Summary

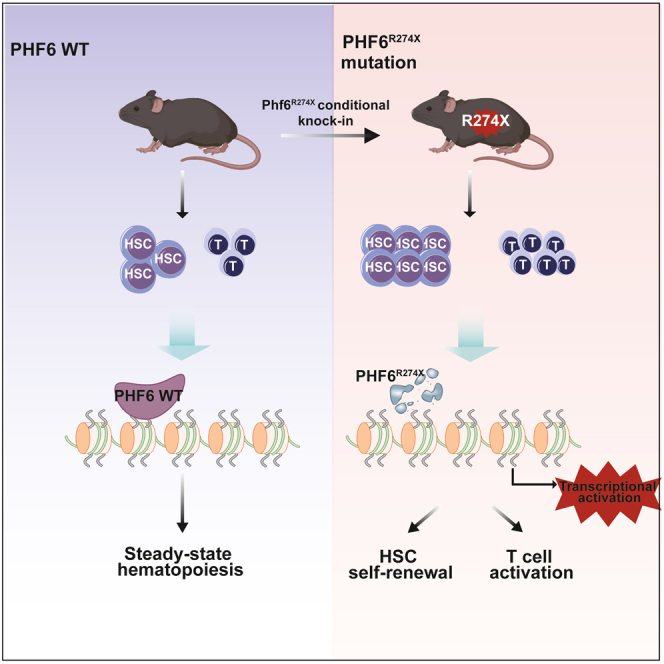

The PHD finger protein 6 (PHF6) mutations frequently occurred in hematopoietic malignancies. Although the R274X mutation in PHF6 (PHF6R274X) is one of the most common mutations identified in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients, the specific role of PHF6R274X in hematopoiesis remains unexplored. Here, we engineered a knock-in mouse line with conditional expression of Phf6R274X-mutated protein in the hematopoietic system (Phf6R274X mouse). The Phf6R274X mice displayed an enlargement of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) compartment and increased proportion of T cells in bone marrow. More Phf6R274X T cells were in activated status than control. Moreover, Phf6R274X mutation led to enhanced self-renewal and biased T cells differentiation of HSCs as assessed by competitive transplantation assays. RNA-sequencing analysis confirmed that Phf6R274X mutation altered the expression of key genes involved in HSC self-renewal and T cell activation. Our study demonstrated that Phf6R274X plays a critical role in fine-tuning T cells and HSC homeostasis.

Subject areas: Components of the immune system, Model organism, Molecular Genetics, Stem cells research

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We engineered a conditional Phf6R274X knock-in mouse line in hematopoietic system

-

•

Phf6R274X mutation expanded HSC/HPC pool in vivo

-

•

Phf6R274X mutation activated the proliferation and function of T cells in vivo

Introduction

The PHD finger protein 6 (PHF6), a member of PHD family, is an X-linked gene encodes a 365-amino acid protein and is highly conserved in vertebrate species.1 Structurally, PHF6 possesses two extended atypical PHD-like zinc fingers (ePHD) with a proposed role in gene transcription regulation.2,3 Intriguingly, unlike other PHD domain-containing proteins, PHF6-ePHD is not able to interact with histones. It’s found that PHF6-ePHD2 could bind dsDNA.2 Nevertheless, it is possible that the ePHD2 domain could interact with RNA, given the role of PHF6 in regulating rRNA synthesis.4 Moreover, structural analysis of PHF6-ePHD2 showed that mutations in ePHD2 could change the folding of the ePHD2 domain and affect the function of PHF6, possible leading to pathological consequences as suggested in Borjeson-Forssman-Lehmann syndrome (BFLS), T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), and Acute myeloid leukemia (AML).2

PHF6 was expressed in almost all tissues. Notably, it was high expressed in CD34+ precursor cells and B cells.5 Several mouse models with Phf6 conditional knockout in hematopoietic system showed that loss of Phf6 enhanced hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal capacity.6,7,8 Interestingly, Phf6 deficiency alone in hematopoietic system was insufficient for leukemia initiation without additional driver gene mutations.8,9,10 Somatic mutations of PHF6 have been observed in a variety of hematopoietic malignancies. Studies revealed that the inhibition of PHF6 expression suppressed the growth of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) cells, while enhanced the tumor progression of T-ALL.11 These findings indicated that PHF6 may have oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions in a context-dependent manner. The mutation type of PHF6 in hematopoietic malignancies includes deletion, frameshift, nonsense, and missense mutations, and interestingly, with more mutations concentrated in the ePHD2 domain.12,13,14 The point mutation c.820C > T (p.R274X), which lead to the truncation of the last 92 amino acids of PHF6, located on ePHD2 domain and frequently occurred in leukemia patients.14,15 However, the role of PHF6R274X in hematopoiesis remain unknown.

In this study, we generated a Vav1 promoter-driven Phf6R274X knock-in mouse model (Phf6R274X mouse) to elucidate the function of Phf6R274X in hematopoiesis in vivo. We found that Phf6R274X affected self-renewal ability of HSCs and T cells proliferation and activation. Our findings provided a study model for human blood diseases with PHF6R274X and gave a novel insight into the role of PHF6R274X mutation in hematopoietic homeostasis.

