Abstract

Objectives:

Despite significant declines in cigarette smoking during the past decade, other tobacco products gained popularity among middle and high school students. This study examined temporal trends in exclusive and concurrent use of tobacco products among middle and high school students in the United States from 2011 through 2020.

Methods:

We used multiple annual datasets from the National Youth Tobacco Survey from 2011 through 2020 (N = 193 350) to examine trends of current (past 30 days) exclusive, dual, and poly use of tobacco products (ie, cigarettes, electronic cigarettes [e-cigarettes], cigars, hookahs, and smokeless tobacco). We used joinpoint regression models to calculate log-linear trends in annual percentage change (APC).

Results:

During 2011-2020, exclusive use of any tobacco product decreased significantly, except for e-cigarettes, which increased significantly at an APC of 226.8% during 2011-2014 and 14.6% during 2014-2020. This increase was more pronounced among high school students (APC = 336.6% [2011-2014] and 15.7% [2014-2020]) than among middle school students (APC = 10.4% [2014-2020]) and among male students (APC = 252.8% [2011-2014] and 14.8% [2014-2020]) than among female students (APC = 13.6% [2014-2020]). During 2011-2020, we also found upward trends in dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes (APC = 17.3%). Poly use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and any other tobacco products increased significantly at an APC of 57.1% during 2011-2014.

Conclusions:

The emergence of new tobacco products such as e-cigarettes in the US market has shifted the landscape of tobacco use among adolescents in the last decade toward poly product use, in which e-cigarettes are a prominent component. Our findings underscore the increasing complexity of tobacco use among adolescents in the United States and the need for strong policies and regulations adapted to evolving trends in cigarette and noncigarette tobacco products.

Keywords: tobacco, youth, trends

Tobacco use, which typically begins during adolescence, 1 is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States. 2 Cigarette smoking was the most common tobacco product used by middle and high school students in the United States until the last decade, when this quickly started to change.2,3 From 2011 through 2020, current (past 30 days) cigarette smoking decreased from 4.3% to 1.6% among middle school students and from 15.8% to 4.6% among high school students.2-4

Progress in reducing cigarette smoking has been upended in the last decade by the introduction of new tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) and hookahs.2,5 So while cigarette smoking decreased dramatically among middle and high school students in the United States from 2011 through 2020, the prevalence of current use of any tobacco product decreased only slightly, from 24.2% to 23.6% among high school students and from 7.5% to 6.7% among middle school students.2,3 Moreover, a large proportion of middle and high school students has become poly tobacco users (users of ≥2 tobacco products).6,7 For example, in 2020, three in 100 middle school students and 8 in 100 high school students reported current dual or poly use of tobacco products. 2 The use of multiple tobacco products exposes young people to early onset of nicotine dependence, adverse cognitive and psychological outcomes, and tobacco-related diseases later in life.7-9

These changes in tobacco use among young people require proper documentation and understanding of tobacco use trends to devise effective strategies to address them. A good starting point would be to conduct comprehensive surveillance of tobacco products currently available on the market and describe the dynamic trends in tobacco product use among young people in the United States. Several national reports have started such efforts by examining tobacco use trends among middle and high school students.2,4,10,11 Although informative, the existing literature lacks information about turning points in trends in exclusive and concurrent tobacco use in the past decade. From a program-planning and policy perspective, examining these trends is essential to better understand the impact of the tobacco market evolution on tobacco use among young people and the effectiveness or failure of interventions and policies to address these trends. Doing so can help improve future interventions and policies tailored toward populations with distinct tobacco use patterns.

