Abstract

Background

Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU) is an environment associated with an important workload which is susceptible to lead to task interruption (TI), leading to task-switching or concurrent multitasking. The objective of the study was to determine the predictors of the reaction of the nurses facing TI and assess those who lead to an alteration of the initial task.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational study into the PACU of a university hospital during February 2017. Among 18 nurses, a selected one was observed each day, documenting for each TI the reaction of the nurse (task switching or concurrent multitasking), and the characteristics associated with the TI. We performed classification tree analyses using C5.0 algorithm in order to select the main predictors of the type of multitasking performed and the alteration of the initial task.

Results

We observed 1119 TI during 132 hours (8.5 TI/hour). The main reaction was concurrent multitasking (805 TI, 72%). The short duration of the task interruption (one minute or less) was the most important predictor leading to concurrent multitasking. Other predictors of response to TI were the identity of the task interrupter and the number of nurses present. Regarding the consequences of the task switching, long interruption (more than five minutes) was the most important predictor of the alteration of the initial task.

Conclusions

By analysing the predictors of the type of multitasking in front of TI, we propose a novel approach to understanding TI, offering new perspective for prevention strategies.

Keywords: Concurrent, Multitasking, Patient safety, Task interruption, Task switching

Introduction

Twenty years ago, the To err is human report lifted the veil off the medical error by pointing out that nearly 100,000 patients die every year from medical errors into the United States.1 This led to an awareness of the healthcare professional on their impact on patient safety, and opened a new opportunity for research to improve patient care. James Reason in Human error (1990) suggested that task interruption (TI) may induce lapses of attention and cause a specific type of error called omission. Interruption is a frequent event during everyday activities in healthcare.2 While operating rooms, intensive care units or emergency departments were studied as healthcare settings favouring task interruption, only one study evaluated task interruptions during patient handover in the PACU.3 Still, the PACU is an environment associated with an important cognitive load for the nurses considering rapid patient turnover, monitoring and alarms, drug administration, and multiple caregiver interactions as part of the workload. This environment is similar to that of an intensive care unit or emergency department both of which are propitious to task interruption.

The healthcare professional experiencing task interruptions reacts inexorably with multitasking. Pashler et al.4 defined two types of multitasking: the task switching, where the primary task switches to a new one, and the concurrent multitasking where both tasks are performed simultaneously. Those two processes rely on different neuronal pathways and induce different consequences.5 Multitasking is a frequent event. In more than 1000 hours of observation, Walter et al. estimated its incidence to be from 9 to 17 times per hour in an emergency department.6 Interruptions leading to multitasking are associated with an increase in error rate,7, 8 procedure failure, and clinical errors.9

Numerous studies focused on describing the characteristics of the interruptions and their consequences.10 Still, knowledge is lacking regarding the factors that may influence the type of response triggered by an interruption and its negative effect on interrupted task.

Our hypothesis is that task switching or concurrent multitasking may occur differently according to the characteristics of the interruption, like the task interrupted (related to patient care or not), the characteristics of the interrupter (colleague, patient), the duration of the interruption, and its context. We therefore prospectively studied tasks interruptions and multitasking during nurse activity in a university hospital PACU.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective observational study in the anesthetic department of a French university hospital in the PACU from the 8th of February to the 1st of March 2017. This paper was written according to the STROBE statement. The study has been submitted and approved by our local ethics board.

Setting

The PACU has a capacity of 12 patients for visceral, endocrinologic, urologic, and gynecologic procedures. During the daytime activity, from 8:10 AM to 8:00 PM, 4 nurses and 2 nursing assistants work in the PACU with a 30-minute lunch break. Each nurse is in charge of a maximum 4 patients. Day shifts are scheduled as follow: one nurse from 8:00 AM to 06:30 PM, two nurses from 9:00 AM to 07:30 PM and one from 11:40 to 07:30 PM. The 2 nursing assistants’ day shifts are 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM, and 12:30 to 8:00 PM.

