Abstract

Background

The distribution of ovarian tumour characteristics differs between germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers and non-carriers. In this study, we assessed the utility of ovarian tumour characteristics as predictors of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity, for application using the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) variant classification system.

Methods

Data for 10,373 ovarian cancer cases, including carriers and non-carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variants, were collected from unpublished international cohorts and consortia and published studies. Likelihood ratios (LR) were calculated for the association of ovarian cancer histology and other characteristics, with BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity. Estimates were aligned to ACMG/AMP code strengths (supporting, moderate, strong).

Results

No histological subtype provided informative ACMG/AMP evidence in favour of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity. Evidence against variant pathogenicity was estimated for the mucinous and clear cell histologies (supporting) and borderline cases (moderate). Refined associations are provided according to tumour grade, invasion and age at diagnosis.

Conclusions

We provide detailed estimates for predicting BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity based on ovarian tumour characteristics. This evidence can be combined with other variant information under the ACMG/AMP classification system, to improve classification and carrier clinical management.

Subject terms: Breast cancer, Genetic testing, Breast cancer, Epidemiology

Introduction

Ovarian cancer can be classified based on tumour origin into epithelial (~90% of all cases [1]), sex cord/stromal and germ cell. The epithelial cases differentiate into five main histological subtypes (“histotypes”), including high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC), which is the most frequent subtype [2], low-grade serous carcinomas (LGSC), mucinous, endometrioid and clear cell ovarian cancers [3]. Rarer forms of epithelial ovarian cancer such as transitional cell or mesenchymal and mixed-epithelial carcinomas may also occur [3]. Due to their differences in morphological, molecular and clinical characteristics [4], ovarian cancer histotypes are considered different diseases [5].

Several genes have been associated with increased risk of ovarian cancer, including BRCA1 and BRCA2 [6], PALB2, BRIP1 [7], RAD51C and RAD51D [8], with the largest percentage of cases (10-15%) being attributable to germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 or BRCA2 [9]. Previous findings have suggested that the distribution of ovarian cancer histopathology subtypes differs in germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers, compared to non-carriers, with a similar distribution associated with pathogenic variants for the two genes [10]. Germline pathogenic variants in the two genes occur predominantly in patients diagnosed with HGSC, where the probability of finding a BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant reaches as high as 25.2% [11]. Identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants is lower for patients with endometrioid carcinomas (4.17–10.3% [12, 13]), LGSC (1.2–6.0% [14]) and clear cell carcinomas (2.8–9.1% [15, 16]). Earlier work also suggests that germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants are unlikely to be found in patients with tumours of mucinous histology (0 to 4% [17–19]). Borderline tumours, a separate entity of non-invasive epithelial ovarian cancers, are also characterised by a low frequency of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline pathogenic variants [10]. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [20], American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [21] as well as others [22], recommend germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing for all epithelial ovarian cancer patients irrespective of histology. Other national and international medical societies and panels suggest selective testing for HGSC or non-mucinous ovarian cancer histological subtypes, due to the higher probability of finding a BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant [23, 24].

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing applied for the identification of high-risk individuals will often (5–10%) identify variants of uncertain significance (VUS) [25]. VUS are characterised by insufficient evidence for their association with disease pathogenicity and consequent clinical uncertainty in making informed decisions on disease management [26, 27]. It is recommended that VUS detection is not incorporated in patient risk assessment, and carriers are managed according to their clinical features and family history, which reduces the possibility of receiving risk-reducing interventions being offered to carriers of pathogenic variants [28, 29]. To facilitate VUS classification efforts, the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) groups have developed standards and guidelines that are widely applied by clinical labs. This system weights independent lines of evidence for and against variant pathogenicity as ‘very strong’, ‘strong’, ‘moderate’ and ‘supporting’ [30, 31]. These strengths are combined based on a scoring system of criteria to classify variants. The evidence considered may include variant location, predicted coding effect, functional data, variant co-segregation with disease or variant frequency in affected and non-affected individuals. Recently, the model was transformed into a Bayesian framework, in which weights were aligned to pathogenic and benign Likelihood ratio (LR) evidence [32].

In addition, the Multifactorial Likelihood model, applied by the Evidence‐based Network for the Interpretation of Germline Mutant Alleles (ENIGMA) consortium, also has been used to weight different evidence types for BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant classification efforts [33, 34]. For a given variant, the model calculates the posterior probability of pathogenicity, in a Bayesian quantitative classification framework that integrates multiple independent lines of evidence for the association of a variant with pathogenicity, measured by LRs, with calibrated prior probabilities of pathogenicity determined through in silico predictions [35].

Despite the observed associations between BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline pathogenic variant status with ovarian tumour characteristics, currently VUS interpretation efforts do not consider ovarian tumour pathology. We performed analyses on a large collection of data from ovarian cancer cases, including BRCA1 and BRCA2 (likely) pathogenic variant carriers and non-carriers, to assess histology and other tumour characteristics as predictors of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity, with the aim of standardising the application of this evidence in clinical variant curation using the ACMG/AMP classification system, to inform the future interpretation of VUS in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Materials and methods

Data collection and selection criteria

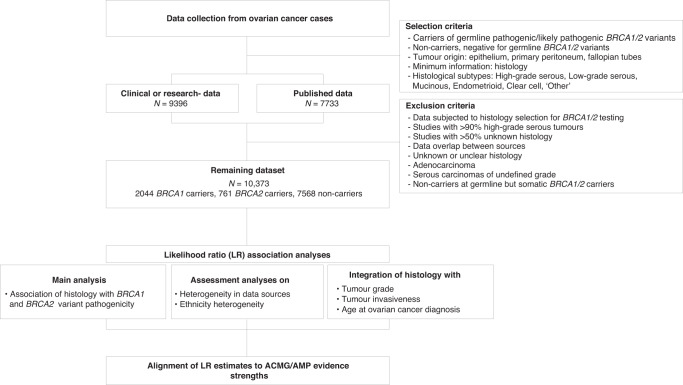

An overview of the data collection process is shown in Fig. 1, where the selection and exclusion criteria are stated. In this study, data from ovarian cancer cases were collected (ovarian epithelium, primary peritoneum or fallopian tubes as primary sites) from reported germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant carriers and individuals who tested negative for germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 (likely) pathogenic variants (non-carriers), with known histology information. Variant class (pathogenic or likely pathogenic) was based on the classification assigned by contributing sources at the time of collection. The main tumour information analysed was ovarian tumour histology, where the histological subtypes ('histotypes') considered were in accordance with the most recent ovarian tumour classification system defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [3]. Only data falling into these histological categories were considered. These included: high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC), low-grade serous carcinomas (LGSC), mucinous carcinomas, endometrioid carcinomas, clear cell carcinomas and the ‘other’ category. The ‘other’ category comprised rare forms of ovarian cancer not belonging to the above-mentioned subtypes and included tumours defined as: ‘other’ by data sources not specifying tumour histology; mixed-epithelial carcinomas; carcinosarcomas; transitional cell carcinomas (Brenner tumours); undifferentiated or poorly differentiated carcinomas; squamous cell carcinomas.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of study design and methods.

Carriers refer to individuals with a reported germline pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Non-carriers refer to individuals tested negative for BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 in germline. The ‘other’ category comprised rare forms of ovarian cancer not belonging to any of the other subtypes, including tumours defined as: ‘other’ by data sources not specifying tumour histology; mixed-epithelial carcinomas; carcinosarcomas, transitional cell (Brenner tumours), undifferentiated or poorly differentiated; squamous cell. HGSC high-grade serous carcinoma, LGSC low-grade serous carcinoma.

