Abstract

Objective

The closure of schools and other educational institutes around the world has been one of the consequences of the COVID-19 and has resulted in online teaching. To facilitate online teaching, there has been an increase in the use of smartphones and tablets among adolescents. However, such enhancement in technology use may put many adolescents at the risk of problematic use of social media. Consequently, the present study explored the direct relationship of psychological distress with social media addiction. The relationship between the two was also assessed indirectly via the fear of missing out (FoMO) and boredom proneness.

Methods

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted with 505 Indian adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, studying in grades 7 to 12. Standardized tools (with some modifications to suit the context of the present study) were used to collect data.

Results

The results showed significant positive associations between psychological distress, social media addiction, FoMO, and boredom proneness. Psychological distress was found to be a significant predictor of social media addiction. Moreover, FoMO and boredom proneness partially mediated the relationships between psychological distress and social media addiction.

Discussion

The present study is the first to provide evidence for the specific pathways of FoMO and boredom proneness in the relationships between psychological distress and social media addiction.

Keywords: Psychological distress, Social media addiction, Fear of missing out, Boredom proneness

Introduction

The closure of schools and other educational institutes around the world has been one of the most noticeable consequences of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Such measures were implemented because physical distancing is considered one of the most effective ways to contain the spread of the virus (Abel & McQueen, 2020). Hence, most activities transitioned from offline to online mode including online learning (Camargo et al., 2020) which despite offering some irrefutable advantages (Almahasees et al., 2021) also increased the use of technological devices like smartphones and tablets. Parents, who generally never allowed their children to use smartphones, may have felt forced to buy them for their children due to the introduction of online classes (Teja, 2020). Some adolescents spent around 5–6 h daily attending online classes (Nigam, 2020), and some teachers prohibited adolescents from turning off their cameras or leaving early during class (Kelly, 2020).

Despite disparities in access to digital technologies, young adults’ mobile devices are often the primary channels to access social media (Villanti et al., 2017). Moreover, increased activity on social media during the pandemic has been reported (Karhu et al., 2021). In general, social media use has both positive and negative consequences for adolescents. For instance, social media use has been associated with many positive psychological outcomes, such as building social capital (Green-Hamann et al., 2011), enhancing self-esteem (Best et al., 2014), and connecting with others (Sheldon et al., 2011). However, excessive use may sometimes culminate in problematic use and may even result in social media addiction (e.g., Ryan et al., 2014). Social media addiction has been associated with a variety of negative psychological outcomes including an increase in negative affect, lower levels of self-esteem, and reduced relationship quality, as well as increased suicidal ideation and actual suicide among adolescents (Shannon et al., 2022). Despite the undeniable positive role that social media played in the unprecedented situation of the pandemic (Wiederhold, 2020), it has also been reported that COVID-19-related stress is associated with social media addiction (Zhao & Zhou, 2021).

Despite not being recognized as a legitimate addiction under the current psychiatric classification systems of the DSM-5 and ICD-11, social media addiction has gained substantial research attention due to its detrimental impact on different domains of interpersonal and intrapersonal functioning (Yu et al., 2018; Zheng & Lee, 2016). Addiction is viewed as an excessive focus on social media activities that are manifested as substantial time and effort being devoted to social media leading to consequent withdrawal from other important daily activities (e.g., occupation, education, and/or relationships) and adverse mental health consequences (Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014; Andreassen, 2015). The conceptualization of social media addiction has varied greatly to include spending excessive time on social media (Can & Kaya, 2016), users’ psychological dependence on social media (Gong et al., 2020), emotional and functional attachment to the platform (Cao et al., 2020), irrational and excessive use that is detrimental to the daily life of the user (Griffiths, 2012), or simply manifested as core symptoms of addiction including salience, conflict, withdrawal, reinstatement, and relapse (Gong et al., 2020). In the present paper, “social media addiction” is used as an umbrella term to describe the totality of the problematic behavior related to social media use.

