Abstract

The presence in nature of species showing drastic differences in lifespan and cancer incidence has recently increased the interest of the scientific community. In particular, the adaptations and the genomic features underlying the evolution of cancer-resistant and long-lived organisms have recently focused on transposable elements (TEs). In this study, we compared the content and dynamics of TE activity in the genomes of four rodent and six bat species exhibiting different lifespans and cancer susceptibility. Mouse, rat, and guinea pig genomes (short-lived and cancer-prone organisms) were compared with that of naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) which is a cancer-resistant organism and the rodent with the longest lifespan. The long-lived bats of the genera Myotis, Rhinolophus, Pteropus and Rousettus were instead compared with Molossus molossus, which is one of the organisms with the shortest lifespan among the order Chiroptera. Despite previous hypotheses stating a substantial tolerance of TEs in bats, we found that long-lived bats and the naked mole rat share a marked decrease of non-LTR retrotransposons (LINEs and SINEs) accumulation in recent evolutionary times.

Subject terms: Cancer, Zoology, Interspersed repetitive sequences, Genetics, Mobile elements

Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) are repetitive mobile elements present in almost all eukaryotes1,2. Many studies have shown that TEs are implicated in gene duplications, inversions, exon shuffling, gene expression regulation and may also play a role in the long-term evolution of eukaryotes3–8. For example, the co-option of TE-related proteins gave rise to vertebrate acquired immune system and mammalian placenta9,10. Although some TE insertions have been co-opted by genomes, the overall TE activity can be disruptive especially at short timescale. Indeed, TEs can be responsible for several human diseases11–13 like immunodeficiency14, coagulation defects15, cardiomyopathies16, and muscular dystrophies17,18. Interestingly, the dysregulation of TEs in somatic cells can lead to the establishment, and development of cancer19–22. The dysregulation of TE activity in cancer cells is so pervasive and accentuated that the methylation level of transposable elements is used as a biomarker for the malignancy of several types of tumours23. Given the manifold effects of TEs on health, it is reasonable to consider TE activity as a key factor able to influence the lifespan of several species24. In this study, we investigate the possible association between TE activity and lifespan by comparing the presence of TEs in genomes of mammals (rodents and bats) with different lifespans and cancer incidences. The TEs that cause mutations and genomic instability in the genomes are the ones currently active and able to move throughout the genome24,25. Since there are no transposition assays available for many organisms, we used the genetic divergence of the TE insertions (see “Methods” section) from their consensus sequences as a proxy for their active or inactive state4. Among all the mammalian species for which genome assemblies are publicly available, we chose four species of Rodentia and six of Chiroptera that: (1) have a high-quality genome assembly based on PacBio or Nanopore or Sanger sequencing data (in order to maximize the quality and quantity of transposable elements assembled1); (2) belong to the same taxonomical order (to maximize their shared evolutionary history); and (3) have comparable body masses. In particular, the inclusion of body mass among the criteria of selection allowed us to work with species that have not evolved biological adaptations to counteract cancer incidence as a function of body size (Peto’s paradox)26. In fact, animals with a large body mass evolved mechanisms to contrast the development of tumours such as the control of the telomerase expression27, or the expansion in copy number of coding genes and miRNAs28,29. Small mammals have a smaller number of cells and generally shorter life cycles30, therefore they are disentangled from the Peto’s paradox. For this reason, we selected mammals with a body mass lower than 2 kg to investigate the relationship between lifespan and TEs avoiding biases related to adaptations to large body masses. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that the genomes of cancer-prone and short-lived species present a higher load of recently inserted TEs compared to cancer-resistant and long-lived species.

Results

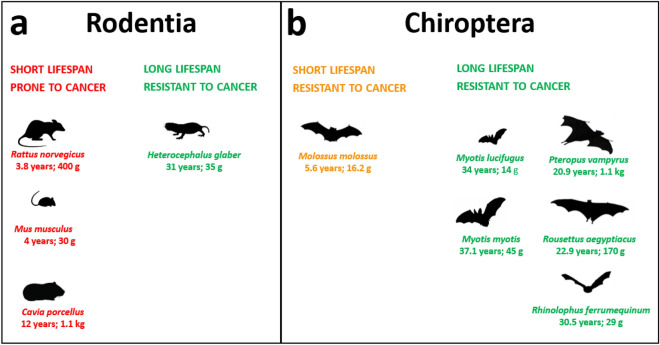

In this study we investigated the possible link between TEs, cancer incidence, and ageing by focusing on the accumulation patterns of TEs in genomes belonging to species showing different lifespans and cancer incidence (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

List of species analysed together with lifespan and body mass information. (a) Rodents with short lifespan and high cancer incidence are indicated in red while species with long lifespan and low cancer incidence are indicated in green. (b) Bats with short lifespan and low cancer incidence are indicated in orange while species with long lifespan and low cancer incidence are indicated in green. This information was retrieved from https://genomics.senescence.info/species/index.html and Speakman et al.31.