Data collection

Each day for 16 days, a unique and different nurse pertaining to the PACU was observed. A rotation of four observers was organized with one per day observing one randomly selected nurse. The four observers were anesthetic nurse trainees. These trainees were former nurses with several years of experience in emergency care, intensive care, or in PACU. All the observers were trained to detect and characterize task interruptions. The information and consent of the observed nurse were obtained at the beginning of the day, and from the patient at the beginning of the procedure. There were no refusals to participate. Then, the observer took place in a corner of the room with a laptop and stayed there as discreetly as possible, with no direct contact with the observed nurse. The data was collected using an Excel spreadsheet designed for the study.

Variable

The investigator reported data using a standardized checklist adapted from an evaluation tool issued by the French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, HAS).

The definitions used for the task interruption, task switching, and concurrent multitasking are described in Table 1. The data collected for each interrupted task were:

-

-

The workload at the time of the task interruption characterized by the number of healthcare professionals present and the number of patients present;

-

-

The step of care of the initial task out of seven predefined steps of the PACU care process;

-

-

The caracteristics of the interruption: source, topic, duration defined as the time between the interruption of the initial task, and the end of the interrupting task;

-

-

Nature of the interrupter: Patient, Healthcare professional, or Non-human interruption. The Healthcare professional was stratified according to the hierarchy of the hospital as Authority: medical doctor, chief nurse, resident; Colleague: nurse or anesthetist nurse; Nurse assistant, or the interrupter could also be identified as the Nurse (self-interruption);

-

-

Type of multitasking: concurrent multitasking or task switching. In the case of task switching, the transfer of the task to another colleague or withholding of the initial task were documented;

-

-

The consequences of multitasking: resumption of the initial task or the alteration of the initial task. The alteration of the initial task was defined as the cancellation of the task or the delaying of the task (starting over, resuming lag, etc.).

Table 1.

Definition used for Task interruption, Task switching, and Concurrent multitasking.23

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Task interruption | Task interruption if defined by a break in performance, provisional or definitive, of human activity. The source of the task interruption is internal or external to the recipient. The task interruption causes a break in the workflow, a disturbance of the concentration of the operator, and an alteration of the performance of the act. The possible realization of secondary activities completes to thwart the smooth running of the initial activity. |

| Concurrent multitasking | Concurrent multitasking (or dual-task interference, dual-tasking, dual-task performance) is the performance of two or more actions simultaneously. |

| Task switching | Task switching is the management of multiple tasks in which there is switching between tasks that are progressing in parallel. |

The detailed data collected are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data collected for each interruption observed.

| Workload | Step of care | Interrupter | Interruption source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of healthcare professionals present | Patient admission | Oneself | Human direct interaction |

| Number of patient present | Drug preparation | Patient | Noise |

| Nursing care | Healthcare professional | Phone | |

| Patient record filling | Authority: Medical Doctor, Chief nurse, Anesthesiologist resident | Alarm | |

| Patient monitoring | Nurse/Anesthetist nurse | Other | |

| Patient set-up | Nurse assistant | ||

| Nurse shift | Other caregivers: SB, Regulator | ||

| Other: Non-human interruption |

| Subject of the task interruption | Duration of the interruption | Type of multitasking | Consequences of the multitasking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social interaction | < 1 min | Task switching | Resumption of the initial task with no alteration |

| Seek information | 1–5 min | Withholding of the initial task | Alteration of the initial task |

| Provide information | > 5 min | Transfer the task to another caregiver | Cancellation |

| Asking for help | Concurrent | Alteration | |

| Logistic | Start over | ||

| Other (Supervision, Reminder…) | Resumption lag | ||

| Other |

Objective

The primary objective of the study was to focus on the predictors of the reaction of the observed nurse (task switching or concurrent multitasking).

Our second objective was to select the predictors, in case of concurrent multitasking, leading to an alteration of the initial task.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were presented with their median associated with their interquartile range. Qualitative variables were presented using numbers and proportions. The homogeneity between classes was evaluated using Pearson’s Chi-square tests and Fisher Exact test (qualitative variable) and Welch t-test (quantitative variable).

In order to select and represent variables of importance for the description of the outcomes, classification tree analyses were computed using the C5.0 algorithm. The C5.0 algorithm is used to create a classification tree by selecting the most important variable for each node in order to lower the entropy among the different leafs created. Two classification trees were computed in order to explain (1) the choice of the nurse between concurrent multitasking or task switching, and in case of task switching (2), the resumption or alteration of the task. The predictor variables used for the analysis were the number of healthcare professionnals in the PACU, the number of patients in the PACU, the interrupter, the duration of the interruption, and the step of care.

