Abstract

Background:

Falls in older adults are an important issue internationally. They occur from complex interactions between biological, environmental and activity-related factors. As the sexes age differently, there may be sex differences regarding falls. This study aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness of a falls rapid response service (FRRS) in an English ambulance trust and to identify sex differences between patients using the service.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study between December 2018 and September 2020. Patients aged ≥ 60 years who had fallen within the study area were included. The FRRS comprised a paramedic and occupational therapist and responded 07:00–19:00, 7 days per week. Anonymised data regarding age, sex and conveyance were collected for all patients attended by the FRRS and standard ambulance crews. Clinical data regarding fall events were collected from consenting patients attended by the FRRS only.

Results:

There were 1091 patients attended by the FRRS versus 4269 by standard ambulance crews. Patient characteristics were similar regarding age and sex. The FRRS consistently conveyed fewer patients versus standard ambulance crews (467/1091 (42.8%) v. 3294/4269 (77.1%), p = < 0.01). Clinical data were collected from 426/1091 patients attended by the FRRS. In these patients, women were more likely to reside alone than men (181/259 (69.8%) v. 86/167 (51.4%), p = < 0.01), and less likely to experience a witnessed fall (16.2% v. 26.3%, p = 0.01). Women had a higher degree of comorbidity specific to osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, while men were more likely to report a fear of falling score of 0 (35.3% v. 22.7%, p = < 0.01).

Conclusion:

The FRRS is clinically effective regarding falls compared to standard ambulance crews. Sex differences existed between men and women using the FRRS, indicating women are further along the falls trajectory than men. Future research should focus on demonstrating the cost effectiveness of the FRRS and how to better meet the needs of older women who fall.

Keywords: accidental falls, emergency paramedic, older adults, sex

Background

Falls in older adults (adults ≥ 60 years) are an important issue internationally (Bergeron et al., 2006), with significant implications for individuals and healthcare systems. Falls are the primary cause of injury in older adults, are associated with high mortality, morbidity and immobility (Darnell et al., 2012) and result in a reduction in physical activity, functional decline and dependency on institutional care (Dionyssiotis, 2012).

Falls in older adults occur as a result of complex interactions between biological (intrinsic), environmental (extrinsic) and activity-related (behavioural) factors (Inouye et al., 2007). Functional limitations develop over time, and the pathway and magnitude of these limitations (trajectories) are important considerations in relation to falls (Botoseneanu et al., 2016). Differences exist in how the sexes age biologically (Jylhava et al., 2017) and in rates of physical function in later life (Gordon et al., 2017), so sex differences regarding how these factors relate to falls may exist, although the literature remains unclear; Stevens et al. (2012) found women were more likely than men to seek medical care for falls and discuss falls prevention with healthcare providers, while Cameron et al. (2018) reported males were more likely to fall. Other studies report no differences between the sexes (Bor et al., 2017).

In the United Kingdom, ambulance services respond to 300,000–400,000 falls in older adults annually (Close et al., 2002), and falls account for approximately 3% (£980 million) of total National Health Service expenditure (Tian et al., 2013). As the population continues to age, the number of older adults presenting to ambulance services following a fall is likely to increase. Falls prevention is therefore a priority.

Many ambulance services in the United Kingdom have developed falls interventions, including a falls rapid response service (FRRS), comprising a paramedic and occupational therapist. These interventions vary across ambulance services, but are designed to safely avoid conveyance to hospital through enhanced on-scene assessment by a multidisciplinary team.

The impact of an FRRS on conveyance to the emergency department (ED) is unclear, and a lack of evidence exists relating to sex differences between patients using the FRRS. This study aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness of the FRRS, and to decide if ambulance falls interventions should be developed with sex in mind.

Study intervention

This study is described in detail elsewhere (Charlton & Stagg, 2022), but in short, we conducted a cross-sectional study between December 2018 and September 2020. Eligible patients were aged ≥ 60 years, had suffered a fall and resided in Newcastle or Gateshead. The FRRS comprised a paramedic and occupational therapist and responded 07:00–19:00, 7 days per week. It was activated directly by call-takers using the same criteria as standard ambulance crews or by direct referral from crews already in attendance, and did not discriminate accepting referrals with regard to acuity, comorbidity, frailty or injury/pain.

