Abstract

Background and objectives

Anesthesiologists and hospitals are increasingly confronted with costs associated with the complications of Peripheral Nerve Blocks (PNB) procedures. The objective of our study was to identify the incidence of the main adverse events associated with regional anesthesia, particularly during anesthetic PNB, and to evaluate the associated healthcare and social costs.

Methods

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we conducted a systematic search on EMBASE and PubMed with the following search strategy: (“regional anesthesia” OR “nerve block”) AND (“complications” OR “nerve lesion” OR “nerve damage” OR “nerve injury”). Studies on patients undergoing a regional anesthesia procedure other than spinal or epidural were included. Targeted data of the selected studies were extracted and further analyzed.

Results

Literature search revealed 487 articles, 21 of which met the criteria to be included in our analysis. Ten of them were included in the qualitative and 11 articles in the quantitative synthesis. The analysis of costs included data from four studies and 2,034 claims over 51,242 cases. The median claim consisted in 39,524 dollars in the United States and 22,750 pounds in the United Kingdom. The analysis of incidence included data from seven studies involving 424,169 patients with an overall estimated incidence of 137/10,000.

Conclusions

Despite limitations, we proposed a simple model of cost calculation. We found that, despite the relatively low incidence of adverse events following PNB, their associated costs were relevant and should be carefully considered by healthcare managers and decision makers.

Keywords: Complications, Costs, Nerve injury, Regional anesthesia, Complaints

Introduction

In the last decades, developed countries witnessed a significant increase in healthcare costs. At present, because of resources constraints, the financial sustainability of the health system has become of paramount importance. Such an increase in the relevance of economic criteria in decision-making processes, fosters the diffusion of economic assessments in the healthcare setting.1, 2, 3 Cost analyses provide decision-makers with relevant information about resource consumption and trade-off between costs and outcomes associated with different health technologies.4 The results of such analyses aim to reach rational approaches to introduce novel health technologies, particularly in rapidly evolving medical fields such as anesthesiology.4 In fact, anesthesiology is a medical field that has been characterized by relevant technologic advances, thus allowing safe pain management5, 6 and enabling the implementation of innovative cost-effective treatment approaches.7, 8, 9

Therefore, even relatively small risks related to the anesthetic technique might result in substantial negative consequences both for healthcare providers and for universal healthcare systems that are striving to contain costs. Care providers are always more often confronted with the challenge of fostering their reputation in contexts of regulated competition where care quality and patient satisfaction are paramount factors.

In the field of regional anesthesia, and specifically in the context Peripheral Nerve Blocks (PNB), the local anesthetic is injected in close proximity to a nerve or a nerve plexus to achieve an anesthetic or analgesic block. This approach reduces the adverse effects related to general anesthesia but it is not exempt from severe complications10, 11 as a consequence of the injection in the wrong tissue, organ, or cavity.12, 13 For instance, inadvertent intravascular injection of local anesthetics can cause acute neuro- and cardiac toxicity, eventually leading to cardiac arrest.14 Other complications might result from inadvertent intraneural injection and range from temporary to sustained or even permanent nerve damage. Minor nerve lesions may interfere with the patients’ professional life and are associated with medicolegal controversies that raise concerns for both healthcare professionals and hospital administrations. On the other hand, major lesions are associated with loss of limb function, dysesthesia, paresthesia, and chronic pain syndromes, significantly influencing the patients’ quality of life.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

The objective of our study was twofold. Firstly, we aimed at identifying and evaluating the incidence of the main adverse events associated with regional anesthesia, particularly during anesthetic PNB. Secondly, we evaluated the healthcare- and social associated costs of the aforementioned adverse events in order to assess their impact.

Methods

The present study was based on previously published studies and no ethical approval or informed consent were required.

Study identification and eligibility criteria

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA),23 we conducted a systematic search on the electronic databases EMBASE and PubMed. We specifically implemented the following search strategy: (“regional anesthesia” OR “nerve block”) AND (“complications” OR “nerve lesion” OR “nerve damage” OR “nerve injury”). We limited the search to the time lapse between January 1st, 2007 and June 1st, 2020 (included). Language restrictions were set to English, Italian, and Spanish. We also included gray literature (i.e., material such as reports and newsletters published by reputable anesthesiologists’ associations, fact sheets, etc.).

