Abstract

In children's chronic pain services, healthcare decisions involve a three‐way interaction between the child, their parent or guardian, and the health professional. Parents have unique needs, and it is unknown how they visualize their child's recovery and which outcomes they perceive to be an indication of their child's progress. This qualitative study explored the outcomes parents considered important, when their child was undergoing treatment for chronic pain. A purposive sample of twenty‐one parents of children receiving treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain, completed a one‐off semi‐structured interview that involved drawing a timeline of their child's treatment. The interview and timeline content were analyzed using thematic analysis. Four themes are evident at different points of the child's treatment course. The “perfect storm” that described their child's pain starting, “fighting in the dark” was a stage when parents focused on finding a service or health professional that could solve their child's pain. The third stage, “drawing a line under it,” changed the outcomes parents considered important, parents changed how they approached their child's pain and worked alongside professionals, focusing on their child's happiness and engagement with life. They watched their child make positive change and moved toward the final theme “free.” The outcomes parents considered important changed over their child's treatment course. The shift described by parents during treatment appeared pivotal to the recovery of young people, demonstrating the importance of the role of parents within chronic pain treatment.

Keywords: child, chronic pain, outcome, parent, qualitative

1. INTRODUCTION

Adults experiencing chronic pain can seek a diagnosis and treatment for themselves and choose to decline or accept any treatment that has been suggested. Conversely, children are taken to hospital appointments by their parents or guardians. Healthcare decisions are shared in a three‐way interaction between parents, children, and health professionals. 1 , 2 Treatment recommendations such as practicing psychological or physical interventions, involve parents arranging family life to facilitate, remind, supervise, or assist their child. These key differences mean that the perspectives of parents, alongside their children, are integral to the management of chronic pain in children. 3 , 4 Rather than applying adult evidence or simplifying adult outcome measures to pediatric populations, there is a drive to make children's pain visible using assessments that hold relevance to the child and their family. 4

Parents have their own unique needs in response to caring for their child experiencing chronic pain. 5 Qualitative studies involving parents of children treated for chronic pain describe an initial disempowerment in parenting 5 , 6 , 7 followed by a re‐evaluation or empowerment. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Parents have also highlighted the importance of finding a diagnosis for their child 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 and developing a positive relationship with health professionals. 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 These qualitative findings are not reflected in the core outcome domains recommended for clinical trials in pediatrics. 12 , 13 In the core outcome set updated and published in 2021, the group (involving parents, young people, and health professionals), voted to exclude treatment satisfaction, 13 and parental functioning has not been an outcome domain identified as important. 12 , 13 , 14 There are, however, a large number of measures available to measure parental functioning that are used without consistency across pediatric chronic pain studies. 15

Clinically, it is important to measure outcomes during a patient's treatment, as health professionals can establish progress or deterioration, allowing treatment to be tailored. This is also an important stage in validating patient and family experience. While the end result is often the focus in clinical trials, in clinical practice establishing an endpoint of treatment is ambiguous, often without the end being predefined. Contrary to the core outcome set for research trials, guidelines on the clinical management of chronic pain do not expand beyond recommending a biopsychosocial assessment. 3 Although it has been important to achieve consensus in opinion regarding what outcome domains to measure in research trials, it is also important to understand the range of outcomes that parents may consider important, and whether these preferences change, depending on the stage of treatment. Therefore, this study aimed to (1) establish which outcomes parents considered important to measure during their child's treatment for chronic pain and why; and (2) discover whether these preferences changed during the course of treatment. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) was completed 16 to optimize reporting.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This qualitative cross‐sectional study was part of a larger program of research that used novel methods informed by Q‐methodology, and public, patient involvement and engagement to answer the research question: “Which outcomes do young people and their parents consider the most important to measure during the treatment of chronic pain?.” This paper reports a subset of the data, reporting the opinion of parents through single semi‐structured interviews. As part of the interview, parents were invited to draw a timeline of the trajectory of their child's pain treatment. 17 This enabled outcomes to be explored over time, along with the endpoint of treatment (when their child no longer required hospital treatment). The same study design was used to gain the opinions of young people during the same time period (May 2018–April 2019) and full details including the interview schedule, have been published separately. 18 Multiple media were offered (face‐to‐face at home or in hospital, telephone, online video, or online messenger) and the interview schedule was co‐designed and tested with two young people and a parent from the target population. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Service (NHS, Leeds, UK) Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 18/SC/0138).

2.2. Participants and recruitment

Participants were a purposive sample of parents who had children aged 11‐18 years being treated for chronic musculoskeletal pain. This was defined as pain located in muscle, joints, or soft tissue; that had existed for more than 3 months; and where systemic disease (for example, juvenile idiopathic arthritis) had been excluded. Parents of children with long‐term comorbidities resulting in permanent disability, and parents unable to communicate in English without assistance were excluded.

