Abstract

This study used focus group methodology to identify culturally-specific barriers to, and facilitators of, eating disorder (ED) treatment-seeking for South Asian (SA) American women. Seven focus groups were conducted with 54 participants (Mage=20.11 years, SD=2.52), all of whom had lived in the United States (US) for at least three years (63.0% of the sample was born in the US). Transcripts were independently coded by a team of researchers (n=4) and the final codebook included codes present in at least half of the transcripts. Thematic analysis identified salient themes (barriers, n=6; facilitators, n=3) for SA American women. Barriers to ED-treatment seeking were inextricable from barriers to mental health treatment, more broadly. In addition to generalized mental health stigma, participants cited social stigma (i.e., a pervasive fear of social ostracization), as a significant treatment-seeking barrier. Additional barriers were: cultural influences on the etiology and treatment of mental illness, parents’ unresolved mental health concerns (usually tied to immigration), healthcare providers’ biases, general lack of knowledge about EDs, and minimal SA representation within ED research/clinical care. To address these obstacles, participants recommended that clinicians facilitate intergenerational conversations about mental health and EDs, partner with SA communities to create targeted ED psychoeducational health campaigns, and train providers in culturally-sensitive practices for detecting and treating EDs. SA American women face multiple family, community, and institutional barriers to accessing mental health treatment generally, which limits their ability to access ED-specific care. Recommendations to improve ED treatment access include: (a) campaigns to destigmatize mental health more systematically, (b) collaboration with SA communities and, (c) and training providers in culturally-sensitive care.

Keywords: South Asians, eating disorders, treatment barriers, treatment facilitators, Asian Americans

Eating disorders (EDs) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Arcelus et al., 2011; Treasure et al., 2020). Although EDs were initially thought to only affect individuals in Westernized, industrialized countries (e.g., typically White women; Prince, 1985), it is now clear that these conditions can affect individuals of all races/ethnicities, countries of origin, religions, and genders (Cheng et al., 2019; Schaumberg et al., 2017). Despite this, women of color are less likely to be screened, referred, and treated for EDs (Alegria et al., 2002; Becker et al., 2003; Marques et al., 2011). Specifically, South Asians (SAs) – individuals descended from India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and/or the Maldives – are the second fastest growing ethnic group in the United States (US; Hoeffel et al., 2010); yet, they are vastly underrepresented in the ED literature, perpetuating these health disparities (Inman et al., 2014; Iyer & Haslam, 2003, 2006).

General Barriers to Mental Healthcare Utilization

It is difficult to identify the exact prevalence of specific mental health conditions among SAs living in the US, given the lack of population-based epidemiological studies including SAs (Tummala-Narra & Deshpande, 2018). Given this caveat, current prevalence estimates for mental health concerns, such as 12-month DSM-IV mood and anxiety disorders, are 1.2% and 3.3%, respectively (Masood et al., 2009). These estimates are substantially lower than those reported in the general US population, in which 8.9% and 18.1% of adults endorsed experiencing any mood or anxiety disorder within the last year, respectively (Kessler et al., 2005). However, it is likely that these rates for SAs are underestimates, due to multiple treatment barriers, including difficulties accessing care, differing cultural understandings of mental illness, and pervasive mental health stigma (Arora et al., 2016; Sue et al., 2012).

Specifically, there are numerous difficulties regarding mental health access and provision that contribute to treatment disparities for SAs. In both the US and abroad, Asians, including SAs, exhibit low rates of mental healthcare utilization (Fountain & Hicks, 2010; Leung et al., 2011; Sue et al., 2012), mainly due to widespread mental health stigmatization (Arora et al., 2016; Kermode et al., 2009; Loya et al., 2010; Rastogi et al., 2014; Shidhaye & Kermode, 2013). However, when SAs do present for mental health treatment, they often first seek services from a primary care provider (PCP), who might not be well-trained in the detection and diagnosis of psychiatric conditions (Leung et al., 2011). Additionally, there is usually a significant delay in treatment-seeking until symptoms manifest physically and/or are severe (Loya et al., 2010; Shidhaye & Kermode, 2013).

Barriers to psychological help-seeking for SAs in the US are evident both within SA groups, and from others. Specifically, providers from other racial and ethnic groups might inadvertently limit SAs’ access to mental health treatment as a result of racial discrimination, and lack of knowledge about immigration and cultural experiences (Inman et al., 2014; Karasz et al., 2019). Furthermore, treatment services may not be available in languages spoken by SAs, limiting the accessibility of services for those with low English proficiency, or other communication difficulties (Quay et al., 2017). These disparities are compounded by low representation of SA providers within the mental health field, potentially limiting the visibility, recognition, and understanding of these health conditions amongst both providers and patients (Inman et al., 2014).

In addition, pervasive mental illness stigma likely accounts for, or exacerbates, many of the aforementioned treatment barriers, preventing a majority of SAs from seeking care (Arora et al., 2016; Kermode et al., 2009; Loya et al., 2010; Rastogi et al., 2014; Shidhaye & Kermode, 2013). In particular, Chaudhry and Chen (2019) note that SAs are vulnerable to a specific form of mental illness stigma known as courtesy stigma. This term refers to a social contagion effect, by which both the individual with a mental illness, and their family members, are stigmatized and considered “socially contaminated” (Chaudhry & Chen, 2019, p. 155; Corrigan & Miller, 2004; Moses, 2014; Rao & Valencia-Garcia, 2014). Thus, SAs might avoid treatment-seeking in order to prevent any collateral community stigma towards their family members. Preliminary data suggest that courtesy stigma is a more salient and unique barrier to help-seeking for SAs, relative to their White peers (Chaudhry & Chen, 2019). Thus, mental health stigma might be nuanced in how it presents in SA communities, although additional research is needed to clarify this issue.

A final barrier to help-seeking includes internalization of the model minority stereotype, which postulates that Asians, including SAs, are inherently endowed with qualities that make them more likely to succeed, relative to other racial minorities, such as a strong dedication to and emphasis on education, a strong work ethic, and obedience (Gupta et al., 2011). This stereotype is often associated with high academic achievement and socioeconomic status. Within this context, seeking mental health care might be viewed as an admission of failure, implying that an individual is not embodying the expectations associated with this “positive” stereotype (Yip et al., 2021). For all of these reasons, SAs might be less likely to self-identify mental health symptoms and seek appropriate treatment.

Specific Barriers to ED Treatment-Seeking

Although researchers previously believed that SAs were less vulnerable to ED pathology due to differing shape/weight ideals (Khandelwal & Saxena, 1990; Littlewood, 1995), investigations conducted outside of the US have demonstrated that EDs affect SAs at rates similar to those observed in other racial/ethnic groups (i.e., 0.2-2% for SAs vs. 0.3-1.2% for Western White populations; Hudson et al., 2007; Levinson & Brosof, 2016), and are accompanied by the same psychological and medical complications observed in samples of White women (Mehler & Andersen, 2017; Treasure et al., 2020; Vaidyanathan et al., 2019). Nonetheless, SAs are less likely to be assessed, referred, and treated for an ED relative to their White peers (Abbas et al., 2010).

Preliminary research attempting to identify disruptions in the treatment access-referral pathway have identified several key barriers to ED treatment-seeking for SAs. Notably, many Asian patients with EDs, including SAs, view this disorder as a physical, rather than psychological, illness, and initially seek services from PCPs (Anand & Cochrane, 2005; Ting & Hwang, 2007). However, PCPs are often not trained to detect “atypical” EDs (e.g., presentations that differ from standardized Western nosology, Abbas et al., 2010; Striegel-Moore et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2000). Moreover, although paradigms are slowly shifting, many patients and providers are still susceptible to the myth that EDs only affect White, Western, middle-class women, further hindering treatment access and detection (Gordon et al., 2006; Nelson et al., 2011). Thus, in addition to culturally-specific barriers to treatment, racial biases that perpetuate ED diagnosis and treatment disparities among other underrepresented racial and ethnic groups appear to apply to SA women as well (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006; Becker et al., 2010).