Results

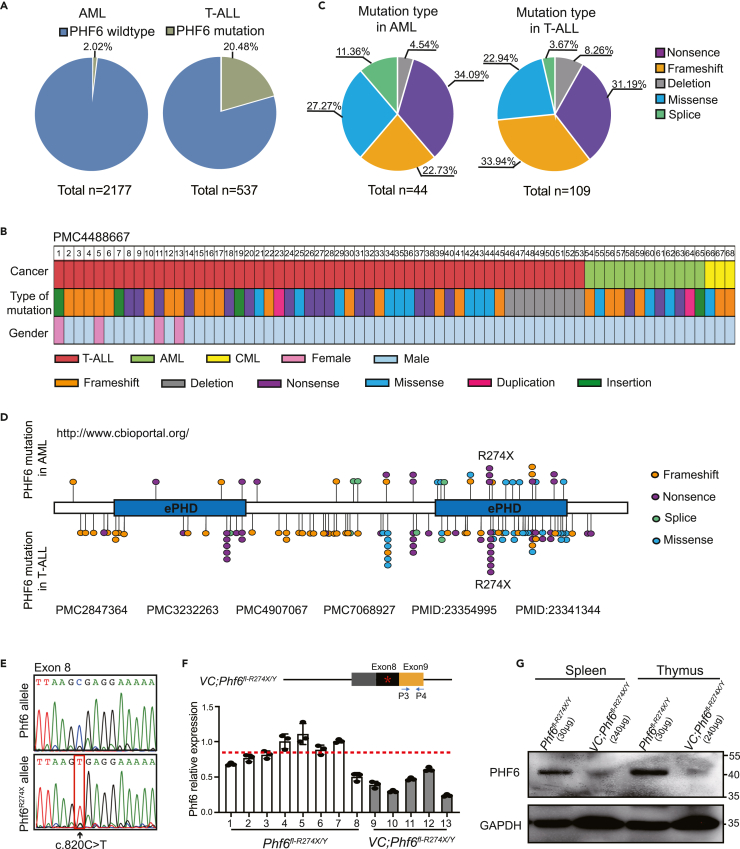

PHF6R274X mutation frequently occurred in AML and T-ALL patients

To investigate the role of PHF6 in leukemia patients, we analyzed PHF6 mutations in the genetic data of 2177 AML (http://www.cbioportal.org) and 537 T-ALL cases12,16,17,18,19 from different clinical centers. Consistent with previous studies,12,13 PHF6 mutations occurred in 2.02% (44/2177) of AML patients and 20.48% (110/537) of T-ALL patients (Figure 1A). Notably, we found that most PHF6 alterations presented in T-ALLs, AMLs, and chronic myeloid leukemias (CMLs) were nonsense, frameshift, and deletion mutations (Figure 1B), which accounted for more than half of all PHF6 mutations identified in T-ALL and AML samples (Figure 1C). In addition, we further analyzed details of PHF6 mutations in 44 AML and 109 T-ALL samples. We found that the R274X occurred in 9.68% (3/31) of AML patients with PHF6 mutations and in 7.09% (7/99) of T-ALL patients with PHF6 mutations, indicating that PHF6R274X mutation was most frequent in T-ALL and AML patients (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

PHF6R274X is one of the most common mutations in AML and T-ALL patients

(A) Differential distribution of PHF6 mutations in AML and T-ALL samples. Left panel, the frequency of PHF6 mutations (green) in AML patients. Right panel, the frequency of PHF6 mutations (green) in T-ALL patients.

(B) The mutation types of PHF6 found in 68 leukemia patients in PMC4488667 from Todd, M. A. et al.20 Each type of mutation is indicated by a unique color.

(C) Nonsense, frameshift, missense, deletion, and splicing variations of PHF6 in AML and T-ALL patients. Left panel, mutation type of PHF6 in AML patients. Right panel, mutation type of PHF6 in T-ALL patients.

(D) Schematic representation of the functional domains and locations of mutations in the human PHF6 protein. Two atypical plant homeodomain (PHD) zinc-finger domains are shown in blue. Each mutation site is indicated by a filled circle with unique color. Mutations in AML samples are shown above the bar, while mutations in T-ALL samples are shown under the bar.

(E) Sequencing analysis of cDNA isolated from BM cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice.

(F) RT-PCR showing the mRNA expression of wild-type Phf6 or mutant Phf6R274X using primer set P3 and P4 after Phf6R274X mutation.

(G) Western blotting analysis of Phf6R274X expression or wild-type PHF6 expression in spleen and thymus cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. Data information: in (F) data are shown as the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

To investigate the biological role of PHF6R274X mutation in hematopoiesis, we engineered a knock-in mouse line with conditional expression of this mutation in the endogenous Phf6 locus (Phf6fl-R274X/fl-R274X or Phf6fl-R274X/Y). To induce the expression of Phf6R274X in hematopoietic system, we crossed Phf6fl-R274X/Y knock-in mice with the Vav1-Cre transgenic mice, which expressed Cre specifically in blood cells (Figure S1A and S1B). The genotype and sequencing analysis confirmed the engineered C to T transition at exon 8 (c.820C > T) of the Phf6 gene (Figure S1C and 1E) in bone marrow (BM) cells of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Phf6R274X mice). Interestingly, although the Phf6R274X mRNA expression in BM cells of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice was approximately 40%–60% of Phf6 in Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Figure 1F), the expression of Phf6R274X protein was greatly reduced in spleen and thymus cells of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Figure 1G). We further sorted Lin− cells from the bone marrow (BM) of Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice, and found that the protein of PHF6R274X was greatly reduced in Lin− cells (Figure S1D). These data indicated that the Phf6R274X-mutation containing gene could successfully transcript to mRNA, while the protein translation of Phf6R274X was compromised in hematopoietic cells.

Phf6R274X mutation increases hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSC/HPC) pool in Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice

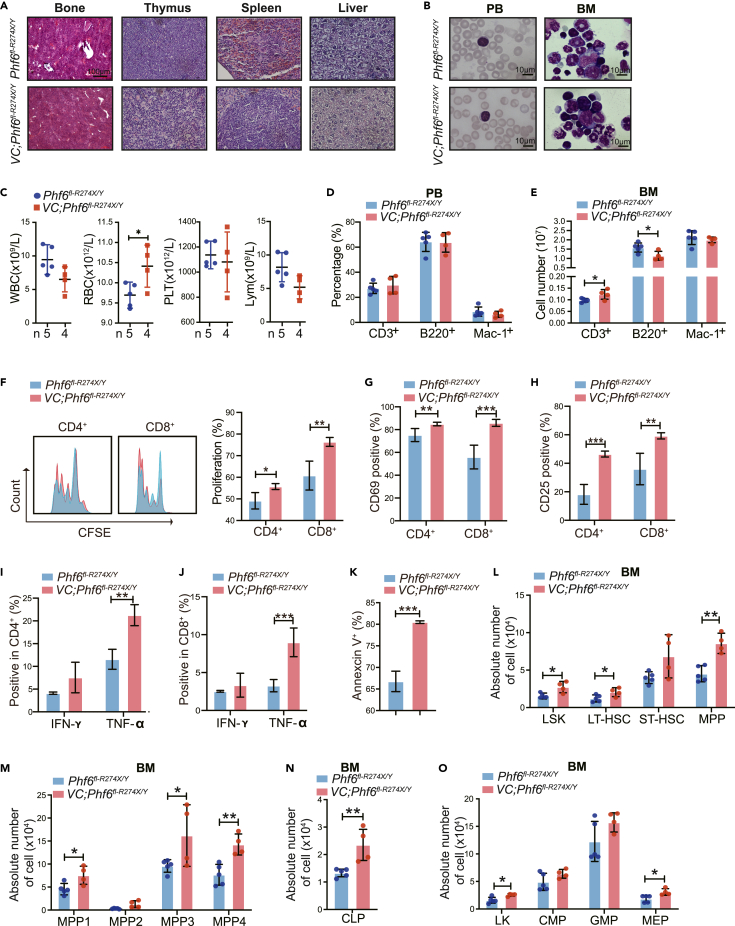

To investigate the impact of Phf6R274X mutation in hematopoiesis, we compared hematopoietic parameters of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice with their littermate controls. The histologic sections showed no dysplasia in Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Figure 2A). The weight of thymus and spleen was similar in Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice and Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice, respectively (Figure S2A-B). No obvious abnormality was observed in peripheral blood (PB) and BM cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice stained with Wright-Giemsa staining (Figure 2B). While Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice had slightly higher red blood cell (RBC) counts in PB (Figure 2C). Flow cytometric analysis showed that the proportion of T, B, and myeloid cells in PB was equivalent in Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Figure 2D). The percentage of T cells was slightly increased in spleen of Phf6R274X mice (Figure S2C), while the percentage of T cells in thymus was similar between the two groups (Figure S2D). Notably, the absolute number of T cells in BM was increased (Figure 2E). Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CSFE) analysis revealed that Phf6R274X increased proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2F). CD69 and CD25 were T cell activation markers.21 We found the expression of CD69 and CD25 was significantly increased in Phf6R274X T cells as compared to controls (Figures 2G and 2H). Furthermore, Phf6R274X increased the expression of TNF-α, while it did not alter IFN-γ production in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2IJ). It suggested that Phf6R274X might promote the proliferation and activation of T cells. We, thus, further examined the role of Phf6R274X in T cell functioning by measuring T cell-mediated killing after CD3+ T cells were co-cultured with primary spleen cells from MLL-AF9-induced AML mouse model for 12 h. We found that Phf6R274X mutation increased the killing abilities of T cells (Figure 2K). These results demonstrated that Phf6R274X mutation might affect the function of T cells.