Data sources included clinically- or research-tested data, as well as data from published studies. Specifically, we initially collected data for 9396 individuals from clinical or research sources, subjected to germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing, from the CIMBA (Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2) [36] and OTTA (Ovarian Tumour Tissue Analysis) [37] consortia, the AOCS (Australian Ovarian Cancer Study) study [38] and collaborators of the ENIGMA consortium [34]. Data were collected using a predefined variable template, requesting information on the gene affected, classification of the detected variant, tumour invasion, histology, stage (FIGO), grade, variant nomenclature, ethnicity, age at ovarian cancer diagnosis and age at breast cancer diagnosis (if any). To collect relevant data from published studies, a literature search was conducted within the PubMed database searching for keywords such as ‘ovarian cancer’ and/or ‘ovarian cancer histology’ in combination with ‘BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 frequency’ or ‘predisposition’ (Supplementary Table S1). A total of 20 published studies meeting the study’s selection criteria, comprising 7733 ovarian cancer cases subjected to germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing, were used.

Exclusion criteria

Of the data collected, sites with a proportion of HGSCs over 90% and/or studies where the selection was applied for BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing based on HGSC or non-mucinous histology were excluded from the dataset to account for potential selection bias [11, 17, 38–41]. Sources with a high proportion of unknown histology (≥50%) were also excluded. Overlaps between consortia or study groups (CIMBA, ENIGMA) and published studies were removed. Finally, tumour data of unknown/unclear, inconsistent, adenocarcinoma histology (representing carcinomas that cannot be allocated with certainty within major categories) and serous of undefined tumour grade information, were removed. Data reported as ‘other’ were comprehensively reviewed when such information was available and reclassified into appropriate categories or excluded. Additionally, individuals with somatic pathogenic variants (if this information was provided) or reported VUS in the non-carrier group, were removed. The final dataset consisted of 10,373 cases (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses performed in this study are summarised in Fig. 1. As part of the main analysis, ovarian tumour histology was assessed as a predictor of germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant status by defining likelihood ratio (LR) estimates. Data were grouped for BRCA1 carriers, BRCA2 carriers and non-carriers (BRCA0), and histology prevalence was determined for each group. LRs were calculated for each histological subtype by comparing their frequency between BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers and non-carriers:

where and

BRCAi = 1, 2 denotes the number of BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant carriers, respectively, for a given histological subtype, and BRCA0 denotes the number of non-carriers for the same histological subtype.

The variance of ln(LR) was calculated following Koopman et al. [42]:

Assuming a normal distribution for ln(LR), a 95% Confidence Interval (CI) was determined to assess the significance of the LR estimates obtained by:

Significant LR estimates, i.e., not spanning 1, suggested nominal significance, and potential for use as evidence following the ACMG/AMP system or the Multifactorial Likelihood model.

Using the same method, additional analyses were conducted, to assess differences in histological associations between clinically- or research-tested data and literature-derived data, as well as compare histological associations between Asian and European-origin ancestries. Other races and ancestries, including Hispanic (N = 302) and African (N = 14), did not provide informative predictions due to the low number of tumour data points available. Furthermore, histological associations were refined by other tumour and/or patient characteristics. First, tumour grade characteristics were refined as appropriate for each histotype. Mucinous, endometrioid, and ‘other’ histological subtypes were categorised as grade 1 (well-differentiated), grade 2 (moderately differentiated) and grade 3 (undifferentiated or poorly differentiated). Serous tumours, i.e., HGSC and LGSC were already separated according to a two-tier system. Clear cell was not refined by grade, since they are, by definition, high-grade [3, 43]. Histological subtype data were also combined with known information on tumour invasion (invasive or borderline). Due to the small number of borderline cases collected, borderline tumours were assessed separately as a single category without considering histology. Finally, age at ovarian cancer diagnosis (before and at/after the age of 50 years) was assessed in combination with histological subtype information, where tumours of unknown age at diagnosis were removed.

ACMG/AMP LR evidence strength alignment

To determine the strength of the associations derived, LR values were aligned to the evidence values of the Bayesian framework of the ACMG/AMP system [32]. The strengths favouring variant pathogenicity included: very strong pathogenic, LR ≥ 350; strong pathogenic, 18.70 ≤ LR <350; moderate pathogenic, 4.33 ≤ LR <18.70; and supporting pathogenic, 2.08 ≤ LR <4.33. Evidence against variant pathogenicity were inferred using the inverse of the ranges proposed for the pathogenic strength evidence: very strong benign, LR < 0.00285; strong benign, 0.00285 ≤ LR < 0.053; moderate benign, 0.053 ≤LR <0.23; and supporting benign, 0.23 ≤LR < 0.48. We defined informative evidence as associations with statistically significant CI (i.e., not including 1). Categories having LR values within the range of 0.48 ≤ LR < 2.08 were referred as non-informative.

Results

Clinicopathological characteristics

The assembled dataset consisted of 10,373 ovarian cancer cases, including 2044 germline BRCA1 carriers, 761 germline BRCA2 carriers and 7568 non-carriers (based on germline testing) (Supplementary Table S2). Patient clinicopathological characteristics are shown in Table 1. The most frequent histotype was HGSC (70.9%), followed by endometrioid (9.7%), clear cell (6.3%), LGSC (4.9%), ‘other’ (4.7%), and mucinous (3.5%) histotypes. In Supplementary Table S3, histological subtypes are separated by tumour stage (FIGO), grade and age range at ovarian cancer diagnosis. Patient age at ovarian cancer diagnosis ranged from 18 to 92 years.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the ovarian cancer case data collected.

| Clinicopathological characteristics | BRCA1 carriers, N (%) | BRCA2 carriers, N (%) | Non-carriers, N (%) | Total N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total data | 2044 | 761 | 7568 | 10,373 |

| Age in years at OC diagnosis | ||||

| <30 | 6 (0.4) | 5 (0.8) | 105 (3.4) | 119 (2.2) |

| 30–39 | 170 (9.9) | 11 (1.8) | 245 (7.9) | 426 (7.9) |

| 40–49 | 670 (39.1) | 102 (17.0) | 563 (18.2) | 1335 (24.7) |

| 50–59 | 559 (32.6) | 215 (35.8) | 964 (31.2) | 1738 (32.1) |

| 60–69 | 251 (14.6) | 199 (33.2) | 833 (27.0) | 1283 (23.7) |

| >70 | 58 (3.4) | 68 (11.3) | 379 (12.3) | 505 (9.3) |

| N/A | 330 | 161 | 4479 | 4970 |

| Tumour grade | ||||

| Grade 1 | 55 (3.5) | 29 (5.4) | 401 (14.7) | 485 (10.1) |

| Grade 2 | 281 (18.0) | 91 (16.9) | 389 (14.3) | 762 (15.8) |

| Grade 3 | 1223 (78.4) | 418 (77.7) | 1934 (71.0) | 3575 (74.1) |

| N/A | 485 | 223 | 4846 | 5554 |

| Tumour histology | ||||

| HGSC | 1578 (77.2) | 597 (78.4) | 5183 (68.5) | 7358 (70.9) |

| LGSC | 58 (2.8) | 23 (3.0) | 429 (5.7) | 510 (4.9) |

| Mucinous | 21 (1.0) | 14 (1.8) | 325 (4.3) | 361 (3.5) |

| Endometrioid | 226 (11.1) | 65 (8.5) | 713 (9.4) | 1004 (9.7) |

| Clear cell | 38 (1.9) | 15 (2.0) | 605 (8.0) | 658 (6.3) |

| ‘Other’ | 123 (6.0) | 47 (6.2) | 313 (4.1) | 485 (4.7) |

| Tumour Invasion | ||||

| Invasive | 1468 (99.5) | 530 (99.1) | 2755 (94.8) | 4754 (96.6) |

| Borderline | 7 (0.5) | 5 (0.9) | 152 (5.2) | 166 (3.4) |

| N/A | 569 | 226 | 4661 | 5456 |

N number of data points, OC ovarian cancer, HGSC high-grade serous carcinomas, LGSC low-grade serous carcinomas, N/A not available.

The above data are based on 10,373 cases, including 2044 BRCA1 carriers, 761 BRCA2 carriers and 7568 non-carriers. In brackets, the frequency of the clinicopathological characteristics in all each group with known information is provided. The ‘other’ category denominates rare forms of ovarian cancer not belonging to any of the other subtypes, including tumours defined as: ‘other’ by data sources not specifying tumour histology; mixed-epithelial; carcinosarcomas; transitional cell (Brenner tumours); undifferentiated or poorly differentiated; squamous cell.