Participants were recruited from local and tertiary services (i.e., physiotherapy departments, rheumatology clinics, child psychology services, and multidisciplinary chronic pain clinics) within two hospital sites in England. After clinical staff initially mailed all eligible parents, parents were purposively sampled to represent parents of children based on age, gender, and treatment stage. The researcher visited the hospital sites monthly, updated clinical staff on gaps in recruitment and attended clinics (researcher available in a separate room to discuss the research). All parents received the study information for over 48 h prior to providing their express written consent to participate and did not receive any remuneration fee for their time. Consent forms were completed in person if the interview was completed face‐to‐face and if parents chose to be interviewed online or via the telephone, they emailed or messaged the researcher a photograph of the completed consent form prior to the interview starting.

2.3. Data collection

Where possible, parents were given the opportunity to talk without the presence of their child or spouse. The lead author interviewed all participants and was introduced as a researcher. She was undertaking the research while concurrently working as a specialist physiotherapist within a pediatric chronic pain team at different hospital site and was not involved in any of the participants' treatment. Immediately following the interviews, the researcher completed field notes detailing nonverbal behaviors, observations, and reflections. All interviews were audio‐recorded using a digital voice recorder and transcribed verbatim. Participants kept their timelines, and a photograph copy was used for analysis. The transcripts were not returned to participants as the timeline served as written summary of what was discussed, and parents could amend this as they wished throughout the interview. Verbal and written accounts offered some degree of data triangulation. Pseudonyms were used and any information that could potentially identify participants was removed.

2.4. Data analysis

The words written on the timelines and interview transcripts were coded using thematic analysis. This inductive approach enabled important outcomes to be derived without the use of a priori framework. The analysis took place alongside the data collection and the timeline was analyzed first to give the initial codes a sequence over time which was less apparent in the interview. Codes were collected and displayed along a single timeline in paper format without the use of software. Coding and analysis followed the six stages of thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke 19 : (1) familiarizing yourself with your data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes and; (6) producing the report. Coding and the generation of themes were completed by all three authors, L.R and M.D.‐H. are experienced in analyzing qualitative data and supervised R.J. The team provided triangulation of expertise across pediatric and adult health and psychology. To increase dependability, the initial codes, map of themes and all team meetings were documented to offer an audit trail of how the codes were established and how the data and themes were revisited until finalized. Credibility was increased by reflexivity: the main author shared their field notes and personal reflections of the interviews with the team, and during the development of initial codes and themes, reflections were recorded. During the analysis of the final three interviews, no new initial codes were identified, and all three authors considered a point was reached where further interviews were unlikely to change the overall story.

2.5. Results

Twenty‐one parents took part, nine of whom had been met in clinic by the researcher at the time of recruitment. Twelve parents were recruited from a tertiary service and nine were recruited from a local service (including physiotherapy (n = 7) and psychology (n = 2)). Three couples (a mother and father from the same family) took part, two couples were interviewed together due to time pressures on family life. One mother was interviewed with their child present and the remaining 17 parents were interviewed separately. The average length of interview was 57 min (range 28–84 min). Thirteen parents chose to be interviewed face to face at home (62%), six chose to talk via the telephone (28%), one chose a video call (5%), and one chose to talk face to face in the hospital (5%). Table 1 shows the parent and child demographic information.

TABLE 1.

Demographic information of the participants (n = 21).

| Characteristic | Results |

|---|---|

| Gender of parent, n (%) | |

| Female | 17 (81%) |

| Male | 4 (19%) |

| Gender of their child, n (%) | |

| Female | 16 (76%) |

| Male | 5 (24%) |

| Age of their child in years and months | |

| Mean (range) | 14. 9 (11.4–18.0) |

| Child's initial pain location, n (%) a | |

| Lower limb | 8 (38%) |

| Multiple joints | 7 (33%) |

| Chest, back | 5 (24%) |

| Upper limb | 1 (5%) |

| Duration of their child's pain in months a | |

| Mean (range) | 46 (5–120) |

| Treatment setting a | |

| Only outpatient treatment | 16 (76%) |

| Involved inpatient rehabilitation | 5 (24%) |

| Diagnosis of their child a | |

| Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) | 6 (29%) |

| Chronic Primary Pain | 6 (29%) |

| Unknown/no diagnosis | 5 (24%) |

| Hypermobility syndrome/Hypermobile Ehlers Danlos Syndrome | 3 (14%) |

| Orthopedic diagnosis e.g., costochondritis | 1 (4%) |

Based on parent report.

