Abstract

Digital inclusion (DI) represents a framework for educational leaders to address ongoing digital access and participation divides for adult caretakers (e.g., parents) of school-aged children, as schools continue adopting new education technology tools. This preliminary research investigates teacher perceptions of different DI needs for parents during the pandemic. This research examines teacher perceptions of parents’ knowledge and use of online tools in providing supervision to support home-based learning for their student children. A sample of K-12 teachers in the United States responded to open-ended survey questions relating to their observation and evaluation of student learning, parent involvement, and DI needs in their classes. The researchers used a framework drawn from Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to categorize key DI components teachers identified, finding both digital access and digital participation needs existed in their students’ homes. Ultimately, the framework of DI recognizes that household digital access alone does not create equitable opportunities for online instruction without holistic consideration of digital literacy training, technical support, and relevant online tools for parents and caretakers.

Keywords: Digital Divide, Digital Inclusion, Family Engagement, Home-based Learning

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic brought increased attention to a digital divide that exists between families who have access to information communication technologies (ICTs) and those who do not (Pierce, 2018). The relationship between computer access and family income, race, and education among American families has been recognized for decades (Marks & Kominski, 1988). These inequalities (both systemic and resulting from slow diffusion from urban to rural communities) related to computer ownership and internet access have magnified the role of schools to provide the primary exposure and skills training of new ICTs (Helsper, 2021).

In academic research, the digital divide has since shifted to consider both differences in digital access and in online skills as similar levels of ICT access have resulted in different levels of digital participation and resulting benefits (Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk & Hacker, 2003). This disparity has been referred to as the usage gap and second-level digital divide as well as emerging digital differentiation and the digital participation divide. The disparity focused on physical ICT access has been referred to as the first-level digital divide as well as the digital access divide.

However, government, education, and for-profit institutions have traditionally focused on the digital access divide rather than the digital participation divide. During the COVID -19 pandemic, there has been a challenge in balancing responses to the urgent, short-term needs that the pandemic presents—such as hotspot and device distribution for Home Based Learning (HBL)—with ensuring a long-term, sustained investment in broadband adoption and digital literacy for families (Rhinesmith & Kennedy, 2020).

HBL was initially the practice of parents or caretakers assuming responsibility for the education of their student children outside of the conventional school system (Conradie, 2016). The widespread adoption of ICTs such as the internet and computer devices and the influence of the pandemic give new meaning to HBL, which refers to the practice that takes place when the teacher and students attend in separate locations but synchronous and asynchronous learning occurs with ICT tools (Wen et al, 2021). With varying ideologies and conclusions among scholars regarding frameworks of how families should be involved, including which aspects tie to improvements in children’s academic outcomes, the alignment between parent involvement and evolving ICTs in K-12 schools remains a challenge.

Digital Access and Participation Divides

Digital access divides describe how groups experience uneven opportunities to the physical access of information communication technologies, including internet and computer devices (van Dijk, 2006). With increasing technological advances, the access divide is currently underscored by increasing broadband speeds (Hilbert, 2016) and new capabilities and features in computer devices and smartphones. As each innovation in ICTs creates an advantage for those who can access and afford them, a perpetual disadvantage remains for those who cannot afford to be “early adopters” or in the “early majority” (Rogers, 1983), underscoring how digital access divides reflect deeper socio-economic divides. Furthermore, the compounded disadvantages from being in the “late majority” or “laggard” over multiple technological advances result in an exacerbated gap in socio-economic opportunities for those negatively impacted by the digital divide.

Students and their families with only smartphone access and cellular data plan suffer compared to their classmates and their families who have a laptop, desktop, or tablet at home (Hampton et al., 2020). Smartphones often do not have sufficiently large screens or keyboards to facilitate a greater range of opportunities such as reading from e-textbooks, taking online tests, learning to code, using editing and design software, utilizing accessibility aids, or accessing website resources not formatted for mobile phones (Ravi, 2020). Families without access to larger devices have fewer opportunities to explore new ideas, reinforce concepts from school, and hone new skills (Hollingworth et al., 2011). However, bridging these digital access divides alone does not adequately ensure equitable educational opportunities for these students and their families.

