Abstract

The purpose of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to methodically integrate peer-reviewed findings regarding lateral violence within Indigenous communities, with particular attention to the experiences of Indigenous women. Lateral violence describes aggression within systemically exploited groups. Interpretations from eligible articles were informed by intersectionality theory and post-colonial theory. Eligibility criteria included quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed articles on lateral violence within Indigenous communities. Only articles that were primary sources, available to download in English, and published between 2000 and 2021 were included. Samples did not need to consist of Indigenous women exclusively, but Indigenous women had to be included. First, advanced searches were conducted in five databases (Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, Indigenous Peoples: North America, ProQuest: Sociology Collection, and ERIC). Second, a multidisciplinary index (Google Scholar) was searched. Third, 23 peer-reviewed journals specializing in Indigenous topics were systematically searched. Lastly, forward and backward snowballing techniques were implemented. Articles were appraised following PRISMA-P guidelines. Ten articles passed the eligibility criteria. Findings suggest that lateral violence within Indigenous communities is a complex social concern, with participants disclosing both survivorship and contribution to lateral violence. Within Australian and Canadian contexts, lateral violence experiences are prevalent and persistent occurrences. Lateral violence is a controversial and taboo topic and is often silenced or normalized within Indigenous communities. For this reason, further research is warranted to raise awareness of lateral violence to disrupt the cycle of internalized oppression.

Keywords: Lateral violence, Indigenous women, intergenerational trauma, community violence, systematic literature review

Lateral violence is a term that describes aggression within systemically exploited groups (Freire, 2000; Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2015). Other terms used to describe this concept include horizontal violence and infighting (Burnette, 2015; Clark, 2015). Common behavioral manifestations of lateral violence include bullying, gossiping, shaming, intimidation, and sabotaging (Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2015). The detrimental consequences of lateral violence have been documented at various socio-ecological levels of analysis. For instance, at the macro-level, perceptions of toxicity within communities have been reported as a barrier to the continuity of Indigenous cultures and as a factor influencing acculturation (Auger, 2016). At the meso-level, lateral violence occurring in Indigenous workplaces has resulted in community members feeling unsupported and distressed (Cooper & Driedger, 2019; Wickham, 2013). Additionally, lower self-esteem and wellbeing resulting from experiences of lateral violence at the micro-level have been analyzed (Bennett, 2014).

Lateral violence is widely recognized as a product of internalized historical and contemporary oppression. The etiology of lateral violence has been theorized to have emerged from the complex trauma and devastating staff-perpetrated and student-to-student abuse experienced in residential schools (Bombay et al., 2014). Burnette (2015) proposed a model depicting a layered context of historical oppression within Indigenous communities. Within this model, lateral violence is described as a mechanism of oppression that permeates across layers of oppressive experiences, historical and contemporary loss, cultural disruption, manifestations of oppression, and dehumanizing beliefs and values (Burnette, 2015). Moreover, the complexities of lateral violence experiences may be interpreted with the aid of frameworks put forth by intersectionality theory and post-colonial theory.

Theoretical Framework

Intersectionality Theory

Intersectionality theory developed out of recognizing that human and social experiences—discrimination and privilege—are impacted by various socially constructed categories concurrently (Cole, 2009; Grzanka, 2020). It became apparent to founding theorists that studies of sexism, racism, and class alone could not account for the most marginalized (Grzanka, 2020). Theories that focus solely on one category are not equipped to explain the oppression or privilege unique to overlapping categories. Crenshaw (1989) was the first scholar to coin the term “intersectionality” in the late 1980s to describe simultaneous positions within social categories (as cited in Cole, 2009; Marecek, 2016). Crenshaw argued that the experiences within, between, and overlapping social categories might be similar, additive and specific (as cited in Cole, 2009).

Intersectionality theory analyzes human and social experiences at the sociocultural level (Marecek, 2016). Through the lens of intersectionality theory, individuals’ experiences of power and oppression are viewed within the context of these intersecting social structures. Intersectionality theory is concerned with social categories such as gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status/class, race, ethnicity, and ability. The theory is anti-essentialist (Samuels & Ross-Sheriff, 2008). It emphasizes how people experience these categories in non-insulated ways (Cole, 2009). According to the framework, it would be fragmentary to analyze experiences in partitioned ways. For instance, it would be incomplete to describe a person’s social experiences only through the framework of gender or only through the lens of race (Cole, 2009). Doing so would only offer limited interpretations and fail to address the complexities of intersecting social identities. Additionally, intersectionality theory asserts that context impacts how positions within social categories are evaluated (Samuels & Ross-Sheriff, 2008).

Tools have been developed to help researchers apply an intersectional framework to their work. Cole (2009) developed three questions to guide intersectionality-informed research:

1. How representative is the diversity within the sample of interest?

2. How is social inequality affecting the situation or experience?

3. What are the differences and similarities between, within, and overlapping experiences associated with social positions?

Approximately a decade later, Grzanka (2020) added three additional questions to this research guideline:

1. How can this situation be analyzed from a structurally competent or systemic perspective rather than an identarian or individualistic perspective?

2. What is the role of social power?

3. How can social change be brought about?

Both researchers stated that an intersectional framework does not require a complete methodological overhaul concerning research methods. Instead, Cole (2009) and Grzanka (2020) offered paradigm shifts in thinking and approach when conducting research. By keeping questions like the ones outlined above in mind, researchers can investigate privilege and oppression through the broad lens of intersectionality.

Aligned with the theoretical lens of intersectionality, the participants within the reviewed articles of this systematic literature review (SLR) will be acknowledged by their simultaneous positions within social categories. According to intersectionality theory (Cole, 2009), Indigenous women’s experiences may be similar, additive, or specific to the experiences of others who identify with different positions within social categories. For example, Indigenous women’s experiences with lateral violence may be similarly like the experiences of other gender identities within Indigenous communities or similarly like women’s experiences within other ethnic groups. Their experiences may also be additive, whereby discrimination and oppression are compounded by inhabiting marginalized positions in both gender and ethnic group categories. Likewise, Indigenous women’s experiences of lateral violence may be unique or specific to their social position. The concept of the matrix of domination from intersectionality theory is also relevant to the current study’s population and topic. The matrix of domination illustrates how intersecting positions within social categories are related to experienced oppression and privilege (Grzanka, 2020). Additionally, when discussing intersectionality theory, Samuels & Ross-Sheriff (2008) considered how women might oppress women. These experiences are directly relevant to the aim and scope of the current study and offer a rationale for why this present SLR focuses primarily on lateral violence experiences of Indigenous women.

