Abstract

Child sexual abuse is a public health problem of global magnitude with profound and negative consequences for the victims and society. Thus, psychological intervention with individuals who sexually offended against children is crucial for reducing recidivism. Numerous reviews and meta-analyses have shown the effectiveness of psychological interventions in individuals who sexually offended, but few reviews have been done on this subtype of offenders. This article reviews evaluation studies of intervention programs designed to treat individuals who sexually offended against children, providing a more detailed account of treatment procedures. Articles were identified from peer-reviewed databases, bibliographies, and experts. Following full-text review, 12 studies were selected for inclusion by meeting the following criteria: quantitative or qualitative research studies published in English from 2000 to 2020 with titles or abstracts that indicated a focus on treatment effectiveness, detailing the psychological treatment procedures on adult, male individuals convicted for child sexual abuse. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with a relapse prevention approach was the most frequent modality found in child sexual offending treatment. Besides, different criminogenic and non-criminogenic factors emerge as targets for intervention. Study design, study quality, and intervention procedures shortened the accumulation of evidence in treatment effectiveness.

Keywords: child sexual offending, treatment effectiveness, systematic review, psychological intervention

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a public health problem of global magnitude. Along with the high prevalence of this problem, the literature has shown its profound and negative consequences for the victims and society (Hailes et al., 2019; Wurtele, 2016). The CSA concept encompasses a broad spectrum of behaviors, from acts with physical contact between the perpetrator and the victim to deeds without direct touch between them (e.g., create/distribute sexually abusive images) (Wurtele, 2016).

The topic of child sexual abuse generally elicits fear from the public and a set of negative attitudes towards the perpetrators of type of crime (Church et al., 2011; Harper et al., 2017; Willis et al., 2013). Therefore, the societal negativity about this group has led to a tendency for criminal policies to be punitive (i.e., focused on containment and monitoring) rather than rehabilitative (Church et al., 2011). However, such policies revealed a negative impact on recidivism rates (Bouffard & Askew, 2019; Grossi, 2017). For example, the use of the sex offender registration and notification law is one of the punitive policies that showed a poor relationship to lower the rates of sexual offending (Bouffard & Askew, 2019; Grossi, 2017). Therefore, psychological intervention with this group of individuals is crucial because external prohibitions are, in some cases, opposite to the goal of reducing recidivism and are time-limited (Flinton et al., 2010).

Over the years, the modalities of psychological intervention have changed from a more behavioral approach to a cognitive-behavioral one (Marshall & Hollin, 2015W. L. Marshall & Hollin, 2015). The behavioral approaches see deviant sexual behavior as a distorted manifestation of sexual desire resulting from conditioned behavior (Jennings & Deming, 2013; McGuire et al., 1964). This approach is focused in reducing deviant sexual interests using conditioning procedures. The therapy procedure most often used was aversion therapy (Jennings & Deming, 2013). The idea that these techniques were too simplistic, providing little relevance to thoughts and emotions, lead to the development of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Brown, 2005). CBT is a form of psychological treatment that intends to change problematic or dysfunctional behavior by addressing the interaction between emotions, behavior, and thoughts. The shift for a cognitive-behavioral approach had more to do with the shift in the conceptualization of human behavior than to do with the empirical results of this approach (Laws & Marshall, 2003).

In the 1980s, the inclusion of the relapse prevention (RP) model to CBT proved to be a major contribution in this field. This component was intended originally to deal with addictive behaviors and was based on the premise that lapses are a possible part of the process of change (Laws, 2003). In the sexual offending field, RP model aims to assist individuals to identify high-risk situations to reoffend and provides strategies to cope with these situations (Laws & Marshall, 2003). Moreover, RP work is most commonly applied in a way that follows the risk-need-responsivity model (RNR), which has revealed the most robust effect in preventing recidivism rates (Hanson et al., 2009). However, critics argued that RP approaches that follow RNR principles are not sufficiently rehabilitative, since they focus exclusively on risk reduction forgetting the promotion of well-being (Ward & Gannon, 2006; Willis & Ward, 2011). In contrast, the good lives model (GLM) became prominent given its focus on the strengths of individuals (Ward & Stewart, 2003).

Although less expressively and without empirical studies proving its effectiveness with this population, some literature also pointed out the possible advantage of the use of Young’s schema-focused model (Carvalho & Nobre, 2014; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015). Some authors address the relevance of work on patients’ schemas (e.g., Beech et al., 2013; Ó Ciardha & Gannon, 2011), criticizing the superficial approach given to cognitions. A schema may be defined as a cognitive structure comprising dysfunctional memories, emotions, cognitions, and bodily sensations (Young et al., 2003). The schemas once are triggered will then guide information processing to maintain and reinforce the schema, ignoring information schema-inconsistent information and/or selecting schema-consistent information. In the sexual offending field, it would allow gaining greater knowledge about the developmental and cognitive processes involved in sexual offending (Carvalho & Nobre, 2014; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015).

Previous reviews and meta-analyses that include treated individuals who sexually offended against adults and individuals who sexually offended against children revealed that the rate of sexual recidivism among these groups was lower than non-treated individuals who sexually offended (Gannon et al., 2019; Hanson et al., 2002, 2009; Kim et al., 2016; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005; Schmucker & Lösel, 2015). For example, Hanson and colleagues (2002) in one of the most comprehensive meta-analyses to date, conducted a review summarizing data from 43 studies (n = 9454) and showed that the average sexual offense recidivism was 12.3% for treatment groups and 16.8% for comparison groups. Years later, Hanson and colleagues (2009) examined 22 studies, which comprised 3121 treated individuals and 3625 non-treated individuals, and found that the percentage of sexual recidivism among a group of treated individuals who sexually offended was 10.9% against 19.2% of non-treated individuals (Hanson et al., 2009).

Lösel and Schmucker (2005) also analyzed the outcome of 69 treatments (n = 22 181)—including psychological and biological treatments—for individuals who had sexual offenses and found a reduction in sexual recidivism (1.1% treated vs. 17.5% untreated). Schmucker and Lösel (2015) later updated this meta-analysis, restricting the inclusion criteria to research designs with the highest quality. The results revealed that biological treatments did not present the necessary quality to be included in the analysis. However, the psychological intervention proved to be effective (a rate of 10.1% of recidivism in treated individuals against 13.7% for untreated) (Schmucker & Lösel, 2015). More recently, Gannon and colleagues (2019) conducted a meta-analysis comprising 41,476 individuals and found that sexual offense programs produce significant reductions in sexual reoffending rates (9.5% treated vs. 14.1% untreated).

Few systematic reviews have directly assessed treatment effectiveness specifically for individuals who sexually offended against children, and the results are not encouraging (Gronnerod et al., 2015; Langstrom et al., 2013; Walton & Chou, 2015). Langstrom and colleagues (2013) carried out a systematic review of medical and psychological interventions, restricting the inclusion criteria to studies with low to moderate risk of bias. The review analyzed the outcome of eight studies and did not find evidence to confirm that treatment was effective at reducing recidivism (Långström et al., 2013). Two years later, Walton and Chou (2015) conducted a review of psychological intervention with 10 studies (n = 2,119) and concluded that the effectiveness of treatment for this group of individuals remains to be demonstrated. The same was reported by Gronnerod and colleagues (2015) in their attempt to assess the effectiveness of the intervention.