With different levels of internet (e.g., speed, bandwidth, stability) and device (e.g., size, availability) access enabling different levels of digital participation, the digital divide has shifted to consider both differences in digital access and online skills (Hargittai, 2002; van Dijk & Hacker, 2003). Van Dijk and Hacker (2003) and Hargittai (2002) describe how groups may gain similar access to information communication technologies but attain different levels of benefit from them as a result of varying levels of usage, training, literacies, and other factors. This disparity has been referred to as the usage gap and second-level digital divide, as well as emerging digital differentiation and the digital participation divide.

The Framework of Digital Inclusion

In the mid-2000s, the term “digital inclusion” became widely used among media and researchers, to jointly identify the challenges and subsequent framework to address the digital access and participation divides. Crandall and Fisher (2009) assert that digital inclusion goes beyond addressing the digital access divide; it means technological literacy and the ability to access relevant online content and services. Hache and Cullen (2009) extend the definition by arguing that digital inclusion democratizes access to ICTs to allow for the inclusion of the marginalized in society. Over time, digital inclusion has been described by practitioners and institutions as a “three-legged stool” that includes addressing internet, computer device, and digital literacy education access.

The term digital divide has continued to be widely used in the media and policy sphere. The use of this term has not adequately acknowledged the dynamic nature of digital inclusion, but rather, has contributed to an ongoing framing of divides that has historically emphasized physical access over digital skills and literacies.

In 2017, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA) convened practitioners and stakeholders nationwide to reevaluate how they operationalize this term. They defined digital inclusion as follows:

Digital Inclusion refers to the activities necessary to ensure that all individuals and communities, including the most disadvantaged, have access to and use of Information and Communication Technologies. This includes 5 elements: 1) affordable, robust broadband internet service; 2) internet-enabled devices that meet the needs of the user; 3) access to digital literacy training; 4) quality technical support; and 5) applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation, and collaboration. Digital Inclusion must evolve as technology advances. Digital Inclusion requires intentional strategies and investments to reduce and eliminate historical, institutional and structural barriers to access and use technology.

The use of digital inclusion as a framework has begun to shift the paradigm away from a binary conceptualization of internet and computer access portrayed through the term digital divide (Correa, 2008). Recognizing technological innovations will continue, digital inclusion represents a framework that transcends any particular ICT. Instead, the framework recognizes the inevitability of a technology adoption curve and the need for intentional strategies and investments to ensure vulnerable communities have the physical access and skills to thrive in an increasingly digital world.

Digital Inclusion as a Pandemic Response

During the coronavirus pandemic, improving home internet and device internet access has become a necessity for basic survival and increasing a family’s ability to self-isolate during the public health crisis (Chiou & Tucker, 2020). Amidst widespread directives during the SARS-Cov-2 pandemic, addressing digital access divides for K-12 students became recognized as increasingly essential for increasing HBL opportunities. Resultantly, emergency response efforts from the government and education institutions primarily focused on providing internet and device access for students without adequate consideration of parents and caretakers’ role in HBL. Further, many schools still lack capacity and resources to address DI needs of parents and caretakers when addressing student participation in digital learning.

Parent Involvement and Student Achievement

At the dawn of the Third Industrial Revolution, the emergence of computers and the Internet was instrumental in transforming ways of communication and learning for families and schools. During the same period, the Coleman Report was released and was paramount in changing the status quo that school and home processes do and should operate in isolation (Coleman, 1988). These two paradigm shifts separately increased the visibility of the role of parent involvement and digital inclusion as inputs for academic student achievement.

Currently, there is broad consensus regarding the existing relationship between parent involvement and student achievement; however, the magnitude of the impact of parent involvement varies. This variation can be explained by the varying ideologies and stances about how parents should be involved and about which aspects of parental involvement relate to improvements in children’s academic outcomes. These varying ideologies also explain the different terms used for parent involvement, including parental participation, parental engagement, and family engagement.

Varying frameworks on parent involvement reflect competing ideologies. Green et al. (2007) identify two types of parent involvement— home-based involvement (helping with homework or being aware of grades) and school-based involvement (attending parent-teacher conferences and performances). These types of frameworks provide characteristics that are more easily observable and measurable but do not capture all that parents and families do for their student children. Joyce Epstein’s (1995) typology of parent involvement includes six components: Parenting, Communicating, Volunteering, Learning at Home, Decision Making, Collaborating with the Community. While many frameworks contain similar elements, Epstein’s seminal work represents an ideology that recognizes providing for a child’s basic needs as a form of parent involvement in a child’s education, recognition that validates the efforts of parents who cannot be involved through traditional means identified in other frameworks.