Methods

A fall was defined as an unintentional or unexpected loss of balance resulting in coming to rest on the floor, on the ground or on an object below knee level (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2022). Clinical effectiveness was calculated by measuring the proportion of patients conveyed to hospital compared to those not conveyed for the FRRS versus standard ambulance crews. Sex was dichotomised by male or female sex, to facilitate analysis.

Non-identifiable data regarding age, sex and conveyance were collected for all eligible patients during the first period of contact with the FRRS (index call), irrespective of whether the patient consented to study participation, in line with ethics approval. Data for standard ambulance crew attendance were matched in full to the FRRS eligibility criteria, ensuring both groups were similar at baseline; these data were collected through routine audit.

The FRRS approached eligible patients regarding study participation prior to the cessation of the clinical episode, and received written informed consent from those wishing to participate. Clinical data were collected from these patients using a study-specific case report form; data collected included dwelling, whether they resided alone, characteristics of the fall, comorbidities, fear of falling using an 11-point Likert scale (0 = no fear of falling, 10 = worst fear of falling) (Leung, 2011), frailty at the time of assessment calculated using the Rockwood clinical frailty scale (Church et al., 2020) and polypharmacy (defined as ≥ 4 medications (Ziere et al., 2006)). Case report forms were attached to the ambulance electronic patient care record (ePCR) and retrieved by the research team. It was not possible to collect clinical data for patients attended by standard ambulance crews due to inconsistent ePCR completion and poor data quality.

Statistics

Descriptive data are presented using counts (n) and frequencies (%). Data were categorical and differences between groups analysed using chi squared (X2). A p value of < 0.05 was statistically significant. X2 is presented correct to one decimal place and p-values correct to two decimal places. Data were analysed using R, 3.6.2.

Results

During the study period, 1091 patients were attended by the FRRS versus 4269 by standard crew ambulances. Patient characteristics were similar regarding median age and sex distribution (Table 1). The sex of 24.7% of patients attended by standard crew ambulances was not recorded and unavailable for analysis; there were no missing data for the FRRS.

Table 1.

Sex and age of patients attended by FRRS versus standard ambulance crews.

| FRRS | Standard ambulance crew | |

| Male, n (%) | 440 (40) | 1387 (32.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 661 (60) | 1831 (42.8) |

| Sex unknown, n (%) | N/A | 1051 (24.7) |

| Total (n) | 1091 | 4269 |

| Median age (years) | 84 (range 59–103) | 81 (range 60–104) |

FRRS: falls rapid response service.

Overview of conveyance

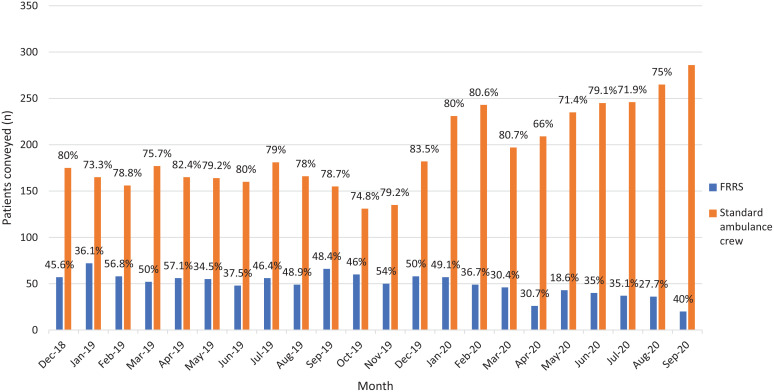

Conveyance to hospital from the index call varied each month, and variance was more pronounced with the FRRS. However, the FRRS consistently conveyed fewer patients than standard crew ambulances (all months p = < 0.01, total conveyed 467/1091 (42.8%) v. 3294/4269 (77.1%), p = < 0.01) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conveyance rate to hospital for patients in each study month for FRRS versus standard ambulance crews.