Post-Colonial Theory

As the name suggests, post-colonial theory responds to the oppression from European colonialism dating back to the 16th century (Parsons & Harding, 2011). Post-colonial theory aims to disrupt the unjust effects and systems put in place by colonialism. This aim is grounded by principles of reciprocity, reflexivity, and reflection (Parsons & Harding, 2011). Post-colonial theory investigates the responses to oppressive control, exploitation, cultural discourses, and injustices created by colonialism (Saada, 2014). A common theme in post-colonial theory is to investigate the construction of the Eurocentric “us” versus “them” (i.e., all other cultures). The heterogeneity of variance within this “other” category often is disrespected. As Saada (2014) explains, cultures not of European descent are often represented as one homogenous group in a post-colonial society. The doctrine of colonialism has historically and, in many ways, continues to paint a binary picture of Western cultures and peoples versus non-Western cultures and peoples.

Post-colonial theory has been applied to a wide variety of scholarly fields. This is primarily due to the pervasive historical context and ongoing effects of European colonialism prevalent across many domains (Saada, 2014). Many institutions and systems in Western society have contributed to the marginalization of colonized cultures (Parsons & Harding, 2011). This involvement cannot be ignored or forgotten, both out of respect for historical context and the lasting effects of such injustices. For instance, the patriarchal values and sexism embedded in the Indian Act of 1876 have added to the colonial injustices experienced by Indigenous women (Gerber, 2014). Further, Western educational and religious institutions, such as residential schools in Canada, served as oppressive systems that punished cultural practices, language, religion, epistemologies, and customs that differed from those of the oppressor (Bombay et al., 2014). Post-colonial theory acknowledges and understands the traumas, social inequities, and injustices from such colonial practices (Parsons & Harding, 2011). Reparation and reconciliation efforts and the struggles of navigating and reclaiming a marginalized cultural identity within a “post-colonial” society are addressed within this framework.

Post-colonial theory examines and challenges the historical and ongoing practices of silencing the voices, perspectives, and customs of non-Western cultures and peoples. Denying the epistemologies of other cultures is a form of oppression. Within the post-colonial theoretical framework, imposing Western ways of knowing onto non-Western cultures and disregarding their epistemologies is referred to as epistemic violence (Saada, 2014). Similarly, the act of imposing Western cultural norms and values onto other cultures as a form of oppression and control is of interest in post-colonial studies. This process has been referred to as “worlding” and is commonly masked by attempts to “civilize” the “other” (Saada, 2014). This oppressive silencing may be countered with a post-colonial theoretical framework method referred to as contrapuntal analysis. This form of analysis requests that the hidden contexts, intentions, and perspectives of the “other” be revealed to produce more complete interpretations.

Post-colonial theory is relevant to research about populations, practices, and systems affected by colonialism. Lateral violence within Indigenous communities has been widely recognized as a consequence of colonialism (Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2015), making it an appropriate area of study to be informed by a post-colonial theoretical lens. Post-colonial frameworks have been applied to research on Indigenous Peoples’ experiences with residential schools (Parsons & Harding, 2011); therefore, its application and relevance to other experiences related to intergenerational traumas and colonial legacies seem appropriate. Post-colonial theory emphasizes the value of including the perspectives and epistemologies of oppressed cultural groups (Parsons & Harding, 2011). This recognition contrasts with the colonial trend to impose Western ways of knowing onto non-Western cultures and peoples (Saada, 2014). Reconciliation is a crucial component of post-colonial theory (Parsons & Harding, 2011), which relates to this current review’s objectives.

Current Objectives

The availability of peer-reviewed primary literature specifically addressing lateral violence within Indigenous communities is scarce. The majority of current research only discusses lateral violence briefly (e.g., Cooper & Driedger, 2019; Fraser et al., 2019; Johnstone & Lee, 2021). Some researchers have advanced the need to further explore this issue following comments made by participants when discussing wellness and cultural identity within Indigenous communities (Wilson, 2004).

The purpose of this SLR is to methodically integrate peer-reviewed findings regarding lateral violence within Indigenous communities, with particular attention to the experiences of Indigenous women. Such a review is needed to highlight potential methodological considerations and knowledge gaps that may be addressed in future research to enrich the study of lateral violence within Indigenous communities. Consistent with the goals of the reviewed articles, meaningful implications relevant to Indigenous communities affected by lateral violence will be discussed.

Method

Eligibility Criteria

Initially, inclusion criteria for this SLR necessitated samples to consist entirely of Indigenous women. For this reason, the rationale for a gender-specific criterion was informed by the intersectional theoretical framework guiding this review and the intention to investigate Indigenous women’s specific experiences with lateral violence. However, due to the dearth of peer-reviewed literature on lateral violence within Indigenous communities, it soon became apparent that eligibility criteria would need to be modified. Eligibility criteria were adapted to include quantitative and qualitative peer-reviewed articles investigating direct or vicarious experiences of lateral violence within Indigenous communities. It was stipulated that articles would be primary sources available for download in English and be published between 2000 and 2021. Samples did not need to consist of Indigenous women exclusively; however, Indigenous women did need to be included. This meant that samples that included other gender categories or non-Indigenous participants would also be considered for this SLR.

Search Strategy

The search strategy employed in this SLR consisted of four phases. Table 1 lists search terms used across searching phases. First, advance searches were done in five academic databases (Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, Indigenous Peoples: North America, ProQuest: Sociology Collection, and ERIC) with limiting functions to impose eligibility criteria on search results. Database-specific controlled vocabularies were utilized to broaden results. Second, a multidisciplinary index (Google Scholar) was searched. Third, 23 peer-reviewed journals specializing in Indigenous topics were systematically searched. Fourth, forward and backward snowballing techniques were implemented to search sources cited within eligible articles and for recent sources that cited the articles identified as eligible in this SLR.

Table 1.

List of Search Terms.

| Indigenous a | Women | Lateral Violence |

|---|---|---|

| (Indigenous OR “Indigenous Peoples” OR “Indigenous populations” OR Aboriginal OR “Aboriginal peoples” OR “First Nations” OR “First Peoples” OR Inuit OR Métis OR Native OR Indian) | (Women OR Female) | (“Lateral violence” OR auto-genocide OR bloodism OR “colonial trauma” OR “community-based aggression” OR “community-based bullying” OR “community-based discrimination” OR “community-based feuding” OR “community-based violence” OR “historical trauma” OR “horizontal aggression” OR “horizontal violence” OR infighting OR “intergenerational transmission” OR “intergenerational trauma” OR “intergenerational violence” OR “internalized colonization” OR “internalized racism” OR intraraci* OR intra-raci* OR “lateral aggression” OR “minority-on-minority” OR “multigenerational trauma” OR “oppressed oppressor” OR “residential schools legacy” OR “residential schools trauma” OR “residential schools violence” OR “student-to-student abuse”) |

aSome of the terms related to the concept of “Indigenous” are outdated and potentially offensive (specifically, the terms “Native” and “Indian”). However, such terms were included due to their historical usage in some literature and legislation.

