RESUMEN

Objetivo.

Informar los resultados de la ablación con catéter de taquicardia ventricular (TV) en la cardiopatía isquémica (CI) e identificar los factores de riesgo asociados a la recurrencia en un centro mexicano.

Materiales y métodos

. Se realizó una revisión retrospectiva de los casos de ablación de TV ejecutados en nuestro centro desde 2015 hasta 2022. Se analizó por separado las características de los pacientes y las de los procedimientos y se determinaron los factores asociados a la recidiva.

Resultados

. Se realizaron 50 procedimientos en 38 pacientes (84% varones; edad media 58,1 años). La tasa de éxito agudo fue del 82%, con un 28% de recurrencia. Sexo femenino (OR 3,33, IC 95% 1,66-6,68, p=0,006); fibrilación auricular (OR 3,5, IC 95% 2,08-5,9, p=0,012); tormenta eléctrica (OR 2.4, IC 95% 1.06-5.41, p =0,045); la clase funcional mayor que II (OR 2,86, IC 95% 1,34-6,10, p=0,018) fueron factores de riesgo para recurrencia y la presencia de TV clínica en el momento de la ablación (OR 0,29, IC 95% 0,12- 0,70, p=0,004) y el uso de más de dos técnicas de mapeo (OR 0,64, IC 95% 0,48 - 0,86, p=0,013) fueron factores protectores.

Conclusiones.

La ablación de taquicardia ventricular en cardiopatía isquémica ha tenido buenos resultados en nuestro centro. La tasa de recurrencia es similar a lo reportado por otros autores y existen algunos factores asociados a ella.

Palabras clave: Taquicardia Ventricular, Cardiopatía Isquémica, Ablación con Catéter

ABSTRACT

Objective

. To report the results of ventricular tachycardia (VT) catheter ablation in ischemic heart disease (IHD), and to identify risk factors associated with recurrence in a Mexican center.

Materials and methods

. We made a retrospective review of the cases of VT ablation performed in our center from 2015 to 2022. We analyzed the characteristics of the patients and those of the procedures separately and we determined factors associated with recurrence.

Results

. Fifty procedures were performed in 38 patients (84% male; mean age 58.1 years). Acute success rate was 82%, with a 28% of recurrences. Female sex (OR 3.33, IC 95% 1.66-6.68, p=0.006), atrial fibrillation (OR 3.5, IC 95% 2.08-5.9, p=0.012), electrical storm (OR 2.4, IC 95% 1.06-5.41, p=0.045), functional class greater than II (OR 2.86, IC 95% 1.34-6.10, p=0.018) were risk factors for recurrence and the presence of clinical VT at the time of ablation (OR 0.29, IC 95% 0.12-0.70, p=0.004) and the use of more than 2 techniques for mapping (OR 0.64, IC 95% 0.48-0.86, p=0.013) were protective factors.

Conclusions

. Ablation of ventricular tachycardia in ischemic heart disease has had good results in our center. The recurrence is similar to that reported by other authors and there are some factors associated with it.

Keywords: Ventricular Tachycardia, Ischemic Heart Disease, Catheter Ablation

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is one of the leading causes of heart failure worldwide and is the most frequent cause of ventricular tachycardia (VT) in patients with structural heart disease 1; in this context, reentry is the most common mechanism of VT. In these patients the dense scar and borderline tissue are common findings, being these areas the most relevant in reentry circuits 1,2.

In 1999 the MUSTT trial demonstrated that catheter ablation reduces VT recurrence in patients with IHD 3. Subsequent studies corroborated these findings and reaffirmed that catheter ablation reduces recurrence of VT 4,5 and also reduced the composite of mortality, hospitalizations, and discharges of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) 6,7. Nowadays, catheter ablation is the procedure of choice in patients with structural heart disease and recurrent VT despite optimal medical treatment and in patients with multiple ICD discharges 1,2,8,9. It should be noted that VT ablation in the presence of structural heart disease is a very complex procedure that requires an electroanatomic mapping system 10.