In the thematic analysis, four themes were identified: “the perfect storm”; “fighting in the dark”; “drawing a line under it” and “free.” These themes occurred at different stages of treatment and are discussed in the order they presented. Parent quotes using pseudonyms and the words used by parents (in italic and speech marks) illustrate each theme.

2.6. Theme 1: “The perfect storm”

This theme occurred at the beginning of children's treatment and as shown in Figure 1, it describes three stages. The first stage describes the observations parents made in the build‐up prior to their child's pain with multiple factors combining that were akin to a storm building. This was followed by the pain starting like an unpredictable and forceful storm that led to the final stage, their child experiencing loss. As deduced from the data, in this stage parents focused on the outcome domains of their child's pain intensity and pain interference with everyday life.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the theme “perfect storm.”

Parents most often described other health problems experienced by their child in the build‐up to the pain starting. These were previously diagnosed or were under investigation and acknowledged at the same time as the onset of their child's pain.

He was also getting flashing lights, headache, so he ended up having an MRI which I think, there was nothing there, but um it was a just a combination of it all and nothing we could pin down…and upset tummy…[they] attributed joint hypermobility. (Jemima)

A group of parents spoke of their own, spouse's or siblings' health diagnoses and most of these parents made connections to the onset or nature of their child's symptoms or discussed the additional burden these diagnoses had on their child. A further smaller group of parents were perplexed by their child's recurrent injuries from “very innocuous” events. Some parents acknowledged the influence of puberty and changes in their child's friendships in this build‐up stage.

At one point there was [sic] a few things going on at school. There was a bit of stress…that was when the hormone was all kicking in as well and getting particularly bad. (Sarah)

When the pain started, the majority of parents discussed their child vocalizing pain. This included their child “complaining” and displaying behaviors such as crying, huffing, screaming or “moaning.” Parents described the frequency and length in which their child would verbalize pain and described how this behavior felt “very absorbing.”

Waking everyday with ‘my head, my head’ (Rachel)

One of the parents, introduced a theory that verbalizing pain might be an unconscious way that young people can get their parents attention, the reason why they need their attention may be unknown to the young person, yet they may not be able to articulate their need in any other way.

Parents then described loss as a consequence of the pain. Their child being isolated socially was the most frequently described loss because of the pain starting. Parents then described their child's physical loss (for example not being able to walk) and the loss of their child's health (their child being “ill”). The most common expression used by parents at this stage was “frustration.” They did not understand why their child was experiencing this level of pain, struggled to juggle family life with hospital appointments and felt there was a general lack of understanding by health professionals. They described watching their child “slowly disappearing” changing from being “bubbly,” “happy,” “quirky,” “silly,” and “vibrant” to “depressed,” “upset,” “withdrawn,” “grumpy,” and “worried.”

Most parents attributed these negative changes to their child's demeanor and social interactions as a result of the physical restrictions of pain. Not being able to play sport or being segregated at school (because they were using crutches) meant they were no longer part of conversations or events.

So she spent a lot of time in her room…wasn't really socializing and I think just miserable because she was on crutches, you know, I don't think it was easy for her. (Amanda)

In contrast, a smaller group of parents described how their child “withdrew” from their friends and “reclused,” attributing this to them feeling misunderstood and disbelieved by their peers. A couple of parents also described how there appeared to be a difference in the perception of their child's pain in school and at home. For example, although these parents explained how their child's physical capabilities had deteriorated at home, when health professionals contacted the school, staff reported that there had been no changes.

We just couldn't believe it…at home [name] was this disabled person. (Kimberly)

2.7. Theme 2: “Fighting in the dark”

This theme describes parents doing whatever they could to find a solution for their child's pain. During this stage, parents placed importance on the outcome domain of treatment satisfaction and experience. All parents described this stage and three parents specifically used the word “fighting” to describe how they interacted with health systems and health professionals to access services and treatment. The words “in the dark” were used to describe how parents felt helpless, not knowing why their child had pain and as a consequence were “grabbing at all sorts.” Just under half the parents remained in this stage at the time they were interviewed.

Figure 2 summarizes the theme and demonstrates how three factors: their child's pain worsening, negative healthcare experiences and lack of parental support, increased the amount a parent felt they had to fight, to protect and advocate for their child. These three different components are now discussed in more detail.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the theme “fighting in the dark.”

To gain access to services, parents reported “jumping through hoops” and having to “push” for the “right” person to see their child. At the very least, parents perceived that “going back constantly” to the doctor and attending appointments felt like they were doing something for their child.

You've always got someone to keep the narrative going. That doesn't change anything physically…I just think it makes us feel like we're not just sitting on our hands, doing nothing. (Christopher)

Conflict arose when a medical cause could not be found and rather than feeling reassured, parents felt “dismissed.” This could also cause conflict within families where a spouse felt the other parent was not being forceful enough.