The breadth of these frameworks in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century has strengthened the findings of meta-analyses in the field conducted in the past twenty years. The results of meta-analyses indicate that, in general, statistically significant relationships exist between parental involvement and academic achievement (e.g., Fan & Chen, 2001; Jeynes, 2005; Hill & Tyson, 2009). In Fan and Chen (2001), the conducted meta-analysis of 22 empirical studies distilled a wide range of characteristics and indicators to synthesize a definition of parent involvement to include the following: (a) contact with the school, (b) educational aspirations, (c) parent–child communication, (d) home supervision. Boonk et al. (2018) conducted a review of 75 studies published between 2003 and 2017, identifying correlations with academic achievement and these four variables: (a) reading at home, (b) parents that hold high expectations/aspirations for their children’s academic achievement and schooling, (c) communication between parents and children regarding school, (d) parental encouragement and support for learning.

From Parent Involvement to Family Engagement

As the relationship between parent involvement and student academic achievement has become more established, education policies in the twenty-first century have advanced and increasingly advocated to address barriers and create opportunities for meaningful parent involvement. Such policies have focused on a more holistic understanding of parent involvement that emphasizes “open parent-school communication” and the understanding that both parties bear responsibility for meaningful and consistent communication (Adams, 2016).

Mapp and Kuttner’s (2013) Dual-Capacity Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships recognizes the need for a mutual partnership between the teacher and family. In asserting a shift from parent involvement to family engagement, Mapp and Kuttner both recognized the role of other family members in a student’s educational journey and success. She also recognizes the term engagement derives from the Latin engare (meaning a contract or formal agreement), emphasizing how the family’s commitment to the student’s success forms a necessary component of family-school partnerships.

Digital Inclusion as an Input for Family Engagement

The dual-capacity building framework underscores the importance of instilling commitment in both families and teachers to develop the necessary skills to help students succeed academically. As the role of ICTs has become increasingly essential in facilitating digital learning, digital literacy skills for parents, in particular, have become a more recognized input for family engagement.

Despite the strong alignment between digital inclusion and parent involvement, many schools lack policies or statutory requirements to ensure access to adequate digital literacy training and technical support for parents and caretakers. In circumstances where the parent does not have adequate digital literacy skills, children often serve as “brokers,” mediating their parents’ connection to schools and assisting them in the use of digital tools (Correa, 2014; Katz, 2010). Families’ dependence on their child to navigate digital tools for school can put a strain on the parent–child relationship, disrupting traditional structures of power and control within the home (Correa, 2014).

The dynamic nature of the dual-capacity framework may enable teachers and schools to work as partners with families to ensure they have adequate ICT access and digital skills to support HBL. As schools and teachers adopt various LMS platforms and other software and hardware, commensurate digital literacy training and technical support can provide necessary skills for parents and caretakers to more effectively monitor, support, and encourage their child. Conversely, when parents and caretakers adopt different ICTs for communication than schools, teachers and schools must/can approach their communication strategy with both a culturally responsive and asset-based lens (Mapp & Kuttner, 2013).

Methods

No current body of research exists that examines the relationship between the framework of digital inclusion (DI) and family engagement in K-12 schools. Thus, this study utilizes teacher perceptions of K-12 family engagement through the lens of DI to evaluate the role of specific DI needs in facilitating parent engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the researchers explored the following question: From the perspective of teachers, how did different components of digital inclusion factor into parent engagement via home-based learning during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic? In order to answer this question, the researchers analyzed open-ended responses to a survey of teachers through an exploratory analysis guided by the DI framework (Creswell, 2014).

Research Design

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many states were experiencing public health orders and directives to stay at home or limit social interactions. Families across socioeconomic and racial backgrounds faced extraordinary challenges related to housing stability, food security, job loss, physical and mental health, and isolation. Ultimately, while both families and teachers had increased stressors, this study’s findings are focused and limited to teachers’ perceptions of K-12 family engagement rather than firsthand experiences of parents and other caretakers. While this design bias is significant, identifying a representative sample of families would have undermined the privacy and wellbeing of vulnerable families during a global public health crisis.