Tumour histology association analysis

Ovarian cancer histological subtypes were assessed for their potential utility in future prediction of germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant pathogenicity. Detailed LR estimates derived are provided in Table 2. Under the ACMG/AMP system, no histological subtype provided informative evidence in favour of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity. Evidence against BRCA1 pathogenicity was estimated for the mucinous (LR: 0.24 (95% CI: 0.15–0.37), supporting evidence) and clear cell (LR: 0.23 (95% CI: 0.17–0.32), supporting evidence) histotypes. Similarly, evidence against BRCA2 variant pathogenicity was derived for the mucinous (LR: 0.43 (95% CI: 0.25–0.73), supporting evidence) and clear cell histological subtypes (LR: 0.25 (95% CI: 0.15–0.41), supporting evidence). Histotypes failing to provide informative ACMG/AMP evidence, provided statistically significant LR estimates, suggestive of suitability to be included in Multifactorial Likelihood modelling (where there are no limitations set for individual LRs included). Specifically, LR estimates in favour of pathogenicity were identified for the HGSC and ‘other’ histotypes for BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the endometrioid histotype for BRCA1. Evidence against pathogenicity was also identified for LGSC for BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Table 2.

Likelihood ratio analysis for the evaluation of ovarian cancer histological subtypes in association with BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant status.

| BRCA1 carriers | BRCA2 carriers | Non-carriers | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histological subtypes | N (%) | LR (95% CI) | ACMG/AMP strength | N (%) | LR (95% CI) | ACMG/AMP strength | N (%) | N (%) |

| HGSC | 1578 (77.2) | 1.13 (1.10–1.16) | Non-informative | 597 (78.4) | 1.15 (1.10–1.19) | Non-informative | 5183 (68.5) | 7358 (70.9) |

| LGSC | 58 (2.8) | 0.50 (0.38–0.66) | Non-informative | 23 (3.0) | 0.53 (0.35–0.81) | Non-informative | 429 (5.7) | 510 (4.9) |

| Mucinous | 21 (1.0) | 0.24 (0.15–0.37) | Supporting Benign | 14 (1.8) | 0.43 (0.25–0.73) | Supporting Benign | 325 (4.3) | 360 (3.5) |

| Endometrioid | 226 (11.1) | 1.17 (1.02–1.35) | Non-informative | 65 (8.5) | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | Non-informative | 713 (9.4) | 1004 (9.7) |

| Clear cell | 38 (1.9) | 0.23 (0.17–0.32) | Supporting Benign | 15 (2.0) | 0.25 (0.15–0.41) | Supporting Benign | 605 (8.0) | 658 (6.3) |

| ‘Other’ | 123 (6.0) | 1.45 (1.19–1.78) | Non-informative | 47 (6.2) | 1.49 (1.11–2.01) | Non-informative | 313 (4.1) | 483 (4.7) |

| 2044 | 761 | 7568 | 10,373 | |||||

N number of data points, LR likelihood ratio, CI confidence interval, ACMG/AMP American College of Medical Genetics/Association for Molecular Pathology, HGSC high-grade serous carcinomas, LGSC low-grade serous carcinomas

The analysis was based on 10,373 cases, including 2044 BRCA1 carriers, 761 BRCA2 carriers and 7568 non-carriers. In brackets, the histotype frequency for each group is provided. The ‘other’ category denominates rare forms of ovarian cancer not belonging to any of the other subtypes, including tumours defined as: ‘other’ by data sources not specifying tumour histology; mixed-epithelial; carcinosarcomas; transitional cell (Brenner tumours); undifferentiated or poorly differentiated; squamous cell. LR > 1: Histotype association with pathogenic variant, Pathogenic evidence; LR < 1: Prediction of non-carrier for pathogenic variant, Benign evidence. Evidence strength was measured based on Bayesian modelling of ACMG/AMP rules (see 'Materials and methods'); Supporting Benign (LR ≥ 0.23–0.48), Moderate Benign (LR ≥ 0.053–0.23), Supporting Pathogenic (LR ≥ 2.08–4.30), non-informative (0.48 ≤ LR ≤ 2.08). LR estimates reaching informative ACMG/AMP strengths at a statistically significant CI (i.e., not spanning 1), are highlighted in bold.

Histological subtype associations also were compared between clinically derived and literature-derived data, to determine any major differences (Supplementary Table S4). Not all subtypes provided sufficient occurrences in this stratified dataset for informative comparisons. Overall, differences in ACMG/AMP code strength were observed for LGSC for BRCA1 and BRCA2 and mucinous for BRCA2, but these estimates, for literature-derived data in particular, were based on a small number of cases in each category, and confidence intervals for LR estimates overlapped.

Evaluation of the associations also were assessed by ancestry, by comparing the results of Asian- and European-ancestry data separately (Supplementary Table S5). Considering that the Asian-ancestry dataset was much smaller, no meaningful differences were observed in the direction of effect for LR estimates between the two sets, with the exception of the mucinous histotype which was not reported in Asian-origin BRCA1 carriers. Results of the European-origin data alone, agreed with the LR estimates derived in the main analysis, with the addition of LGSC providing evidence against BRCA1 variant pathogenicity (LR: 0.45 (95% CI: 0.33–0.60), supporting evidence).

Assessing combined ovarian tumour characteristics

Histology associations with BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity were further refined by performing the LR analyses in combination with other ovarian tumour characteristics. First, histological categories were refined by tumour grade (Supplementary Table S6). Refinement resulted in a small amount of data within some categories, for which estimates should be used with caution. Endometrioid tumours of well-differentiated grade provided evidence against VUS pathogenicity for BRCA1 (LR: 0.12 (95% CI: 0.04–0.31), moderate evidence) and BRCA2 (LR: 0.31 (95% CI: 0.12–0.84), supporting evidence). In contrast, poorly differentiated endometrioid tumours were associated with evidence in favour of BRCA1 variant pathogenicity (LR: 2.98 (95% CI: 2.28–3.89), supporting evidence) and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity (LR: 2.09 (95% CI: 1.37–3.21), supporting evidence). Finally, the ‘other’ category provided informative evidence towards variant pathogenicity for both BRCA1 (LR: 3.62 (95% CI: 2.61–5.03), supporting evidence) and BRCA2 (LR: 3.46 (95% CI: 2.20–5.43), supporting evidence), if tumours were undifferentiated or poorly differentiated. Histology was integrated with information on tumour invasion (invasive or borderline) (Supplementary Table S7). Here, borderline tumours, irrespective of histology, were associated with moderate ACMG/AMP evidence against variant pathogenicity for BRCA1 (LR: 0.09 (95% CI: 0.04–0.20)) and BRCA2 (LR: 0.19 (95% CI: 0.08–0.46)). When invasive histological subtypes were assessed, similar LR estimates were obtained as in the main analysis. In addition, evidence against pathogenicity increased from supporting to moderate strength for invasive mucinous and clear cell tumours for BRCA1, and for invasive clear cell tumours for BRCA2. Also, invasive LGSC was associated with evidence against BRCA1 pathogenicity at supporting strength (LR: 0.44 (95% CI: 0.31–0.62)). Histology-derived LRs also were estimated when categorised by age at ovarian cancer diagnosis (Supplementary Table S8). LGSC presentation before age 50 years provided evidence against pathogenicity for BRCA1 (LR: 0.18 (95% CI: 0.11–0.30), moderate strength). Mucinous tumour presentation provided somewhat greater evidence for the association against BRCA1 variant pathogenicity when the diagnosis was before age 50 years (LR: 0.11 (95% CI: 0.06–0.19), moderate evidence), compared to diagnosis at/after the age of 50 (LR: 0.21 (95% CI: 0.10–0.44), moderate evidence). Similarly, clear cell tumours provided somewhat greater evidence against BRCA1 variant pathogenicity before the age of 50 (LR: 0.16 (95% CI: 0.08–0.31), moderate evidence) versus over that age (LR: 0.37 (95% CI: 0.23–0.59), supporting evidence). For BRCA2, evidence against pathogenicity was reached for LGSC in individuals diagnosed before the age of 50 years (LR: 0.43 (95% CI: 0.19–0.96), supporting evidence). Mucinous tumours provided supporting evidence against BRCA2 variant pathogenicity in individuals diagnosed both before the age of 50 (LR: 0.36 (95% CI: 0.16–0.80), supporting evidence) and after the age of 50 (LR: 0.42 (95% CI: 0.21–0.87), supporting evidence). Likewise, clear cell tumour phenotype provided supporting evidence against pathogenicity at/after the age of 50 (LR: 0.30 (95% CI: 0.15–0.58)).

