Abstract

Objective

Health communication is a novel field in the Arab world. This study aimed to describe and characterise health communication research activity in the region.

Methods and analysis

The PubMed database was used to search for publications related to health communication from Arab states. Publications were classified according to country of origin, without limiting for date. Research activity and output were examined with respect to population and the gross domestic product (GDP) of each Arab state.

Results

A total of 66 contributions related to health communication came from the Arab countries, with the first paper published from Lebanon in 2004. Health communication-related publications constituted 0.03% of the total biomedical research contributions published by the Arab world since 2004 and 1% of the world’s health communication literature. Number of health communication contributions ranged between 0 and 12, with Lebanon producing the most output. Qatar ranked first with respect to contributions per population, whereas Lebanon ranked first with respect to contributions per GDP. Algeria, Comoros, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen had nil health communication publications.

Conclusion

Recognising the barriers facing the health communication field and addressing them carefully are vital in the plan to better the Arab world’s output and contribution in the field.

Keywords: communication, health policy, health services research, global health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

What is already known about this subject?

Health communication, as an independent field, is new to the Arab world.

What does this study add?

Health communication-related publications constituted 0.03% of the total biomedical research contributions published by the Arab world since 2004, and 1% of the world’s health communication literature. Publication revolved around three main themes: the role of media in health promotion, health communication in conflict and the role of health communication in the fight against health risk factors. Lebanon was the Arab state that is most indulged in the health communication field.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

Political and economic perturbations in the Arab world contribute to the decline in research activity in the health communication field. Budgetary efforts should be dedicated to fund biomedical research, in general, and health communication research, in specific. This work calls for academic programmes that explore health communication and emphasise the importance and influence of the field in the health sector.

Introduction

Health communication is a broad term that is mainly defined as the study or use of communication techniques to improve the health sector. It includes strategies used to build awareness and spread information about health among people, in general, and patients, in specific.1 The importance of this field is that it allows people to acquire a better understanding of how to maintain a healthy lifestyle and to learn more about the major health risks that threaten their communities. In addition, it promotes effective means of communication among health workers of various disciplines, as well as between health workers and patients.2

The term ‘health communication’ formally originated in the mid-1970s when members of an International Communication Association interest group adopted the label ‘health communication.’3 Nonetheless, the inter-relation that exists between ‘health’ and ‘communication’ developed long before; its fundamentals emerged and were practised since the birth of humanity.4 Across generations, people communicated on healthy lifestyles, practices and diets. Ancient people, for example, taught each other the different ways to treat wounds, what to eat and how to act when danger approaches.5 Interest and progress in the field soared high in the early 21st century as a result of growing interest in public health policy.3 Major health risks like smoking, substance abuse, obesity and infectious diseases gave the field a strong push forward to garner more interest and increased funding for research and organisational structuring. The recent rise in the influence of social media facilitated the promotion of health awareness campaigns led by governmental and non-governmental agencies. This increased the impact of the field and highlighted the importance of exploring, in depth, the science and art that lie at the basis of health communication.

In the past two decades, the health scene in the Arab world has become increasingly intricate. Although countries of the Arab world are pretty diverse, most of the 22 countries that comprise the Arab League and share the common language of Arabic are embroiled in conflict, instability, poverty and/or corruption.6 This takes its toll on the health sector, whereby the need to address public health problems like war injuries, refugee crises, pollution, and communicable and non-communicable diseases rises.7

As an independent field in the Arab world, health communication is relatively new. In 2019, the first undergraduate programme in health communication was launched in Lebanon, becoming the first of its kind in the Arab world.8 Yet, the growth of the field in this region requires substantial investment to develop and tailor health communication strategies to public health needs. As such, research becomes imperative to the process. In this work, we aimed to explore the bibliometric patterns of health communication research in the Arab world. Subsequently, this will allow us to evaluate the current status of the field in the region and to identify inadequacies in the present case.