We worked with an initiative named Teachers4Research that has a pool of over 1,000 teachers in the United States that opted to learn about opportunities to participate in research studies. This same pool received the initial survey administered in May 2020. There was no compensation for participation in the survey. The survey was intentionally distributed to this pool at the end of September 2020 to accommodate late starts due the COVID-19 pandemic and to ensure teachers had additional experiences in a new school year to inform their responses. Over a two- and half-week period, a total of 113 survey responses were recorded, including 94 respondents who completed the survey.

The number of open-ended questions were limited, so the survey could be completed in about 10 min. After the required consent and initial background question, the remaining questions were optional and didn’t have a forced validation. Because this survey was a follow-up survey to a prior survey administered in May 2020, we had already received IRB approval to conduct a follow-up with modifications as long as the modifications didn’t affect the exempt determination or substantially change the focus of the study. The survey included the following sections:

Introduction and Consent (1 Question)

Background of Teacher (6 Questions)

Online Instruction (7 Questions)

Digital Inclusion and Family Engagement (5 Questions)

Voice, Stress, and Trap Questions (6 Questions)

Demographics of Teacher (4 Questions)

The three open-ended questions discussed from the survey are:

Question A: What reasons best explain the differences in student engagement levels in online instruction? [Select all that apply]

-

I.

Student motivation

-

II.

Student lack of parent engagement and support

-

III.

Student lack of parent supervision or childcare

-

IV.

Student internet access

-

V.

Student stress

-

VI.

Student access to technology (devices, printers, etc.)

-

VII.

Lack of classmate and peer interaction

-

VIII.

Lack of teacher interaction

-

IX.

Other

Question B: Based on your experience, prioritize the following online instructional supports from most (1) to least (6) helpful to families:

Internet solutions

Electronic devices

Digital literacy training and support for students

Digital literacy training and support for parents

Other support from counselors, social workers, librarians, or administration

Online content and applications

Question C: What differences did you observe between families who were more responsive versus those who were less responsive [during online instruction]?

By collecting qualitative data from the open-ended questions, the researchers intended to learn how teachers were engaging with their families via home-based learning. In order to get at potential answers, the researchers used the DI Framework as an exploratory lens for our coding and analysis.

Analysis

The survey analysis hones in on these questions above, which aim to identify teacher perceptions of family engagement and digital inclusion components based on their experience of online learning during the pandemic. None of the questions included the terms digital inclusion or family engagement but instead used other language familiar to educators (i.e. online instructional supports, family responsiveness, etc.).

The approach for analyzing differences in family engagement during online instruction [Question C] was guided by theoretical coding in which the survey responses were aggregated and coded into buckets based on keywords and ideas that teachers identified. After initial open coding, the data were analyzed using components of the DI Framework using the constant comparative method of data analysis, comparing one segment of data with another to determine similarities and differences (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016; Yin, 2014).

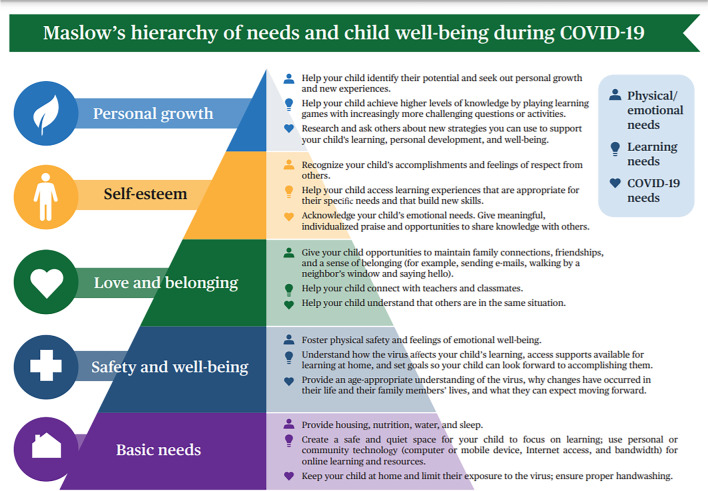

These initially coded responses were compared with the components and subcomponents of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943). The intent of utilizing this hierarchy was not only to understand whether digital inclusion fits in as an input of family engagement, but also the relationship between digital inclusion needs and other inputs of student achievement. We next compared the coded data with data from Question B, where teachers prioritized components of digital inclusion. This provided additional insight in understanding how to delineate components of digital inclusion within the hierarchy of needs framework. After the initial comparison of the coded data against the levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, we reanalyzed against an adapted hierarchy released by the Institute of Education Sciences that was informed by the Head Start Parent, Family, and Community Engagement Framework (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and Child Well-being During COVID-19

