Abstract

Introduction

This perspective paper addresses the US Hispanic/Latino (herein, Latino) experience with regards to a significant public health concern—the underrepresentation of Latino persons in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD) clinical trials. Latino individuals are at increased risk for AD/ADRD, experience higher disease burden, and low receipt of care and services. We present a novel theoretical framework—the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment—which considers multi‐level barriers and their impact on Latino trial recruitment.

Methods

Based on a review of the peer‐reviewed literature and our lived experience with the Latino community, we drew from our interdisciplinary expertise in health equity and disparities research, Latino studies, social work, nursing, political economy, medicine, public health, and clinical AD/ADRD trials. We discuss factors likely to impede or accelerate Latino representation, and end with a call for action and recommendations for a bold path forward.

Results

In the 200+ clinical trials conducted with over 70,000 US Americans, Latino participants comprise a fraction of AD/ADRD trial samples. Efforts to recruit Latino participants typically address individual‐ and family‐level factors (micro‐level) such as language, cultural beliefs, knowledge of aging and memory loss, limited awareness of research, and logistical considerations. Scientific efforts to understand recruitment barriers largely remain at this level, resulting in diminished attention to upstream institutional‐ and policy‐level barriers, where decisions around scientific policies and funding allocations are ultimately made. These structural barriers are comprised of inadequacies or misalignments in trial budgets, study protocols, workforce competencies, healthcare‐related barriers, criteria for reviewing and approving clinical trial funding, criteria for disseminating findings, etiological focus and social determinants of health, among others.

Conclusion

Future scientific work should apply and test the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment to examine structural recruitment barriers for historically underrepresented groups in AD/ADRD research and care.

Keywords: clinical trials, funding and regulatory strategies, micro‐meso‐macro framework, recruitment, underrepresented groups

1. INTRODUCTION

US Hispanic/Latino/a/x 1 (herein, Latino) persons are the nation's largest minoritized racial/ethnic group in the United States, comprising 19% of the population. Latino individuals account for half (52%) of the nation's population growth, and are expected to increase from 62.5 million to 111 million people by 2060. 2 Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD) are life‐threatening neurocognitive disorders that have garnered significant attention in recent decades in almost every sector of society. Although living with AD/ADRD is challenging for all people and families, current evidence highlights significant disparities. For example, Latino and Black Americans have higher disease rates than non‐Latino White individuals, and they experience delayed diagnosis, poor quality treatment, and low access to evidence‐based, non‐pharmacological interventions. 3

This paper addresses the Latino experience in the United States (US) with regards to a significant public health concern—the underrepresentation of the Latino population in AD/ADRD clinical trials—and issues a call to address the structural barriers that sustain such underrepresentation through the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment. Latino individuals have high rates of AD/ADRD (1.5 times greater than non‐Latino White persons) and are predicted to experience an 832% increase in rates by 2060. 4 Latino individuals live longer with AD/ADRD, 5 have higher rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms, 6 and underutilize long‐term services and supports. 7 Of the more than 200 clinical trials being conducted with over 70,000 US Americans, 8 Latino participants comprise a fraction of those actually enrolled despite accounting for 19% of the US population. Approvals of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of promising pharmacological treatments are key, yet clinical samples fall short of including Latino participants. For example, aducanamab—a FDA‐approved drug to treat AD/ADRD—was tested on a population comprised of only 3% Latino participants. 9 In addition, Latino individuals accounted for 4.4% of participants in North American sites of the A4 Study, a phase 3 preclinical AD trial. 10 The recent lecanemab drug trial indicated that 12.4% of study participants are Latino, thus showing improvement in recruitment target goals. 11 Earlier trials before the Clarity AD study are presented in Table 1 which includes rates for Latino sample representation across anti‐amyloid immunotherapy studies published within the last decade. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 As noted, Latino representation was either not reported, or ranged from zero to 3.3% before the lecanemab drug trial.

TABLE 1.

Historic low inclusion of Latino populations in phase III trials of anti‐amyloid immunotherapies.

| Anti‐amyloid immunotherapy | Study | Year of publication | % Latino participants in sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Generation | |||

| Bapineuzumab | Salloway et al. 12 | 2014 | Not reported |

| 2nd Generation | |||

| Solanezumab |

EXPEDITION 1 & 2 studies. Doody et al. 13 |

2014 | None |

| Gantenerumab |

SCarlet RoAD study Ostrowitzki et al. 14 |

2017 | Not reported |

| Solanezumab |

EXPEDITION 3 study. Honig et al. 15 |

2018 | None |

| 3rd Generation | |||

| Donanemab |

TRAILBLAZER‐ALZ study. Mintun et al. 16 |

2021 | 3.3% |

| Aducanumab |

ENGAGE and EMERGE studies. Budd Haeberlein et al. 17 |

2022 | 3.0% |

| Lecanemab |

Clarity AD study. van Dyck et al. 11 |

2023 | 12.4% |

The need to diversify AD/ADRD trial cohorts is critical and long overdue. Several calls to action have underscored the societal and scientific imperatives for diversifying trial cohorts. 8 , 9 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 In fact, several National Institutes of Health (NIH) scientific initiatives and strategies highlight the importance of increasing the representativeness of trial samples, including funding innovations in science on diversity, recruitment, and retention in aging research. 21 However, the NIH has systematically awarded scientists with federal grant funding resulting in limited evidence to inform AD/ADRD among the Latino population, as well as other racial and ethnic groups. 22 The rationale to diversify cohorts and address AD/ADRD health disparities is predicated on sound and rigorous scientific principles, 5 , 18 , 23 , 24 in order to (1) safeguard ethical research principles such as justice, beneficence, and respect for persons; (2) elucidate heterogeneity in causal mechanisms and responses to treatments and care; (3) create robust AD/ADRD estimates based on adequately powered studies including determinants of population‐level differences; (4) enhance research designs and methods that address health equity considerations; (5) foster innovations in recruitment and retention; and (6) understand cultural and sociopolitical nuances in decision‐making, help‐seeking, and daily practices that impact health disparities.

1. RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the peer‐reviewed literature using traditional sources (e.g., PubMed) which revealed low participation of Hispanic/Latino (herein, Latino) people in AD/ADRD clinical trials and minimal attention to structural barriers to participation. This situation is unfortunate considering their increased dementia risk, and burden of disease

Interpretation: The main foci of this perspective paper are to (a) elucidate upstream institutional‐ and policy‐level barriers that play a role in Latino people's AD/ADRD trial participation; b) propose a novel theoretical framework that considers micro‐, meso‐, macro level barriers; and c) issue a call to action to address structural barriers.

Future directions: A bold path forward is needed to ensure fairness and equity in AD/ADRD trials, close the racial and ethnic disparity gap in diagnosis, treatment and care, and optimize “good science.” Future efforts should account for structural barriers among all historically underrepresented people in AD/ADRD research and care.