Similar to other mental illnesses, EDs are also highly stigmatized and poorly understood among SAs. For example, barriers to treatment-seeking identified in a qualitative study conducted with a non-clinical sample of SAs in the United Kingdom (UK) included: a lack of knowledge about EDs, stigmatization of EDs in the SA community, and concerns about confidentiality when seeking care (Wales et al., 2017). These findings are similar to those of another qualitative study in the UK, in which treatment-seeking SA women with EDs noted that their parents initially did not acknowledge their condition, and only felt comfortable seeking services when it became clear their physical health was compromised (Hoque, 2011). As a result of this delay, their symptoms were much more severe than those of White women at treatment initiation (Hoque, 2011). Interpreted collectively, these findings provide further evidence that EDs are highly stigmatized within this community, contributing to treatment delays and elevated ED symptom severity.

Study Aims

To date, only three-peer reviewed investigations have examined EDs among SAs in the US (i.e., Chang et al., 2014; Iyer & Haslam, 2003; Reddy & Crowther, 2007). Even less research has examined culturally-specific barriers to and facilitators of ED treatment-seeking among SA Americans. Although others have attempted to examine barriers to care outside of the US (e.g., Hoque, 2011; Wales et al., 2017), many of the seminal articles that inform our knowledge about EDs amongst SAs date back to the 1990s (e.g., Mumford et al., 1991, 1992). Furthermore, SA Americans might experience unique treatment barriers related to both the US healthcare system, and their positioning within America as racial minorities (Bhatia & Ram, 2018; Inman et al., 2014; Prashad, 2000). As such, this study used focus group methodology to investigate SA American women’s perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of ED treatment-seeking in the US. Given this study’s exploratory nature, no a priori hypotheses were established; instead, interpretations were inductive and data-driven (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Elo & Kyngas, 2008).

Methods

Participants

Data were derived from a larger qualitative investigation assessing SA American women’s conceptualizations of body image and EDs (see Goel et al., 2021 for more details on study design and procedures). Briefly, participants were SA American females recruited from a public southeastern university. Eligible individuals were: female, age ≥18 years, nulliparous, of SA descent (i.e., at least one parent or grandparent was born in SA), and living in the US for ≥ three years. Further, participants did not need to have any lived experience or knowledge of EDs in order to participate; our goal was to survey a representative sample of the broader female SA American population living in the area. Participants were recruited through a variety of methods, including email listservs to culturally-relevant student groups, the psychology department research pool, and snowballing techniques. Informed consent was obtained in-person prior to participation. All study procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Procedure

A qualitative study design was chosen because, compared with a quantitative approach, it allows researchers to gain insight and elicit exploration within an under-researched community and/or area of interest (Creswell & Poth, 2018). All study procedures, including recruitment, data collection, and interpretation were vetted by seasoned qualitative health researchers who have experience working with marginalized communities. Data were collected during fall 2018. Recruitment materials directed interested individuals to contact the lead investigator. Participants received $15, and (if applicable) 1.5 research credits for their time. Seven focus groups were conducted, each with 6-10 participants (total N=54). Each focus group was moderated by the first author, spanned approximately 90 minutes, and audio recorded. Participants were instructed to refrain from stating any identifying information to protect confidentiality. They were asked to respond to questions based either on their personal experience, or that of friends and family members. Each group followed the same protocol, using a semi-structured interview guide developed for this study (see Appendix A). Of note, this guide was created in collaboration with qualitative health researchers, and vetted by two SA-identified professors at the authors’ university. The moderator employed a “funnel approach” with her directed questioning, such that she began the meeting with broader, more-open ended questions, then invited discussion on a few key central topics, and closed with more directed, specific questions on a particular area (Morgan, 1998). As such, the moderator followed a trajectory that began with a broad overview and ended with a narrowed focus. A process observer who identified as a SA woman observed most focus groups (5/7; two were missed due to a scheduling conflict) and took relevant notes.

As recommended (Krueger, 1988), focus groups were conducted until saturation was achieved (i.e., the point at which no new relevant information was introduced by groups). This was determined by the principal investigator (first author) and the process observer, who met after each focus group and observed substantial repetition of key ideas by the completion of the seventh group. After each group, participants completed a brief self-report questionnaire assessing demographic characteristics.

Research Team

The data collection team included the first author, who facilitated the groups, and the process observer. Coders were three graduate research assistants (RAs, including the first author), an undergraduate RA who volunteered to serve on the coding team after participating in the study, and one faculty member. Prior to data analysis, coders were trained by the principal investigator in best practices in qualitative research (e.g., documenting notes and ideas during analytic process), as well as methods specific to the current investigation (e.g., remaining data-near according to qualitative descriptive approach and thematic analysis). Coders reviewed de-identified transcripts.

To enhance data trustworthiness and rigor, researchers are encouraged to practice reflexivity by stating their backgrounds and potential biases prior to data analysis (Creswell & Poth, 2018). The first author is a SA (Indian) American female in her mid-20s. The second author is a White American female graduate student in her mid-20s. The third is a Black female doctoral student in her early 30s. The undergraduate RA is a SA woman in her early 20s. The last team member is a White professor in her mid-40s.

Analytic Strategy

Audio files were transcribed verbatim by RAs. Transcripts were reviewed by the first author to check accuracy and address any contextual issues (e.g., provide explanations for culturally-specific, non-English words/concepts).

Researchers employed a qualitative descriptive approach for the current study design. Qualitative descriptive approaches describe individuals’ experience with a particular phenomenon using their own words, while providing researchers the methodological and theoretical flexibility to identify important themes and concepts (Sandelowski, 2000; Willis et al., 2016). Thematic analysis is an analytic method that is particularly compatible with qualitative descriptive approaches. This recursive method requires repeatedly reviewing data and moving fluidly through the stages of analysis to identify the central ideas (“themes”) for each group (Braun & Clarke, 2006). A major strength of thematic analysis is its flexibility (Braun & Clarke, 2006). As is the case with qualitative descriptive approaches (Sandelowski 2000), researchers are not bound to any epistemological, theoretical, or rigidly structured way of conducting their thematic analysis; instead, it can be adapted to match the needs of the research, and importantly, the actual content of the data. Lastly, we employed an inductive approach that allows for the interpretation of themes from a bottom-up perspective, such that all interpretations are data-driven rather than pre-determined.