An alternative framework considered for the constant comparative method was the dual capacity building framework. However, this framework does not explicitly identify the role of basic needs, safety, and well-being into its framework, which was imperative due to strained socio-economic conditions of the pandemic and with many survey responses validating such. Ultimately recognizing the evolving nature of digital inclusion as new ICTs emerge, the constant comparative method enables a stronger understanding of the dynamic process and redefining of family engagement, student learning, and digital inclusion amidst a global pandemic.

Results

Based on the analysis above, the researchers grouped the results of the study into two broad categories: Parent supervision and support contributed to participation levels in online instruction, and teachers identified as more helpful those supports that addressed digital access rather than digital participation divides. These results are explained in more detail below.

Parent Supervision and Support

A majority of teacher respondents (n = 113) identified three factors that best explain differences in student engagement in online instruction: 1. Students’ motivation 2. Students’ lack of parent engagement and support 3. Students’ lack of parent supervision or childcare (see Table 1). These results demonstrate that a majority of teacher respondents recognized how parent engagement, support and supervision has affected students’ abilities to participate in online instruction and HBL. Additionally, all of the reasons indicated by teacher respondents in Question A provide a comprehensive understanding of where parent supervision, parent support, and digital access needs fit in relationship to other needs related to student engagement in online instruction.

Table 1.

Reasons for Differences in Student Engagement During Online Instruction

| Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs of Well-being During Covid-19 | Reasons for Differences in Student Engagement in Online Instruction | Count (n = 113) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal growth | Student motivation | 72 | 63.7% |

| Self-esteem | Lack of teacher interaction | 33 | 29.9% |

| Love and belonging | Student lack of parent engagement and support | 64 | 56.6% |

| Lack of classmate and peer interaction | 36 | 31.9% | |

| Safety and well-being | Student lack of parent supervision or childcare | 59 | 52.2% |

| Student internet access | 55 | 48.8% | |

| Basic needs | Student stress | 37 | 32.7% |

| Student access to technology | 36 | 31.9% |

Open-ended responses in Question C provided understanding of what effective parent engagement, support, and supervision looks like during the COVID-19 pandemic from the vantage of teachers. Teacher respondents identified different components such as a parent or caretaker’s ability to work or stay at home, their ability to understand and communicate in the predominant language (English), and their ability to use online tools such as a learning management system (LMS) to monitor a student’s daily schedule (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of families who were more responsive versus those who were less responsive

| Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs of Well-being During Covid-19 | Characteristics observed between families who were more responsive versus those who were less responsive | Count (n = 113) |

|---|---|---|

| Personal growth | Student Motivation | 2 |

| Student Learning | 11 | |

| Self-esteem | Student Achievement | 11 |

| Parent Involvement | 18 | |

| Love and belonging | Family Support | 4 |

| Parent Supervision | 9 | |

| Safety and well-being | Language | 4 |

| Digital Literacy | 6 | |

| Socioeconomic Status | 8 | |

| Basic needs | Health | 2 |

| Digital Access | 2 |

More Helpful Resources Addressed Digital Access Rather Than Digital Participation Divides

A majority of teacher respondents (n = 86) did not perceive resources for digital participation (online content & applications, digital literacy support for students and parents, and other support from school staff) to be as helpful as tools for digital access (electronic devices and internet) for families based on their experience. These averages and medians reflect teacher observations in terms of what has been helpful in their existing experiences. These helpfulness rankings of existing solutions suggest respondents perceive a greater level of quality with the current array of digital access resources compared to digital participation resources (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Rankings of the Helpfulness of Existing Digital Inclusion Solutions

| Digital Inclusion Component | Median | Average | Confidence Interval of Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Devices | 1 | 1.8 | 1.49—2.06 |