Figure 2.

Phf6R274X mutation increases the proliferation of hematopoietic stem cells

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of BM, spleen, thymus, and liver.

(B) Wright-Giemsa staining of PB smears and BM cytospin.

(C) White blood cell (WBC), red blood cell (RBC), platelet (PLT), and lymphocyte (Lym) counts in PB by routine blood tests from Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 5) and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 4).

(D) FACS analysis of the percentage of T, B and myeloid cells in PB and BM from Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 5) and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 4) mice.

(E) The absolute number of T, B, and myeloid cells in BM from Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 5) and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 4) mice.

(F) Primary T cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice were treated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 24 h. The proliferation index of CD4+ and CD8+ cells were measured by CFSE-staining analysis (n = 4).

(G and H) Primary T cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice were treated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 4). (G) Stimulated for 12h and expression of CD69 on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. (H) Stimulated for 72 h and expression of CD25 on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(I and J) After primary T cells were treated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 24 h, cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of PMA, ionomycin, and Golgiplug for 6h. Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion by (I) CD4+ cell; (J) CD8+ cell (n = 3).

(K) Primary T cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice-mediated killing assay in primary spleen cells from MAL-AF9 mice, measured by Annexin V staining (n = 3).

(L–O) The absolute number of LSK (Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+) cells, LT-HSC (Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+CD34–Flt3low), ST-HSC (Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+CD34+Flt3low), MPP (Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+CD34+Flt3+), MPP1 (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD135−CD150−CD48−), MPP2 (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD135−CD150+CD48+), MPP3 (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD135−CD150−CD48+), MPP4 (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD135+CD150−CD48+), LK (Lin–Sca1−c-Kit+) cells, CMP (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD34+CD16/32low), GMP (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD34+CD16/32high) and MEP (Lin–c-Kit+Sca1–CD34–CD16/32low) populations, and CLP (Lin–IL-7r+Sca1+c-Kit+) in BM from Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 5) and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y (n = 4) mice. Data information: All mice used here were male mice of 8–10 weeks of age. In (C–O) data are shown as the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

We further investigated the role of Phf6R274X mutation in HSC/HPCs in vivo. We found that absolute number of LSK (Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+) cells, long term-HSCs (LT-HSCs), and Multipotent blood progenitors (MPP) was higher in the BM of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice than that of controls (Figure 2L). The cell count of MPP1, MPP3, and MPP4 was also increased in the BM of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice (Figure 2M). The absolute number of common lymphoid progenitor (CLP), LK (Lin–Sca-1−c-Kit+), and megakaryocyte–erythroid progenitor cell (MEP) was increased in the BM of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice as compared with controls (Figures 2N and 2O). In addition, the percentage of LSK cells and LK cells were equivalent in spleen of Phf6R274X mice and the control mice (Figure S2E and S2F). Collectively, these data indicated that Phf6R274X mutation increased the HSC/HPC pool in vivo.

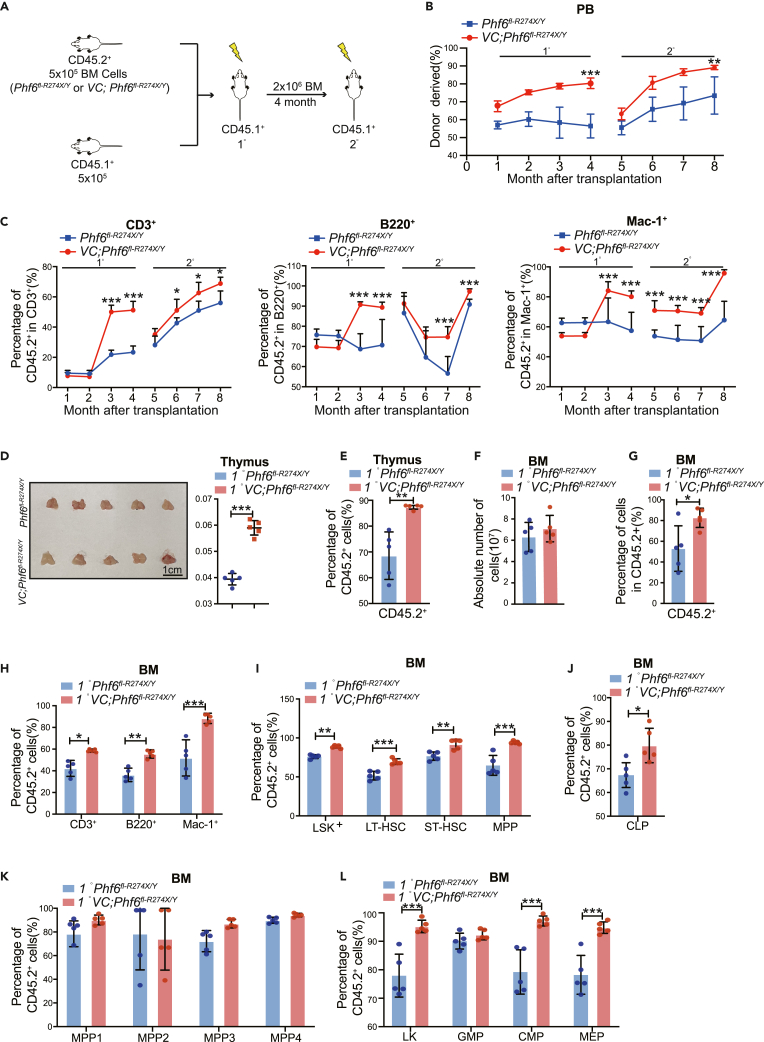

Phf6R274X mutation increases HSCs regeneration ability and skews differentiation toward T cells in competitive transplantation assay