Materials and methods

On 7 October 2019, we searched the PubMed database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information to find publications related to health communication in the Arab world. Following the schema of Fares et al,9 relevant contributions were identified by using the term ‘health communication’ as a constant in the search field, followed by a separator Boolean operator (AND), followed by the name of the Arab country (eg, ‘Morocco’). We searched for all publications since database inception, without specifying a time frame. Then, we identified the publications that had authors contributing from 1 of the 22 states of the Arab world.

We calculated the number of contributions per country’s population to eliminate bias due to varying population sizes. We did so by dividing the number of contributions by the average population estimate (per one million individuals) of each country since the year of the first health communication publication in each country and the year of the first Arab publication in health communication, respectively.

We also calculated the number of contributions per gross domestic product (GDP) in order to eliminate any bias due to the vast differences in the GDPs of Arab countries. We did so by dividing the number of contributions in each country by its average GDP in billion US$ since the year of the first publication in health communication in the specific country and the year of the first Arab publication in health communication, respectively.

Information on Arab world population and GDP was retrieved from the websites of the World Population Review (http://worldpopulationreview.com/) and The World Bank Open Data (https://data.worldbank.org/), respectively.

Patient and public involvement statement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or to interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Results

In total, 66 contributions related to health communication originated from the Arab world, with the first paper published in 2004. Health communication-related publications constituted 0.03% of the total biomedical research papers published by the Arab world and 1% of the world’s health communication literature (table 1).

Table 1.

Ratio of health communication contributions to total biomedical contributions in the Arab world since the year of first publication by state and the year of first Arab publication (2004), as of 7 October 2019

| Country | Year of first publication in the country | Health and communication contributions (n) | Biomedical contributions since the year of first health communication publication per state (total n) | Per cent of health communication contributions since the year of first publication | Contributions since 2004 (total n) | Per cent of health communication contributions since 2004 |

| Algeria | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bahrain | 2017 | 3 | 644 | 0.47 | 1821 | 0.165 |

| Comoros | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Djibouti | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 2017 | 6 | 23 651 | 0.025 | 60 212 | 0.010 |

| Iraq | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jordan | 2013 | 6 | 3459 | 0.173 | 4843 | 0.124 |

| Kuwait | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lebanon | 2004 | 12 | 11 144 | 0.108 | 11 144 | 0.108 |

| Libya | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mauritania | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Morocco | 2013 | 5 | 7011 | 0.07 | 10 750 | 0.047 |

| Oman | 2014 | 4 | 4228 | 0.09 | 7333 | 0.055 |

| Palestine | 2017 | 2 | 837 | 0.24 | 2088 | 0.096 |

| Qatar | 2014 | 10 | 7583 | 0.13 | 9181 | 0.109 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2015 | 9 | 36 788 | 0.02 | 56 285 | 0.016 |

| Somalia | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sudan | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Syria | 2019 | 1 | 302 | 0.33 | 3005 | 0.033 |

| Tunisia | 2019 | 1 | 1630 | 0.06 | 18 028 | 0.006 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2011 | 7 | 7245 | 0.096 | 8754 | 0.080 |

| Yemen | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 66 | 193 444 | 0.034 |