[My wife] and her family especially were saying, you're rubbish, you're not getting any results from this, somebody else needs to take her because you're too easily fobbed off …it becomes my fault. (Michael)

When a chronic pain diagnosis was given to parents, a large group described the negative consequences of this event.

I've got that date stuck in my head…because it crushed me [crying]…He didn't tell me anything about the condition just said it was CRPS… I went home and did read up on what CRPS was because you would…it scared the hell out of me. (Elizabeth)

The implication of a psychological component presented to parents at any point in their child's treatment was a reason parents increased their “fight” with health professionals. Many parents felt the mention of anxiety, low mood, or the involvement of the brain, meant the health professional was implying their child's pain was not real. The words and language used were important.

She saw a psychiatrist…who said to me about ‘unexplained pain’ and almost as if there was this psychological element to it and I went back to the paediatrician and said I'm a bit confused because you're saying that it is a physical condition and he's hinting it's psychological and the paediatrician said, ‘I think it's a case of semantics’ and I thought no it's not. (Amanda)

One parent sensed the unease of healthcare professionals when delivering the diagnosis and described how they would fall back to physical explanations, and psychological aspects became a “secret thing” they kept to themselves due to a “cacophony of no‐one really knowing what to tell the patient.” However, preexisting beliefs about psychology differed among parents and among couples.

[My child] might need to have some psychology… [my wife] was saying ‘probably not’, I was trying to get the middle ground. (Matthew)

Another source of conflict was when their child's treatment did not meet their expectations, made their child's symptoms worse, or parents felt side‐lined or even blamed. One parent describes being referred to social services several times as her child's problems were considered a result of “bad parenting.”

The quotes from parents who described their child's deterioration after intensive treatment in hospital were the most harrowing. They described the worsening of their child physically and emotionally. A mother described how her child walked into hospital but left in a wheelchair. The parent quotes portrayed a loss of hope in their child's recovery.

You can't just say ‘there's your daughter she's a bit more broken but have her back we can't do anything with you’. That's how it felt. (Ashley)

Parents also described how their child's hospital admission had significantly impacted them.

It [child's leg] was purple, she wanted it cut off, she was psychologically really damaged…If I'm honest that 5‐weeks was the worst 5‐weeks of my life. (Melissa)

Interestingly, there were three cases where parents observed their child make improvement, two following a holiday and one after starting part‐time employment. This improvement transiently stopped parents “fighting” however, when symptoms returned or changed, parents fought for new answers from healthcare professionals and services.

Looking for their own support was something parents rarely did. They did not want to burden others with their problems or feel judged. Parents discussed the differing opinions of their spouse, grandparents and siblings that ultimately meant they felt alone.

She [parent's mother] turns round and says, ‘oh there's nothing wrong with him, you're just putting it on.’ (Heather)

This differing opinion could lead to conflict within the family or led to one parent making decisions such as their child having time off school due to pain, without the support of their spouse.

Her dad will always say things [to child] like…‘oh when you're at work, you can't have time off or they'll sack you’ …I'm like ‘this isn't helping’ (Danielle)

In addition to a lack of support at home, parents described unsupportive healthcare professionals and being alone on their pursuit for help.

I feel like I'm hitting a brick wall with the ‘let's make this better’. And I do feel like I'm on my own. (Elizabeth)

A group of parents described being “trapped” by their child who was reliant on them to go out, sleep and/or eat. Caring for their child had reverted to a time when their child was younger, dependent on them to function in daily life.

It's got to a stage where I've got to come at lunch time to make sure she has something to eat… She won't ever leave her house on her own… I would say she's gone back at least 4‐years mentally. She's much more like she wants to be at home, clingy. (Jennifer)

As a combined result of these three factors, parents distrusted health professionals and hospital services. They sought alternative opinions at different hospitals that could offer second opinions, new investigations, or treatment options. Parents used private health services and prioritized these appointments even when they placed a financial burden on the family. This cycle could continue with their child moving further away from recovery.

I've spent so much money on alternative therapies and the osteopath over the years because we'd get to the point of desperation when you would do anything to help your kids… it's really upsetting and frustrating that you're constantly asking for help, and nobody is really helping. (Sarah)

2.8. Theme 3: “Drawing a line under it”

Just over half the parents reached a point during treatment when they no longer fought for answers and solutions. Their outcome focus was their child's functioning, and family functioning. Nearly all these parents described their child as “better” or “improved” in comparison to the start of treatment. One parent who described their child as worse, had only recently (weeks prior to the interview) found a multidisciplinary team she trusted and a diagnosis she understood. These parents shared common characteristics; they believed in the diagnosis and management plan, perceived they were on the right track with the right people, and described a massive sense of “relief.”