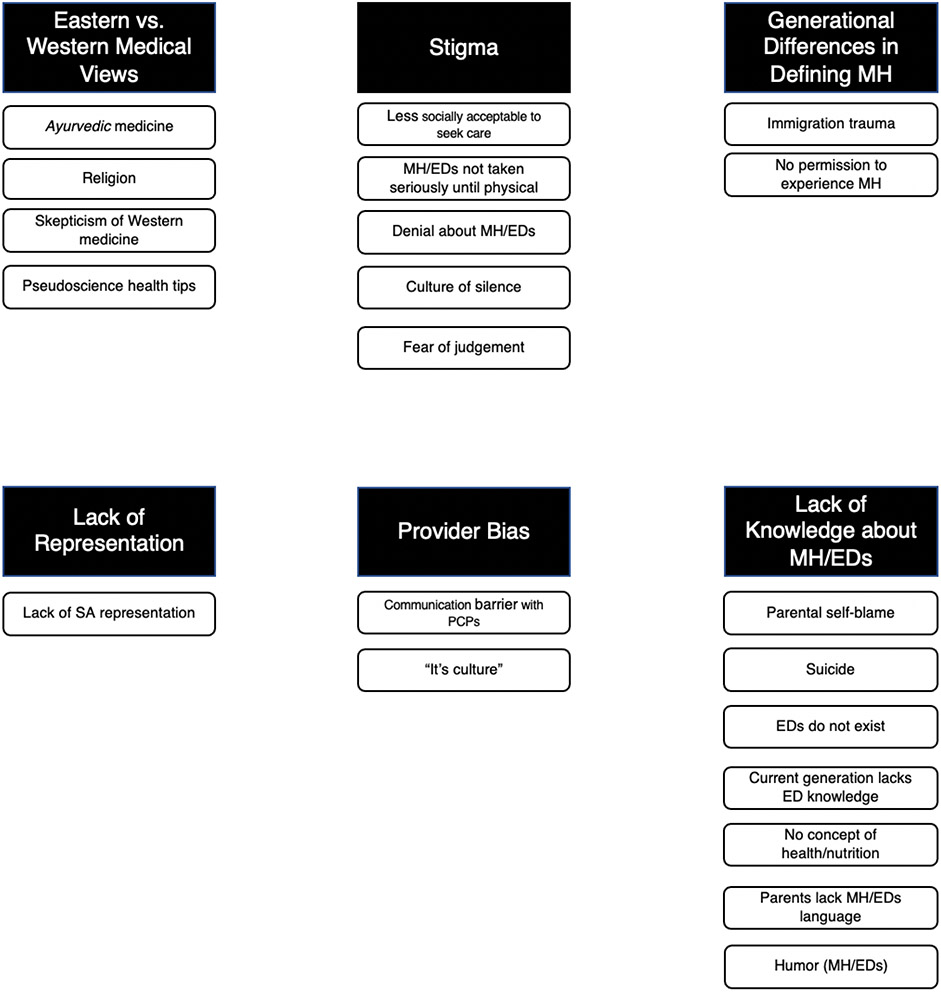

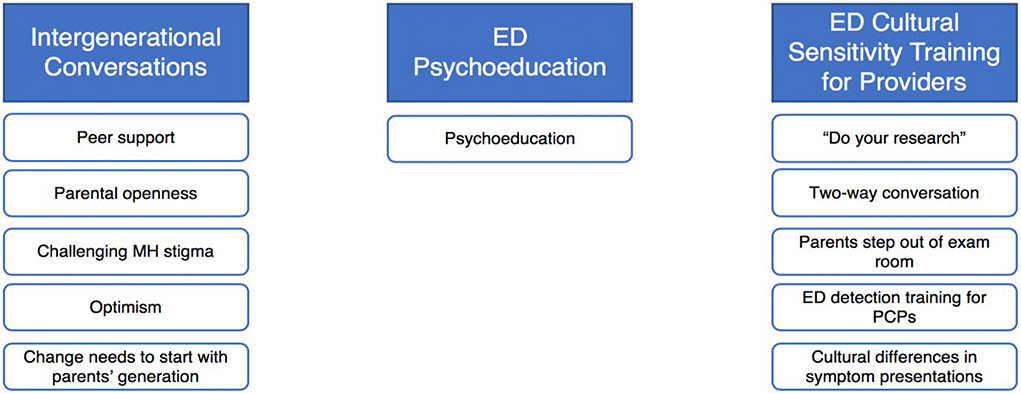

Following the recommendations of Braun and Clarke (2006), coders cycled through the six stages of thematic analysis. The first three stages involved transcription and generating individual codes by organizing the data in meaningful ways. Codes were compiled into thematic maps displaying the overall patterns and their relations (Braun & Clarke, 2006; see Figures 1 and 2). The last three stages focus on transitioning from a specific, lengthy code list to a smaller, more fine-tuned list of broader themes. Though Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method does not require multiple coders, to enhance trustworthiness of results, researchers are encouraged to use multiple validity checks, including some form of peer review in addition to comprehensive documentation (e.g., audit trail; Creswell & Poth, 2018).

Figure 1.

Thematic map for barriers to seeking treatment for a mental health concern and/or an eating disorder, displaying six major themes and their associated codes.

Note. EDs = eating disorders; MH = mental health; SA = South Asian; PCPs = primary care providers.

Figure 2.

Thematic map for facilitators of mental health and/or eating disorders treatment, displaying three major themes and their associated codes.

Note. EDs = eating disorders; MH = mental health; PCPs = primary care providers.

The coding team (n=4) independently coded each transcript according to the research question and met twice to compare and discuss their results; the faculty member oversaw the data collection and analysis process and helped resolve discrepancies. The final codebook only included codes appearing in at least four of the seven transcripts. Researchers offered participants an optional meeting to review findings and vet interpretations, however none attended. We hypothesize the reason for this lack of attendance was because this meeting occurred at the end of academic year, and no additional monetary incentive was provided for meeting attendance. All notes generated from the transcription and data analysis process were included in the audit trail.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants’ average age was 20.11 years (SD=2.52; range 18-30). They were primarily undergraduates (90.7%). Most were recruited through email (22.2%), the psychology research pool (16.7%), student organizations (14.8%), and peers (14.8%). Most were born in the US (63.0%) or in SA (25.9%); a minority were born in a country outside of the US or SA (11.1%). Those not born in the US had lived in this country an average of 14.05 years (SD=5.48). Participants’ mothers and fathers primarily descended from India (59.3% mothers, 61.1% fathers), Bangladesh (18.5% for both), Pakistan (18.5% mothers, 16.7% fathers), Nepal (1.9% for both) and Sri Lanka (1.9% for both). No participants descended from Bhutan or the Maldives. Participants’ parents’ highest level of education was as follows: elementary school (0% mothers, 1.9% fathers), high school (18.5% mothers, 14.8% fathers), bachelors (53.7% mothers, 25.9% fathers) masters (20.4% mothers, 46.3% fathers), doctorate (3.7% mothers, 5.6% fathers), medical degree (MD; 1.9% mothers, 3.7% fathers) and other (1.9% for both). In terms of religious affiliation, participants identified as Hindu (37.0%), Muslim (27.8%), Sikh (9.3%), Christian (1.9%), Buddhist (1.9%), none/not religious (14.8%), and Atheist (1.9%). Participants’ body mass indices (BMIs) (kg/m2) were classified as: underweight (7.4%), normal weight (59.3%), overweight (14.8%), and obese (16.7%). The average BMI for the sample was 24.01 kg/m2 (SD=5.20).

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment (Generally) and ED Treatment (Specifically)

Participants identified six major barriers to mental health and ED treatment-seeking, including: Eastern versus Western medical views, stigma, generational differences in conceptualizations of mental health, lack of knowledge about mental health and EDs, lack of representation, and provider bias (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Of note, many of the participants’ responses (and the resulting themes) focused on barriers to mental health treatment-seeking generally, rather than those specific to EDs. Thus, the first four themes apply more broadly to mental health concerns, while the latter two include specific perceptions of barriers to ED treatment-seeking. Each theme is described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

Table 1.

Barriers to mental health and eating disorders treatment-seeking (N=6).

| Theme | Code | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern versus Western Medical views | Religion | Prayer as a MH intervention, prayer/religion as an explanation for MH | “…And sometimes like, a lot of Pakistani people I’ve noticed, the older ones, they tend to say like, “oh she’s possessed or something…especially if it’s a girl. Like if she’s, if she has a dominant personality or if she’s someone who is like going out and getting what she wants, it’s like, “oh she’s either possessed or something’s wrong with her,” Like that’s a major thing that is pretty common…” (Transcript 3) |

| Skepticism of Western medicine | South Asian parents and older generations appear to distrust Western medication for a variety of reasons, including fears of addiction, side-effects, and long-term effects. | “…And my mom she’s really into herbal things, like ‘I take this,’ or something. But a lot of times that’s not the only way to cure certain things, so I think they’re just scared of - Like my mom says, ‘I don’t want you to be on certain things at such a young age. Like you’re so young right now, you have so much to live for. So, if you start taking medications right now, then when you’re old, what’s going to happen to your body?’” (Transcript 4) | |

| Pseudoscience health tips | Parents and elders give their children pseudoscience tips to cure their MH symptoms. These tips usually lack any empirical basis. Often, these tips are transmitted through social media tools, such as chain messages on WhatsApp. | “…they [older generations] don’t talk about mental health especially eating disorders - it’s seen as like - it’s just not a common topic. And nowadays it is because of all that WhatsApp like chain messages that they send around and they’re like it’s all mistaken information.” (Transcript 3) | |

| Ayurvedic medicine | Older generations may value homemade, Eastern forms of medicine over Western forms of medicine. | “And it’s also the fact that, especially on the Eastern side, that more natural medicine is used. It’s more ayurvedic, like that we made our own concoctions, and like that’s what we know – or we think we know what’s good for our body – and then like we come here [the US] and it’s all like pills and over-the-counter medicine. Yeah we’re skeptical of that.” (Transcript 1) | |

| Stigma | Fear of judgement | Older generations are fearful that if other community members found out that they were experiencing anything resembling MH issues, that they would be shamed and judged for this. As a result, they would experience social embarrassment. | “…and then socially like, ‘oh like what are people going to say? Log kya kahenge? [What will people say?]”(Transcript 3) |