Because IHD in our country is highly prevalent, as it is worldwide, we considered appropriate to report our experience in VT ablation in patients with IHD and to determine which factors are associated with VT recurrence.

Materials and methods

We performed a descriptive, retrospective study of patients older than 18 years diagnosed with IHD who underwent electrophysiological study and catheter ablation from January 2015 through April 2022 at the Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chavez in México city.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of IHD and VT documented by 12-lead electrocardiogram or ICD review, with indication of ablation according to current international guidelines and with informed consent. Patients were cataloged as having IHD if they had a history of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), with or without revascularization, significant coronary disease (diagnosed by coronary angiography or by tomography) or if they had evidence of ischemia or fibrosis with an ischemic pattern in other imaging studies (cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or nuclear medicine studies). Patients without evidence of ischemia or without fibrosis with ischemic pattern or with mixed pattern were excluded. Clinical VT was defined as the VT documented before ablation on a 12-lead ECG or diagnosed after ICD revision. Electrical storm was defined as the presence of 3 or more episodes of sustained VT spaced at least 5 minutes apart in a 24-hour period.

All electrophysiological studies were performed using an electroanatomical mapping system CARTO (Biosense - Webster, Diamond Bar, California) or ENSITE (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota), all studies were performed either with general anesthesia or sedation. In all cases, a decapolar catheter was placed in the coronary sinus and a quadripolar catheter in the right ventricle apex (RVA). Access to the left ventricle (LV) was performed by retro-aortic way or by transseptal puncture. If necessary, the epicardial approach was obtained in the conventional manner previously described 11. Unfractionated heparin infusion was administered to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) between 250 to 350 seconds.

At the beginning of the procedure, we performed pacing maneuvers from the catheter positioned at the RVA. We used conventional mapping techniques, if the VT was hemodynamically tolerated, we performed activation mapping or entrainment, but if it was not hemodynamically tolerated, substrate-guided mapping or pace mapping was used. The combination of these techniques was performed at the discretion of the operator.

Regarding the ablation, we employed techniques previously described 1,2 such as homogenization, dechanelling or linear ablation to achieve an adequate substrate modulation, the combination of these techniques was performed according to the operator discretion. All ablations were performed using an irrigated radiofrequency catheter. The radiofrequency application was guided by impedance drop (>10 ohms) for a variable time, between 20 and 60 seconds at the discretion of the operator.

After the ablation, we perform the same stimulation maneuvers from the RVA catheter, an ablation was classified as successful if at the end of the procedure it was not possible to induce the clinical VT. A major complication was defined as one that prolonged the hospital stay and/or required another procedure to solve it. Recurrence was defined as the reappearance of clinical VT for more than 30 seconds (with the same morphology and/or the same cycle length) either by a 12-lead ECG, 24-hour Holter or by ICD review.

After VT ablation, patients discharge depended on their clinical condition, and could be discharged the day after the ablation or remaining hospitalized until all their clinical problems were resolved. After discharge, a first assessment was made 3 months, and then every 6 or 12 months, all patients with ICDs received a follow-up every 6 months. A 24-hour Holter study were performed according to the clinical judgment of the treating physician.

Statistical analysis

Being aware that the recurrence of tachycardia greatly impacts the patient's prognosis. After the follow-up, we studied which variables were associated with recurrence. To do this, we studied the most important variables, both clinical and associated with the electrophysiological study and ablation. Among the clinical variables studied are age, sex, LVEF, NYHA functional class, smoking, systemic arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, obesity, chronic kidney disease, previous AMI, atrial fibrillation, the use of drugs, presentation as electrical storm. Among the variables related to the electrophysiological study are the number of mapping techniques, use during intracardiac echocardiography, presence of clinical VT during ablation, presence of VT other than clinical, and type of anesthesia.