The debate over the effectiveness of psychological interventions for sexual offending remains divided: several authors concluded that treatment reduces recidivism (Hanson et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2016; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005; Mpofu et al., 2018; Tyler et al., 2021), whereas others maintain the idea that there is not enough evidence from studies with high methodological quality, to be certain that treatment works (Ho & Ross, 2012; Rice & Harris, 2003). Many critics pointed out that random controlled design (RCT) is the gold standard for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the programs (Rice & Grant, 2013), yet there are few studies with this design. For example, Langstrom et al. (2013) only found three RCTs and Walton and Chou (2015) found only one RCT.

One of the explanations for this is that RCT design creates numerous ethical and practical problems. It demands that participants are randomly assigned to a treatment group or to a control group, without a therapeutic approach (Rice & Grant, 2013). In this way, some studies either do not have a control group or have one that includes dropouts and refusal participants, which makes the two groups incomparable and compromises the control of the results of treatment effects (Rice & Grant, 2013).

The Collaborative Outcome Data Committee (CODC) (Beech et al., 2007a; Beech et al., 2007b) was formed to define criteria for eliminating these threats to validity. Although these guidelines have a primary concern with recidivism rates for assessing the effectiveness of sexual offending treatment, it is important to know what changes lead individuals to desist from committing sex crimes. In addition, it is highly relevant to know how a program works in a short term. One of the ways of addressing this question involves measuring change on treatment targets (Nunes et al., 2011) and this is a gap in the systematic reviews published in the last years.

Another problem in this field concerns the “one-size-fits-all” standard treatment. Some treatment programs have included individuals with different convictions for sexual crimes, considering this population as a homogeneous group. However, it is essential to know how the reported treatment effects are relevant to specific groups. Also, it is crucial to clarify the topics addressed by the intervention since individuals who sexually offended against children (with or without contact) and against adults have different criminological needs (Joyal et al., 2014; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015; Walton & Chou, 2015). The prevention of sexual crimes as well as the effective management of individuals who sexually offended should be based on the offending specific features and needs (Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015).

The objective of the current study is to identify and analyze the quality of empirical assessments of programs for individuals who sexually offended against children using a structured systematic review. This systematic review builds upon prior literature review examining treatments for child sexual offending by (1) providing a more detailed accounting of treatment procedures, (2) examining how treatment needs were measured, and (3) analyzing the effectiveness of the treatment programs in a short term (pre-post measures) and/or a long term (recidivism rates).

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

The present systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). Although the systematic review was not registered before completion, this predefined protocol was followed.

Studies eligible for inclusion presented the following criteria: (a) studies with individual or group psychological interventions; (b) studies that describe implementation variables of the intervention programs (length of program, topics covered during intervention, and treatment modality); (c) studies that included only adult, male, convicted of child sexual abuse; (d) studies published in peer-reviewed journals; (e) empirical studies (both quantitative and qualitative); and (f) studies written in English. When applicable the outcome measures selected were the official criminal record and/or pre-post changes in the target measures. For a study to be excluded, one or more of the following criteria has to be present: (a) studies that included female or adolescent individuals convicted for child sexual abuse; (b) studies that included mixed sexual crimes (child sexual abuse and rape) without separate statistical analysis; and (c) studies that had drug-based treatments in combination with psychological interventions. In the case of studies that included mixed sexual crimes, we just considered the results of the sample of individuals who have sexually offended children, excluding data regarding the abuse of adults. No restrictions about study design were made due to the lack of research including only child sexual offending.

Information Sources and Search Process

Studies were identified in three electronic databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, and SCOPUS. Searches were performed in December 2020. We used the following equation searching by title, abstract, and keywords for: (treatment or intervention or therapy or program* or psychotherapy) AND (child abuser* OR child sexual abuser* OR child pornograph* OR child molest* OR pedophil* OR paedophil* OR “internet sex* offend*”), that resulted in 35 combinations. Only studies published in 2000 or later were included since some pioneering treatments may now be obsolete (Soldino & Carbonell-Vayá, 2017). In addition, we checked the reference lists of several reviews on the subject.

Study Selection and Data Collection Process

After removing duplicates, abstracts were read, and the papers were selected for full-text analysis by two independent researchers. When discrepancies came up, the authors resolved disagreements through discussion. Any remaining divergence was resolved by a third author.

We developed a data extraction sheet (Table 1 and Table 2) for data collection with the following topics: (a) sample characteristics (age; sample size; index offense); (b) country; (c) design of the study; (d) intervention needs; (e) modality of the program; (f) setting; (g) program duration; (h) theoretical models of the program; (i) targets of treatment; (j) type of outcome; and (k) main findings.

Table 1.

Study design and characteristics of the sample.

| Study | Design | Sample characteristics (age, index offense) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elliott et al., (2019) | Cohort study | N = 690 adult males; mean age 40 (SD = 11.6; range from 18 to 72 years). 84.6% of the sample with an indecent image of children conviction (IIOC); 15.4% of the sample with an IIOC offense combined with either a concurrent index contact/paraphilic sex offense a prior history of contact/paraphilic sexual offenses, or a subsequently detected historical contact/paraphilic sexual post index offense | United Kingdom |

| Mandeville-Norden et al., (2008) | Cohort study | N = 341 males; mean age 45.33 (SD= 14.2; range from range from 18 to 82). Convicted of a sexual offense against a child, which involved some degree of physical contact | United Kingdom |

| Beech et al., (2012) | Cohort study | N = 413 males; mean age = 44.16 (SD = 14.15, range from 18 to 82). Convicted of a sexual offense against a child, which involved some degree of physical contact. | United Kingdom |

| Beech & Ford (2006) | Cohort study | N = 51 males; mean age = 42.2 (SD = 13.6, range from 21 to 66). 80% (n = 41) indecent assault against children, 18% (n=9) gross indecency against a child, 10% (n = 5) buggery, 8% (n = 4) rape of a child, 6% (n = 3) incest, 4% (n = 2) unlawful sexual intercourse, and 2% (n = 1) possession of obscene material | United Kingdom |

| Biddey & Beech (2003) | Cohort study | N = 59 males; mean age 39.5 (SD = 12.6, range from 21 to 75). Offense index: Child sexual abuse | United Kingdom |

| Colton et al., (2009) | Exploratory design | N = 35 adult males; mean age 44; index offense: Child sexual abuse | United Kingdom |

| Dervley et al., (2017) | Descriptive study | N = 13 participants; mean age 47.3 (SD = 10.6). Index offense: n = 10 (76.9%) downloading child sexual exploitation material (CSEM); n = 2 (15.4%) downloading and distributing CSEM; n = 1 (7.7%) incitement and downloading CSEM | United Kingdom |