To further probe the potential role of Phf6R274X mutation in regulating the function of HSCs, we performed serial competitive transplantations assay. We transplanted BM cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y or Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y CD45.2+ mice together with CD45.1+ BM cells into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice (Figure 3A). Every four months after each transplantation, we performed flow cytometric assay to examine the frequency of reconstituted cells (CD45.2+) in PB. The chimerism of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y cells (CD45.2+) in PB was significantly higher than that of the control in primary (1°) and secondary (2°) transplantations (Figure 3B). Notably, the percentage of donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) in CD3+ T cells was increased in the PB from the mice transplanted with Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y BM cells (Figure 3C). We also found that the weight of thymus was significantly higher in Vav-Cre1;Phf6fl-R274X/Y group than the controls in the 1° and 2° transplantations (Figure 3D, S3A), and the percentage of donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) were significantly increased in thymus of mice transplanted with Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y cells (Figure 3E). The absolute number of BM cells in mice transplanted with Vav-Cre1;Phf6fl-R274X/Y BM cells was equivalent to that of the controls in 1° and 2° transplantations (Figure 3F, S3B). The percentage of donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) were significantly increased in BM of mice transplanted with Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y cells when compared with that of the controls in primary (1°) and secondary (2°) transplantations (Figure 3G, S3C). Consistent with CD45.2+ T cells in PB, the percentage of donor-derived cells (CD45.2+) in CD3+ T cells were also increased in BM of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y recipients in 1° and 2° transplantations (Figures 3G–3I, S3D–S3F), indicating that the differentiation of Phf6R274X HSCs biased toward T cells. Interestingly, in LT-HSC/HPC fractions, the percentage of Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y derived cells in LSKs, LT-HSC, short term-HSC (ST-HSC), MPP, LKs, common-myeloid progenitors (CMP), MEP, and CLP was much higher than that of control in 1° transplantation (Figure 3J, S3G), suggesting that Phf6R274X increased the self-renewal ability of HSCs. Taken together, these results indicated that Phf6R274X mutation led to increase the hematopoietic reconstitution and skewed HSCs toward T cells differentiation.

Figure 3.

Phf6R274X mutation enhanced competitive hematopoietic reconstitution

(A) Schematic diagram showing the experimental design for serial competitive hematopoietic transplantation with BM cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice.

(B) The chimerism of donor-derived cell (CD45.2+) in PB of primary (1°) and secondary (2°) recipients (n = 5).

(C) The chimerism of donor-derived T, B, and myeloid cells in PB of primary (1°) and secondary (2°) recipients (n = 5).

(D) Photographs and weight of thymus of primary (1°) recipients at 4 months after transplantation (n = 5).

(E) The chimerism of donor-derived cell in thymus of primary (1°) recipients at fourth month after transplantation (n = 5).

(F) Absolute number of BM cells in primary (1°) recipients (n = 6). (G-L) The chimerism of donor-derived cell in BM of primary (1°) recipients at fourth month after transplantation (n = 6).

(G–L) (G) donor-derived cells (CD45.2+), (H) donor-derived T, B, and myeloid cells, (I) donor-derived LKS, LT-HSC, ST-HSC, and MPP cells, (J) donor-derived CLP, (K) donor-derived MPP1-4, (L) donor-derived LK, GMP, CMP, MEP. Data information: All mice for donor cells used were male mice of 8–10 weeks of age. In (B-L) data are shown as the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

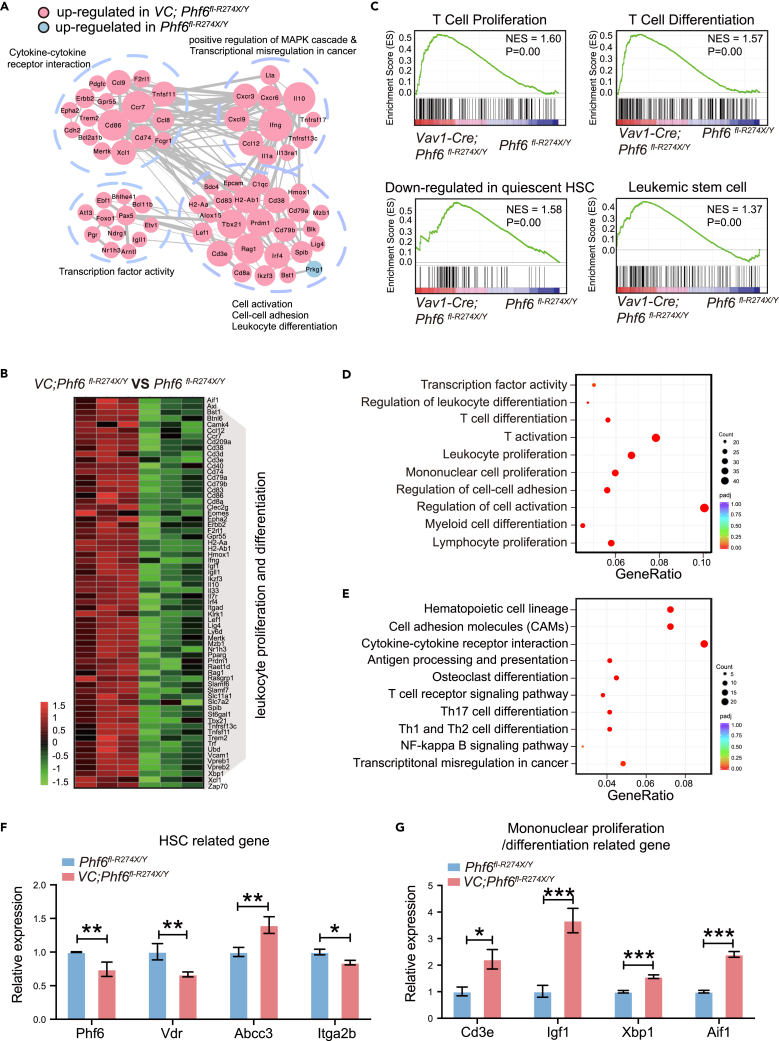

Phf6R274X mutation in HSCs lead to a distinct gene expression signature associated with cell proliferation and differentiation

To determine the underlying mechanism of Phf6R274X in regulating the function of HSC/HPCs, we performed RNA sequencing and analyzed the different expression profiles between Phf6R274X LSK cells and controls. Consistent with Phf6R274X-induced over-activation of HSCs in vivo, the different expression genes (DEGs) were enriched in cell viability-related signaling pathways, such as cell activation, adhesion, and leukocyte differentiation (Figure 4A). Furthermore, DEGs were also enriched in cancer-related pathways, such as cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, transcription factor activity, and positive regulation of MAPK cascade and transcription dysregulation (Figure 4A), suggesting Phf6R274X might involve in tumorigenesis. The expression profiles of Phf6R274X LSK cells showed 66 genes related to leukocyte proliferation and differentiation were upregulated (p < 0.05) (Figure 4B). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that the upregulated genes in Phf6R274X LSK cells were enriched in GRAHAM_NORMAL_QUIESCENT_VS._NORMAL_DIVIDING_DN and GAL_LEUKEMIC_STEM_CELL_DN pathway, as well as T cell in proliferation and differentiation (Figure 4C). Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that the upregulated genes in Phf6R274X LSK cells were associated with T cell activation, lymphocyte proliferation, and T cell differentiation (Figure 4D). Kyoto Encylopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis revealed active cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction pathway (Figure 4E). Interestingly, the genes related to the regulation of HSC function, such as Vdr and Itga2b were significantly downregulated, while Abcc3 was upregulated in Phf6R274X group (Figure 4F). The profiles derived from analyses were consistent with the experimental findings that Phf6R274X mutation enhanced the regeneration capacity of HSC. In addition, the mRNA expression of CD3e, Igf1, Xbp1, and Aif1, that were involved in T cell proliferation and differentiation, were increased in Phf6R274X LSK cells (Figure 4G), which further supported that Phf6R274X mutation activated the function of T cell.

