Abstract

Gars and bichirs develop scales and teeth with ancient actinopterygian characteristics. Their scale surface and tooth collar are covered with enamel, also known as ganoin, whereas the tooth cap is equipped with an enamel-like tissue, acrodin. Here, we investigated the formation and mineralization of the ganoin and acrodin matrices in spotted gar, and the evolution of the scpp5, ameloblastin (ambn), and enamelin (enam) genes, which encode matrix proteins of ganoin. Results suggest that, in bichirs and gars, all these genes retain structural characteristics of their orthologs in stem actinopterygians, presumably reflecting the presence of ganoin on scales and teeth. During scale formation, Scpp5 and Enam were initially found in the incipient ganoin matrix and the underlying collagen matrix, whereas Ambn was detected mostly in a surface region of the well-developed ganoin matrix. Although collagen is the principal acrodin matrix protein, Scpp5 was detected within the matrix. Similarities in timings of mineralization and the secretion of Scpp5 suggest that acrodin evolved by the loss of matrix secretory stage of ganoin formation: dentin formation is immediately followed by the maturation stage. The late onset of Ambn secretion during ganoin formation implies that Ambn is not essential for mineral ribbon formation, the hallmark of the enamel matrix. Furthermore, Scpp5 resembles amelogenin that is not important for the initial formation of mineral ribbons in mammals. It is thus likely that the evolution of ENAM was vital to the origin of the unique mineralization process of the enamel matrix.

Keywords: ameloblastin, enamelin, ganoid scales, mineral ribbons, SCPP5, SCPP genes

1. INTRODUCTION

The surface of teeth and scales is protected by hypermineralized tissues in various vertebrates. Among these tissues is mammalian dental enamel that forms in a matrix principally composed of three highly specialized proteins, amelogenin (AMEL), ameloblastin (AMBN), and enamelin (ENAM) (Fincham et al., 1999; Moradian-Oldak, 2012; Simmer et al., 2021). Genes encoding these proteins arose by duplication from a common ancestor and are part of the secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein (SCPP) gene family (Kawasaki and Weiss, 2003), which was established in bony vertebrates (Venkatesh et al., 2014; Leurs et al., 2022). The dental enamel matrix is secreted by epithelial cells (ameloblasts) onto the dentin matrix and increases in thickness as ameloblasts retreat from the surface of dentin (Nanci, 2017). During this process, numerous mineral ribbons extend from the junction with dentin to the distal membrane of ameloblasts. Enamel is thus distinct from bone and dentin that require a preassembled collagen-rich matrix for mineralization (Nanci and Warshawsky, 1984; Fincham et al., 1999). When the enamel matrix reaches the full thickness, its organic components are removed from the matrix, and mineral ribbons accelerate the growth in width and thickness (Simmer and Fincham, 1995). As a result, enamel matures into a hypermineralized tissue.

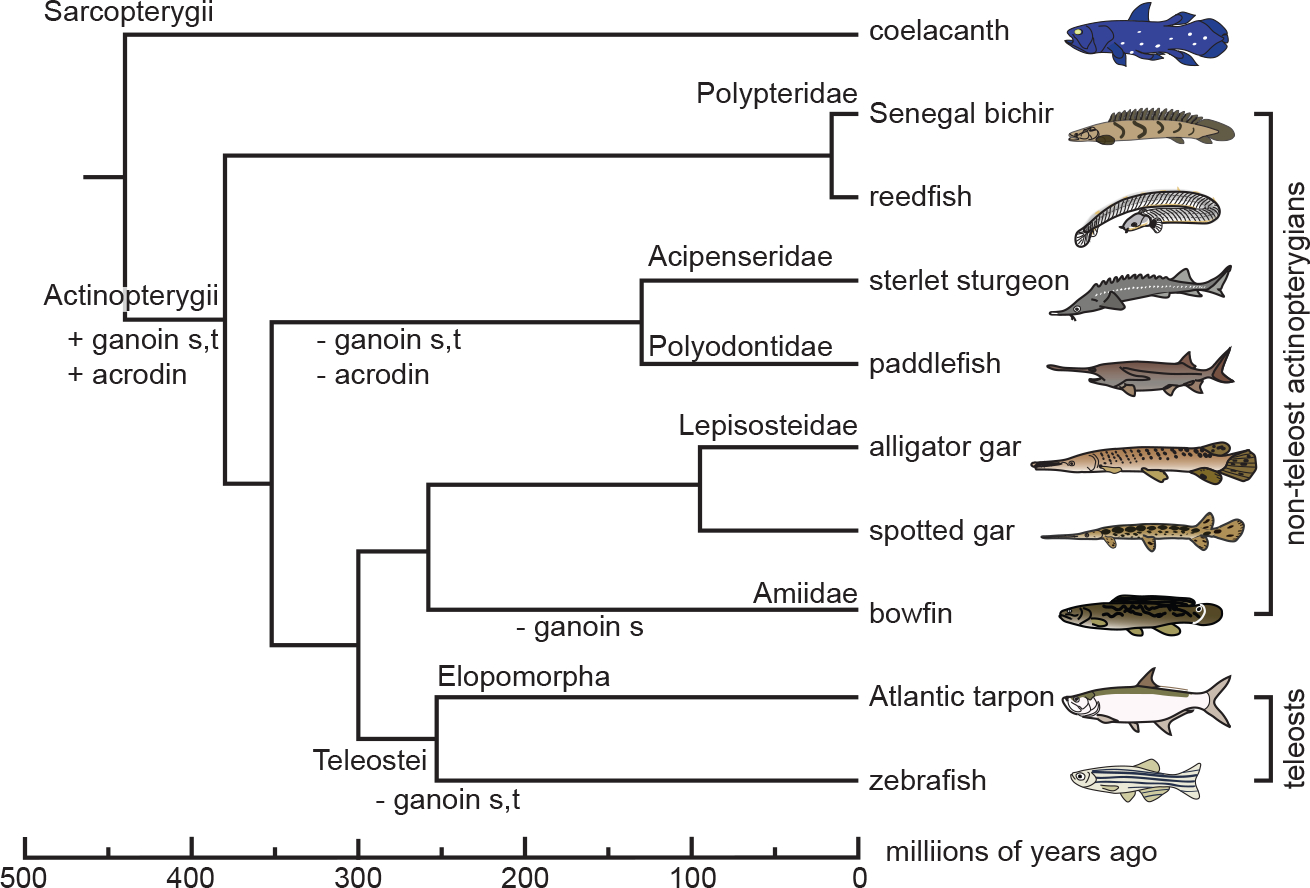

Ganoin originated from an ancient enamel and is present on ganoid scales that arose in stem actinopterygians (Actinopterygii; Figure 1) (Schultze, 2016; Kawasaki et al., 2021). Among extant taxa, however, the ganoid scale is retained only in bichirs (Polypteridae) and gars (Lepisosteidae) (Richter and Smith, 1995; Sire et al., 2009). During ganoin formation, inner ganoin epithelial (IGE) cells express both ambn and enam in spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), like enamel formation in sarcopterygians (Kawasaki et al., 2021). Whereas AMEL encodes the most abundant enamel matrix protein in mammals, its ortholog is not found in spotted gar or other actinopterygians (Qu et al., 2015; Braasch et al., 2016; Kawasaki et al., 2017; Mikami et al., 2022). Instead, a different SCPP gene, scpp5 is highly expressed in IGE cells (Kawasaki et al., 2021; Mikami et al., 2022). Notably, scpp5 of spotted gar and Senegal bichir resembles AMEL of sarcopterygians in the encoding modular structure: the N-terminal aromatic residues-rich region, the Pro- and Gln-rich core region that contains uninterrupted Pro-Xaa-Yaa repeats (Xaa and Yaa represent any amino acids; PXY repeats), and the hydrophilic C-terminus (Toyosawa et al., 1998; Fincham et al., 1999). These findings allowed us to hypothesize that bichir and gar scpp5 genes and sarcopterygian AMEL genes have some overlapping function (Kawasaki et al., 2021).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of Senegal bichir (Polypterus senegalus), reedfish (Erpetoichthys calabaricus), sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), paddlefish (Polyodon spathula), alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula), spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus), bowfin (Amia calva), Atlantic tarpon (Megalops atlanticus), and zebrafish (Danio rerio) among actinopterygians (Actinopterygii). Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae, Sarcopterygii) is also shown. Non-teleost actinopterygians comprise five families, Polypteridae, Acipenseridae, Polyodontidae, Lepisosteidae, and Amiidae. Elopomorpha is the basal group of teleosts (Teleostei) (Near et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2018). The divergence times shown at the bottom are based on a previous study (Hughes et al., 2018). The gain (+) and loss (−) of ganoin in scales (s) and teeth (t) and acrodin (Mikami et al., 2022), indicated along branches, are not in scale.