The data was analyzed in the IBM SPSS statistics database software. Baseline characteristics were presented as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation (±SD) for continuous variables. We entered the data of the aforementioned variables in double entry tables (2x2) where the results of patients with recurrence and without recurrence were compared to find the Odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval. For this analysis we only consider the first procedure for each patient, (38 procedures). Data obtained from re-ablations were not included for statistical analysis

Results

From 2015 to 2022, we performed 50 electrophysiological studies and VT ablation in 38 patients with IHD. The mean age was 58.08 ± 9.12 years, and 84.2% were male. Mean left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) was 33.09 ± 12.3%, most patients were in functional class NYHA II and the average QRS length in sinus rhythm was 124.7 ± 34.3 msec. Other clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Basal characteristics of the patients.

| Patients (n=38) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Principal characteristics | ||

| Male sex | 32 | 84.2 |

| Age (y) (mean ± SD) | 58.1 ± 9.1 | |

| LVEF (%)(mean ± SD) | 33.1 ± 12.3 | |

| Electrical storm | 10 | 26.3 |

| ICD before the ablation | 14 | 36.8 |

| Functional class | ||

| NYHA I | 11 | 29.0 |

| NYHA II | 20 | 52.6 |

| NYHA III | 6 | 15.8 |

| NYHA IV | 1 | 2.6 |

| Coronary risk factors | ||

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 17 | 44.7 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 16 | 42.1 |

| Smoking | 14 | 36.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 10 | 26.3 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 | 23.7 |

| Obesity | 7 | 18.4 |

| Cardiovascular history | ||

| Prior AMI | 34 | 88.5 |

| PCI | 22 | 57.9 |

| CABG | 5 | 13.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 | 7.9 |

| Cardiovascular drugs | ||

| Betablockers | 25 | 65.8 |

| ACEI / ARB / ARNI | 23 | 60.5 |

| MRA | 14 | 36.7 |

| ASA | 31 | 81.6 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 21 | 55.3 |

| OAC | 10 | 26.3 |

| Amiodarone | 25 | 65.8 |

AMI=acute myocardial infarction, ACEI= Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB=Angiotensin receptor blocker, ARNI= angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, ASA=acetylsalicylic acid, CBAG=coronary artery bypass grafting ICD=implantable cardioverter defibrillator, LVEF= left ventricle ejection fraction, MRA=Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, PCI= percutaneous coronary intervention, OAC=oral anticoagulant. SD= standard deviation

Three patients had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), five patients had another arrythmia, two of them typical atrial flutter and the others atrial ventricle node reentry tachycardia (AVNRT). Thirty seven percent of patients had an ICD prior to ablation. The median follow-up time was 13 months (IQ range 18.9 moths), during the follow-up 3 patients died.

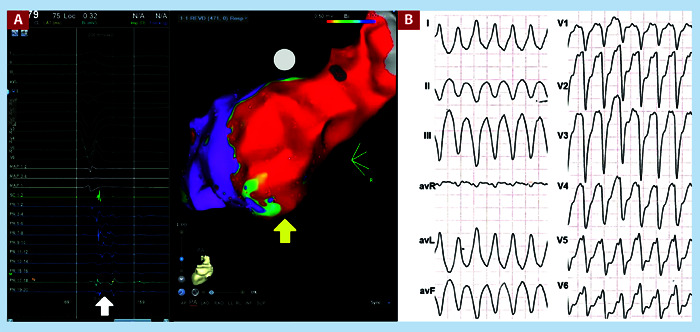

Clinical VT was documented in a 12-lead electrocardiogram in 32 patients (81.5%). The mean cycle length (CL) was 410 ± 85.1 msec. The mean QRS duration was 150.7 ± 34.8 msec. Most patients (57.8%) presented VT with right-bundle branch block morphology (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the electroanatomical reconstruction of the left ventricle with abnormal potentials of a patient with inferior infarction, as well as his clinical VT with left bundle branch block morphology.

Table 2. Ventricular tachycardia characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Cycle length | 410 ± 85.1 ms | 240 - 595 |

| QRS wide | 150.7 ± 34.8 ms | 120 - 220 |

| Morphology | Number | Percentage |

| LBBB morphology | 8 | 21.0% |

| RBBB morphology | 22 | 57.9% |

| V1 Isoelectric | 1 | 2.6% |

LBBB Left bundle branch block. RBBB Right bundle branch block.