Article Appraisal and Data Extraction

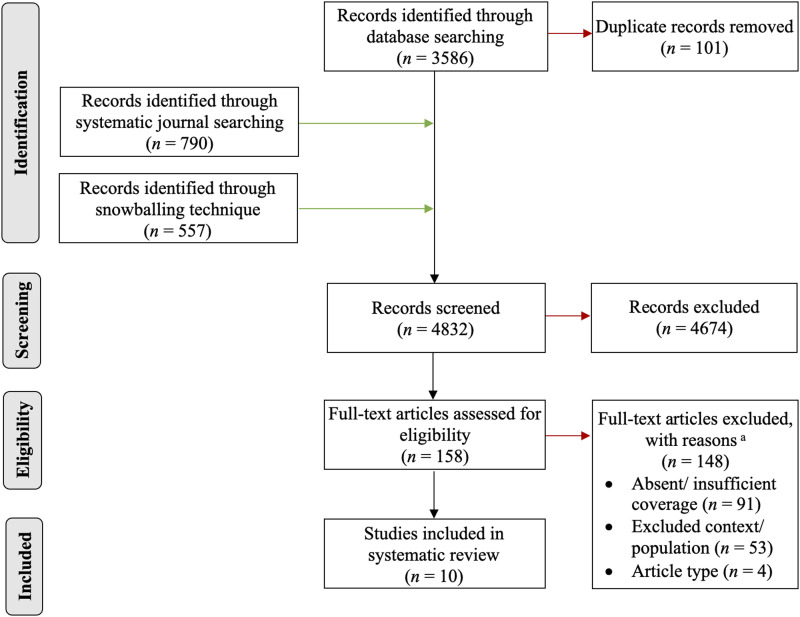

Procedures for appraising and extracting data from articles were followed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines (Shamseer et al., 2015). Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA-P search and appraisal flowchart. Reasons for article exclusion were kept in a record management system, which consisted of a spreadsheet to track searching, eligibility notes, and piloted data extraction forms along with a reference management software to store, tag, and organize article appraisal outcomes. Common reasons for exclusion included (a) lack of or only brief mention of lateral violence, (b) incorrect population or context (e.g., non-Indigenous nursing), and (c) ineligible article type (e.g., reviews or commentaries). Relevant information was extracted from articles that met eligibility criteria in a piloted extraction spreadsheet. In full, 10 articles passed the eligibility criteria and are included in this SLR. Of these 10 eligible articles, six were retrieved from Google Scholar, two were retrieved from hand-searching peer-reviewed journals specializing in Indigenous topics, and two were found while using the forward snowballing technique. A summary of reviewed articles is offered in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-P Search and Appraisal Flowchart. Note. PRISMA-P = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols. Adapted from Moher et al. (2009). Copyright by 2009 Moher et al. aArticles were appraised for coverage of lateral violence, population, and type, in that order.

Table 2.

Summary of Reviewed Articles (n = 10).

| Author(s) and Date | Sample | Location(s) | Method | Key Findings a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bailey (2020) | Indigenous women and men, undergraduate students (n = 27) | Ontario, Canada | Qualitative interviews | Two key themes: (a) Lateral violence is common and its effects are far-reaching and (b) Indigenous students are resistant and resilient to lateral violence |

| Bennett (2014) | Indigenous women, undergraduate students (n = 10); Indigenous men, undergraduate students (n = 5) | New South Wales, Australia | Qualitative interviews | Three key themes: (a) Difficulties of lateral violence experiences, (b) lateral violence experiences specific to being lighter-skinned, and (c) positive impact of support systems |

| Clark (2015) | Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) women (n = 19); Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) men (n = 11) | Adelaide, Australia | Qualitative interviews | Five key themes: (a) “Understanding the concept before a label” (p. 25), (b) acceptance of the label, (c) disapproval of the label, (d) past labels that named the concept, and (e) having a label made the issue more concrete |

| Clark et al. (2016) | Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) women (n = 19); Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) men (n = 11) b | Adelaide, Australia | Mixed: Quantitative questionnaires with qualitative interviews | Quantitative results: Measured wellbeing |

| Four key themes: (a) Covert nature of lateral violence, (b) influences of racism, (c) impact on identity, and (d) impact on wellbeing | ||||

| Clark et al. (2017a) | Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) women (n = 19); Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) men (n = 11) | Adelaide, Australia | Qualitative interviews | Seven key themes: (a) The importance of education, (b) support is protective, (c) importance of role models, (d) cultural identity is protective, (e) avoidance may be protective, (f) lateral violence may be resisted, and (g) coping may involve positive reinterpretation |

| Clark et al. (2017b) | Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) women (n = 41); Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) men (n = 17) c | Adelaide, Australia | Mixed: Quantitative questionnaire with open-ended qualitative questions | Quantitative results: Developed a workshop evaluation questionnaire. Overall, evaluation was positive, and benefits were maintained. Themes were assessed pre-, post-, and three months post-workshop |

| Four key themes: (a) Lateral violence terminology, (b) lateral violence experiences, (c) lateral violence impacts, and (d) strategies and skills to intervene | ||||

| Clark et al. (2017c) | Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) women (n = 4); Indigenous (Torres Strait Islander) men (n = 3) | Adelaide, Australia | Qualitative interviews | Three key themes: (a) Workshop feedback was positive, (b) identification of support needs, and (c) sharing of prevention strategies |

| Monchalin et al. (2020) | Indigenous (Métis) women (n = 11) | Toronto, Ontario, Canada | Qualitative interviews | Two key themes: (a) Lateral violence experiences while working in an Indigenous health setting and (b) while accessing services from an Indigenous health setting |

| Stoor et al. (2019) | Women (n = 15) and men (n = 7) of which were both Indigenous (Sámi) (n = 20) and non-Indigenous (n = 2) | North, South, Lule, Marka, and coastal Sámi communities, Norway | Qualitative focus groups | One key theme: Sámi to Sámi aggression was one of the six identified themes relating to cultural meanings of suicide |

| Van Bewer et al. (2021) | Indigenous (First Nations, Métis, and Cree) and non-Indigenous women (n = 15) d | Manitoba, Canada | Qualitative forum theatre | Four key themes: (a) Identity navigation and disclosure, (b) lateral violence experiences, (c) lack of cultural safety, and (d) tokenism |

aOnly key findings relevant to lateral violence are summarized.

b21 participants participated in the quantitative portion of this study.

cPost-evaluation and three months post-evaluation sample sizes differed (n = 58 and 23, respectively).

dTotal sample was divided into a forum theatre actor group (n = 8) and an audience member group (n = 7).

Data Synthesis

The majority of eligible articles were qualitative, so extracted data and article notes were synthesized thematically using NVivo 1.0. Data synthesis was conducted by a trained research assistant (the third author). The second author is an Indigenous Scholar who oversaw the analysis and write up of this SLR. This current study is part of a larger project stemming from the second author’s doctoral dissertation on Indigenous women who survived residential schools (Stirbys, 2016). In total, 44 categories were coded. The process of grouping categories into themes was informed by the theoretical assumptions of intersectionality and post-colonial theories, the aim of this SLR, how many note references and eligible articles were associated with each category, and the similarity between content. The resulting themes constitute the headings in this SLR’s Results section and are visually depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Visualization of Themes.