In bichirs and gars, the tooth surface is covered with two different hypermineralized tissues. The hypermineralized tissue surrounding the tooth collar is enamel because its organic matrix lacks collagen and is secreted exclusively by inner dental epithelial (IDE) cells (Ishiyama et al., 1999; Sasagawa et al., 2008; Sasagawa et al., 2012; Sasagawa et al., 2013). By contrast, the hypermineralized tissue composing their tooth cap (acrodin) is not enamel but enameloid, because its organic matrix is principally composed of collagen that is secreted mostly or exclusively by mesenchymal cell-derived odontoblasts (Ishiyama et al., 2001; Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2005a; Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2005b). In spotted gar, scpp5, ambn, and enam are expressed in IDE cells during the formation of acrodin and collar enamel (Kawasaki et al., 2021). Because the gene expression pattern is common to scale ganoin, collar enamel is referred to below as collar ganoin. We previously hypothesized that both collar ganoin and acrodin are derived from scale ganoin in stem actinopterygians (Figure 1) (Kawasaki et al., 2021). Subsequently, in teleosts, collar ganoin was replaced with collar enameloid.

SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM evolve rapidly, especially in teleosts (Kawasaki et al., 2021). As a result, many teleost AMBN and ENAM orthologs have been annotated incorrectly in the public database. In the present study, we examined structural characteristics of scpp5, ambn, and enam in various actinopterygians, including Atlantic tarpon (Megalops atlanticus, Elopomorpha; a phylogenetically basal teleost; Figure 1) (Near et al., 2012; Hughes et al., 2018), to reveal the evolution of these genes. We also raised antibodies against spotted gar Scpp5, Ambn, and Enam and investigated their secretion during ganoin and acrodin formation to explore similarities and differences among hypermineralized tissues.

2. RESULTS

2.1. SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM in actinopterygians

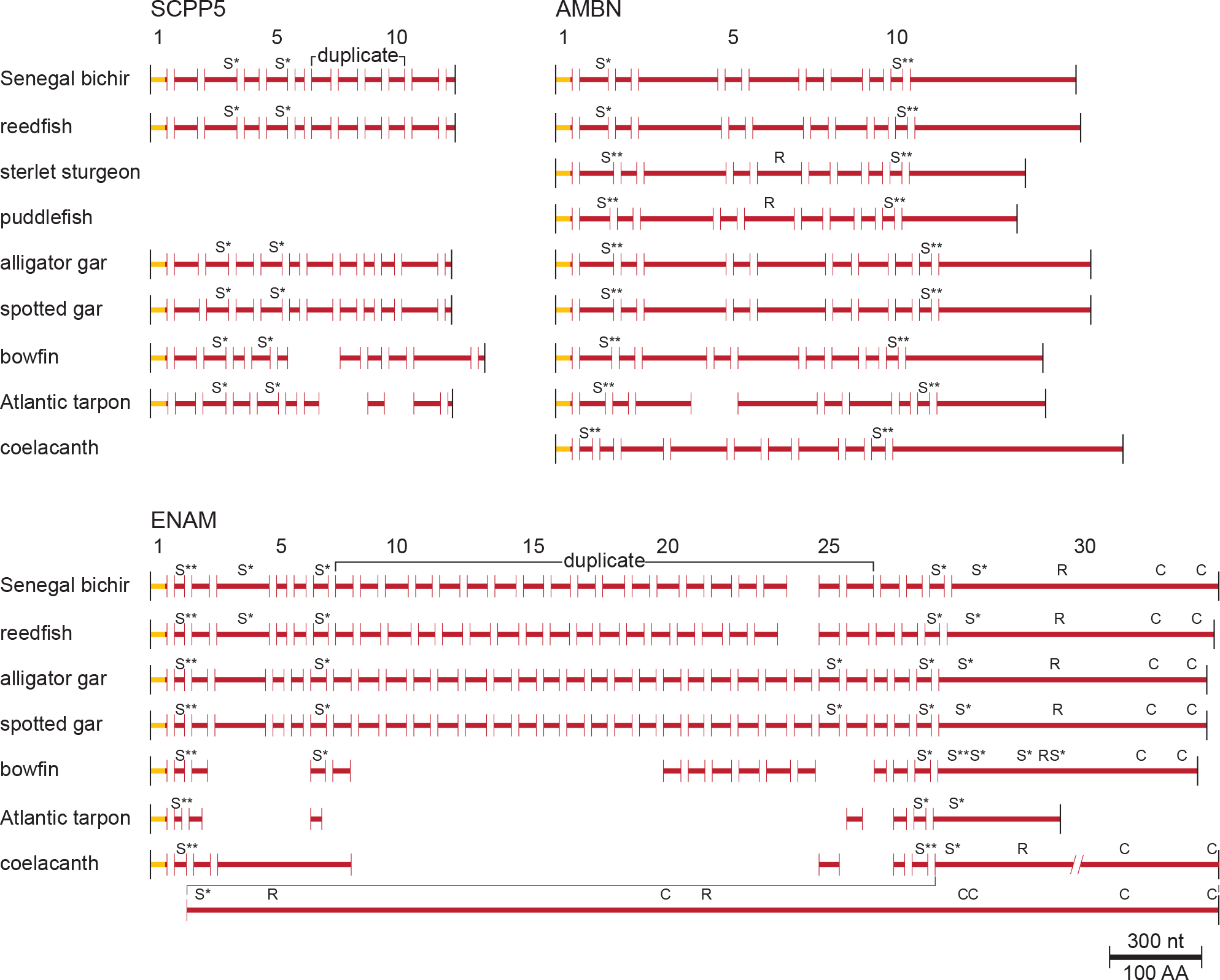

Although scpp5 is found widely in actinopterygians, this gene is absent in sterlet sturgeon and paddlefish (Cheng et al., 2021) presumably in association with their loss of ganoin and acrodin (Mikami et al., 2022). In Senegal bichir and spotted gar, scpp5 encodes three structural modules, common to AMEL of sarcopterygians (Kawasaki et al., 2021). All these three modules are also encoded by scpp5 of reedfish, alligator gar, and bowfin (Figure S1A1). By contrast, neither PXY-repeats nor the hydrophilic C-terminus is encoded by scpp5 of Atlantic tarpon or other teleosts we investigated (Figure S1A2). In bichirs (Senegal bichir and reedfish) and gars (alligator gar and spotted gar), Scpp5 is encoded by 12 exons. Among them, exon 7 – exon 10 encode similar amino acid sequences, implying duplication of these exons (Figures 2 and S1A1). One of these exons is absent from bowfin scpp5, while two of these exons are missing in scpp5 of teleosts we studied. In all scpp5 genes examined so far, protein-coding exon (pc-exon) 3 and pc-exon 5 encode a potentially phosphorylated Ser residue (a pSer residue; S* in Figure 2). Structural characteristics of scpp5 were thus established in stem actinopterygians and are highly conserved in bichirs and gars.

Figure 2.

Protein-coding exons of SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM. The black vertical bars at the beginning and the end of the entire protein-coding exons represent the initiation and termination codons, respectively. The horizontal bars represent the coding regions of the signal peptide (yellow) and the mature protein (red). Each exon is delimited by red vertical bars (splice sites). The number of protein-coding exons for Senegal bichir scpp5, ambn, and enam are indicated on the top. The Ser residue in Ser-Xaa-Glu and Ser-Xaa-pSer (phospho-Ser) is potentially phosphorylated (Tagliabracci et al., 2012; Worby et al., 2021) and is shown by “S*” (“S**” for clustered pSer residues). An integrin-binding sequence (Arg-Gly-Asp) is indicated by “R.” Cys (“C”) residues are not common in most SCPPs but common to ENAM proteins (Kawasaki et al., 2011; Kawasaki and Amemiya, 2014). See the text for “duplicate” exons. The large last protein-coding exon of coelacanth ENAM is shown in the next line. A scale (300 nucleotides (nt)/100 amino acids (AA)) is shown at the bottom. See Figure S1 for encoded amino acid sequences.

In all non-teleost actinopterygians we studied, Ambn is encoded by 11 exons, of which both pc-exon 2 and pc-exon 10 encode one or more pSer residues (Figure 2). Apparently, all these exons are conserved in ambn of coelacanth. In sterlet sturgeon and paddlefish, however, ambn is truncated (Figure S1B1) (Mikami et al., 2022). Among teleosts, one of these 11 exons was not found in Atlantic tarpon (Figure 2), whereas 4 or more exons were unidentified in other teleosts (Figure S1B2). These findings suggest that structural characteristics of AMBN were established in stem osteichthyans and are highly conserved in bichirs, gars, and bowfin among actinopterygians.