Figure 1. A. Voltage map showing a dense scar on the posterior wall of the left ventricle (yellow arrow), fragmented potentials were found in this area (white arrow). Ablation was performed with the substrate modulation technique. This study corresponds to a 49-year-old male patient with dilated ischemic cardiomyopathy. B. Clinical VT of the patient, the QRS is negative in V1 with superior axis, its origin was from the lower basal wall of the left ventricle.

We performed 50 procedures, 28 patients underwent only one ablation procedure, 9 patients underwent two, and one patient underwent up to four ablations. Retro-aortic access was the most used and most procedures were performed under general anesthesia. The characteristics of the procedures are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Characteristics of the procedures.

| Procedures (n=50) | ||

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Principal Characteristics | ||

| Retro aortic access | 44 | 88.0 |

| General anesthesia | 15 | 30.0 |

| Epicardial approach | 3 | 6.0 |

| Clinical VT at the procedure | 33 | 66.0 |

| No clinical VT at the procedure | 13 | 26.0 |

| ICE | 13 | 26.0 |

| Outcomes | ||

| Acute success | 41 | 82.0 |

| Recurrence | 14 | 28.0 |

| Major complications | 9 | 18.0 |

| Electroanatomical mapping | ||

| CARTO® | 45 | 90.0 |

| ENSITE® | 5 | 10.0 |

| Mapping technique | ||

| Mapping by substrate | 43 | 86.0 |

| Activation mapping | 29 | 58.0 |

| Pace mapping | 21 | 42.0 |

| Entrainment | 3 | 6.0 |

| More than one technique | 35 | 70.0 |

| More than two techniques | 9 | 18.0 |

ICE=Intracardiac echocardiography, VT= Ventricular tachycardia.

Considering only the first ablation procedure for each patient, the acute success rate was 82% and the recurrence rate during follow-up was 33%, but the recurrence rate decreased to 28%, including re-ablations. There were nine cases with a major complication: four patients had atrioventricular block during the procedure as a result of the application of radiofrequency in regions with Purkinje potentials, three patients had complications related to vascular access (a significant hematoma, an arterial pseudo aneurysm, and a dissection of the iliac artery), one patient presented a significant pericardial effusion, and the last one died due to incessant VT.

The most frequent mapping technique was substrate-guided mapping (Table 3). We use entrainment only in 3 cases (6%), because most patients did not tolerate tachycardia due to hemodynamic decompensation. Once the myocardial sites involved in the tachycardia circuits were identified, substrate modulation was performed using the scar homogenization technique to eliminate fragmented and late potentials. Likewise, decanalization or linear ablation was performed in cases where the circuit was well defined.

The analysis of factors associated with VT recurrence showed that female sex (OR 3.33, IC 95% 1.66-6.68, p=0.006), atrial fibrillation (OR 3.5, IC 95% 2.08-5.9, p=0.012), NYHA functional class > II (OR 2.4, IC 95% 1.06-5.41, p=0.045) and electrical storm (OR 2.4, IC 95% 1.06-5.41, p=0.045) were the main risk factors for recurrence. (Table 4).

Table 4. Factors associated with ventricular tachycardia recurrence.

| Factor | No recurrence (n=25) | Recurrence (n = 13) | OR | IC 95% | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.2 ± 8.7 | 57.85 ± 10.25 | |||

| Age > 65 | 5 (20.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 1.43 | 0.58 - 3.54 | 0.459 |

| Female | 1 (4.2%) | 5 (44.4%) | 3.33 | 1.66 - 6.68 | 0.006 |

| LVEF | 31.9 ± 12.4 | 33.7 ± 12.5% | |||

| LVEF < 35% | 14 (56.0%) | 8 (61.5%) | 1.16 | 0.47 - 2.89 | 0.743 |

| NYHA | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | |||

| NYHA > II | 2 (8%) | 5 (44.4%) | 2.86 | 1.34 - 6.10 | 0.018 |

| Smoking | 10 (40.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 0.76 | 0.29 - 2.01 | 0.516 |