Based on the patient’s available information and based on which characteristic(s) were clinically informative in different sub-analyses, we propose that LR estimates and corresponding ACMG/AMP evidence are applied only for the characteristics presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Proposed application of ovarian cancer pathology characteristics for the interpretation of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants, using the ACMG/AMP system*.

| Tumour pathology | BRCA1 evidence | BRCA2 evidence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Additional characteristics (If applicable) | ACMG/AMP strength | LR (95% CI) | ACMG/AMP strength | LR (95% CI) | Source |

| LGSC | Age at diagnosis <50 y | Moderate benign | 0.18 (0.11–0.30) | Supporting Benign | 0.43 (0.19–0.96) | Supplementary Table S8 |

| Invasive, age unspecified | Supporting benign | 0.44 (0.31–0.62) | – | – | Supplementary Table S7 | |

| Mucinous | – | Supporting benign | 0.24 (0.15–0.37) | Supporting Benign | 0.43 (0.25–0.73) | Table 2 |

| Endometrioid | Grade 1 | Moderate benign | 0.12 (0.04–0.31) | Supporting Benign | 0.31 (0.12–0.84) | Supplementary Table S6 |

| Grade 3 | Supporting pathogenic | 2.98 (2.28–3.89) | Supporting Pathogenic | 2.09 (1.37–3.21) | Supplementary Table S6 | |

| Clear cell | – | Supporting benign | 0.23 (0.17–0.32) | Supporting Benign | 0.25 (0.15–0.41) | Table 2 |

| Borderline | – | Moderate benign | 0.09 (0.04–0.20) | Moderate Benign | 0.19 (0.08–0.46) | Supplementary Table S7 |

LR likelihood ratio, CI confidence interval, ACMG/AMP American College of Medical Genetics/Association for Molecular Pathology, LGSC low-grade serous carcinomas, y years.

Evidence strength was measured based on Bayesian modelling of ACMG/AMP rules (see 'Materials and methods').

*Only associations reaching informative ACMG/AMP strengths at a statistically significant CI (i.e., not spanning 1), of which the characteristics were clinically informative, are shown. All other tumour histotypes (irrespective of additional characteristics) are considered uninformative for variant interpretation.

Discussion

In this multicentre study, we evaluated the association of ovarian tumour histology with germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant status. We aimed to standardise the application of this evidence in clinical variant curation using the ACMG/AMP classification system, to inform future VUS interpretation in BRCA1 and BRCA2.

Following the alignment to the ACMG/AMP evidence strengths, no associations were derived in favour of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity for the ovarian cancer histotypes analysed (Table 2). Nominal associations in favour of pathogenicity for the HGSC histotype may be suitable for inclusion in Multifactorial Likelihood modelling. This weak evidence reflects the high percentage of HGSC in ovarian cancer, irrespective of the presence of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants [1]. Evidence against pathogenicity at supporting strength was derived for BRCA1 and BRCA2 for the mucinous and clear cell histologies. Furthermore, evidence against pathogenicity for some categories, even though they may not reach ACMG/AMP strengths, could be used for inclusion in Multifactorial Likelihood modelling.

Sensitivity analyses exploring the heterogeneity within the dataset indicated that the inclusion of clinically- or research-collected data and data from published sources was unlikely to have caused any major confounding within the dataset. No significant differences were observed when comparing associations between data of different ancestries. However, the small data sizes of non-European ancestry data did not allow for reliable predictions and may not be generalisable.

In addition, we performed a series of refined histological subgroup analyses with the aim of incorporating additional information in the ovarian cancer pathology component of variant interpretation. Briefly, clinically informative predictions were derived for the endometrioid histology when separated by grade. Well-differentiated endometrioid tumour subtype was associated with evidence against BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity. Undifferentiated or poorly differentiated endometrioid tumour subtypes were associated with evidence in favour of variant pathogenicity, which likely reflects a proportion of misclassified HGSCs [44]. Although we observed an association in favour of pathogenicity of the ‘other’ subtype category when combined with the grade, we do not recommend use in clinical practice due to the high possibility of data misclassification within this category (HGSC or undefined/unknown histology often miscalled as ‘other’ (12.7% of ‘other’ category are poorly differentiated/undifferentiated which are often miscalled as HGSC cases). The association of this category with BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity should be evaluated in future studies. Refined analyses also suggested that borderline phenotype (irrespective of histology) was associated with evidence against BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity at moderate strength. Therefore, despite the rare occurrence of mucinous or borderline characteristics in carriers of pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants, the phenotypes have a clinical value in informing VUS interpretation. Since the majority of data for borderline cases were of mucinous histology, the identification of such evidence is consistent with earlier observations for the histotype. Refinement by invasive designation also informed predictions against variant pathogenicity. Lastly, when age at diagnosis was considered, clinically informative predictions were identified for LGSC histotype diagnosis before the age of 50 years, providing evidence against BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant pathogenicity.

Based on the above results, we propose a strategy for the use of ovarian tumour histology in the assessment of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS interpretation under the strict rules of the ACMG/AMP system, based on patient characteristics and available information (Table 3). This information may be used in combination with other evidence to inform variant classification, and subsequent patient and family management. The identified LR estimates (Table 2) may also be used directly within the Multifactorial Likelihood model. Note that, optimally, ascertainment criterion for genetic testing of the carrier should be considered when applying LRs (e.g., testing for only HGSC). Our study also provides a demonstration on the use of statistical likelihood ratio modelling for the evaluation of associations of tumour characteristics and variant pathogenicity, with applicability to inform variant interpretation in other tumour types and genes.

We would like to acknowledge the following caveats. Although we tried to minimise the effect of potential selection for BRCA1 and BRCA2 clinical testing based on histological phenotype, we cannot discount the possibility of selection in individual sites. Studies applying selection for BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing based on non-mucinous histology were excluded from the main analysis [11, 17, 38–41]. A separate analysis including these data (an additional 159 BRCA1 carriers, 101 BRCA2 carriers and 982 non-carriers) did not materially change our predictions; findings suggest that the LRs from the main analysis will be applicable in the context of non-mucinous testing, although it should be noted that the additional data points per histological category were relatively few except for HGSC (data not shown). Finally, although the data collection requirements specified the inclusion of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant carriers, due to the absence of detailed variant information for data evaluation, and due to changes in classification practices over time, we cannot exclude the possibility that some variants might be misclassified. Furthermore, due to the wide confidence intervals for some of the subtype-specific results, a more conservative approach might be required before the use of these evidence categories in the clinical classification of variants. Overall, it is likely that the practical application of LRs for future variant interpretation will provide additional insight into their correlation with existing clinical and functional evidence types already commonly used in BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant interpretation.

