Non-Hispanic (NH) Black and Hispanic persons with multiple myeloma (MM) face multiple health-related disparities that include lower access to novel therapies and under-utilization of autologous stem cell transplantation [1, 2]. Differences in biology may be associated with different clinical presentations and/or outcomes [3, 4]. MM is more common in NH Black persons. Spinal cord compression (SCC) is a medical emergency for which MM was reported to be the third most prevalent underlying cancer diagnosis associated with SCC hospitalizations [5]. Racial/ethnic differences in the rates of SCC in patients with MM were not previously reported. Our study aimed to study if such differences exist for patients with MM admitted with SCC in the U.S.

We conducted a 12-year retrospective analysis of inpatient hospitalizations from 2008 to 2019 using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data, provided by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The study sample included the occurrence of MM in the discharge records of adults (18 + years). The primary end-point of the study was SCC. The ninth and tenth editions of the international classification of diseases (ICD-09 and ICD-10, respectively) were used to identify MM and SCC diagnoses in patient records. MM was identified using ICD-09 codes—203.xx and ICD-10 codes—C90.xx, whereas SCC was identified using ICD-09 codes—336.9, 733.90, V12.49 and ICD-10 codes—G95.20, C79.51, Z86.69.

The covariates included in this study were patient socio-demographic characteristics such as patients’ age—categorized into 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65 + years; race/ethnicity – categorized as NH White, NH-Black, Hispanic, other; gender—female or male; zip code–based median household income—lowest, 2nd, 3rd and highest quartiles; primary insurance—Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, other; hospital characteristics such as bed size—classified as small, medium and large; hospital location and teaching status—grouped as rural, urban teaching and urban non-teaching; hospital region—Northeast, Midwest, South and West.

The analysis for this study was generated using R version 3.5.1 (University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand), R Studio Version 1.1.423 (Boston, MA). Due to the de-identified nature of the NIS, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Institutional Review Board (IRB) classified this study as being exempted from IRB approval. We conducted descriptive statistics to examine the patient and hospital characteristics associated with MM and SCC in MM hospitalizations. We also calculated the prevalence of MM-related hospitalizations and SCC in MM cases. All of the hospitalizations were weighted to account for the complex sampling design of the NIS, which allowed for the generation of national estimates.

To identify and describe temporal changes in the rates of SCC in MM-related hospitalizations during the 12-year study period, joinpoint regression was utilized. Each joinpoint indicated a change in the trend, and an average annual percent change (AAPC) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated to characterize how the rate of the outcome (SCC in MM cases) changed during the entire study duration. Lastly, adjusted survey logistic regression models were utilized to examine the hospitalization factors associated with SCC. All patient and hospital characteristics were used for adjustment in the model. All statistical tests were two-tailed with type-I error rate set at 5%.

Of 368,188,112 hospitalizations, 1,247,364 (0.34%) were related to MM. These were more prevalent in older adults, males, and NH-Blacks. Of MM hospitalizations, 56,902 (4.6%) were associated with SCC diagnosis.

MM hospitalizations were more common in NH Blacks (5 per 1000 hospitalizations) compared to NH-Whites (3.3 per 1000 hospitalizations) and Hispanics (2.6 per 1000 hospitalizations). SCC-related hospitalizations in patients admitted with MM were more common in NH-Whites (4.9 per 100 MM hospitalizations) compared to NH-Blacks and Hispanics (4.2 and 4 per 100 MM hospitalizations, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of multiple myeloma and spinal cord compression hospitalizations

| Overall | Multiple Myeloma | Spinal cord compression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 368,188,112 | N = 1,247,364, % = 0.34 | Prevalence per 1000 hospitalizations | N = 56,902, % = 4.6 | Prevalence per 100 multiple myeloma hospitalizations | |

| Age | |||||

| 18–34 years | 71,186,975 | 4391 | 0.1 | 154 | 3.5 |

| 35–49 years | 55,955,733 | 66,129 | 1.2 | 1882 | 2.8 |

| 50–64 years | 92,401,226 | 386,176 | 4.2 | 13,910 | 3.6 |

| 65 + years | 148,644,178 | 790,668 | 5.3 | 40,955 | 5.2 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| NH-White | 232,165,261 | 756,239 | 3.3 | 36,816 | 4.9 |