| Internet Solutions | 3 | 3.0 | 2.72—3.35 |

| Online Content & Applications | 4 | 3.6 | 3.26—3.95 |

| Digital Literacy Support for Students | 4 | 3.7 | 3.39—3.96 |

| Digital Literacy Support for Parents | 4 | 4.0 | 3.65—4.30 |

| Other Support from School Staff | 5 | 4.9 | 4.59—5.13 |

Discussion

For each of the characteristics of parent involvement with correlations with academic achievement in the 2018 meta-analysis, one or more components of digital inclusion align with each characteristic. Teacher respondents’ perceptions of the helpfulness of digital access resources compared with digital participation resources can be understood through Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow acknowledged that one level of needs does not have to be completely satisfied before addressing another. Rather, multiple levels of needs can be targeted at the same time. DI draws from the same philosophy of Maslow’s hierarchy, recognizing the value in not waiting to fully address digital access before addressing digital participation needs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Literature Review: Alignment Between Digital Inclusion and Effective Parent Involvement

| Components of Digital Inclusion | Parents Reading at Home | Parental Encouragement and Support for Leaning | Parents Holding High Academic Expectations/Aspirations | Communication Between Parents and Children Regarding School) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affordable, robust broadband internet service | The internet provides a gateway for parents to read millions of free books and other content to their child, who cannot afford or access physical books | Internet is a prerequisite for remote learning and online homework. Parents without home internet will not have the same opportunities to support their children in this learning | Internet is a prerequisite to access Learning Management Systems (LMSs) such as Canvas, Blackboard, or Google Classroom | Internet is a prerequisite for parents to access LMSs and receive emails from teachers and the school. Updates on student progress prompt communication regarding school between parents and children |

| Internet-enabled devices that meet the needs of the user | Parents access these books through a range of devices including smartphones, tablets, computers, and E-Readers | Parents with desktops or laptop access can adequately navigate and utilize all LMS functions, where some LMSs are not adequately formatted for mobile phones | Parents with basic phones can only receive calls or texts from the school. Parents with smartphones or other computer devices can receive additional communication via LMS, email, text, social media, or other tools | |

| Access to digital literacy training | Parents with adequate digital literacy training have a greater capacity to find and evaluate online books and content to read with children | Parents with internet and computer access are likely to have more leisure time to explore, practice, and gain digital literacy skills necessary to support their children’s learning. (Hollingworth et al., 2011) | Parents with tailored digital literacy training can navigate LMSs, including the many features and updates | Parents with adequate digital literacy training have a greater capacity to communicate with their child and teachers using these communication tools |

| Applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation, and collaboration | Many apps and online content available are designed to help parents read, practice, and learn with their children | LMSs are tools where parents can monitor and evaluate their child’s progress to hold them to high academic expectations | Phone calling systems, SMS software, and other tools provide translated messages to improve school and teacher communication with parents | |

| Quality technical support | Parents with the capacity to provide technical support can troubleshoot challenges related to their child’s homework or remote learning | |||

| Affordable, robust broadband internet service | “Internet connectivity matters…” | |||

| Internet-enabled devices that meet the needs of the user | “I have one guardian who doesn't know how to use tech and doesn't answer phone calls from anyone not in her phone. We have worked out a plan for the special ed teacher, and social worker to contact her with our issues.” | |||

| Access to digital literacy training | “Families that were more responsive understood the technology better and were able to access the materials needed to help their child learn and keep up with daily curriculum.” | “Parents that understood how to use online tools were more responsive. Older parents/ grandparents were not very responsive.” | ||

| Applications and online content designed to enable and encourage self-sufficiency, participation, and collaboration |

“Also, [more responsive parents] were likely to be following or observing my LMS.” “If my parents or caregiver could prompt students, it made a big difference. My students were much more attentive [during online instruction].” |

“Some parents don't check their email often.” “Willingness to begin an email exchange on email.” |

||

| Quality technical support |

Alignment between Digital Inclusion and Effective Parent Involvement*

*Based on Survey Question 3 that asks “What differences did you observe between families who were more responsive versus those who were less responsive [during online instruction]?”

While more teacher respondents identified that existing hardware and software solutions are more helpful than digital literacy support, this finding does not diminish the exigence of providing digital literacy support for students and adults. Rather, this finding suggests that teachers have had more experiences with helpful, robust resources for these solutions compared with digital literacy support. This can be explained in part because a larger market exists for digital access solutions than digital literacy training. With the increasing influence of the private sector in education and government, the predominant framing of the digital divide has been the digital access divide. With the digital access divide, data quantifying the disparities and metrics for defining success are more measurable than the digital participation divide. Resultantly, digital access has remained a more visible and urgent priority for funding during the pandemic without holistic consideration of digital literacy training and technical support.