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 11 (44.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 1.06 | 0.44 - 2.55 | 0.899 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 12 (48.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 0.61 | 0.23 - 1.63 | 0.307 |

| Dyslipidemia | 6 (24.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 1.24 | 0.49 - 3.14 | 0.653 |

| Obesity | 5 (20.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.81 | 0.23 - 2.83 | 0.728 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 5 (20.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 1.43 | 0.58 - 3.54 | 0.459 |

| Previous AMI | 22 (88.0%) | 12 (92.3%) | 1.41 | 0.25 - 8.12 | 0.681 |

| AF | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (23.7%) | 3.5 | 2.08 - 5.9 | 0.012 |

| Betablockers | 19 (76.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 0.45 | 0.19 - 1.05 | 0.066 |

| ACEI / ARB / ARNI | 14 (56.0%) | 9 (69.23%) | 1.47 | 0.55 - 3.90 | 0.429 |

| MRA | 9 (26.0%) | 5 (44.4%) | 1.0 | 0.44 - 2.63 | 0.881 |

| Amiodarone | 16 (64.0%) | 9 (69.23%) | 1.17 | 0.45 - 3.07 | 0.747 |

| Electrical storm | 4 (16.0%) | 6 (46.2%) | 2.4 | 1.06 - 5.41 | 0.045 |

| >1 technique for mapping | 18 (72.0%) | 7 (53.8%) | 0.61 | 0.26 - 1.43 | 0.263 |

| >2 technique for mapping | 9 (36.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.64 | 0.48 - 0.86 | 0.013 |

| ICE | 5 (20.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0.56 | 0.09 - 3.66 | 0.519 |

| Clinical VT at the procedure | 21 (84.0%) | 5 (44.4%) | 0.29 | 0.12 - 0.70 | 0.004 |

| No clinical VT | 6 (24.0%) | 4 (30.7%) | 1.24 | 0.49 - 3.14 | 0.456 |

| General Anesthesia | 7 (28.0%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0.31 | 0.05 - 2.04 | 0.145 |

LVEF= left ventricle ejection fraction, AMI = Acute myocardial infarction, AF= Atrial fibrillation , ACEI= Angiotensin-ACEI: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB=Angiotensin receptor blocker, ARNI= angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor, MRA=Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, ICE=Intracardiac echocardiography, VT= Ventricular tachycardia.

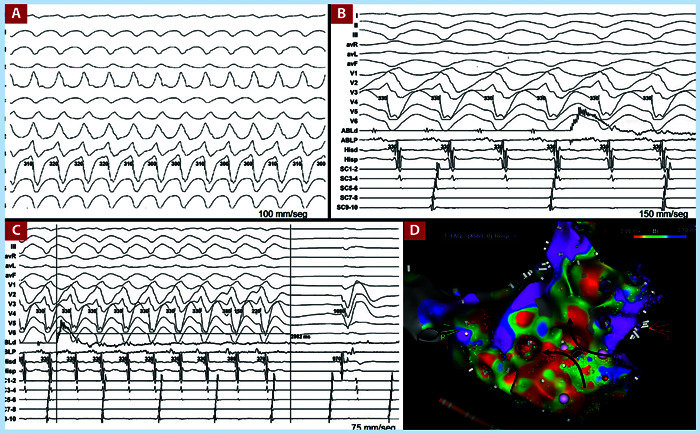

On the other hand, within the variables related to ablation, the presence of the clinical VT at the time of the procedure either spontaneously or induced was associated with less recurrence (OR 0.29, IC 95% 0.12-0.70, p=0.004). Figure 2 highlights the importance of mapping during tachycardia. This figure shows an electroanatomical reconstruction of the left ventricle performed during tachyardia, where it was possible to identify its critical isthmus, which allowed us to stop it with a single application of radiofrequency. Consequently, the fact of being able to use multiple techniques in the presence of clinical VT reduced the recurrence rate, the use of more than two mapping techniques was also a protective factor (OR 0.64, IC 95% 0.48-0.86, p=0.013) (Table 4).