Figure 4.

Phf6R274X mutation alters the gene expression profiles in HSC/HPCs

(A) Gene interaction analysis showing the significantly altered expression pattern in Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y BM LSK+ cells compared with control cells.

(B) Heatmap showing differential expression of 66 genes related to leukocyte proliferation and differentiation in Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice BM LSK+ cells. |Log2foldchange | > 1, p value <0.05 (n = 3).

(C) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for genes affected in the BM LSK+ cell from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice.

(D and E) GO and KEGG analysis of the up-regulated genes in Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y cells compared with Phf6fl-R274X/Y cells.

(F and G) Relative expression levels of Aif1, Cd3e, Igf1, and Xbp1 genes in BM LSK+ cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice. mRNA levels were normalized to the expression of GAPDH. Data information: in (F-G) data are shown as the mean ± SD. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001 by the Student’s t test.

Discussion

Phf6 is an important epigenetic regulatory gene, and its significance was anchored by clinical findings that numerous mutations were found in leukemia patients. However, current findings are mainly from studies using Phf6 deletion mutation mouse models. For example, Wendorff and Miyagi et al. demonstrated that Phf6 deletion increased the self-renewal ability of HSCs.8,9 As one of the most common mutation identified in both T-ALL and AML patients, the consequence of PHF6R274X mutation in the hematopoietic system are still largely unknown. In the current study, we generated a Phf6R274X knock-in mouse model which expressed Phf6R274X in the hematopoietic compartment. Consistent with Phf6-deficient mice in previous studies,6,7,8 VC;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice displayed an increase of HSCs pool in BM and enhanced self-renewal ability of LT-HSCs when compared to the control. This result suggests that VC;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice showed the phenotypes resembling Phf6 null mice. In contrast, the differentiation of Phf6R274X HSCs skewed toward T cells and Phf6R274X enhanced the activity of T cell activation, proliferation, and killing. This T cell phenotype was specific to VC;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice, indicating that PHF6R274X mutation has a unique role in T cell lineage differentiation and function, and further studies maybe needed. The changes in RBCs and B cells might be temporary for Phf6R274X mice. These data demonstrated that the function of Phf6R274X in hematopoiesis is altered.

PHF6R274X mutation frequently occurred in T-ALL and AML patients, suggesting that PHF6R274X might involve in leukemogenesis of AML and T-ALL. Several studies indicated that PHF6 functions as a tumor suppressor in T-ALL. For example, Wendorff and Yuan et al. observed that Phf6 loss promoted T-ALLs driven by ICN1 and JAK3 mutation.8,22 In contrast to tumor suppressing role seen in PHF6 in T-ALL, Phf6 deficiency was shown to inhibit the progression of BCR-ABL-induced B-ALL in vivo, indicated that Phf6 might possess an oncogenic role in B-ALL11. In this context, we found that Phf6R274X mice did not develop hematological malignancies spontaneously. RNA-Seq analysis showed more active transcriptome programming in Phf6R274X LSK cells when compared to controls. Gene expression profiling implicated in cell activation, cell-cell adhesion, and cell differentiation of Phf6R274X LSK cells, supporting the findings of Phf6R274X in HSC homeostasis. We also found that GEGs were enriched in genes related to leukemia stem cell (LSC), as LSC and normal HSC have been shown to share some common molecular mechanisms previously.23,24 Of these enriched genes, we found that Vdr, Abcc3, and Itga2b were also dysregulated in Phf6R274X mutant LSKs. It has been reported that Vdr, Itga2b, and Abcc3 directly regulated the function of HSCs.25,26,27 For example, Ewa Marcinkowska., et al. found that vitamin D receptor (VDR) is present in multiple types of blood cells. While the expression of VDR was silenced during differentiation of HSCs.26 Jon Frampton., et al. found that the product of the Itga2b gene, CD41 contributes to the function of HSCs. The expression of Itga2b (CD41) was negative during the onset of definitive hematopoiesis.25 In addition, Chi Wai Eric So., et al. found that patients with HSC-like AML had higher expression of ABCC3. Knockdown of ABCC3 by two independent shRNAs inhibited the survival of MLL-rearranged HSCs.27 Moreover, D Givol1., et al. found that some of the “signature” genes of LSC are alike within the cell stage of HSCs28 including these three genes that were enriched in GAL_LEUKEMIC_STEM_CELL_DN pathway by our analysis. Thus, we speculated that these three genes share some expression similarities in LSC and HSC, although more functional studies are needed. It also implicated that Phf6R274X may affect the function of HSCs and play a role in leukemia. In this regard, Phf6R274X seemed to enhance the self-renewal capacity of HSCs, potentially to play roles in leukemia development. In addition, a set of genes (Aif1, Cd3e, Igf1, and Xbp1) associated with T cells activation were upregulated in the Phf6R274X mutation group, which might partially explain Phf6R274X promoted the function of T cells. The transcriptional regulation of T cells development via lineage-specific factors has been well characterized.29 Previous study found that PHF6 binds to nucleosomes surrounding the TSSs of T-cell-specific genes, coordinating chromatin compaction, and blocking the binding of T cell-specific transcription factors.30 Thus, chromatin regions that became more accessible upon Phf6 mutation (or loss) could be enriched for motifs of transcription factors associated with the development of T-ALL. In view of this, we speculated that chromatin binding for T cell-specific TFs is more accessible due to Phf6R274X mutation, and T cell-specific transcription factors might bind and activate the transcriptome programming in LSK cells, and the up-regulated genes that involved in T cell proliferation and differentiation, ultimately led to the expansion of lymphoid-primed progenitor cells.

PHF6R274X is located on the ePHD2 domain and is essential for the function of PHF6,2,15 and we are particularly interested in the effect of R274X mutation on protein level since it is a nonsense mutation. We determined that the mRNA level of Phf6R274X was significantly decreased in Phf6R274X-mutated mice (Figure 1F). Moreover, we found that the degradation of Phf6R274X mRNA was faster than wild-type Phf6 mRNA in BM cells following Actinomycin-D (10 μg/mL) treatment (data not shown). It indicated that although Phf6R274X gene could successfully be transcribed to mRNA, the stability of Phf6R274X mRNA was reduced. Since the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) is a known cellular mechanism designed to degrade mRNAs to control proper levels of gene expression by removing mRNAs that potentially encode deleterious truncated proteins,31,32 we speculated that the R274X mutation rendered its mRNA unstable, less mutant protein is synthesized or if synthesized, be degraded due to its structure instability, and the function of protein was further impaired. The phenotype discrepancies seen between the Phf6 knockout mice and Phf6R274X knock-in mice may lies in this, and further studies is needed to fully elucidate the regulatory role of PHF6 in hematopoiesis. In conclusion, we found that Phf6R274X mutation frequently existed in T-ALL and AML patients. Notably, Phf6R274X mutation results in increased self-renewal of HSCs and skewed differentiation to T cells in vivo. The Phf6R274X mice is a suitable mouse model for further studies in the physiology/pathophysiology of hematopoiesis and leukemia and the molecular pathways regulated by Phf6 mutations.