Psychological Distress and Social Media Addiction

Psychological distress has often been conceptualized as an affective state characterized by symptoms of anxiety and depression (Drapeau et al., 2012). Social media use has been an instrumental way of coping with distress (Van den Eijnden et al., 2016). Moderate use of social media has been looked at as an effective way of alleviating anxiety during the pandemic (Wiederhold, 2020). However, Huang et al. (2021) reported that negative emotions such as anxiety, stress, and depression significantly predict social media addiction. For depressed individuals, excessive social media interactions often stem from their need for validation through likes and followers (Hartanto et al., 2021). Additionally, Vannucci et al., (2017) reported that anxious Internet users tend to be more engaged with social media to mitigate their state of anxiety.

Adolescents with high levels of psychological distress and poor mental health are greater users of social media (Sampasa-Kanyinga & Lewis, 2015). In the context of COVID-19, children who reported higher psychological distress during the pandemic spent longer time on Internet-related activities (Chen et al., 2021). Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adults who had higher rates of anxiety reported higher use of social media (Drouin et al., 2020). Consequently, studies have highlighted a positive association between COVID-19-related distress and addictive social media use (Panno et al., 2020; Zhao & Zhou, 2021).

Fear of Missing Out, Boredom Proneness, Psychological Distress, and Social Media Addiction

Fear of missing out (FoMO) is a pervasive phenomenon to stay continually updated coupled with the apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which an individual is absent (Przybylski et al., 2013). FoMO in the context of social media users involves a preoccupation with the prospect that they have missed connecting and communicating with others when they are unable to get online (Alutaybi et al., 2019). FoMO has been positively associated with social media use generally (Przybylski et al., 2013), as well as social media addiction more specifically (Blackwell et al., 2017).

Depression, anxiety, and psychological distress are generally associated with social media addiction (e.g., Hartanto et al., 2021; Panno et al., 2020). However, the relationship between anxiety, depression, and stress (together referred to as “negative affectivity”) and FoMO is far from conclusive (Elhai et al., 2020b). For example, Elhai et al. (2020b) reported FoMO as the driving factor for negative affectivity, but there is also evidence that negative affectivity leads to FoMO (Wegmann et al., 2017). According to Elhai et al. (2020b), FoMO can be a natural consequence of anxiety and depression because both can lead to social isolation, which can lead to social media addiction. There is also evidence that FoMO mediates the relationship between psychopathological symptoms and problematic Internet use and smartphone use (e.g., Elhai et al., 2020a). Therefore, FoMO may be one of the mechanisms/pathways between anxiety/depression/distress and social media addiction (Elhai et al., 2020b; Oberst et al., 2017).

Boredom proneness refers to attentional and impulse control difficulties leading to experiencing boredom, which generally involves negative affect (Struk et al., 2017). Boredom proneness is positively associated with anxiety and depression (e.g., Elhai et al., 2018; Y. Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, negative affect such as depression and anxiety are conceptualized as primary causes of experiencing boredom (Eastwood et al., 2012). Boredom proneness has been positively associated with problematic Internet use (e.g., Lin et al., 2009), smartphone addiction (Wang et al., 2020), and binge drinking and drug use (Biolcati et al., 2018). Moreover, boredom-prone individuals are likely to be poor decision-makers (Yakobi et al., 2021). Boredom has been reported to mediate the relationship between social media usage and subjective wellbeing (Bai et al., 2021). It also appears to play a role in the development of problematic social media usage (Billieux et al., 2015; Elhai et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019).

The mediating role of boredom proneness has recently been explored in the context of problematic smartphone use. For example, boredom proneness has been reported to mediate the relationship between depressive/anxious symptoms with problematic smartphone use and Internet use (Elhai et al., 2018; Wegmann et al., 2018). Wang et al. (2022) found that boredom proneness mediated the relationship between the severity of depression and problematic smartphone use. Moreover, boredom proneness and FoMO were found to mediate the relationships between psychopathological symptoms such as depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use severity (Wolniewicz et al., 2020). These studies highlighted the mediating role of FoMO and boredom proneness between depression/anxiety/distress and problematic smartphone use. To the best of the present author’s knowledge, these relationships have not been explored in the context of social media addiction.