Conclusion

In this study, ovarian cancer histological subtypes were evaluated as predictors of BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variant status. We also provided refined LR estimates for the association of ovarian cancer histology in combination with other tumour and patient characteristics. Overall, we provide evidence for the incorporation of the derived LR estimates in variant classification to improve the interpretation of VUS identified in the BRCA1 and BRCA2, and thereby inform carrier clinical management.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank all patients and their families for submitting their data and all the collaborators, researchers, clinicians, technicians and coordinating teams who have enabled this work to be carried out. We acknowledge the Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics (CING), the CING institution and the Telethon organisation Cyprus for supporting this work. We acknowledge the contribution of the CIMBA (https://cimba.ccge.medschl.cam.ac.uk/) and ENIGMA (https://enigmaconsortium.org/) consortium, members and collaborators. We also acknowledge the contributions of the OTTA consortium (https://ottaconsortium.org/) and the AOCS Group (http://www.aocstudy.org). AOCS gratefully acknowledges additional support from Ovarian Cancer Australia and the Peter MacCallum Cancer Foundation. CIMBA acknowledges: All the families and clinicians who contributed to the studies; Catherine M. Phelan for her contribution to CIMBA until she passed away on 22 September 2017; Sue Healey, in particular taking on the task of mutation classification with the late Olga Sinilnikova; clinicians, patients, researchers, technicians and nurses of A.C. Camargo Cancer Center for their contribution to this study; Oncogenetic Department, Clinical and Functional Genomics Group, Center of Genomic Diagnostics, Biobank and other International Research Center-CIPE’ facilities at AC. Camargo Cancer Center, especially Karina Miranda Santiago, Giovana Tardin Torrezan, José Claudio Casali, Nirvana Formiga and Fabiana Baroni Makdissi; Maggie Angelakos, Judi Maskiell, Gillian Dite, Helen Tsimiklis; members and participants in the New York site of the Breast Cancer Family Registry; members and participants in the Ontario Familial Breast Cancer Registry; Vilius Rudaitis and Laimonas Griškevičius; Drs Janis Eglitis, Anna Krilova and Aivars Stengrevics; Yuan Chun Ding and Linda Steele for their work in participant enrollment and biospecimen and data management; Bent Ejlertsen for the recruitment and genetic counselling of participants; Alicia Barroso, Rosario Alonso and Guillermo Pita; all the individuals and the researchers who took part in CONSIT TEAM (Consorzio Italiano Tumori Ereditari Alla Mammella), in particular: Dario Zimbalatti, Daniela Zaffaroni, Laura Ottini, Giuseppe Giannini, Laura Papi, Gabriele Lorenzo Capone, Maria Grazia Tibiletti, Daniela Furlan, Antonella Savarese, Aline Martayan, Stefania Tommasi, Brunella Pilato and the personnel of the Cogentech Cancer Genetic Test Laboratory, Milan, Italy. The FCCC cohort (Godwin) acknowledges Ms. JoEllen Weaver and Dr. Betsy Bove, and the KUMC cohort (Sharma and Godwin) acknowledge the support of Michele Park, Lauren DiMartino, Alex Webster and the current and past members of the Biospecimen Repository Core Facility (BRCF) at KUMC; all participants, clinicians, family doctors, researchers, and technicians for their contributions and commitment to the DKFZ study and the collaborating groups in Lahore, Pakistan (Muhammad U. Rashid, Noor Muhammad, Sidra Gull, Seerat Bajwa, Faiz Ali Khan, Humaira Naeemi, Saima Faisal, Asif Loya, Mohammed Aasim Yusuf) and Bogota, Colombia (Diana Torres, Ignacio Briceno, Fabian Gil). FPGMX: members of the Cancer Genetics group (IDIS): Marta Santamariña, Miguel E. Aguado-Barrera, Olivia Fuentes Ríos and Ana Crujeiras-González; the GIIS025 research nurses and staff for their contributions to this resource, and the many families who contribute to GIIS025; IFE - Leipzig Research Centre for Civilisation Diseases (Markus Loeffler, Joachim Thiery, Matthias Nüchter, Ronny Baber); Genetic Modifiers of Cancer Risk in BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers (GEMO) study is a study from the National Cancer Genetics Network UNICANCER Genetic Group, France. We wish to pay tribute to Olga M. Sinilnikova, who with Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet initiated and coordinated GEMO until she sadly passed away on the June 30, 2014. The team in Lyon (Olga Sinilnikova, Mélanie Léoné, Laure Barjhoux, Carole Verny-Pierre, Sylvie Mazoyer, Francesca Damiola, Valérie Sornin) managed the GEMO samples until the biological resource centre was transferred to Paris in December 2015 (Noura Mebirouk, Fabienne Lesueur, Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet). We want to thank all the GEMO collaborating groups for their contribution to this study: Coordinating Centre, Service de Génétique, Institut Curie, Paris, France: Muriel Belotti, Ophélie Bertrand, Anne-Marie Birot, Bruno Buecher, Sandrine Caputo, Chrystelle Colas, Emmanuelle Fourme, Marion Gauthier-Villars, Lisa Golmard, Marine Le Mentec, Virginie Moncoutier, Antoine de Pauw, Claire Saule, Dominique Stoppa-Lyonnet, and Inserm U900, Institut Curie, Paris, France: Fabienne Lesueur, Noura Mebirouk, Yue Jiao. Contributing Centres: Unité Mixte de Génétique Constitutionnelle des Cancers Fréquents, Hospices Civils de Lyon - Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France: Nadia Boutry-Kryza, Alain Calender, Sophie Giraud, Mélanie Léone. Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France: Brigitte Bressac-de-Paillerets, Odile Cabaret, Olivier Caron, Marine Guillaud-Bataille, Etienne Rouleau. Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont–Ferrand, France: Yves-Jean Bignon, Nancy Uhrhammer. Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France: Valérie Bonadona, Sophie Dussart, Christine Lasset, Pauline Rochefort. Centre François Baclesse, Caen, France: Pascaline Berthet, Laurent Castera, Dominique Vaur. Institut Paoli Calmettes, Marseille, France: Violaine Bourdon, Catherine Noguès, Tetsuro Noguchi, Cornel Popovici Audrey Remenieras, Hagay Sobol. CHU Arnaud-de-Villeneuve, Montpellier, France: Isabelle Coupier, Pascal Pujol. Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France: Claude Adenis, Aurélie Dumont, Françoise Révillion. Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg, France: Danièle Muller. Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, France: Emmanuelle Barouk-Simonet, Françoise Bonnet, Virginie Bubien, Anaïs Dupré, Anne Floquet, Michel Longy, Marie Louty, Cécile Maninna, Nicolas Sevenet, Institut Claudius Regaud, Toulouse, France: Laurence Gladieff, Rosine Guimbaud, Viviane Feillel, Christine Toulas. CHU Grenoble, France: Hélène Dreyfus, Dominique Leroux, Clémentine Legrand, Christine Rebischung. CHU Dijon, France: Amandine Baurand, Geoffrey Bertolone, Fanny Coron, Laurence Faivre, Caroline Jacquot, Sarab Lizard, Sophie Nambot. CHU St-Etienne, France: Caroline Kientz, Marine Lebrun, Fabienne Prieur. Hôtel Dieu Centre Hospitalier, Chambéry, France: Sandra Fert Ferrer. Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France: Véronique Mari. CHU Limoges, France: Laurence Vénat-Bouvet. CHU Nantes, France: Stéphane Bézieau, Capucine Delnatte. CHU Bretonneau, Tours and Centre Hospitalier de Bourges France: Isabelle Mortemousque. Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpétrière, Paris, France: Florence Coulet, Mathilde Warcoin. CHU Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy, France: Myriam Bronner, Johanna Sokolowska. CHU Besançon, France: Marie-Agnès Collonge-Rame. CHU Poitiers, Centre Hospitalier d’Angoulême and Centre Hospitalier de Niort, France: Stéphanie Chieze-Valero, Paul Gesta, Brigitte Gilbert-Dussardier. Centre Hospitalier de La Rochelle: Hakima Lallaoui. CHU Nîmes Carémeau, France: Jean Chiesa. CHI Poissy, France: Denise Molina-Gomes. CHU Angers, France: Olivier Ingster; CHU de Martinique, France: Odile Bera; Mickaelle Rose; Drs. Taru A. Muranen and Carl Blomqvist, RN Outi Malkavaara; The Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON) consists of the following Collaborating Centres: Netherlands Cancer Institute (coordinating center), Amsterdam, NL: M.K. Schmidt, F.B.L. Hogervorst, F.E. van Leeuwen, M.A. Adank, D.J. Stommel-Jenner, R. de Groot; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, NL: J.M. Collée, M.J. Hooning, I.A. Boere; I.R. Geurts-Giele; Leiden University Medical Center, NL: C.J. van Asperen, P. Devilee, R.B. van der Luijt, T.C.T.E.F. van Cronenburg; Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, NL: M.R. Wevers, A.R. Mensenkamp; University Medical Center Utrecht, NL: M.G.E.M. Ausems, M.J. Koudijs; Amsterdam UMC, NL: K. van Engelen, J.J.P. Gille; Maastricht University Medical Center, NL: E.B. Gómez García, M.J. Blok, M. de Boer; University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, NL: L.P.V. Berger, A.H. van der Hout, M.J.E. Mourits, G.H. de Bock; The Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL): S. Siesling, J. Verloop; The nationwide network and registry of histo- and cytopathology in The Netherlands (PALGA): Q.J.M Voorham; the study participants and the registration teams of IKNL and PALGA for part of the HEBON data collection; Hong Kong Sanatorium and Hospital; the Hungarian Breast and Ovarian Cancer Study Group members (Attila Patócs, János Papp, Anikó Bozsik, Timea Pócza, Henriett Butz, Zoltán Mátrai, Lajos Géczi, National Institute of Oncology, Budapest, Hungary) and the clinicians and patients for their contributions to this study; Fatemeh Yadegari, Shiva Zarinfam and Rezvan Esmaeili for their role in participant enrollment and biospecimen and data management; the study participants and registration teams of the Hereditary Cancer Genetics Group of the Valld’Hebron Institute of Oncolgy (VHIO) and the Clinical and Molecular Genetics Department of the University Hospital Vall d’Hebron (HVH), the Cellex Foundation for providing research facilities, and CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support; members and participants of the Inherited Cancer Registry (ICARE); the ICO Hereditary Cancer Program team led by Dr. Gabriel Capella; the ICO Hereditary Cancer Program team led by Dr. Gabriel Capella; Dr Martine Dumont for sample management and skilful assistance; Catarina Santos and Pedro Pinto; members of the Center of Molecular Diagnosis, Oncogenetics Department and Molecular Oncology Research Center of Barretos Cancer Hospital; Heather Thorne, Eveline Niedermayr, all the kConFab research nurses and staff, the heads and staff of the Family Cancer Clinics, and the Clinical Follow Up Study (which has received funding from the NHMRC, the National Breast Cancer Foundation, Cancer Australia, and the National Institute of Health (USA)) for their contributions to this resource, and the many families who contribute to kConFab; the KOBRA Study Group; all participants and the collaborators from RCGEB “Georgi D. Efremov”, MASA (Ivana Maleva Kostovska, Simona Jakovcevska, Sanja Kiprijanovska), University Clinic of Radiotherapy and Oncology (Snezhana Smichkoska, Emilija Lazarova, Marina Iljovska), Adzibadem-Sistina Hospital (Katerina Kubelka-Sabit, Dzengis Jasar, Mitko Karadjozov), and Re-Medika Hospital (Andrej Arsovski and Liljana Stojanovska) for their contributions and commitment to the MACBRCA study; Csilla Szabo (National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA); Lenka Foretova and Eva Machackova (Department of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, Masaryk Memorial Cancer Institute and MF MU, Brno, Czech Republic); Petra Kleiblova, Marketa Janatova, Jana Soukupova (Institute of Medical Biochemistry and Laboratory Diagnostics, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University and General University Hospital in Prague (VFN), Czechia), Petra Zemankova, Petr Nehasil (Institute of Pathological Physiology, 1st Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Czechia), Michal Vocka (Department of Oncology, General University Hospital in Prague (VFN), Czechia), Anne Lincoln, Lauren Jacobs; the participants in Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer Study and Breast Imaging Study for their selfless contributions to our research; the NICCC National Familial Cancer Consultation Service team led by Sara Dishon, the lab team led by Dr. Flavio Lejbkowicz, and the research field operations team led by Dr. Mila Pinchev; the staff of Genetic Health Service NZ and the families who have contributed; members and participants in the Ontario Cancer Genetics Network; Hayley Cassingham. Leigha Senter, Kevin Sweet, Julia Cooper, and Amber Aielts; research nurses and staff of Breast Unit, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hopsital, RSUIO and the many families who contribute to the CIMBA registry of RSUIO; Yip Cheng Har, Nur Aishah Mohd Taib, Phuah Sze Yee, Norhashimah Hassan and all the research nurses, research assistants and doctors involved in the MyBrCa Study for assistance in patient recruitment, data collection and sample preparation, Philip Iau, Sng Jen-Hwei and Sharifah Nor Akmal for contributing samples from the Singapore Breast Cancer Study and the HUKM-HKL Study respectively; the National Cancer Centre Singapore Cancer Genetics Service (NCCS) for patient recruitement; the Meirav Comprehensive breast cancer center team at the Sheba Medical Center; Christina Selkirk; Håkan Olsson, Helena Jernström, Karin Henriksson, Katja Harbst, Maria Soller, Ulf Kristoffersson; from Gothenburg Sahlgrenska University Hospital: Anna Öfverholm, Margareta Nordling, Per Karlsson, Zakaria Einbeigi; from Stockholm and Karolinska University Hospital: Anna von Wachenfeldt, Annelie Liljegren, Annika Lindblom, Brita Arver, Gisela Barbany Bustinza, Johanna Rantala; from Umeå University Hospital: Beatrice Melin, Christina Edwinsdotter Ardnor, Monica Emanuelsson; from Uppsala University: Hans Ehrencrona, Maritta Hellström Pigg, Richard Rosenquist; from Linköping University Hospital: Marie Stenmark-Askmalm, Sigrun Liedgren; Cecilia Zvocec, Qun Niu; Joyce Seldon and Lorna Kwan; Dr. Robert Nussbaum, Beth Crawford, Kate Loranger, Julie Mak, Nicola Stewart, Robin Lee, Amie Blanco and Peggy Conrad and Salina Chan; Simon Gayther and Patricia Harrington; Geoffrey Lindeman, Marion Harris, Joanne McKinley, Simone McInerny, and Ella Thompson for performing all DNA amplification. HEBCS thanks Drs. Kristiina Aittomäki, Carl Blomqvist and Taru A. Muranen and research nurses Irja Erkkilä and Outi Malkavaara. HJO acknowledges the oncologists Tjoung-Won Park-Simon and Peter Hillemanns at Hannover Medical School, Clemens Liebrich at the Gynecology Clinics Wolfsburg, Ingo Runnebaum at the Gynaecology Clinics at the University of Jena, and Peter Dall at the Gynecology Clinics at the University of Lüneburg for providing clinical data and medical records to this analysis, Peter Schürmann for technical assistance, and Dhanya Ramachandran for contributing to BRCA1 and BRCA2 VUS analyses. The contents of the published material are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of NHMRC.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: KM, ABS, DEG, SJR, MCS, ACA, JS, FF, ESdS, TD and YYT; supervision: KM; study analyses and data curation: DGO; writing original draft: DGO, KM and ABS; writing review and editing: all authors. Data contributors: MCS, EMJ, UH, ENI, ILA, PSh, MBD, CRH, JNW, AJak, AKG, AAr, ABan, JSi, PSo, MAC, PLM, KBMC, MRT, WKC, CLaz, PJH, AET, ISP, FBLH, MAR, PD, SLN, AVe, MDLH, HNe, MD, LV, PAJ, RJ, LN-Z, FCN, TVOH, ABo, JRan, KOf, MMon, GC-T, KLN, SMD, AOs, MJG, BYK, FLes, AOCS, LMc, GLe, MTP, TD, PRa, LPap, CEn, EHah, RKS, BWa, DFE, MTi, CFS, YYT, AlSWhit, WSi, JDB, DY, FF, IKon, JS, PDPP, ACA, DEG and LS.