Like scpp5, enam was secondarily lost presumably in the common ancestor of sturgeons and paddlefish (Mikami et al., 2022). Enam is encoded by 30 exons in bichirs and 32 exons in gars (Figure 2), the largest number of exons found in SCPP genes. Among these exons, 19 exons in bichirs and 21 exons in gars encode similar amino acid sequences (Figure S1C1), implying duplication of these exons (Figure 2). The absence of similar duplicate exons in sarcopterygians suggests that the extensive exon duplication occurred in stem actinopterygians. Seven of these duplicate exons were found in bowfin (Figure 2), whereas only one or none of these duplicate exons was identified in various teleosts (Figure S1C2). In sarcopterygians, the last pc-exon of ENAM is extremely large among pc-exons of SCPP genes (Figure 2) (Kawasaki and Amemiya, 2014; Kawasaki et al., 2021). By contrast, the last pc-exon of enam is significantly small in teleosts (Figure S1C2). In all ENAM genes studied to date, one or more pSer residues are encoded by pc-exon 2, the penultimate pc-exon, and an upstream region of the last pc-exon. In addition, two or more Cys residues, and one or two integrin-binding Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequences are encoded by the last pc-exon (RGD is not encoded in some mammals) (Al-Hashimi et al., 2010; Kawasaki and Amemiya, 2014). In bichirs and gars, enam also encodes pSer residues in two other exons, and in bowfin, enam encodes more pSer residues in the last pc-exon. By contrast, neither Cys residues nor RGD sequences are encoded by enam in most teleosts (Figures 2 and S1C2). These findings suggest that structural characteristics of ENAM arose in stem osteichthyans and were modified differently in stem actinopterygians and stem sarcopterygians. The structure of enam modified in stem actinopterygians is highly conserved in bichirs and gars, considerably modified in bowfin, and dramatically changed in teleosts.

2.2. Light microscopy (LM) analysis of Scpp5, Ambn, and Enam in the acrodin and ganoin matrices

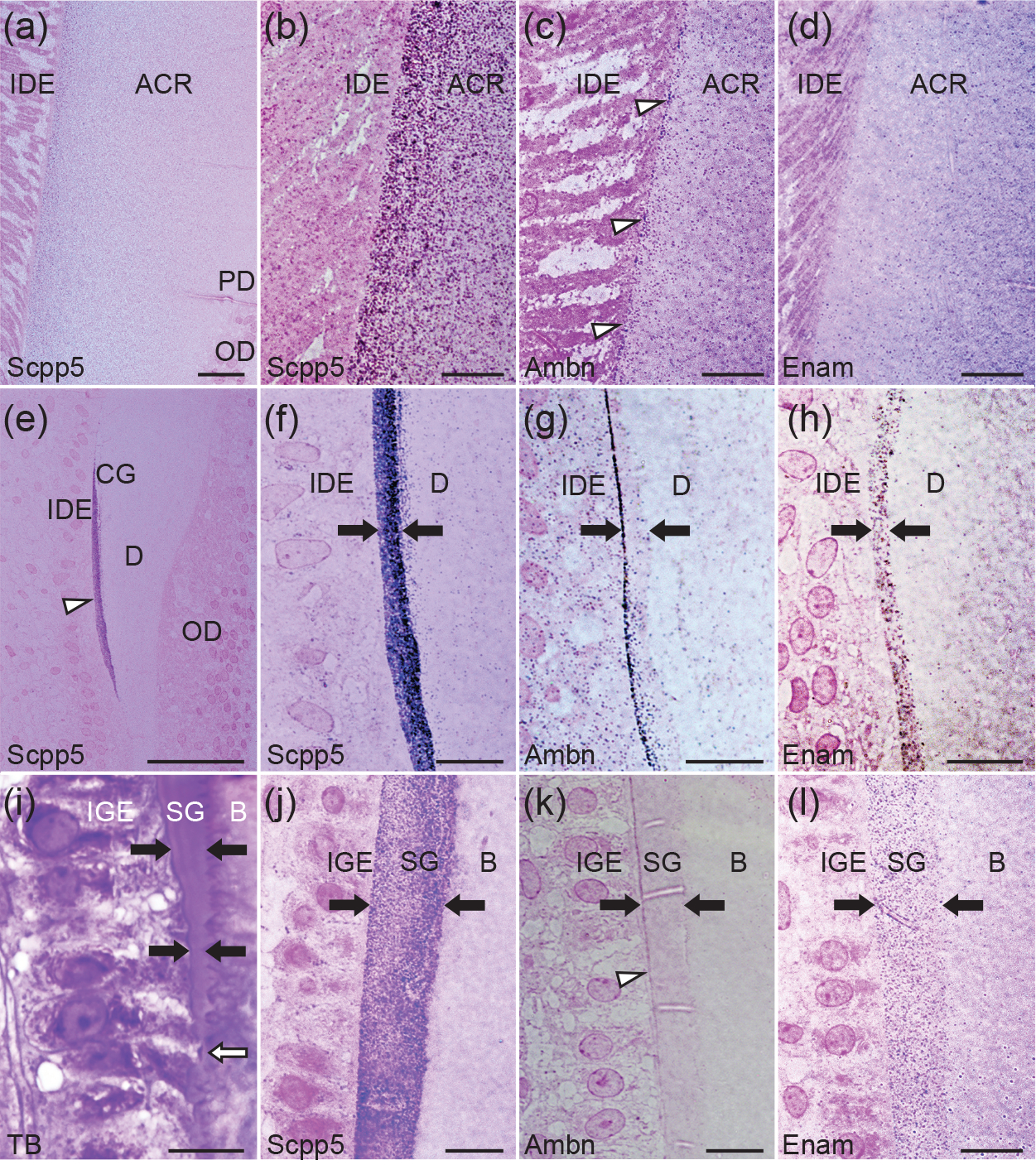

During tooth development in spotted gar, acrodin is the first mineralized tissue that appears between IDE cells and odontoblasts (Sasagawa et al., 2019). Dentin forms next, growing away from acrodin, and then collar ganoin develops on the surface of dentin. The formation of acrodin progresses through matrix formation, mineralization, and maturation (Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2005a; Sasagawa et al., 2019). Using LM, reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was initially detected within the acrodin matrix in the mineralization stage after the body of matrix was formed. The reactivity was relatively high near the surface, gradually decreased toward the dentin-acrodin junction, and not significant in predentin (Figure 3a, b). In the mineralization stage, reactivity with the anti-AMBN and anti-ENAM antibodies was also detected in the acrodin matrix (Figure 3c, d). The most intense reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody was found along the surface close to IDE cells. Negative controls are provided in supporting information (Figure S2A, B).

Figure 3.

Light micrographs showing acrodin (a-d), collar ganoin (e-h), and scale ganoin (i-l) formation in spotted gar. For immunohistochemical analysis (a-h and j-l; a and e, overview), reactivity (protein A-gold particles) is detected as purple or magenta dots. (a-d) The middle stage of acrodin mineralization was analyzed using the anti-SCPP5N (a and b), anti-AMBN (c), and anti-ENAM (d) antibodies. (c) Immunoreactivity along the acrodin surface is shown by open arrow heads. (e-h) The secretory stage of collar ganoin was analyzed using the anti-SCPP5N (e and f), anti-AMBN (g), and anti-ENAM (h) antibodies. (e) Immunoreactivity throughout the collar ganoin layer is indicated by an open arrowhead. (f-l) A pair of closed arrows show the thickness of ganoin. (i-l) The secretory stage of scale ganoin formation was analyzed by staining with toluidine blue (i; TB) and by immunohistochemistry using the anti-SCPP5N (j), anti-AMBN (k), and anti-ENAM (l) antibodies. (i) Newly differentiated IGE cells begin to secrete the ganoin matrix (open arrow). The ganoin layer is thick underneath well-differentiated IGE cells (top). (k) Note increasing reactivity above and below the open arrowhead. Negative controls are provided in Figure S2 (A and B). Scale bars: 20 μm (a), 10 μm (b-d and f-l), 50 μm (e). Abbreviations: acrodin (ACR), bone (B), collar ganoin (CG), dentin (D), inner dental epithelial cells (IDE), inner scale ganoin epithelial cells (IGE), odontoblasts (OD), predentin (PD), scale ganoin (SG).

While the acrodin matrix undergoes maturation, IDE cells begin to secrete the collar ganoin matrix (Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2005a; Sasagawa et al., 2019). In the secretory stage of collar ganoin formation, the anti-SCPP5N antibody showed marked reactivity across the entire thickness of the collar ganoin matrix (Figure 3e, f). In addition, lower reactivity was detected in the dentin matrix near the border with the collar ganoin matrix (Figure 3f). For the anti-AMBN antibody, reactivity was intense only in a superficial region of the collar ganoin matrix close to IDE cells (Figure 3g). Lower reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody was additionally found in IDE cells. Using the anti-ENAM antibody, uniform reactivity was detected in the collar ganoin matrix (Figure 3h).