| Less socially acceptable to seek care | Relative to other cultural groups, especially White women, participantsreported that it is socially unacceptable for South Asians to seek therapy or other forms of MH care. | “…like socially, I think it’s [eating disorders treatment] more acceptable with White people ‘cuz they can go to get help with it and stuff. Like beingIndian, South Asian, usually it’s not taken as a big deal – like you wouldn’t go to a therapist or anything to get help. But, like in American culture, it’s more accepted that, ‘oh, this is an eating disorder and this [White] person can go to therapy and, or go get help…” (Transcript 1) | |

| Culture of silence | MH is not discussed. As a result, participants rarely felt comfortable confiding in their parents about their MH concerns, and thus, felt under-supported and alone. | “Yeah I think it’s like there’s no knowledge of it [mental health] because there’s still a stigma. That’s the reason behind it. Because if there weren’t stigma…like it wouldn’t be like ‘hush hush,’ bad to talk about things like this.” (Transcript 3) | |

| Denial about MH/EDs | Parents and older generations deny the existence of MH, including EDs. Individuals presenting with mental illness are often perceived as “crazy” or “contagious.” | “…I was anorexic in uh seventh grade and my mom was just like, ‘oh no, you’re fine.’ Like they didn’t want to talk about - like the doctors would be like, ‘hey, you know, she’s anorexic,’ but it would just be like ‘oh she’s bulimic,’ but they just didn’t want to talk about it. They would just be like, ‘oh, okay, well we’ll watch over her,’ but it’s like, you know, like they didn’t want to specifically diagnose me like that ‘cuz like, ‘oh, that’s just the taboo talking. Like you’re not supposed to be sick, you’re not supposed to be taking medication or stuff like that.’” (Transcript 4) | |

| MH and EDs not taken seriously until physical | There is no prevention, only intervention. Parents will usually only acknowledge the existence of MH issues when the symptoms became serious enough to present physically and/or warrant medical attention. | “I think it [eating disorders] also doesn’t get taken seriously until someone actually gets like really sick - Yeah like in our culture, they care about it after it’s already happened.” (Transcript 2) | |

| Parents’ unresolved mental health issues | Immigration trauma | Parents experienced unique hardships and struggles when they immigrated to the US. Because they came to America to provide a better life for their children, any struggles or concerns that their children have are viewed as “less than” and unjustified. | “…my parents don’t have the language to talk about mental health in the same way, in like the same language that I do. So, like my dad doesn’t really talk about it but my mom has been opening up more and more, about like, just like the trauma of immigrating. And like not having anybody here and just like rebuilding a whole life and like, just like, complete loneliness basically until I was born…But she’s not labeling it as like ‘different,’ or PTSD or anything…” (Transcript 1) |

| No permission to experience MH | Children are not allowed to experience MH concerns because parents were never given the opportunity to experience and acknowledge their own MH concerns. | “…I remember one time in high school I was so stressed because [of academic demands] …and I was like, ‘I’m stressed’… my dad overheard me saying that and he got so mad he said, ‘you have no right to say that you’re stressed, you don’t know what stress is and you don’t know what anxiety is. You don’t know what this or that is like – you don’t have a right to feel that,’ and he was like, ‘that shouldn’t even be in your vocabulary.’ So, you know it’s a thing when even the symptoms are looked down upon and they’re like, ‘no you’re supposed to be happy because you have everything you could possibly ever want.’” (Transcript 3) | |

| Provider bias | Communication barrier with PCPs | Many participants described experiences in which their PCPs were dismissive of their symptoms and experiences or even engaged in weight stigma. As a result, the participant had to self-advocate for themselves and/or a family member to receive care. | “I feel like for health professionals, I feel like they should just be more sensitive and realize that there’s a lot of different cultures coming in and everyone reacts to things differently, and there’s ways that you can talk to certain types of people and you can’t just…’cuz I’ve definitely been in situations where my mom will go to the hospital and they didn’t take her seriously…they’ll just assume we’re being too dramatic, like people from other countries, and then they won’t understand them properly….it just made me wonder, ‘oh, if she was White or something, they understood her, would they take her more seriously?’” (Transcript 2) |

| “It’s culture” | Many PCPs attributed a participant’s symptoms to their cultural background. Participants described how their PCPS often made assumptions based on the intersectionality of their identities as both a woman and a person of color. | “Every time I brought something up, my PCP was very quick to be like, ‘it’s culture.’ But you don’t know anything about the culture though… Don’t assume that we’re not going through it just ‘cuz you don’t know anything about it ‘kind-of-thing.’” (Transcript 1) | |

| Lack of knowledge about MH and EDs | Humor (MH/EDs) | MH and EDs are joked about. Both peers and parental figures will make specific jokes about eating habits (e.g., dieting, restriction) and have used “anorexia” as a derogatory term. | “Yeah…I never ate right when I was younger so my friends would always - and I was just naturally skinny to add to that – so my friends would always be like oh, ‘you’re anorexic’ and they would joke about it so much I started believing I was. Like I would joke about it and honestly I believed at some point I was because – I didn’t necessarily starve myself, I just wouldn’t eat all day. Like I’d have a cup of milk for breakfast, like maybe two bites of my lunch, and then I was picky at dinner too so I never ate…” (Transcript 7) |

| No concept of health/nutrition | Parents and older generations do not have scientific information or knowledge about nutrition, health, and exercise. | “…And so, it’s just like they [parents] don’t really care about like, health. So, I don’t know, like why – I mean, I do know why – they still want you to be skinny and all this stuff, but then like, eat the way they do and, and then like. Like the whole just eating a bag of chips and stuff, like that being OK, it’s just so wild to me. But it’s because to them, they don’t know what nutrition, what you need for this…” (Transcript 2) | |

| Parents lack MH/EDs language | Parents experience difficulty broaching the subject of MH concerns, including EDs, with their children because they do not possess the knowledge or language to understand these phenomena. | “…I feel like a lot of people don’t understand that it’s [eating disorders] a problem so they don’t know how to address it so they automatically go to what they’re most familiar with, which is like, ‘oh try this try that’ or like they like try to self-diagnose or diagnose the person whose coming to them with the problem rather than like actually recognizing that this is like probably medical or maybe psychological.” (Transcript 3) | |

| Parental self-blame | Parents avoid seeking MH care for their child because they are fearful that they will be blamed or labeled as a “bad parent.” | “…but it’s still not at the point like, ‘oh there’s actually something wrong with my child, like I need to get them help.’ They just think it’s their fault.” (Transcript 1) | |

| EDs do not exist | Because EDs are not considered real or discussed as a major concern, they are not considered a true disorder or problem. People do not view food as disordered and if a woman is viewed as “too skinny or too fat,” the solution is to “just eat more, or just eat less.” | "…like if you don't eat enough in front of other people, you get yelled at. I also don’t think parents see bulimia – like my parents don't see bulimia as an eating disorder ‘cuz they’re like, ‘oh you just ate too much, and then you threw up.’ I don’t know, they just don't see it." (Transcript 5) | |

| Suicide | Unprompted, many participants used case studies of peers in their South Asian communities who had died by suicide to illustrate their parents’ denial and lack of understanding about the seriousness of MH. | “Well like recently, one of our family members - like so she was doing her residency in [REDCATED], and um she committed suicide. It was like a family friend. And like my grandma and my parents – or like my dad, we were just like, ‘oh my god, can’t they like - how can – like the disgrace they brought to the parents, imagine how the parents are feeling,” and I was like, ‘do you realize this kind of thinking is maybe what drove her to commit suicide? Like you haven’t once said like, ‘oh I wonder what was wrong? Like oh, she had everything - she had a residency like blah blah blah.” And I’m like, ‘have you once thought that this kind of thinking is what drove her to commit suicide in the first place?’” (Transcript 4) | |

| Current generation lacks ED knowledge | Participants described particular difficulties in understanding EDs in their generation. While they acknowledged the existence of EDs, many expressed limited understanding of ED presentations, symptoms, and detection. More so, some even endorsed common ED stereotypes. | “For a lot of people you can't really tell unless like, you're them. Or they specifically tell you, because yeah, a lot of the time you can't see the symptoms or the signs yourself because like with bulimia like um, those person tend to be more extroverted, so they'll like go out to eat with you and everything will seem perfectly fine, but then they'll go to the bathroom and they'll make themselves throw up so, and you won't know, so it's like you think they're fine but they're really not. And they're don’t- people that are bulimic are not necessarily super skinny or super overweight or anything so you can't really tell.” (Transcript 5) | |

| Lack of Representation | Lack of SA representation | South Asians are rarely highlighted in MH campaigns and are thus less likely to have access to treatment and support for their ED and other concerns. South Asians are rarely included in research samples, which makes findings inconclusive and ungeneralizable to these communities. South Asian women are also not highlighted in American media. | “I guess, scientifically most of the times, I’m skeptical because most of the clinical trials are done on Caucasians, so I’m not too sure, especially for more complex disorders, that the medicine [the doctor] is giving me is going to be that effective on me just because there’s no supportive data with Asian or South Asian people.” (Transcript 1) |

Note. ED = eating disorders; MH = mental health; US = United States; PCP = primary care providers.