| Marques et al., (2005) | Randomized controlled trial | N = 704 male offenders; age range between 18 and 60; n = 259 treatment (RP) condition, n = 225 volunteer control (VC) condition, and n = 220 nonvolunteer control (NVC) condition. Each group was 58% child molesters and 22% rapists (with adult victims) | United States |

| Fisher et al., (2000) | Cohort study | N = 74 male; index offense: Child sexual abuse | United Kingdom |

| Middleton et al., (2009) | Cohort study | N = 264; mean age 41.5 (SD = 11.27, range from 19 to 73). Index offense: Child pornography | United Kingdom |

| Serran et al., (2007) | Quasi-experimental study | N = 60 adult males; n = 33 treatment group with mean age 46.45 (SD = 10.52); n = 27 waiting list group with mean age 46.59 (SD = 12.57). Index offense: Child sexual abuse against an unrelated child victim | Canada |

| Craissati et al., (2009) | Cohort study | N = 273 males; index offense: n= 198 child sexual abuse and 75 rapists | United Kingdom |

Table 2.

Summary of therapeutic procedures and outcomes.

| Reference | Treatment program | Treatment type | Intervention format, timing, and setting | Treatment targets | Outcome measures | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beech & Ford (2006) | Wolvercote Programme | CBT + RP | Mixed format; 4 weeks (assessment phase); 2- to 4-week (pre-intervention); 6–12 month, 5 days per week (treatment program); community setting | Acceptance of responsibility; victim empathy; intimacy and sexual module; interpersonal skills; attitudes; self-efficacy; relapse prevention | Pre-post treatment measures (Children and Sex Questionnaire; Victim Empathy Distortions scale; Short Self-Esteem Scale; UCLA Emotional Loneliness Scale; Under-assertiveness/Over-assertiveness Scales; Personal Distress Scale; Nowicki–Strickland Locus of Control Scale) recidivism (reconvictions; 2- and 5-years follow-up period). | Pre-post change: 25% (n =4) high deviance men achieved a treated profiled compared to 48% (n =12) low deviance men. High deviance men: clinically significant change in all of the pro-offending measures for 3 out of 4 treated high deviance and for all of participants on self-esteem, emotional loneliness, and under-assertiveness dimensions; clinically significant decrease in locus of control scale for 2 participants; clinically significant decrease in personal distress scale for 2 participants. Low deviance men: clinically significant decrease in victim empathy distortions scale for 9 participants; clinically significant decrease in emotional identification in children scale for 3 participants; clinically significant decrease in sexual interest in children for 1 participant; clinically significant change on at least three socio-affective scales for 10 participants; clinically significant change on all socio-affective scales for 2 participants and clinically significant change on four of the scales for 2 participants. None of the men who responding to treatment were reconvicted for a sexual offense; 14% who not responding to treatment were reconvicted for sexual offense. |

| Biddey & Beech (2003) | Wolvercote Programme | CBT + RP | Mixed format; 4 weeks (assessment phase); 2- to 4-week (pre-intervention); 6–12 month, 5 days per week (treatment program); community setting | Acceptance of responsibility; victim empathy; intimacy and sexual module; interpersonal skills; attitudes; self-efficacy; and relapse prevention | Pre-post treatment measures (Cognitive Distortions Scale and Victim Distortions Scale) | Approach pathway group: significant reduction in cognitive distortions and victim distortions scale. Avoidant pathway group: no significant pre-post change in both measures. |

| Beech et al., (2012) | Community Sex Offender Groupwork Program Northumbria Sex Offender Groupwork Program Thames Valley Program 1 | CBT + RP | Mixed format; 160–290 hours; community setting | Victim empathy; emotional self-management; intimacy and sexual module; interpersonal skills; attitudes module; risk management and relapse prevention | Recidivism (reconviction; 2-year follow-up and at a 5-year follow-up) | 9% (n=12) “treated” offenders recidivated with sex crimes; 15% (n=20) “untreated” offenders recidivated with sex crimes. |

Note.1These intervention programs were analyzed together; CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy; RP: relapse prevention; MC: model of change; MPIU: model of problematic internet use; GLM: good lives model.

Methodological Quality Analysis

The criteria of the Collaborative Outcome Data Committee to eliminate threats to the validity of studies on intervention for sexual offending are defined to measure only recidivism as an outcome. Considering that we intend to take into account also the short-term changes in individuals and their perception of participation in the programs, we chose to use the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT—version 2018) (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT includes two screening questions and five items for appraising the methodological quality of qualitative studies and different forms of quantitative studies. Each of the criteria is rated as “yes,” “no,” or “can’t tell.” Although the output from the MMAT ranged between 1 and 5, this updated version suggested providing a more detailed presentation of the ratings of each criterion to better information about where the weaknesses of the study reside.

Results

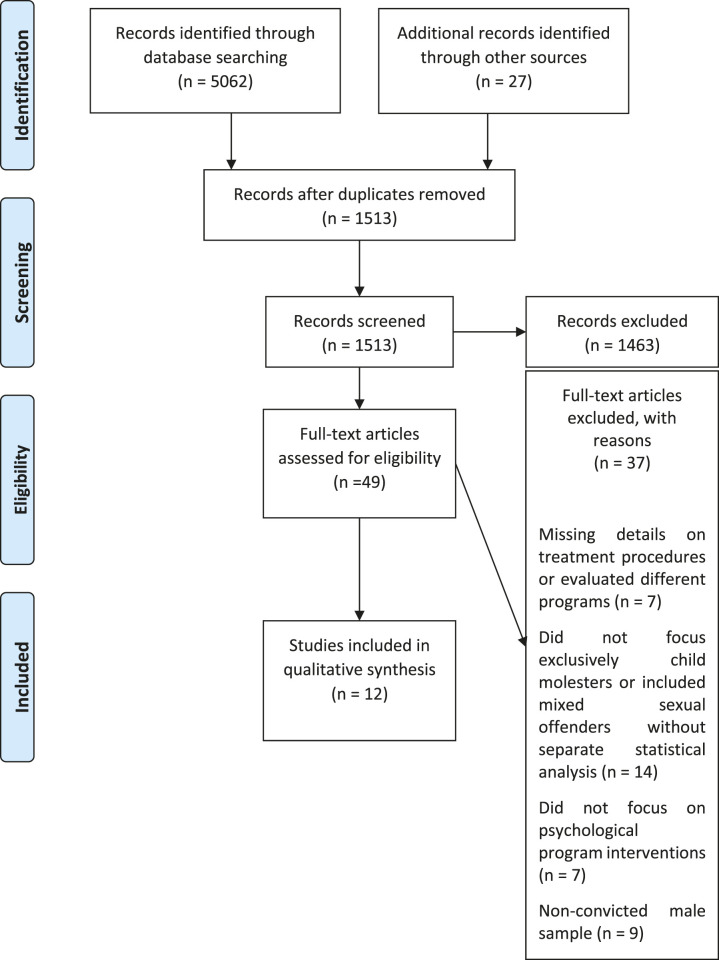

A total of 5062 articles were identified from the search and a further 27 were located from reference checking and expert recommendations. After the removal of duplicates, 1513 were evaluated based on title and abstract and according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full text of 49 articles was retrieved to make a final decision. In the final process, 12 articles were eligible for inclusion, and data were extracted from each one. Figure 1 represents the PRISMA flow diagram displaying the number of studies included in each phase of the selection process, and the reasoning for inclusion/exclusion.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the study selection process.