Efforts to recruit Latino participants to clinical trials largely address individual‐ and family‐level factors, such as language, cultural beliefs, knowledge of aging and memory loss, limited awareness of research in general, and logistical considerations. 20 , 25 , 26 Such downstream, micro‐level barriers require critical scientific efforts to recruit Latino individuals; however, scientific efforts to understand barriers have typically remained at this level. As a result, less attention has been devoted to recruitment barriers, as well as facilitators, at the upstream institutional and policy levels, where decisions around scientific policies, protocols, resources and their implementation are ultimately made.

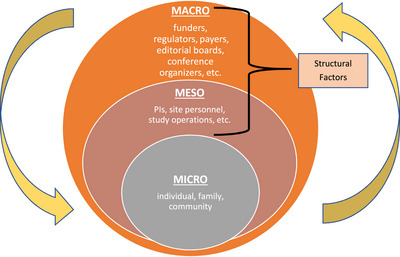

In this paper, we present a framework, titled the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment, that incorporates all three levels of barriers (see Figure 1), but with an enhanced focus and discussion around institutional (meso‐level) and policy (macro‐level) upstream dimensions centered around the US Latino experience. These meso‐ and macro‐level dimensions drive scientific policies and financing of infrastructures that ultimately impact clinical trial recruitment and retention of Latino study participants in the US. We begin by introducing well‐documented micro‐level barriers, and then move to more detailed discussions of structural barriers. We end with a call for action and recommendations for a bold path forward.

FIGURE 1.

The micro‐meso‐macro framework for diversifying AD/ADRD trial recruitment. Abbreviation: PI, principal investigator

2. OUR LIVED EXPERIENCE, EXPERTISE, AND THE METHODOLOGICAL PROCESS THAT LED TO THE FRAMEWORK

We drew from our combined expertise in health equity and health disparities research, Latino studies, social work, nursing, political economy, medicine, public health, and clinical trials on AD/ADRD, to stimulate debate on structural barriers that have impeded Latino participation in AD/ADRD trials for decades. Our process was more than a theoretical exercise: Through the experiential evidence method 27 , 28 that honors the knowledge gained from direct contact with Latino participants, communities, and large‐scale organizations, we engaged in multiple, iterative consensus meetings and documented the theoretical origins of the framework, the concomitant barriers at each level, and recommendations. Individually and collectively, we have lived experience as investigators from underrepresented groups and specifically with the US Latino community (as well as Latin America and the Caribbean), and have served in high‐level executive leadership positions wherein AD/ADRD research gaps and opportunities are routinely identified. Our process was intensive as well as iterative: We met as a group over multiple formal meetings to discuss recruitment and retention issues across numerous research projects and recruitment initiatives at the local and national levels. We documented our discussions, highlighted central themes (framework levels) and subthemes (barriers), as well as recommendations (at the meso and macro levels). We drew from the lived experiences of research participants we engage with in our scientific work whose voices consistently echoed in our discussions on barriers and facilitators to trial recruitment.

In the following section, we present a novel framework to identify factors likely to impede or accelerate Latino representation in clinical AD/ADRD trials.

3. MICRO‐LEVEL BARRIERS TO LATINO REPRESENTATION IN CLINICAL AD/ADRD TRIALS

Micro‐level barriers related to Latino participation in clinical AD/ADRD trials are well documented. 19 , 20 , 25 , 29 Our framework respects and affirms that Latino individuals and Latino families have culturally‐laden beliefs and personal knowledge about normative aging processes, illness attributions, memory loss, stigmatization around non‐normative behaviors, and whom to approach for information and assistance. 30 , 31 Notwithstanding, we acknowledge that such beliefs—although deemed culturally‐prescribed—interact continually with meso‐ and macro‐level factors, which, in combination, result in increased challenges for researchers to plan for and achieve full and informed participation from Latino individuals in AD/ADRD clinical trials.

Latino families face challenges in distinguishing between normal age‐related changes in cognition and those signaling the need for more thorough cognitive evaluations, resulting in delays in help‐seeking until later disease stages. 32 This situation can result from a lack of knowledge about AD/ADRD, 20 , 33 , 34 low access to information and to early detection and evidence‐based care, 3 , 7 and cultural values and beliefs that may interrupt early detection, among others. For example, collectivistic beliefs stemming from the cultural concept known as familismo (the central role of the family unit in decision‐making) may influence Latino individuals to seek encouragement and guidance from family members before seeking advice from healthcare professionals. 33 , 34 In addition, the Latino expectation of personalismo (the quality and trustworthiness of interpersonal interactions) can be thwarted when providers’ (and by extension researchers’) time with them in the care visit or encounter is brief or hurried, therefore limiting opportunities to establish warm and personal relationships, build confianza (trust), respeto (respect), and dignidad (dignity). 29 , 35 Thus, follow‐through with treatment regimens and referrals (for subsequent cognitive screening, specialist visits for diagnostic workups, etc.) may be delayed, or worse, not occur.

4. MESO‐LEVEL BARRIERS TO LATINO REPRESENTATION IN CLINICAL AD/ADRD TRIALS

Meso‐level barriers comprise interrelated institutional and organizational factors that impact the physical and human resource infrastructure available to conduct clinical trials. For example, the manner in which clinical trial protocols are conceptualized, designed, managed, budgeted, and deployed has an important influence on the participation of underrepresented groups, as they may omit the consideration of priorities, values and constraints that influence study participation.

4.1. Clinical trial budgets

One barrier is the limited funding allocated to the recruitment of underrepresented populations. At the site level, budget line items related to recruitment efforts rely on insufficient funds for bilingual and bicultural outreach specialists rooted in Latino communities who act as liaisons between the participants and research sites. Similarly, site‐level budgets typically do not budget enough effort for PIs and other key personnel to spend quality and sustained time interacting with Latino communities. At the administrative core or central trial office, budgets are thin and rarely cover the promotion of large‐scale national campaigns led by Latino communication and outreach specialists leveraging culturally‐ and linguistically‐congruent recruitment methods hailed by recruitment experts. 36

4.2. Language capabilities

The lack of a bilingual/bicultural workforce in clinical trials hampers the language and cultural congruency, and the inclusion needed to facilitate successful outreach, recruitment, and engagement of clinical trial participants. 19 Only a fraction of site‐level clinical trials have Spanish‐speaking personnel, and most do not have the requisite knowledge of trial‐specific procedures in Spanish. Most trial personnel do not identify as Latino and lack the bilingual and cultural humility skills necessary for clinical trial research. This limitation includes not only clinical personnel such as physicians and nurses but other personnel that have direct contact with research participants such as clinical trial managers, research coordinators, raters, and psychometrists.