Two researchers independently filtered the retrieved results by reading titles and abstracts in order to identify publications on the topics of interest and apply specific eligibility and exclusion criteria. Eligibility criteria included randomized controlled trials, observational studies and reviews reporting on adult patients undergoing an operation intervention requiring regional anesthesia. We excluded studies that did not match the topic of interest, operations requiring neuraxial anesthesia (spinal or epidural anesthesia), sparse data regarding the outcomes of interest (incidence, costs, risk). Additional relevant studies were identified by snowballing the reference sections of the selected contributions and conducting manual search to include also pertinent, authoritative grey literature. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved by discussion.

Data collection, validation, and analysis

Following PRISMA guidelines and Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO)24 framework, the researchers independently extracted targeted data from the full-text versions of the selected studies. Relevant study characteristics including study type/design, sample size, primary anesthesia technique, incidence of injury, incidence of complications and adverse events were collected and further analyzed. Disagreements in data collection were discussed until consensus was reached. Ultimately, a third independent researcher verified the data extracted to solve discrepancies and check consistency. Data such as median reimbursement resulting from claims were extracted from each study and further analyzed.

Quantitative synthesis of the extracted data was performed through a pooled analysis in order to estimate the weighted average of nerve injury incidence according to the study sample size. In the occurrence of a lack of an explicit report of nerve injury incidence, it was calculated from percentage of the given total reported in the study.

Cost values comparability and measurement

When costs were expressed in different currencies and referred to different time periods, we adopted two standard approaches to make them comparable. We applied the trend of the Consumer Price Index to adjust monetary values (expressed in the preferred currency) coherently with the targeted period, while we applied the Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs, https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm) for the monetary values (expressed in the preferred time period) coherently with the target currency. Specific details were mentioned when applied to the actual values.

Since we adopted a societal perspective, we also considered the productivity losses associated with the PNB-related complications. In this respect, we applied the human capital approach and considered any initiative aimed to reduce PNB-related complications as an investment in a person’s human capital placing per-capita income (based on OECD data – see Table 1) as monetary weights on healthy years of life.25 Based on this monetary measure, we considered lifetime with disability as a productivity loss (up to 65-years age), regardless of the employment status, thus adopting a broad perspective of productivity as a measure of well-being (rather than strict economic welfare).26, 27, 28 We reported productivity changes separately so that one can easily decide on whether or not include them for specific evaluation purposes.

Table 1.

Estimates of variables involved in productivity losses estimation (2017).

| Context | Life expectancy at birth (years) | Annual income per capita (USD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| - a - | - b - | - c - | |

| Euro area | 82 | na | na |

| United Kingdom | 81 | 40,530 | 43,732 |

| United States of America | 79 | 58,270 | 60,558 |

USD, United States Dollars.

Sources: (a) The World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org), (b) WorldData.info (www.worlddata.info), (c) OECD (https://data.oecd.org).