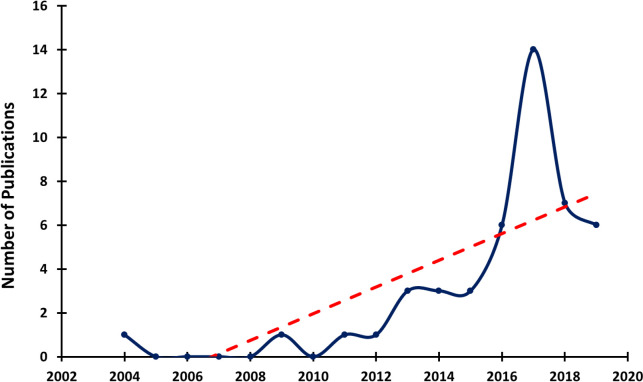

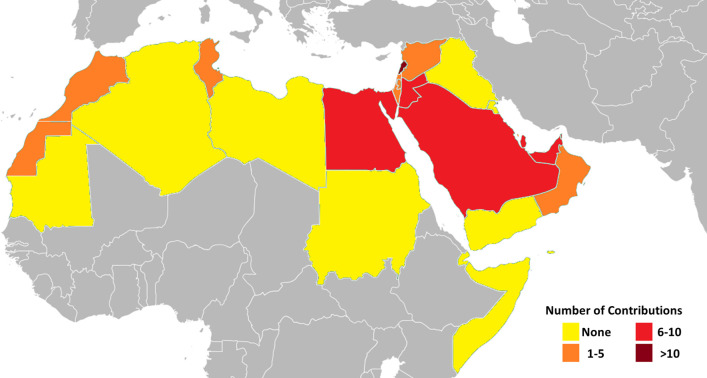

Since 2004, the health communication research output in the Arab world has been on the rise (figure 1). Research activity peaked during the year 2017, during which a collection of 31 research items (~47% of the total Arab contributions in health communication) were published. With respect to output per Arab country, the number of health communication publications ranged from 0 (Algeria, Comoros, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen) to 12 (Lebanon) (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of health communication research publications in the Arab world across the years. Note the increasing trend of health communication research output (red line).

Figure 2.

Distribution of health communication research contributions in the Arab world.

Analysing the research activity of each state separately and the Arab world as a whole in terms of contributions per population estimate, we found that Qatar ranked first with a ratio of 4.3 contributions per million persons, ahead of Bahrain and Lebanon with ~2 contributions per million persons each (table 2). Similarly, in terms of contributions per national GDP, Lebanon ranked first with a ratio of 0.308 contributions per billion US$, ahead of Jordan and Palestine, which scored ratios of 0.214 and 0.209 contributions per billion US$, respectively (table 3). Algeria, Comoros, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen all ranked last with nil health communication publications.

Table 2.

Ratio of health communication contributions to population estimate (per million individuals) in the Arab world since the year of first publication by state and the year of first Arab publication (2004) as of 7 October 2019

| Country | Year of first publication of the country | Health and communication contributions (n) | Average population since the year of first publication (×106) | Ratio of health communication papers per million individuals since year of first publication | Average population since 2004 (×106) | Ratio of health communication papers per million individuals since 2004 |

| Algeria | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bahrain | 2017 | 3 | 1.570 | 1.911 | 1.340 | 2.239 |

| Comoros | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Djibouti | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 2017 | 6 | 98.418 | 0.061 | 91.490 | 0.066 |

| Iraq | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Jordan | 2013 | 6 | 9.735 | 0.616 | 8.814 | 0.681 |

| Kuwait | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lebanon | 2004 | 12 | 6.200 | 1.935 | 6.200 | 1.935 |

| Libya | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mauritania | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Morocco | 2013 | 5 | 35.570 | 0.141 | 34.390 | 0.145 |

| Oman | 2014 | 4 | 4.640 | 0.862 | 4.110 | 0.973 |

| Palestine | 2017 | 2 | 4.840 | 0.413 | 4.480 | 0.446 |

| Qatar | 2014 | 10 | 2.710 | 3.690 | 2.320 | 4.310 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2015 | 9 | 33.050 | 0.272 | 30.920 | 0.291 |

| Somalia | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sudan | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Syria | 2019 | 1 | 17.070 | 0.059 | 18.040 | 0.055 |

| Tunisia | 2019 | 1 | 11.690 | 0.086 | 11.130 | 0.090 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2011 | 7 | 9.500 | 0.737 | 8.660 | 0.808 |

| Yemen | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Table 3.