The lack of adequate language capability on scientific teams can be traced to several factors. Institutional hiring practices requiring bachelors or graduate degrees for certain positions that do not need that level of education can hinder hiring certain population groups. For example, despite recent gains, a 62% majority of US adults ages 25 and older do not have a bachelor's degree, including about eight‐in‐ten Latino adults (79%). 37 Second, potential Latino job applicants have had low exposure to research experience or training during their college education, thus have less knowledge and skills that they can integrate in their job search. 38 Last, there may be a prevailing belief that bilingual staff can only work with Spanish‐speaking individuals, thus being hired for only part‐time positions to justify the reduced workload assumption.

When Spanish‐speaking clinical trial staff are available, they may experience work overload, or over‐commitment to multiple research projects with recruitment goals for underrepresented groups within the same center or institution. In sum, sites without sufficient Spanish‐speaking personnel typically fall short of their recruitment goals for monolingual Spanish‐speaking Latino participants, or may recruit them in numbers that are not representative of their respective communities. 19

4.3. Language proficiency and literacy

Despite evidence that lower education is a risk factor for AD/ADRD, 39 clinical trials on AD/ADRD are not yet equipped to recruit participants with lower educational levels. This is a concern considering that the Latino population reports disproportionate rates of low literacy, including poor health literacy, especially in older groups. 40 For example, at a recent tabling event to disseminate information about a clinical trial in a Latino neighborhood in Miami, Florida, one‐third of the 220 Latino individuals who were approached were unable to read or write. Furthermore, the tendency to exclude participants with limited English‐language literacy in trials 36 could omit an estimated 28% of the US Latino population who speak mainly Spanish. 41

4.4. Competing obligations

Although prior work underscores that Latino persons have limited time to participate in clinical trials due to competing occupational, family, and social obligations, 20 clinical trial protocols typically require long, detailed, and repeated visits. For example, a study‐visit for a phase III trial can require 3 to 5 h of participants’ time to collect neuropsychiatric data, vital signs, weight, blood and urine samples, safety evaluations, infusions and post‐infusion observations. Even when a visit is short, such as a 1‐h infusion plus observation, these may occur every 2 or 4 weeks for at least 1 year. Another barrier is that most study visits are held during work hours, which may not be financially or logistically feasible. Additionally, since most research is carried out in academic centers or hospitals (not in the community in which participants reside even if the buildings are relatively close by), simply travelling to the site can pose substantial challenges.

4.5. Study partner requirements

Clinical trials in AD/ADRD usually require that a family member or friend enroll as a study partner, be present during study visits, and engage in study activities at home such as maintaining logs or managing oral study medications or devices. This level of commitment, which affects more than one person and often from the same household, will likely impose a significant burden for Latino families. Furthermore, the study partner is likely to be burdened by similar competing obligations as the trial participant. Strict protocols requiring the same study partners be available across visits also hampers individuals’ ability to make alternative arrangements to comply with visits. Issues may emerge regarding confidentiality and privacy that have not been sufficiently addressed with Latino participants. To illustrate, there is a dearth of knowledge related to attitudes and concerns of Latino close family members and other relatives of people participating as study partners or companions in AD/ADRD trials. How Latino individuals navigate personal and social stigma related to disclosure of AD/ADRD‐related genetic information, cognitive impairment, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and comorbid medical conditions remains unknown, although disclosure for stigmatized conditions such as psychiatric disorders in older Latino patients has been addressed to some degree. 42 Furthermore, some immigrant Latino family members that could be available to participate as study companions may have concerns regarding the impact that trial participation may have on their immigration status, or at least the perception of a negative effect on public charge rules. 43

4.6. Overly restrictive eligibility criteria

Trial inclusion and exclusion eligibility criteria are often established with limited consideration of common racial/ethnic‐specific factors that may prohibit participation. For example, patients with advanced disease, neuropsychiatric complications, medical comorbidities such as cerebrovascular disease, psychiatric, and substance use conditions are often excluded from participation. Other procedures such as neuroimaging and lumbar punctures may stimulate fears about injury or death emanating from these procedures. Because members of the Latino community, as well as other underrepresented groups, have higher comorbidities and serious concerns about undergoing invasive procedures, 20 these criteria become a barrier to their participation, or participation to the full extent expected by the trial sponsors and investigators.

4.7. Inadequate incentives

Study participants—including both participants and their study partners—are often not sufficiently remunerated for the personal costs needed to participate in clinical trial activities (eg, work release time, travel, and dependent care costs, submission of medical records). Furthermore, incentives are usually offered only after the participant enrolls in the trial, with incentives not given for the time spent to complete pre‐screening activities that often require visits to clinics, online research activities, among others. Similarly, expenses associated with driving (ie, gas, parking, tolls) as well as public transportation are not always reimbursed. Reimbursements to hire caregivers for respite care is seldom provided. For reimbursement, some trials require social security numbers which can be off‐putting to persons who fear scammers, are undocumented or in transition to obtaining legal status, or come from mixed immigration status families. For example, social security numbers can be required if remuneration reaches a certain monetary threshold which would entail completion of a W‐9 form or other documentation that may be perceived as voiding ineligibility (or reducing benefit amounts) for government and income‐based benefits for which they are eligible. Finally, incentives other than financial compensations such as information and referral services, care management, and resource advocacy are limited, yet could provide legitimate incentives for study participation.

4.8. Healthcare‐related barriers

Many AD/ADRD trials rely on participant referrals from primary care physicians, specialists, and other healthcare providers embedded in community clinics or academic healthcare settings. This siloed recruitment strategy has potentially negative implications for Latino clinical trial participation. First, participants who enroll in trials tend to be people whose basic healthcare needs are relatively addressed; these individuals often have better access to a regular source of medical care (ie, they have a personal doctor or healthcare provider to consult with in case of illness). The Latino population is the least likely racial/ethnic group in the US to say that they have a usual and constant source of care. Even with the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a Latino individual is still nearly three times more likely to be uninsured than a non‐Hispanic White person, and about 1 out of 5 Latino individuals have no healthcare coverage at all, 44 thus impacting trial referrals.

Second, primary care providers in the position to provide referrals to clinical trials are not incentivized to refer individuals due to lack of time, lack knowledge of available trials and specific trial details, and concerns about side effects with experimental therapies. Third, results of clinical trial exams, assessments, and imaging scans may uncover incidental findings and need for further follow‐up amid suboptimal healthcare in general, and AD/ADRD management in particular. Thus, assumptions that an optimal healthcare system exists to provide study referrals as well as receive referrals for follow‐up care are misleading, and underestimate barriers to Latino trial participation, follow‐up and retention.