In gars, scale ganoin forms on a basal bone plate (Sire et al., 2009). As IGE cells differentiate posteroanteriorly (top to bottom in Figure 3i–l), IGE cells elongate and begin to secrete the ganoin matrix on the bone matrix (thick matrix on top in Figure 3i) (Sire, 1994; Sasagawa et al., 2016). During ganoin matrix secretion, striking reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected throughout the matrix (Figure 3j). In addition, lower reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was found in IGE cells and in the bone matrix immediately adjacent to the ganoin matrix. The anti-AMBN antibody exhibited significant reaction along the surface of the ganoin matrix only in a posterior region of the scale (top in Figure 3k). Lower immunoreactivity was additionally found within IGE cells. Reactivity with the anti-ENAM antibody was detected throughout the ganoin matrix (Figure 3l).

2.3. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of acrodin matrix formation

We subsequently used TEM. During acrodin formation, significant reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected only in the middle mineralization stage after packed collagen fibrils fully formed the body of the matrix and after many electron-dense fibrous structures (EDFSs) developed (Figures 4a, b, and S2C) (Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2003). Protein A-gold (PAG) particles (immunoreactivity) were found mostly on collagen fibrils but not on EDFSs (Figure 4a, b). In IDE cells, small round granules in the distal cytoplasm also showed reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody (Figure 4c). In the late mineralization stage, when fine slender crystallites appear in the acrodin matrix (Figure S2D), no significant reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Transmission electron micrographs showing acrodin (a-h) and collar ganoin (i-l) formation in spotted gar. For immunohistochemical analysis (a-e and g-l), PAG particles are detected as dots. The middle (a-c) and late (d) mineralization stages of acrodin formation were analyzed using the anti-SCPP5N antibody. (a) The arrow indicates electron-dense fibrous structures (EDFSs). (b) Packed collagen fibrils are formed. (c) Immunoreactivity in granules of IDE cells is indicated by the open arrow. (d) No significant reactivity was detected. The middle (e) and late (g) mineralization stages of acrodin formation were analyzed using the anti-AMBN. PAG particles along the surface region of acrodin (e and g) and in a granule of IDE cells (e) are indicated by open arrowheads. (f) In the late mineralization stage, crystallites (arrow) are found along the surface region of acrodin (f and g, sequential sections). (h) No significant reaction was detected using the anti-ENAM antibody in the middle mineralization stage of acrodin formation. The secretory stage of collar ganoin formation was analyzed using the anti-SCPP5N (i and j; i, collar ganoin and IDE cells; j, collar ganoin and dentin), anti-AMBN (k), and anti-ENAM (l) antibodies. (i) The open arrowhead indicates PAG particles in a granule of IDE cells. (l) Note that collagen fibrils on the right bottom run parallel to the IDE cell surface. Negative controls are shown in Figure S2 (E–H). Sections were stained with TI-Pb (a and c), TI-Pb-PTA (b, d, e and g-l), or Pb (f). Scale bars: 500 nm (a-e, h, and j), 200 nm (f, g, i, k, and l). See the legend of Figure 3 for abbreviations.

In the middle stage of acrodin mineralization, reactivity with anti-AMBN antibody was detected mostly in a narrow surface region of the acrodin matrix immediately beneath IDE cells (Figure 4e; ~58% of PAG particles were found <100 nm from the IDE cell surface). In addition, reactivity was detected in granules of IDE cells (Figure 4e). In the late mineralization stage, fine crystallites were found in a narrow surface region of the acrodin matrix (Figure 4f). These fine crystallites subsequently fused with more massive slender crystallites that grew from the junction with dentin (Sasagawa et al., 2019). Investigation using sequential sections revealed that the distribution of these fine crystallites (Figure 4f) overlaps with the surface region showing reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody (Figure 4g). Reaction with the anti-ENAM antibody was not significant in the acrodin matrix; a higher density of PAG particles were found when phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was used as the negative control but not found when normal rabbit serum (NRS) was used (Figures 4h and S2E, F). This result does not support our LM analysis (Figure 3d) probably because, at least in part, the marginal reactivity detected in LM was diluted in ultrathin sections used in TEM (section thickness: 350 nm in LM and 70 nm in TEM).

2.4. TEM analysis of collar ganoin matrix formation

In the secretory stage of collar ganoin formation, reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected in the collar ganoin matrix and granules within IDE cells (Figure 4i, j). More scattered PAG particles were also detected on collagen fibrils in the dentin matrix, adjacent to the border with collar ganoin (Figure 4j). As in LM, reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody in the collar ganoin matrix was found mostly along the surface (Figure 4k). Reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody was also found in granules within IDE cells (Figure 4k). Using the anti-ENAM antibody, reactivity was detected throughout the collar ganoin matrix (Figure 4l). Negative controls are provided in supporting information (Figure S2G, H).

2.5. TEM analysis of scale bone and ganoin mineralization and matrix formation

We investigated the initial formation of the ganoin matrix (Figure 3i). In the presecretory stage (before ganoin matrix layer formation), electron-dense islands (mineral foci) appeared in the surface zone, immediately beneath IGE cells, and in the slightly deeper subsurface zone within the bone matrix (Figure 5a). The bone mineral foci in the surface zone aggregated and increased in size (Figure 5b). The matrix that composes the ganoin layer was subsequently secreted by IGE cells (Figure 5c). The initial ganoin matrix was detected as radiated mineral ribbons, accommodated in hemispheres formed on the surface of IGE cells (Figure 5d) (Sire, 1994). In the middle secretory stage, the ganoin layer is filled with mineral ribbons, which run parallel to each other and perpendicular to the distal membrane of IGE cells (Figure 5e) (Sire, 1994). These mineral ribbons formed mineral bundles, extending from mammillary knobs (Figure 5e) (Sasagawa et al., 2016). Each mammillary knob corresponds to an aggregate of bone mineral foci. Some of these mammillary knobs subsequently aggregated, and extending mineral bundles integrated into thicker mineral bundles. We consider that these thick mineral bundles are responsible for the formation of the protoprismatic structure of ganoin (Sasagawa et al., 2016), which resembles the prismatic structure of mammalian enamel (Ørvig, 1978; Smith, 1989). Deep in the subsurface zone of the bone matrix, mineral foci coalesced into a continuous mineral layer (Figure 5e). These two bone mineral layers were separated by a narrow mineral foci-free zone.

Figure 5.

Transmission electron micrographs showing mineralization of bone and ganoin in scales (a-e) and immunohistochemical analysis of scale formation (f-p) in spotted gar. In the presecretory (a, b), early secretory (c, d), and middle secretory (e) stages of scale ganoin formation, mineral foci are found in the surface zone (SZ; near IGE cells) and the subsurface zone (SSZ) of the bone matrix (B). An overview (a) and an enlarged view of SZ (b) are shown. The ganoin matrix is initially secreted from IGE cells as radiated mineral ribbons accommodated in hemispheres (arrow in c and d). (e) In the middle secretory stage, numerous mineral ribbons, running perpendicular to IGE cells in the ganoin matrix (SG), form bundles that extend from mammillary knobs (arrow). (f-j) The early (f-i) and middle (j) secretory stages of scale ganoin formation were analyzed using the anti-SCPP5N antibody. The positions shown by “#” and “*” in the overview (f) are enlarged (“#” in g and “*” in h). (g) Note that collagen fibers are arranged perpendicular to the distal membrane of IGE cells (arrow). (j) In the middle secretory stage, SZ and SSZ in the bone matrix (B) are separated by a narrow mineral loci-free zone. The early (k), middle (l), and late (m) secretory stages of scale ganoin formation were analyzed using the anti-AMBN antibody. PAG particles were significantly detected only in the late secretory stage in SG near the distal membrane of IGE cells (open arrow). The early (n) and middle (o and p) secretory stages of scale ganoin formation were analyzed using the anti-ENAM antibody. Two different regions (outer region in o; inner region in p) are shown for the middle secretory stage. Negative controls are shown in Figure S2 (K and L). Sections were stained with TI-Pb-PTA. Scale bars: 2.0 μm (a, and e-i), 1.0 μm (b, j, and l), 500 nm (c, d, k, and m-p).

In the early secretory stage, although mineral is removed during our immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, electron-dense clumps were detected in the surface and subsurface zones of the bone matrix (Figure 5f; regions around # and * are enlarged in Figure 5g, h), and electron-dense radiated fibrils were found in hemispheres on the surface of IGE cells (Figure 5i). Their configurations and morphological similarities indicate that these clumps and radiated fibrils are organic materials associated respectively with mineral foci and mineral ribbons (Figure 5a–d), generally known as “ghosts” (Kallenbach, 1986; Bonucci, 2014). Reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected in electron-dense clumps present in the surface (Figure 5g) and subsurface (Figure 5h) zones of the bone matrix but not in the intervening electron-lucent zone (Figure 5g). Positive reactivity was also detected in hemispheres (Figure 5i). In the middle secretory stage, reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was found in the ganoin layer and in the surface and subsurface zones of the bone matrix (Figure 5j). The electron-lucent zone in this stage was narrower than that in the early secretory stage (Figure 5f). At higher magnification, most PAG particles were found in association with electron-dense fibrils (Figure S2I). Many PAG particles were also detected in granules within IGE cells and in their intracellular space (Figure S2J).