Here, we examined trends in exclusive and concurrent (dual and poly) use of cigarettes and noncigarette tobacco products from 2011 through 2020 using National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) data. We also examined trends in using these products overall, by sex, by race and ethnicity, and among middle and high school students. We used the National Cancer Institute’s joinpoint software to describe changes in the current use of tobacco products that middle and high school students in the United States used individually and concurrently during the past decade. Joinpoint regression is a rigorous statistical procedure that groups the data into time segments to identify changes in trends and uses time-course data to identify the time point(s) at which the trend significantly changes. 12 Understanding these changes and the time points at which they occur is crucial for monitoring tobacco control interventions and challenges that could hamper progress or success in reducing tobacco use among young people. Moreover, the evolving market of tobacco products and innovations in product features and designs underlie the importance of tracking trends in all tobacco products used by young people to guide and evaluate regulations and policies at the local, state, and national levels.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used multiple annual datasets from the NYTS from 2011 through 2020 (N = 193 350). 1 The NYTS is a voluntary, school-based, self-administered cross-sectional annual survey that collects information on key tobacco indicators, such as behaviors and attitudes from students in middle school (grades 6-8) and high school (grades 9-12), and provides national estimates on these indicators. Participants were aged 9 to 19 years. The NYTS uses a stratified, 3-stage cluster sample design to produce a nationally representative sample of middle and high school students in the United States. After being conducted via paper-and-pencil questionnaires since its inception in 1999, the NYTS began using electronic data collection methods in 2019. A detailed description of the NYTS design, questionnaires, and data collection can be found elsewhere. 1

Measures

Outcome variables

We assessed patterns and trends in exclusive and concurrent tobacco use among middle and high school students for 6 tobacco products: cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, smokeless tobacco, and other tobacco products. We combined data on the use of pipes, bidis, roll-your-own, heated tobacco products, and kreteks into the category “other tobacco products” because of small sample sizes. We included only students who reported the use of any of these products in the past 30 days. We excluded participants with missing responses on all tobacco products. Study analysis samples ranged from 3190 (17.1% of students) in 2011 to 2209 (16.0% of students) in 2020.

Current tobacco use was defined as using ≥1 of the 6 tobacco products on ≥1 day in the past 30 days. Any current tobacco use was further examined as 3 categories: exclusive use, defined as current use of only 1 tobacco product; dual use, defined as current use of only 2 tobacco products; and poly use, defined as current use of ≥3 tobacco products.

We then categorized current exclusive, dual, and poly use into several categories based on prior research classification 10 and the most frequently occurring combinations (Figure 1). We examined current exclusive use as 6 mutually exclusive categories: current use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, smokeless tobacco, and 1 other tobacco product.

Figure 1.

Categories used to define current tobacco use among middle and high school students in the United States, National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020. In the poly use category, “other” refers to cigars, hookahs, smokeless, pipes, bidis, roll-your-own, HTPs, and kreteks. Abbreviations: e-cigarettes, electronic cigarettes; HTP, heated tobacco product. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1

We examined 10 categories of current dual use: (1) cigarettes and e-cigarettes, (2) cigarettes and hookahs, (3) cigarettes and cigars, (4) cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, (5) cigarettes and other (defined as tobacco products not including cigarettes, hookahs, cigars, or smokeless tobacco), (6) e-cigarettes and hookahs, (7) e-cigarettes and cigars, (8) e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, (9) e-cigarettes and other, and (10) any 2 tobacco products not including cigarettes or e-cigarettes.

We examined 4 categories of current poly use: (1) cigarettes + e-cigarettes + ≥1 other tobacco product, (2) cigarettes + ≥2 other tobacco products (not including e-cigarettes), (3) e-cigarettes + ≥2 other tobacco products (not including cigarettes), and (4) ≥3 tobacco products not including cigarettes or e-cigarettes. For poly use, we combined data on the use of cigars, hookahs, smokeless tobacco, pipes, bidis, roll-your-own, heated tobacco products, and kreteks into the category “other tobacco products” because of small sample sizes.

Covariates

We selected the covariates in this study based on previously published reports by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)2-4,13: sex (male or female), race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black or African American, non-Hispanic Other [including Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander], or non-Hispanic White), and school level (middle or high school).

Statistical Analysis

We used joinpoint regression software version 4.9.0.0 (National Cancer Institute) to analyze temporal trends in the annual prevalence of tobacco product use (exclusive and concurrent use) during 2011-2020. Joinpoint regression groups data into time segments to identify years in which a significant change in trend occurs. 14 For each time segment, joinpoint analysis provides an estimate of the annual percentage change (APC) in prevalence during that period, and it indicates whether the APC is significantly different from zero (indicating no trend).14,15 We performed stratified joinpoint regression analyses for all sex, race, and school levels for tobacco use combinations, providing the SE for each annual prevalence estimate. Additionally, we examined overall linear trends from survey regression models with a continuous term for the year. All analyses were weighted to account for the complex survey design and adjusted for nonresponse using SAS/STAT version 14.2 (SAS Institute Inc) survey procedures (PROC SURVEYFREQ). We considered P < .05 to be significant. Because the NYTS is a public use database, our study did not require institutional review board approval.