Figure 2. A. Clinical VT of a 62-year-old male with arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus and multiarterial coronary artery disease. B. Pre-ablation position, the ablation catheter is positioned at the critical point of the tachycardia, where diastolic potentials are observed. The artifact of radiofrequency starts is also observed. C. TV stop after 2.9 seconds of RF start. D. Voltage map on an unconventional scale, where the critical isthmus of TV is identified, right in the middle of the isthmus is the ablation point that managed to end TV.

Discussion

Our series is the largest TV ablation series in IC in Mexico. with a high acute success rate, greater than 80%, and an acceptable recurrence rate of 28%, like that reported by other authors in industrialized countries. Likewise, we found that there are some risk factors associated with VT recurrence and also the existence of protective factors such as the presence of clinical VT during ablation and the use of more than two mapping techniques. These findings highlight the importance of induction of VT during the electrophysiological study in case it is not present spontaneously and the importance of mapping during clinical VT.

Our findings have some similarities and some differences compared to those published by other authors. For example, Di Biase et al. and Nakara et al. in their respective series of patients with IHD and VT, found that, most patients were male, but the LVEF was lower compared to our population 12,13. Also, the percentage of systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus was lower in our study compared to others from USA and Europe 12-16.

An important aspect is that not all the patients in our study have a history of previous AMI, since some patients had only chronic stable angina and even in a minority, VT was the first manifestation of IHD. This is an important difference compared to studies conducted in industrialized countries where all patients with IHD and VT have a history of AMI.

Ischemic cardiomyopathy scars have a sub-endocardial distribution but can also have a transmural extension, which can make ablation challenging 2,8. The endocardial-epicardial approach in patients with IHD generates better results in the follow-up since it reduces recurrence 12,17. Because the epicardial approach is not free of complications, we use this approach only in cases when the electrocardiogram suggested an epicardial origin, in our series, the epicardial approach was necessary in three patients with no recurrences.

It is necessary to use an electroanatomic mapping system in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy, which will allow us to define the areas of dense scar, normal myocardium, and borderline tissue 8,9. On the other hand, there are multiple types of strategies that can be used for mapping, one of the techniques that has proven to be very useful is mapping guided by substrate, which consists of identify areas with local abnormal ventricular activities (LAVA) and apply radiofrequency in these areas until the disappearance or dissociation of these potentials 14-17. This technique was the most used in our study and in all cases, we performed substrate modulation.

The success rate, and major complications in our study were similar to that reported by Vergara et al. 18. Previously, Wolf et al. 15 reported in a series of 57 patients with IHD and VT who were taken to ablation that the incidence of clinical VT during the procedure was 73% 15, while in our study was 66%, on the other hand, it should be noted that a significant percentage of patients presented a VT different from the clinical one (26%). This is an important finding since the presence of non-clinical ventricular tachycardias is associated with a poor prognosis in these patients and even with recurrence of clinical VT 15.

Despite advances in VT ablation, recurrence remains one of the major challenges. It remains unknown whether VT recurrence reflects disease progression or failure of the procedure, several reports found than an adverse prognosis depends on clinical variables, such as the inability to eliminate all VTs during the ablation procedure, advanced age, NYHA class and the presence of AF. Also, there is evidence that early recurrences are associated with high risk of adverse prognosis, and the risk decreases gradually with later recurrences 19.

We found that female sex was a significant risk factor for VT recurrence, however in the VISTA Randomized Multicenter Trial no statistically significant differences were found between both sexs 14. The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias is usually lower in women than in men with ischemic heart disease, but women experience greater adverse effects with optimal medical therapy, which can lead to its abandonment, and this could be associated with an increase in recurrence of the VT, however this is only a hypothesis since women are underrepresented in most clinical trials 20,21. It has also been reported that diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for recurrence, however despite that in our population the prevalence of diabetes was higher compared to other studies, it did not influence recurrence 14,19. Unlike other studies, we did not find differences in terms of age.