Barriers to Mental Health Treatment-Seeking

Theme 1: Eastern versus Western medical views.

Participants noted that older SAs (e.g., parents, relatives, community members) generally prefer Eastern medicinal traditions over Western medicine. They reported that older SAs distrust Western medications for a variety of reasons, including fears of addiction, and short- and long-term side effects. As alternatives, many parents prescribe homemade ayurvedic medicine (e.g., herbal remedies), or suggest pseudoscience cures for their children’s mental health symptoms (e.g., “Like my parents don’t go to the doctors at all because they’re like, ‘eh, we can walk around. Like we’re fine,’” Transcript 2). These recommendations usually lack empirical support and are often transmitted through social media (e.g., WhatsApp chain messages). Although participants were wary of following their parents’ unsubstantiated health tips, they were more accepting of their parents’ use of homeopathic, ayurvedic remedies.

And it’s also the fact that, especially on the Eastern side, that more natural medicine is used. It’s more ayurvedic, like that we made our own concoctions, and like that’s what we know – or we think we know what’s good for our body – and then like we come here [the US] and it’s all like pills and over-the-counter medicine. Yeah, we’re skeptical of that.

(Transcript 1)

In addition, many participants reported that their parents and older relatives viewed religion as both an explanation and intervention for mental health concerns. Many noted that when they attempted to discuss mental health concerns with their parents, they were told their problems betray a mistrust in God, or that they might be possessed.

…it’s like, ‘oh, you’re depressed? Just pray it away.’ It doesn’t do anything; there’s doctors, professionals, there to help you, but if you go there, you are crazy. ‘Oh, you’re saying you have a mental illness, are you not content with God or something like that?’

(Transcript 3)

Theme 2: Stigma.

Mental health concerns are rarely discussed in the SA community. In the infrequent cases when they are acknowledged, they are viewed as temporary, and people with these conditions may be labeled as “crazy” or “contagious.” This was related to the previous theme in which some parents attributed their children’s mental health concerns to issues with their relationship with God. Several participants reported that older SAs, including their parents, silenced conversations about mental health. This silencing was due to parents’ fear that if community members discovered their children had any mental health issue, their families would be shamed, judged, and socially ostracized. This fear of social stigma appears to maintain a culture of silence around mental health, and thus, poses a strong barrier to treatment-seeking.

…they [parents] like understand and recognize there’s a problem, but they know that the moment it goes from their inner little circle to anywhere else, it’ll spread like a wildfire and they feel like that’s gonna be shameful.

(Transcript 3)

…and then socially like, ‘oh like what are people going to say? Log kya kahenge? [What will people say?]

(Transcript 3)

Because of this culture of silence surrounding mental health, many participants reported rarely feeling comfortable confiding in their parents about their struggles, and thus, felt generally unsupported and alone. Further, participants noted that because older generations generally deny the existence of mental health concerns, including EDs, these issues are not acknowledged until symptoms become severe enough to be physically obvious and/or warrant medical attention.

…I know a lot of women who struggle with eating disorders that might be like [from] a minority group often will like tell their friends, tell an American teacher, but they won’t tell their parents. But if you’re trying to get like some kind of like institutionalized treatment, often times you have to go to your parents or someone who can help…. And I think a lot of it is like if you think there’s stigma in your community, then you are less likely to go and approach it directly.

(Transcript 7)

Theme 3: Parents’ unresolved mental health issues.

Many participants reported suspecting that their parents silently suffered from mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression. However, they also thought their parents perceived these conditions as part of life, rather than treatable illnesses. Specifically, participants noted their parents viewed these concerns as natural outcomes of the immigration process. Although parents experienced hardships when they immigrated, this process was considered a necessary cost to achieve the goal of better opportunities for their children. As such, participants discussed how parents and older generations did not allow themselves to view these experiences as potentially traumatic. Participants described bearing witness to parental suffering, and feeling parentified as a result. Furthermore, due to the extraordinary immigration-related challenges faced by older generations, many participants described experiences of having their own concerns invalidated.

…I remember one time in high school I was so stressed because [of academic demands] …and I was like, ‘I’m stressed’ … my dad overheard me saying that and he got so mad he said, ‘you have no right to say that you’re stressed, you don’t know what stress is and you don’t know what anxiety is. You don’t know what this or that is like – you don’t have a right to feel that,’ and he was like, ‘that shouldn’t even be in your vocabulary.’ So, you know it’s a thing when even the symptoms are looked down upon and they’re like, ‘no you’re supposed to be happy because you have everything you could possibly ever want.’

(Transcript 3)

Theme 4: Provider bias.

Many participants described negative experiences in which their medical providers were dismissive, culturally-insensitive, and/or fat-shaming, regardless of whether they were seeking care for a physical or mental health condition, or an ED specifically. In particular, participants reported that many PCPs attributed their symptoms to their cultural background.

Every time I brought something up, my PCP was very quick to be like, ‘it’s culture.’ But you don’t know anything about the culture though… Don’t assume that we’re not going through it just ‘cuz you don’t know anything about it ‘kind-of-thing.’

(Transcript 1)

Furthermore, participants noted it was doubly frustrating when, after surmounting numerous cultural difficulties related to help-seeking, they encountered insensitive health providers.

I think something that professionals should know is that it just takes a lot from a South Asian woman to just actually know, and just tell someone about their problems. ‘Cuz sometimes people in their family aren't understanding, like they don't really have a support system. So, for them to like take that step by themselves – it's a big enough deal without really like scaring them like, ‘oh my god you're – there’s something wrong with you!’

(Transcript 6)

Barriers to ED Treatment-Seeking

Theme 5: Lack of knowledge about mental health and EDs.

Participants noted that older SAs do not fully understand or acknowledge the existence of mental health concerns, including EDs. Consequently, many use humor to dispel discomfort surrounding the topic of EDs. Additionally, participants noted parents may avoid seeking mental health care for their child because they fear being judged as a “bad parent.” Participants indicated that this parental fear was one of the main factors that would prevent them from seeking ED treatment.

…I feel like if a White woman–if people find out that she has an eating disorder–then she goes to the hospital or something; they do what they should do, they extend their care and they help that person. And I feel like…a lot of South Asians may think about their reputation more than they do about caring about that person. Like, ‘oh, she’s in the hospital because she has an eating disorder. Now I’m seen as a bad mom… ’ So, it’s like, they care, but it’s also that aspect of their reputation that they care about too, which I feel like with White people, that’s not really how it is.

(Transcript 2)

Furthermore, participants reported that their parents have difficulty discussing EDs, because they do not have the knowledge or language relevant to these phenomena. For example, many participants noted that their parents do not consider EDs to be real problems, as they do not conceptualize eating as a behavior that can be disordered.

I don’t think I’ve ever heard a Brown household talk about eating disorders…I think with eating – like in general, in Brown households – I’ve seen, ‘oh too thin or too fat’ like that and eating – and like, weight is talked about. But eating disorders? They brush it off. It’s not even – like there might be a reason behind how you’re eating, [but] it’s just like, ‘oh, it’s not enough or it’s too much.’

(Transcript 3)

Furthermore, if a woman is viewed as “too skinny or too fat,” the solution is to “just eat more, or just eat less” (Transcript 3). Thus, ED behaviors are sometimes viewed as socially acceptable.

Theme 6: Lack of representation.