Results

Overall Trend Analysis

Among current tobacco users, we observed an increase in exclusive use of tobacco products at an APC of 6.4% during 2015-2020; however, dual use decreased at an APC of −3.8% during 2011-2020, and poly use decreased at an APC of −15.9% during 2017-2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of any current tobacco use among middle and high school students overall from 2011 through 2020, National Youth Tobacco Survey. Linear trend: exclusive (49.7% to 63.9%; P = .002); dual (24.7% to 19.5%; P = .007); poly (25.6% to 16.6%; P = .06). Significance determined by joinpoint regression; P < .05 considered significant. Abbreviation: APC, annual percentage change. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1

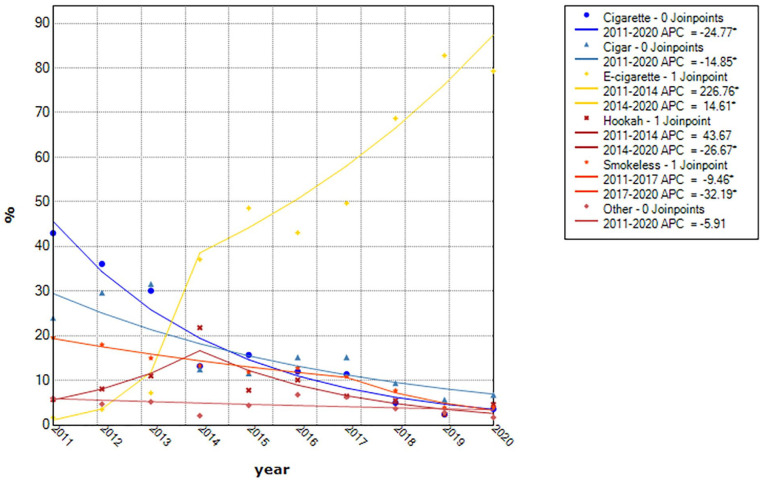

Exclusive use of cigarettes (APC = −24.8% during 2011-2020), cigars (APC = −14.9% during 2011-2020), hookahs (APC = −26.7% during 2014-2020), and smokeless tobacco (APC = −9.5% during 2011-2017 and −32.2% during 2017-2020) decreased overall, while exclusive use of e-cigarettes increased at an APC of 226.8% during 2011-2014 and 14.6% during 2014-2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of current exclusive tobacco use among middle and high school students overall from 2011 through 2020, National Youth Tobacco Survey. Linear trend: cigarette (43.0% to 3.6%; P < .001); cigar (24.0% to 6.8%; P = .01); electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) (1.7% to 79.3%; P < .001); hookahs (5.7% to 4.6%; P = .06); smokeless (19.6% to 3.9%; P < .001); other (6.0% to 1.7%; P = .13). Significance determined by joinpoint regression; P < .05 considered significant. Abbreviation: APC, annual percentage change. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1

Whereas dual use of cigarettes and tobacco products such as hookahs (APC = −40.0% during 2014-2020), cigars (APC = −25.5% during 2011-2020), and smokeless tobacco (APC = −15.2% during 2011-2020) decreased, dual use of e-cigarettes with cigarettes (APC = 17.3% during 2011-2020), cigars (APC = 19.5% during 2014-2020), and smokeless tobacco (APC = 14.8% during 2014-2020) increased (Figure 4). Among current poly users, poly use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and ≥1 other tobacco product increased significantly at an APC of 57.1% during 2011-2014 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of current dual tobacco use among middle and high school students overall from 2011 through 2020, National Youth Tobacco Survey. Linear trend: cigarette + electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) (3.4% to 27.8%; P < .001); cigarette + hookahs (6.0% to 0.3%; P < .001); cigarette + cigar (38.7% to 3.9%; P < .001); cigarette + smokeless tobacco (21.6% to 2.5%; P = .01); cigarette + other (5.5% to 0.4%; P = .09); e-cigarette + hookah (0.2% to 13.4%; P = .06); e-cigarette + cigar (0.4% to 20.8%; P < .001); e-cigarette + smokeless tobacco (1.1% to 17.1%; P = .003); e-cigarette + other (0.1% to 3.7%; P = .001); 2 tobacco products not including cigarette or e-cigarette (23.1% to 10.0%; P = .04). Significance determined by joinpoint regression; P < .05 considered significant. Abbreviation: APC, annual percentage change. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1

Figure 5.