Results

Prevalence, Forms, and Outcomes

Findings from the reviewed literature suggest that lateral violence within Indigenous communities is a common social concern. Interviews with Indigenous students revealed that 65% of participants experienced lateral violence in university (Bailey, 2020). In a study that evaluated an educational lateral violence workshop’s outcomes, many participants identified with being on the receiving end of lateral violence (Clark et al., 2017b). Many also took ownership for contributing to lateral violence (Clark et al., 2017b). In addition to the high prevalence within Indigenous communities in Australian and Canadian contexts, lateral violence experiences tended to be persistent occurrences rather than one-time issues (Bailey, 2020). Across many studies, lateral violence took various forms, with participants describing both overt and covert behaviors occurring within their communities. Examples of overt lateral violence included murder (Clark et al., 2016); however, most reported lateral violence instances tended to be covert, with 96% of reported lateral violence behaviors being covert in one sample (Clark et al., 2017b). Common actions inflicted and experienced included bullying, gossiping, intimidation, shaming, accusations, enforcing social hierarchies, infighting, and social/cultural exclusion (Bailey, 2020; Bennett, 2014; Clark et al., 2016; Monchalin et al., 2020; Stoor et al., 2019). Sámi peoples reported intragroup stigmatization of mental health, sexual orientation, and family association (Stoor et al., 2019). Social media, like Facebook, was a common tool used to affirm or challenge perceptions of Indigenous authenticity within communities (Clark et al., 2017a).

The effects and consequences of lateral violence were widely recognized as far-reaching and harmful to wellbeing. An article that employed a mixed-data methodology reported on lateral violence incidents and quantitative measures of psychological distress, which complemented qualitative responses (Clark et al., 2016). Qualitative findings across multiple studies reported feelings of shame, guilt, rejection, and reduced self-esteem as common implications of lateral violence (Bennett, 2014; Monchalin et al., 2020). Relations between suicide and lateral violence within Indigenous communities in Norwegian contexts have been explored. Stoor et al. (2019) proposed a framework for conceptualizing cultural meanings of suicide within Sámi communities. The framework depicted a bidirectional influence between compromised problem-solving strategies and overwhelming adverse challenges experienced by Sámi peoples. Systemic, relational, and cultural factors (e.g., cultural values for self-sufficiency) were discussed as variables that may jeopardize problem-solving mechanisms relating to suicide. Overwhelming adverse challenges experienced by Sámi peoples included cultural losses from Norwegianization, racism and discrimination, and incidents of lateral violence. What was apparent across all studies reviewed in this SLR was that lateral violence within Indigenous communities is prevalent, largely covert, and associated with adverse experiences.

Awareness and Terminology

The application of the term “lateral violence” within the context of Indigenous communities has only been a relatively recent adoption. The term has been widely used in the nursing industry to describe horizontal aggression between members of the profession (e.g., Roberts et al., 2009). In recognition of the relatively recent inclusion of the term in academic and cultural discourse, many reviewed articles examined participants’ recognition and terminology for the concept. Five articles published by Clark and colleagues (Clark, 2015; Clark et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2017c) investigated awareness and terminology used to describe lateral violence within Indigenous communities in Adelaide, Australia. Overall, familiarity with lateral violence as a concept was common. A questionnaire that surveyed participants before, immediately after, and three months post an educational workshop about lateral violence reported significant agreement among participants in recognizing the presence and impact of lateral violence at many levels of analysis, including at the individual-level, within workplaces, and in the community (Clark et al., 2017b). One of the reported outcomes of this workshop was an increased awareness of lateral violence forms, including recognition of dual roles: (a) personal victimization and (b) ownership of inflicting lateral violence on others (Clark et al., 2017c). In contrast, research conducted in Manitoba, Canada, reported that lateral microaggressions (i.e., a stressor that is a subtle form of discrimination negatively impacting racialized and marginalized peoples [Lui & Quezada, 2019]) were not always acknowledged when witnessed (Van Bewer et al., 2021). Such discoveries prompted the Canadian-based researchers to recommend lateral violence awareness initiatives in their discussion.

Some findings suggest that the term “lateral violence” did not garner unanimous endorsement. Some participants worried that the term carried a negative connotation by potentially promoting an inappropriate emphasis on effects rather than the cause (i.e., colonialism and systemic oppression) and did not accurately capture the entire concept (Clark, 2015). These voiced concerns touch on the valid sensitivity and historical complexity of this topic. Additionally, some thought the inclusion of the word “violence” might only be associated with physical rather than emotional harm (Clark, 2015). However, with these exceptions in mind, most participants seemed to endorse “lateral violence” as an appropriate term to describe the phenomenon and personal experiences.

Other lines of research have examined language of the concept in Canadian contexts (Bailey, 2020). The metaphor of crabs in a bucket (i.e., pulling each other down) was commonly referenced across reviewed articles (Bailey, 2020; Clark, 2015; Clark et al., 2017c). A notable theme across interviews was that having access to a label that facilitates articulation of difficult relatable experiences brought relief, empowerment, hope for social change, and facilitated discussion within communities (Clark, 2015). Some participants recommended the inclusion of a positive contrasting term to accompany lateral violence, such as “lateral love”, “lateral healing”, or “lateral respect” (Clark, 2015). Recommendations such as these may help maintain a balanced use of terminology to describe relations within Indigenous communities.

Communities

Lateral violence may be a difficult, controversial, and taboo topic. Research has revealed lateral violence incidents have resulted in being silenced, normalized, and disputed within some Indigenous communities (Clark et al., 2017c). The bystander effect and defensive coping were discussed as potential contributing factors to the complexity of the topic (Clark et al., 2017c). Mellor (2004) has described defensive coping with racism to include self-protecting and survival responses such as withdrawal, avoidance, cognitive reinterpretation, and denial. To address this challenge respectfully and sensitively, researchers offered confidentiality through pseudonyms for participants to promote open and honest responses (Bennett, 2014; Clark, 2015; Clark et al., 2016, 2017a; Stoor et al., 2019; Van Bewer et al., 2021). In addition to this ethical and moral consideration, the willingness and bravery of participants to openly discuss the issue was commendable and acknowledged by the authors of reviewed studies (e.g., Clark et al., 2017c).

Lateral violence has had detrimental impacts on community connection. In one study, some participants disclosed coping with lateral violence by avoiding or removing themselves from Indigenous groups or settings (Clark et al., 2017a). Further, Bennett (2014) discussed that knowledge of negative lateral violence experiences might deter some Indigenous Peoples from claiming status or attempting to connect with their culture and heritage. Findings also described strengths and successful efforts to combat lateral violence within communities. Elders were described as positive role models, which in turn inspired participants to want to model non-aggressive community relationships for younger generations (Clark et al., 2017a).