From a parent perspective, to have, almost, to draw a line under it, like this is what the problem is, and this is how we're going to fix it, and yes, we've seen it before…and it gets better. (Thomas)

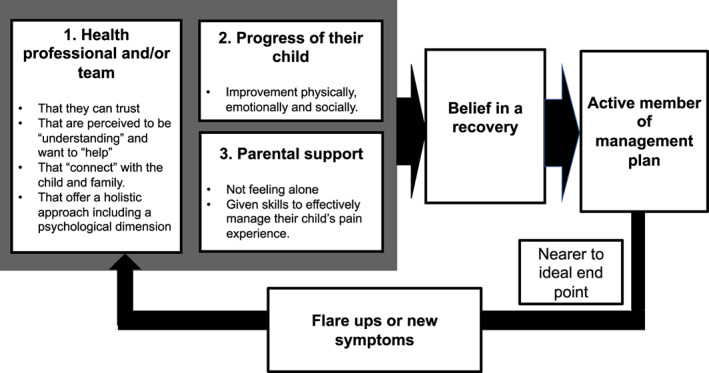

As shown in Figure 3, three key features allowed parents to feel they no longer needed to fight to protect and advocate for their child: (1) trusting the health professionals they were working with; (2) observing positive change in their child and (3) having support to effectively make changes to their parenting, to facilitate their child's recovery.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of the theme “drawing a line under it.”

These parents had received a diagnostic explanation that fitted their existing beliefs. The majority found the explanation of chronic pain described as an increased sensitivity of the nervous system linked with the belief there was “something wrong” and allowed the exploration of how emotions can increase and decrease the sensitivity of the nervous system, integrating physical and psychological components. This explanation also fitted with the treatment plan, that “the nerves just need to be reprogrammed” and this was reversible.

Her brain is sending wrong signals which means she's in pain randomly, different places, different times, she gets nausea, she gets dizziness, she gets fatigued…finally someone is listening, someone for her has gone yes I believe you and yes it's real, no you don't need to go to a teenage drop in centre…it was such a relief I guess and a form of happy and then I think for both of us over a couple of days that went “ahhhhh”[relief] when we got the diagnosis. (Crystal)

The first moments with a healthcare professional who took the time to listen and validate their experience were described as “surreal” by parents because of the length of time it took to happen. Parents described this personal connection as the same feeling you get when you realize a teacher “gets your kid”: When they sensed a health professional understood their child in the same way as they did, they felt able to relax.

I like that she saw [my child] …it's a heart thing I think actually, but equally it's an external thing in that [the doctor] will move a chair and you know, she's making eye contact, she's 100% there in that situation with your child. And also, I didn't feel like I was a nuisance I was an add‐on… You know when people care. (Jemima)

Parents observed health professionals working with their child to set goals, and saw a route to recovery: They watched, as their child made “incredible” and “dramatic” positive changes.

[My child's] mindset really changed, and it was ‘do you know what, I am going to get over this, I just want to get on with things now, I want to be back to normal doing all the things I love.’ (Nicole)

When their child had a “flare” or when a new pain or symptom appeared, parents felt able to contact the health team directly. They were reassured that this was not unexpected, that it would improve and most importantly, they were doing the right thing continuing with the current approach.

They said if there is any inkling if you think this is happening again or whatever just come straight back…because I think that was my worry. (Amanda)

Health professionals became a source of support, and parents no longer felt alone.

The best thing I think for me was having [the physiotherapist] to be able to ring him up and go… ‘I don't know what to do’ and him saying ‘come in’. I feel he's our supportive network… I think when you're dealing with something like this, you need constant. (Megan)

With health professionals on their side, parents described the confidence to respond to their child differently. This change occurred for some parents once they understood and believed the diagnosis and management plan, whereas for other parents, a specific education session given to parents by a psychologist initiated a parenting change. One parent described how this change occurred when the safeguarding team were involved and contact between their child and a family member was stopped. The common theme in this parenting shift was “non‐judgmental boldness” where parents would not judge their child, instead they would just “get on with it”. Parents appeared to be no longer scared of pushing their child to do things because they believed the pain was “just pain” and not an indication of damage. Melissa reflected on a time she was “fighting in the dark” and compared this time to the new optimism she had found.

I was busy doing stuff that I thought was right but actually what it came down to was the psychology of me being strong for her…I found a psychologist that I wanted to continue with…I've found just an optimism and I just say to her, I say to [my child] ‘now you're doing it, you know you are going to get better’, so it's amazing how sort of doors open, erm so yes I think both of us have changed. (Melissa)

Matthew described times in the past when they would plan to visit friends and their child would say “I don't want to” and then they would not go, now they say, “we are doing this” and they go. Rather than feeling helpless, parents realized this approach improved their relationship with their child, ultimately, they felt like a “good parent.”