In the early (Figure 5k) and middle (Figure 5l) secretory stages, no reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody was detected in the bone or ganoin matrix. Significant reactivity was detected subsequently in the late secretory stage, when the bulk of the ganoin layer is formed. PAG particles were present principally in a narrow surface region of the ganoin matrix (Figure 5m). Reactivity with the anti-ENAM antibody was detected in hemispheres secreting the initial ganoin matrix (Figure 5n). Additionally, lower reactivity was found in the electron-dense surface zone in the bone matrix (Figure 5n). In the middle secretory stage, reactivity with anti-ENAM antibody was detected throughout the ganoin matrix and in the surface zone (Figure 5o, p). Most PAG particles were associated with electron dense fibrils (Figure 5o). Negative controls are provided in supporting information (Figure S2K, L).

3. DISCUSSION

3.1. Structural characteristics of SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM conserved in bichirs and gars

We showed that structural characteristics of SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM are highly conserved in bichirs and gars but significantly changed in teleosts, even though the divergence time of bichirs, gars, and teleosts from their common ancestor is the same, ~380 Ma (Hughes et al., 2018). It is likely that highly conserved structural characteristics of scpp5, ambn, and enam in bichirs and gars reflect ancient characters of ganoin on both scales and teeth retained only in these two families of actinopterygians (Sasagawa et al., 2013). Significant changes in structural characteristics of teleost scpp5, ambn, and enam genes are partly due to frequent exon deletion. Because exon deletion in scpp5, ambn, and enam was less frequent in Atlantic tarpon among teleosts, their structural characteristics are relatively well conserved in their Atlantic tarpon orthologs (Figure S1).

3.2. Similarities in the formation of acrodin and scale ganoin

Among the hypermineralized tissues of spotted gar, acrodin begins mineralization in a preassembled collagen-rich matrix (Sasagawa and Ishiyama, 2005a), like bone and dentin. During acrodin formation, reactivity with the anti-SCPP5N antibody was detected only in the middle mineralization stage (Figure 4a–d). In LM, individual PAG particles were identifiable in the acrodin matrix (Figure 3b), which is in contrast with the PAG particles that are densely packed in the collar and scale ganoin matrices (Figure 3f, j). The relatively lower density of PAG particles in the acrodin matrix presumably reflects the fact that collagen fibrils occupy most of the space in the matrix. Scpp5 is therefore secreted by epithelial cells into the collagen-rich acrodin matrix at a lower level than into the ganoin matrix before mineralization begins along collagen fibrils in the late mineralization stage. This process resembles the presecretory stage of scale ganoin formation in spotted gar. In the early secretory stage of ganoin formation, Scpp5 was detected in electron-dense clumps formed in both the surface and subsurface zones of the bone matrix (Figure 5f–h), whereas Enam was found only in the surface zone (Figure 5n). This result suggests that Scpp5 is secreted initially into the bone matrix in the presecretory stage earlier than Enam and that the secretion of Enam begins immediately before the onset of the secretory stage. The presecretory stage is followed by the formation of the ganoin layer through upregulation of matrix secretion (Figure 3i) (Sire, 1994; Sasagawa et al., 2016). By contrast, in the subsequent stage of acrodin formation, Scpp5 was not detected in the matrix (Figure 4d), which implies downregulation of the secretion and enzymatic processing of Scpp5. This phase is like the maturation stage of enamel formation, when the organic components are removed from the matrix (Robinson, 2014; Nanci, 2017). Acrodin formation thus resembles the presecretory and maturation stages of ganoin formation, which suggests that acrodin evolved by the loss of the secretory stage of ganoin formation. This view advances the previous heterochrony hypothesis about the origin of acrodin or enameloid in actinopterygians (Smith, 1992; Smith, 1995; Kawasaki et al., 2021) and supports the proposition that enameloid is a dentin-like hypermineralized tissue (Poole, 1967; Kogaya, 1999).

Similar processes are also found during tooth enameloid formation in larvae of the Iberian ribbed newt; the expression of the type-I collagen gene begins earlier than weak AMEL expression (Assaraf-Weill et al., 2014). Furthermore, during enameloid formation in larvae of the Japanese fire belly newt, ameloblasts secrete AMEL-like proteins after collagen matrix formation (Kogaya, 1999). Independent evolution of enameloid (acrodin) in actinopterygians and urodeles with enamel (ganoin)-bearing teeth could be explained by the common processes in enameloid formation and in the presecretory and maturation stages of enamel formation. This hypothesis is also consistent with the collar enameloid formation in European eel; non-collagenous proteins secreted by IDE cells diffuse into the preformed enameloid matrix (Shellis and Miles, 1974). This study, however, further argues that these non-collagenous proteins subsequently form an enamel layer. Further study is needed to elucidate collar enameloid formation in teleosts.

Enameloid is also found in teeth and scales of elasmobranchs (Poole, 1967; Sire et al., 2009). It was reported that epithelial cells overlying teeth and scales express two genes that are evolutionarily related to SCPP genes (Leurs et al., 2022). However, none of these genes are orthologous to AMEL, SCPP5, AMBN, ENAM, or any other true SCPP genes, which is consistent with the hypothesis that chondrichthyan enameloid is distinct from enamel and enameloid of osteichthyans (Sasagawa, 2002).

3.3. Similarities and differences in the formation of collar ganoin and scale ganoin

The newly formed layer of scale ganoin was referred to as “preganoin” (Kerr, 1952; Thomson and McCune, 1984), which was regarded as “a layer of unmineralized ganoin matrix” (Sire, 1994). Like dental enamel in mammals, however, this layer is composed of mineral ribbons (Sire, 1994; Sasagawa et al., 2016), which continuously elongate near the distal membrane of IGE cells, and does not require preassembled matrix for mineralization (Nanci and Warshawsky, 1984; Fincham et al., 1999). In the present study, the newly formed scale ganoin layer is not considered “preganoin,” as no “preenamel” layer forms during enamel formation (Nanci, 2017).

The formation of collar ganoin resembles scale ganoin formation. Epithelial cells initiate matrix protein secretion in the presecretory stage, and mineral ribbons are subsequently formed perpendicular to the distal membrane of epithelial cells (Prostak et al., 1989; Sasagawa et al., 2008). Furthermore, the distribution of Scpp5, Ambn, and Enam in the matrix is indistinguishable during the formation of collar ganoin and scale ganoin in spotted gar (Figure 3). This result confirms that the collar tissue is referred to better as collar ganoin (Ørvig, 1978; Richter and Smith, 1995), rather than collar enamel, in spotted gar (Kawasaki et al., 2021) and probably also in bichirs because gars and bichirs possess similar scpp5, ambn, and enam genes.

Despite these similarities, however, the collar ganoin matrix initiates mineralization after the matrix forms an unmineralized layer (Sasagawa et al., 2008; Sasagawa et al., 2019). This process significantly differs from the formation of scale ganoin and mammalian enamel, in which mineralization begins concurrently with the initial formation of the matrix layer (Figure 5a–d) (Rönnholm, 1962a; Rönnholm, 1962b; Smith et al., 2016). At the onset of the scale ganoin formation in spotted gar, like enamel formation in mammals, mineral foci appear in the matrix of the underlying tissue, where collagen bundles are arranged perpendicular to the distal membrane of epithelial cells (Figure 5g) (Sire, 1994). During tooth formation, by contrast, extremely thick collagen bundles are arrayed parallel to the distal membrane of epithelial cells (Figures 4l and S2G) (Sasagawa et al., 2019). Mineralization of dentin progresses along these collagen bundles initially away from the dentin-ganoin junction. Furthermore, no mineral foci are found. Mineralization of the collar ganoin matrix begins when mineralization along the collagen bundles reaches underneath the junction with the ganoin matrix (Prostak et al., 1989; Sasagawa et al., 2019). We thus do not consider that mineralization of collar ganoin requires a preformed matrix in spotted gar, but that the initial mineralization of collar ganoin is delayed because of slow growth of dentin mineralization along the junction with ganoin. Indeed, once mineral ribbons form, they elongate immediately underneath the distal membrane of epithelial cells (Figure 4l) (Prostak et al., 1989; Sasagawa et al., 2019). In addition, unlike scale ganoin formation, the presence of mammillary knobs is not evident during collar ganoin formation (Sasagawa et al., 2019). Presumably for this reason, the protoprismatic structure (Ørvig, 1978; Smith, 1989) is unclear in collar ganoin. Collar ganoin is not identical to scale ganoin in spotted gar.

3.4. Similarities and differences in matrix proteins of gar ganoin and amniote enamel

During enamel formation in mammals and caimans, antibodies against middle or C-terminal portions of AMBN detect the surface region of the enamel matrix, whereas antibodies against N-terminal portions of AMBN, such as M-1 antibody, react broader regions (Hu et al., 1997b; Murakami et al., 1997; Uchida et al., 1997; Shintani et al., 2006). This discrepancy is attributed to rapid enzymatic processing of the middle to C-terminal portions of AMBN (Murakami et al., 1997; Uchida et al., 1997). Although our anti-AMBN antibody detects an N-terminal portion, like M-1 antibody, its reactivity was found in the surface region of the ganoin matrix. This finding suggests that enzymatic processing of AMBN differs during ganoin formation in spotted gar and during enamel formation in mammals and caimans. Yet this difference is also likely due to a late onset of AMBN secretion (see below).