Across focus groups, participants expressed awareness of the lack of SA representation (as both patients and providers) in ED health campaigns and research specifically, and the mental health field generally. Consequently, many SA American women feel silenced, marginalized, and are more likely to minimize their ED experiences.

I feel like underrepresentation is also a big thing because if you don’t see people that are like you I guess, feeling depressed, that had anxiety like you, [then you think] ‘why am I like that, I shouldn’t be like that?’ So, you don’t feel the need to get diagnosed or tell your parents because you just feel like it shouldn’t be like that or I shouldn’t be like that. Because you don’t see people that are like you like that.

(Transcript 5)

Facilitators to Mental Health Treatment (Generally) and ED Treatment (Specifically)

The coding team identified three themes regarding potential facilitators of ED treatment-seeking, including: intergenerational mental health conversations, psychoeducation about EDs, and cultural sensitivity training for healthcare providers (see Figure 2 and Table 2). Similar to barriers to care, participants described a significant need to destigmatize mental health concerns broadly, followed by two specific recommendations for promoting ED treatment-seeking. Each theme is described in the following paragraphs.

Table 2.

Facilitators of mental health and eating disorder treatment-seeking (N=3).

| Theme | Code | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational Conversations | Change needs to start with parents’ generation | The current generation wants their parents’ generation to receive some psychoeducation about MH so that they can be better equipped to help their children and themselves. | “…fixing this problem is gonna take a long time because it’s a generational issue… And yeah, I guess trying to break the stigma somehow…[but] at the end of the day, our parents still have authority so you can try to help the kids so much, but when mom, dad, grandma, aunt, and uncle are doing the same thing, the change has to come from them as well…” (Transcript 3) |

| Optimism | Participants acknowledged that they can also spur on change and shift their parents’ thinking, in addition to MH providers. | “…instead of just putting it on like professionals to deal with it. We can start it ourselves like we, I’m pretty sure most of us have younger siblings or younger cousins we can start there. Like we can encourage them to be themselves we can encourage – we can look after them ‘cuz if we’re this far in life and we’re educated enough, we can help our younger siblings or our younger cousins deal with stuff that we shouldn’t of dealt with alone. So, we can be there for them and we can slowly branch out.” (Transcript 3) | |

| Challenging MH stigma | Participants reported a need to challenge MH stigma within South Asian communities. | “I think it takes like a few families to be like, ‘this is what happened in my family,’ and like I think as soon as it becomes more common – this is for our parents’ generation – as soon as it becomes more common people start to accept and understand and then maybe help their own families. Because right now we’re more focused on what other people think about us rather than the actual well-being of ourselves.” (Transcript 3) | |

| Parental openness | A minority of participants described how their parents were willing and open to having conversations about emotional distress and MH concerns. | “…for like my family and my extended family, if someone’s going through something it’s like known. Like everyone knows about it and like respect it. They dont’t like talk down about it. Like some of the older aunties or like you know grandmas might because they have that old mentality but I think like even like my parents and their cousins – they’re very like understanding of it and like patient with that person’s like, you know, um ‘do what they need to get done whether it’s medication or going to like doctors or something.’…So, it’s a very like mutual respect.” (Transcript 7) | |

| Peer support | Although participants rarely felt comfortable disclosing MH concerns to their parents or other community members, they did acknowledge that they were able to discuss their symptoms with peers who experienced similar issues. | “And because of that – they don’t talk about it [mental health/EDs] – it’s perpetuated, so I mean I have no one to talk to about something with and I’m glad now like my friends who are also South Asian – like we talk about it and that’s been an outlet for me because they also go through the same things, but if I had absolutely no one to talk about [it with] – which would’ve been very likely if I hadn’t had any friends that go through the same thing – then I probably wouldn’t have gotten better.” (Transcript 1) | |

| ED Psychoeducation | Psychoeducation | MH providers need to educate South Asians about the reality of MH and EDs. Participants noted that the South Asian community would be receptive to this information if it was disseminated by a South Asian doctor. | “I think persistence is one thing, ‘cuz it’s hard to get it through tradition and blood, and what we’ve been trained to think. So, I feel like it’s just slowly kind of breaking down that wall and slowly being like, ‘this is the education, this is the research.’ Presenting a lot of evidence is usually a good thing.” (Transcript 4) |

| ED Cultural Sensitivity Training for Providers | “Do your research” | Rather than making assumptions, such as “it’s culture,” women want their doctors to do their research on differential symptom presentations. | “[I] think that there [needs to] be more doctors in that field.…I know it’s hard to go to doctors and explain your diet when they dont’ understand it. Like how are you going to tell them what you eat when you don’t know how to explain it to them? Like I don’t know what goes into certain foods so how am I going to like tell a doctor what it is? I know that like when I saw a nutritionist, my parents took me to an Indian one who was from the region that we were from, so it’s like easier for me to explain to her what I eat ‘cuz when I say I eat something she like understands what goes behind it and she’s able to like tell me – whether to eat more or less or you know like how to control that.” (Transcript 7) |

| Cultural differences in symptom presentations | Participants acknowledged that MH concerns may present differently across cultural groups. | “And for psychology, it is very cultural-specific. We have different symptoms that we need to identify and having psychologists and having awareness is so important…you don’t realize you have symptoms of these illnesses because you’re told you can’t have it.” (Transcript 3) | |

| ED detection training for PCPs | Participants noted that many of their health providers did not appear to be trained in detecting EDs. When health providers do not take EDs seriously or acknowledge their existence, patients can tell. Understandably, this makes it much harder for the patient themselves to acknowledge their illness. | "I think health professionals need to find a better way to ask questions ‘cuz I feel like my pediatrician was like, ‘do you have an eating disorder?” and I’m like ‘no.’” (Transcript 5) | |

| Two-way conversation | If parents are present in the exam room with their child (i.e., less than 18 years old), then the doctor needs to address both the parents and the child. The parents should not be doing all of the talking for their child. | “The biggest problem for me was when I was younger, um, my parents would be in the room with me and my doctor would talk to them, or would like mainly talk to them about the issues I was facing, and they obviously have their own version of what, or they obviously have their own opinion of everything I’m facing – so it would just be a one-sided conversation and I wouldn’t have any input.” (Transcript 1) | |

| Parents step out of exam room | If possible, parents should be asked to leave the examination room when the doctor is assessing their child for MH and EDs | “…if they’re [parents] not there, it’s better. You can be more open.” (Transcript 1) |

Note. ED = eating disorders; MH = mental health; PCPS = primary care providers.

Facilitator of Mental Health Treatment-Seeking

Theme 1: Intergenerational conversations.

As a solution to the “stigma” and “parents’ unresolved mental health issues” barriers, participants recommended that health professionals provide older SAs psychoeducation about mental health. Further, participants suggested that providers facilitate intergenerational conversations between parents and their children about managing stress and supporting their children’s mental health. Some focus groups added that their generation could promote mental health advocacy by challenging stigma within the SA community; however, many acknowledged this shift could not gain traction without acceptance by their parents’ generation:

…fixing this problem is gonna take a long time because it’s a generational issue… And yeah, I guess trying to break the stigma somehow…[but] at the end of the day, our parents still have authority so you can try to help the kids so much, but when mom, dad, grandma, aunt, and uncle are doing the same thing, the change has to come from them as well…

(Transcript 3)

Although most participants reported difficulties confiding in their parents, a minority said their parents were open to discussing mental health concerns.

Facilitators of ED Treatment-Seeking

Theme 2: ED psychoeducation.

Participants’ most common recommendation to facilitate ED treatment-seeking was psychoeducation. They noted it would be optimal if SA-identified doctors could disseminate this information to local SA communities to increase community members’ comfort and build trust.

I think persistence is one thing, ‘cuz it’s hard to get it through tradition and blood, and what we’ve been trained to think. So, I feel like it’s just slowly kind of breaking down that wall and slowly being like, ‘this is the education, this is the research.’ Presenting a lot of evidence is usually a good thing.

(Transcript 4)

Theme 3: ED and cultural sensitivity training for providers.