Despite the predominant framing of the digital divide as an access divide, more studies have emphasized the role of digital literacy for equitable HBL (Wen et al., 2021). However, limited research studies describe how digital access and literacy moderate the role of family engagement in HBL. The findings from teacher respondents suggest that a parent or caretaker’s ability to both access and use online education tools assists their child in HBL. Responses identified that parents with digital literacy skills are better enabled to monitor student daily progress, as children spend more time on their devices for school. Conversely, the same parents with lower socioeconomic levels and English language proficiency are the more likely to rely on their children to broker technology and less likely to guide their children’s technology use (Katz et al., 2017). Ultimately, through gaining necessary digital literacy skills for online supervision, parents are able to utilize tools such as an LMS to hold their child to high academic expectations, start conversations with their child regarding assignments and grades, and provide encouragement and support for learning (Boonk et al., 2018).

Limitations

Results from the teacher surveys show patterns relating to family engagement that are useful for addressing the digital divide. That said, the above findings and discussion have significant limits that the authors acknowledge. We gathered our insights from an available population of teachers from whom we also collected data on other topics related to remote learning during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic at a time when we could not gather similar data from caregivers and students. Thus, our findings and discussion provide more “arm’s-length” insights about parent engagement via remote learning than we would prefer. In order to get a more robust picture of parent supervision, support, and resource use, we would need to find a way to ask similar questions of the families as we did of the teachers. Additionally, this study is an initial exploration. The findings and discussion presented here offer a window into the experiences of those teachers surveyed, and the authors do not claim that the insights presented broadly represent teachers’ perspectives on digital inclusion generally. More robust mixed-methods approaches taking in data from surveys, interviews, and observations of various stakeholders are needed in order to more clearly determine what different components of digital inclusion factor into family engagement in schools via home-based learning. With these limitations acknowledged, the authors nonetheless maintain that the findings and discussion presented here offer a starting point for further investigation.

Conclusion

“Schools are... the most direct local linkage to families and as the sites of parents’ primary motivations for adopting and learning how to use technologies” (Katz & Gonzalez, 2016). Schools have the unique ability to leverage parent motivations of supporting their children to systematically deliver digital literacy training and technical support in ways that libraries, nonprofits, and community and faith-based organizations cannot. Very few national or regional directives, policies, or statutory requirements exist to address parent DI needs alongside the students. The following considerations are necessary to ensure adequate alignment between DI and family engagement outcomes in schools:

Identify Existing and Threshold Digital Literacy Levels for Parents

Schools that engage in an asset-based approach (Kretzmann & Mcknight, 1993) can invite all key stakeholders (including parents, teachers, IT staff, social workers, curriculum specialists, and other staff) to identify local assets such as available time, skills, and growth areas where people are interested in learning more. This asset mapping process can support the development of specific outcomes for parents’ DI needs and a checklist of specific tools for parents to master to be successful in supervising and supporting their children’s education.

Strategically Integrate and Invest in Digital Inclusion for Parents

Schools have an opportunity to codify these DI outcomes for parents into institutional planning and vision documents such as family-school partnership action plans, education technology plans, or new plans dedicated towards addressing digital inclusion or equitable digital learning. This process can support both one-time and ongoing investments to ensure marginalized families have equitable opportunities to access and use ICTs to fully participate and support their child’s education.

Develop Ongoing Processes to Assess Emerging Needs

Schools can identify the appropriate “home” for addressing relevant digital inclusion outcomes. This home could be a department, cross-functional team, advisory group, or another body that could be responsible for ensuring outcomes are achieved and evaluated, as digital tools and skills that parents need evolve.

As long as ICTs evolve and socioeconomic gaps persist, marginalized communities will continue to experience digital divides. Ultimately, the framework of digital inclusion represents a system and investment schools can make to support the access and use of ICTs for families to ensure equitable opportunities for learning.

Acknowledgements

Parts of the research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, grant number R01DC012315. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michael Owens, Email: michael_owens@byu.edu.

Vikram Ravi, Email: vik.ravi15@gmail.com.

Eric Hunter, Email: ejhunter@msu.edu.