Lastly, lessons learned particularly from oncology trials point to how insurance payers are billed to cover a study's standard of care components (eg, diagnosis tests, treatments, or other aspects of routine care). 45 Without such provisions, individuals without insurance would not be eligible to participate or would be billed for standard of care which may dampen or eliminate study participation altogether. Additionally, recruitment of uninsured (or underinsured) individuals creates possible ethical considerations as it can be viewed as exerting undue influence, with many IRBs and regulators instituting policies limiting this practice. 46

5. MACRO‐LEVEL BARRIERS TO LATINO REPRESENTATION IN CLINICAL AD/ADRD TRIALS

Macro‐level barriers involve state, national, and international funding and regulatory bodies that set in motion and regulate scientific, policy, organizational, and financing requirements for clinical AD/ADRD trials. Disseminating findings in academic journals and scientific meetings is also included in the macro domain. Barriers range from funding mechanisms to the racial/ethnic make‐up of key decision‐makers at the institutional level.

5.1. Criteria for reviewing and approving clinical trials funding

One barrier to Latino representation emanates from study review and approval criteria that perpetuate failed accruals of recruitment targets, namely recruitment and retention of Latino participants. As discussed above, sentinels of flawed trial design include lack of sufficient bilingual/bicultural personnel (even when the catchment area has mostly Latino residents), 47 and unclear and underfunded recruitment and retention plans/budgets. 48 Thus, this structural barrier addresses how research funders and regulatory entities approve initial funding of AD/ADRD trials with thin recruitment and retention plans/budgets, and subsequent trial funding even though awardees’ annual reports indicate failures in meeting planned enrollment goals related to Latino participation.

5.2. Criteria for disseminating of study findings

Structural barriers emerge in the reporting and dissemination of scientific findings through such venues as scientific and professional journals and scientific and conferences. Such dissemination practices act as barriers to Latino representation when reporting criteria underreport sample composition and representativeness. 49 For example, clinical trialists may not be required to disclose the detailed racial/ethnic composition of the sample when presenting at scientific conferences and publishing study findings. Relatedly, researchers are not systematically required to justify the reasons for the limited Latino representation—or that of any other underrepresented group—or they simply combine minority populations into a single group (eg, all non‐Latino White participants versus all else) including failure to report subgroup outcomes when they disseminate findings.

5.3. Criteria for approving and reimbursing treatments

Treatments can be approved by the FDA even if they have not been sufficiently tested with diverse samples, as the examples of both lecanemab and aducanumab have illustrated. 9 , 11 Lecanemab was tested in 12.4% Hispanic, and 2.3% Black participants. 45 Regarding reimbursements, aducanumab, lecanemab and other prospective FDA‐approved anti‐amyloid therapies were initially approved for reimbursement by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) only if administered in approved clinical trial settings. A recent CMS determination will allow for coverage with evidence development, which will include a variety of study designs ranging from longitudinal comparative studies to pragmatic clinical trials outside hospital‐based centers with adequate clinical expertise and infrastructure. Relying on academic research settings with a weak track record in recruiting underrepresented groups in trials, coupled with payer policies that restrict access, perpetuates the status quo of treatments benefitting primarily non‐Latino White participants.

5.4. Executive workforce

The executive workforce responsible for making funding decisions and regulatory policies has a limited representation of Latino executives. For example, at the National Institutes of Health, only 4% of executives are Latino individuals, compared to 54% non‐Latino White persons and 20% Black Americans, with Asian Americans represented at the same rate as the Latino community. 37 Furthermore, editors and editorial board members of scientific journals, who have decision‐making authority around submission guidelines describing sample characteristics and outcomes per underrepresented groups, are often not Latino. Thus, decisions related to diversity in clinical trial participation and the review process of academic journals where the science is disseminated are often made by non‐Latino executives who may or may not be cognizant of Latino representation in ADRD/AD clinical trials and the structural barriers discussed here.

5.5. Anti‐amyloid focus

Despite the recent and promising lecanemab findings with anti‐amyloid immunotherapies, 33 debate exists whether the predominant allocation of scientific resources towards anti‐amyloid targets and treatments may have hampered the elucidation of alternative factors with possible etiologic roles in preventing and treating AD/ADRD. These etiologic factors include social determinants of health (racism, 50 , 51 , 52 neighborhood characteristics, 53 education 40 ), and other novel environmental (air pollution) 54 and biologic targets (cardiovascular disease, 55 infectious agents 56 ), among others. Although the debate continues and the situation may be slowly changing, attention to diverse and novel etiologic targets is crucial and within the realm of the Latino lived experience.

Expanding these efforts is important given the limited evidence that anti‐amyloid approaches may be effective for Latino individuals. Recent findings on a sample of 17,000 participants found that, despite their elevated risks of developing AD/ADRD, Black and Latino participants presented lower odds of amyloid PET positivity compared to White participants. 5 This finding signals possible differences in the underlying etiology of cognitive impairment across racial/ethnic subgroups with implications for disease‐modifying targets that go beyond anti‐amyloid and other biomarker mechanisms. It is important to highlight that progress in AD/ADRD therapies has been based on innovations in AD biomarkers, which in turn has been based in studies with low representation of non‐White populations. One of the largest studies around amyloid brain PET, the IDEAS study, enrolled only about 4% of self‐identified Latino participants. 57

Similarly, AD biomarker research in biofluids, such as cerebrospinal fluid is impacted by negative attitudes (“fear of invasive procedure”) around lumbar punctures (“spinal tap”), which seem more prevalent in non‐White communities. 58 Understanding the prevalence and trends of positive AD biomarkers in the Latino population and their attitudes toward research procedures could be key to enhancing participation. In sum, whether we focus on diversifying the clinical trial pipeline, or diversifying the etiological foci, paying attention to multi‐level factors that disproportionately affect the Latino community including social determinants of health is key to increasing meaningfulness in trial participation.

6. CONSIDERATIONS GOING FORWARD

Before discussing recommendations in the following section, we turn our attention to specific considerations going forward to enhance the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment. Our framework thus far centers around Latino individuals in the US, thus identifying how the framework can be utilized with other groups, including across international contexts, is advisable. For example, some countries do not require racial/ethnic descriptions of their study samples, but if they register their trials in the US clinicaltrials.gov, they would be required to do so.

We acknowledge that the Latino community is diverse and is so with regards to country of origin, cultural beliefs, income and educational levels, acculturation level, regional differences, and AD/ADRD risk factors, among others. The “one‐size fits all” approach will need to be attenuated by tailoring the framework to local contexts and lived experiences. A related issue is that barriers to trial implementation and recruitment in Latin America and the Caribbean are likely different from those in the US. For example, previous work highlights the lack of available epidemiologic data, poorly standardized clinical practice and provider training, and barriers related to low‐resourced research and clinical systems, unstable economics, and stark health and income disparities. 59 , 60

Our framework is a conceptual tool to aid in enhancing Latino recruitment to AD/ADRD trials, and thus will need to be empirically tested in order to arrive at evidence‐based guidelines or best practices. Initiating quick action and having sufficient funding to put these recommendations into motion require key levers to put the framework to the test, much like what has been accomplished through the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Health Disparities Framework. 61 Recommendations can be tailored as evidence is obtained, and future research gaps and opportunities for action should be identified. It is important to note that none of the suggested levels is isolated or disconnected; each level is likely to be influenced by the next level and vice‐versa. A cross‐cutting consideration is the need to foment community‐academia‐public‐private partnerships that can facilitate the integration of the proposed multi‐level framework across these recommendations. Future efforts should address whether such requirements are sufficient or likely to be successful in increasing diversity recruitment goals.