Institutions and Workplaces

Apart from lateral violence occurring within communities, two other widespread spaces in which such experiences occurred were within institutions and workplaces. Institutional policies and spaces dedicated to Indigenous students, for example, often homogenize the group and disrespect diversity between and within Indigenous communities (Bailey, 2020). In addition to a lack of inclusivity within shared spaces, Indigenous students reported experiences of being denied student-run Indigenous services due to conflicts (Bailey, 2020). As described by the researcher who reported these findings, such institutional practices advantaged some and disadvantaged others, which has the capacity to contribute to conflict between groups of Indigenous students. It is conceivable that institutional homogenization of Indigenous Peoples possibly impacts lateral violence beyond the education sector. Other researchers found evidence of lateral violence occurring within institutions in the health sector (Monchalin et al., 2020; Van Bewer et al., 2021). Additionally, scarcity effects from limited governmental resources were discussed as playing an impactful role in lateral violence (Clark et al., 2016). The power of the legal system in producing policies and legislation that may influence the reduction of lateral violence, such as anti-bullying and harassment laws, was also covered in the literature (Clark et al., 2017a).

Workplace contexts were prominently explored within the reviewed literature. In one study, many participants first heard of the term “lateral violence” from a workplace: the same setting where high incidents of lateral violence reportedly occurred (Clark, 2015). Research suggests that workplace support and lateral violence policies are lacking for both victims and senior-level staff attempting to ameliorate workplace environments and safety (Clark et al., 2017c). An observed obstacle for intervention was non-Indigenous, senior-level staff’s common “hands-off” approach (Clark et al., 2017c, p. 60). It was concluded that Indigenous and non-Indigenous employees would likely benefit from educational lateral violence workshops to learn more about the issue and increase cultural competency (Clark et al., 2017a, 2017c).

Identities

Indigenous Identities

One manifestation of lateral violence prevalent across many studies and pertinent to Indigenous identity was questioning the authenticity of Indigeneity. Some interviewed Indigenous participants acknowledged holding internal racist beliefs and negative stereotypes of Indigenous Peoples themselves (Bennett, 2014). Conflicts between groups were often based on perceptions of “true” Indigeneity based on factors such as appearance, blood quantum, living on reserves versus urban areas, and degree of involvement in traditional cultural practices versus alignment with non-Indigenous or White values (Bailey, 2020; Clark et al., 2016). Experiences questioning the authenticity of Indigeneity among Métis women was another demonstration of lateral violence. This may also be an example of bloodism (Monchalin et al., 2020)—a term used to describe discrimination based on blood quantum stemming from colonial classification systems (Middleton-Moz, 1999, as cited in Aboriginal Healing Foundation, 2005). Some Indigenous service providers did not acknowledge Métis women as Indigenous (Monchalin et al., 2020). Similar patterns were reported in Van Bewer et al. (2021) research, which utilized a forum theatre methodology to explore inequitable experiences among Indigenous female health care workers and students. Not all participants playing the role of forum theatre audience members identified lateral violence in a vignette that portrayed a Métis woman’s Indigenous identity being questioned (Van Bewer et al., 2021). Some audience members claimed that the Métis woman was engaging in cultural appropriation by wearing traditional earrings and concluded her behavior to be offensive to the other Indigenous woman in the vignette (Van Bewer et al., 2021). In contrast, finding strength and meaning in Indigenous identity was a reported protective factor against lateral violence for some participants (Clark et al., 2017a).

Another relevant thread within the literature was discrimination based on skin color. Bennett (2014) aimed to share the stories of racism and lateral violence among lighter-skinned Indigenous participants in Australia and how these experiences impacted cultural identity concepts. Participants in this study reported that being lighter-skinned was a social disadvantage and hoped for greater inclusivity of diverse Indigenous identities to be considered within their communities, regardless of appearance (Bennett, 2014). Another study described light-skin privilege experienced in health care contexts accompanied by feelings of guilt for passing as White (Monchalin et al., 2020). Other authors explained that passing as White was suggestive of being a traitor within some Indigenous communities (Clark et al., 2016). There was also recognition that darker-skinned Indigenous Peoples also experienced lateral violence (Clark et al., 2016).

Women

With respect to the reasons for de-identifying participants’ qualitative responses in the literature, it made distinguishing between Indigenous women’s and men’s experiences somewhat more challenging. Rather than assuming gender based on pseudonyms, only statements explicitly described as being from Indigenous women were categorized as such during this SLR. Of the ten reviewed articles in this SLR, it was possible to distinguish between Indigenous women’s and men’s lateral violence experiences in three articles following this protocol. The first of these three studies only sampled Métis women (Monchalin et al., 2020). The authors justified this gender-based criterion due to observed gender-based disparities. Findings suggested Indigenous women accessing and working within Indigenous-based health services were bullied, gossiped about, and were made to feel unwelcomed.

The second study only sampled Indigenous and non-Indigenous women (Van Bewer et al., 2021). The authors presented only sampling women as a potential study limitation but rationalized that the majority of the nurse and non-nurse health care worker and student population sampled was female. Issues relating to identity navigation and disclosure were reported as particularly challenging for women who self-identified as Métis. Appearance was another factor linked to identity navigation and disclosure.

The third study was conducted by Bailey (2020) and interviewed Indigenous post-secondary students. Indigenous female students shared needing to take leaves of absence from cumulative stress, to which lateral violence contributed (Bailey, 2020). Another experience of lateral violence endured by an Indigenous woman was a lack of compassion for grieving a loved one’s death when a cultural 10-day grieving custom was disrespected. The author commented on an apparent dissonance between a female participant’s recognition of the role of colonization while simultaneously attributing lateral violence to a characteristic behavior of Indigenous Peoples. This paradox speaks to the complexity of the impacts of colonization. Notably, an Indigenous woman commented that “people forget we’re trying to fight the fight together and not against each other” (Bailey, 2020, p. 1043).

Non-Indigenous

Nearly all of the articles reviewed in this SLR explored the role and impact of non-Indigenous individuals on lateral violence within Indigenous communities. Interviews with Indigenous students suggested that non-Indigenous students may play an ongoing role in fueling lateral violence within universities by making racist and discriminatory comments about Indigenous cultures (Bailey, 2020). The role of non-Indigenous individuals fueling lateral violence was similarly discussed in an article by Clark et al. (2016). Participants suggested connections between White individuals and institutions and lateral violence as a “divide and conquer” technique (Clark et al., 2016, p. 47). Still, there were instances reported where non-Indigenous individuals were valued as allies in addressing lateral violence. Participants indicated that the involvement of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals in the education process of addressing lateral violence was helpful as it combined both bonded and bridging supports, respectively (Clark et al., 2017a).