| NH-Black | 50,463,485 | 254,780 | 5.0 | 10,686 | 4.2 |

| Hispanic | 36,554,986 | 93,738 | 2.6 | 3753 | 4.0 |

| NH-Other | 21,215,167 | 60,445 | 2.8 | 2653 | 4.4 |

| Missing | 27,789,212 | 82,164 | 3.0 | 2995 | 3.6 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 151,625,231 | 681,138 | 4.5 | 30,702 | 4.5 |

| Female | 216,371,220 | 565,843 | 2.6 | 26,170 | 4.6 |

| Missing | 191,661 | 385 | 2.0 | 30 | 7.8 |

| Zip Income quartile | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 107,364,203 | 328,946 | 3.1 | 14,424 | 4.4 |

| 2nd quartile | 94,086,154 | 299,811 | 3.2 | 13,112 | 4.4 |

| 3rd quartile | 85,746,861 | 300,416 | 3.5 | 14,004 | 4.7 |

| Highest quartile | 72,973,160 | 294,965 | 4.0 | 14,507 | 4.9 |

| Missing | 8,017,734 | 23,228 | 2.9 | 855 | 3.7 |

| Primary payer | |||||

| Medicare | 170,390,168 | 832,941 | 4.9 | 38,281 | 4.6 |

| Medicaid | 61,543,837 | 76,271 | 1.2 | 2858 | 3.7 |

| Private Insurance | 104,863,205 | 291,740 | 2.8 | 12,026 | 4.1 |

| Self-Pay | 30,706,819 | 44,144 | 1.4 | 3604 | 8.2 |

| Missing | 684,083 | 2270 | 3.3 | 133 | 5.9 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Routine | 240,913,151 | 645,493 | 2.7 | 6359 | 1.0 |