My approach has changed…I feel that our relationship is improved…in fact I don't know that she's said at all to me, no she hasn't, things like ‘you don't care, you don't understand, you don't take me seriously’ …you feel like you're being a better mother. (Amy)

2.9. Theme 4: “Free”

When their child reached the end of treatment parents described their own escape. They portrayed an image of a heavy cloud being lifted off the whole family, like a “weight taken off” and “lighter.” Parents highlighted the importance of being able to make plans for holidays, events, or family activities without limitations.

Not having to plan around [my child's] pain…pain being out of all our heads…we don't have to think about it anymore. Not pre‐empt situations or wonder how she is…is she putting on a brave face. (Stephanie)

Parents also described the return of normality for them and their child, a “happy house,” busy doing “normal” things, where life would be “easier” and more “fun.” As parents, they felt they could return to work, pursue their own interests, and divide their attention more evenly between siblings. The cost of hospital parking, travel, private appointments, and loss of earnings was no longer a concern. Their child would have spontaneity and freedom, being confident in their abilities.

To be able to do things, to be confident and assured and less cautious, just to be more free with it. (Amy)

Socially, their child would be able to meet their friends, return to their sports, and develop their independence.

Just to have [my child] back socially…you name it she would do it, cinema, trampolining, gymnastics, dance, ride her bike to the park, just goes up and meets [friends] at McDonalds or Starbucks. (Elizabeth)

A large group of parents discussed their child not having pain and being “pain‐free” at this final stage. While the elimination of pain was important, a group of parents did not discuss pain at the end of their child's treatment. Parents expressed the desire to have their “[child] back,” a child who was happy, physically able and “well.” Parents wanted to see their child more “relaxed” and “carefree” with a return of their “confidence” and “personality.”

Just hearing laughter. Laughter is a really important thing… Your priorities change when something like this happens… [name] has always been really academic, very high achieving and suddenly that doesn't matter…I'd just like her to be happy. (Ashley)

Lastly, a group of parents discussed the importance of their child learning long‐term management strategies or “self‐help.” The expectation was that their child would have a better understanding of their body, so they would know “how to avoid pain” and pain would not become “part of [their] identity.” Some parents expected a “practical management plan,” to enable their child to independently manage their pain and reduce any reliance on pain medication. Parents highlighted the importance of having access to services into adulthood, services that could give a “holistic approach” including “mental health support.”

3. DISCUSSION

In this cohort of 21 parents of children with chronic pain a range of complex and interconnected outcomes was identified over the course of treatment. Outcomes identified by parents, initially focused on the treatment experience and their child's pain. While pain intensity is a consistently measured outcome within clinical trials, outcomes relating to the treatment experience of chronic pain are rarely measured 20 , 21 and have not been previously prioritized. 13 The outcomes parents considered important did change during treatment, with just over half of the parents demonstrating a point in time (“drawing a line under it”) when their child's functioning, and family functioning, became more important before the final theme “free.” This transition, when the focus of parents changed, appeared pivotal to the recovery of young people.

All parents described being initially preoccupied in finding services that could establish the cause of their child's pain and then effectively treat it, so their child would be returned to person they were before it started. Jordan et al. 6 described how parents fought for services to assert some control over their child's situation; however, young people who recover from chronic pain appear to make their own decision to change 18 , 22 and young people experiencing mental health conditions considered parental expectation that services could “fix” them were unrealistic. 23 In adolescence, young people are becoming autonomous and independent, and the parent–child relationship is reorganized. 24 , 25 When parents fought for their child, they are potentially reverting to a dominant parenting style, more indicative of earlier childhood, and taking away a young person's perceived control over their situation. O'Sullivan 26 expressed concern for this future generation who are taken by their parents on a quest for a diagnosis and disempowered by the situation.

Parents could “draw a line” under their search for help and focus on their child's functioning, physically, emotionally, and socially. One explanation for this shift in outcome focus could be a change in parenting goals. Three universal parental goals are outlined by LeVine 27 : (1) keeping a child alive and healthy; (2) developing a child's capacity to be economically independent and; (3) developing a child's behavioral capacity to maximize other cultural values, for example, academic achievement, personal satisfaction, and self‐realization. Parents “fighting in the dark” from their perspective, did not have an accepted explanation for their child's pain and feared something was medically wrong. The first parental goal of survival had been threatened and become their foremost concern. The natural hierarchy of Levine's goals 27 would require parents to understand their child's pain was not an indication of serious disease, illness or damage, before being able to prioritize higher parenting goals such as developing their child's independence and personal satisfaction. The importance of parents shifting their focus toward their child's “wellness” rather than “illness” is well documented within cognitive behavioral therapy trials for functional abdominal pain affecting children (aged 7–17 years) in the United States. 28 , 29 , 30 These functional abdominal pain studies highlight the importance of changes in process outcomes including reducing parental solicitousness, reducing the perception of threat associated with pain (pain beliefs) and improving coping skills. These process outcomes reflect the descriptions given by parents in the current study and could help explain this parental change in outcome focus.