Funding

Denise G O’Mahony is supported by Telethon Cyprus (Telethon Cyprus: 33173233) through the Cyprus Institute of Neurology and Genetics. CIMBA: The CIMBA data management and data analysis were supported by Cancer Research—UK grants PPRPGM-Nov20\100002 and C12292/A20861 and the Gray Foundation. ABS and SJR are supported by the NHMRC Investigator Fellowships (APP177524 and APP2009840). iCOGS: the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement no. 223175 (HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (COGS), Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118, C1287/A 10710, C12292/A11174, C1281/A12014, C5047/A8384, C5047/A15007, C5047/A10692, C8197/A16565), the National Institutes of Health (CA128978) and Post-Cancer GWAS initiative (1U19 CA148537, 1U19 CA148065 and 1U19 CA148112—the GAME-ON initiative), the Department of Defence (W81XWH-10-1-0341), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for the CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer (CRN-87521), and the Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade (PSR-SIIRI-701), Komen Foundation for the Cure, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund. OncoArray: the PERSPECTIVE and PERSPECTIVE I&I projects funded by the Government of Canada through Genome Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the ‘Ministère de l’Économie, de la Science et de l’Innovation du Québec’ through Genome Québec, and the Quebec Breast Cancer Foundation; the NCI Genetic Associations and Mechanisms in Oncology (GAME-ON) initiative and Discovery, Biology and Risk of Inherited Variants in Breast Cancer (DRIVE) project (NIH Grants U19 CA148065 and X01HG007492); and Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118 and C1287/A16563). AOCS was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (DAMD17-01-1-0729), The Cancer Council Victoria, Queensland Cancer Fund, The Cancer Council New South Wales, The Cancer Council South Australia, The Cancer Council Tasmania, The Cancer Foundation of Western Australia, and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC; ID199600, ID400413, ID400281). For the BCFR-NY, BCFR-PA this work was supported by grant UM1 CA164920 from the National Cancer Institute. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centres in the Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organisations imply endorsement by the US Government or the BCFR. BFBOCC: Lithuania (BFBOCC-LT): Research Council of Lithuania grant P-MIP-22-187. BRICOH: SLN was partially supported by the Morris and Horowitz Families Endowed Professorship. CNIO: CNIO study is partially funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III, project reference PI19/00640, cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), “A way to make Europe” and the Spanish Network on Rare Diseases (CIBERER). CCGCRN: Research reported in this publication was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (project 20-172), National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant number R25CA112486, and RC4CA153828 (PI: J. Weitzel) from the National Cancer Institute and the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. CONSIT TEAM: Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; IG2015 no.16732) to P. Peterlongo. CZECANCA: projects of the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (NU20-03-00016; RVO-VFN64165), Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports of the Czech Republic (LX22NPO5102) and Charles University project COOPERATIO. DEMOKRITOS: European Union (European Social Fund—ESF) and Greek national funds through the Operational Program “Education and Lifelong Learning” of the National Strategic Reference Framework (NSRF) - Research Funding Program of the General Secretariat for Research & Technology: SYN11_10_19 NBCA. Investing in knowledge society through the European Social Fund. DFKZ: German Cancer Research Center. EMBRACE: Cancer Research UK Grants PRCPJT-Nov21\100004, C1287/A23382 and C1287/A26886. D Gareth Evans and Fiona Lalloo are supported by an NIHR grant to the Biomedical Research Centre, Manchester. The Investigators at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust are supported by an NIHR grant to the Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. Ros Eeles and Elizabeth Bancroft are supported by Cancer Research UK Grant C5047/A8385. Ros Eeles is also supported by NIHR support to the Biomedical Research Centre at The Institute of Cancer Research and The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. The FCCC and KUMC cohorts: The University of Kansas Cancer Center (P30 CA168524), the Kansas Institute for Precision Medicine (P20GM130423) and the Kansas Bioscience Authority Eminent Scholar Program. AKG was funded by R01CA140323, R01CA214545, R01CA260132, 5U10CA180888, and by the Chancellors Distinguished Chair in Biomedical Sciences Professorship. FPGMX: A.Vega is supported by the Spanish Health Research Foundation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), partially supported by FEDER funds through Research Activity Intensification Program (contract grant numbers: INT15/00070, INT16/00154, INT17/00133, INT20/00071), and through Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enferemdades Raras CIBERER (ACCI 2016: ER17P1AC7112/2018); Autonomous Government of Galicia (Consolidation and structuring program: IN607B), and by the Fundación Mutua Madrileña and Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC). GC-HBOC: German Cancer Aid (grant no 110837 and 113049, Rita K. Schmutzler), Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany (grant no 01GY1901), and the European Regional Development Fund and Free State of Saxony, Germany (LIFE - Leipzig Research Centre for Civilisation Diseases, project numbers 713-241202, 713-241202, 14505/2470, 14575/2470). GEMO, a study from the National Cancer Genetics Network UNICANCER Genetic Group, France.: Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer; the Association “Le cancer du sein, parlons-en!” Award, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for the “CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer” program, the Fondation ARC pour la recherche sur le cancer (grant PJA 20151203365) and the French National Institute of Cancer (INCa grants AOR 01 082, 2001-2003, 2013-1-BCB-01-ICH-1 and SHS-E-SP 18-015). HCSC: Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, ISCIII (Hayley) cofunded by FEDER Regional Development European Funds (EU). HEBCS: Helsinki University Hospital Research Fund, the Finnish Cancer Society and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation. The Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Research Group Netherlands (HEBON) consists of the following Collaborating Centers: Netherlands Cancer Institute; Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam; Leiden University Medical Center; Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center; University Medical Center Utrecht; Amsterdam UMC, Univ of Amsterdam; Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; Maastricht University Medical Center; University of Groningen. The HEBON study is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society grants NKI1998-1854, NKI2004-3088, NKI2007-3756, the Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research grant NWO 91109024, the Pink Ribbon grants 110005 and 2014-187.WO76, the BBMRI grant NWO 184.021.007/CP46 and the Transcan grant JTC 2012 Cancer 12-054. HJO: Ovarian cancer sequencing studies at Hannover Medical School were supported by the German Research Foundation (Do761/15-1). ICO: The authors would like to particularly acknowledge the support of the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer (AECC), the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (organismo adscrito al Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad) and “Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), una manera de hacer Europa” (PI10/01422, PI13/00285, PIE13/00022, PI15/00854, PI16/00563 and CIBERONC) and the Institut Català de la Salut and Autonomous Government of Catalonia (2009SGR290, 2014SGR338 and PERIS Project MedPerCan). IHCC: PBZ_KBN_122/P05/2004 and the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education under the name “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in 2019–2022 project number 002/RID /2018/19 amount of financing12 000 000 PLN. INHERIT: Canadian Institutes of Health Research for the “CIHR Team in Familial Risks of Breast Cancer” program – grant # CRN-87521 and the Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade – grant # PSR-SIIRI-701. IOVHBOCS: Ministero della Salute and “5×1000” Istituto Oncologico Veneto grant. IPOBCS: Liga Portuguesa Contra o Cancro. kConFab: The National Breast Cancer Foundation, and previously by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Queensland Cancer Fund, the Cancer Councils of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the Cancer Foundation of Western Australia. MSKCC: the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Robert and Kate Niehaus Clinical Cancer Genetics Initiative, the Andrew Sabin Research Fund and a Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748). NNPIO: Russian Science Foundation (grant 21-75-30015). NRG Oncology: U10 CA180868, NRG SDMC grant U10 CA180822, NRG Administrative Office and the NRG Tissue Bank (CA 27469), the NRG Statistical and Data Center (CA 37517) and the Intramural Research Program, NCI. OSUCCG: Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. SWE-BRCA: the Swedish Cancer Society. UCSF: UCSF Cancer Risk Program and Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. UKFOCR: Cancer Research UK. UPENN: Breast Cancer Research Foundation; Susan G. Komen Foundation for the cure, Basser Research Center for BRCA, NCI P30 CA016520. UPITT/MWH: Hackers for Hope Pittsburgh. VFCTG: Victorian Cancer Agency, Cancer Australia, National Breast Cancer Foundation. WCP: Dr Karlan is funded by the American Cancer Society Early Detection Professorship (SIOP-06-258-01-COUN) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), Grant UL1TR000124. T.D. was funded by the German Research Foundation (Do761/15-1). MT (Marc Tischkowitz) was supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC-1215-20014).

Data availability

All data generated in this study can be found in the Supplementary Material file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the Cyprus National Bioethics Committee (EEBK EΠ 2020.01.224). All clinically- and research-collected data were based on samples recruited by the host institutions under protocols approved by local ethics review boards at each participating institution and study group, consent form was obtained for each study participant. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lists of authors and their affiliations appear at the end of the paper.

Contributor Information

Kyriaki Michailidou, Email: kyriakimi@cing.ac.cy.