FRRS: falls rapid response service.

Of patients attended by the FRRS, study patients were more likely to be discharged on scene than those not participating (325/426 (76.2%) v. 299/665 (44.9%)).

Overview of sex differences

Clinical data were collected for 426 consenting patients. Of these, 259 (60.7%) were women (p = < 0.01). Compared to men, women were more likely to reside alone (181/259 (69.8%), p = < 0.01), and less likely to experience a witnessed fall (16.2% v. 26.3%, p = 0.01). Women had a higher degree of comorbidity specific to osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, while men were more likely to report a fear of falling score of 0 versus women (35.3% v. 22.7%, p = < 0.01). No other sex differences reached significance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient clinical characteristics.

| All | Male | Female | X2 (95% CI) | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Participants | 426 (100.0) | 167 (39.3) | 259 (60.7) | 18.5 (11.7–30.5) | < 0.01 |

| Community dwelling | 380 (89.2) | 149 (89.2) | 231 (89.1) | 0.0 (–6.3–5.9) | 0.97 |

| Resides alone | 267 (62.6) | 86 (51.4) | 181 (69.8) | 14.6 (8.9–27.5) | < 0.01 |

| Witnessed fall | 86 (20.1) | 44 (26.3) | 42 (16.2) | 6.4 (2.2–18.2) | 0.01 |

| History of falling | 279 (65.4) | 102 (61.0) | 177 (68.3) | 2.3 (–1.9–16.5) | 0.12 |

| Not known to falls services | 207 (48.5) | 75 (73.5) | 132 (74.5) | 0.0 (–7.3–9.6) | 0.81 |

| Cognitive impairment | 53 (12.4) | 21 (12.5) | 32 (12.3) | 0.0 (–5.9–7.0) | 0.95 |

| Dementia | 24 (5.6) | 9 (5.3) | 15 (5.7) | 0.0 (–4.6–4.7) | 0.86 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 20 (4.6) | 10 (5.9) | 10 (3.8) | 1.0 (–1.9–7.0) | 0.31 |

| Stroke | 82 (19.2) | 31 (18.5) | 51 (19.6) | 0.0 (–6.7–8.4) | 0.77 |

| Diabetes | 92 (21.5) | 42 (25.1) | 50 (19.3) | 2.0 (–2.1–14.1) | 0.15 |

| Mobility dysfunction | 353 (82.8) | 139 (83.2) | 214 (82.6) | 0.0 (–7.0–7.6) | 0.87 |

| Balance disorder | 349 (81.9) | 136 (81.4) | 213 (82.2) | 0.0 (–6.4–8.5) | 0.83 |

| Osteoarthritis | 183 (42.9) | 43 (25.7) | 140 (54.0) | 33.1 (18.9–36.7) | < 0.01 |

| Osteoporosis | 113 (26.5) | 28 (16.7) | 85 (32.8) | 13.4 (7.7–23.7) | < 0.01 |

| Use of walking aids | 336 (78.8) | 134 (80.2) | 202 (77.9) | 0.3 (–5.3–9.1) | 0.57 |

| Blackouts | 34 (7.9) | 9 (5.3) | 25 (9.6) | 2.5 (–1.1–9.1) | 0.1 |

| Vision problems | 210 (49.2) | 83 (49.7) | 127 (49.0) | 0.0 (–8.9–10.3) | 0.88 |

| Incontinence problems | 152 (35.6) | 58 (34.7) | 94 (32.2) | 0.2 (–6.5–11.7) | 0.59 |

| Polypharmacy | 371 (87.0) | 146 (87.4) | 225 (86.8) | 0.0 (–6.2–6.8) | 0.85 |

| Injuries or pain following most recent fall | 188 (44.1) | 72 (43.1) | 116 (44.7) | 0.1 (–8.0–11.0) | 0.74 |

| Fear of falling score of 0 | 118 (27.6) | 59 (35.3) | 59 (22.7) | 8.0 (3.8–21.4) | < 0.01 |

| Conveyed to ED | 101 (23.7) | 36 (31.5) | 65 (25.0) | 2.1 (–2.1–15.3) | 0.14 |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | |||||