As described above, our result suggests that the secretion of Scpp5 begins in the presecretory stage earlier than that of Enam. Similarly, during mammalian tooth formation, AMEL appears in predentin earlier than AMBN and ENAM (Nanci et al., 1989; Uchida et al., 1991a; Nanci et al., 1998). The early secretion of Scpp5, thus, corroborates the similarity of SCPP5 and AMEL. AMEL is thought to separate and support the mineral ribbons (Simmer et al., 2021). SCPP5 may have a similar function, and the accumulation of AMEL and SCPP5 before mineral ribbon formation may secure the onset of appositional growth of the enamel matrix. However, SCPP5 also shows features that differ from AMEL. In mammals, electron-dense patches containing AMEL appear in predentin, but most of these patches do not coexist with mineral foci (Kallenbach, 1971; Smith et al., 2016). Moreover, many matrix vesicles are found in predentin near ameloblasts (Nanci et al., 1989; Sasaki and Garant, 1996; Smith et al., 2016), whereas no matrix vesicles are detected in the scale bone matrix near IGE cells in spotted gar (Figure 5b, c) (Sire, 1994; Sasagawa et al., 2016). It is thus possible that Scpp5 is involved in mineralization of bone collagen fibrils in ganoid scales of spotted gar.

3.5. Distinct roles of AMBN and ENAM in the ganoin matrix

It is proposed that both AMBN and ENAM are part of the apparatus that molds appositionally growing mineral ribbons and secures the attachment of mineral ribbons to the ameloblast membrane (Simmer et al., 2021). This proposition is largely based on gene targeting studies, showing that both AMBN and ENAM are required for mineral ribbon formation (Fukumoto et al., 2004; Wazen et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2016; Liang et al., 2019). These studies, however, do not resolve distinct roles of AMBN and ENAM because Ambn-disrupted mice and Enam-disrupted mice exhibit similar phenotypes.

During scale ganoin formation in spotted gar, by contrast, Ambn was initially detected by TEM in the late secretory stage (Figure 5k–m). This result is supported by our LM analysis; PAG particles were detected only in a developmentally advanced region of the scale (Figure 3k). No significant reactivity with the anti-AMBN antibody in the early or middle secretory stage implies that Ambn is not involved in the initial mineral ribbon formation. Moreover, the late onset of Ambn secretion suggests that the function of this protein is restricted to the surface region of the ganoin matrix. During acrodin formation, Ambn colocalizes with crystallites in the surface region of the fully formed collagen matrix (Figure 4f, g). While this result suggests that Ambn interacts with minerals also in the surface region of the fully thickened ganoin matrix, specific functions of ambn remain unresolved. It is notable, however, that ambn and enam have distinct roles in spotted gar.

Unlike Ambn, Enam was found along with initial mineral ribbons in hemispheres (Figure 5n), which is consistent with the proposition that Enam participates in molding mineral ribbons and securing the attachment of mineral ribbons to epithelial cells (Simmer et al., 2021). In mammals, the interaction of Enam with minerals is mediated by a small region (known as the 32-kDa enamelin) that contains two or more pSer residues, encoded by the last three pc-exons (Tanabe et al., 1990; Fan et al., 2008; Al-Hashimi et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2010). A region corresponding to the 32-kDa enamelin is encoded by all ENAM orthologs studied to date (Figure 2) (Al-Hashimi et al., 2009; Kawasaki et al., 2021). Although various antibodies detect ENAM throughout the enamel matrix in mammals, the C-terminus of ENAM is detected only at the mineralization front, presumably because of rapid enzymatic processing of the C-terminus (Hu et al., 1997a). Similarly, although reactivity with the anti-ENAM antibody, raised against the 32-kDa enamelin-corresponding region, was not biased toward the surface (Figure 5o, p), intact Enam is probably present near epithelial cells before processing. Indeed, like ENAM of various sarcopterygians (except for some mammals) (Al-Hashimi et al., 2009; Al-Hashimi et al., 2010; Kawasaki and Amemiya, 2014), enam of non-teleost actinopterygians encodes an integrin-binding sequence (Figure 2), which can mediate the attachment of the enamel matrix to epithelial cells (Mohazab et al., 2013).

These findings agree that ENAM plays vital roles in mineral ribbon formation in both sarcopterygians and actinopterygians but do not necessarily support such roles for AMBN. Furthermore, SCPP5 resembles AMEL (Kawasaki et al., 2021) that is not important for the initial formation of mineral ribbons (Hu et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2016; Bartlett et al., 2021). It is thus likely that the evolution of ENAM was the crucial event for the origin of the unique mineralization process of the enamel matrix.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. Analysis of gene sequences

Orthologs of SCPP5, AMBN, and ENAM were identified in the genome sequences of non-teleost actinopterygians, as previously described (Mikami et al., 2022). The orthologs of these three genes in various teleosts, including Atlantic tarpon, were found in the GenBank database by searching sequence similarity with BLASTP (Altschul et al., 1990) using amino acid sequences encoded by already known genes as queries. Amino acid sequences encoded by scpp5, ambn, and enam in various non-teleost actinopterygians and teleosts and their GenBank accession numbers are shown in supporting information (Figure S1).

4.2. Histological analysis

Five spotted gar specimens (total length 16–55 cm) were used in accordance with the guideline approved by the institutional animal care and use committee; these specimens were sacrificed by decapitation after refrigeration in ice-cold water or anesthesia with ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate (Sigma-Aldrich). Their jaws and skin were removed, dissected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, and 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH7.4) for 3 hours at 4C, dehydrated with N, N-dimethylformamide, and embedded in LR White Resin (London Resin). For LM, semithin (350 nm) sections were made from LR White Resin blocks, mounted on glass slides, and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue (TB). For TEM, ultrathin (70 nm) sections obtained from LR-White Resin blocks were mounted on copper or nickel grids and stained with platinum blue (TI blue; Nissin EM) and/or lead citrate (Pb). Two sequential sections were used to examine the overlapping distribution of crystallites and Ambn (Figure 4f, g). Some sections were stained with TI-Pb and phosphotungstic acid (TI-Pb-PTA) (Sasagawa et al., 2019).

4.3. IHC analysis

We raised the anti-SCPP5N, anti-AMBN, and anti-ENAM polyclonal antibodies against spotted gar Scpp5 (near the N-terminus), Ambn, and Enam, respectively. The anti-SCPP5N antibody was described previously (Kawasaki et al., 2021). The anti-AMBN antibody and the anti-ENAM antibody were made using the His-Ala-Glu-Gln-Gln-Tyr-Glu-Tyr-Glu-Thr peptide and the Asn-Glu-Val-Asn-Glu-Lys-Glu-Ser-Glu-Ser peptide, respectively, as the antigen (Sigma-Aldrich).

The PAG method was used for our IHC analysis. For LM-IHC analysis, semithin sections were made from LR White Resin blocks, mounted on glass slides, immersed in 5% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS for 30 min, incubated with the relevant antibody (diluted 1:100 or 1:200 in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA-PBS)) at 4C overnight, washed with PBS, treated with 5% NGS for 15 min, incubated with PAG conjugate (5 nm gold; EMPAG5, BBI Solutions; diluted 1:100 with BSA-PBS) for 60 min, washed with PBS, treated with the silver enhancer solution (50 mM citrate buffer, 0.85% hydroquinone, 0.1% maleic acid, 0.11% silver lactate, and 1% acacia powder) (Uchida et al., 1991b) for 10 min in the dark, rinsed with distilled water, immersed in photographic fixative for 1 min, stained with 0.1% nuclear fast red, rinsed with distilled water, and air dried.

For TEM-IHC analysis, ultrathin sections obtained from LR White Resin blocks were mounted on nickel grids, floated on a drop of 1% NGS for 15 min, incubated on a relevant antibody (diluted 1:200– 1:400 with BSA-PBS) overnight, washed with PBS, treated with 1% NGS for 10 min, transferred onto a drop of the PAG conjugate (diluted 1:10 with BSA-PBS) for 30 min, stained with TI-Pb or TI-Pb-PTA, and examined in a TEM (JEM-1010; JEOL). In some sections, immunoreactions were enhanced by the intensification method using the silver enhancer solution (Uchida et al., 1991b) or the Silver Enhancer Kit (KPL) (Sasagawa et al., 2019). As negative controls, NRS or PBS (no antibody) was used (Figure S2A, B, E-H, K, L).

Supplementary Material

Research highlights.