Quality Assessment

Among the included articles, the following research designs were used: qualitative (n = 2), quantitative non-randomized studies (n = 9), and quantitative randomized controlled trials (RCT) (n = 1).

Of the 12 studies, three studies showed all criteria of excellent (Colton et al., 2009; Craissati et al., 2009; Dervley et al., 2017), one presented four out of five criteria of excellent (Marques et al., 2005), and three showed three out of five criteria (Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Elliott et al., 2019). The remaining five studies did not show an acceptable quality and low risk of bias, with one study meeting only two criteria (Fisher et al., 2000), and four studies presenting only one criterion (Beech et al., 2012; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007).

When analyzing the limitations of the included studies based on the MMAT criteria, seven out of 12 studies failed to include a representative sample of the population or did not account for the confounder for the analysis. Moreover, six studies did not use appropriate instruments regarding the outcome and five studies did not attain complete outcome data.

Characteristics of Studies Included Sample Characteristics

Quantitative Studies

The sample size across all the quantitative studies ranged from 51 (Beech & Ford, 2006) to 704 individuals (Marques et al., 2005). The average age from the participants among the studies varied from 39.50 to 46.59 years. Three studies did not report the average age (Craissati et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2000; Marques et al., 2005).

The majority of the studies examined the effects of treatment on samples of individuals who sexually offended against children with contact (Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Serran et al., 2007) and one study refer to a sample of individuals who sexually offended against children without contact (child pornography) (Middleton et al., 2009). The samples of the remaining four studies were heterogeneous: two studies with individuals convicted for mixed child sexual crimes (Beech & Ford, 2006; Elliott et al., 2019) and two studies with individuals who sexually offended against children and against adults (Craissati et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2005).

Almost all studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009). One study was conducted in the United States (Marques et al., 2005) and another in Canada (Serran et al., 2007).

Qualitative Studies

The sample size of the qualitative studies ranged between 13 (Dervley et al., 2017) to 35 adult males (Colton et al., 2009), and the average age was from 44 to 47.3 years. One study used a sample of people convicted for child sexual abuse (Colton et al., 2009) and another of individuals who had a child pornography conviction (Dervley et al., 2017). These two studies were conducted in the United Kingdom.

Treatment Procedures

Intervention Descriptors

An analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies will be carried out simultaneously to allow a better understanding of the intervention targets. The studies included in this review examined ten treatment programs (k). Five treatment programs were used more than once in the following studies: Community Sex Offender Groupwork Program (Beech et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008), Northumbria Sex Offender Groupwork Program (Beech et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008), Thames Valley Program (Beech et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008), Wolvercote Programme (Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003), and Sex Offender Treatment Programme (Colton et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2000). In addition, three of these programs—Community Sex Offender Groupwork Program; Northumbria Sex Offender Groupwork Program; and Thames Valley Program—were evaluated together, since they are similar in the targets of intervention (Beech et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008). The other programs implemented were: Internet Sex Offender Treatment Programme (Middleton et al., 2009), Challenge Project (Craissati et al., 2009), Sex Offender Treatment and Evaluation Project (Marques et al., 2005), and Inform Plus Programme (Dervley et al., 2017). The remaining intervention program did not identify a specific treatment program (Serran et al., 2007).

The majority of the programs used both group and individual techniques (K = 6) and four intervention programs were administered only in groups (Dervley et al., 2017; Fisher et al., 2000; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007). In addition, a greater number of programs were applied in the community (K = 8) than in the prison setting (K = 2). The criteria for the duration of the whole program varied substantially across the intervention programs: four programs used the hour criteria (Beech et al., 2012; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008), four mentioned the months (Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Marques et al., 2005; Serran et al., 2007), and one pointed out the number of sessions (Middleton et al., 2009). The duration of the programs varied from 80 to 290 hrs. The programs that considered the months varied between 4 to 24 months. Only one program mentioned the number of sessions (35 sessions).

Almost all the intervention treatments included the cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with relapse prevention (RP) as their theoretical rationale (K = 7) (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2005). One program used CBT with RP and elements of the good lives model (GLM) (Middleton et al., 2009) and another used a combination of three models—model of change, model of problematic internet use, and GLM (Serran et al., 2007). Also, one study was CBT with GLM (Dervley et al., 2017).

Targets

Although related, some treatment targets vary substantially across the programs. So, we decided to cluster them into more generic categories to facilitate understanding of the topics covered in the intervention. An interpersonal module was created including topics such as relationships skills, assertiveness, problem-solving strategies, and self as a victim. Moreover, the fantasy and sexuality, offense-related fantasy, sex education, human sexuality, and intimacy deficits were grouped in an intimacy and sexual module. Topics such as relaxation, anger, and stress coping skills, impulsiveness control, and locus of control were grouped in the emotional self-management module. Lastly, an attitude module was formed with offense-supportive attitudes and cognitive distortions targets.

Nine intervention programs included a victim empathy module (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Colton et al., 2009; Dervley et al., 2017; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007) and eight programs had an interpersonal skills module (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2005; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007).

Seven intervention programs report attitudes as targets for intervention (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Colton et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2005; Middleton et al., 2009). Also, seven programs included a risk management and relapse prevention module (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Craissati et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007). Moreover, six intervention programs included an intimacy and sexual module (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Dervley et al., 2017; Elliott et al., 2019; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2005) and emotional self-management skills (Beech et al., 2012; Colton et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Marques et al., 2005; Middleton et al., 2009).

The remaining topics were understanding the cycle of offending (K = 4; Craissati et al., 2009; Dervley et al., 2017; Marques et al., 2005; Serran et al., 2007), taking responsibility for one’s behaviors (K = 3; Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Marques et al., 2005; Serran et al., 2007), motivation to change or motivation to get involved in the intervention (K = 2; Colton et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2000; Middleton et al., 2009), self-esteem (K=2; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007), and self-efficacy module (K = 1; Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003). Finally, there was a study that had an optional module for substance abuse problems (Marques et al., 2005) and another for addiction and collecting behaviors related to internet-specific factors (Dervley et al., 2017).