Results

Literature search: included studies

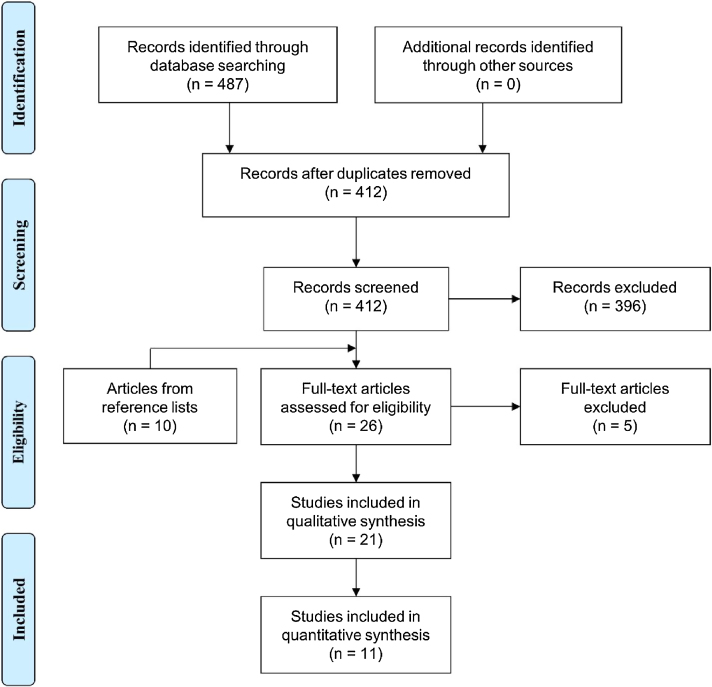

Literature search from EMBASE and PubMed revealed 487 articles. Seventy-five duplicates were identified, and 386 further articles were excluded since they did not match the main topic. Fifteen articles were evaluated in full-text and the manual references screening resulted in the retrieval of 10 additional articles. Five articles were excluded since they did not match the topic and a total of 21 was included (Fig. 1). Ten of them12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 only served the purpose of shaping the introduction and discussion of our work, and therefore were included in the qualitative synthesis. Eleven articles22, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 regarding incidence of PNB complications and claim costs were included in the quantitative synthesis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature search according to PRISMA Guidelines.

The analysis of incidence was based on data derived from seven studies. The majority of such studies were multicentric and prospective, with a sample size ranging from 143 to 158,083 cases. As far as costs were concerned, the analysis was based on data from four studies concerning legal claims. In fact, the sole economic analyses in the literature on this topic were based on secondary data from litigation databases of Authorities or Corporative associations. Therefore, all the analyses were retrospective and regarded Anglo-Saxon geographic contexts, with sample sizes ranging from 4,183 to 40,165 cases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Costs associated with Regional Anesthesia/Nerve injury.

| Author/s (year) | Context | Source | Data collection type | Period | Object of study | Sample size | Cost information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheney FW et al.29 (1999) | United States | ASA Closed Claim Project | Retrospective | 1990–1998 | Nerve damage by surgical or anesthesia instrument (perioperative nerve injury) | 670 (over 4,183) claims | All nerve injury median claim: USD 35,000 |

| Lee LA et al.30 (2008) | United States | ASA Closed Claim Project | Retrospective | 1980–2000 | Eye blocks and Peripheral nerve blocks (PNB) for surgical anesthesia claims | 218 (over 6,894) claims | PNB median claim: USD 58,800 |

| Eye block median claim: USD 126,900 | |||||||

| Cook TM et al.31 (2009) | United Kingdom | National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA) claims dataset | Retrospective | 1995–2007 | Financial impact of anesthesia-related claims | 841 (over 40,165) claims | Regional anesthesia median claim: £ 4,000 |

| Positioning median claim: £ 8,000 | |||||||

| Szypula K et al.22 (2010) | United Kingdom | National Health Service Litigation Authority (NHSLA) claims dataset | Retrospective | 1995–2007 | Financial impact of regional anesthesia-related claims | 366 (over 40,165) claims | CSE median claim: £ 82,000 |

| Eye median claim: £ 24,000 | |||||||

| Upper limb median claim: £ 500 | |||||||

| Lower limb median claim: £ 6,000 |

Costs are expressed in United States Dollar (USD) or United Kingdom Pounds (£).

Main adverse events associated with regional anesthesia

Among studies focusing on or including PNB, complications were not uniformly classified. In general, we noticed that the studies used a combination of clinical (e.g., seizure, nerve lesion) and overall health effects (e.g., peripheral neuropathy, abscess); sometimes the terms employed were rather generic (e.g., severe neurologic complications) or not strictly related to nerve injury (e.g., infection, pneumonia). This undermined our attempts of assessing the impact of complications in economic terms based on incidence data.

Incidence of the main adverse events associated with PNB

Overall, the incidence of peripheral nerve injury related to PNB performed in the perioperative setting ranged from 3.5 to 5.0/10,000 (Table 3); the mean value resulting from the pooled data was 4.0/10,000 cases. Whiting PS et al.38 and Capdevila X et al.35 reported significantly higher incidence values but these two studies, which focused on orthopedic surgery, included a wider range of complications than the other studies, thus not always allowing to identify complications specifically related to nerve injuries. In their systematic review, Kessler J et al.,15 with their analysis that included large studies such as Rohrbaugh M et al.39 and Sviggum HP et al.,21 reported a comparable incidence of complications after interscalene blockade in shoulder surgery.

Table 3.