Prevalence of current poly tobacco use among middle and high school students overall from 2011 through 2020, National Youth Tobacco Survey. Linear trend: cigarette + electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) + ≥1 other tobacco product (13.9% to 62.1%; P = .01); cigarette + ≥2 other tobacco products not including e-cigarette (72.6% to 7.5%; P = .002); e-cigarette + ≥2 other tobacco products not including cigarette (1.8% to 24.8%; P = .01); ≥3 tobacco products not including cigarette or e-cigarette (11.7% to 5.6%; P = .18). Significance determined by joinpoint regression; P < .05 considered significant. Abbreviation: APC, annual percentage change. Data source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1

Trend Analysis by Sex

Current use of each exclusive tobacco product except e-cigarettes decreased during 2011-2020. However, we observed an increase in the use of only e-cigarettes among female students (APC = 13.6%) and male students (APC = 14.8%) during 2014-2020. While dual use of cigarettes and hookahs increased (APC = 76.2%) during 2011-2014 and then decreased (APC = −44.5%) during 2014-2020 among female students, their dual use decreased at an APC of −31.3% during 2011-2020 among male students. Dual cigarette and cigar use decreased among female students (APC = −23.4%) and male students (APC = −28.2%) during 2011-2020. However, dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes (APC = 18.5% among female students and 13.1% among male students during 2011-2020) and e-cigarettes and cigars (APC = 42.5% among female students during 2013-2020; APC = 18.2% among male students during 2011-2020) increased among male and female students.

Trend Analysis by Race

During 2011-2020, exclusive use of cigarettes and cigars decreased among all racial and ethnic groups: APC = −25.4% for cigarettes and −17.1% for cigars among non-Hispanic White students; APC = −30.3% for cigarettes and −14.6% for cigars among non-Hispanic Other students; APC = −25.3% for cigarettes and −15.7% for cigars among Hispanic students; and APC = −23.6% for cigarettes and −7.5% for cigars among non-Hispanic Black students. Exclusive use of hookahs decreased at an APC of −35.3% among non-Hispanic White students and at an APC of −23.3% among Hispanic students only during 2014-2020. Exclusive use of smokeless tobacco decreased at an APC of −7.6% during 2011-2016 and continued to decrease at an APC of −30.2% during 2016-2020 among non-Hispanic White students. It also decreased among non-Hispanic Other (APC = −17.5%) and Hispanic (APC = −10.8%) students during 2011-2020. However, e-cigarette use increased significantly among all races except non-Hispanic Other during 2011-2020.

Dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes increased at an APC of 15.5% during 2011-2020 among non-Hispanic White students, 15.6% among Hispanic students, and 22.5% among non-Hispanic Black students. E-cigarette and smokeless tobacco use increased at an APC of 23.3% among non-Hispanic White students during 2011-2020 and at an APC of 74.3% among Hispanic students during 2011-2016. During 2011-2020, e-cigarette and cigar use increased among all racial and ethnic groups except non-Hispanic White students (APC = 28.0% among non-Hispanic Black students; APC = 35.1% among Hispanic students; APC = 25.6% among non-Hispanic Other students). During 2011-2020, the use of e-cigarettes and 1 other tobacco product, not including cigarettes, cigars, hookahs, and smokeless tobacco, increased at an APC of 36.9% among non-Hispanic White students, 40.5% among Hispanic students, and 24.5% among non-Hispanic Black students. However, it decreased at an APC of −32.6% during 2018-2020 among non-Hispanic Other students.

Trend Analysis by School Level

Among current exclusive use, we found decreases in the use of cigarettes (APC = −22.9% among middle school students and −24.5% among high school students during 2011-2020), cigars (APC = −15.9% among middle school students and −14.0% among high school students during 2011-2020), hookahs (APC = −23.3% among middle school students and −27.1% among high school students during 2014-2020), and smokeless tobacco (APC = −11.3% among middle school students during 2011-2020; APC = −8.6% during 2011-2016 and −28.7% during 2016-2020 among high school students). However, e-cigarette use increased among middle school students (APC = 10.4% during 2014-2020) and high school students (APC = 336.6% during 2011-2014 and 15.7% during 2014-2020).