To address healthcare providers’ biases, participants recommended education for general practitioners about ED etiology and symptoms. Participants remarked that many of their providers did not appear to be trained in detecting EDs. In addition, participants noted that adolescent providers (e.g., pediatricians and child psychologists), should acknowledge patients’ autonomy by talking directly to them about their healthcare (and not solely talking to parents). Furthermore, participants suggested providers ask parents to step out during examinations, enabling opportunities for more confidential ED assessments. Many described feeling uncomfortable openly discussing their concerns with providers, as their parents were often present in the room (even as adults).

Participants also felt it was essential for providers to receive cultural sensitivity training that could increase awareness of both potential cultural differences in symptom presentations, and the seriousness of “atypical” EDs. Participants reported feeling invalidated when their providers did not take EDs seriously. Because SA American women often feel dismissed by their community, it is particularly important for their providers to serve as allies in the treatment process:

And for psychology, it is very cultural-specific. We have different symptoms that we need to identify and having psychologists and having awareness is so important…you don’t realize you have symptoms of these illnesses because you’re told you can’t have it.

(Transcript 3)

Discussion

SA Americans have been excluded from research both on mental health generally, and EDs specifically (Inman et al., 2014; Iyer & Haslam, 2003, 2006). Very little information is available regarding the specific barriers to and facilitators of either general mental health, or ED-specific treatment-seeking for this population. This study used qualitative methodology with SA American women to enhance understanding of factors affecting ED treatment-seeking behaviors within this underserved group. Findings highlight several important cultural, institutional, and individual barriers to ED-treatment seeking.

In particular, barriers to ED treatment-seeking were inextricably linked to the broader issue of mental health stigma within SA culture. Participants often discussed more well-known and common mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety and suicide, in conjunction with ED concerns, frequently describing global barriers to mental health care, rather than barriers specific to ED care. One reason this might have occurred is because the focus group facilitator began the interview by first asking participants their views on mental health more broadly. This approach was used based on the recommendation from qualitative researchers (with experience working with marginalized groups), that this broad initial question could ease participants into a discussion of the more highly stigmatized topic of EDs. Another potential explanation for why current results apply both to mental issues broadly, as well as to EDs specifically, might be a function of this study’s eligibility criteria. Namely, individuals were not required to have lived experience of EDs prior to participating. Although our intention was to recruit a representative sample of the broader female SA population, we acknowledge that lack of specific lived experience could have affected participants’ responses. Alternatively, this pattern of results might also indicate participants’ relative discomfort with discussing EDs. However, we hypothesize that EDs are regarded with the same pervasive stigma assigned to all mental health conditions within SA culture (Arora et al., 2016; Kermode et al., 2009). This social and general stigmatization of mental health concerns sorely limits both accessibility to and pursuit of ED treatment services for this population. Thus, it is imperative to work towards de-stigmatizing mental health concerns broadly as a mechanism to enhance SA American women’s comfort with treatment-seeking for these conditions.

Social Stigma, Psychoeducation, and Intergenerational Conversations about EDs

Consistent with past work with SAs (Arora et al., 2016; Chaudhry & Chen, 2019; Fountain & Hicks, 2010; Inman et al., 2014; Loya et al., 2010; Rastogi et al., 2014), mental health stigma was identified as a potent treatment-seeking barrier. In addition to general mental health stigma, a particular social stigma emerged that is tied to a fear of judgement by fellow community members. Other researchers have described a similar type of stigma, called courtesy stigma, which socially devalues family members of an individual with a mental illness (Chaudhry & Chen, 2019; Corrigan & Miller, 2004; Moses, 2014; Rao & Valencia-Garcia, 2014). Study participants also noted that if a girl develops an ED while still living with her family-of-origin, her parents may avoid seeking treatment for the same reason. This fear appears to reinforce a culture of silence surrounding EDs (Wales et al., 2017). This is understandable considering that interpersonal relationships are especially valued in collectivistic cultural groups (Markus & Kitayama, 2010). Thus, the actions of any individual might be perceived as a reflection on an entire social network.

One recommendation current participants provided to mitigate the consequences of this social silencing, and facilitate help-seeking behaviors in SAs, involved creating spaces in which parents and their children could engage in productive conversations about EDs and general mental health that are grounded in evidence-based knowledge. Participants further suggested that it would be ideal if these parent-child forums could be moderated by SA health professionals.

In addition to providing general mental health knowledge, providers could facilitate ED-treatment seeking by conducting community-based psychoeducational campaigns. Considering that many cultural groups, including SAs, appear to doubt the existence of EDs in their communities (Perez & Warren, 2013), it is imperative that providers emphasize that EDs affect people of all backgrounds (Cheng et al., 2019). Furthermore, it is important to include culturally-tailored information highlighting how EDs might present differently in SAs (e.g., some “traditional” ED symptoms, such as fasting, may be considered socially acceptable in SA communities; Akgul et al., 2014; Kawamura, 2015; Khandelwal et al., 1995), as well as culturally-specific resources (e.g., names of SA providers and local ED clinics) that can connect individuals with services. Also, clinicians can culturally-adapt methods that have worked with other marginalized racial/ethnic groups, such as emphasizing the physical and medical complications associated with EDs (Yu et al., 2019); however, etiological models (e.g., emphasis on sociocultural vs. biological factors) should be tailored based on individuals’ level of acculturation and immigration status (Mokkarala et al., 2016; Rastogi et al., 2014).

Of note, religious affiliation may be especially influential in shaping SAs’ conceptualizations of mental illness. As participants reported, many older SAs, such as their parents, community members, and relatives, attributed mental illness to religious origins. Indeed, research has found that Muslim SAs may attribute mental illness to spiritual, supernatural, and divine origins (Abu-Ras et al., 2008), whereas Hindu SAs may attribute a person’s mental illness to their karma (Jilani et al., 2018). Furthermore, religious institutions may serve as a place of refuge for certain SA groups, as research indicates that SAs may feel more comfortable seeking informal counseling from religious leaders, rather than pursuing Western mental health treatment (Tummala-Narra & Deshpande, 2018). Thus, providers could consider partnering with community leaders in local gathering spaces, such as religious temples, to deliver psychoeducational programming, as these settings foster credibility and trust (Karasz et al., 2019).

Parents’ fears of judgment from other community members appear to be a significant barrier to ED disclosure and treatment-seeking for SA women. As described above, courtesy stigma might explain why parents often blame themselves for their child’s health condition (Corrigan & Miller, 2004). To mitigate this, providers could emphasize EDs’ multifaceted etiology, clarifying the roles of a multitude of factors, such as changing societal beauty norms, media pressures, and the cultural roles of food within SA communities. Furthermore, providers should emphasize parents’ essential roles in recovery, while avoiding any parent-blaming (Le Grange et al., 2010). Overall, finding ways to enhance the accessibility of ED psychoeducation appears to be key to facilitating treatment-seeking for this population.

Challenging Provider Bias via ED and Cultural Sensitivity Training

Lastly, participants identified multiple health providers’ biases as barriers to general mental health, and specific ED treatment-seeking. Each of these biases speaks to current systemic issues within the American healthcare system that dissuade SA women from help-seeking and/or receiving care for their health condition.

First, research has highlighted providers’ susceptibility to biases limiting their recognition of EDs in people of color (Abbas et al., 2010; Alegria et al., 2002; Becker et al., 2003; Marques et al., 2011). These biases appear to contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in ED treatment referrals and diagnoses. Second, participants in this study indicated that they rarely encountered SA providers trained in detecting and treating mental health concerns (including EDs), which limited their comfort in seeking care. This finding highlights a larger issue concerning the relative lack of racial and ethnic diversity among ED providers, which likely exacerbates assessment, diagnosis, and treatment health disparities (Jennings Mathis et al., 2019). However, SA providers also might be less likely to specialize in treating mental illness than their White counterparts due to the same generalized stigma that prevents their community from seeking care (Inman et al., 2014). Third, PCPs are rarely trained in ED detection, which is especially problematic, as most patients with EDs initially present to these clinicians for treatment (Mond et al., 2007; Striegel-Moore et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2000). Furthermore, SAs are also more likely to first seek care for a mental illness from a general practitioner, rather than a mental health provider (Leung et al., 2011). Fourth, even PCPs who are trained in detecting and treating EDs may miss the “atypical” presentations that often occur among SAs, such as “non-fat phobic” anorexia nervosa and psychosomatic symptoms (Anand & Cochrane, 2005; Tareen et al., 2005; Pike & Dunne, 2015). Finally, regardless of their specialty, many health providers are complicit in perpetuating weight stigma, which can be especially harmful for women of color in larger bodies (Ferrante et al., 2016). Thus, reducing weight stigma within the healthcare system may promote ED treatment-seeking for SA women.