Incidence of complications associated to peripheral nerve blocks.

| Author (year) | Period | Context | Multicenter | Study type | Sample size | Interventio/block type | Complications | Incidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auroy Y et al.32 (2002) | 1998–1999 | France | Yes | Prospective | 79,979 | Interscalene block (3,459) | Peripheral neuropathy | 2.9/10,000 |

| Supraclavicular block (1,899) | Seizures | 5.3/10,000 | ||||||

| Axillary plexus block (11,024) | Seizures | 0.9/10,000 | ||||||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1.8/10,000 | |||||||

| Midhumeral block (7,402) | Seizures | 1.4/10,000 | ||||||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 1.4/10,000 | |||||||

| 158,083 | Overall regional blocks | Severe neurologic complications | 0.35/10,000 | |||||

| Barrington MJ et al.33 (2009) | 2006–2008 | Australia | Yes | Prospective | 6,069 | Overall | Block-related nerve injury | 4/10,000 |

| Systemic local anesthetic toxicity | 9.8/10,000 | |||||||

| Belavic M et al.34 (2013) | 2012 | Croatia | No | Prospective | 143 | Overall | Block-related nerve injury | 5/10,000 |

| Capdevila X et al.35 (2005) | 2000 | France | Yes (8 university hospitals) | Prospective | 1'416 | Orthopedic surgery /Femoral | Nerve lesions | 44/10,000 |

| Abscess | 15/10,000 | |||||||

| Orthopedic surgery/Interscalene | Acute respiratory failure | 78/10,000 | ||||||

| Orthopedic surgery/Interscalene | Laryngeal and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis | 78/10,000 | ||||||

| Orthopedic surgery/PCB | Severe hypotension | 1,500/10,000 | ||||||

| Orthopedic surgery/Distal | Systemic local anesthetic toxicity | 263/10,000 | ||||||

| Orthopedic surgery/Axillary | Seizure | 79/10,000 | ||||||

| Huo T et al.36 (2016) | 2009–2011 | China | Yes (11 teaching hospitals) | Prospective | 106,596 | Overall | Major regional anesthesia complications | 3.47/10,000 |

| Orthopedics surgery (n = 31,097) | Horner syndrome (n = 5), Seizure (n = 1), Hematoma (n = 1) | 2.3/10,000 | ||||||

| Urology surgery (n = 16,769) | Seizure (n = 1), Paraplegia (n = 1) | 1.2/10,000 | ||||||

| General surgery (n = 17,907) | Horner syndrome (n = 4), Recurrent laryngeal nerve block (n = 5), Extensive neuraxial block (n = 5), Seizure (n = 3), Cauda equina syndrome (n = 1), Hematoma (n = 1), Cardiac arrest (n = 1) | 11.2/10,000 | ||||||

| Vascular surgery (n = 1,246) | Recurrent laryngeal nerve block (n = 1) | 8.0/10,000 | ||||||

| Plastic surgery (n = 1,579) | Extensive neuraxial block (n = 3) | 19/10,000 | ||||||

| Saied NN et al.37 (2017) | 2005–2011 | USA | Yes (300 community and academicals centers) | Retrospective | 64,119 | General surgery, vascular surgery, orthopedic surgery and genitourinary surgery | Peripheral nerve injury | 4/10,000 |

| Intraoperative c-reactive protein or death | 4/10,000 | |||||||

| Whiting PS et al.38 (2015) | 2005–2011 | USA, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Lebanon, United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates | Yes (462 hospitals in USA and 34 in the other countries) | Prospective | 7,764 | Hip fracture surgery (111 of PNB within the original ample) | Minor complications (wound dehiscence, superficial wound infection, pneumonia, and urinary tract infection) | 721/10,000 |

| Major complication (deep wound infection, organ space infection, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, cerebrovascular accident, postoperative neurological deficit, sepsis, septic shock, coma, and death within 30 postoperative days) | 810/10,000 | |||||||

| Overall complications | 126/10,000 |

PNB, Peripheral Nerve Blocks; USA, United States of America.

There were significant differences in terms of surgical interventions and the anesthetic technique applied. In addition, it is important to consider that the incidence varies according to: the proximity of the investigator’s look (the closer, the higher the rate of complications), the study design (retrospective vs. prospective) and the timing of the follow-up, as symptoms of nerve injury may not become clinically apparent before several weeks postoperatively.14, 17 These aspects were not evident, except for the distinction between retrospective and prospective studies.