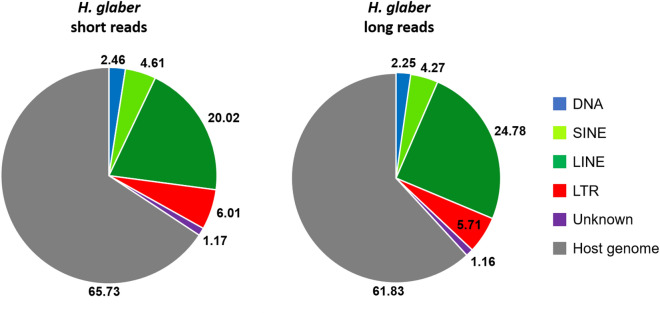

We collected genome assemblies of similar high quality and generated a TE library (Data S1) for the species that previously lacked one to both maximise the presence of TEs in the assemblies and their correct annotation (Tables 1, 2). The de novo TE characterisation highlighted a higher percentage of TEs in the last genome assembly version of H. glaber based on PacBio technology compared to its first version based on short reads (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

The assembly size and the percentage of genome annotated as transposable elements are shown for each rodent genome.

| Species | H. glaber | C. porcellus | M. musculus | R. norvegicus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly size (Gb) | 3.042 | 2.723 | 2.728 | 2.648 |

| Total TE content (%) | 38.16 | 36.01 | 41.86 | 41.76 |

| DNA transposons (%) | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| SINE (%) | 4.3 | 5.5 | 7.6 | 7.2 |

| LINE (%) | 24.78 | 21.4 | 19.2 | 20.9 |

| LTR (%) | 5.7 | 7.4 | 12.6 | 10.7 |

| Unknown (%) | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

Table 2.

The assembly size and the percentage of genome annotated as transposable elements are shown for each bat genome.

| Species | M. myotis | M. lucifugus | R. ferrumequinum | R. aegyptiacus | P. vampyrus | M. molossus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assembly size (Gb) | 2.003 | 2.035 | 2.075 | 1.893 | 1.996 | 2.319 |

| Total TE content (%) | 32.33 | 31.66 | 34.29 | 29.08 | 28.84 | 40.6 |

| DNA transposons (%) | 4.96 | 5.12 | 5.32 | 3.78 | 3.81 | 3.2 |

| Helitrons (%) | 6.93 | 6.18 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.52 |

| SINE (%) | 5.79 | 5.88 | 2.31 | 1.5 | 1.56 | 9.6 |

| LINE (%) | 15.62 | 14.76 | 20.13 | 17.74 | 17.33 | 22.6 |

| LTR (%) | 5.79 | 5.72 | 6.42 | 5.97 | 6.06 | 5.1 |

| Unknown (%) | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.1 |

Figure 2.

Transposable element content comparison between the two genome assemblies of H. glaber. The pie charts show the percentage of the main transposable element categories. The portion of the genome in grey comprises all the repetitive regions not annotated as transposable elements (e.g., tandem repeats and multi-copy gene families) as well as non-repetitive sequences. H. glaber short reads: HetGal_1.0, assembly size 2.6 Gb; H. glaber long reads (PacBio): Heter_glaber.v1.7_hic_pac, assembly size 3 Gb.

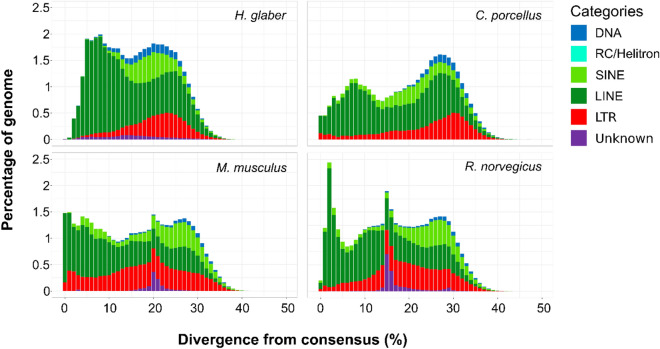

Then, we proceeded to compare the accumulation profiles of TEs between long- (H. glaber) and short-lived rodents (M. musculus, R. norvegicus, C. porcellus) using the output of RepeatMasker (Data S2–S11). We observed a reduced accumulation of transposable elements in the naked mole rat (H. glaber) in recent times with respect to the short-lived rodents (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Transposable element landscapes of rodent species. The X-axis shows the genetic distance between the transposable element insertions and their consensus sequences (Kimura 2-p), whereas the Y-axis shows the percentage of genome annotated as transposable elements.

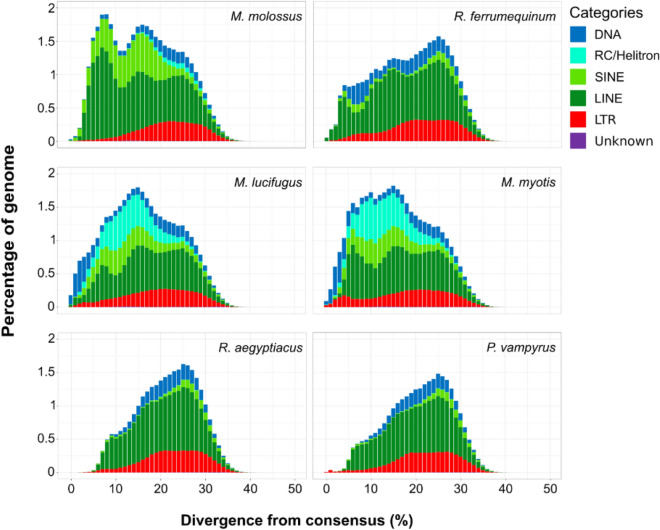

The same analysis was performed in bats. Bat genomes show a high accumulation of class II transposons in all species (Table 2) as well as a drop in the accumulation of non-LTR retrotransposons in recent times (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Transposable element landscapes of bat species. The X-axis shows the genetic distance between the transposable element insertions and their consensus sequences (Kimura 2-p), whereas the Y-axis shows the percentage of the genome annotated as transposable elements.