Resilience, Resistance, and Interventions

The social harms and psychological distress associated with lateral violence were made clear across all reviewed articles. Evidence about current resilience, coping mechanisms, and resistance was also presented. Strategies to challenge lateral violence included decolonization efforts, connecting with cultural identity, utilizing social support systems, protective avoidance, positive reinterpretation, self-reflection, and choosing not to engage or confront witnessed lateral violence incidents (Bailey, 2020; Clark et al., 2017a). Recommended actions to reduce lateral violence further were outlined by the authors reviewed in this SLR. Suggestions included promoting the empowerment and resilience of Indigenous Peoples, increasing awareness of the role that colonial practices have on contributing to internalized oppression, and making serious efforts to decolonize and value Indigenous Ways of Knowing and being (Bailey, 2020).

Increasing awareness and labeling lateral violence was reported as an empowering step in community healing by some participants (Clark et al., 2017a). Participants recommended campaigning efforts and the use of media to raise awareness about lateral violence and involving youth in lateral violence education (Clark et al., 2017a) advocated increased mobilization of education (e.g., workshops) on lateral violence to help unify communities. Another study supported the value of education to discourage racism and incidents of lateral violence. Bennett (2014) reported that education to raise awareness about lateral violence seemed to reduce incidents of Indigenous participants having to explain or justify their own identity to both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples alike. Further, calls to raise awareness about lateral violence incidents were also put forth by Van Bewer et al. (2021). Clark et al., 2017b assessed the effectiveness of a one-day lateral violence awareness workshop that they developed and found it to be associated with positive outcomes immediately after and three months post-participation.

Discussion

This SLR overviewed the present state of the study of lateral violence within Indigenous communities. Current scholarship in this area suggests that lateral violence is common, often indirect, and frequently accompanied by deleterious outcomes. This form of intragroup identity-based oppression is recognized as a destructive ramification of colonialism. A prevalent display of lateral violence disclosed within the literature was the questioning of Indigeneity, which was regularly attributed to identity-based factors such as appearance (e.g., skin pigmentation; Bennett, 2014; Clark et al., 2016) and ancestry (e.g., Métis; Monchalin et al., 2020; Van Bewer et al., 2021). Experiences of lateral violence have reportedly deterred navigation and reclamation of cultural identity and threatened the sense of belonging within communities. This act of othering may be a reiteration of the “us” versus “them” phenomenon described within post-colonial theory (Saada, 2014).

Lateral violence occurring within Indigenous communities seems to be complicated by the contentious nature of the topic. Reviewed findings suggest that intragroup conflict and oppression may be normalized or silenced within some communities, institutions, and workplaces (e.g., Clark et al., 2017c). The forbidden and controversial nature of lateral violence may be an added challenge in seeking to understand and facilitate healing journeys related to lateral violence experiences. From a theoretical standpoint, both intersectionality and post-colonial theory maintain that analysis from a systemic perspective, which examines the historical and contemporary role of power dynamics and institutions is crucial. Initiatives supporting decolonization and the principles of reflexivity and restoration were recommended for Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities and organizations.

Fast & Richardson (2019) have expressed a contrasting perspective of lateral violence. They have critiqued the concept and contend that all violence is unilateral and cannot be mutual. In addition, they posit that within a violent relationship, there exists a clear distinction between the role of the perpetrator and the victim. Further, Fast & Richardson (2019) argue that labeling intragroup conflict within Indigenous communities as lateral violence is a form of victim-blaming: “attention to so-called lateral violence (violence within a group) is one of the successful strategies used by those in power to discredit the ability of Indigenous People to live harmoniously in their communities without paternalistic intervention” (p. 9). Likewise, the conceptual acceptability of intragroup microaggressions has been questioned (Sue, 2010, as cited in Van Bewer et al., 2021). However, by denying the existence of this form of violence, such perspectives may unintentionally be silencing and invalidating lived experiences shared by Indigenous Peoples. While recognizing that lateral violence is a controversial or taboo topic for some, we disagree with the viewpoint that lateral violence is a belittling concept. Importantly, the reviewed literature in this SLR found evidence of resilience present within communities in addressing lateral violence. We appreciate the need for research to also account for the strong, positive interpersonal interactions and relationships within Indigenous communities. Similar proposals have been suggested by participants reviewed within this SLR through promoting the need for additional terms such as “lateral love” and “lateral respect” (Clark, 2015).

Methodological Considerations

The ten studies reviewed in this SLR have each contributed to the limited available research on lateral violence within Indigenous communities. Notably, many of the researchers explicitly stated to have employed either an Indigenous framework or Two-Eyed Seeing approach within their methodology (Bennett, 2014; Clark, 2015; Clark et al., 2016, 2017a, 2017b, 2017c; Monchalin et al., 2020; Van Bewer et al., 2021). These frameworks counter the dominance of Western epistemologies and the silencing of Indigenous Ways of Knowing, which have been systemically oppressed throughout history. Research promoting the coexistence of knowledge systems is enriched by the strengths of involved worldviews (Reid et al., 2021). Hence, methodologies that operate from a position of knowledge coexistence support post-colonial efforts. Another methodological strength within this body of research was the effort to represent diversity within Indigenous communities, such as the inclusion of Métis participants (e.g., Monchalin et al., 2020) and participants from varied occupational positions (e.g., Stoor et al., 2019).

Common limitations reported within the reviewed literature included small sample sizes, which may have limited generalizability of findings, along with potential selection and recruitment biases. However, as noted by Stoor et al. (2019) and others (Vasileiou et al., 2018), data saturation is often prioritized over sample size per se in qualitative research. Additionally, factor analysis of the lateral violence workshop questionnaire developed and administered by Clark et al., 2017b did not indicate any clear underlying factors. This limitation suggests a need for further development in the quantitative measurement of this concept.

Implications and Directions for Future Research

The reviewed articles have a variety of implications for academia and Indigenous communities around the world (see Table 3). Firstly, the limited number of articles found shows that there is inadequate research on lateral violence among Indigenous Peoples, especially women. Most of the literature was rooted in an Australian context, with only a few of the articles being Canadian (Bailey, 2020; Clark et al., 2017c; Monchalin et al., 2020). Because of the limited amount of research, the results from the various studies cannot be generalized to a broader population. Again, this shows the dire need for more research surrounding this important topic. Some of the articles referred to lateral violence studies that were done in the nursing profession and encouraged future research to be extended to the Indigenous population (Clark et al., 2016; Bailey, 2020).

Table 3.