Another consideration, is that when parents trusted and felt supported by a health professional, they no longer felt alone. Parents felt supported and encouraged to change how they responded to their child, and thus their vision of what was a “good parent” altered. This re‐evaluation of parenting was a theme previously established in other qualitative studies 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ; however, the actual shift and moment in time that a line was drawn, and why that occurred, had not been established. The original “good parent” belief concept was introduced by Hinds et al. 31 and the existing research on the concept was summarized by Weaver et al. 32 who clarified good parent beliefs were dynamic and could be promoted or hindered by health professional behavior. The dynamic component of this belief was demonstrated by Hill et al. 33 however, the study involved children with serious illness, and this concept has not been explored with parents of children experiencing chronic pain.

The final theme “free” described a successful endpoint of treatment and highlighted outcomes related to both child and family functioning. Looking across the four themes, this current study gives a sense of order to outcomes that were important to parents. Although existing qualitative studies have highlighted the importance of a diagnosis 5 , 6 , 8 , 9 , 10 and a good parent–health professional relationship, 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 in isolation these themes did not give the reader a sense of their build‐up, consequences or interaction, yet these factors have been the most illuminating. The re‐evaluation of parenting, and parents becoming an active role in their child's rehabilitation, was a consequence of parents: (1) trusting the healthcare team and their diagnosis; (2) gaining their own support; (3) seeing a positive change in their child. Parents appeared to require all three aspects to make this shift. If their child made an improvement, this could transiently stop the fight, however, on return of symptoms, without support or trust in a healthcare team, hope of a recovery was diminished again, and parents returned to fighting to find a resolution. Although the existing research had established that parents fought for resources, factors that allowed parents to end their fight were missing, and the implications of this shift to their children's recovery, were also not discussed.

Clinical implications highlighted by the present study include the importance of establishing the beliefs and expectations of parents and tailoring support. It is important to see the whole family picture, being vigilant to any safeguarding concerns and escalating these as appropriate. Services should invest time with parents, ensure they understand why their child is experiencing pain, give parents the confidence to have “non‐judgmental boldness” and reassure them they are being a “good parent” for taking this stance despite their child displaying symptoms. Equally, health professionals need to reflect on their own actions; are they responding to a child's pain in the same way as parents? Are they searching for a solution and taking away a child's perceived control? They may need to take a step back and recognize their role in empowering young people to navigate their own path to recovery.

It is important to identify limitations of the current research. Recruitment was from two hospital sites within England and therefore the opinions of parents represented may not reflect the experiences of parents in different services or cultures. This qualitative study involved seeing parents, who chose to participate, in different settings. Interaction with the researcher and volunteer bias, may have influenced the responses. Family dyads were not evaluated or compared however, in the theme “fighting in the dark” responses highlighted potential disparities in parenting, pain beliefs and expectations of treatment that warrant further investigation. The togetherness of parents when parenting their child experiencing persistent pain, was also something that was suggested by parents as important. Parents raised the issue that siblings should have the opportunity to express their opinion, suggesting future studies could explore their viewpoint. Outcomes relating to how families and parents function were unrecognized as an outcome domain in chronic pain studies and therefore this domain requires further investigation.

In conclusion, the perceived stage of their child's treatment influenced the outcomes parents considered important. Some parents could “draw a line” under the diagnosis and treatment plan and become an active role in their child's treatment by empowering their child to make positive steps in their own life. For these parents, their outcome focus was their child engaging with life, physically, emotionally, and socially. Outcomes also went beyond the young person and included parent and family functioning. On the contrary, some parents continued to fight for a solution to relieve their child's pain, and outcomes related to the pain and the treatment experience were the focus. Changing the outcome focus of parents during treatment appeared to be pivotal to the young person's recovery and reflects the vital role parents have within the treatment of their child's chronic pain.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Health Service (NHS, Leeds, UK) Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 18/SC/0138).

PATIENT CONSENT

Informed written consent was provided by all participants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy, Private Physiotherapy Fund and Association of Pediatric Chartered Physiotherapists, UK supported educational fees.