Costs of adverse events associated with PNB

There were a few studies that quantified the economic impact of the complications associated with regional anesthesia and more specifically with PNB. The source of economic information regarding such topic were analyses of medico-legal claims related to anesthesia. These studies focused on two Anglo-Saxon geographic contexts: The United Kingdom and the United States of America (Table 2). According to the data extracted from these studies, the median reimbursement resulting from closed claims was rather different according to the Country involved. Lee et al.30 and Szypula et al.22 were the most similar in terms of the anesthetic technique applied. However, while Lee et al.30 referred specifically to payments associated with claims related to PNB, Szypula et al.22 referred to regional anesthesia.

Based on the data of the aforementioned two studies, the median cost of a claim associated with PNB ranged between 58,800 USD and 75,000 £ (95,045 USD) with the former value based on prices of 1999 and the latter based on prices of 2006. Using the trend of the Consumer Price Index in the time period between 1999 and 2006 (www.bls.gov/data/), the adjusted value of the US-based median was 85,350 USD; while using the Purchasing Power Parities, the UK-based value was 107,585 USD. We preferred to maintain the value adjusted to the year 2006 in order to avoid excessive correction errors and maintain a conservative approach in our evaluation. Despite being an objective type of information, it has two main limitations: (a) it tends to provide an evaluation perspective limited to the hospital; (b) even assuming that a claim closed in favor of a patient is a solid criterion to discriminate between a real complication associated with PNB and an economically irrelevant issue, this information does not include the costs connected to those who suffered a complication but did not issue a claim.

The first limitation could be overcome, for instance, by acquiring information about the health outcomes (or at least prognoses) associated with the reported incidence of complications. On the other hand, in the absence of such data, the pragmatic assumption that a claim payment includes the relevant social costs associated with a case of complications should be made in this way, the median cost of a claim becomes a satisfactory parameter in the single case in study. We could overcome the second limitation by projecting the median cost to the population of subjects that are likely to be affected by the complications taken into account in the study. The information on the incidence could be used to estimate this population, while the proportion of closed claims – that ranged from 51% and 53.5% according to Szypula K et al.22 and Lee et al.30 – was a candidate parameter to discriminate between relevant (i.e., block-related and economically significant) and irrelevant adverse events.

Therefore, knowing the volume of interventions adopting PNB (V), one could evaluate the costs of its complications by combining the following information:

| Evaluation of costs in USD = V * [0.035%; 0.05%] * 53% * [85,350; 107,585] = V * [15.8; 28.5] | (1) |

| Evaluation of costs in Euro = V * [0.035%; 0.05%] * 53% * [70,640; 89,040] = V * [13.1; 23.6] | (2) |

We assumed 53% as the proportion of relevant adverse events and the found range of incidence of adverse events associated with nerve injuries due to PNB (from 0.35% to 0.05%) when considering any type of intervention. As far as “V” is concerned, we could not find a reliable estimate. Therefore, we maintained it as a variable. More specifically, the first equation suggests that the “hidden costs” (i.e., associated with likely complications) for each PNB performed ranged between 15.8 and 28.5 USD.

If one considers that the strength of the previous pragmatic assumption (i.e., the hypothesis that a claim payment includes the relevant social costs associated with a PNB-related complication), an alternative approach consists of assessing productivity losses. In this respect, Lee et al.30 analyzed the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Closed Claims database in the period between 1990 and 2010 (overall 8,954 claims) and identified 189 patients who received PNBs in the setting of urgent surgery and with a mean age to 47 ± 14 years. They reported 31 claims related to nerve injuries (16.4%) resulting in permanent and/or disabling damage, while claims related to death (20) or brain damage (10) were the consequence of multiple damaging events, whose etiologies were sometimes difficult to ascertain or track. We could consider this information as a reliable basis to evaluate the productivity losses deriving from permanent disability associated with nerve lesions plausibly caused by PNBs. As further reported in the methods section, we could assume the Average Annual Income per capita (AAI) as a measure of the productivity loss for each year in which the subject could not work (due to the permanent disability) and the difference between the expected productive life (EPL, assuming that an individual is productive up to 65-years of age) and the average age of the sample of Lee et al.30 as a measure of the years lived.

| Evaluation of Productivity losses = V * [0.035%; 0.05%] * 53% * 16.4% * (EPL–AGE) * AAI = V * [0.003%; 0.004%] * (EPL–47) * AAI |