| 1 | 4 (0.9) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | 0.1 (–1.7–3.5) | 0.67 |

| 2 | 7 (1.6) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (0.8) | 2.9 (–0.4–6.0) | 0.08 |

| 3 | 13 (3.0) | 6 (3.6) | 7 (2.7) | 0.2 (–2.5–5.1) | 0.59 |

| 4 | 41 (9.6) | 16 (9.6) | 25 (9.7) | 0.0 (–6.1–5.6) | 0.97 |

| 5 | 80 (18.7) | 30 (18.0) | 50 (19.3) | 0.1 (–6.5–8.6) | 0.73 |

| 6 | 148 (34.7) | 59 (35.3) | 89 (34.3) | 0.0 (–8.0–10.3) | 0.83 |

| 7 | 126 (29.5) | 45 (27.0) | 81 (31.2) | 0.8 (–4.7–12.7) | 0.35 |

| 8 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 1.3 (–1.5–2.8) | 0.24 |

| 9 | 4 (0.9) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2.1 (–0.7–4.7) | 0.14 |

| Missing data | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | N/A | N/A |

CI: confidence interval; ED: emergency department.

Discussion

There is limited published evidence on the clinical effectiveness of pre-hospital alternatives to conveyance to hospital for older adults who fall. It is essential to understand the effectiveness of any intervention that is in addition to traditional care provided by emergency ambulance services. This cross-sectional study demonstrates that the FRRS is clinically effective compared to care delivered by standard ambulance crews. Furthermore, there are additional benefits to reducing conveyance to hospital, such as avoiding overcrowding in the ED (Morley et al., 2018), reducing the risk to older adults from being in the ED unnecessarily (disease transmission, delays in receiving medications, etc.) (Richardson, 2006) and improved patient satisfaction (Blodgett et al., 2021).

Among women only, certain characteristics were more common, including residing alone, unwitnessed falls, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis and an increased fear of falling. Women’s increased likelihood of residing alone may be because of longer life expectancy than men, although admittedly, this gap is narrowing (Bennett et al., 2015). Our study confirms previous research that women are more likely to suffer osteoarthritis and osteoporosis than men and experience more severe symptoms (O’Connor, 2007). Both conditions are known to restrict mobility and increase the risk of injury from falling, but the association with increased falls risk is unclear (Ng & Tan, 2013). In this study we observed a significant difference in incidence of both conditions in women compared to men, suggesting that interventional studies in the ambulance setting where falls, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis are the primary outcome are warranted to investigate these differences further.

Limitations

The FRRS was unavailable after 19:00 each day and patients who fall at night may differ from those who fall during the day. This may have implications regarding conveyance decisions.

We were unable to determine the recontact rate for the FRRS, and these data would be important in supporting conclusions regarding clinical effectiveness.

Sex was not recorded in almost a quarter of standard ambulance crew ePCRs, suggesting greater diligence is required in ePCR completion. We were unable to collect clinical data for 61% of patients attended by the FRRS due to non-participation in the study. This additional information would undoubtedly provide a greater understanding of sex differences and falls, and may yield different results. This study was not statistically powered to detect a difference between the sexes, so our findings may not extrapolate to the wider population. Nevertheless, sex differences were identified.

Conclusion

The FRRS is clinically effective and can avoid conveyance to the ED. Sex differences exist between men and women accessing the service, indicating that women are further along the falls trajectory than men and have a different falls profile from them. Future research should focus on demonstrating the cost effectiveness of the FRRS, how the FRRS impacts recontact rates for this population and patient satisfaction with this type of intervention. Future interventions should be developed with sex in mind.

Acknowledgements

We thank the paramedics and occupational therapists working on the FRRS involved in the data collection and for their support for this study.

Author contributions

KC collected the study data and wrote the manuscript. HS analysed the data and provided critical review and comment of the manuscript. EB collected the data and provided critical review and comment of the manuscript. KC acts as the guarantor for this article.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethics

Ethical approval was received from North West – Greater Manchester North West Research Ethics Committee [18/NW/0763] and the Health Research Authority.