The origin of acrodin can be explained by the loss of the matrix secretory stage of ganoin formation. During ganoin formation, ameloblastin secretion begins late, which suggests that enamelin was vital to the unique process of enamel mineralization.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

K. K. is grateful to Distinguished Prof. Joan T. Richtsmeier at Penn State University for encouragement to this work. This work was made possible by the fund from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE031439) to Distinguished Prof. Joan T. Richtsmeier, the Department of Anthropology at Penn State University to K. K., and grants from the Nippon Dental University (NDU Grants N-19014 and N-20012) to M. M.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplemental material of this article.

REFERENCES

- Al-Hashimi N, Lafont AG, Delgado S, Kawasaki K, & Sire J-Y (2010). The enamelin genes in lizard, crocodile, and frog and the pseudogene in the chicken provide new insights on enamelin evolution in tetrapods. Molecular Biology and Evolution 27:2078–2094. 10.1093/molbev/msq098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hashimi N, Sire J-Y, & Delgado S (2009). Evolutionary analysis of mammalian enamelin, the largest enamel protein, supports a crucial role for the 32-kDa peptide and reveals selective adaptation in rodents and primates. Journal of Molecular Evolution 69:635–656. 10.1007/s00239-009-9302-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, & Lipman DJ (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaraf-Weill N, Gasse B, Silvent J, Bardet C, Sire J-Y, & Davit-Béal T (2014). Ameloblasts express type I collagen during amelogenesis. Journal Dental Research 93:502–507. 10.1177/0022034514526236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JD, Smith CE, Hu Y, Ikeda A, Strauss M, Liang T et al. (2021). MMP20-generated amelogenin cleavage products prevent formation of fan-shaped enamel malformations. Scientific Reports 11:10570. 10.1038/s41598-021-90005-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonucci E (2014). Understanding nanocalcification: a role suggested for crystal ghosts. Marine Drugs 12:4231–4246. 10.3390/md12074231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch I, Gehrke AR, Smith JJ, Kawasaki K, Manousaki T, Pasquier J et al. (2016). The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates human-teleost comparisons. Nature Genetics 48:427–437. 10.1038/ng.3526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HC, Mai L, Oikonomopoulou A, Chan HL, Richardson AS, Wang SK et al. (2010). Altered enamelin phosphorylation site causes amelogenesis imperfecta. Journal of Dental Research 89:695–699. 10.1177/0022034510365662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng P, Huang Y, Lv Y, Du H, Ruan Z, Li C et al. (2021). The American paddlefish genome provides novel insights into chromosomal evolution and bone mineralization in early vertebrates. Molecular Biology Evolution 38:1595–1607. 10.1093/molbev/msaa326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D, Lakshminarayanan R, & Moradian-Oldak J (2008). The 32 kDa enamelin undergoes conformational transitions upon calcium binding. Journal Structural Biology 163:109–115. 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham AG, Moradian-Oldak J, & Simmer JP (1999). The structural biology of the developing dental enamel matrix. Journal of Structural Biology 126:270–299. 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Kiba T, Hall B, Iehara N, Nakamura T, Longenecker G et al. (2004). Ameloblastin is a cell adhesion molecule required for maintaining the differentiation state of ameloblasts. Journal of Cell Biology 167:973–983. 10.1083/jcb.200409077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC-C, Fukae M, Uchida T, Qian Q, Zhang CH, Ryu OH et al. (1997a). Cloning and characterization of porcine enamelin mRNAs. Journal of Dental Research 76:1720–1729. 10.1177/00220345970760110201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC-C, Fukae M, Uchida T, Qian Q, Zhang CH, Ryu OH et al. (1997b). Sheathlin: cloning, cDNA/polypeptide sequences, and immunolocalization of porcine enamel sheath proteins. Journal of Dental Research 76:648–657. 10.1177/00220345970760020501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC-C, Lertlam R, Richardson AS, Smith CE, McKee MD, & Simmer JP (2011). Cell proliferation and apoptosis in enamelin null mice. European Journal of Oral Sciences 119 Suppl 1:329–337. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00860.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Smith CE, Cai Z, Donnelly LA-J, Yang J, Hu JC-C et al. (2016). Enamel ribbons, surface nodules, and octacalcium phosphate in C57BL/6 Amelx−/− mice and Amelx+/− lyonization. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 4:641–661. 10.1002/mgg3.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes LC, Orti G, Huang Y, Sun Y, Baldwin CC, Thompson AW et al. (2018). Comprehensive phylogeny of ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) based on transcriptomic and genomic data. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115:6249–6254. 10.1073/pnas.1719358115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama M, Inage T, & Shimokawa H (1999). An immunocytochemical study of amelogenin proteins in the developing tooth enamel of the gar-pike, Lepisosteus oculatus (Holostei, Actinopterygii). Archives of Histology and Cytology 62:191–197. 10.1679/aohc.62.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama M, Inage T, & Shimokawa H (2001). Abortive secretion of an enamel matrix in the inner enamel epithelial cells during an enameloid formation in the gar-pike, Lepisosteus oculatus (Holostei, Actinopterygii). Archives of Histology and Cytology 64:99–107. 10.1679/aohc.64.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach E (1971). Electron microscopy of the differentiating rat incisor ameloblast. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 35:508–531. 10.1016/s0022-5320(71)80008-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach E (1986). Crystal-associated matrix components in rat incisor enamel. An electron-microscopic study. Cell and Tissue Research 246:455–461. 10.1007/BF00215908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K, & Amemiya CT (2014). SCPP genes in the coelacanth: tissue mineralization genes shared by sarcopterygians. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 322:390–402. 10.1002/jez.b.22546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K, Keating JN, Nakatomi M, Welten M, Mikami M, Sasagawa I et al. (2021). Coevolution of enamel, ganoin, enameloid, and their matrix SCPP genes in osteichthyans. iScience 24:102023. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.102023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K, Lafont AG, & Sire J-Y (2011). The evolution of milk casein genes from tooth genes before the origin of mammals. Molecular Biology and Evolution 28:2053–2061. 10.1093/molbev/msr020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K, Mikami M, Nakatomi M, Braasch I, Batzel P, Postlethwait JH et al. (2017). SCPP genes and their relatives in gar: rapid expansion of mineralization genes in osteichthyans. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 328:645–665. 10.1002/jez.b.22755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki K, & Weiss KM (2003). Mineralized tissue and vertebrate evolution: the secretory calcium-binding phosphoprotein gene cluster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 100:4060–4065. 10.1073/pnas.0638023100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T (1952). The scales of primitive living actinopterygians. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 122:55–78. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1952.tb06313.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kogaya Y (1999). Immunohistochemical localisation of amelogenin-like proteins and type I collagen and histochemical demonstration of sulphated glycoconjugates in developing enameloid and enamel matrices of the larval urodele (Triturus pyrrhogaster) teeth. Journal of Anatomy 195 (Pt 3):455–464. 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1999.19530455.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs N, Martinand-Mari C, Marcellini S, & Debiais-Thibaud M (2022). Parallel evolution of ameloblastic scpp genes in bony and cartilaginous vertebrates. Molecular Biology and Evolution 39. 10.1093/molbev/msac099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang T, Hu Y, Smith CE, Richardson AS, Zhang H, Yang J et al. (2019). AMBN mutations causing hypoplastic amelogenesis imperfecta and Ambn knockout-NLS-lacZ knockin mice exhibiting failed amelogenesis and Ambn tissue-specificity. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 7:e929. 10.1002/mgg3.929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami M, Ineno T, Thompson AW, Braasch I, Ishiyama M, & Kawasaki K (2022). Convergent losses of SCPP genes and ganoid scales among non-teleost actinopterygians. Gene 811:146091. 10.1016/j.gene.2021.146091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohazab L, Koivisto L, Jiang G, Kytömäki L, Haapasalo M, Owen GR et al. (2013). Critical role for αvβ6 integrin in enamel biomineralization. Journal of Cell Science 126:732–744. 10.1242/jcs.112599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradian-Oldak J (2012). Protein-mediated enamel mineralization. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 17:1996–2023. 10.2741/4034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami C, Dohi N, Fukae M, Tanabe T, Yamakoshi Y, Wakida K et al. (1997). Immunochemical and immunohistochemical study of the 27- and 29-kDa calcium-binding proteins and related proteins in the porcine tooth germ. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 107:485–494. 10.1007/s004180050136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A (2017). Ten Cate’s oral histology: development, structure, and function. St-Louis: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A, Ahluwalia JP, Pompura JR, & Smith CE (1989). Biosynthesis and secretion of enamel proteins in the rat incisor. The Anatomical Record 224:277–291. 10.1002/ar.1092240218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A, & Warshawsky H (1984). Relationship between the quality of fixation and the presence of stippled material in newly formed enamel of the rat incisor. The Anatomical Record 208:15–31. 10.1002/ar.1092080104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanci A, Zalzal S, Lavoie P, Kunikata M, Chen W, Krebsbach PH et al. (1998). Comparative immunochemical analyses of the developmental expression and distribution of ameloblastin and amelogenin in rat incisors. