.” ART professionals are aware of the high percentage of miscarriages involved in this field [3, 4]. Therefore, it is increasingly accepted that the time to clinical pregnancy does not necessarily reflect a successful endpoint treatment. Consequently, the date of the pregnancy that led to a successful child-birth may be a superior endpoint. The child-birth date as an endpoint could even be better considered, since this really complies with the couple outcome wishes — a healthy baby. However, when considering time to live birth, gestational age should be taken into account for correction, since a baby may be born extremely preterm (< 28 weeks), preterm (< 37 weeks) or full term between 37 and 42 weeks. This gestational age discrepancy would result in diverse artefactual times to live birth, where lower values clearly would not reflect better outcomes.

When we specifically consider time to live birth, we should consider months or years as such specific quantification may be the answer the patients are looking for. In addition to clear definitions of the starting and ending points, other variables may be useful considering. For example, we should also incorporate number of oocyte pickups, of mature oocytes obtained, of fertilized oocytes, or of embryos created and of embryo transfer cycles necessary for a live birth, to harmonize the multiple uncontrolled differences between patients (among others, subtle male factor and oocyte quality), laboratory techniques and ART centers.

Discussion and conclusions

Even though it is currently not common to discuss and evaluate the ART success rates through the “Time” parameter, clinicians and embryologists make a daily effort to reduce the patients’ time to live birth. The struggle to select the more appropriate embryo to transfer, making use of highly differentiated technology, is a clear example of such efforts. Which additional parameters in between the mentioned starting and ending points could influence time to live birth?

There are several variables to consider, from the first appointment with a clinician specialist [13], until the choice of the ovarian stimulation protocol. In 2019, a Delphi consensus on time to healthy singleton and decision-making [14] with a thorough discussion on the several steps of ART treatments that could influence time to live birth was published.

The IVF laboratory plays a central role in the success of the treatment. Health professionals are bringing new approaches, although controversially [15], claiming they can reduce the time to live birth. These added factors include PGT-A [16, 17], time-lapse [18], Day 3 vs Day 5 transfer [19, 20] and Artificial Intelligence. All those, as well as some non-invasive biomarkers [21] could theoretically help to reduce time to live-birth by helping with the selection of the most adequate embryo to transfer. Furthermore, we should also consider the patients clinical history, diagnosis, and lifestyle factors, such as obesity [22] and smoking [23]. It is known that advanced maternal and paternal age negatively influence on ART outcomes [24, 25], but how will these factors influence time to live birth? Perhaps the infertility factor (female vs. male), or the specific laboratory fertilization procedure (IVF vs. ICSI) may also influence the Time parameter.

In ART, there is no guarantee of immediate success. It could be helpful for the couples and ART professionals to more specifically calculate the time to achieve their goal of obtaining a healthy baby. By developing a timeline considering both patient and treatment variables, a more accurate calculation of time to live birth may be achieved. “Time” as an evaluation parameter along with cumulative live birth rate will not only lead to more transparent and informative interactions but could also help treatment decisions for both patients and health professionals. Undoubtedly “Time” is here to stay!

Author contribution

MM and CEP drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed through literature search and discussion.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live-birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):236–243. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maheshwari A, McLernon D, Bhattacharya S. Cumulative live birth rate: time for a consensus? Hum Reprod. 2015;263. 10.1093/humrep/dev263. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.U. Department of Health, H. Services, C. for Disease Control, N. Center for Chronic Disease Prevention, and H. Promotion, “2019 Assisted reproductive technology fertility clinic and national summary report.” [Online]. n.d. Available: www.cdc.gov/art/reports. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