Based on recent estimates shown in Table 1, EPL could be considered equal to 65 (since life expectancy is above this threshold) and AAI considered the OECD value. For instance, in the USA the evaluation of productivity losses results was achieved through the following equation:

| Evaluation of Productivity losses (in USA) in USD = V * [0.003%; 0.004%] * (65–47) * 60,558 = V * [32.70; 43.60] | (3) |

This approach suggested that that the “hidden costs” (i.e., associated with likely complications) for each PNB performed ranged between 32.7 and 43.6 USD. If also the variability in terms of AGE (as reported by Lee et al.30 ±14 years) were included in the evaluation, the range broadened between 7.3 and 65.4 USD.

The two evaluation approaches described above suggested relevant costs associated with the phenomenon in study according to the different perspectives assumed. Although the aforementioned hidden costs may appear relatively low, the overall yearly expenditure could be significant for both the hospital and the community.

Discussion

In our systematic review, 21 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis and eleven of them were considered eligible to perform the quantitative synthesis. The pooled analysis of costs included data from 2,034 claims over 51,242 cases with a median claim of 39,524 USD. The overall estimated incidence of complications was 137 in 10,000 patients.

Nerve injury after regional anesthesia is regarded as a major complication and, when the damage is severe, may take weeks or even months to recover completely.12 One causative factor involves direct intraneural injection of local anesthetics. However, Bigeleisen P et al.13 challenged such concept by showing that intraneural injection is not invariably damaging. Nevertheless, if intraneural injection is not sufficient factor in the development of nerve injury, it is hard to challenge the idea that it is a serious risk factor, especially when the injection needle reaches the perineurium. Although several studies have been performed that analyze the etiology and physiology of this issue (together with techniques aiming at reducing its risk), the extant literature showed a paucity of contributions assessing the incidence of complications associated with regional anesthesia, particularly PNB.

It should be noted that the scientific literature on this topic seems to have thrived in recent years. This may be interpreted as an indicator of the growing interest in analyzing this topic from a quantitative perspective. The reported estimates showed a variability that is mainly linked to the type of intervention performed and study design, though there is a convergence toward a representative general value and, in general, reported data indicate a low rate of occurrence.

The fact that regional anesthesia has become routine practice for surgical procedures22 calls for more thorough analyses of the real costs. Basically, neurologic adverse events caused by PNB may affect patient satisfaction – and the hospital reputation – regardless of quality of the surgical procedure for which PNB was performed. Moreover, the more frequently PNB is performed, the higher the incidence also of infrequent events that may become relevant for both anesthesiologists and hospital managers.

We found that health outcomes associated with complications are reported in a heterogeneous way. Sometimes the authors report their clinical effects, while other authors refer to health outcomes; in fact, the terms used are frequently rather generic. This jeopardizes an effective comparison of the results among different studies and hampers a straightforward interpretation of the reported results, whose aim is to match economic and clinical information. In this respect, the economic assessment would greatly benefit from standardized reporting strategies based on health outcomes that can reliably be linked to complications with definite economic values. For instance, Sawyer RJ et al.19 proposed an interesting prognosis-based classification to assess the health outcomes of peripheral nerve injuries. However, data from the available incidence studies do not allow a correlation to such classification. The current scientific literature concerning the economic impact of complications associated with regional anesthesia (particularly PNB) is even poorer; in fact, the very few studies available are based on secondary data regarding legal claims in two Anglo-Saxon countries. Based on the available evidence, we tried to demonstrate that this phenomenon is not economically negligible, despite its relatively low rate of occurrence.

Limitations

Several authors have previously stressed the difficulty in estimating the incidence of adverse events associated with anesthesia because of the heterogeneity and quality of the literature on this topic.16, 18 Therefore, we are aware that – despite our focus on rigorous studies and the conservative hypotheses adopted – results must be interpreted with caution.