The genomes of the analysed species are mainly composed of retrotransposons (SINEs, LINEs, LTRs). The main difference between the two orders is that all six bat genomes show a higher percentage of class II transposons (DNA transposons and Helitrons) compared to rodents, with a minimum percentage present in M. molossus (3.72%) and a maximum percentage in M. myotis and M. lucifugus (> 11%; Table 2).

Rodents, in general, show a limited amount of class II transposons with the maximum abundance present in H. glaber (2.3%). The genome of H. glaber has the largest genome size and its percentage of LINE retrotransposons is relatively high compared to the other rodents (Table 1). Among bats, M. myotis and M. lucifugus show a marked accumulation of Helitrons (6.93 and 6.18% respectively) in comparison with the other species that show an abundance of Helitrons below 1%. Notably, the short-lived M. molossus show the largest genome size and the highest percentage of non-LTR retrotransposons (SINEs and LINEs; Table 2). To investigate how the TE content of rodents and bats changed over time and detect the most recently active transposable elements, we used the RepeatMasker annotation (see “Methods” section) to generate a TE “genomic landscape” for each of the species analysed. The TE landscapes are a visualisation of the proportion of repeats in base pairs (Y-axis) at different levels of divergence (X-axis) calculated as a Kimura 2-p distance31 between the insertions annotated and their respective consensus sequences (Figs. 3, 4). The TE landscapes in rodents are mostly dominated by retrotransposons and all of them show an ancestral peak of accumulation between 20 and 30% of divergence (Fig. 3). A small percentage of those ancient TEs is composed of relics of DNA transposons (blue in Fig. 3). The cancer-resistant rodent H. glaber show the highest accumulation of retrotransposons dominated by LINEs (green) between 5 and 10% of divergence followed by a dramatic drop corresponding to the most recent history of this genome (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the three cancer-prone rodents accumulated a large number of retrotransposons in recent times. M. musculus and R. norvegicus share a peak of accumulation between 15 and 20% of divergence, whereas R. norvegicus maintains a stable rate of retrotransposition of SINEs. In comparison to bats, rodents do not present high levels of class II transposons (Tables 1 and 2). The TE landscapes of the six bats (Fig. 4) show a higher intra-order diversity in comparison with the four rodents that are homogenous (Fig. 3). In particular, the two megabats belonging to the Pteropodidae family (Rousettus aegyptiacus and Pteropus vampyrus) presented the lowest TE accumulation (Table 2), whereas R. aegyptiacus, P. vampyrus and R. ferrumequinum have a shared peak of accumulation at 25% of divergence from consensus. The other three species (M. myotis, M. lucifugus and M. molossus), belonging to the clade of Yangochiroptera that evolved around 59 Mya ago32, are more heterogeneous at the level of TE accumulation. In fact, the two species belonging the Myotis genus share their highest peak of accumulation at 15% of divergence, whereas M. molossus has a second more recent taxon-specific peak at 8% of divergence. Despite the two Myotis species having the most similar landscapes (likely due to the closer phylogenetic relationship), M. lucifugus shows a higher accumulation and diversity of TEs in its recent history (0–3% divergence). On the other hand, M. myotis accumulated LTRs with a peak between 4 and 5% of divergence and, in general, the genus Myotis has the most pronounced accumulation of DNA transposons and Helitrons. Finally, we can affirm that in all the bat genomes here considered, the non-LTR retrotransposons (LINEs and SINEs) show a “glaber-like” dynamic with a decrease of accumulation in correspondence of their most recent evolutionary history (Fig. 4). Since we observed that long-lived species of both orders show little accumulation of non-LTR retrotransposons in recent times, we decided to compare in more detail their activity focusing on elements with a divergence lower than 3% (a proxy for recently inserted TEs) and their density of insertion (DI; Fig. 5).

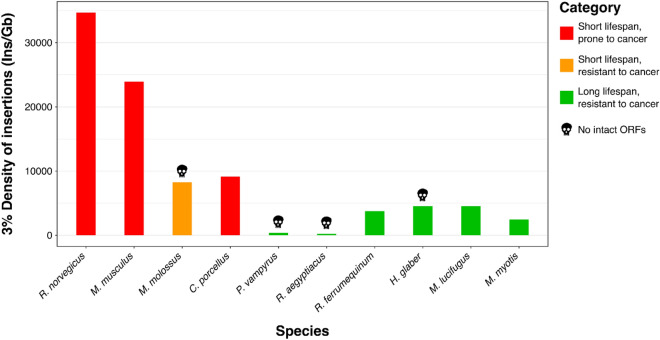

Figure 5.

Density of insertion of recent non-LTR retrotransposons. The X-axis shows the species analyzed in increasing order of longevity. The Y-axis shows the density of recent insertions per Gigabase (< 3% divergence from consensus). Red indicates cancer-prone and short-lived species. Orange indicates cancer-resistant and short-lived species. Green indicates cancer-resistant and long-lived species. The black skull indicates the genomes in which no intact LINE open reading frames (ORFs) were detected.