During 2011-2020, dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes increased at an APC of 14.9% among middle school students and 18.2% among high school students. Similarly, dual use of e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco trended upward (APC = 78.8% among middle school students during 2011-2016; APC = 22.2% among high school students during 2011-2020). However, dual use of cigarettes and cigars (APC = −31.7% among middle school students and −24.8% among high school students during 2011-2020) and cigarettes and hookahs (APC = −15.3% among middle school students during 2011-2020; APC = −41.7% among high school students during 2014-2020) trended downward.

Discussion

This nationally representative study revealed a downward temporal trend in the exclusive use of any tobacco product from 2011 through 2020, except for e-cigarettes, which increased significantly overall and by sex, by race and ethnicity, and among middle and high school students. For dual and multiple tobacco product use, we observed an upward trend in dual use of e-cigarettes with other tobacco products, such as cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco. In particular, dual use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes trended upward among middle and high school students and male students, as well as Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Black students. In contrast, we found downward trends in dual use of cigarettes and other tobacco products (except for e-cigarettes). These results are consistent with previous studies that investigated the use of multiple tobacco products among young people in the United States by accessing national datasets such as the Monitoring the Future survey15,16 and the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. 17 Although previous studies did not investigate concurrent tobacco use in detail, as our study did, they found similar changes in poly tobacco use among middle and high school students as well as male and female students of different races.15-17 Our findings underscore the increasing complexity of tobacco use among middle and high school students in the United States and the need to understand the trends and drivers of tobacco use patterns to plan for effective responses.

Our results showed that the use of noncigarette tobacco products changed significantly during the past decade, with some noticeable trends. For example, in 2014, e-cigarette use increased sharply among middle and high school students; this increase parallels the emergence of pod-based e-cigarettes with higher nicotine content levels (eg, JUUL). 18 Several features have helped this prefilled cartridge-based e-cigarette become predominant among young people, including the variety of flavors, design, and massive advertisement primarily through social media. 19 Despite several efforts to control e-cigarette use among young people, we observed an increase in exclusive and poly use of e-cigarettes with other tobacco products. These efforts started when JUUL Labs, Inc, removed all flavored products except mint and menthol from retail stores in late 2018,20,21 which was followed by the removal of mint-flavored pods in late 2019. 21 The US Food and Drug Administration issued a new policy on January 2, 2020, that banned any flavored cartridge-based e-cigarette product other than menthol and tobacco-flavored cartridges but did not restrict the sale of tobacco- and menthol-flavored cartridges, open-system e-cigarettes, or disposable e-cigarettes.21,22 However, because of these restrictions, young people switched to menthol products or fruit-flavored disposable e-cigarettes that were unrestricted and easily accessible in appealing flavors.20,21,23 Using popular and exotic flavors is one of the main strategies of tobacco product industries to get young nicotine-naïve people to try these products,24-26 while nicotine ensures that many become lifelong customers.27,28 Nevertheless, the US Congress passed a federal Tobacco 21 law on December 20, 2019, raising the minimum legal age for the sale of tobacco products from 18 to 21 nationwide. 29 These policies, which aim to limit population harm of tobacco products, should be enacted as part of a comprehensive approach that includes smoke-free laws, pricing strategies, retail display bans, health warnings, plain packaging, flavor ingredient restrictions, and prohibitions on internet sales.29,30 Policies should also consider the totality of evidence and potential side effects to curb the ongoing epidemic of nicotine addiction among young people. 31