Finally, in order to determined the stability of the first variable selected into the classification trees, we used 1000 bootstrap iteration to determined the percentage of selection of the first selected variable and confirmed his importance.

In all statistical tests (two-tailed), p-values smaller than 0.05 were considered as significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.4.3 (package C50 0.1.2).

Results

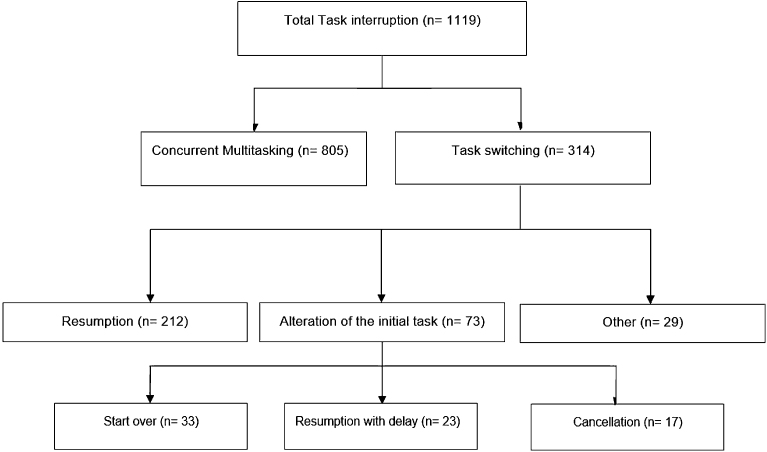

From the 8th of February to 1st of March 2017, we reported 1119 TI during 132 hours of observation (8.5 TI/hour), from 18 observed nurses. The main reaction was concurrent multitasking (805 TI, 72%). The task switching led to an alteration of the initial task in 73 TI (23%), with cancellation (17 TI, 23%), a resumption lag (23 TI, 32%), or starting over the task (33 TI, 45%). Among the 314 task switching, 291 result in witholding the initial task (93%), while 23 leaded to the transfer of the new task to another caregiver (8%). The repartition of the reaction and consequences of the TI are represented in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the reaction in front of a task interruption.

Table 3 describes the characteristics of the task switching and concurrent multitasking. Task switching was preformed preferentially when the interruption source was a direct human interaction or a noise, and among interrupters, self-interruption, or patient interruption led to task switching (Table 3). During the patient monitoring or the nurse shift, the task interruption resulted principally in task switching. Task switching was also the main reaction when the subject of the task interruption was logistic reason or asking for help.

Table 3.

Descriptive characteristics of the task switching and concurrent multitasking.

| Total | Task switching | Concurrent | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1119–100% | 314–28% | 805–72.0% | ||

| Number of patients during the interruption | 6 [5;7] | 6 [5;6] | 6 [5;7] | 0.211 |

| Number of healthcare professionals during the interruption | 6 [5;8] | 6 [5;8] | 6 [5;8] | 0.077 |