7. ADDRESSING STRUCTURAL BARRIERS: A GLANCE AT CURRENT INITIATIVES

Our focus on barriers at the meso‐ and macro‐levels is the springboard for a series of recommendations summarized in Table 2. To develop these recommendations, we took lessons from current initiatives to increase trial representation for the Latino community and other underrepresented groups. The impetus for most initiatives stemmed from the national strategy of the NIA to increase the recruitment and participation in AD/ADRD clinical research published in the report titled “Together We Make the Difference.” 21 The report highlighted the public health priority of effectively treating AD/ADRD, drawing from data representative of all people, particularly those who experience health disparities. 17 To support this national strategy, the NIA offered funding opportunities to increase the diversity of participants in AD/ADRD research (eg, NOT‐AG‐21‐033; PAR‐18‐749).

TABLE 2.

Recommendations to enhance and secure Latino AD/ADRD clinical trial participation based on the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment.

| Recommendation | Summary | Framework dimension | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Make binding all diversity plans at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AD/ADRD clinical trials | The FDA should make it binding that all clinical trials incorporate diversity plans seeking approval to commercialize treatments. Proactive strategies to incorporate public input from diverse Latino stakeholders should be fomented on future drafts of guidance documents related to AD/ADRD clinical trials. | Macro |

| 2 | The National Institutes of Health (NIH) to continue to require robust initiatives and diversity plans for all AD/ADRD clinical trials. | The NIH and other sponsors should favor funding clinical trials with robust diversity plans. Trial sites should report on the racial/ethnic composition of their catchment area. Sites should be required to have protocols and bilingual/bicultural personnel in place to recruit Latino participants if they comprise more than 20% of the catchment area. | Macro |

| 3 | Issue a call to pharma partners (PP) and clinical research organizations (CRO) to address structural factors that inhibit Latino representation in AD/ADRD clinical trials. | The need for collaboration across all parties is paramount. Federal and state policies that incentivize PP and CRO should be developed with the goal of reducing disparities in research participation. Community‐level strategies (education, screening, preventative care, patient navigation, etc.), should be financed at robust levels, and staffing patterns reviewed to reflect Latino representation at all levels of the organization. | Macro, meso |

| 4 | Honor Latino representation throughout the design of the clinical trial | Researchers should provide evidence of study designs that are co‐designed with community partners, and respectful of Latino priorities, values, and inclusionary practices. Novel incentives should be considered and study partner criteria should be modified. Principal investigators (PIs) should consider Latino scientists in PI‐succession plans. | Meso, micro |

| 5 | Shift to—and embed operations—within Latino communities and settings | Researchers should identify ways to conduct trial visits in Latino communities and settings. Embed trial work in communities, and hire research personnel from these communities. | Meso, micro |

| 6 | Focus on Latino participants’ healthcare needs and preferences for information | Researchers should offer follow‐up healthcare services to address unmet healthcare needs and preferences of Latino participants. | Macro, meso, micro |

| 7 | Creatively address limited literacy in English and Spanish | Sponsors should support initiatives to recruit Latino participants with limited English‐ and/or Spanish‐language literacy. Researchers should stratify participants by literacy level and offer incentives to address literacy issues. | Macro, meso, micro |

| 8 | Dissemination of findings should require information on sample representativeness | Organizers of scientific conferences and journal editorial boards should require transparency of sample demographic data and encourage studies on subgroup differences, including race and ethnicity, among others. | Macro |

| 9 | Expand research initiatives to include diverse cohorts and etiologies related to cognitive health based on what matters most to the Latino community | Cross‐institutional/sectorial funding should expand our etiologic understanding of factors linked with cognitive decline and resilience among Latino people from an intersectional perspective. Trials should promote research priorities on issues that matter most to Latino participants. | Macro, meso, micro |

| 10 | Support national legislation promoting trial participation of underrepresented groups | All actors in this space should support legislative policies advancing the science of inclusion in research and clinical trials and provide technical assistance to enhance diversity (eg, the Equity in Neuroscience and Alzheimer's Clinical Trials Act) | Macro, meso |

One of these funding opportunities in the area of recruitment science sponsored the testing of a national intervention named El Consorcio (The Consortium) to accelerate Latino representation in four sites of a large clinical AD/ADRD trial (R24 AG071456: PIs Hill, Perez, Portacolone). As part of this intervention, Latino nurses from the National Association of Hispanic Nurses and local offices of the Alzheimer's Association led monthly presentations across the intervention sites in diverse Latino communities to explain the importance of clinical trials and present participation opportunities for a large AD/ADRD prevention trial. Using a two‐phase, randomized controlled trial design, we are currently testing culturally and linguistically relevant recruitment strategies across four US cities in partnership with AHEAD A3‐45 study sites with Spanish‐language personnel. Efforts are coordinated by bilingual/bicultural community outreach specialists from the community in partnership with local chapter NAHN and Alzheimer's Association leaders. Cultural‐ and linguistic training is provided by study key personnel including the authors of this paper who have expertise in community‐based intervention development, interagency collaborations, and community organizing.

The recommendations that follow (see Table 2) draw from these collective lived experiences and scientific expertise and are intended to infuse a sense of inclusion, respect, and fairness in matters related to Latino participation in AD/ADRD trials. Although our framework recognizes micro‐level strategies in Latino recruitment—and as mentioned above, all levels can interact with one another—we reserve our attention to the meso and macro domains. Important to note is that some of these recommendations may be already underway (including initiatives discussed above); thus, efforts should follow to ascertain whether they are enough, or likely to be successful over the long run.

8. RECOMMENDATIONS

8.1. Make binding all diversity plans at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AD/ADRD clinical trials

Given that the goal of most AD/ADRD clinical trials is to have their treatments approved by the FDA, the FDA has the regulatory power to increase Latino representation, as well as that of other underrepresented groups. A promising FDA initiative has been the recent dissemination of a draft guidance for industry on “diversity plans to improve enrollment of participants from underrepresented racial and ethnic populations in clinical trials.” 62 The document details the possible requirement for FDA drug approval to “specify goals for enrollment of underrepresented racial and ethnical participants,” as well as “describe in detail the operational measures that will be implemented to enroll and retain” these populations. The proposed plan asks clinical trialists to regularly discuss the status of meeting enrollment goals, as well as plans to address any inability to achieve these goals. Our recommendation is that the FDA make this plan binding by eliciting public input from diverse Latino stakeholders and investigators (in different languages and feedback formats) on future drafts of guidance documents related to AD/ADRD clinical trials. Other strategies could include providing healthcare coverage and incentives to payers to cover incentives.