Ratio of health communication contributions to GDP (billion US$) in the Arab world since the year of first publication by state and the year of first Arab publication (2004) as of 7 October 2019

| Country | Year of first publication of the country | Health and communication contributions (n) | Average GDP (in billion US$) since the year of the first publication | Ratio of health communication papers per average GDP (in billion US$) since year of first publication | Average GDP (in billion US$) since 2004 | Ratio of health communication papers per average GDP (in billion US$) since 2004 |

| Algeria | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Bahrain | 2017 | 3 | 36.59 | 0.0820 | 27.05 | 0.111 |

| Comoros | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Djibouti | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Egypt | 2017 | 6 | 243.13 | 0.025 | 215.90 | 0.028 |

| Iraq | – | – | 207.73 | 0.0337 | 150.81 | 0.046 |

| Jordan | 2013 | 6 | 38.34 | 0.156 | 27.92 | 0.214 |

| Kuwait | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lebanon | 2004 | 12 | 38.90 | 0.308 | 38.89 | 0.308 |

| Libya | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mauritania | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Morocco | 2013 | 5 | 108.27 | 0.0462 | 93.17 | 0.054 |

| Oman | 2014 | 4 | 15 926.33 | 0.0003 | 5340.54 | 0.001 |

| Palestine | 2017 | 2 | 14.56 | 0.1374 | 9.57 | 0.209 |

| Qatar | 2014 | 10 | 175.73 | 0.057 | 132.47 | 0.075 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2015 | 9 | 692.57 | 0.012 | 569.18 | 0.016 |

| Somalia | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sudan | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Syria | 2019 | 1 | 40.410* | 0.0247 | 31.92 | 0.031 |

| Tunisia | 2019 | 1 | 36.861* | 0.0271 | 41.24 | 0.024 |

| United Arab Emirates | 2011 | 7 | 378.80 | 0.0185 | 313.18 | 0.022 |

| Yemen | – | – | – | – | – | – |

*GDP for the year 2018 was used since the 2019 GDP was not available.

GDP, gross domestic product.

Discussion

Health communication is a novel field in the Arab world. The 22 Arab countries combined contributed only 1% of the world’s literature on health communication. Publication revolved around three main themes: the role of media in health promotion, health communication in conflict and the role of health communication in the fight against health risk factors. Lebanon was the Arab state that is most indulged in the health communication field.

Health communication needs and concerns differ from one Arab state to another. The research focus of high-income countries with rapid social and economic development, like Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, is different from that of low-income countries like Somalia, Sudan and Yemen, which suffer from lack of resources and political instability. Moreover, middle-income countries like Lebanon, Egypt and Jordan, which possess limited resources but well-developed health services, shared some of the concerns of high-income and low-income countries.

Many health communication papers were themed depending on the context and policy landscape of the Arab state of origin. In Lebanon, health communication studies mostly focused on three major health problems that the nationals in the country deal with: cancer, smoking and the refugee crisis. Promoting cancer awareness and establishing treatment guidelines were the focus of two health communication papers,10 11 especially after the rise in the number of cancer cases in the past decade.12–15 Another study explored the role of religion in dictating smoking behaviour in the country.16 Similarly, in Palestine, religion was also studied in terms of its influence on alcoholic habits.17 The use of media strategies to influence national habits and health policy was also highlighted in other studies.18–21 The refugee crisis, resulting from the repercussions of conflict and war in the region, was emphasised when exploring communal adaptability during times of uncertainty.22 In Jordan, health communication publications centred on an important national issue: family planning. One study explored a client-centred family planning service and the role it can play in attaining Jordan's goal of reducing the total fertility rate to its desired rate by 2030.23 In Saudi Arabia, studies mostly focused on the role of social media in promoting health awareness.24–28 Interestingly, Twitter was the social media platform mostly investigated.29 In the United Arab Emirates, one study analysed the content of Arabic and English newspapers in promoting a vaccination campaign against the human papillomavirus.30 Another study focused on childhood obesity perception among parents to promote the management and prevention of this health concern in the country.31 Physical inactivity and obesity were also highlighted in a study from Oman, whereby the perceptions of public health managers were explored in regard to this health inadequacy.32 In Morocco, one study explored courtesy stigma as a process experienced by health professionals providing HIV/AIDS care.33 Another study focused on ways to improve the outcomes of paediatric Hodgkin lymphomas.34 In Qatar, health communication research tackled the low literacy levels of the migrant workforce, and thus one study focused on developing easy-to-understand illustrations for medicine labels to ease comprehension and to promote medication safety.35 The Qatari emergency risk communication and response to the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in 2013 was also explored.36 Recommendations were drawn to develop more rigorous strategies that address proper health communication across social media platforms.36