Intervention Outcomes

Quantitative Studies

Studies suggest that significant treatment gains were observed at posttreatment on psychological measures. For instance, Beech and Ford (2006) observed clinically significant changes in pro-offending attitudes and socio-affective functioning depending on the participants’ risk. Specifically, 25% of high deviance men achieved a treated profile compared to 48% low deviance men. The same was observed in Mandeville–Norden and colleagues’ study with 7–33% of the sample reaching clinically significant changes on pro-offending attitudes and socio-affective functioning and Middleton and colleagues’ study with 53% of the sample reaching a treated profile (Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009). However, in one study only the victim empathy dimension reached significant improvements (Elliott et al., 2019).

Using just two measures for the effectiveness of the intervention, Biddey and Beech (2003) found significant gains in changing cognitive distortions that rationalize sex offending and the effects of sexual assault on their victims on the approach pathway group. In addition, no significant changes were found in the avoidant pathway group. However, this group presented normative values in the pre-test.

Another study, which used the relapse prevention questionnaire to measure the effects of the intervention, described significant improvements in identifying risk situations and coping strategies (Fisher et al., 2000). Using other measures, Serran and colleagues (2007) identified an increase in the use of task-focused and social diversion strategies. Nevertheless, the individuals who completed the treatment program did not significantly alter the use of ineffective strategies to deal with stressful situations. For a full description of all outcomes measured in the included studies, see Table 2.

Additionally, only one study included a follow-up, observing significant treatment gains over a 9-month period (Fisher et al., 2000). However, among the studies evaluating the effectiveness of programs through pre-post measures, three showed acceptable quality (Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Elliott et al., 2019), and four did not show an acceptable quality and low risk of bias (Fisher et al., 2000; Mandeville-Norden et al., 2008; Middleton et al., 2009; Serran et al., 2007).

Five studies analyzed recidivism rates to evaluate the effects of psychological programs. Recidivism was defined as any new reconviction for a new sex offense after release (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Craissati et al., 2009; Elliott et al., 2019; Marques et al., 2005) and one study also reported the breach/recall to custody rates (Craissati et al., 2009). Three studies compared the recidivism rates of individuals defined as treated with those defined as untreated (Beech & Ford, 2006; Beech et al., 2012; Craissati et al., 2009). Treated profile was defined as no offense-specific problems and absence of socio-affective problems at the posttreatment stage. One study evaluated the effect of the program on two different samples without a control group (Elliott et al., 2019) and another one compared the recidivism rates of a treatment group with two control groups without any treatment (Marques et al., 2005). The follow-up period ranged from 2 to 14 years.

The rate of sexual recidivism of the individuals who reached the treated profile ranged between 0% to 9%, while the non-treated profile groups ranged between 14% and 16%. Elliott and his colleagues (2019) also showed that the sexual recidivism rate ranged between 10.1% and 26.4% within the two groups of treatment in analysis. When using a control group, Marques and colleagues (2005) did not find statistically significant differences between the treatment group and the control groups. Of the five studies, just one did not show an acceptable quality and low risk of bias (Beech et al., 2012). Excluding this study from the analysis, the rate of sexual recidivism of the individuals who reached the treated profile ranged between 0% and 7%, while the rate of sexual recidivism of the non-treated profile remained the same.

Qualitative Studies

In the first qualitative study included Colton and colleagues (2009), explored the participants’ views about the treatment program and the degree of relevance of each module in intervention. About half of the participants considered the victim empathy as the most helpful target in treatment (n = 20; 57.1%), following by the cycle of offending (n = 16; 45.7%), and the relapse prevention module (n = 14; 40.1%). Moreover, increased awareness of behavior and learning to accept responsibility were also two outstanding elements (25.7% and 14.3%, respectively). Lastly, through the interviews carried out, the participants also mentioned the motivation component as the key to therapeutic success as well as the importance of follow-up for addressing issues that may just come up in day-to-day life.

In line with that, Dervley and colleagues (2017) also found that understanding the cycle of offending was empowering for the participants. Their results also pointed out the importance of the motivation component as well as the relationships skills gains. The participants reported that the open and trusted environment in the group helped them to generalize these skills to their relationships. In addition, it showed that the program helped the individuals to eliminate a negative coping mechanism to deal with negative emotions.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to analyze the effects of psychological intervention with individuals who sexually offended against children, detailing the treatment procedures within the last two decades. This review revealed a few key findings related to the overall state of intervention programs of male adults convicted for child sexual abuse. First, CBT with RP approach was the widest modality studied in child sexual offending treatment. Besides that, other studies started to follow the tendency of the literature to also focus on a strength-based approach, introducing elements of the good lives model as a theoretical rationale for intervention (Ward & Gannon, 2006; Willis & Ward, 2011). Although recent literature has argued that intervention should consider distorted schemas and not just the distorted cognitions (e.g., Beech et al., 2013; Ó Ciardha & Gannon, 2011). At the same time, researchers argue that these patients would benefit from Young’s schema-focused model (Young et al., 2003), as it would allow to gain greater knowledge about the developmental and cognitive processes involved in sexual offending (Carvalho & Nobre, 2014; Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015). Despite that, none of the treatment programs reviewed had a schema component, focusing solely on surface-level cognitions.

Second, a variety of intervention targets were found, some of which considered by the literature as criminogenic needs of offenders (i.e., risk factors that are empirically linked to recidivism), and that, according to the RNR model, should be the target of intervention for reducing sexual reoffending (Bonta & Andrews, 2007; Hanson et al., 2009; Yates, 2013). Examples of these topics are interpersonal skills, attitudes, emotional self-management, and sexual or intimacy components. Although less frequent there were some non-criminogenic factors (Yates, 2013) included in interventions programs such as victim empathy, taking responsibility for their crimes, self-esteem, and self-efficacy factors. Some authors did not consider these factors adequate targets for intervention to reduce sexual risk (Bonta & Andrews, 2007), whereas others argued that they cannot be completely ignored since it is important to create conditions for change (Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson & Yates, 2013). The qualitative studies included in this review showed that participants considered non-criminogenic factors as relevant elements for change (Colton et al., 2009; Dervley et al., 2017). Therefore, it may be important to consider the non-criminogenic factors for understanding which and how they influence the process of change and whether they should be incorporated as intervention elements. Although they may not contribute to reducing the risk of reoffending, they can enhance the individual’s well-being, which can influence successful client engagement (Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson & Yates, 2013). This can be important since there is a gradual shift from an intervention focused solely on reducing the risk of recidivism to increasing the well-being of the participants as well (e.g., Wormith et al., 2007).

In line with that, another component of treatment that is pointed out as a crucial issue in child sexual offending treatment is motivation to change one’s sexual offending behavior (Lösel & Schmucker, 2017; Tierney & McCabe, 2002). Yet, just two intervention programs included in the review addressed this component (Colton et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2000; Middleton et al., 2009). Also, there is a specific feature in child sexual offending treatment approaches that fail to motivate clients such as taking full responsibility for all past offenses (Marshall & Marshall, 2017L. E. Marshall & Marshall, 2017), which was present in three programs (Beech & Ford, 2006; Biddey & Beech, 2003; Marques et al., 2005; Serran et al., 2007).