8.2. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) to continue to require robust initiatives and diversity plans for all AD/ADRD clinical trials

Funders of clinical trials, such as the NIH, can use leverage to increase the representativeness of clinical trials by disseminating national strategies and funding opportunities for novel initiatives, and by enforcing specific funding requirements. Inspired by the FDA's diversity plans, 62 we recommend that the NIH continue to require diversity plans of all clinical trialists applying for funding, and continuing renewals. Such plans should detail Latino recruitment and retention efforts with robust budgets and research designs to buttress the specific aims and representation. Clinical trial sites should report on the racial/ethnic composition of their catchment area with the recommendation that if the Latino population makes up more than 20% of the catchment area, these sites should be required to have protocols and personnel in place to recruit monolingual Spanish speakers. Trials that do not meet diversity recruitment goals should be mandated to consider the advantages and disadvantages of halting the trial, and pursuing group‐specific recruitment strategies as a priority. Finally, the design of a clinical trial should integrate and honor Latino values and priorities, as discussed in a subsequent recommendation.

8.3. Issue a call to pharma partners and clinical research organizations to address structural factors that inhibit Latino representation in AD/ADRD clinical trials

Pharma partners (PP) and contract research organizations (CRO) fund and operate the lion's share of trials in the US. The need for collaboration across all parties is paramount, and how these collaborations roll out should be better articulated. We suggest that federal and state policies that incentivize PP and CRO should be developed with the goal of reducing disparities in research participation, specifically for underrepresented groups with higher risk of AD/ADRD and disease burden. Many PP already have active programs for community‐based research participation, and there may be faster trial review channels if investigators can demonstrate trial recruitment diversity. There is some evidence that strategies at the micro and meso (community) levels may converge, such as PP and CRO assisting with programmatic supports, for example, education, screening, preventative care, patient navigation, and disaster relief programs. 63 , 64 Such community‐building assets should be optimized on a larger scale across most PP and CRO.

8.4. Honor Latino representation throughout the design of the clinical trial

We recommend that components of funding applications for clinical trials give evidence of investigators’ efforts in co‐designing studies based on Latino values, priorities, and inclusionary practices. The overall vision is to make the site of the clinical trial a haven for Latino communities—a place where they feel welcome, heard, and supported. With regards to specific components, principal investigators (PIs) need to ensure Latino bilingual/bicultural representation at all levels of their proposals, ranging from co‐PIs and other key personnel, to members of advisory boards, with at least the proportion of such staff reflecting the proportion of Latino participants to be recruited in the study, and/or local community. Second, budget line items need to be specifically appropriated for robust and diverse outreach activities. Protocols should make participating in clinical trials an attractive opportunity, and at times evocative of a festive event (una fiesta) with opportunities to engage in routine health screening, and informational activities regarding community resources, rather than dry lectures on how “Latino individuals are at‐risk for dementia.” For example, our group found that Latino outreach participants welcomed bilingual health screenings (eg, blood exams, eye checks), and community resource sharing as incentives. 20 We reiterate the need to reimburse caregiving activities or respite care, and restricting strict rules for enrollment of a single study partner by allowing different study partners, if available.

For PIs, especially who those with a long and robust record of funding and scientific expertise, we recommend that they take the time to engage in self‐reflection of their own cultural humility and cultural competence, to ensure that they can effectively lead the proposed research effort with a Latino focus. In the absence of the ability to lead the clinical trial in this spirit, PIs should consider initiating a succession plan to promote Latino scientists to take the lead with significant career support and technical assistance to ensure their success on behalf of Latino people engaging with the research enterprise.

8.5. Shift to—and embed operations—within Latino communities and settings

We recommend that the research activities and affiliated workforce blend with the local community by partnering with local small and large businesses, ethnic healthcare organizations, places of worship, naturally‐occurring groups, Latino‐serving non‐profits, etc. Hiring preferences should include representatives from the local Latino communities with robust onboarding and training sessions in clinical trial designs. Although the perception of the academic clinical site as an “ivory tower” has been documented in Black communities, 65 it is nevertheless important for clinical trialists to open the doors and “be present” in Latino communities. An advantage of embedding the trial in local communities is that—when visits to academic trials sites are necessary—participants and study partners will have already had the exposure to clinical staff, thus increasing the quality of interpersonal interactions (personalismo).

8.6. Focus on Latino participants’ healthcare needs and preferences for information

Consistent with other studies focused on increasing recruitment of historically excluded communities in clinical research, addressing healthcare‐related barriers requires “meeting people where they are.” 66 For Latino individuals, more effective outreach should consider the inclusion and support of trusted organizations and local leaders known to families such as local politicians, social workers, teachers, healthcare providers, immigrant advocates, and community health workers (promotoras), among others. There are unique differences across Latino communities; therefore, it is important to understand where most Latino individuals in their respective communities obtain health and healthcare‐related information, for example, through local schools, faith‐based organizations, mutual aid societies, monolingual social media and radio programs, and so on. Furthermore, it would be necessary and ethical to offer follow‐up healthcare services to participants that have incidental findings or other health and social needs but lack health insurance coverage, or optimal care in general.

8.7. Creatively address limited literacy in English and Spanish

Considering that Latino individuals with limited Spanish or English literacy are at elevated risk of developing AD/ADRD, we recommend prioritizing and funding the development of innovative strategies that enhance clinical trial participation by modifying trial protocols, recruitment and information materials, communication processes, and so on, to sixth‐grade education levels (without infantilizing messaging or images). We also encourage studies comparing outcomes according to Latino participants’ level and type of literacy (reading, writing, numerical, digital, etc.). Furthermore, building on our vision of clinics as welcoming havens, researchers could provide incentives such as free tutoring on reading and writing in Spanish and English, career and occupational advancement workshops, mentoring opportunities, and intergenerational strategies to accelerate health literacy on AD/ADRD. Although we place emphasis on English and Spanish, we acknowledge that other languages may emerge as salient, such as indigenous languages and dialects.

8.8. Dissemination of findings should require information on sample representativeness

Organizers of scientific meetings and conferences and editors of peer‐reviewed journals should stipulate in their submission guidelines the requirement of providing data on racial/ethnic composition of samples and justifications if samples are not representative. Furthermore, rather than focusing exclusively on main effects, researchers should be encouraged to publish subgroup differences across race and ethnicity, nativity, gender, and other characteristics such as language. Qualitative studies that elucidate reasons and key levers to accelerate Latino research engagement and satisfaction with study participation should be strongly encouraged. Future calls for papers and conference themes should request submissions that apply the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment.