Some collaborative efforts between researchers from different Arab states addressed common health concerns, like smoking and viral infections. With smoking rates being among the highest worldwide in the Arab world, one study focused on health warning labels that are waterpipe-specific; researchers from Lebanon, Syria and Tunisia contributed in the process.37 Scientific evidence about the waterpipe's harmful effects and the importance of tobacco control were emphasised in the labelling strategies.37 Furthermore, endemic infectious disease, like viral hepatitis C, necessitated contributions from several affected Arab states. Researchers from Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Oman, Qatar and Bahrain collaborated to study disease burden38 and epidemiological patterns39 and to develop strategies to counter the disease.40

Still, the research output of the Arab world in health communication is low. The poor status of biomedical research in the Arab world, in general, can be a major reason behind the low output in health communication.41–43 The lack of infrastructure and the continuous migration of researchers towards Western countries that offer better living and work opportunities exacerbate the problem.6 42 More importantly, political instability and military conflicts in many of the Arab states,44 like Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Palestine and Libya, are a major obstacle for the development of clinical research, in general, and health communication, in specific.

Arab states with nil publications in health communication were mostly low-income countries like Yemen, Djibouti, Mauritania and Comoros. These countries suffer from widespread poverty, low security, poor health services, and lack of education and proper nutrition. Studies show that poor governance, exploitation and technological dependency are tightly linked to poor scientific performance.42 45–47 As such, academic research is sidelined over fulfilling more basic needs. Surprisingly, Kuwait, which is the fourth richest country in the world per capita, did not have any papers in health communication. High-income Arab states have the ability to allocate more resources for biomedical research and, accordingly, publish more research on health communications than most of the other Arab countries.

The rise in health communication research in the past few years can be attributed to the rising importance of social media platforms as tools of influence and communication. As such, components of the health sector in the Arab world are investing more in platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to promote healthy practices and improve the physician–patient relationship.28 48 The increasing investment in research and development also contribute to the increase in research output. In addition, the inauguration of the first health communication programme in the Arab world, at the American University of Beirut,8 contributes to raising awareness on the importance of the field of health communication and reflects the placement of Lebanon as the country with the highest output in health communication research.

Conclusion

Health communication is new to the Arab world. This is reflected by the poor research output in the field. Many factors contribute to this decline in research activity; political and economic instability and the rise of wars are key.

In order to change the current status quo, budgetary efforts should be dedicated to fund biomedical research, in general, and health communication research, in specific. Moreover, academic programmes exploring health communication and emphasising the importance and influence of the field in the health sector should be established and promoted in all the states of the Arab world. This will contribute to the advancement of the field and, subsequently, improve public health and individual well-being in the Arab world.

Footnotes

Twitter: @nourmheidly, @DrJawadFares

Contributors: All authors contributed to study design, analysis, and drafting and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. CDC . Health communication basics: centers for disease control and prevention, 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/healthbasics/WhatIsHC.html