However, problems with study design, study quality, and intervention procedures endanger the accumulation of evidence-based practices for the effective treatment of individuals who sexually offended against children. Samples lacking comparison groups limit the capacity to generalize the results to all child sexual crimes. The only two studies that had a comparison group evaluated the treatment effectiveness in different ways and showed different results. Marques and colleagues (2005) revealed that treatment was not effective in reducing sex offending recidivism and Serran and colleagues (2007) showed significant improvements in cognitive and behavioral skills. The problem of design and quality of studies was mentioned in previous reviews about child sexual offending as one of the major problems in this field (e.g., Walton & Chou, 2015; Gronnerod et al., 2015). However, research continues to not use robust enough designs to attest to the effectiveness of interventions (e.g., Gronnerod et al., 2015; Walton & Chou, 2015).

Furthermore, how the programs are created and described in the evaluation studies may benefit by taking into account some aspects, namely, most studies specified neither the participants’ level of risk nor the level of risk that the treatment addresses. In fact, although the literature has shown that the treatment should take into account the principles of the RNR model to achieve better results (Hanson et al., 2009; Olver, 2016), it is unclear if the intervention procedures addressed the risk principle. Another limitation regarding the intervention procedures was the wide variation in the time criteria and the length of interventions. This raises questions about the “dose-effect” of treatment to produce positive changes. In addition, it is not possible to compare results across studies with such a different treatment dose and time criteria (Olver, 2016).

Some intervention programs are directed for individuals who sexually offended but they do not consider the existence of different criminological needs (Sigre-Leirós et al., 2015; Walton & Chou, 2015). Therefore, it is unclear how the interventions discussed in this study were modified or adapted to address specifically the treatment needs and characteristics of the distinct groups of individuals who sexually offended against children. The same happened with the subtypes of individuals convicted for child sexual crimes: four studies included individuals convicted for child pornography in the sample and just one (Middleton et al., 2009) is exclusively aimed at individuals convicted of these crimes. Moreover, literature shows that a considerable number of individuals who sexually offended against children have a record of sexual abuse during their childhood and/or adolescence (Babchishin et al., 2011; Levenson et al., 2016). Some studies revealed that having a history of trauma can restrain the effective participation of individuals (Ricci & Clayton, 2008). None of the programs appeared to address this factor, so perhaps it could be a variable consider in the future.

The failure to disclose important information about the treatment implementation requires attention. Several studies have highlighted the central role that therapist-related variables play in explaining outcomes in psychotherapy (Baldwin & Imel, 2013; Johns et al., 2019). In fact, a recent meta-analysis has reported the influence of the therapists' training on the effectiveness of the intervention (Gannon et al., 2019). Thus, it would be important for treatment programs to begin to approach therapists’ background and training.

Lastly, how programs are evaluated might also raise some questions. Our results showed that the most common evaluation method was the measurement of changes in pre-post treatment variables, followed by the combined use of pre-post treatment change and recidivism, thus not following the tendency of literature in focusing on recidivism as a primary concern when assessing psychological interventions (e.g., Hanson et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2016; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005; Mpofu et al., 2018). The use of the recidivism rates and pre-post treatment changes in combination could be important since it allows to know if treatment reduces recidivism, promote changes in criminological factors, and what changes lead individuals to desist from offending (Marshall et al., 2017; Nunes et al., 2011). However, the CODC guidelines only focus on studies that address recidivism (Beech et al., 2007a; Beech et al., 2007b). Therefore, it may be important to reformulate CODC guidelines to include criteria for eliminating threats to validity in studies that measure the effectiveness of intervention in the short term.

Conclusion

Several findings emerge from this review. (Tables 3 and 4) Criminogenic and non-criminogenic factors emerge as important targets for psychological intervention with individuals who sexually offended against children. Studies must evaluate the impact of non-criminogenic factors on therapy engagement and treatment outcomes. Additionally, the way studies evaluated the treatment programs might be reconsidered. The use of the recidivism rates and pre-post treatment changes in combination could be important since it allows us to know if treatment reduces recidivism, promote changes in criminogenic factors, and what changes lead individuals to desist from offending. Besides that, it may be important to reformulate CODC guidelines to include criteria for eliminating threats to validity in studies that measure pre-post treatment change. Moreover, social scientists must be more thorough in describing treatment procedures and therapists’ backgrounds. Future studies would benefit from a better explanation of how treatment modalities were modified to account for individuals who sexually offended against children (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Critical findings.

| Critical findings |

|---|

| • First, we found that the cognitive-behavioral model with a relapse prevention approach was the most frequent modality studied in child sexual offending treatment. |

| • Second, we found that different criminogenic and non-criminogenic factors emerge as targets for psychological intervention with individuals who sexually offended against children. |

| • Third, study design, study quality, and intervention procedures compromise the accumulation of evidence in treatment effectiveness. |

Table 4.

Summary of Implications for practice, policy, and research.

| Implications for practice, policy, and research |

|---|

| 1. Treatment programs should be undertaken in the context of high-quality research following methodological principles that decreased bias. Despite this, we encourage reformulating CODC guidelines to include criteria for eliminating validity’ threats in studies that measure the effectiveness of intervention in the short term. |

| 2. Researchers should focus on the non-criminogenic factors for understanding which and how they influence the process of change and whether they should be incorporated as intervention elements. |

| 3. Researchers should use both recidivism rates and pre-post treatment changes because it helps to know if treatment reduces recidivism, promotes changes in criminological factors, and what kind of changes lead individuals to desist from offending. |

| 4. Practitioners should focus on the risk level of the participants when creating the intervention programs since it allows to identify the appropriate dosage of treatment. |

| 5. Practitioners should consider both the presence of traumatic events (i.e., sexual abuse) and the motivational state that is known to have an early influence on the therapeutic process when creating the psychological intervention programs. |

| 6. Practitioners should consider intervention on a deeper level (i.e., schema-focused). It enables the individual to work toward a more functional life, gaining greater knowledge about the developmental and cognitive processes involved in sexual offending. |

| 7. Research on the effectiveness of intervention programs should begin to approach therapists’ background and training since several studies have highlighted the central role that therapist-related variables play in the outcomes of psychotherapy. |

Limitations

For the present study, we included only studies with men who committed sex crimes against children. Thus, our results cannot be generalized to women who were convicted of child sexual abuse.

Author Biographies

Marta Sousa is Ph.D. student at Psychology Research Center (CIPSI), School of Psychology, University of Minho (Braga, Portugal). She is a psychologist with a master’s degree in Applied Psychology. The main focus of her work is on the characterization and psychological intervention of individuals who sexually offended against children

Joana Andrade is Researcher at the Psychology Research Centre at the University of Minho. She is a Portuguese psychologist with a Master’s Degree in Applied Psychologist. Her research interests are, among others, in criminality, offending behavior, and offenders’ treatment and rehabilitation

Andreia de Castro Rodrigues is Assistant Professor at ISPA—University Institute and a Researcher at William James Center for Research (Lisbon, Portugal). She developed her post-doc research and her Ph.D. in Psychology of Justice, respectively, in the area of users’ perceptions and effectiveness of penal sanctions and sentencing

Rui Abrunhosa Gonçalves is Associate Professor with tenure at the School of Psychology in the University of Minho (Braga, Portugal), where in 1997, he took his Ph.D. in Forensic and Legal Psychology. He also works as a forensic psychologist expert at the Counselling Unit of Forensic Psychology of the University of Minho.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was conducted at the Psychology Research Center (PSI/01662), School of Psychology, University of Minho. Marta Sousa was funded by a Doctoral research grant from Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, grant number 2020.06634.BD.