Joslin R, Donovan‐Hall M, Roberts L. “You just want someone to help”: Outcomes that matter to parents when their child is treated for chronic pain. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2023;5:38‐48. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12098

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarthun A, Akerjordet K. Parent participation in decision‐making in health‐care services for children: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag. 2012;22(2):177‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Park ES, Cho IY. Shared decision‐making in the paediatric field: a literature review and concept analysis. Scand J Caring Sci. 2018;32(2):478‐489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Guidelines on the Management of Chronic Pain in Children. World Health Organization; 2020: Licence: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Howard RF, et al. Delivering transformative action in paediatric pain: a lancet child & adolescent health commission. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:47‐87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaughan V, Logan D, Sethna N, Mott S. Parents' perspective of their journey caring for a child with chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15:246‐257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan AL, Eccleston C, Osborn M. Being a parent of the adolescent with complex chronic pain: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:49‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jordan A, Crabtree A, Eccleston C. 'You have to be a jack of all trades': fathers parenting their adolescent with chronic pain. J Health Psychol. 2015;21(11):2466‐2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maciver D, Jones D, Nicol M. Parental experiences of pediatric chronic pain management services. J Pain Manag. 2011;4:371‐380. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carter B. Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: professional ventriloquism and hidden voices. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:28‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neville A, Jordan A, Beveridge J, Pincus T, Noel M. Diagnostic uncertainty in youth with chronic pain and their parents. J Pain. 2019;20:1080‐1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gorodzinsky A, Tran S, Gustavor. Medrano K, et al. Parents' initial perceptions of multidisciplinary care for pediatric chronic pain. Pain Res Treat. 2012;2012:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mcgrath PJ, Finley GA, Walco GA, et al. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771‐783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palmero TM, Walco GA, Paladhi UR, et al. Outcome set for pediatric chronic pain clinical trials: results from a delphi poll and consensus meeting. Pain. 2021;162(10):2539‐2547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hurtubise, K. , Brousselle, A. , Camden, C. And Noel, M. 2020, What really matters in pediatric chronic pain rehabilitation? Results of a multi‐stakeholder nominal group study. Disabil Rehabil, 42(12): 1675–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jordan A, Eccleston C, Crombez G. Parental functioning in the context of adolescent chronic pain: a review of previously used measures. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:640‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adriansen HK. Timeline interviews: a tool for conducting life history research. Qual Stud. 2012;3(2):40‐55. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joslin R, Donovan‐Hall M, Roberts L. Exploring the outcomes that matter most to young people treated for chronic pain: a qualitative study. Children. 2021;8(12):1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hechler T, Kanstrup M, Holley AL, et al. Systematic review on intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment of children with chronic pain. Pediatrics. 2015;136:115‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liossi C, Johnstone L, Lilley S, Caes L, Williams G, Schoth D. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary interventions in paediatric chronic pain management: a systematic review and subset analysis. Br J Anesth. 2019;123:359‐371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meldrum ML, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. 'I can't be what I want to be': children's narratives of chronic pain experiences and treatment outcomes. Pain Med. 2009;10:1018‐1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Law H, Dehmahdi N, Carney R, et al. What does recovery mean to young people with mental health difficulties? – “It's not this magical unspoken thing, it's just recovery”. J Ment Health. 2020;29:464‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hadiwijaya H, Klimstra TA, Meeus WHJ, Vermunt JK, Branje SJT. On the development of harmony, turbulence, and independence in parent‐adolescent relationships: a five‐wave longitudinal study. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46:1772‐1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meeus W. Adolescent Development: Longitudinal Research into the Self, Personal Relationships and Psychopathology. Routledge; 2019:50‐63. [Google Scholar]

- 26. O'Sullivan S. The Sleeping Beauties and Other Stories of Mystery Illness. Picador; 2021:273‐318. [Google Scholar]

- 27. LeVine RA. Parental goals: a cross‐cultural view. Teach Coll Rec. 1974;76:226‐239. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levy RL, Langer SL, Dupen MM, et al. Cognitive‐behavioural therapy for children with functional abdominal pain and their parents decreases pain and other symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:946‐956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levy RL, Langer SL, Van Tilburg MAL, et al. Brief telephone‐delivered cognitive behavioral therapy targeted to parents of children with functional abdominal pain: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2017;158:618‐628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Levy RL, Langer SL, Walker LS, et al. Twelve‐month follow‐up of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with functional abdominal pain. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:178‐184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. "Trying to be a good parent" as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5979‐5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weaver MS, October T, Feudtner C, Hinds PS. “Good‐parent beliefs”: research, concept, and clinical practice. Pediatrics. 2020;145(6):e20194018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hill DL, Faerber JA, Li Y, et al. Changes over time in good‐parent beliefs among parents of children with serious illness: a two‐year cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58:190‐197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.