We found that not only did exclusive e-cigarette use increase during the past decade but dual and poly use of e-cigarettes with other tobacco products also increased. For example, the results showed that the most common product combinations were e-cigarettes and cigarettes, e-cigarettes and cigars, and e-cigarettes and smokeless tobacco and that use of these combinations increased among middle and high school students during the study period. The popularity of e-cigarettes among young people is likely making them the newest start-up product on the cascade leading to other nicotine products.32,33 For example, several studies based on the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, which is the largest tobacco-related population cohort study conducted in the United States, showed that uptake of e-cigarettes is increasingly taking place among never-smoking adolescents and that many of these adolescents move into patterns of dual tobacco use.34,35 Long-term prospective studies are needed to explore the initiation and continuation of cigarette and other tobacco use among young, established users of e-cigarettes. It is also imperative to monitor tobacco use among young people and interactions between multiple tobacco products and evaluate the appropriate prevention strategies.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the NYTS is a school-based sample that may not adequately represent all school-aged people, especially those who are homeschooled or dropped out of school. 6 However, the percentage of students aged 10 to 17 years enrolled in traditional schools in the United States ranged from 97% to 98% in the past decade, according to the US Census Bureau.36-45 Second, the data did not allow adequate assessment of other tobacco products (ie, pipes, bidis) because of the small number of people using these products, which led to combining them into a single group. Finally, we did not assess the frequency and quantity of exclusive, dual, and poly tobacco product use. Thus, we cannot determine the intensity of use among exclusive, dual, and poly users and its association with shifting trends of tobacco product use. 9 Despite these limitations, our study documents the dynamics of the trends of tobacco products used by middle and high school students in the past decade by using comprehensive and complete national data that allow the analysis of trends in the use of various tobacco products by this population.

Conclusions

Findings from this study highlight the increasing complexity of tobacco use among middle and high school students in the United States and the need to understand the trends and drivers of tobacco use patterns for effective interventions. Tobacco control policies should adapt to the changes in tobacco use and the interaction between multiple tobacco products and their potential of leading to use of multiple tobacco products, which may hamper decades of success in reducing tobacco-related morbidity and mortality.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The following supplementary materials are available upon request from the corresponding author: (1) tables on the prevalence, by year, of current use of any tobacco product, exclusive use, dual use, and poly use among middle and high school students in the National Youth Tobacco Surveys from 2011 through 2020 overall, by sex (male and female), by school level (middle school and high school), and by race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Other, and non-Hispanic White); and (2) line graphs showing trends in the prevalence of current use of any tobacco product, exclusive use, dual use, and poly use among middle and high school students in the National Youth Tobacco Surveys from 2011 through 2020, by sex (male and female), race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic Other, and non-Hispanic White), and school level (middle school and high school).

Availability of Data: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in repository at https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/data/index.html.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Rime Jebai, MPH  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9265-1323

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9265-1323

Olatokunbo Osibogun, PhD  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8902-4356

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8902-4356

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS). Published 2020. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/%0Asurveys/nyts/index.htm

- 2.Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1881-1888. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TW, Gentzke A, Sharapova S, Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Jamal A.Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):629-633. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(6):157-164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruz TB, McConnell R, Low BW, et al. Tobacco marketing and subsequent use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes, and hookah in adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(7):926-932. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE.Youth tobacco product use in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):409-415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez Y, Creamer ML, Trivers KF, et al. Patterns of tobacco use and nicotine dependence among youth, United States, 2017-2018. Prev Med. 2020;141:106284. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Toukhy S, Sabado M, Choi K.Trends in tobacco product use patterns among US youth, 1999-2014. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(6):690-697. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soneji S, Sargent J, Tanski S.Multiple tobacco product use among US adolescents and young adults. Tob Control. 2016;25(2):174-180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR.Patterns of current use of tobacco products among US high school students for 2000-2012—findings from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(1):54-60.e.9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tam J.E-cigarette, combustible, and smokeless tobacco product use combinations among youth in the United States, 2014-2019. Preprint. Posted online June 14, 2020. medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.20112581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Lin Y, Yang M, Zhang L.Statistics and pitfalls of trend analysis in cancer research: a review focused on statistical packages. J Cancer. 2020;11(10):2957-2961. doi: 10.7150/jca.43521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang TW, Trivers KF, Marynak KL, et al. Harm perceptions of intermittent tobacco product use among US youth, 2016. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(6):750-753. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN.Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335-351. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meza R, Jimenez-Mendoza E, Levy DT.Trends in tobacco use among adolescents by grade, sex, and race, 1991-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2027465. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975-2014: Vol II, College Students and Adults Ages 19-55. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2015. Accessed November 15, 2021. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Lung Association. Overall tobacco trends. Published 2020. Accessed November 15, 2021. https://www.lung.org/research/trends-in-lung-disease/tobacco-trends-brief/overall-tobacco-trends