One of the very common comorbidities in patients with IHD is AF, which reflex atrial fibrosis. In the context of IHD, AF can reflex more advanced disease and could be associated with greater recurrence, it is also known that the association of these two pathologies worsens the prognosis of patients. Like Siontis et al., we found that AF increase the recurrence rate 19.

Another factor that had a significant impact on recurrence was the presence of clinical VT during the procedure. This suggests that, although hemodynamically poorly tolerated in many cases, it is always important to try to induce clinical VT to improve success and reduce recurrence. Previously, it had been reported that the presence of clinical VT at the time of ablation could be associated with less recurrence 19. Likewise, the presence of clinical VT allows the use of more mapping techniques, such as entrainment or activation mapping 1,2. In this series, there were 9 patients in which we used more than two mapping techniques, none of whom presented recurrence.

Haanschoten et al. (22 also reported that failure of antiarrhythmic drugs, total revascularization, ablation type and electrical storm before ablation were important factors of recurrence. In our series we find an association between the electrical storm and recurrence but not with the revascularization and the ablation type, which may be due to the size of the sample and differences between populations. Another important factor for recurrence and mortality is the low LVEF, which is part of the novel predictive score for survival and recurrence proposed by Vergara et al in 2018, despite that, we did not find a statistically significant association between the LVEF and recurrence 23, but if we find a relationship between the functional class and the recurrence, the NYHA functional class greater than 2 was associated with greater recurrence, this finding is consistent with that previously reported by other authors 19.

Finally, in patients with previous AMI, is very important to assess transmural scar with imaging studies (resonance or nuclear medicine) since in the group of patients with transmural infarction, the epicardial approach has been associated with less recurrence 24. Unfortunately, in our series few patients underwent epicardial ablation.

This study has several limitations: the inherent limitations of a retrospective analysis, the fact that was a single-center observational study which included a small sample of patients, that limits the statistical power to detect independent predictors of mortality and recurrence. Another important limitation is the low rate of epicardial approaches performed. Is important to consider the development of the operators’ skills, since their experience has increased over the years.

In conclusion VT catheter ablation in IHD has a good effectiveness and a relatively low recurrence rate despite some major complications. In Mexican population, female sex, atrial fibrillation, electrical storm, NYHA functional class greater than 2 increase the rate of recurrence, while the presence of the clinical VT during the ablation and the use of more than 2 techniques for mapping procedure are protective factors.

Footnotes

Financing: This research has not received any specific grant from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors

Cueva-Parra A, Neach-De La Vega D, Yañez-Guerrero P, Bustillos-García G, Gómez-Flores J, Levinstein M, et al. Acute and long-term success of ventricular tachycardia ablation in patients with ischemic heart disease in a Mexican center. Arch Peru Cardiol Cir Cardiovasc. 2022;3(4). doi: 10.47487/apcyccv.v3i4.236