Limitations of study

Here in this study, we generated a Phf6R274X knock-in mouse model to elucidate the effect of Phf6R274X mutation in hematopoiesis in vivo. While we demonstrated that Phf6R274X mutation promoted self-renewal ability of HSCs and T cells proliferation and activation, the underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated. Our data suggested that the phenotypes of Phf6R274X mice and Phf6-deficient mice have both similarities and differences, suggesting a differential role of Phf6R274X mutation. Further work is needed to explore the potential role of PHF6R274X mutation in leukemia progression.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Rabbit monoclonalAnti-PHF6 | Sigma | Cat# HPA001023; RRID: AB_1079606 |

| Anti-Rabbit monoclonal anti-GAPDH | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#: CST2118 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.1 (APC) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 17-0453-82; RRID: AB_469398 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.1 (APC-Cy7) | Biolegend | Cat#: 560579 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.1 (Percp-Cy5.5) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 45-0453-82 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.2 (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-0454-83; RRID: AB_465679 |

| Anti-mouse CD45.2 (Percp-Cy5.5) | eBioscience | Cat#: 45-0453-82; RRID: AB_953590 |

| Anti-mouse CD3 (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-0454-83; RRID: AB_465679 |

| Anti-mouse CD3 (FITC) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100204 |

| Anti-mouse CD3 (Biotin) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 13-0032-82; RRID: AB_2572762 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b (Mac-1) (APC-Cy7) | Biolegend | Cat#: 101226 |

| Anti-mouse CD11b (Mac-1) (Alexa Fluor780) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 47-0112-82; RRID: AB_1603193 |

| Anti-mouse B220 (CD45R) (PerCP-Cyanine5.5) | eBioscience | Cat#: 45-0452-82; RRID: AB_1107006 |

| Anti-mouse B220 (CD45R) (Biotin) | eBioscience | Cat#: 36-0452-85; RRID: AB_469753 |

| Anti-mouse CD135 (Flk2) (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-1351-82 |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6G (Gr-1) (Biotin) | eBioscience | Cat#: 13-5931-85; RRID: AB_466801 |

| Anti-mouse CD34 (FITC) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 11-0341-82; RRID: AB_465021 |

| Anti-mouse Ter119 (Biotin) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 13-5921-85; RRID: AB_466798 |

| Anti-mouse CD16/32 (APC) | eBioscience | Cat#: 17-0161-82; RRID: AB_469356 |

| Anti-mouse CD16/32 (FITC) | eBioscience | Cat#: 11-0161-82; RRID: AB_464956 |

| Anti-mouse CD127 (IL-7R) (PE) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 12-1271-82 |

| Anti-mouse CD44 (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-0441-82; RRID: AB_465664 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 (PE-Cy7) | eBioscience | Cat#: 25-0041-82; RRID: AB_469576 |

| Anti-mouse CD4 (Biotin) | eBioscience | Cat#: 13-0043-85; RRID: AB_466334 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a (APC) | Biolegend | Cat#: 100712 |

| Anti-mouse CD8a (Biotin) | eBioscience | Cat#: 13-0081-85; RRID: AB_466347 |

| Anti-mouse Streptavidin (APC) | Biolegend | Cat#: 405207 |

| Anti-mouse Streptavidin (APC-eFlour 780) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 47-4317-82; RRID: AB_10366688 |

| Anti-mouse Sca-1 (PE) | Invitrogen | Cat#: MA5-17890 |

| Anti-mouse Sca-1 (PE-Cy7) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 25-5918-81 |

| Anti-mouse c-Kit (APC) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 17-1171-82; RRID: AB_469430 |

| Anti-mouse c-Kit (PE) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 12-1171-82; RRID: AB_465813 |

| Anti-mouse c-Kit (PE-Cy7) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 25-1178-42; RRID: AB_10718535 |

| Anti-mouse CD25 (APC-Cy7) | Biolegend | Cat#: 557658 |

| Anti-mouse CD69 (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-0691-82; RRID: AB_465732 |

| Anti-mouse CD48 (FITC) | eBioscience | Cat#: 11-0481-82; RRID: AB_465077 |

| Anti-mouse CD150 (PE-Cy7) | eBioscience | Cat#: 25-1502-82; RRID: AB_10805742 |

| Anti-Mouse IFNγ (PE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12-7319-81; RRID: AB_1272169 |

| Anti-Mouse TNFα (FITC) | eBioscience | Cat#: 11-7349-82; RRID: AB_465424 |

| Annexin V | Biolegend | Cat#: 640908 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| TRIzol™ Reagent | Invitrogen | Cat#: 15596026CN |

| Fast SYBR Green Master Mix | Clontech | Cat#: 639676 |

| Mouse CD117 MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#130-091-224 |

| DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix | Thermo Fisher | Cat#: K1082 |

| DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#D1306 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Qiagen | Cat#: 69506 |

| Lineage Cell Depletion Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#: 130-110-470 |

| TransScript® All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR | Trans | Cat#: AT341-01 |

| T Cell Activation/Expansion Kit | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat#: 130-093-627 |

| Deposited data | ||

| RNA-seq | NOVOGENE | GEO: GSE201475 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: C57BL/6J | The Model Organisms Center, Inc | N/A |

| Mouse: B6.SJL | The Model Organisms Center, Inc | N/A |

| Mouse: Vav1-Cre | The Model Organisms Center, Inc | N/A |

| Mouse: Phf6fl-R274X | The Model Organisms Center, Inc | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| qPCR primers see Table S1 | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8 | This study | N/A |

| FlowJo | This study | N/A |

| Adobe Illustrator 2021 | This study | N/A |

| DESeq2 R package | This study | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xiaomin Wang (wangxiaomin@ihcams.ac.cn).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed materials transfer agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

A 15.76 kb genomic DNA including Phf6 exon 8-11, two loxP sites, the FRT-flanked Neo selection cassette, and Phf6R274X mutation in exon 8 (c.820C > T) used to construct the targeting vector by infusion (Figure S1A). Then, the mice were mated with Vav1-Cre transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Vav1 promoter. The Phf6R274X mutation expressed in the hematopoietic cells at the embryonic stage with Cre activity. As expected, half of the offspring were wild-type (Phf6fl-R274X/Y), and the other half were Phf6R274X mice (Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y) (Figure S1B). All mice used in the experiments were male mice of 8-week-old. Mice were maintained at the specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility of the State Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology (SKLEH). All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), the Institute of Hematology, and Blood Diseases Hospital (CAMS/PUMC). All surgery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia, and every effort was made to minimize mouse suffering. The primers used for genotyping PCR are in Table S1.