8.9. Expand research initiatives to include diverse cohorts and etiologies related to cognitive health based on what matters most to Latino participants

We recommend robust cross‐institutional funding initiatives of AD/ADRD trials that expand etiologic perspectives of high salience to Latino participants. Funding goals for Latino‐specific AD/ADRD trials should focus on diversifying trial cohorts and diversifying the putative etiologies linked to the spectrum of AD/ADRD. Priority setting of funding initiatives and selection of project awards should be co‐designed with Latino people, lay and professional providers that serve them, as well as Latino‐serving ethnic organizations and mutual aid groups with a longstanding tradition in the community.

In tandem with Latino values of respeto (respect) and familismo (familism), funding opportunities must go beyond deficit‐centered hypotheses and include strengths‐based constructs that honor sources of resilience (cognitive, social, community, faith‐based, organizational, etc.) and new ways to address large‐scale social determinants of health such as socioeconomic conditions, occupation, neighborhood environment, racial and ethnic discrimination, and immigration. These foci can be enhanced with an intersectional health equity perspective by examining outcomes across nativity, language, regional subgroups, gender identity and sexual orientation, among many others. Therefore, diversifying trial cohorts and elucidating multiple factors (including within group differences) that accelerate or decelerate cognitive decline in Latino individuals, will need to rely on more synergistic ways of knowing across micro‐meso‐macro systems.

8.10. Support national legislation promoting trial participation of underrepresented groups

We recommend that researchers and funders act to develop and approve legislative bills aimed at increasing Latino participation, as well as that other underrepresented groups, in AD/ADRD trials. A promising bill under consideration is the bipartisan Equity in Neuroscience and Alzheimer's Clinical Trials (ENACT) Act, which—if approved—would expand education and outreach to underrepresented populations, encourage the diversity of clinical trial staff, and reduce participation burden. The act would provide funding for the NIA to expand the number of Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers in areas with higher concentrations of underrepresented populations. The act earmarks additional funding for Research Centers on Minority Aging Research to increase education and outreach to underrepresented communities and primary care physicians, as well as increase knowledge about trial participation and the disparate impact of AD/ADRD on underrepresented groups. The act would also direct the NIA to enhance the diversity of PIs and study staff conducting clinical trials for AD/ADRD so they are more representative of the populations they seek to enroll.

9. CONCLUSION

Clinical trials will one day lead our nation towards finding a cure or prevention for AD/ADRD, thereby eliminating the human and societal toll—a benefit that should be equally and equitably distributed across population groups. Our goal is to accelerate the representation of the Latino population and other underrepresented groups in AD/ADRD trials—and doing so with clear guidelines and bold strategies that respect people's lived experience. Inclusion of Latino participants in AD/ADRD research provides opportunities to ensure fairness and equity in AD/ADRD trials, close the racial and ethnic disparity gap in diagnosis, treatment, and care, and optimize “good science.” Given demographic and health‐related trends, optimizing the health of the Latino community is good not only for its members, but also for our nation as a whole. Although the framework is applied to the US Latino population, our call to action embraces the lived experience of all people who experience ADRD disparities. Future work should test the application of the Micro‐Meso‐Macro Framework for Diversifying AD/ADRD Trial Recruitment to structural recruitment and retention barriers in AD/ADRD research and clinical trials.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

J.C.R. is a site PI for clinical trials sponsored by Eli Lilly and Eisai and receives research support from NIA/NIH K23AG059888. C.V.H. and Y.R. are full‐time employees of the Alzheimer's Association. All other authors report they have nothing to disclose. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Obtaining consent was not necessary for this work.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

María P. Aranda, David X. Marquez, Dolores Gallagher‐Thompson, Adriana Pérez, Julio C. Rojas, and Elena Portacolone were funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R24 AG071456. María P. Aranda was funded by U54AG063546 which funds NIA Imbedded Pragmatic Alzheimer's Disease and AD‐Related Dementias Clinical Trials Collaboratory (NIA IMPACT Collaboratory), as well as P30AG066530, and P30AG043073. Julio C. Rojas was funded by NIH/NIA K23AG59888. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Funding for this work was provided by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) of the National Institutes of Health under award number R24 AG071456.

Aranda MP, Marquez DX, Gallagher‐Thompson D, et al. A call to address structural barriers to Hispanic/Latino representation in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: A micro‐meso‐macro perspective. Alzheimer's Dement. 2023;9:e12389. 10.1002/trc2.12389

[Correction added on 20 July 2023, after first online publication: The spelling of the name of the author Elena Portacolone was corrected.]

REFERENCES

- 1. Maria Del Rio‐Gonzalez A. To Latinx or Not to Latinx: a question of gender inclusivity versus gender neutrality. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(6):1018‐1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krogstad J, Passel J, Noe‐Bustamante L. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Pew Research; 2022;2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aranda MP, Kremer IN, Hinton L, et al. Impact of dementia: health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(7):1774‐1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu S, Vega W, Resendez J, Jin HP. Projection of the Costs for U.S. Latinos Living with Alzheimer's Disease Through 2060 . 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilkins CH, Windon CC, Dilworth‐Anderson P, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in amyloid pet positivity in individuals with mild cognitive impairment or dementia: a secondary analysis of the imaging dementia‐evidence for amyloid scanning (IDEAS) cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1139‐1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hinton L, Haan M, Geller S, Mungas D. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Latino elders with dementia or cognitive impairment without dementia and factors that modify their association with caregiver depression. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):669‐677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Quiroz YT, Solis M, Aranda MP, et al. Addressing the disparities in dementia risk, early detection and care in Latino populations: highlights from the second Latinos & Alzheimer's Symposium. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(9):1677‐1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Watson JL, Ryan L, Silverberg N, Cahan V, Bernard MA. Obstacles and opportunities in Alzheimer's clinical trial recruitment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):574‐579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manly JJ, Glymour MM. What the aducanumab approval reveals about alzheimer disease research. JAMA Neurol. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raman R, Quiroz YT, Langford O, et al. Disparities by race and ethnicity among adults recruited for a preclinical Alzheimer disease trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2114364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):322‐333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):311‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ostrowitzki S, Lasser RA, Dorflinger E, et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, et al. Trial of Solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):321‐330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mintun MA, Lo AC, Duggan Evans C, et al. Donanemab in early Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(18):1691‐1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Budd Haeberlein S, Aisen PS, Barkhof F, et al. Two randomized phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer's disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):197‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Langbaum JB, Zissimopoulos J, Au R, et al. Recommendations to address key recruitment challenges of Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19(2):696‐707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gutierrez A, Cain R, Nadine D, Aranda MP. The digital divide exacerbates disparities in Latinx recruitment for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias online education during COVID‐19. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2022;8:23337214221081372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marquez DX, Perez A, Johnson JK, et al. Increasing engagement of Hispanics/Latinos in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1):e12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elliott CL. Together we make the difference: national strategy for recruitment and participation in Alzheimer's and related dementias clinical research. Ethn Dis. 2020;30(Suppl 2):705‐708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Check Hayden E. Racial bias continues to haunt NIH grants. Nature. 2015;527(7578):286‐287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quinones AR, Mitchell SL, Jackson JD, et al. Achieving health equity in embedded pragmatic trials for people living with dementia and their family caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(Suppl 2):S8‐S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dilworth‐Anderson P, Cohen MD. Beyond diversity to inclusion: recruitment and retention of diverse groups in Alzheimer research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(Suppl 1):S14‐S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aranda MP. Racial and ethnic factors in dementia care‐giving research in the US. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5(Suppl 1):S116‐S123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bilbrey AC, Humber MB, Plowey ED, et al. The impact of Latino values and cultural beliefs on brain donation: results of a pilot study to develop culturally appropriate materials and methods to increase rates of brain donation in this under‐studied patient group. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(3):237‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tonelli MR. Integrating evidence into clinical practice: an alternative to evidence‐based approaches. J Eval Clin Pract. 2006;12(3):248‐256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tonelli MR, Shapiro D. Experiential knowledge in clinical medicine: use and justification. Theor Med Bioeth. 2020;41(2‐3):67‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gallagher‐Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Arean P. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aranda M. Cultural issues and Alzheimer's disease: Lessons from the Latino community. Geriatric Care Management Journal. 1999;9:13‐18. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Villa V, Wallace S. Latinos and Dementia: Prescriptions for Policy and Programs that Empower Older Latinos and Their Families . 2020.