To mitigate treatment barriers, participants recommended providers receive training in ED assessment and cultural sensitivity. Training should emphasize that EDs affect individuals regardless of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or cultural background (Cheng et al., 2019; Schaumberg et al., 2017), and these conditions can present differently across groups, including SAs (Kawamura, 2015; Mustafa et al., 2018; Pike & Dunne, 2015; Rodgers et al., 2018; Tareen et al., 2005). Clinicians should consider the impact of their own weight biases on treatment (Kersbergen & Robinson, 2019), and perhaps treatment teams could hire SA women with lived experiences of EDs to assist with training and treatment adaptations. These recommendations are consistent with others’ suggestions that providers strive to practice cultural humility – an approach that encourages providers to adopt a curious, open-minded, and reflexive stance that is grounded in collaboration and disrupting power imbalances, rather than making assumptions about a client’s values, lived experiences, and/or worldviews (Chang et al., 2012; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Strengths & Limitations

This study’s strengths include use of a qualitative design to enhance understanding of culturally-specific barriers to and facilitators of ED treatment for a vulnerable population. Although many results are similar to those found in previous studies of cultural competency in mental health treatment, this is one of the few studies conducted with a SA American sample. It is important to investigate these issues within specific ethnic subgroups, as recommendations emerging from studies conducted with other groups might not be generalizable.

Despite these strengths, findings should be interpreted within the context of certain limitations. The small, all-female sample limits generalizability. Future work on this topic should include other gender groups, and explore how gender socialization practices (e.g., emphasis on traditional gender roles) may influence individuals’ perceptions of mental illness and help-seeking. An additional limitation is that, although all participants had lived in the US for at least three years, we did not ask whether individuals identified as international students, which could have impacted their responses, especially those pertaining to their family-of-origin, generational differences, and understanding of mental health conditions. Future research should collect demographic information on generational status, country-of-origin, and/or immigration status (Inman et al., 2014). In terms of future directions, researchers should also consider participants’ cultural identity (e.g., the extent to which they identify with South Asian and American values), their parents’ level of acculturation, and the ways in which these variables might impact understanding of mental illnesses, including EDs (Iyer & Haslam, 2003; Tummala-Narra & Deshpande, 2018). Further, no participants from the Maldives or Bhutan were represented; thus, results might not generalize to these specific populations. Considering the aims of the current investigation, coupled with past documentation of low research participation and low ED treatment-seeking rates amongst SAs (Fountain & Hicks, 2010; Kennedy et al., 2004; Quay et al., 2017), this study was intentionally not conducted in a clinical setting. Future work should replicate this study with a clinical sample. Finally, given that the first author both developed the interview guide and moderated focus groups, there might be some bias that influenced data interpretation. However, checks by a process observer, other ethnically diverse coders, and a participant on the research team, mitigate these concerns.

Conclusions

SA American women face multiple family, community, and institutional barriers to mental health treatment, including ED treatment. These barriers likely coalesce to perpetuate treatment disparities. One of the most robust barriers to treatment-seeking for any mental health concern, including an ED, is pervasive mental illness stigma within the SA community. Thus, efforts to improve ED treatment access for SA American women should involve: (a) campaigns to destigmatize mental health more broadly, (b) collaboration with SA communities to develop and disseminate resources, and (c) provider training in culturally-sensitive clinical practices for ED detection and treatment.

What is the public significance of this article?

In this qualitative study, South Asian American women were asked to discuss their perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of eating disorders treatment-seeking for their group. Findings indicate that South Asian women living in the United States face multiple family, community, and institutional barriers to treatment-seeking for all mental health issues, including eating disorders, which intersect to perpetuate treatment disparities.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Kristina Hood, Maghboeba Mosavel, Faika Zanjani, Shillpa Naavaal, and Patricia Kinser for their assistance with the study design and feedback. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Ms. Harlean Bajwa, who volunteered her time to assist with this project. Most importantly, we express our deepest gratitude to the brave women who took the time to share their stories with us.

Funding

We would like to thank Dr. Aashir Nasim and the VCU Institute for Inclusion, Inquiry and Innovation (iCubed) for their generous funding support for this study. Neha Goel was also supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health grant F31 MD015679.

Appendix A

Focus Group Interview Guide

How is mental health discussed within the South Asian community?

- How are eating disorders talked about within the South Asian community, if at all?

- Probes: How are eating disorders perceived within the South Asian community?

- Are they concealed?

- Please describe any physical characteristics and values that you associate with a South Asian woman with an eating disorder.*

- Probe: Listen for any differences/similarities between descriptions of White and South Asian women.

- What do you think are some of the barriers to eating disorders treatment for South Asian women?

- Probe: Listen for family, structural, health barriers, lack of knowledge (e.g., do not perceive eating disorders as problem)

What do you think are some things that health professionals can do to help more South Asian women seek treatment for an eating disorder?

What do you think is important for health professionals to know about preventing eating disorders within the South Asian community?

Were there any areas that I did not touch upon or something that you thought I would bring up but did not?

Note. Data for the current study were derived from a larger qualitative investigation assessing South Asian American women’s conceptualizations of body image and eating disorders (see Goel et al., 2021). As such, this interview guide was amended to reflect only the questions that asked about barriers to and facilitators of eating disorders treatment. * After conducting the first three focus groups, the first and last authors met to review the interview guide and decided to replace question 3 with the following: “What is an ‘eating disorder?’ Probes: What do your parents think is an eating disorder? What are the differences between your generation and your parents’ generation?”

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abbas S, Damani S, Malik L, Button E, Aldridge S, & Palmer RL (2010). A comparative study of South Asian and non-Asian referrals to an eating disorders service in Leicester, UK. European Eating Disorders Review, 18, 404–409. 10.1002/erv.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Ras W, Gheith A, & Cournos F (2008). The imam’s role in mental health promotion: A study at 22 mosques in New York City’s Muslim community. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3, 155–176. 10.1080/15564900802487576 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akgul S, Derman O, & Kanbur ON (2014). Fasting during Ramadan: A religious factor as a possible trigger or exacerbator for eating disorders in adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 905–910. 10.1002/eat.22255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, & Ortega AN (2002). Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services, 53(12), 1547–1555. 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand AS, & Cochrane R (2005). The mental health status of South Asian women in Britain: A review of the UK literature. Psychology and Developing Societies, 17(2), 195–214. 10.1177/097133360501700207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, & Nielsen S (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724–731. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora PG, Metz K, & Carlson CI (2016). Attitudes towards professional psychological help seeking in South Asian students: Role of stigma and gender. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44, 263–284. 10.1002/jmcd.12053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Arrindell AH, Perloe A, Fay K, & Striegel-Moore RH (2010). A qualitative study of perceived social barriers to care for eating disorders: Perspectives from ethnically diverse health care consumers. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43, 633–647. 10.1002/eat.20755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AE, Franko DL, Speck A, & Herzog DB (2003). Ethnicity and differential access to care for eating disorder symptoms. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33, 205–212. 10.1102/eat.10129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia S, & Ram A (2018). South Asian immigration to United States: A brief history within the context of race, politics, and identity. In Perera MJ, & Chang EC (Eds.), Biopsychosocial approaches to understanding health in South Asian Americans (pp. 15–32). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, & Striegel-Moore RH (2006). Help seeking and barriers to treatment in a community sample of Mexican American and European American women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 154–161. 10.1002/eat.20213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Perera MJ, & Kupfermann Y (2014). Predictors of eating disturbances in South Asian American females and males: A look at negative affectivity and contingencies of self –worth. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5(3), 172–180. 10.1037/a0031627 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E-S, Simon M, & Dong X (2012). Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 17. 269–278. 10.1007/s10459-010-9264-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry T, & Chen SH (2019). Mental illness stigmas in South Asian Americans: A cross-cultural investigation. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 154–165. 10.1037/aap0000141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ZH, Perko VL, Fuller-Marashi L, Gau JM, & Stice E (2019). Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eating Behaviors, 32, 23–30. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]