It is important to emphasize two major aspects regarding peripheral nerve complications caused by PNB. Firstly, they represent an infrequent phenomenon and therefore, its sampling is prone to error due to either the clustering phenomenon or its opposite (i.e., sampling interval without events).10 Secondly, the etiology of Perioperative Peripheral Nerve Injuries (PPNI) is complicated by several factors beyond the mere anesthetic injection (e.g., diseases affecting the microvasculature of nerves, poor perioperative positioning). Moreover, the clinical manifestations of PPNI may only become apparent before 48-h post-operatively and this may cast doubt on the cause of the injury.16

The four studies included reporting on claims did not explicit specify who was charged for the claims. However, one can assume that hospitals were primarily involved, but a characteristic of such costs is that they spread indirectly on healthcare systems and society in general. Therefore, we tried to address this limitation by assessing the socio-economic burden of PNB-related complications resulting in permanent and/or disabling injuries including productivity loss. We could not discern the level of disability, but the approach considers only one type of reported complication and results are likely to be conservative.

It is important to acknowledge that out of 11 studies, only 4 reported on costs and the remaining seven studies addressed nerve injury incidence. Thus, the present analysis used data from two sub-samples of studies for two different objectives. A further study limitation is the unfeasibility to generate an accurate risk of bias assessment and a plotted analysis; therefore, results should be considered merely descriptive. Moreover, an analysis of the risk of bias among studies and the publication bias would only play a marginal role, as evidence were not assessable.

Summary

Anesthesiologists and hospitals have nowadays to be confronted with the costs associated with complications belonging to misplaced injection of local anesthetics during PNB. We analyzed the extant literature in order to identify the main adverse events associated with PNB, in order to establish a reasonable estimate of their incidence and a model of the costs due to such complications.

Our results support the thesis that, although the rate of adverse events appeared to be relatively low, their associated costs were unneglectable, especially considering the large volume of PNBs performed and the growing role of anesthesiology in supporting innovative surgical techniques. Provided some limitations inherent to the data and based on some necessary hypotheses, we proposed a model of the costs associated with adverse events due to PNBs. From a strict hospital perspective, each PNB performed is associated with hidden costs ranging from approximately 18 to 23 USD (or 15 to 18 Euro). In terms of productivity losses, each PNB performed is associated with about 68 USD. Though the two evaluation approaches may overlap, they are also based on rather conservative hypotheses. Therefore, preliminary results show that such costs are relevant and should be carefully considered by healthcare managers and decision makers.

Despite the limitations of our study, we believe that our results help shed light on a matter that could prove profoundly relevant for healthcare systems which are striving to contain expenditures while at the same time trying to ensure universal access to healthcare.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study consider data already published, therefore, no institutional review board approval or consent to participate were required.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on request.

Funding

This article was financially supported by B. Braun Melsungen AG, Carl-Braun-Str. 1, 34212 Melsungen, Germany. The funding body supported the design of the study, the data collection and interpretation.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Rachele Contri, MD for English revision.