- 4.de Geyter C, Calhaz-Jorge C, Kupka MS, Wyns C, Mocunu W, Motrenko T, Scaravelli G, Smeenk J, Vidakovic S, Goossens V. The European IVF.monitoring Consortium (EIM) for European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). ART in Europe, 2015: results generated from European registries by ESHRE. Hum Reprod Open. 2020. 10.1093/hropen/hoz038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Fischer C, Scott TR. Three simple metrics to define in vitro fertilization success rates. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(1):6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.te Velde E, Eijkemans R, Habbema H. Variation in couple fecundity and time to pregnancy, an essential concept in human reproduction. Lancet. 2000;355(9219):1928–1929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunkara SK, Zheng W, D’Hooghe T, Longobardi S, Boivin J. Time as an outcome measure in fertility-related clinical studies: long-awaited. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(8):1732–1739. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy JMN, AlAhwany H, Bhattacharya S, Collura B, Curtis C, Evers JLH, Farquharson RG, Franik S, Giudice LC, Khalaf Y, Knijnenburg JML, Leeners B, Legro RS, Lensen S, Vazquez-Niebla Jc, Mavrelos D, Mol BWJ, Niederberger C, Ng EHY, Otter SD, Puscasiu L, Rautakallio-Hokkanen S, Repping S, Sarris I, Simpson JL, Strandell A, Strawbridge, Torrance HL, Vail A, van Wely M, Vercoe MA, Vuong NL, Wang AY, Wang R, Wilkinson J, Youssef MA, Farquhar CM. Core Outcome Measure for Infertility Trials (COMMIT) initiative. Developing a core outcome set for future infertility research: an international consensus development study. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(12):2725–2734. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deaa241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devroey P, Aboulghar M, Garcia-Velasco J, Griesinger G, Humaidan P, Kolibianakis E, Ledger W, Tomás C, Fauser BCJM. Improving the patient’s experience of IVF/ICSI: a proposal for an ovarian stimulation protocol with GnRH antagonist co-treatment. Hum Reprod. 2008;24(4):764–774. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambalk CB, Banga FR, Huirne JA, Toftager M, Pinborg A, Homburg R, can der Veen F, van Wely M. GnRH antagonist versus long agonist protocols in IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis accounting for patient type. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(5):560–579. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ho VNA, Braam SC, Pham Td, Mol BW, Vuong LN. The effectiveness and safety of in vitro maturation of oocytes versus in vitro fertilization in women with a high antral follicle count. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(6):1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cecchino GN, Roque M, Cerrillo M, Filho RR, Chiamba FS, Hatty JH, García-Velasco JA. DuoStim cycles potentially boost reproductive outcomes in poor prognosis patients. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2021;37(6):519–522. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2020.1822804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boltz MW, Sanders JN, Simonsen SE, Stanford JB. Fertility treatment, use of in vitro fertilization, and time to live birth based on initial provider type. J Am Board Fam. 2017;30(2):230–238. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosch E, Bulletti C, Copperman AB, Fanchin R, Yarali H, Petta CA, Polyzos NP, Shaapiro D, Ubaldi FM, Velasco JAG, Longobardi S, D’Hooghe T, Humaidan P, Delphi TTP Consensus Group How time to healthy singleton delivery could affect decision-making during infertility treatment: a Delphi consensus. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019;38(1):118–130. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper J, Jackson E, Sermon K, Aitken RJ, Harbottle S, Mocanu E, Hardarson T, Mathur R, Viville S, Vail A, Lundin K. Adjuncts in the IVF laboratory: where is the evidence for ‘add-on’ interventions? Hum Reprod. 2017;32(3):485–549. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penzias A, Bendikson K, Butts S, Coutifaris C, Falcone T, Fossum G, Gitlin S, Gracia C, Hansen K, La Barbera A, Mersereau J, Odem R, Paulson R, Pfeifer S, Pisarska M, Rebar R, Reindollar R, Rosen M, Sandlow J, Vernon M, Widra E. Practice Committees of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. The use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A): a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(3):429–436. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacchi L, Albani E, Cesana A, Smeraldi A, Parini V, Fabiani M, Poli M, Capalbo A, Levi-Setti PE. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy improves clinical, gestational, and neonatal outcomes in advanced maternal age patients without compromising cumulative live-birth rate. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(12):2493–2504. doi: 10.1007/s10815-019-01609-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reignier A, Lefebvre T, Loubersac S, Lammers J, Barriere P, Freour T. Time-lapse technology improves total cumulative live birth rate and shortens time to live birth as compared to conventional incubation system in couples undergoing ICSI. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:917–923. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02099-z/Published. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glujovsky D, Farquhar C. Cleavage-stage or blastocyst transfer: what are the benefits and harms? Fertil Steril. 2016;106(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clua E, Rodríguez I, Arroyo G, Racca A, Martínez F, Polyzos NP. Blastocyst versus cleavage embryo transfer improves cumulative live birth rates, time and cost in oocyte recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Reprod Biomed Online. 2022;44(6):995–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrick L, Lee YSL, Gardner DK. Reducing time to pregnancy and facilitating the birth of healthy children through functional analysis of embryo physiology. Biol Reprod. 2019;101(6):1124–1139. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price SA, Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Nankervis AJ, Permezel M, Proietto J. Time to pregnancy after a prepregnancy very-low-energy diet program in women with obesity: substudy of a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanegas JC, Chavarro JE, Williams PL, Ford JB, Toth TL, Hauser R, Gaskins AJ. Discrete survival model analysis of a couple’s smoking pattern and outcomes of assisted reproduction. Fertil Res Pract. 2017;3(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s40738-017-0032-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gleicher N, Kushnir VA, Albertini DF, Barad DH. Improvements in IVF in women of advanced age. J Endocrinol. 2016;230(1):F1–F6. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murugesu S, Kasaven LS, Petrie A, Vaseekaran A, Jones BP, Bracewell-Milnes T, Barcroft JF, Grewal KJ, Getreu N, Galazis N, Sorbi F, Saso S, Ben-Nagi J. Does advanced paternal age affect outcomes following assisted reproductive technology? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2022;45(2):283–331. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2022.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]