| Transferred | 66,300,428 | 280,060 | 4.2 | 16,120 | 5.8 |

| Died | 8,099,712 | 65,646 | 8.1 | 20,278 | 30.9 |

| DAMA | 4,837,844 | 5898 | 1.2 | 80 | 1.4 |

| Other | 47,809,172 | 249,413 | 5.2 | 14,010 | 5.6 |

| Missing | 227,805 | 856 | 3.8 | 55 | 6.4 |

| Hospital bed size | |||||

| Small | 59,596,686 | 174,693 | 2.9 | 7680 | 4.4 |

| Medium | 99,144,773 | 303,922 | 3.1 | 14,167 | 4.7 |

| Large | 208,082,480 | 765,079 | 3.7 | 34,920 | 4.6 |

| Missing | 1,364,173 | 3671 | 2.7 | 135 | 3.7 |

| Hospital location and teaching status | |||||

| Rural | 39,229,092 | 94,723 | 2.4 | 3680 | 3.9 |

| Urban non-teaching | 119,375,005 | 323,358 | 2.7 | 13,621 | 4.2 |

| Urban teaching | 208,219,843 | 825,614 | 4.0 | 39,466 | 4.8 |

| Missing | 1,364,172 | 3671 | 2.7 | 135 | 3.7 |

| Hospital region | |||||

| Northeast | 70,796,846 | 264,720 | 3.7 | 11,693 | 4.4 |

| Midwest | 83,671,391 | 287,726 | 3.4 | 12,672 | 4.4 |

| South | 143,348,402 | 476,550 | 3.3 | 21,636 | 4.5 |

| West | 70,371,473 | 218,369 | 3.1 | 10,901 | 5.0 |

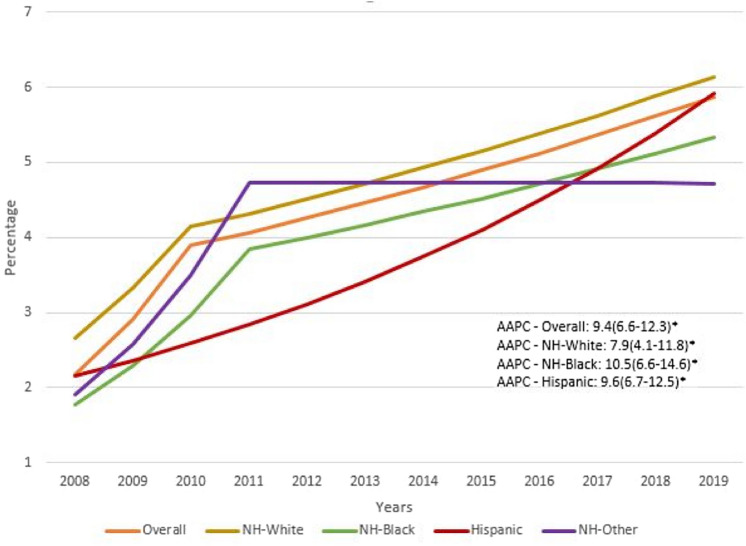

AAPC showed an uptrend for all racial/ethnic groups and was higher in NH-Blacks when compared to both Hispanics and NH-Whites (10.5, 9.6 and 7.9, respectively p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). Despite the higher AAPC in NH- Blacks and Hispanics, NH-Whites continued to have the highest rate of SCC in MM hospitalizations. Multi-variable adjusted survey logistic regression for patient’s gender, age, income quartile, primary payer, and comorbidities showed lower odds ratio (OR) of SCC in NH-Blacks (OR 0.83 (95% CI 0.78–0.88) and Hispanics (OR 0.83 (95% CI 0.76–0.91) when compared to NH-Whites.

Fig. 1.

Trends in the rates of spinal cord compression in multiple myeloma hospitalizations 2008–2019

Our study is the first to report on racial/ethnic differences of the rates of SCC in hospitalized MM patients using a representative large national sample. MM is a heterogeneous disease, and such clinical difference can be related to variability in the molecular subtype of MM and/or other clinical features of MM. Future analysis from the UAMS MM database is being performed to help in exploring biological differences in different racial/ethnic groups according to the molecular MM subtype and/or clinical presentation.

We found that the rates of SCC in patients with MM are overall increasing and is lower in NH-Blacks and Hispanics when compared to NH-Whites. SCC is a medical emergency that can result in pain and potentially irreversible loss of neurologic function. Extradural SCC can be related to extramedullary plasmacytoma or a bone fragment secondary to a pathological vertebral fracture. Early detection and intervention may help in avoiding permanent paraplegia. The increased rates of SCC in patients with MM found in our study may be related to better recognition and/or diagnosis of SCC. Other potential explanations may be related to the change in treatment landscape and/or longer survival of MM patients.

Using data from the NIS has some limitations, such as lack of individual patient data, inability to categorize other minor ethnic groups or patients who self-identify as multi-racial and the consideration of recurrent hospitalizations as distinct observations. Moreover, data on outpatient consultations are not available and the recognition of the diagnosis of SCC in the outpatient setting is increasing [6].

Our analysis showed that the rates of SCC in patients with MM are overall increasing and is lower in NH-Blacks and Hispanics when compared to NH-Whites. This may be related to different biology in different ethnic/racial groups which needs to be further explored in future studies.

Author Contributions

SAH conceived the research idea. DD performed statistical analyses. SAH wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the methodology and analyses, and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors report no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Due to the de-identified nature of the NIS, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) Institutional Review Board (IRB) classified this study as being exempted from IRB approval.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Al Hadidi S, Dongarwar D, Salihu HM, et al. Health disparities experienced by Black and Hispanic Americans with multiple myeloma in the United States: a population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(13):3256–3263. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1953013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ailawadhi S, Frank RD, Advani P, et al. Racial disparity in utilization of therapeutic modalities among multiple myeloma patients: a SEER-medicare analysis. Cancer Med. 2017;6(12):2876–2885. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker A, Braggio E, Jacobus S, et al. Uncovering the biology of multiple myeloma among African Americans: a comprehensive genomics approach. Blood. 2013;121(16):3147–3152. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-443606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillmore NR, Cirstea D, Munjuluri A, et al. Lack of differential impact of del17p on survival in African Americans compared with White patients with multiple myeloma: a VA study. Blood Adv. 2021;5(18):3511–3514. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020004001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mak KS, Lee LK, Mak RH, et al. Incidence and treatment patterns in hospitalizations for malignant spinal cord compression in the United States, 1998–2006. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(3):824–831. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rades D, Huttenlocher S, Dunst J, Bajrovic A, Karstens JH, Rudat V, Schild SE. Matched pair analysis comparing surgery followed by radiotherapy and radiotherapy alone for metastatic spinal cord compression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):3597–3604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.