Method details

Real time PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and cDNA was synthesized. RT-PCR was performed in triplicate using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Clontech, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions on QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR detector (ThermoFisher, USA). The primers used for RT-PCR are in Table S2.

Western blotting analysis

Western blot analysis was performed using standard protocols. Antibodies used in this study were as followings: PHF6 antibody was used at a 1:1000 dilution (Sigma). GAPDH antibody was used at a 1:1000 dilution (Cell Signaling Technology). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Bio-Rad, USA).

Bone marrow transplantation

A total of 5×105 BM cells was harvested from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y (donor mice, CD45.2+) and mixed with the same number of BM cells from B6.SJL (competitor, CD45.1+). The CD45.1+ recipient mice were lethally irradiated (9Gy, X-ray). Every recipient mouse was transplanted with 1×106 mixed cells injected by lateral tail vein. The chimerism rates of CD45.2+ cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mice were examined every 4 weeks. BM was examined at the fourth months after transplantation. For the serial competitive transplantation assay, 2×106 BM cells from primary recipients were injected into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice. All mice used were 8-10 weeks of age.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from peripheral blood (PB), bone marrow (BM), spleen and thymus. Red blood cells from PB, BM, spleen and thymus were lysed using RBC lysis buffer. Cells were stained with antibodies at 4°C for 30min in the absence of light. Then, cells were washed and resuspended with PBS and the positive cell fragment was stained with antibodies. Data were acquired on FACS LSR II instrument (BD Biosciences, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo software 10.4. A list of antibodies used for flow cytometry is indicated in the key resources table.

T cell isolation and culture

MACS magnetic cell sorting was performed according to manufacturer's instruction (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) to isolate Primary murine T cells from spleen. Briefly, the primary spleen cells from Phf6fl-R274X/Y and Vav1-Cre;Phf6fl-R274X/Y mice were harvested and labeled with CD3 Biotin. Anti-biotin MicroBeads were incubated for subsequent secondary labeling. After magnetic labeling, cell suspension was separated with MACS MS columns. Then, diluted cells into a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml with fresh RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml) and mIL-2 (10ng/ml). Anti-CD3/CD28 was added to activate the primary T cells. The cells were further incubated in a 37°C incubator supplied with 5% CO2.

Detection of CD69 and CD25 expression

For T cell activation experiments, after stimulating with anti-CD3/ CD28 for 12h or 72h, cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS. Labeled with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD8 and anti-CD69 or anti-CD25 simultaneously at 4°C for 30 min, hen analyzed with flow cytometer.

CFSE staining

CFSE staining was performed to evaluate the proliferation of primary T cells after stimulation. 1 × 106 primary T cells/ml were pre-incubated with 5 μM CFSE at 37°C for 20 min, washed twice with 10% FBS/RPMI 1640 medium. Then stimulated with Anti-CD3/CD28 for additional 3 days. After stimulation, cells were stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 at 4°C for 30min, then analyzed with flow cytometer.

Intracellular cytokine staining

After CD3+ T cells stimulating with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24h, cells were stimulated with 50ng/ml PMA, 1 nM ionomycin, and GolgiPlug in 10% FBS/RPMI 1640 medium at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator for 6-8 h. Cells were washed and stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 at 4°C for 30min. Intracellular cytokines staining were performed using Fixation/Permeabilization Solution Kit (BD Bioscience, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

T cell killing assay

After CD3+ T cells stimulating with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24h, 2 × 105 cells were cocultured with 2 × 104 primary spleen cells from MAL-AF9 mice for 12h. All cells were harvested, washed and stained with Annexin V at 4°C for 30min, then analyzed with flow cytometer.

RNA sequencing

BM cells were stained with lineage markers (including CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, Mac1, Gr1 and Ter119), and Lin- cells were enriched with Biotin-antibody microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Cologne, Germany). Then these cells were stained with Sca-1 and c-Kit antibodies, and LSK+ cells were sorted by the Aria III (BD Biosciences, USA). RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent and 1μg RNA per sample was used for RNA sample preparations. Transcriptome sequencing was performed on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to a total target depth of 10 million 150 bp paired end reads. Differential expression analysis was performed by DESeq2 R package (1.16.1). RNA-Seq data are available at GEO under accession number GSE201475.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (8.4.0). Distribution was tested using the modified Shapiro-Wilks method. When parameters followed Gaussian distribution, Student’s t test was used for two groups’ analyses and one-way ANOVA was used for comparing more than two groups to evaluate the statistical significance. The student's t test was performed to determine the statistical significance (∗ P < 0.05, ∗∗ P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ P < 0.001). Sample size was determined according to experience or the previously published papers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFE0203000 to YJC), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270153, 82070169 to XMW), and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, CIFMS (2021-I2M-1-040 to WPY). Haihe Laboratory of Cell Ecosystem Innovation Fund (22HHXBSS00037 to WPY, YJC and YGC).

Author contributions

X.M.W. and W.P.Y. conceived the project, supervised the research, and revised the paper. Y.J.L., S.N.Y., and T.X.G. performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. T.X.G., S.B.H., F.Z., W.Z.Y., and Y.G.C. assisted with the mouse experiments, flow cytometry analysis, and data processing. Y.J.C. and E.L.J. participated in results and paper discussion. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Inclusion and diversity

We support inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

Published: May 5, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106817.

Contributor Information

Weiping Yuan, Email: wpyuan@ihcams.ac.cn.

Xiaomin Wang, Email: wangxiaomin@ihcams.ac.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Data

RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE201475, and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

Code

This paper does not report original code.

Other

None.