Summary of Implications.

| Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research | |

|---|---|

| Practice | • Reviewed findings indicate a demand for the continued development, dissemination, and evaluation of public awareness initiatives and curricula |

| • Lateral violence intervention and disruption strategies at the individual, community, and systemic level are justified. Preliminary evidence has suggested that workshops may be an effective medium for social change and empowerment within communities and workplaces | |

| Policy | • Reforming policy to support culturally safe institutional spaces that respect diversity is necessary |

| • Cultural competency and unconscious bias training may improve service delivery and outcomes | |

| Research | • Further investigations into lateral violence within Indigenous communities is warranted. In particular, future research with samples of Indigenous women may offer valuable insights |

| • The development of a culturally informed measure of lateral violence within Indigenous communities may offer quantitative data and be used to measure the effectiveness of intervention programming | |

Secondly, almost all the reviewed articles urge funding service agencies to provide improved services for Indigenous People, whether that be in schools, mental health, physical health, or safety (Bailey, 2020; Monchalin et al., 2020). The reviewed articles can educate teachers, social workers, health care workers, or anyone in public service on how to better work in collaboration with Indigenous Peoples while holding the principles of respect and kindness. As found in the reviewed articles, many Indigenous People are discriminated against because of their race and appearance. It was also found that Indigenous Peoples were often asked what percentage they were Indigenous and questioned about their ethnic identity (Monchalin et al., 2020). Providing the public with better education, especially focusing on anti-racism education (Bennett, 2014), would likely lead to improved health care and inclusion and reduced racism towards Indigenous Peoples.

There are many possibilities for future directions in this area of study. Of the utmost importance is the general expansion of both qualitative and quantitative research on lateral violence to include Indigenous Peoples and in particular Indigenous women, as there is a clear gap in the literature. Another consideration is the study of Indigenous People’s experience of lateral violence within intersecting identities. For example, during the process of this SLR, we found many studies researching lateral violence among nurses (e.g., Bailey, 2020), but rarely studies of Indigenous Peoples who are nurses as well. Indigenous People in the nursing profession may experience lateral violence within their own community as well as within their profession, placing them at a much higher risk for experiencing lateral violence.

Overall, and in line with the work of Clark et al. (2016), further investigation into the prevalence of lateral violence within Indigenous communities is essential. Building on the work of Bennett (2014), future studies could also aim to explore lateral violence towards Indigenous Peoples from diverse communities across the globe to determine the cross-cultural similarities and differences in people’s experiences of lateral violence. Taken together, it is clear from this SLR that much more research on lateral violence among Indigenous People, especially Indigenous women, is needed, whether that be replicating previous studies in different Indigenous communities and areas or designing innovative studies that study lateral violence. The expansion of research in this area is critical to gaining a more comprehensive understanding of Indigenous People’s experiences of lateral violence, raising awareness within Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, and addressing lateral violence. If people were to speak more openly about lateral violence, there would be better recognition of when lateral violence was occurring, which would allow for greater opportunities for prevention and intervention efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

Given that lateral violence among Indigenous women is a scarcely researched social concern, a strength of this SLR was the comprehensive, systematic method employed in searching, screening, and synthesizing the literature on this topic. Presenting the themes that emerged throughout this body of literature into a coherent whole may serve as a footing for future research to enrich our understanding of lateral violence and inform policy and practice initiatives to disrupt this wounding pattern of historical oppression.

Potential limitations or critiques of this SLR might include the inclusion of a gender criterion, exclusion of gray literature, and differences in terminology. Additionally, three of the ten reviewed articles authored by Clark and colleagues analyzed data from one sample (Clark, 2015; Clark et al., 2016, 2017a). Some academics have advocated for the inclusion of Indigenous men in research investigating intragroup victimization/survivorship within Indigenous communities. As argued by Hansen & Dim (2019): “the distinction between the violence Indigenous women and men are involved with is so similar that it warrants Indigenous men’s inclusion rather than their exclusion” (p. 6). We respect this sentiment and acknowledge that support for this view may be further explored within an intersectional framework. As previously discussed within the introduction of this SLR, we recognize that Indigenous women’s experiences with lateral violence may be similar, additive, or specific to the experiences of other gender identities within Indigenous communities also impacted by colonialism. The theorized additive layer of patriarchal systems, which may affect the experiences of Indigenous women, informed the rationale for the gender criterion in this SLR. Accordingly, the intersecting social positions inhabited by Indigenous women and the institutional barriers they endure have been referred to as triple jeopardy or discrimination (Croce, 2020; Gerber, 2014).

Another potential limitation of this SLR was the eligibility requirement, which stipulated that chosen articles had to be peer-reviewed to satisfy inclusion criteria. Therefore, this criterion excluded gray literature, including brochures, webpages, and other non-peer-reviewed media that have communicated information about lateral violence within Indigenous communities—many of which have been authored or created by Indigenous organizations and groups.

Lastly, varying terminology used within the field to describe interpersonal aggression may have limited which articles met eligibility requirements for this SLR. Although lateral violence has been operationally defined as both overt and covert interpersonal aggression between members of an oppressed group, most behaviors reported in the ten reviewed articles referred to covert forms of lateral violence within Indigenous communities. The limited reports of overt lateral violence within the reviewed literature may have to do with the different language used to discuss violence and aggression between Indigenous community members. For example, research exploring family violence or intimate partner violence within Indigenous communities may not use the term “lateral violence” when disseminating their findings.

Author Biographies

Lindsey Jaber, PhD, C. Psych, is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Windsor. She is a registered School, Clinical, and Counseling Psychologist with the College of Psychologists of Ontario. Her professional and scholarly experience working in schools, community settings, and private practice has informed her research. Dr. Jaber has many refereed publications and conference presentations on topics including aggression/violence, trauma, mental health, and social/emotional development.

Cynthia Stirbys, PhD, is Saulteaux-Cree from Cowessess First Nation, Treaty 4, Saskatchewan. Her research focuses on intergenerational trauma in the lives of Indigenous women with emphasis on how to strengthen relational ties in support of improving the quality of life for all Indigenous Peoples. Dr. Stirbys is also an Assistant Professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Windsor.

Jesse Scott is an honors student in the Department of Psychology at the University of Windsor. Her research focuses on trauma, violence, and aggression. She is interested in applying research to support risk assessment and management, policy reform, practice and treatment.

Emma Foong is a PhD student in Educational Studies through the joint PhD program at the University of Windsor. Her research focuses on Asian Canadian identity, body image, eating disorders, and mental health. She is interested in how cultural identity informs and shapes body image. She is also passionate about teaching mindful and inclusive language surrounding food and body image.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the University of Windsor research grants for women 820421.