References

- 1.Siu A., Patel J., Prentice H.A., Cappuzzo J.M., Hashemi H., Mukherjee D. A cost analysis of regional versus general anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;39:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.05.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Regina D., Di Giuseppe M., Lucchelli M., et al. Financial impact of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:580–586. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mongelli F., Ferrario di Tor Vajana A., FitzGerald M., et al. Open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery: a cost analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29:608–613. doi: 10.1089/lap.2018.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ponsonnard S., Galy A., Cros J., Daragon A.M., Nathan N. Target-controlled inhalation anaesthesia: A cost-benefit analysis based on the cost per minute of anaesthesia by inhalation. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2017;36:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Argoff C.E. Recent management advances in acute postoperative pain. Pain Pract. 2014;14:477–487. doi: 10.1111/papr.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helen L., O’Donnell B.D., Moore E. Nerve localization techniques for peripheral nerve block and possible future directions. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59:962–974. doi: 10.1111/aas.12544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes M., Soares M.O., Dumville J.C., et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of general anaesthesia versus local anaesthesia for carotid surgery (GALA Trial) Br J Surg. 2010;97:1218–1225. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saporito A., Calciolari S., Ortiz L.G., Anselmi L., Borgeat A., Aguirre J. A cost analysis of orthopedic foot surgery: can outpatient continuous regional analgesia provide the same standard of care for postoperative pain control at home without shifting costs? Eur J Health Econ. 2016;17:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s10198-015-0738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borendal Wodlin N., Nilsson L., Carlsson P., Kjølhede P. Cost-effectiveness of general anesthesia vs spinal anesthesia in fast-track abdominal benign hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.043. 326.e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent C.D., Bollag L. Neurological adverse events following regional anesthesia administration. Local Reg Anesth. 2010;3:115–123. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S8177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg A.P., Rosenquist R.W. Complications of peripheral nerve blocks. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2007;11:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgeat A. Regional anesthesia, intraneural injection, and nerve injury. Beyond the epineurium. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:647–648. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigeleisen P. Nerve puncture and apparent intraneural injection during ultrasound-guided axillary block do not invariably result in neurologic injury. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:779–783. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liguori G.A. Complications of regional anesthesia. Nerve injury and peripheral nerve blockade. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2004;16:84–86. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200401000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler J., Marhofer P., Hopkins P.M., Hollmann M.W. Peripheral regional anesthesia and outcome: lessons learned from the last 10 years. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:728–745. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalkhen A.G., Bathia K. Perioperative peripheral nerve injuries. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2012;12:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marhofer P., Fritsch G. Safe performance of peripheral regional anaesthesia: the significance of ultrasound guidance. Anaesthesia. 2017;72:431–434. doi: 10.1111/anae.13831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pathak L. Peri-operative peripheral nerve injury. Health Renaissance. 2013;11:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer R.J., Richmond M.N., Hickey J.D., Jarrratt J.A. Peripheral nerve injuries associated with anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:980–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shetty T., Nguyen J.T., Wu A., et al. Risk factors for nerve injury after total hip arthroplasty: a case-control study. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sviggum H.P., Jacob A.K., Mantilla C.B., Schroeder D.R., Sperling J.W., Hebl J.R. Perioperative nerve injury after total shoulder arthroplasty: assessment of risk after regional anaesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2012;37:490–494. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31825c258b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szypula K., Ashpole K.J., Bogod D., et al. Litigation related to regional anaesthesia: an analysis of claims against the NHS in England 1995-2007. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schardt C., Adams M.B., Owens T., Keitz S., Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond M.F., Sculpher M.J., Claxton K., Stoddart G.L., Torrance G.W. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2015. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckert K.A., Carter M.J., Lansingh V.C., et al. A simple method for estimating the economic cost of productivity loss due to blindness and moderate to severe visual impairment. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:349–355. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1066394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frick K.D., Joy S.M., Wilson D.A., Naidoo K.S., Holden B.A. The global burden of potential productivity loss from uncorrected presbyopia. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1706–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Łyszczarz B., Nojszewska E. Productivity losses and public finance burden attributable to breast cancer in Poland, 2010-2014. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:676. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3669-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheney F.W., Domino K.B., Caplan R.A., Posner K.L. Nerve injury associated with Anesthesia. J Anesthesiol. 1999;90:1062–1069. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199904000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee L.A., Posner K.L., Cheney F.W., Caplan R.A., Domino K.B. Complications associated with eye blocks and peripheral nerve blocks: an american society of anesthesiologists closed claims analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook T.M., Counsell D., Wildsmith J.A.W. Litigation related to anaesthesia: An analysis of claims against the NHS in England 1995-2007. Anesthesia. 2009;64:706–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auroy Y., Benhamou D., Bargues L. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS regional anesthesia hotline service. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1274–1280. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barrington M.J., Watts S.A., Gledhill S. Preliminary results of the australasian regional anaesthesia collaboration. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:534–541. doi: 10.1097/aap.0b013e3181ae72e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belavic M., Loncaric-Katusin M., Zunic J. Reducing the incidence of adverse events in anesthesia practice. Periodicum Biologorum. 2013;115:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capdevila X., Pirat P., Bringuier S., et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:1035–1045. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200511000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huo T., Sun L., Min S., et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in 11 teaching hospitals of China: a prospective survey of 106,569 cases. J Clin Anesth. 2016;31:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saied N.N., Helwani M.A., Weavind L.M., Shi Y., Shotwell M.S., Pandharipande P.P. Effect of anaesthesia type on postoperative mortality and morbidities: a matched analysis of the NSQIP database. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118:105–111. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiting P.S., Molina C.S., Greenberg S.E., Thakore R.V., Obremskey W.T., Sethi M. Regional anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery is associated with significantly more peri-operative complications compared with general anaesthesia. Int Orthop. 2015;39:1321–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2735-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rohrbaugh M., Kentor M.L., Orebaugh S.L., Williams B. Outcomes of shoulder surgery in the sitting position with interscalene nerve block: a single-center series. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:28–33. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318277a2eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on request.