The density of insertion was calculated as the ratio between the number of non-LTR retrotransposon (SINEs and LINEs) insertions and the assembly size in Gigabase (Fig. 5, Table S1). DI is a parameter used to compare the magnitude of the recent TE accumulation and its potential impact between species with different genome sizes4. When applying this measure in rodents, we found that the H. glaber showed the lowest DI (4,551) compared to the short-lived and cancer-prone species (Fig. 5). Then, we found lower DIs in bats than in rodents (Fig. 5) except for M. molossus (8,269). The lowest DI (< 1000) was observed in R. aegyptiacus and P. vampyrus. The remaining species M. myotis, M. lucifugus and R. ferrumequinum have a DI ranging between 2000 and 5000. In general, the long-lived bats presented a lower DI compared to the short-lived M. molossus (Fig. 5). We also calculated the density of insertion of these retrotransposons per non-overlapping windows (0.5, 1, 1.5 Mb size) across the entire genomes (Figures S1–S3, Table S2). The resulting distribution of TE densities mimic the general DI.

We made a further detailed analysis of LINEs looking for potentially active autonomous non-LTR retrotransposons: we looked for the presence of LINE-related open reading frames (ORFs) with intact protein domains. By doing this, we found that all the analysed rodent genomes present intact LINE ORFs but the genome of H. glaber (Fig. 5). In bats, intact LINE ORFs were found only in M. myotis, M. lucifugus and R. ferrumequinum (Fig. 5). Moreover, we found that M. molossus, R aegyptiacus, and P. vampyrus genome have no intact ORFs. Then, we tested if short- and long-lived species statistically differ in terms of density of insertion. We pooled together the four rodents and six bats to apply the Wilcoxon signed rank paired test. Short-lived species were paired with species showing two-fold longer lifespan for a total of 25 comparisons (see “Methods” section). The test resulted in a p-value of 5.96 × 10–8 (Table S3).

Finally, we explored the possible correlation between the density of young non-LTR retrotransposons and gene, exon, intron, intergenic region densities but no strong correlation was found (Table S4). Similarly, we tested for the correlation between the TE density and gene density in gene-rich and gene-poor regions, but no general pattern was found (Table S5a–b).

Discussion

Transposable element activity and accumulation can have manifold effects on genomes and biological phenotypes. Multiple studies have linked TEs to ageing and the development of several diseases including cancer14,33–36. Here, we have studied the relationship between TEs and two different aspects of mammal life: longevity and cancer incidence. In rodents, the short lifespan is associated with the presence of cancer37. On the other hand, bats are considered cancer-resistant species38 (Fig. 1b). The animals considered in this study are known to have different lifespans while sharing similar, small, body sizes (< 2 kg). H. glaber is the rodent with the longest lifespan known (31 years) and resistant to cancer while the other rodents show shorter lifespans of 12 (C. porcellus), 4 (M. musculus) and 3.8 (R. norvegicus) years. Chiroptera species, as far as it is currently known, are long-lived species and resistant to cancer (only a few confirmed cases have been reported39). Since TEs have been extensively linked to the development of cancer, we investigated the TE content of bats and rodents to see if it is possible to find shared features between long-lived bat and rodent species.

To analyse the TE content of these organisms, we relied on the use of high-quality genome assemblies based on long reads that better represent the actual genomic repetitive content with respect to assemblies based on short reads1. The use of long read-based genome assemblies is particularly important when analysing young TE insertions (as in this study) that are highly homogeneous and tend to be underrepresented in short read assemblies2,40. On top of that, the combination of long read assemblies and custom TE libraries maximises the representation and annotation of the transposable element content as highlighted here for the genome of H. glaber (Fig. 2). The first TE annotation of H. glaber without a custom TE library showed a repetitive content of about 25%41 but the use of a proper TE library increased the content to ~ 34% (Fig. 2). Finally, the use of long reads increased the total content of H. glaber TEs to 38% (Fig. 2, Table 1).

By analysing the TE annotations, we found that the main difference between short- and long-lived species of rodents is represented by a drop in non-LTR retrotransposon accumulation at recent times (0–5% divergence; Fig. 3). Similarly, the long-lived species of bats showed a drop in non-LTR retrotransposon accumulation at recent times (Fig. 4) while presenting an overall accumulation of class II transposons (DNA transposons and Helitrons). Previous studies hypothesised that bats have a higher tolerance for the activity of transposable elements with alternative ways to dampen potential health issues due to this activity38,42. Given our observation on the shared drop of non-LTR retrotransposons accumulation in bats and in H. glaber, we add to the aforementioned hypothesis, that the specific repression of non-LTR retrotransposon activity may enhance cancer resistance. In fact, the non-LTR retrotransposons are the most prevalent types of TEs in rodents (Fig. 3, Table 1) and the most extensively investigated by biomedical research given that they are the only active TEs in the human genome43.

Since the total landscapes of TEs include remote evolutionary dynamics which are unlikely to be associated with the genetics and physiology of cancer and aging, we compared the most recent accumulation of non-LTR retrotransposons between the long-lived and short-lived species considered in this study using the density of recent insertions (0–3% of divergence from consensus). As expected, cancer-prone species present a higher load of recently inserted non-LTR retroelements than cancer-resistant species (Fig. 5). While lifespan of rodents showed a strong relation with the recent activity of non-LTR retrotransposons (Fig. 5), the same type of relation for bats is less clear. However, based on DI comparisons, we noticed that the long-lived bats show a DI similar to the sole long-lived cancer-resistant rodent (H. glaber), while the sole short-lived bat (M. molossus) shows a DI value more similar to short-lived rodents. Finally, by comparing species with large differences in their lifespans, we reject the hypothesis of independency of non-LTR retrotransposons accumulation with ageing in small mammals (Wilcoxon test, p-value: 5.96 × 10–8).