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 46:911–934. 10.1177/002215549804600806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Near TJ, Eytan RI, Dornburg A, Kuhn KL, Moore JA, Davis MP et al. (2012). Resolution of rayfinned fish phylogeny and timing of diversification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 109:13698–13703. 10.1073/pnas.1206625109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ørvig T (1978). Microstructure and growth of dermal skeleton in fossil actinopterygian fishes - Birgeria and Scanilepis. Zoologica Scripta 7:33–56. 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1978.tb00587.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DFG (1967). Phylogeny of tooth tissues: enameloid and enamel in recent vertebrates, with a note on the history of cementum. In Miles AEW (Ed.), Structural and Chemical Organization of Teeth (pp. 111–149). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prostak K, Seifert P, & Skobe Z (1989). Ultrastructure of developing teeth in the gar pike, (Lepisosteus). In Fernhead RW (Ed.), Tooth enamel V (pp. 188–192). Florence Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Qu Q, Haitina T, Zhu M, & Ahlberg PE (2015). New genomic and fossil data illuminate the origin of enamel. Nature 526:108–111. 10.1038/nature15259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M, & Smith M (1995). A microstructural study of the ganoine tissue of selected lower vertebrates. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 114:173–212. 10.1006/zjls.1995.0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C (2014). Enamel maturation: a brief background with implications for some enamel dysplasias. Frontiers in Physiology 5:388. 10.3389/fphys.2014.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnholm E (1962a). The amelogenesis of human teeth as revealed by electron microscopy. II. The development of the enamel crystallites. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 6:249–303. 10.1016/s0022-5320(62)80036-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rönnholm E (1962b). An electron microscopic study of the amelogenesis in human teeth. I. The fine structure of the ameloblasts. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 6:229–248. 10.1016/s0022-5320(62)90055-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I (2002). Mineralization patterns in elasmobranch fish. Microscopy Research and Technique 59:396–407. 10.1002/jemt.10219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, & Ishiyama M (2003). Fine structural observation of the initial mineralization during enameloid formation in gar-pikes, Lepisosteus oculatus, and Polypterus, Polypterus senegalus, bony fish. In Kobayashi I, & Ozawa H (Eds.), Biomineralization (BIOM2001): formation, diversity, evolution and application (pp. 381–385). Tokai University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, & Ishiyama M (2005a). Fine structural and cytochemical mapping of enamel organ during the enameloid formation stages in gars, Lepisosteus oculatus, Actinopterygii. Archives of Oral Biology 50:373–391. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, & Ishiyama M (2005b). Fine structural and cytochemical observations on the dental epithelial cells during cap enameloid formation stages in Polypterus senegalus, a bony fish (Actinopterygii). Connective Tissue Research 46:33–52. 10.1080/03008200590935538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Ishiyama M, Yokosuka H, & Mikami M (2008). Fine structure and development of the collar enamel in gars, Lepisosteus oculatus, Actinopterygii. Frontiers of Materials Science in China 2:134–142. 10.1007/s11706-008-0023-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Ishiyama M, Yokosuka H, & Mikami M (2013). Teeth and ganoid scales in Polypterus and Lepisosteus, the basic actinopterygian fish: an approach to understand the origin of the tooth enamel. Journal of Oral Biosciences 55:76–84. 10.1016/j.job.2013.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Ishiyama M, Yokosuka H, Mikami M, Oka S, Shimokawa H et al. (2019). Immunolocalization of enamel matrix protein-like proteins in the tooth enameloid of spotted gar, Lepisosteus oculatus, an actinopterygian bony fish. Connective Tissue Research 60:291–303. 10.1080/03008207.2018.1506446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Oka S, Mikami M, Yokosuka H, Ishiyama M, Imai A et al. (2016). Immunohistochemical and Western blotting analyses of ganoine in the ganoid scales of Lepisosteus oculatus: an actinopterygian fish. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 326:193–209. 10.1002/jez.b.22676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Yokosuka H, Ishiyama M, Mikami M, Shimokawa H, & Uchida T (2012). Fine structural and immunohistochemical detection of collar enamel in the teeth of Polypterus senegalus, an actinopterygian fish. Cell and Tissue Research 347:369–381. 10.1007/s00441-011-1305-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, & Garant PR (1996). Structure and organization of odontoblasts. The Anatomical Record 245:235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze H-P (2016). Scales, enamel, cosmine, ganoine, and early osteichthyans. Comptes Rendus Palevol 15:83–102. 10.1016/j.crpv.2015.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shellis RP, & Miles AEW (1974). Autoradiographic study of formation of enameloid and dentin matrices in teleost fishes using tritiated amino-acids. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 185:51–72. 10.1098/rspb.1974.0005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani S, Kobata M, Toyosawa S, & Ooshima T (2006). Expression of ameloblastin during enamel formation in a crocodile. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 306:126–133. 10.1002/jez.b.21077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer JP, & Fincham AG (1995). Molecular mechanisms of dental enamel formation. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology & Medicine 6:84–108. 10.1177/10454411950060020701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmer JP, Hu JC-C, Hu Y, Zhang S, Liang T, Wang SK et al. (2021). A genetic model for the secretory stage of dental enamel formation. Journal of Structural Biology 213:107805. 10.1016/j.jsb.2021.107805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sire J-Y (1994). Light and TEM study of nonregenerated and experimentally regenerated scales of Lepisosteus oculatus (Holostei) with particular attention to ganoine formation. The Anatomical Record 240:189–207. 10.1002/ar.1092400206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sire J-Y, Donoghue PC, & Vickaryous MK (2009). Origin and evolution of the integumentary skeleton in non-tetrapod vertebrates. Journal of Anatomy 214:409–440. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01046.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Hu Y, Hu JC-C, & Simmer JP (2016). Ultrastructure of early amelogenesis in wild-type, Amelx(−/−), and Enam(−/−) mice: enamel ribbon initiation on dentin mineral and ribbon orientation by ameloblasts. Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 4:662–683. 10.1002/mgg3.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM (1989). Distribution and variation in enamel structure in the oral teeth of sarcopterygians: its significance for the evolution of a protoprismatic enamel. Historical Biology 3:97–126. 10.1080/08912968909386516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM (1992). Microstructure and evolution of enamel amongst osteichthyan fishes and early tetrapods. In Smith P, & Tchernov E (Eds.), Structure, Function, and Evolution of Teeth (pp. 73–101). Freund Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM (1995). Heterochrony in the evolution of enamel in vertebrates. In McNamara KJ (Ed.), Evolutionary Change and Heterochrony (pp. 125–150). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabracci VS, Engel JL, Wen J, Wiley SE, Worby CA, Kinch LN et al. (2012). Secreted kinase phosphorylates extracellular proteins that regulate biomineralization. Science 336:1150–1153. 10.1126/science.1217817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T, Aoba T, Moreno EC, Fukae M, & Shimuzu M (1990). Properties of phosphorylated 32 kd nonamelogenin proteins isolated from porcine secretory enamel. Calcified Tissue International 46:205–215. 10.1007/BF02555046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson KS, & McCune AR (1984). Development of the scales in Lepisosteus as a model for scale formation in fossil fishes. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 82:73–86. 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1984.tb00536.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toyosawa S, O’Huigin C, Figueroa F, Tichy H, & Klein J (1998). Identification and characterization of amelogenin genes in monotremes, reptiles, and amphibians. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 95:13056–13061. 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Murakami C, Dohi N, Wakida K, Satoda T, & Takahashi O (1997). Synthesis, secretion, degradation, and fate of ameloblastin during the matrix formation stage of the rat incisor as shown by immunocytochemistry and immunochemistry using region-specific antibodies. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 45:1329–1340. 10.1177/002215549704501002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Tanabe T, Fukae M, & Shimizu M (1991a). Immunocytochemical and immunochemical detection of a 32 kDa nonamelogenin and related proteins in porcine tooth germs. Archives of Histology and Cytology 54:527–538. 10.1679/aohc.54.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T, Tanabe T, Fukae M, Shimizu M, Yamada M, Miake K et al. (1991b). Immunochemical and immunohistochemical studies, using antisera against porcine 25 kDa amelogenin, 89 kDa enamelin and the 13–17 kDa nonamelogenins, on immature enamel of the pig and rat. Histochemistry 96:129–138. 10.1007/BF00315983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B, Lee AP, Ravi V, Maurya AK, Lian MM, Swann JB et al. (2014). Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505:174–179. 10.1038/nature12826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wazen RM, Moffatt P, Zalzal SF, Yamada Y, & Nanci A (2009). A mouse model expressing a truncated form of ameloblastin exhibits dental and junctional epithelium defects. Matrix Biol 28:292–303. 10.1016/j.matbio.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worby CA, Mayfield JE, Pollak AJ, Dixon JE, & Banerjee S (2021). The ABCs of the atypical Fam20 secretory pathway kinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry 296:100267. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplemental material of this article.