Funding

This study was funded by the Academic Health Sciences Network (AHSN) North East and North Cumbria (NENC) and Mangar UK. Neither organisation had any involvement in the design or implementation of this study, or in writing this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Karl Charlton, North East Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust.

Hayley Stagg, North East Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust.

Emma Burrow, North East Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust.

References

- Bennett J. E., Li G., Foreman K., Best N., Kontis V., Pearson C., Hambly P., & Ezzati M. (2015). The future of life expectancy and life expectancy inequalities in England and Wales: Bayesian spatiotemporal forecasting. The Lancet, 386(9989), 163–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron E., Clement J., Lavoie A., Ratte S., Bamvita J. M., Aumont F., & Clas D. (2006). A simple fall in the elderly: Not so simple. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 60(2), 268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett J. M., Robertson D. J., Pennington E., Ratcliffe D., & Rockwood K. (2021). Alternatives to direct emergency department conveyance of ambulance patients: A scoping review of the evidence. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 29(4). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-020-00821-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor A., Matuz M., Csatordai M., Szalai G., Bálint A., Benkő R., Soós G., & Doró P. (2017). Medication use and risk of falls among nursing home residents: A retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 39(2), 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botoseneanu A., Allore H. G., Mendes de Leon C. F., Gahbauer E. A., & Gill T. M. (2016). Sex differences in concomitant trajectories of self-reported disability and measured physical capacity in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(8), 1056–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron E., Bowles S., Marshall E., & Andrew M. (2018). Falls and long-term care: A report from the care by design observational cohort study. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0741-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton K., & Stagg H. (2022). Older adults who fall and predicting conveyance to the emergency department: A cross sectional study in a UK ambulance service. Journal of Paramedic Practice, 14(4), 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Church S., Rogers E., Rockwood K., & Theou O. (2020). A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 393. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01801-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close J. C., Halter M., Elrick A., Brain G., & Swift C. G. (2002). Falls in the older population: A pilot study to assess those attended by London Ambulance Service but not taken to A&E. Age Ageing, 31(6), 488–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell G., Mason S. M., & Snooks H. (2012). Elderly falls: A national survey of UK ambulance services. Emergency Medicine Journal, 29(12), 1009–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionyssiotis Y.. (2012). Analysing the problem of falls among older people. International Journal of General Medicine, 5, 805–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon E. H., Peel N. M., Samanta M., Theou O., Howlett S. E., & Hubbard R. E. (2017). Sex differences in frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Experimental Gerontology, 89, 30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye S. K., Studenski S., Tinetti M. E., & Kuchel G. A. (2007). Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept (see editorial comments by Dr. William Hazzard on pp 794–796). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(5), 780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhava J., Pedersen N. L., & Hagg S. (2017). Biological age predictors. EBioMedicine, 21, 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung S. O. (2011). A comparison of psychometric properties and normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-point Likert scales. Journal of Social Service Research, 37(4), 412–421. [Google Scholar]

- Morley C., Unwin M., Peterson G. M., Stankovich J., & Kinsman L. (2018). Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PloS One, 13(8), e0203316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022). Falls and older people – assessing risk and prevention. Clinical guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg161/resources/falls-in-older-people-assessing-risk-and-prevention-pdf-35109686728645. [PubMed]

- Ng C. T., & Tan M. P. (2013). Osteoarthritis and falls in the older person. Age and Ageing, 42(5), 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M. I. (2007). Sex differences in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 15(Suppl 1), S22–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. B. (2006). Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. The Medical Journal of Australia, 184(5), 213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. A., Ballesteros M. F., Mack K. A., Rudd R. A., DeCaro E., & Adler G. (2012). Gender differences in seeking care for falls in the aged Medicare population. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43(1), 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y., Thompson J., Buck D., & Sonola L. (2013). Exploring the system-wide costs of falls in older people in Torbay. King’s Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ziere G., Dieleman J. P., Hofman A., Pols H. A., Van Der Cammen T. J. M., & Stricker B. C. (2006). Polypharmacy and falls in the middle age and elderly population. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 61(2), 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]