- 2. Ayoub F, Fares Y, Fares J. The psychological attitude of patients toward health practitioners in Lebanon. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:452–8. 10.4103/1947-2714.168663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atkin C, Silk K. Health Communication. In: Stacks DW, Salwen MB, eds. Communication theory and methodology. 2nd edn. Routledge, 2009: 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Finnegan J. Health and communication: Medical and public health influences on the research agenda. In: Ray E, Donohew L, eds. Communication and health: systems and applications. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1989: 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kreps GL, Bonaguro EW, JLJRJoC QJ. The history and development of the field of health communication 2003;10:12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fares Y, Fares J, Kurdi M, et al. Physician leadership and hospital ranking: expanding the role of neurosurgeons. Surg Neurol Int 2018;9:199. 10.4103/sni.sni_94_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fares J, Fares MY, Fares Y. Medical schools in times of war: integrating conflict medicine in medical education. Surg Neurol Int 2020;11:5. 10.25259/SNI_538_2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. AUB . AUB launches the new degree in health communication. bridging the educational and professional gap for achieving a better health in Lebanon, the region, and beyond. Lebanon: American University of Beirut, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fares MY, Fares J, Baydoun H, et al. Sport and exercise medicine research activity in the Arab world: a 15-year bibliometric analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2017;3:e000292. 10.1136/bmjsem-2017-000292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adib SM, El Saghir NS, Ammar W. Guidelines for breast cancer screening in Lebanon public health communication. J Med Liban 2009;57:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eid R, Haddad FGH, Kourie HR, et al. Electronic patient-reported outcomes: a revolutionary strategy in cancer care. Future Oncol 2017;13:2397–9. 10.2217/fon-2017-0345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, et al. Breast cancer epidemiology among Lebanese women: an 11-year analysis. Medicina 2019;55:463. 10.3390/medicina55080463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salhab HA, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, et al. Epidemiological study of lung cancer incidence in Lebanon. Medicina 2019;55:217. 10.3390/medicina55060217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares MY, et al. Probing the colorectal cancer incidence in Lebanon: an 11-year epidemiological study. J Gastrointest Cancer 2019;13. 10.1007/s12029-019-00284-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fares J, Kanojia D, Cordero A, et al. Current state of clinical trials in breast cancer brain metastases. Neurooncol Pract 2019;6:392–401. 10.1093/nop/npz003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Afifi Soweid RA, Khawaja M, Salem MT. Religious identity and smoking behavior among adolescents: evidence from entering students at the American University of Beirut. Health Commun 2004;16:47–62. 10.1207/S15327027HC1601_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alhabash S, Almutairi N, Rub MA, et al. Just add a verse from the Quran: effects of religious rhetoric in gain- and Loss-Framed Anti-Alcohol messages with a Palestinian sample. J Relig Health 2017;56:1628–43. 10.1007/s10943-015-0177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bou-Karroum L, El-Jardali F, Hemadi N, et al. Using media to impact health policy-making: an integrative systematic review. Implementation Sci 2017;12:52. 10.1186/s13012-017-0581-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. El-Khoury JR, Shafer A. Narrative exemplars and the celebrity Spokesperson in Lebanese Anti-Domestic violence public service Announcements. J Health Commun 2016;21:935–43. 10.1080/10810730.2016.1177146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Almedawar MM, Nasreddine L, Olabi A, et al. Sodium intake reduction efforts in Lebanon. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2015;5:178–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melki JP, Hitti EA, Oghia MJ, et al. Media exposure, mediated social comparison to idealized images of muscularity, and anabolic steroid use. Health Commun 2015;30:473–84. 10.1080/10410236.2013.867007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Afifi TD, Afifi WA, Acevedo Callejas M, et al. The functionality of communal coping in chronic uncertainty environments: the context of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Health Commun 2018:1–12 (published Online First: 2018/09/22). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kamhawi S, Underwood C, Murad H, et al. Client-centered counseling improves client satisfaction with family planning visits: evidence from Irbid, Jordan. Glob Health Sci Pract 2013;1:180–92. 10.9745/GHSP-D-12-00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Da’ar OB, Yunus F, Md. Hossain N, et al. Impact of Twitter intensity, time, and location on message lapse of bluebird's pursuit of fleas in Madagascar. J Infect Public Health 2017;10:396–402. 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Albalawi YA, Sixsmith J. Exploring the diffusion of tweets designed to raise the road safety agenda in Saudi Arabia. Glob Health Promot 2017;24:5–13. 