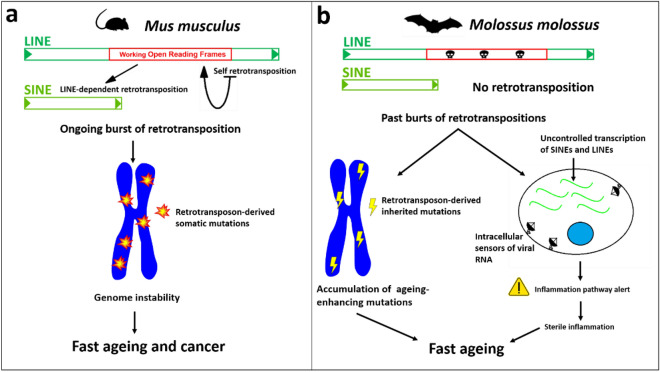

Given the pattern of DI observed in rodents, we speculate that the recent accumulation of non-LTRs may be related to the lifespan of these species (Fig. 1a, 5, 6a). On top of that, we also found that the genome of H. glaber does not contain intact ORFs of LINEs, which is another clue for the absence of currently active non-LTR retrotransposons (Fig. 5). The absence of intact LINE ORFs in the long read genome assembly confirms the same observation previously reported on the short read based genome assembly44. In bats, we observed that M. molossus (shortest lifespan in bats), showed the highest DI, and no intact LINE ORFs (Fig. 5) but has a very high percentage of non-autonomous SINEs compared to long-lived bats (Table 2). SINEs are about 300 bp long and do not present any protein coding sequence, which makes them unable to retrotranspose autonomously: SINEs rely on the exploitation of the retrotransposition machinery provided by LINEs to move throughout the genome (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6.

Hypothetical contribution of non-LTR retrotransposons to the fast ageing of rodents and bats. (a) Mus musculus genome bears active non-LTR retrotransposons that destabilize the genome with continuous events of retrotransposition causing cancer and other diseases that reduce the mouse lifespan. (b) Molossus molossus is both a cancer-resistant and short-lived species. The high density of SINEs derives from a past accumulation of insertions (Fig. 4), that may have resulted in the accumulation of ageing enhancing mutations, and the continuous transcription of these retroelements may trigger cellular inflammation and cause a widespread sterile inflammation. In this scenario, the fitness of M. molossus is not impaired but its lifespan is reduced.

Given that the M. molossus genome lacks intact LINE ORFs, it is reasonable to assume that both LINEs and SINEs are currently inactive in this species (Fig. 6b). This begs the question of why M. molossus has a short lifespan. The density of recently inserted non-LTR elements in M. molossus is 8269 per Gb, which is comparable to the value in Cavia porcellus (9,163 insertions per Gb). In contrast, the long-lived rodent Heterocephalus glaber has a DI of only 4,550 insertions per Gb, while the long-lived Myotis lucifugus has 4,531 insertions per Gb. These findings suggest that future studies on bats should consider two phenomena: first, the potential impact of the accumulation of LINE and SINE insertions on age-related conditions, and second, the cytotoxic effects of an excess of transcribed RNA from these retrotransposons.

A large number of very similar insertions across the chromosomes may cause structural polymorphisms (e.g., through non-allelic homologous recombination events) independently from the retrotransposition itself45. For example, in the recent history of the human genome, LINE1-driven ectopic recombination events caused genomic rearrangements that can be responsible for several diseases46. Moreover, it has been observed in the African killifishes that an accumulation of detrimental polymorphisms following a burst of TEs can undergo phases of relaxed selection were the mutations eventually promote age-associated diseases and reduced lifespan47. Among the killifishes, the turquoise killifish has a lifespan of 4–8 months (likely the shortest lifespan among vertebrates47) but despite the accumulation of mutations that leads to a fast ageing, this species is fully adapted to its ecological niche demonstrating that a rapid ageing is not necessarily linked to reduced fitness (Fig. 6b). In addition, SINEs can also exert physiological effects by being transcribed. For example, in humans, SINEs of the Alu family have been found to be involved in the inflammatory pathway: upon viral infection, the interferon 1 mediates the overexpression of Alu sequences which function as an amplifier of the immune response by stimulating the intracellular viral RNA sensor systems48. Despite the involvement of SINEs in the human immune response, the same upregulation of Alu elements, or the excessive sensitivity of the viral RNA sensors, has been linked to autoimmune diseases49. Furthermore, as non-coding RNAs are emerging as essential components of neuroinflammation, a recent study has included Alu SINEs as possible promoters of neurodegenerative diseases50. More in general, the increased transcription of non-LTR retrotransposons (both LINEs and SINEs) in humans may contribute to so-called “sterile inflammation” (Fig. 6b), a phenomenon for which a chronic state of inflammation is triggered without the presence of any obvious pathogen and that is exacerbated with age (“inflammaging”)51. Therefore, we speculate that the marked accumulation of SINEs in M. molossus might trigger phenomena similar to the sterile inflammation and inflammaging that can cause a shortening of its lifespan. For these reasons M. molossus, together with the well-known H. glaber, may be an exceptional model for biogerontology. Further bioinformatic research can be developed in this respect and may lead to a more precise understanding of the regulation of TEs in the study of longevity and oncology and potential new biomedical applications.