| Interruption source | < 0.001 | |||

| Human direct interaction | 964–86.1% | 233–74.2% | 731–90.8% | |

| Noise | 71–6.3% | 17–5.4% | 54–6.7% | |

| Phone | 38–3.4% | 30–9.6% | 8–1.0% | |

| Alarm | 25–2.2% | 17–5.4% | 8–1.0% | |

| Other | 21–1.9% | 17–5.4% | 4–0.5% | |

| Duration | < 0.001 | |||

| < 1 min | 931–83.2% | 201–64.0% | 730–90.7% | |

| 1–5 min | 152–13.6% | 91–29.0% | 61–7.6% | |

| > 5 min | 36–10.4% | 22–7.0% | 14–1.7% | |

| Interrupter | < 0.001 | |||

| Nurse | 392–35.0% | 79–25.2% | 313–38.9% | |

| Nurse anesthetist | 126–11.3% | 31–9.9% | 95–11.8% | |

| Authority | 98–8.8% | 34–10.8% | 64–8.0% | |

| Nurse assistant | 78–7.0% | 10–3.2% | 68–8.4% | |

| SB, Regulator, OC | 227–20.3% | 54–17.1% | 173–21.5% | |

| Oneself | 113–10.1% | 60–19.1% | 53–6.6% | |

| Other | 44–3.9% | 27–8.6% | 17–2.1% | |

| Patient | 41–3.7% | 19–6.1% | 22–2.7% | |

| Step of care | 0.002 | |||

| Patient admission | 82–7.3% | 18–5.7% | 64–8.0% | |

| Drug preparation | 65–5.8% | 15–4.8% | 50–6.2% | |

| Nursing care | 281–25.1% | 62–19.8% | 219–27.2% | |

| Patient record filling | 474–42.4% | 147–46.8% | 327–40.6% | |

| Patient monitoring | 99–8.8% | 40–12.7% | 59–7.3% | |

| Patient set-up | 68–6.1% | 14–4.5% | 54–6.7% | |

| Nurse shift | 50–4.5% | 18–5.7% | 32–4.0% | |

| Subject of the interruption | < 0.001 | |||

| Provide information | 208–18.6% | 52–16.6% | 156–19.4% | |

| Asking for help | 59–5.3% | 36–11.5% | 23–2.9% | |

| Seek information | 319–28.5% | 106–33.7% | 213–26.5% | |

| Social interaction | 131–11.7% | 24–7.6% | 107–13.3% | |

| Logistic | 85–7.6% | 48–15.3% | 37–4.6% | |

| Other | 317–28.3% | 48–15.3% | 269–33.3% | |

SB, stretcher bearer; OC, other caregiver.

Results are expressed in number of interruption and percentages for qualitative variable and median with their interquartile range for quantitative variable. p-value represents the p-value of a chi-squared test of the class between task switching and concurrent multitasking.

The practice of concurrent multitasking was predominant during the short interruptions (less than one minute), and when the task interrupter was a nurse assistant or another caregiver.

There was no difference in the mean number of patients in the PACU or of healthcare professionals for the two types of multitasking.

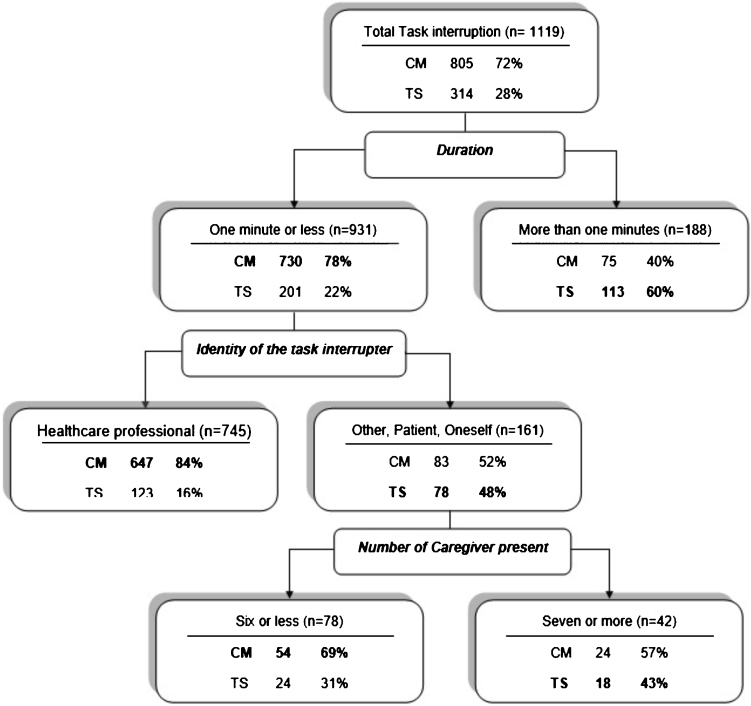

Considering the choice of task switching or concurrent multitasking, the most important associated factor was the duration of the task which interrupted the nurses. The short tasks (one minute or less) were significantly associated with the choice of concurrent multitasking, while longer tasks were associated with task switching. The other factors associated with the type of multitasking were the interrupter, the subject of the task interruption, and, less significantly, the number of nurses present (Fig. 2). Concerning the stability analysis, the duration was the most frequent variable selected (89.4%), followed by the identity of the task interrupter (9.8%).