ORCID iD

Marta Sousa https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3258-9932

References

- Babchishin K. M., Hanson R. K., Hermann C. A. (2011). The characteristics of online sex offenders: a meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 23(1), 92–123. 10.1177/1079063210370708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S. A., Imel Z. E. (2013). Therapist Effects: Findings and Methods. In Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Beech A., Bourgon G., Hanson R., Hanson R. K., Harris A. J. R., Langton C., Marques J., Miner M., Murphy W., Quinsey V., Seto M., Thornton D., Yates P. M. (2007. a). Sexual offender treatment outcome research: CODC guidelines for evaluation Part 1: Introduction and overview. May 2014 (pp. 1–21). Public Safety Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Beech A., Bourgon G., Hanson R. K., Harris A. J. R., Langton C., Marques J., Miner M., Murphy W., Quinsey V., Seto M., Thornton D., Yates P. M. (2007. b). The collaborative outcome data committee’s guidelines for the evaluation of sexual offender treatment outcome research Part 2: CODC guidelines. Public Safety Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Beech A. R., Bartels R. M., Dixon L. (2013). Assessment and treatment of distorted schemas in sexual offenders. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 14(1), 54–66. 10.1177/1524838012463970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech A., Ford H. (2006). The relationship between risk, deviance, treatment outcome and sexual reconviction in a sample of child sexual abusers completing residential treatment for their offending. Psychology, Crime and Law, 12(6), 685–701. 10.1080/10683160600558493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beech A. R., Mandeville-Norden R., Goodwill A. (2012). Comparing recidivism rates of treatment responders/nonresponders in a sample of 413 child molesters who had completed community-based sex offender treatment in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 56(1), 29–49. 10.1177/0306624X10387811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddey J. A., Beech A. R. (2003). Implications for treatment of sexual offenders of the ward and hudson model of relapse. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 15(2), 121–134. 10.1023/A:1022342032083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonta J., Andrews D. (2007). Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation, 6(1), 1–22. 10.1002/jclp.20317 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffard J. A., Askew L. Q. N. (2019). Time-series analyses of the impact of sex offender registration and notification law implementation and subsequent modifications on rates of sexual offenses. Crime and Delinquency, 65(11), 1483–1512. 10.1177/0011128717722010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. (2005). Development/history of sex offender treatment programmes. In Brown S. (Ed.), Treating Sex Offenders: An introduction to sex offender treatment programmes (pp. 17–40). Willan. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho J., Nobre P. J. (2014). Early maladaptive schemas in convicted sexual offenders: Preliminary findings. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 37(2), 210–2166. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church W. T., Sun F., Li X. (2011). Attitudes toward the treatment of sex offenders: A SEM Analysis. Journal of Forensic Social Work, 1(1), 82–95. 10.1080/1936928x.2011.541213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colton M., Roberts S., Vanstone M. (2009). Child sexual abusers’ views on treatment: A study of convicted and imprisoned adult male offenders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 18(3), 320–338. 10.1080/10538710902918170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craissati J., South R., Bierer K. (2009). Exploring the effectiveness of community sex offender treatment in relation to risk and re-offending. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 20(6), 769–784. 10.1080/14789940903174105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dervley R., Perkins D., Whitehead H., Bailey A., Gillespie S., Squire T. (2017). Themes in participant feedback on a risk reduction programme for child sexual exploitation material offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(1), 46–61. 10.1080/13552600.2016.1269958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott I. A., Mandeville-Norden R., Rakestrow-Dickens J., Beech A. R. (2019). Reoffending rates in a U.K. community sample of individuals with convictions for indecent images of children. Law and Human Behavior, 43(4), 369–382. 10.1037/lhb0000328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D., Beech A., Browne K. (2000). The effectiveness of relapse prevention training in a group of incarcerated child molesters. Psychology, Crime and Law, 6(3), 181–195. 10.1080/10683160008409803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flinton C. A., Adams J., Adams J., Bennett C., D’Orazio D., Miccio-Fonseca L., Fox D. (2010). Guidelines and best practices: Adult male sexual offender treatment. CCOSO. http://ccoso.org/sites/default/files/adultguidelines.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gannon T. A., Olver M. E., Mallion J. S., James M. (2019). Does specialized psychological treatment for offending reduce recidivism? A meta-analysis examining staff and program variables as predictors of treatment effectiveness. Clinical Psychology Review, 73(101752). 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronnerod C., Gronnerod J. S., Grondahl P. (2015). Psychological treatment of sexual offenders against children: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcome studies. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 16(3), 280–290. 10.1177/1524838014526043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi L. M. (2017). Sexual offenders, violent offenders, and community reentry: Challenges and treatment considerations. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 59–67. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hailes H. P., Yu R., Danese A., Fazel S. (2019). Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: An umbrella review. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 830–839. 10.1016/S2215-0366(19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. K., Bourgon G., Helmus L., Hodgson S. (2009). The principles of effective correctional treatment also apply to sexual offenders: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(9), 865–891. 10.1177/0093854809338545 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. K., Gordon A., Harris A. J., Marques J. K., Murphy W., Quinsey V. L., Seto M. C. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 14(2), 169–177. 10.1177/107906320201400207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. K., Yates P. M. (2013). Psychological treatment of sex offenders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15(3), 348–8. 10.1007/s11920-012-0348-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C. A., Hogue T. E., Bartels R. M. (2017). Attitudes towards sexual offenders: What do we know, and why are they important? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 201-213. 10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q., Pluye P., Fàbregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M.-P., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., O’Cathain A., Rousseau M.-C. (2018). Vedel I. Mixed methods appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Ho D., Ross C. (2012). Cognitive bahaviour therapy for sex offenders. Too Good to Be True? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22(1), 1–13. 10.1002/cbm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings J. L., Deming A. (2013). Effectively utilizing the “behavioral” in cognitive-behavioral group therapy of sex offenders. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 87(2), 7–13. 10.1037/h0100968 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johns R. G., Barkham M., Kellett S., Saxon D. (2019). A systematic review of therapist effects: A critical narrative update and refinement to Baldwin and Imel’s (2013) review. Clinical Psychology Review, 67, 78-93. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal C. C., Beaulieu-Plante J., de Chantérac A. (2014). The neuropsychology of sex offenders: A meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 149–177. 10.1177/1079063213482842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Benekos P. J., Merlo A. V. (2016). Sex offender recidivism revisited: review of recent meta-analyses on the effects of sex offender treatment. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 17(1), 105–11717. 10.1177/1524838014566719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Långström N., Enebrink P., Laurén E. M., Lindblom J., Werkö S., Hanson R. K. (2013). Preventing sexual abusers of children from reoffending: Systematic review of medical and psychological interventions. BMJ, 347(7924), f4630–11. 