References

- Adams, E. A. (2016). Redefining family engagement for immigrant latino families (Order No. 10132165). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1837087454)

- Boonk L, Gijselaers HJM, Ritzen H, Brand-Gruwel S. A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review. 2018;24:10–30. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou, L., & Tucker, C. (2020). Social distancing, internet access and inequality. NBER. 10.3386/w26982

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

- Conradie, S. M. (2016). Home-based learning support groups in Western Australia: an interpretivist study (Doctoral dissertation, the University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia). Retrieved from https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/home-based-learning-supportgroups-in-western-australiaan-interp

- Correa, T. (2008). Literature review: Understanding the "second-level digital divide." Retrieved from. https://utexas.academia.edu/TeresaCorrea/. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Correa T. Bottom-up technology transmission within families: Exploring how youths influence their parents' digital media use with dyadic data. Journal of Communication. 2014;64(1):103–124. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall M, Fisher KE, editors. Digital inclusion: Measuring the impact of information and community technology. Medford, NJ: Information Today; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 4. Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships. The Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712. Retrieved from. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20405436. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Fan, X., & Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 1–22.

- Green, C. L., Walker, J. M., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (2007). Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 532.

- Hache, A., & Cullen, J. (2009). ICT and youth at risk: How ICT-driven initiatives can contribute to their socio-economic inclusion and how to measure it. JRC Scientific and Technical Reports. Retrieved from. https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC58427/jrc58427.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Hampton, P., Richardson, D., Brown, S., Goodhead, C., Montague, K., & Olivier, P. (2020). Usability testing of MySkinSelfie: a mobile phone application for skin self‐monitoring. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 45(1), 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hargittai, E. (2002). Second-level digital divide: Differences in people's online skills. Retrieved from. https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0109068 . Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Helsper E. The digital disconnect: The social causes and consequences of digital inequalities. Sage; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert M. The bad news is that the digital access divide is here to stay: Domestically installed bandwidths among 172 countries for 1986–2014. Telecommunications Policy. 2016;40(6):567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.telpol.2016.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Tyson DF. Parental involvement in middle school: A meta-analytic assessment of the strategies that promote achievement. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:740–763. doi: 10.1037/a0015362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth S, Mansaray A, Allen K, Rose A. Parents’ perspectives on technology and children’s learning in the home: Social class and the role of the habitus. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 2011;27:347–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00431.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz VS. How children of immigrants use media to connect their families to the community: The case of Latinos in South Los Angeles. Journal of Children and Media. 2010;4:298–315. doi: 10.1080/17482798.2010.486136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz VS, Gonzalez C. Toward meaningful connectivity: Using multilevel communication research to reframe digital inequality. Journal of Communication. 2016;66(2):236–249. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz VS, Moran MB, Gonzalez C. Connecting with technology in lower-income US families. New Media & Society. 2017;20(7):2509–2533. doi: 10.1177/1461444817726319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzmann, J.P. & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Retrieved from. https://resources.depaul.edu/abcd-institute/publications/Documents/GreenBookIntro%202018.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Jeynes WH. A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education. 2005;40:237–269. doi: 10.1177/0042085905274540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mapp, K., & Kuttner, P. (2013). Partners in education: A dual capacity building framework for education. Retrieved from. http://www2.ed.gov/documents/family-community/partners-education.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Marks, J., & Kominski, R. (1988). Statistical brief: From the current population survey. Retrieved from. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1988/demographics/sb-02-88.pdf. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Maslow A. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review. 1943;50(4):370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ. Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- National Digital Inclusion Alliance. (2017). Definitions.https://www.digitalinclusion.org/definitions. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Pierce J. Digital divide. The International Encyclopedia of Media Literacy. 2018 doi: 10.1002/9781118978238.ieml0052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, V. (2020). Digital equity: Equitable technology access and learning. [Unpublished manuscript.]

- Rhinesmith, C., & Kennedy, S. (2020). Growing healthy digital equity ecosystems during COVID-19 and beyond. Evanston, IL: Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. http://benton.org/digital-equity-ecosystems-report. Accessed 26 June 2022.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 3. The Free Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk J, Hacker K. The digital divide as a complex and dynamic phenomenon. The Information Society. 2003;19(4):315–326. doi: 10.1080/01972240309487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk J. Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings. Poetics. 2006;34(4–5):221–235. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Gwendoline CLQ, Lau SY. ICT-supported home-based learning in k-12: A systematic review of research and implementation. TechTrends. 2021;65:371–378. doi: 10.1007/s11528-020-00570-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin RK. Case study research design and methods. 5. Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]