Methods

Samples

In order to avoid biases related to potential underestimations of the TE content, in this study we chose those species of mammals from which high-quality genome assemblies were available. The genome assemblies for the 10 species used were retrieved from NCBI and their accession numbers are: Mus musculus (GCA_000001635.8) [Genome Reference Consortium mouse reference 38], Rattus norvegicus (GCA_000001895.4)52, Cavia porcellus (GCA_000151735.1)53, Heterocephalus glaber (GCA_014060925.1)54, Rousettus aegyptiacus (GCA_014176215.1)55, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (GCA_014108255.1)55, Molossus molossus (GCA_014108415.1)55, Pteropus vampyrus (GCA_000151845.1)53, Myotis myotis (GCA_014108235.1)55, Myotis lucifugus (GCA_000147115.1)53. The species selected belong to Rodentia and Chiroptera orders. Their most recent common ancestor dates back to the Mesozoic era 90 Mya ago56. The large evolutionary distance among these two orders allowed us to find genomic features potentially conserved in all mammals. Body mass is generally positively related to the lifespan30 therefore, in our study, we chose to analyse genomes belonging to small-sized mammals (between 12 g and 1.1 kg). The comparisons were carried out using species belonging to the same taxonomical order to maximize their shared evolutionary history and life history traits. These species were also selected and compared based on their lifespans (Fig. 1). The genome assemblies analysed are all based on Sanger or PacBio technologies and selected to maximize their assembled repetitive content1. The short41 (GCA_000230445.1) and long read-based54 genome assemblies of H. glaber were compared in order to estimate the differences in TE content due to technological biases.

Repetitive element libraries and annotation

To analyze the content of transposable elements in genomes, the genome assemblies must be annotated with proper libraries of TE consensus sequences. A consensus sequence represents the reference sequence of a specific subfamily of transposable elements. The repeat annotation software (e.g., RepeatMasker) uses such libraries of consensus sequences to find instances (or insertions) of each repetitive element within the genome assemblies. From the alignments of the TE insertions found in the genome assembly and their consensus sequences, it is possible to estimate the age of such insertions based on the genetic distance given by the alignments: the higher the distance, the higher the age of the insertions. All the species analysed have a species-specific repeat library already available except for H. glaber. Therefore, we made a de novo repeat library of H. glaber using RepeatModeler2 with the option -LTRstruct57. The resulting consensus sequences were merged with the ancient mammalian TE families (LINE2 and MIR SINEs) downloaded from RepBase (https://www.girinst.org/repbase). All the genome assemblies of rodents (but H. glaber) were masked using RepeatMasker (v. 4.1.0)58 and the Rodentia-specific library (Repbase release 20181026). Similarly, the bat genome assemblies were masked using the Chiroptera-specific library from Repbase merged with the curated TE libraries produced by Jebb et al.55. The RepeatMasker annotations were performed using the options -a -xsmall -gccalc -excln. The annotations were then visualized as “genomic landscapes”: barplots that show in the X-axis the genetic distances from the consensus sequences (calculated as Kimura 2-p distance31) and in Y-axis the percentage of the genome occupied by each TE category (Figs. 3, 4). The barplots were made using the ggplot2 R package. For each species, the genome assembly size and the percentage of each TE categories (Tables 1, 2, Fig. 2) were retrieved from the table files produced by RepeatMasker.

Density of young non-LTR retrotransposons

To evaluate the recent activity of non-LTR retrotransposons (LINEs and SINEs), we selected all the non-LTR retrotransposon hits found by RepeatMasker with a divergence from consensus lower than 3%. The 3% threshold is a proxy for most recently inserted elements3,4. To minimise the overestimation of insertions due to the fragmentation of the repeat annotation, we controlled for fragments belonging to the same insertion as RepeatMasker assign them the same identifier. Then we calculated the density of insertion (DI) for each species as the ratio between the number of recent insertions and the corresponding assembly size expressed in Gigabase:

We expect that the long-lived species are associated with lower DI with respect to lower lived species. To test this hypothesis, we pooled together bats and rodents creating all possible comparisons of long-lived with short-lived species. Each pair of species were chosen as follows: long-lived species lifespan must be at least two-fold longer than the second species’ lifespan; for example: H. glaber (31 years) versus M. molossus (5.6 years). A total of 25 pairs of species were then compared (Table S3). To test this association, we chose Wilcoxon signed rank paired test (one tailed; alpha: 0.05) since the data are not normally distributed.

We also calculated the density of the number of young non-LTR retrotransposon insertions across the genomes in non-overlapping windows of 0.5, 1 and 1.5 Mb, to then calculate the mean density and standard deviation.

Density of young non-LTR retrotransposons and their correlation to genomic features

To understand if the densities of insertions found in these genomes correlate with the density of genes, exons, introns, and intergenic regions, we collected all the gene annotations available for the species of this study. We found available on NCBI the gene annotations for all the genome assemblies except for Heterocephalus glaber, Pteropus vampyrus and Myotis lucifugus. We then calculated the density of these genomic features for non-overlapping windows of 0.5, 1 and 1.5 Mb as the number of features per unit of window size. To test the correlation between the TE density and the other genomic features, we used the Spearman rank correlation test.

In addition, we tested if there was a correlation between the TE density and gene density in gene-rich and gene-poor regions (windows) specifically. We categorized gene-rich and gene-poor windows based on their gene density distribution. The windows showing a gene density value less or equal to the 0.25 percentile of the distribution were categorized as gene poor. The windows with a gene density value greater or equal to the 0.75 percentile of the gene density distribution were categorized as gene rich. The correlation between the TE and gene densities were tested with the Spearman rank correlation test. Finally, we tested if the TE density in gene-rich and gene-poor regions (windows) statistically differed by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Intact ORFs detection

To check the presence of intact LINE retrotransposons (therefore potentially active), we looked for complete open reading frames (ORFs) that encode for the enzymatic machinery used by LINEs to retrotranspose themselves and the non-autonomous SINE elements. In each species the sequences of LINEs were obtained with BEDTools getfasta command59 using the LINE coordinates annotated by RepeatMasker. A fasta file with the LINE sequences for each species was produced and used as input for the R script orfCheker.R (https://github.com/jamesdgalbraith/OrthologueRegions/blob/master/orfChecker.R) to find intact LINE ORFs. The script considers a LINE ORF to be intact if it contains both complete reverse transcriptase and endonuclease domains.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Laura Anderlucci for her help with the statistical analysis. This study has been funded by MAPS Department funds BIRD2021 - prot. BIRD213010, University of Padova.