References

- 1.Dukkipati SR, Koruth JS, Choudry S, Miller MA, Whang W, Reddy VY. Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Tachycardia in Structural Heart Disease Indications, Strategies, and Outcomes-Part II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(23):2924–2941. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cronin EM, Bogun FM, Maury P, Peichl P, Chen M, Namboodiri N, et al. 2019 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Europace. 2019;21(8):1143–1144. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(25):1882–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy VY, Reynolds MR, Neuzil P, Richardson AW, Taborsky M, Jongnarangsin K, et al. Prophylactic catheter ablation for the prevention of defibrillator therapy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(26):2657–2665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuck KH, Schaumann A, Eckardt L, Willems S, Ventura R, Delacrétaz E, et al. Catheter ablation of stable ventricular tachycardia before defibrillator implantation in patients with coronary heart disease (VTACH) a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9708):31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sapp JL, Wells GA, Parkash R, Stevenson WG, Blier L, Sarrazin JF, et al. Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation versus Escalation of Antiarrhythmic Drugs. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuck KH, Tilz RR, Deneke T, Hoffmann BA, Ventura R, Hansen PS, et al. Impact of Substrate Modification by Catheter Ablation on Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Interventions in Patients With Unstable Ventricular Arrhythmias and Coronary Artery Disease Results From the Multicenter Randomized Controlled SMS (Substrate Modification Study) Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2017;10(3):e004422. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, Bryant WJ, Callans DJ, Curtis AB, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death Executive summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15(10):e190–e252. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vergara P, Roque C, Oloriz T, Mazzone P, Della Bella P. Substrate mapping strategies for successful ablation of ventricular tachycardia a review. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2013;83(2):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.acmx.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim YH, Chen SA, Ernst S, Guzman CE, Han S, Kalarus Z, et al. 2019 APHRS expert consensus statement on three-dimensional mapping systems for tachycardia developed in collaboration with HRS, EHRA, and LAHRS. J Arrhythm. 2020;36(2):215–270. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosa E, Scanavacca M, d'Avila A, Pilleggi F. A new technique to perform epicardial mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7(6):531–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Burkhardt DJ, Bai R, Mohanty P, Carbucicchio C, et al. Endo-epicardial homogenization of the scar versus limited substrate ablation for the treatment of electrical storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(2):132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakahara S, Tung R, Ramirez RJ, Michowitz Y, Vaseghi M, Buch E, et al. Characterization of the arrhythmogenic substrate in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy implications for catheter ablation of hemodynamically unstable ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(21):2355–2365. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Lakkireddy D, Carbucicchio C, Mohanty S, Mohanty P, et al. Ablation of Stable VTs Versus Substrate Ablation in Ischemic Cardiomyopathy The VISTA Randomized Multicenter Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(25):2872–2882. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf M, Sacher F, Cochet H, Kitamura T, Takigawa M, Yamashita S, et al. Long-Term Outcome of Substrate Modification in Ablation of Post-Myocardial Infarction Ventricular Tachycardia. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(2):e005635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briceño DF, Romero J, Villablanca PA, Londoño A, Diaz JC, Maraj I, et al. Long-term outcomes of different ablation strategies for ventricular tachycardia in patients with structural heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2018;20(1):104–115. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tung R, Michowitz Y, Yu R, Mathuria N, Vaseghi M, Buch E, et al. Epicardial ablation of ventricular tachycardia an institutional experience of safety and efficacy. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(4):490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vergara P, Trevisi N, Ricco A, Petracca F, Baratto F, Cireddu M, et al. Late potentials abolition as an additional technique for reduction of arrhythmia recurrence in scar related ventricular tachycardia ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23(6):621–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2011.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siontis KC, Kim HM, Stevenson WG, Fujii A, Bella PD, Vergara P, et al. Prognostic Impact of the Timing of Recurrence of Infarct-Related Ventricular Tachycardia After Catheter Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2016;9(12):e004432. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.116.004432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lam CSP, Arnott C, Beale AL, Chandramouli C, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaye DM, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(47):3859–3868c. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehdaie A, Cingolani E, Shehata M, Wang X, Curtis AB, Chugh SS. Sex Differences in Cardiac Arrhythmias Clinical and Research Implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(3):e005680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.117.005680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haanschoten DM, Smit JJJ, Adiyaman A, Ramdat Misier AR, Hm Delnoy PP, Elvan A. Long-term outcome of catheter ablation in post-infarction recurrent ventricular tachycardia. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2019;53(2):62–70. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2019.1601253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vergara P, Tzou WS, Tung R, Brombin C, Nonis A, Vaseghi M, et al. Predictive Score for Identifying Survival and Recurrence Risk Profiles in Patients Undergoing Ventricular Tachycardia Ablation The I-VT Score. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2018;11(12):e006730. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.118.006730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acosta J, Fernández-Armenta J, Penela D, Andreu D, Borras R, Vassanelli F, et al. Infarct transmurality as a criterion for first-line endo-epicardial substrate-guided ventricular tachycardia ablation in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13(1):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]