10.1136/bmj.f4630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws D. R. (2003). The rise and fall of relapse prevention. Australian Psychologist, 38(1), 22–30. 10.1080/00050060310001706987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laws D. R., Marshall W. L. (2003). A brief history of behavioral and cognitive behavioral approaches to sexual offenders: Part 2. The Modern Era. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 15(2), 75–92. 10.1023/A:1022325231175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson J. S., Willis G. M., Prescott D. S. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences in the lives of male sex offenders: Implications for Trauma-Informed Care. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 28(4), 340–359. 10.1177/1079063214535819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lösel F., Schmucker M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(1), 117–146. 10.1007/s11292-004-6466-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lösel F., Schmucker M. (2017). Treatment of sex offenders: Concepts and empirical evaluations. The Oxford Handbook of Sex Offences and Sex Offenders, 392–414. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190213633.013.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandeville-Norden R., Beech A., Hayes E. (2008). Examining the effectiveness of a UK community-based sexual offender treatment programme for child abusers. Psychology, Crime and Law, 14(6), 493–512. 10.1080/10683160801948907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques J. K., Wiederanders M., Day D. M., Nelson C., Van Ommeren A. (2005). Effects of a relapse prevention program on sexual recidivism: Final results from California’s Sex Offender Treatment and Evaluation Project (SOTEP). Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment, 17(1), 79–107. 10.1007/s11194-005-1212-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. L., Hollin C. (2015). Historical developments in sex offender treatment. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 21(2), 125–135. 10.1080/13552600.2014.980339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall L. E., Marshall W. L. (2017) Motivating sex offenders to enter and effectively engage in treatment. In Wilcox D., Donathy M., Gray R., Brain C. (Eds.), Working with Sex Offenders: A Guide for Practitioners (pp. 98–112). Routledge. 10.4324/9781315673462-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W. L., Marshall L. E., Olver M. E. (2017). An evaluation of strength-based approaches to the treatment of sex offenders: A review. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 7(3), 221–228. 10.1108/JCP-04-2017-0021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire R. J., Carlisle J. M., Young B. G. (1964). Sexual deviations as conditioned behaviour: A hypothesis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 2(2–4), 185–190. 10.1016/0005-7967(64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton D., Mandeville-Norden R., Hayes E. (2009). Does treatment work with internet sex offenders? Emerging findings from the internet sex offender treatment programme (i-SOTP). Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15(1), 5–19. 10.1080/13552600802673444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu E., Athanasou J. A., Rafe C., Belshaw S. H. (2018). Cognitive-behavioral therapy efficacy for reducing recidivism rates of moderate- and high-risk sexual offenders: A scoping systematic literature review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(1), 170–186. 10.1177/0306624X16644501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes K. L., Babchishin K. M., Cortoni F. (2011). Measuring treatment change in sex offenders: Clinical and statistical significance. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 38(2), 157–173. 10.1177/0093854810391054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ó Ciardha C., Gannon T. A. (2011). The cognitive distortions of child molesters are in need of treatment. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 17(2), 130–141. 10.1080/13552600.2011.580573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olver M. E. (2016). The risk-need-responsivity model: Applications to sex offender treatment. In Boer W. L. M. D. P., Beech A. R., Ward T., Craig L. A., Rettenberger M., Marshall L. E. (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook on the Theories, Assessment and Treatment of Sexual Offending (pp. 1313–1329). Wiley Blackwell. 10.1002/9781118574003.wattso061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci R. J., Clayton C. A. (2008). Trauma resolution treatment as an adjunct to standard treatment for child molesters. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2(1), 41–50. 10.1891/1933-3196.2.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M., Grant H. (2013). Treatment for adult sex offenders: May we reject the null hypothesis? In Harrison K., Rainey B. (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Legal and Ethical Aspects of Sex Offender Treatment and Management (pp. 217–235). John Wiley & Sons. 10.1002/9781118314876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M., Harris G. (2003). The size and sign of treatment effects in sex offender therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 989(1), 428–435. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07323.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker M., Lösel F. (2015). The effects of sexual offender treatment on recidivism: An international meta-analysis of sound quality evaluations. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11(4), 597–630. 10.1007/s11292-015-9241-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serran G. A., Firestone P., Marshall W. L., Moulden H. (2007). Changes in coping following treatment for child molesters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 22(9), 1199–1210. 10.1177/0886260507303733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigre-Leirós V., Carvalho J., Nobre P. (2015). Cognitive schemas and sexual offending: Differences between rapists, pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters, and nonsexual offenders. Child Abuse and Neglect, 40, 81-92. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldino V., Carbonell-Vayá E. J. (2017). Efecto del tratamiento sobre la reincidencia de delincuentes sexuales: Un meta-análisis. Anales de Psicologia, 33(3), 578–588. 10.6018/analesps.33.2.267961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney D. W., McCabe M. P. (2002). Motivation for behavior change among sex offenders. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(1), 113–129. 10.1016/s0272-7358(01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler N., Gannon T. A., Olver M. E. (2021). Does Treatment for Sexual Offending Work? Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(8), 1–8. 10.1007/s11920-021-01259-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton J. S., Chou S. (2015). The effectiveness of psychological treatment for reducing recidivism in child molesters: A systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 16(4), 401–417. 10.1177/1524838014537905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Gannon T. A. (2006). Rehabilitation, etiology, and self-regulation: The comprehensive good lives model of treatment for sexual offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(1), 77–94. 10.1016/j.avb.2005.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T., Stewart C. A. (2003). The treatment of sex offenders: Risk management and good lives. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(4), 353–360. 10.1037/0735-7028.34.4.353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis G. M., Malinen S., Johnston L. (2013). Demographic differences in public attitudes towards sex offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 20(2), 230-247. 10.1080/13218719.2012.658206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willis G. M., Ward T. (2011). Striving for a good life: The good lives model applied to released child molesters. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 17(3), 290–303. 10.1080/13552600.2010.505349 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wormith J. S., Althouse R., Simpson M., Reitzel L. R., Fagan T. J., Morgan R. D. (2007). The rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders: The current landscape and some future directions for correctional psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(7), 879–892. 10.1177/0093854807301552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele S. K. (2016). Understanding and preventing the sexual exploitation of youth. The curated reference collection in neuroscience and biobehavioral Psychology. Elsevier. 10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.05192-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yates P. M. (2013). Treatment of sexual offenders: Research, best practices, and emerging models. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 8(3–4), 89–95. 10.1037/h0100989 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. E., Klosko J. S., Weishaar M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]