Author contributions

M.R. and C.T. conceived the study. M.R., V.P., A.B. and C.T. designed and performed the analysis. M.R. and V.P. wrote the first manuscript draft, and all authors edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Data availability

All the genome assemblies used in this study were retrieved from NCBI: Mus musculus: GCA_000001635.8; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_000001635.8/. Rattus norvegicus: GCA_000001895.4; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000001895.5/. Cavia porcellus: GCA_000151735.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000151735.1/. Heterocephalus glaber (based on long reads): GCA_014060925.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_014060925.1/. Heterocephalus glaber (based on short reads): GCA_000230445.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000230445.1/. Rousettus aegyptiacus: GCA_014176215.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014176215.1/. Rhinolophus ferrumequinum: GCA_014108255.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_014108255.1/. Molossus molossus: GCA_014108415.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014108415.1/. Pteropus vampyrus: GCA_000151845.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000151845.1/. Myotis myotis: GCA_014108235.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014108235.1/. Myotis lucifugus: GCA_000147115.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000147115.1/. The code used for the analysis can be found at: https://github.com/marcoricci20/TEanalysis/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-36006-6.

References

- 1.Peona V, Weissensteiner MH, Suh A. How complete are “complete” genome assemblies? An avian perspective. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2018;18:1188–1195. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peona V, et al. Identifying the causes and consequences of assembly gaps using a multiplatform genome assembly of a bird-of-paradise. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021;21:263–286. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jurka J, Bao W, Kojima KK. Families of transposable elements, population structure and the origin of species. Biol. Direct. 2011;6:44. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ricci M, Peona V, Guichard E, Taccioli C, Boattini A. Transposable elements activity is positively related to rate of speciation in mammals. J. Mol. Evol. 2018;86:303–310. doi: 10.1007/s00239-018-9847-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janoušek V, Laukaitis CM, Yanchukov A, Karn RC. The role of retrotransposons in gene family expansions in the human and mouse genomes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:2632–2650. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran JV, DeBerardinis RJ, Kazazian HHJ. Exon shuffling by L1 retrotransposition. Science. 1999;283:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbarbary RA, Lucas BA, Maquat LE. Retrotransposons as regulators of gene expression. Science. 2016;351:aac7247. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunarso G, et al. Transposable elements have rewired the core regulatory network of human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:631–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koonin EV, Krupovic M. Evolution of adaptive immunity from transposable elements combined with innate immune systems. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015;16:184–192. doi: 10.1038/nrg3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch VJ, Leclerc RD, May G, Wagner GP. Transposon-mediated rewiring of gene regulatory networks contributed to the evolution of pregnancy in mammals. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:1154–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kazazian HHJ, Goodier JL. LINE drive retrotransposition and genome instability. Cell. 2002;110:277–280. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00868-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordaux R, Batzer MA. The impact of retrotransposons on human genome evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:691–703. doi: 10.1038/nrg2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Callinan PA, Batzer MA. Retrotransposable elements and human disease. Genome Dyn. 2006;1:104–115. doi: 10.1159/000092503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hancks DC, Kazazian HH., Jr Roles for retrotransposon insertions in human disease. Mob. DNA. 2016;7:9. doi: 10.1186/s13100-016-0065-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beauchamp NJ, Makris M, Preston FE, Peake IR, Daly ME. Major structural defects in the antithrombin gene in four families with type I antithrombin deficiency–partial/complete deletions and rearrangement of the antithrombin gene. Thromb. Haemost. 2000;83:715–721. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1613898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida K, Nakamura A, Yazaki M, Ikeda S, Takeda S. Insertional mutation by transposable element, L1, in the DMD gene results in X-linked dilated cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:1129–1132. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondo-Iida E, et al. Novel mutations and genotype-phenotype relationships in 107 families with Fukuyama-type congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:2303–2309. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.12.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narita N, et al. Insertion of a 5’ truncated L1 element into the 3’ end of exon 44 of the dystrophin gene resulted in skipping of the exon during splicing in a case of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 1993;91:1862–1867. doi: 10.1172/JCI116402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Martin B, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes identifies driver rearrangements promoted by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat. Genet. 2020;52:306–319. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0562-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carreira PE, Richardson SR, Faulkner GJ. L1 retrotransposons, cancer stem cells and oncogenesis. FEBS J. 2014;281:63–73. doi: 10.1111/febs.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helman E, et al. Somatic retrotransposition in human cancer revealed by whole-genome and exome sequencing. Genome Res. 2014;24:1053–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.163659.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tubio JMC, et al. Extensive transduction of nonrepetitive DNA mediated by L1 retrotransposition in cancer genomes. Science. 2014;345:1251343. doi: 10.1126/science.1251343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hur K, et al. Hypomethylation of long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1) leads to activation of protooncogenes in human colorectal cancer metastasis. Gut. 2014;63:635–646. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peona V, et al. The avian W chromosome is a refugium for endogenous retroviruses with likely effects on female-biased mutational load and genetic incompatibilities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021;376:186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Zheng X, Xiao D, Zheng Y. Age-associated de-repression of retrotransposons in the Drosophila fat body, its potential cause and consequence. Aging Cell. 2016;15:542–552. doi: 10.1111/acel.12465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peto R. Epidemiology, multistage models, and short-term mutagenicity tests. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016;45:621–637. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorbunova V, Seluanov A. Coevolution of telomerase activity and body mass in mammals: From mice to beavers. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009;130:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sulak M, et al. TP53 copy number expansion is associated with the evolution of increased body size and an enhanced DNA damage response in elephants. Elife. 2016;5:1–30. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vischioni C, et al. miRNAs copy number variations repertoire as hallmark indicator of cancer species predisposition. Genes (Basel) 2022;13:1046. doi: 10.3390/genes13061046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speakman JR. Body size, energy metabolism and lifespan. J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208:1717–1730. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kimura M. Journal of Molecular Evolution: Introduction. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agnarsson I, Zambrana-Torrelio CM, Flores-Saldana NP, May-Collado LJ. A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (chiroptera, mammalia) PLoS Curr. 2011 doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morales-Hernández A, et al. Alu retrotransposons promote differentiation of human carcinoma cells through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:4665–4683. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen THM, et al. L1 retrotransposon heterogeneity in ovarian tumor cell evolution. Cell Rep. 2018;23:3730–3740. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burns KH. Transposable elements in cancer. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2017;17:415–424. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell PJ, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Albuquerque TAF, Drummond do Val L, Doherty A, de Magalhães JP. From humans to hydra: patterns of cancer across the tree of life. Biol. Rev. 2018;93:1715–1734. doi: 10.1111/brv.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorbunova V, Seluanov A, Kennedy BK. The world goes bats: Living longer and tolerating viruses. Cell Metab. 2020;32:31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bradford C, Jennings R, Ramos-Vara J. Gastrointestinal leiomyosarcoma in an Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010;22:462–465. doi: 10.1177/104063871002200324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peona V, Kutschera VE, Blom MPK, Irestedt M, Suh A. Satellite DNA evolution in Corvoidea inferred from short and long reads. Mol. Ecol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/mec.16484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim EB, et al. Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature. 2011;479:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorbunova V, et al. The role of retrotransposable elements in ageing and age-associated diseases. Nature. 2021;596:43–53. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03542-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guichard E, et al. Impact of non-LTR retrotransposons in the differentiation and evolution of anatomically modern humans. Mob. DNA. 2018;9:28. doi: 10.1186/s13100-018-0133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivancevic AM, Kortschak RD, Bertozzi T, Adelson DL. LINEs between species: Evolutionary dynamics of LINE-1 retrotransposons across the eukaryotic tree of life. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:3301–3322. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Berdan EL, et al. Unboxing mutations: Connecting mutation types with evolutionary consequences. Mol. Ecol. 2021;30:2710–2723. doi: 10.1111/mec.15936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J, Han K, Meyer TJ, Kim H-S, Batzer MA. Chromosomal inversions between human and chimpanzee lineages caused by retrotransposons. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e4047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cui R, et al. Relaxed selection limits lifespan by increasing mutation load. Cell. 2019;178:385–399.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hung T, et al. The Ro60 autoantigen binds endogenous retroelements and regulates inflammatory gene expression. Science. 2015;350:455–459. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Volkman HE, Stetson DB. The enemy within: Endogenous retroelements and autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:415–422. doi: 10.1038/ni.2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polesskaya O, et al. The role of Alu-derived RNAs in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative conditions. Med. Hypotheses. 2018;115:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14:576–590. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gibbs RA, et al. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature. 2004;428:493–521. doi: 10.1038/nature02426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindblad-Toh K, et al. A high-resolution map of human evolutionary constraint using 29 mammals. Nature. 2011;478:476–482. doi: 10.1038/nature10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou X, et al. Beaver and naked mole rat genomes reveal common paths to longevity. Cell Rep. 2020;32:107949. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jebb D, et al. Six reference-quality genomes reveal evolution of bat adaptations. Nature. 2020;583:578–584. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2486-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meredith RW, et al. Impacts of the cretaceous terrestrial revolution and KPg extinction on mammal diversification. Science. 2011;334:521–524. doi: 10.1126/science.1211028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flynn JM, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:9451–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921046117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0 (2015).

- 59.Quinlan AR. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014;2014:11.12.1–11.12.34. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the genome assemblies used in this study were retrieved from NCBI: Mus musculus: GCA_000001635.8; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_000001635.8/. Rattus norvegicus: GCA_000001895.4; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000001895.5/. Cavia porcellus: GCA_000151735.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000151735.1/. Heterocephalus glaber (based on long reads): GCA_014060925.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_014060925.1/. Heterocephalus glaber (based on short reads): GCA_000230445.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000230445.1/. Rousettus aegyptiacus: GCA_014176215.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014176215.1/. Rhinolophus ferrumequinum: GCA_014108255.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCA_014108255.1/. Molossus molossus: GCA_014108415.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014108415.1/. Pteropus vampyrus: GCA_000151845.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000151845.1/. Myotis myotis: GCA_014108235.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_014108235.1/. Myotis lucifugus: GCA_000147115.1; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/data-hub/genome/GCF_000147115.1/. The code used for the analysis can be found at: https://github.com/marcoricci20/TEanalysis/.