Figure 2.

Classification Tree for the Task switching and Concurrent Multitasking. TS, task switching; CM, concurrent multitasking.

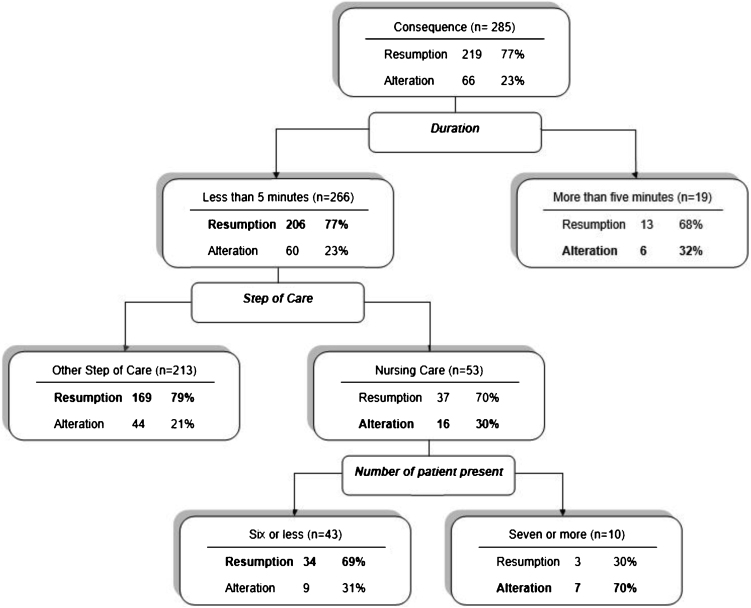

Regarding the consequence of the task switching on the initial task, we documented more alteration of tasks during longer periods of time (Table 4). While the duration was still the main characteristic to determine the resumption or the alteration of the initial task, the step of care and the number of patient present were the two other associated factors (Fig. 3). Concerning the stability analysis, the duration was the most frequent variable selected (75.7%), followed by the step of care (12.7%).

Table 4.

Descriptive characteristic of the consequence of the task switching on the interrupted task.

| Alteration | Resumption | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 73–24.6% | 212–74.4% | ||

| Number of patient during the interruption | 6 [5;6] | 6 [5;7] | 0.415 |

| Number of healthcare professionals during the interruption | 5 [4;6] | 5 [4;7] | 0.327 |

| Trigger | 0.790 | ||

| Human direct interaction | 57–78.0% | 157–74.0% | |

| Noise | 3–4.1% | 14–6.6% | |

| Phone | 5–6.9% | 22–10.4% | |

| Alarm | 3–4.1% | 9–4.3% | |

| Other | 5–6.9% | 10–4.7% | |

| Duration | < 0.001 | ||

| < 1 min | 37–50.7% | 145–68.4% | |

| 1–5 min | 23–31.5% | 61–28.8% | |

| > 5 min | 13–17.8% | 6–2.8% | |

| Interrupter | 0.114 | ||

| Nurse | 28–38.3% | 44–20.7% | |

| Nurse anesthetist | 5–6.9% | 24–11.3% | |

| Authority | 6–8.2% | 23–10.9% | |

| Nurse assistant | 2–2.7% | 7–3.3% | |

| SB, Regulator, OC | 13–17.8% | 36–17.0% | |

| Oneself | 8–11.0% | 47–22.2% | |

| Other | 7–9.6% | 18–8.5% | |

| Patient | 4–5.5% | 13–6.1% | |

| Step of care | 0.016 | ||

| Patient admission | 6–8.2% | 9–4.3% | |

| Drug preparation | 2–2.7% | 11–5.2% | |

| Nursing care | 21–28.8% | 37–17.6% | |

| Patient record filling | 30–41.1% | 106–50.0% | |

| Patient monitoring | 9–12.3% | 24–11.3% | |

| Patient set-up | 5–6.9% | 8–3.7% | |

| Nurse shift | 0–0% | 17–8.0% | |

| Subject of the interruption | 0.410 | ||

| Provide information | 16–21.9% | 35–16.5% | |

| Asking for help | 5–6.9% | 23–10.9% | |

| Seek informations | 25–34.2% | 71–33.5% | |

| Social interaction | 5–6.9% | 19–9.0% | |

| Logistic | 15–20.5% | 30–14.1% | |

| Other | 7–9.6% | 34–16.0% |

SB, stretcher bearer; OC, other caregiver.