- 18.Goniewicz ML, Boykan R, Messina CR, Eliscu A, Tolentino J.High exposure to nicotine among adolescents who use JUUL and other vape pod systems (“pods”). Tob Control. 2019;28(6):676-677. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fadus MC, Smith TT, Squeglia LM.The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;201:85-93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali FRM, Diaz MC, Vallone D, et al. E-cigarette unit sales, by product and flavor type—United States, 2014-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1313-1318. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz MC, Donovan EM, Schillo BA, Vallone D.Menthol e-cigarette sales rise following 2020 FDA guidance. Tob Control. 2021;30(6):700-703. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint [news release]. Published January 2, 2020. Accessed July 4, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- 23.Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Neff LJ, et al. Disposable e-cigarette use among US youth—an emerging public health challenge. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1573-1576. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2033943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran MB, Heley K, Baldwin K, Xiao C, Lin V, Pierce JP.Selling tobacco: a comprehensive analysis of the US tobacco advertising landscape. Addict Behav. 2019;96:100-109. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishen AS, Hu HF, Spivak AL, Venger O.The danger of flavor: e-cigarettes, social media, and the interplay of generations. J Bus Res. 2021;132:884-896. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanski SE. Marketing and advertising of e-cigarettes and pathways to prevention. In: Walley SC, Wilson K, eds. Electronic Cigarettes and Vape Devices: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinicians and Health Professionals. Springer; 2021:105-114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-78672-4_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell C, McKeganey N, Dickson T, Nides M.Changing patterns of first e-cigarette flavor used and current flavors used by 20,836 adult frequent e-cigarette users in the USA. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):1-14. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0238-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Glasser AM, et al. Association of flavored tobacco use with tobacco initiation and subsequent use among US youth and adults, 2013-2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913804. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marynak K, Mahoney M, Williams K-AS, Tynan MA, Reimels E, King BA.State and territorial laws prohibiting sales of tobacco products to persons aged <21 years—United States, December 20, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(7):189-192. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6907a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapman S, Bareham D, Maziak W.The gateway effect of e-cigarettes: reflections on main criticisms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(5):695-698. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preventing Tobacco Addiction Foundation. Tobacco 21 statement on federal law. Published December 20, 2019. Accessed January 11, 2022. https://tobacco21.org/tobacco-21-statement-on-federal-law

- 32.Chan GCK, Stjepanović D, Lim C, et al. Gateway or common liability? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies of adolescent e-cigarette use and future smoking initiation. Addiction. 2021;116(4):743-756. doi: 10.1111/add.15246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khouja JN, Suddell SF, Peters SE, Taylor AE, Munafò MR.Is e-cigarette use in non-smoking young adults associated with later smoking? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tob Control. 2021;30(1):8-15. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Osibogun O, Bursac Z, Maziak W.E-cigarette use and regular cigarette smoking among youth: Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study (2013-2016). Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(5):657-665. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lea Watkins S, Glantz SA, Chaffee BW.Association of noncigarette tobacco product use with future cigarette smoking among youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(2):181-187. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2011—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2011/demo/school-enrollment/p20-571.html

- 37.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2012—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2012/demo/school-enrollment/2012-cps.html

- 38.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2013—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/demo/school-enrollment/2013-cps.html

- 39.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2014—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2014/demo/school-enrollment/2014-cps.html

- 40.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2015—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2015/demo/school-enrollment/2015-cps.html

- 41.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2016—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/school-enrollment/2016-cps.html

- 42.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2017—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2017/demo/school-enrollment/2017-cps.html

- 43.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2018—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/school-enrollment/2018-cps.html

- 44.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2019—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2019/demo/school-enrollment/2019-cps.html

- 45.US Census Bureau. School enrollment in the United States: October 2020—detailed tables. Accessed April 8, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/school-enrollment/2020-cps.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-phr-10.1177_00333549221103812 for Temporal Trends in Tobacco Product Use Among US Middle and High School Students: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2020 by Rime Jebai, Olatokunbo Osibogun, Wei Li, Prem Gautam, Zoran Bursac, Kenneth D. Ward and Wasim Maziak in Public Health Reports