ORCID iDs

Lindsey Jaber https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7384-0420

Jesse Scott https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7424-6092

References

- Aboriginal Healing Foundation (2005). Reclaiming connections: Understanding residential school trauma among Aboriginal people. http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/healing-trauma-web-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Auger M. D. (2016). Cultural continuity as a determinant of Indigenous Peoples’ health: A metasynthesis of qualitative research in Canada and the United States. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 7(4), 3. 10.18584/iipj.2016.7.4.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey K. A. (2020). Indigenous students: Resilient and empowered in the midst of racism and lateral violence. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(6), 1032–1051. 10.1080/01419870.2019.1626015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett B. (2014). How do light-skinned Aboriginal Australians experience racism? AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 10(2), 180-192. 10.1177/117718011401000207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bombay A., Matheson K., Anisman H. (2014). Origins of lateral violence in Aboriginal communities: A preliminary study of student-to-student abuse in residential schools. Aboriginal Healing Foundation. https://www.ahf.ca/downloads/lateral-violence-english.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette C. (2015). Historical oppression and intimate partner violence experienced by Indigenous women in the United States: Understanding connections. Social Service Review, 89(3), 531-563. 10.1086/683336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Y. (2015). What’s in a name? Lateral violence within the Aboriginal community in Adelaide, South Australia. The Australian Community Psychologist, 27(2), 19-34. https://groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/ACP-27-2-2015-ClarkandAugoustinos.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Y., Augoustinos M., Malin M. (2016). Lateral violence within the Aboriginal community of Adelaide: “It affects our identity and wellbeing”. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri-Pimatisiwin, 1(1), 43-52. https://journalindigenouswellbeing.com/media/2018/07/35.28.Lateral-violence-within-the-Aboriginal-community-in-Adelaide-“It-affects-our-identity-and-wellbeing”.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Y., Augoustinos M., Malin M. (2017. a). Coping and preventing lateral violence in the Aboriginal community in Adelaide. The Australian Community Psychologist, 28(2), 105-122. https://groups.psychology.org.au/Assets/Files/ACP-Vol28-Issue2-2017-Clark.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Y., Augoustinos M., Malin M. (2017. b). Evaluation of the preventing lateral violence workshop in Adelaide, South Australia: Phase one quantitative responses. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri-Pimatisiwin, 2(3), 54-66. https://journalindigenouswellbeing.com/media/2018/07/86.83.Evaluation-of-the-preventing-lateral-violence-workshop-in-Adelaide-South-Australia-Phase-one-survey-responses.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Clark Y., Augoustinos M., Malin M. (2017. c). Evaluation of the preventing lateral violence workshop in Adelaide, South Australia: Phase two qualitative aspect. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri-Pimatisiwin, 2(3), 54-66. https://journalindigenouswellbeing.com/media/2018/07/87.84.Evaluation-of-the-preventing-lateral-violence-workshop-in-Adelaide-South-Australia-Phase-two-qualitative-aspects.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cole E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64(3), 170–180. 10.1037/a0014564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper E., Driedger S. M. (2019). “If you fall down, you get back up”: Creating a space for testimony and witnessing by urban Indigenous women and girls. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 10(1), 1. 10.18584/iipj.2019.10.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 538-554. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclfhttp://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8. [Google Scholar]

- Croce F. (2020). Indigenous women entrepreneurship: Analysis of a promising research theme at the intersection of Indigenous entrepreneurship and women entrepreneurship. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(6), 1013-1031. 10.1080/01419870.2019.1630659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fast E., Richardson C. (2019). Victim-blaming and the crisis of representation in the violence prevention field. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 10(1), 3–25. 10.18357/ijcyfs101201918804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S. L., Hordyk S. R., Etok N., Weetaltuk C. (2019). Exploring community mobilization in Northern Quebec: Motivators, challenges, and resilience in action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 159–171. 10.1002/ajcp.12384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber L. M. (2014). Education, employment and income polarization among Aboriginal men and women in Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 46(1), 121-144. 10.1353/ces.2014.0015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanka P. R. (2020). From buzzword to critical psychology: An invitation to take intersectionality seriously. Women & Therapy, 43(3–4), 244–261. 10.1080/02703149.2020.1729473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J. G., Dim E. E. (2019). Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous People and the imperative for a more inclusive perspective. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 10(1), 2. 10.18584/iipj.2019.10.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M., Lee E. (2021). Epistemic injustice and Indigenous women: Toward centering indigeneity in social work. Affilia - Journal of Women and Social Work, 36(1), 088610992098526. 10.1177/0886109920985265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lui P. P., Quezada L. (2019). Associations between microaggression and adjustment outcomes: A meta-analytic and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(1), 45–78. 10.1037/bul0000172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marecek J. (2016). Invited reflection: Intersectionality theory and feminist psychology. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(2), 177–181. 10.1177/0361684316641090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellor D. (2004). Responses to racism: A taxonomy of coping styles used by Aboriginal Australians. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(1), 56–71. 10.1037/0002-9432.74.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton-Moz J. (1999). Boiling point: The high cost of unhealthy anger to individuals and society. Health Communications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monchalin R., Smylie J., Nowgesic E. (2020). “I guess I shouldn’t come back here”: Racism and discrimination as a barrier to accessing health and social services for urban Métis women in Toronto, Canada. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 7(2), 251–261. 10.1007/s40615-019-00653-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Native Women’s Association of Canada (2015). Aboriginal lateral violence (pp. 1–6). https://www.nwac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2011-Aboriginal-Lateral-Violence.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. B., Harding K. J. (2011). Post-colonial theory and action research. Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry, 2(2), 1–6. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tojqi/issue/21391/229347 [Google Scholar]

- Reid A. J., Eckert L. E., Lane J. F., Young N., Hinch S. G., Darimont C. T., Cooke S. J., Ban N. C., Marshall A. (2021). “Two-eyed seeing”: An Indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish and Fisheries, 22(2), 243-261. 10.1111/faf.12516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S. J., Demarco R., Griffin M. (2009). The effect of oppressed group behaviours on the culture of the nursing workplace: A review of the evidence and interventions for change. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(3), 288–293. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2008.00959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada N. L. (2014). The use of postcolonial theory in social studies education: Some implications. Journal of International Social Studies, 4(1), 103–113. https://iajiss.org/index.php/iajiss/article/view/119 [Google Scholar]

- Samuels G. M., Ross-Sheriff F. (2008). Identity, oppression, and power: Feminisms and intersectionality theory. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 23(1), 5–9. 10.1177/0886109907310475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseer L., Moher D., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., Shekelle P., Stewart L. A., Altman D. G., Booth A., Chan A. W., Chang S., Clifford T., Dickersin K., Egger M., Gøtzsche P. C., Grimshaw J. M., Groves T., Helfand M., Whitlock E. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ, 350(7989), g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbys C. D. (2016). Potentializing wellness through the stories of female survivors and descendants of Indian residential schools: A grounded theory study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Ottawa].

- Stoor J. P. A., Berntsen G., Hjelmeland H., Silviken A. (2019). “If you do not birget [manage] then you don’t belong here”: A qualitative focus group study on the cultural meanings of suicide among Indigenous Sámi in arctic Norway. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 78(1), 1565861. 10.1080/22423982.2019.1565861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bewer V., Woodgate R. L., Martin D., Deer F. (2021). Illuminating Indigenous health care provider stories through forum theater. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(1), 61-70. 10.1177/1177180121995801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileiou K., Barnett J., Thorpe S., Young T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 148. 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham M. (2013). Critical choices: Rural women, violence and homelessness. http://domesticpeace.ca/images/uploads/documents/CriticalChoicesRuralWomenViolenceandHomelessnessFinal2013_000.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. (2004). Living well: Aboriginal women, cultural identity and wellness. Prairie Women’s Health Centre of Excellence. [Google Scholar]