- 32. Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):216‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gray HL, Jimenez DE, Cucciare MA, Tong HQ, Gallagher‐Thompson D. Ethnic differences in beliefs regarding Alzheimer disease among dementia family caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(11):925‐933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chavez‐Dueñas N, Adames H, Perez‐Chavez J, Smith S. Contextual, Cultural, and Sociopolitical Issues in Caring for Latinxs with Dementia: When the Mind Forgets and the Heart Remembers . 2020.

- 35. Jaldin MA, Balbim GM, Colin SJ, et al. The influence of Latino cultural values on the perceived caregiver role of family members with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Ethn Health. 2022:1‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Massett HA, Mitchell AK, Alley L, et al. Facilitators, challenges, and messaging strategies for Hispanic/Latino populations participating in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias clinical research: a literature review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;82(1):107‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mora L. Hispanic Enrollment Reaches New High at Four‐year Colleges in the U.S., But Affordability Remains an Obstacle. Pew Research Center; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pierszalowski S, Bouwma‐Gearhart J, Marlow L. A systematic review of barriers to accessing undergraduate research for STEM students: problematizing under‐researched factors for students of color. Social Sciences. 2021;10(9):328. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Litke R, Garcharna LC, Jiwani S, Neugroschl J. Modifiable risk factors in Alzheimer disease and related dementias: a review. Clinical therapeutics. 2021;43(6):953‐965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sisco S, Gross AL, Shih RA, et al. The role of early‐life educational quality and literacy in explaining racial disparities in cognition in late life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(4):557‐567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pew Research Center . A Brief Statistical Portrait of U.S. Hispanics. Pew Research Center; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fuentes D, Aranda MP. Disclosing psychiatric diagnosis to close others: a cultural framework based on older Latin@s participating in a depression trial in Los Angeles county. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(11):1595‐1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Department of Homeland Security . Public charge ground of inadmissibility . Federal Register; 2022;2022. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baumgartner J, Collins S, Radley D, Hayes S. How the Affordable Care Act Has Narrowed Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Health Care. The Commonwealth Fund; 2020.

- 45. Obeng‐Gyasi S, Kircher SM, Lipking KP, et al. Oncology clinical trials and insurance coverage: an update in a tenuous insurance landscape. Cancer. 2019;125(20):3488‐3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cho HL, Danis M, Grady C. The ethics of uninsured participants accessing healthcare in biomedical research: a literature review. Clin Trials. 2018;15(5):509‐521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Suarez‐Morales L, Matthews J, Martino S, et al. Issues in designing and implementing a Spanish‐language multi‐site clinical trial. Am J Addict. 2007;16(3):206‐215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Han SH, Massett HA, Shakur M, Lockett J, Mitchell AK. Analysis of recruitment planning for under‐represented participants in NIA‐funded Alzheimer's disease and Alzheimer's disease related dementias clinical trials. Alzheimer's Association International Conference; 2021; Alzheimer's & Dementia.

- 49. Canevelli M, Bruno G, Grande G, et al. Race reporting and disparities in clinical trials on Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tom SE, Phadke M, Hubbard RA, Crane PK, Stern Y, Larson EB. Association of demographic and early‐life socioeconomic factors by birth cohort with dementia incidence among us adults born between 1893 and 1949. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2011094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coogan P, Schon K, Li S, Cozier Y, Bethea T, Rosenberg L. Experiences of racism and subjective cognitive function in African American women. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lin PJ, Emerson J, Faul JD, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in knowledge about one's dementia status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1763‐1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Powell WR, Buckingham WR, Larson JL, et al. Association of neighborhood‐level disadvantage with Alzheimer disease neuropathology. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abolhasani E, Hachinski V, Ghazaleh N, Azarpazhooh MR, Mokhber N, Martin J. Air pollution and incidence of dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Neurology. 2023;100(2):e242‐e254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):143‐152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wozniak MA, Mee AP, Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA is located within Alzheimer's disease amyloid plaques. J Pathol. 2009;217(1):131‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rabinovici GD, Gatsonis C, Apgar C, et al. Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with subsequent change in clinical management among Medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1286‐1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Blazel MM, Lazar KK, Van Hulle CA, et al. Factors associated with lumbar puncture participation in Alzheimer's disease research. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;77(4):1559‐1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ibanez A, Pina‐Escudero SD, Possin KL, et al. Dementia caregiving across Latin America and the Caribbean and brain health diplomacy. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2(4):e222‐e231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parra MA, Baez S, Allegri R, et al. Dementia in Latin America: assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology. 2018;90(5):222‐231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hill CV, Perez‐Stable EJ, Anderson NA, Bernard MA. The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research Framework. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):245‐254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Food and Drug Administration . Diversity Plans to Improve Enrollment of Participants from Underrepresented Racial and Ethnic Populations in Clinical Trials Guidance for Industry . 2022.

- 63. Novartis . Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation embarks on Alzheimer's disease educational effort for the U.S. Hispanic community . 2012;. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lilly. Community engagement .

- 65. Wasserman J, Flannery MA, Clair JM. Raising the ivory tower: the production of knowledge and distrust of medicine among African Americans. Journal of medical ethics. 2007;33(3):177‐180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cunningham‐Erves J, Joosten Y, Kusnoor SV, et al. A community‐informed recruitment plan template to increase recruitment of racial and ethnic groups historically excluded and underrepresented in clinical research. Contemporary clinical trials. 2023;125:107064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information