Results are expressed in number of interruption and percentages for qualitative variable, and median with their interquartile range for quantitative variable. p-value represents the p-value of exact fisher test for the homogeneity of the class.

Figure 3.

Classification Tree for the consequence of the task switching (Alteration or Resumption).

Discussion

This study identified several important findings. First, to our knowledge, we conducted the first study to provide a description of a large number of task interruptions and its consequences in a PACU. Frequency of the TI is similar to those previously reported in ICU, emergency rooms and operating rooms.11, 12, 13 Second, it highlights the variety of reactions of the nurse facing a task interruption, and describes two possible outcomes (task switching and concurrent multitasking). These reactions are associated with factors that may negatively influence concurrent multitasking.

In this work, we confirm that concurrent multitasking is far more frequent than the task switching. This reaction occurs when the nurses face human interaction or when the interruption is a short-lived task (less than one minute). We suppose that the nurses are able to assess the duration of the interruption and evaluate the feasibility of their original task. The duration of interruption seems to be the major parameter of multitasking time, as a longer interruption leads to task switching.

The concurrent multitasking seems commonly preferred when a task is not complex and the duration of the interruption is short.6 Interestingly, it has been shown that the people who will most likely engage in concurrent multitasking have poor actual concurrent multitasking ability.14 Moreover, multitasking lowers IQ and productivity by 40%,15 decreases accuracy,16 and increases reaction time in response to environmental stimuli.17 The “Bottleneck effect” appears when cognitive capacities are overwhelmed by intense workload, a consequence of concurrent multitasking.18

We chose to study the consequences of the task switching on the initial task by dividing them as follows: either there is a resumption or an alteration of the initial task (starting over of the task, resumption with delay, or cancellation). When the nurses are interrupted in their task, we can observe a shift in attention from the initial process to the new one with a decay of the memory of the initial process. When the interrupting task is handled, the nurse moves back to the original task, but the step of the process when interrupted may be lost. Then, the interrupted nurse may start over the initial task, or even cancel it.10 Task switching activates an internal task set reconfiguration inducing an increase in response time to the new task and therefore the likelihood of errors.16, 19 Similarly, we found that the duration of the interruption was the major factor leading to the alteration of the initial task, and among the different steps of care, nursing care interruption was significantly associated to a higher rate of alteration of the initial task.

Moreover, the number of patients in the PACU is another significant factor associated to the alteration of the initial task, confirming that a higher workflow of patients probably favours the negative effect of the interruption.

The workload is a debated factor for the influence on the error rate. Weigl et al. investigated the impact of interruption and multitasking on patient care quality in an emergency department and reported that workflow interruptions were positively associated with patient-related information on discharge and overall quality of transfer.20 On the other hand, Westbrook et al. found no association between workload and error rate.7 In our study, there seems to be a negative (but modest) impact of the workload on the resumption of the initial task during task switching, leaving the discussion open for future research.

In a global approach regarding the flow of disruption and interruption in clinical practice, it is important to recall that the interruption and multitasking is not always harmful: not to mention the interruption in order to alert another healthcare professional of a safety problem, even the social interactions are also a necessity for human beings, and to provide a social environment improving communication.21

In our study, we did not compare the consequences of concurrent multitasking and task switching, and our design was not intended to extrapolate this conclusion. There are probably specific consequences for each multitasking choice. We chose to focus only on the consequences of task switching because of a simple, clear, and reproducible method. For logistical reason, we also did not choose the video recording tool to document the task interruption, which allows microanalysis of the footage and lead to a better investigation of adverse events.22 This allowed us to document a bigger number of interruptions, at the cost of using a simple classification and simpler analysis. In most categories, we successfully managed to classify each interruption, but regarding the subject of the interruption, we had 28% of the interruption classified as “other”. Furthermore, we did not study the impact of the personality or the intrinsic factor depending of the observed nurse, leading to potentially large unmeasured effect of observed nurse. The variability of the observed result related to the observed nurses need to be investigated in future study, as well as another classification for the subject of the interruptions might be used, more suitable to the PACU.