10.1177/1757975915626111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albalawi Y, Sixsmith J. Agenda setting for health promotion: exploring an adapted model for the social media era. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2015;1:e21. 10.2196/publichealth.5014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alotaibi NM, Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, et al. The current use of social media in neurosurgery. World Neurosurg 2016;88:619–24. 10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Albalawi Y, Sixsmith J. Identifying Twitter influencer profiles for health promotion in Saudi Arabia. Health Promot Int 2017;32:456–63. 10.1093/heapro/dav103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. El Tantawi M, Al-Ansari A, AlSubaie A, et al. Reach of messages in a dental Twitter network: cohort study examining user popularity, communication pattern, and network structure. J Med Internet Res 2018;20:e10781. 10.2196/10781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Elbarazi I, Raheel H, Cummings K, et al. A content analysis of arabic and English newspapers before, during, and after the human papillomavirus vaccination campaign in the United Arab Emirates. Front Public Health 2016;4:176. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aljunaibi A, Abdulle A, Nagelkerke N. Parental weight perceptions: a cause for concern in the prevention and management of childhood obesity in the United Arab Emirates. PLoS One 2013;8:e59923. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mabry RM, Al-Busaidi ZQ, Reeves MM, et al. Addressing physical inactivity in Omani adults: perceptions of public health managers. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:674–81. 10.1017/S1368980012005678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bachleda CL, El Menzhi L. Reducing susceptibility to courtesy stigma. Health Commun 2018;33:771–81. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1312203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hessissen L, Khtar R, Madani A, et al. Improving the prognosis of pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma in developing countries: a Moroccan Society of pediatric hematology and oncology study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1464–9. 10.1002/pbc.24534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kheir N, Awaisu A, Radoui A, et al. Development and evaluation of pictograms on medication labels for patients with limited literacy skills in a culturally diverse multiethnic population. Res Social Adm Pharm 2014;10:720–30. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nour M, Alhajri M, Farag E, et al. How do the first days count? A case study of Qatar experience in emergency risk communication during the MERS-CoV outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1597. 10.3390/ijerph14121597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Asfar T, Schmidt M, Ebrahimi Kalan M, et al. Delphi study among international expert panel to develop waterpipe-specific health warning labels. Tob Control 2019:tobaccocontrol-2018-054718. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sibley A, Han KH, Abourached A, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus infections with today's treatment paradigm–volume 3. 2015;22:21–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maaroufi A, Vince A, Himatt SM, et al. Historical epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in select countries-volume 4. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:8–24. 10.1111/jvh.12762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen DS, Hamoudi W, Mustapha B, et al. Strategies to manage hepatitis C virus infection disease burden-Volume 4. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:44–63. 10.1111/jvh.12759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fares Y, Fares J. Neurosurgery in Lebanon: history, development, and future challenges. World Neurosurg 2017;99:524–32. 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fares J, Salhab HA, Fares MY, et al. Academic Medicine and the Development of Future Leaders in Healthcare. In: Laher I, ed. Handbook of healthcare in the Arab world. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fares MY, Salhab HA, Khachfe HH, et al. Sports Medicine in the Arab world. In: Laher I, ed. Handbook of healthcare in the Arab world. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fares J, Khachfe HH, Fares MY, et al. Conflict Medicine in the Arab world. In: Laher I, ed. Handbook of healthcare in the Arab world. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoteit A. Architectural education in the Arab world and its role in facing the contemporary local and regional challenges 2016;12:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reiche D. War minus the shooting? the politics of sport in Lebanon as a unique case in comparative politics. Third World Q 2011;32:261–77. 10.1080/01436597.2011.560468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Touati KJJoES, Research . Determinants of economic corruption in the Arab countries: dangers and remedies 2014:1.

- 48. Pershad Y, Hangge P, Albadawi H, et al. Social medicine: Twitter in healthcare. JCM 2018;7:121. 10.3390/jcm7060121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]