HEBON Investigators:

GEMO Study Collaborators:

AOCS Group:

The Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2:

Miguel de la Hoya, Thomas van Overeem Hansen, and Elizabeth Santana dos Santos

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-023-02263-5.

References

- 1.Sankaranarayanan R, Ferlay J. Worldwide burden of gynaecological cancer: the size of the problem. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20:207–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman JD, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Haiba M, Boice CR, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM. The histologic type and stage distribution of ovarian carcinomas of surface epithelial origin. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:41–4. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000101080.35393.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH (eds). WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs, 4th edn. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014.

- 4.Shih IeM, Kurman RJ. Ovarian tumorigenesis: a proposed model based on morphological and molecular genetic analysis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1511–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63708-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Boyd N, McKinney S, Mehl E, Palmer C, et al. Ovarian carcinoma subtypes are different diseases: implications for biomarker studies. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case Series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–30. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramus SJ, Song H, Dicks E, Tyrer JP, Rosenthal AN, Intermaggio MP, et al. Germline mutations in the BRIP1, BARD1, PALB2, and NBN genes in women with ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv214. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song H, Dicks E, Ramus SJ, Tyrer JP, Intermaggio MP, Hayward J, et al. Contribution of germline mutations in the RAD51B, RAD51C, and RAD51D genes to ovarian cancer in the population. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2901–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilyquist J, LaDuca H, Polley E, Davis BT, Shimelis H, Hu C, et al. Frequency of mutations in a large series of clinically ascertained ovarian cancer cases tested on multi-gene panels compared to reference controls. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147:375–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakhani SR, Manek S, Penault-Llorca F, Flanagan A, Arnout L, Merrett S, et al. Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2473–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrader KA, Hurlburt J, Kalloger SE, Hansford S, Young S, Huntsman DG, et al. Germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in ovarian cancer: utility of a histology-based referral strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:235–40. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825f3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malander S, Ridderheim M, Måsbäck A, Loman N, Kristoffersson U, Olsson H, et al. One in 10 ovarian cancer patients carry germ line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations: results of a prospective study in Southern Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:422–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biglia N, Sgandurra P, Bounous VE, Maggiorotto F, Piva E, Pivetta E, et al. Ovarian cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation carriers: analysis of prognostic factors and survival. Ecancermedicalscience. 2016;10:639. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2016.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song H, Cicek MS, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, Cunningham JM, et al. The contribution of deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes to ovarian cancer in the population. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4703–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SI, Lee M, Kim HS, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, et al. Germline and somatic BRCA1/2 gene mutational status and clinical outcomes in epithelial peritoneal, ovarian, and fallopian tube cancer: over a decade of experience in a single institution in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52:1229–41. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soegaard M, Kjaer SK, Cox M, Wozniak E, Høgdall E, Høgdall C, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation prevalence and clinical characteristics of a population-based series of ovarian cancer cases from Denmark. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3761–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauke J, Hahnen E, Schneider S, Reuss A, Richters L, Kommoss S, et al. Deleterious somatic variants in 473 consecutive individuals with ovarian cancer: results of the observational AGO-TR1 study ( NCT02222883) J Med Genet. 2019;56:574–80. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norquist BM, Harrell MI, Brady MF, Walsh T, Lee MK, Gulsuner S, et al. Inherited mutations in women with ovarian carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:482–90. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, Krischer JP, Fiorica J, Arango H, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, Buys SS, Dickson P, Domchek SM, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:77–102. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinopoulos PA, Norquist B, Lacchetti C, Armstrong D, Grisham RN, Goodfellow PJ, et al. Germline and somatic tumor testing in epithelial ovarian cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1222–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arts-de Jong M, de Bock GH, van Asperen CJ, Mourits MJ, de Hullu JA, Kets CM. Germline BRCA1/2 mutation testing is indicated in every patient with epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;61:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marth C, Hubalek M, Petru E, Polterauer S, Reinthaller A, Schauer C, et al. AGO Austria recommendations for genetic testing of patients with ovarian cancer. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2015;127:652–4. doi: 10.1007/s00508-015-0814-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panchal SM, Ennis M, Canon S, Bordeleau LJ. Selecting a BRCA risk assessment model for use in a familial cancer clinic. BMC Med Genet. 2008;9:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray ML, Cerrato F, Bennett RL, Jarvik GP. Follow-up of carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants of unknown significance: variant reclassification and surgical decisions. Genet Med. 2011;13:998–1005. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318226fc15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vos J, Otten W, van Asperen C, Jansen A, Menko F, Tibben A. The counsellees’ view of an unclassified variant in BRCA1/2: recall, interpretation, and impact on life. Psychooncology. 2008;17:822–30. doi: 10.1002/pon.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richter S, Haroun I, Graham TC, Eisen A, Kiss A, Warner E. Variants of unknown significance in BRCA testing: impact on risk perception, worry, prevention and counseling. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:viii69–viii74. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moghadasi S, Eccles DM, Devilee P, Vreeswijk MP, van Asperen CJ. Classification and clinical management of variants of uncertain significance in high penetrance cancer predisposition genes. Hum Mutat. 2016;37:331–6. doi: 10.1002/humu.22956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eccles DM, Mitchell G, Monteiro AN, Schmutzler R, Couch FJ, Spurdle AB, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic testing-pitfalls and recommendations for managing variants of uncertain clinical significance. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2057–65. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards CS, Bale S, Bellissimo DB, Das S, Grody WW, Hegde MR, et al. ACMG recommendations for standards for interpretation and reporting of sequence variations: revisions 2007. Genet Med. 2008;10:294–300. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31816b5cae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tavtigian SV, Greenblatt MS, Harrison SM, Nussbaum RL, Prabhu SA, Boucher KM, et al. Modeling the ACMG/AMP variant classification guidelines as a Bayesian classification framework. Genet Med. 2018;20:1054–60. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:535–44. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spurdle AB, Healey S, Devereau A, Hogervorst FB, Monteiro AN, Nathanson KL, et al. ENIGMA–evidence-based network for the interpretation of germline mutant alleles: an international initiative to evaluate risk and clinical significance associated with sequence variation in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:2–7. doi: 10.1002/humu.21628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindor NM, Guidugli L, Wang X, Vallée MP, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian S, et al. A review of a multifactorial probability-based model for classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants of uncertain significance (VUS) Hum Mutat. 2012;33:8–21. doi: 10.1002/humu.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lovelock PK, Spurdle AB, Mok MT, Farrugia DJ, Lakhani SR, Healey S, et al. Identification of BRCA1 missense substitutions that confer partial functional activity: potential moderate risk variants? Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R82. doi: 10.1186/bcr1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köbel M, Kalloger SE, Lee S, Duggan MA, Kelemen LE, Prentice L, et al. Biomarker-based ovarian carcinoma typing: a histologic investigation in the ovarian tumor tissue analysis consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1677–86. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, deFazio A, Emmanuel C, George J, et al. BRCA mutation frequency and patterns of treatment response in BRCA mutation-positive women with ovarian cancer: a report from the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berchuck A, Heron KA, Carney ME, Lancaster JM, Fraser EG, Vinson VL, et al. Frequency of germline and somatic BRCA1 mutations in ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2433–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choi MC, Heo JH, Jang JH, Jung SG, Park H, Joo WD, et al. Germline mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Korean ovarian cancer patients: finding founder mutations. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1386–91. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rust K, Spiliopoulou P, Tang CY, Bell C, Stirling D, Phang T, et al. Routine germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in patients with ovarian carcinoma: analysis of the Scottish real-life experience. BJOG. 2018;125:1451–8. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koopman PAR. Confidence intervals for the ratio of two binomial proportions. Biometrics. 1984;40:513–7. doi: 10.2307/2531405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vang R, Shih IeM, Kurman RJ. Ovarian low-grade and high-grade serous carcinoma: pathogenesis, clinicopathologic and molecular biologic features, and diagnostic problems. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:267–82. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181b4fffa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim D, Murali R, Murray MP, Veras E, Park KJ, Soslow RA. Morphological and immunohistochemical reevaluation of tumors initially diagnosed as ovarian endometrioid carcinoma with emphasis on high-grade tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:302–12. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated in this study can be found in the Supplementary Material file.