Conclusion

In this study, we selected the main predictor of the task switching and concurrent multitasking in order to improve our understanding in the health care setting. This encourages future research on flow disruption and multitasking, regarding the variability of the negative effect of each reaction (task switching or concurrent multitasking) caused by an interruption, the exploration of adapted prevention strategies, and confirm that the PACU is a suitable environment to document and investigate task interruption.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . National Academies Press (US); Washington (DC): 2000. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225182/ (accessed 27 Sep 2019) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reason J. Camb. Core; 1990. Human Error by James Reason. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rensen E.L.J., Groen E.S.T., Numan S.C., et al. Multitasking during patient handover in the recovery room. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:1183–1187. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31826996a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pashler H., Jolicœur P., Dell’Acqua R., et al. Control of cognitive processes: Attention and performance XVIII. The MIT Press; Cambridge, MA, US: 2000. Task switching and multitask performance; pp. 275–423. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deprez S., Vandenbulcke M., Peeters R., et al. The functional neuroanatomy of multitasking: combining dual tasking with a short term memory task. Neuropsychologia. 2013;51:2251–2260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter S.R., Li L., Dunsmuir W.T.M., et al. Managing competing demands through task-switching and multitasking: a multi-setting observational study of 200 clinicians over 1000 hours. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:231–241. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westbrook J.I., Raban M.Z., Walter S.R., et al. Task errors by emergency physicians are associated with interruptions, multitasking, fatigue and working memory capacity: a prospective, direct observation study. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2018;27:655–663. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn E.A., Barker K.N., Gibson J.T., et al. Impact of interruptions and distractions on dispensing errors in an ambulatory care pharmacy. Am J Health-Syst Pharm AJHP Off J Am Soc Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1319–1325. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.13.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westbrook J.I., Woods A., Rob M.I., et al. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:683–690. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera-Rodriguez A.J., Karsh B.-T. Interruptions and distractions in healthcare: review and reappraisal. BMJ Qual Saf. 2010;19:304–312. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.033282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg L.M., Källberg A.-S., Göransson K.E., et al. Interruptions in emergency department work: an observational and interview study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22:656–663. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell G., Arfanis K., Smith A.F. Distraction and interruption in anaesthetic practice. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:707–715. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drews F.A., Markewitz B.A., Stoddard G.J., et al. Interruptions and Delivery of Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Hum Factors. 2019;61:564–576. doi: 10.1177/0018720819838090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanbonmatsu D.M., Strayer D.L., Medeiros-Ward N., et al. Who Multi-Tasks and Why? Multi-Tasking Ability, Perceived Multi-Tasking Ability, Impulsivity, and Sensation Seeking. PLOS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell S.K. Mindfulness, Multitasking, and You. Prof Case Manag. 2016;21:61–62. doi: 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohrer D., Pashler H.E. Concurrent task effects on memory retrieval. Psychon Bull Rev. 2003;10:96–103. doi: 10.3758/bf03196472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijboer M., Taatgen N.A., Brands A., et al. Decision making in concurrent multitasking: do people adapt to task interference? PloS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borst J.P., Taatgen N.A., van Rijn H. The problem state: a cognitive bottleneck in multitasking. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2010;36:363–382. doi: 10.1037/a0018106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubinstein J.S., Meyer D.E., Evans J.E. Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2001;27:763–797. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigl M., Müller A., Holland S., et al. Work conditions, mental workload and patient care quality: a multisource study in the emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:499–508. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freischlag J.A. The operating room dance. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2012;21:1. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bezemer J., Cope A., Korkiakangas T., et al. Microanalysis of video from the operating room: an underused approach to patient safety research. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:583–587. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas H.E., Raban M.Z., Walter S.R., et al. Improving our understanding of multi-tasking in healthcare: Drawing together the cognitive psychology and healthcare literature. Appl Ergon. 2017;59:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]