References

- 1.Landais S., Quantin R., Rassart E. Radiation leukemia virus common integration at the Kis2 locus: simultaneous overexpression of a novel noncoding RNA and of the proximal Phf6 gene. J. Virol. 2005;79:11443–11456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11443-11456.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Z., Li F., Ruan K., Zhang J., Mei Y., Wu J., Shi Y. Structural and functional insights into the human Börjeson-Forssman-Lehmann syndrome-associated protein PHF6. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10069–10083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.535351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aasland R., Gibson T.J., Stewart A.F. The PHD finger: implications for chromatin-mediated transcriptional regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:56–59. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88957-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang J., Leung J.W.c., Gong Z., Feng L., Shi X., Chen J. PHF6 regulates cell cycle progression by suppressing ribosomal RNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:3174–3183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.414839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loontiens S., Dolens A.C., Strubbe S., Van de Walle I., Moore F.E., Depestel L., Vanhauwaert S., Matthijssens F., Langenau D.M., Speleman F., et al. PHF6 expression levels impact human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.599472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu Y.C., Chen T.C., Lin C.C., Yuan C.T., Hsu C.L., Hou H.A., Kao C.J., Chuang P.H., Chen Y.R., Chou W.C., Tien H.F. Phf6-null hematopoietic stem cells have enhanced self-renewal capacity and oncogenic potentials. Blood Adv. 2019;3:2355–2367. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McRae H.M., Garnham A.L., Hu Y., Witkowski M.T., Corbett M.A., Dixon M.P., May R.E., Sheikh B.N., Chiang W., Kueh A.J., et al. PHF6 regulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and its loss synergizes with expression of TLX3 to cause leukemia. Blood. 2019;133:1729–1741. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-07-860726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyagi S., Sroczynska P., Kato Y., Nakajima-Takagi Y., Oshima M., Rizq O., Takayama N., Saraya A., Mizuno S., Sugiyama F., et al. The chromatin-binding protein Phf6 restricts the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2019;133:2495–2506. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wendorff A.A., Quinn S.A., Rashkovan M., Madubata C.J., Ambesi-Impiombato A., Litzow M.R., Tallman M.S., Paietta E., Paganin M., Basso G., et al. Phf6 loss enhances HSC self-renewal driving tumor initiation and leukemia stem cell activity in T-ALL. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:436–451. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loontiens S., Vanhauwaert S., Depestel L., Dewyn G., Van Loocke W., Moore F.E., Garcia E.G., Batchelor L., Borga C., Squiban B., et al. A novel TLX1-driven T-ALL zebrafish model: comparative genomic analysis with other leukemia models. Leukemia. 2020;34:3398–3403. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0938-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meacham C.E., Lawton L.N., Soto-Feliciano Y.M., Pritchard J.R., Joughin B.A., Ehrenberger T., Fenouille N., Zuber J., Williams R.T., Young R.A., Hemann M.T. A genome-scale in vivo loss-of-function screen identifies Phf6 as a lineage-specific regulator of leukemia cell growth. Genes Dev. 2015;29:483–488. doi: 10.1101/gad.254151.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Vlierberghe P., Palomero T., Khiabanian H., Van der Meulen J., Castillo M., Van Roy N., De Moerloose B., Philippé J., González-García S., Toribio M.L., et al. PHF6 mutations in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:338–342. doi: 10.1038/ng.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Vlierberghe P., Patel J., Abdel-Wahab O., Lobry C., Hedvat C.V., Balbin M., Nicolas C., Payer A.R., Fernandez H.F., Tallman M.S., et al. PHF6 mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:130–134. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori T., Nagata Y., Makishima H., Sanada M., Shiozawa Y., Kon A., Yoshizato T., Sato-Otsubo A., Kataoka K., Shiraishi Y., et al. Somatic PHF6 mutations in 1760 cases with various myeloid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2016;30:2270–2273. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z., Li F., Ruan K., Zhang J., Mei Y., Wu J., Shi Y. Structural and functional insights into the human Borjeson-Forssman-Lehmann syndrome-associated protein PHF6. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:10069–10083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.535351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q., Qiu H., Jiang H., Wu L., Dong S., Pan J., Wang W., Ping N., Xia J., Sun A., et al. Mutations of PHF6 are associated with mutations of NOTCH1, JAK1 and rearrangement of SET-NUP214 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:1808–1814. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.043083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossmann V., Haferlach C., Weissmann S., Roller A., Schindela S., Poetzinger F., Stadler K., Bellos F., Kern W., Haferlach T., et al. The molecular profile of adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: mutations in RUNX1 and DNMT3A are associated with poor prognosis in T-ALL. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:410–422. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh H.J., Lee S.H., Yoo K.H., Sung K.W., Koo H.H., Jang J.H., Kim K., Kim S.J., Kim W.S., Jung C.W., et al. Gene mutation profiles and prognostic implications in Korean patients with T-lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann. Hematol. 2013;92:635–644. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1664-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M., Xiao L., Xu J., Zhang R., Guo J., Olson J., Wu Y., Li J., Song C., Ge Z. Co-existence of PHF6 and NOTCH1 mutations in adult T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncol. Lett. 2016;12:16–22. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Todd M.A.M., Ivanochko D., Picketts D.J. PHF6 Degrees of separation: the Multifaceted roles of a chromatin Adaptor protein. Genes. 2015;6:325–352. doi: 10.3390/genes6020325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caruso A., Licenziati S., Corulli M., Canaris A.D., De Francesco M.A., Fiorentini S., Peroni L., Fallacara F., Dima F., Balsari A., Turano A. Flow cytometric analysis of activation markers on stimulated T cells and their correlation with cell proliferation. Cytometry. 1997;27:71–76. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19970101)27:1<71::aid-cyto9>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan S., Wang X., Hou S., Guo T., Lan Y., Yang S., Zhao F., Gao J., Wang Y., Chu Y., et al. PHF6 and JAK3 mutations cooperate to drive T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia progression. Leukemia. 2021;36:370–382. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01392-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reya T., Morrison S.J., Clarke M.F., Weissman I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park I.K., Qian D., Kiel M., Becker M.W., Pihalja M., Weissman I.L., Morrison S.J., Clarke M.F. Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:302–305. doi: 10.1038/nature01587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumon S., Walton D.S., Volpe G., Wilson N., Dassé E., Del Pozzo W., Landry J.R., Turner B., O'Neill L.P., Göttgens B., Frampton J. Itga2b regulation at the onset of definitive hematopoiesis and commitment to differentiation. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak U., Janik S., Marchwicka A., Łaszkiewicz A., Jakuszak A., Cebrat M., Marcinkowska E. Investigating the role of Methylation in silencing of VDR gene expression in normal cells during hematopoiesis and in their leukemic counterparts. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9091991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeisig B.B., Fung T.K., Zarowiecki M., Tsai C.T., Luo H., Stanojevic B., Lynn C., Leung A.Y.H., Zuna J., Zaliova M., et al. Functional reconstruction of human AML reveals stem cell origin and vulnerability of treatment-resistant MLL-rearranged leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gal H., Amariglio N., Trakhtenbrot L., Jacob-Hirsh J., Margalit O., Avigdor A., Nagler A., Tavor S., Ein-Dor L., Lapidot T., et al. Gene expression profiles of AML derived stem cells; similarity to hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:2147–2154. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullighan C.G., Goorha S., Radtke I., Miller C.B., Coustan-Smith E., Dalton J.D., Girtman K., Mathew S., Ma J., Pounds S.B., et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446:758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soto-Feliciano Y.M., Bartlebaugh J.M.E., Liu Y., Sánchez-Rivera F.J., Bhutkar A., Weintraub A.S., Buenrostro J.D., Cheng C.S., Regev A., Jacks T.E., et al. PHF6 regulates phenotypic plasticity through chromatin organization within lineage-specific genes. Genes Dev. 2017;31:973–989. doi: 10.1101/gad.295857.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Popp M.W.L., Maquat L.E. Organizing principles of mammalian nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013;47:139–165. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed R., Sarwar S., Hu J., Cardin V., Qiu L.R., Zapata G., Vandeleur L., Yan K., Lerch J.P., Corbett M.A., et al. Transgenic mice with an R342X mutation in Phf6 display clinical features of Börjeson-Forssman-Lehmann Syndrome (BFLS) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021;30:575–594. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data

RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE201475, and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Accession numbers are listed in the key resources table.

Code

This paper does not report original code.

Other

None.