Theoretical Underpinnings and Hypothesis Development

One of the approaches to understanding social media addiction is the compensatory model, which was originally developed in the context of Internet addiction (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). This model states that negative emotions (such as anxiety, depression, and psychological distress) are the driving factors for excessive Internet use (social media use in the context of the present study). Individuals use the Internet (e.g., social media) to eliminate negative emotional states. However, when used excessively, Internet/social media use can further result in problematic social media use. Therefore, excessive social media use is viewed as an escapist coping strategy used to avoid and/or remove negative emotions and affect. This is relevant particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic because it appears to have increased anxiety, depression, and psychological distress among many individuals (e.g., de Pablo et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020) which may have consequently enhanced social media usage as a coping strategy (Singh et al., 2020) to deal with the negative affect. While it is valuable to study the direct associations between psychological distress and social media addiction, the compensatory model also emphasizes the importance of mediation and interaction effects (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014).

The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model is another theoretical framework that can also be used to understand social media addiction (Brand et al., 2016). Although it was also developed for explaining Internet addiction, it appears to be a comprehensive model because it differentiates between specific predisposing factors and moderating/mediating variables which would ultimately lead to social media addiction. Personal factors such as genetic and biological influences, personality, psychopathology, cognitions, and Internet-related motives are some of the specific predisposing factors. Coping styles and Internet-related cognitive biases can be conceptualized as moderating variables or mediating variables which might influence the relationship between predisposing factors and social media addiction (Wegmann et al., 2017).

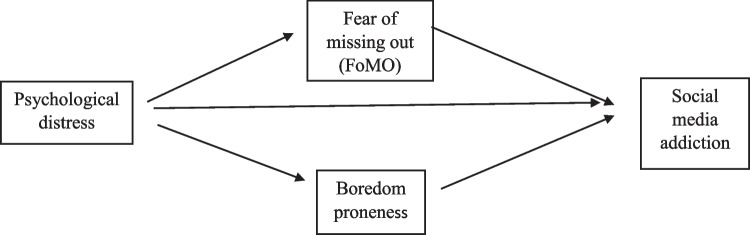

The present study examined the compensatory model and the I-PACE model in the context of social media addiction. In the present study, it was hypothesized that psychological distress would influence social media addiction. Moreover, it was also hypothesized that boredom proneness and FoMO might be possible mediators between psychological distress and social media addiction. Although the mediation pathways have been explored previously (Zhao & Zhou, 2021; Liang et al., 2022), the mechanisms through which depression, anxiety, and psychological distress influence social media addiction need to be further investigated (Vidal et al., 2020). Similar concerns have been raised by Wang et al. (2022), and they recommended studying more contemporary constructs to uncover the mechanisms involved in the development of social media addiction, beyond simply examining depression and anxiety. Therefore, in the present study, FoMO and boredom proneness were considered as mediator variables (neither of which have been explored previously to the best of our knowledge). Psychological distress was the predictor, and social media addiction was considered as an outcome variable. The proposed model is presented below in Fig. 1, and specific hypotheses (Hs) are mentioned next.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual model

Based on the aforementioned literature, eight hypotheses (Hs) were formulated. More specifically, it was hypothesized that (i) there would be an increase in time spent on social media during COVID-19 pandemic (H1); (ii) psychological distress would predict social media addiction (H2); (iii) psychological distress would predict FoMO (H3); (iv) FoMO would predict social media addiction (H4); (v) psychological distress would predict boredom proneness (H5); boredom proneness would predict social media addiction (H6); FOMO would mediate the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction (H7); and boredom proneness would mediate the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction (H8).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted with 505 Indian adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, studying in grades 7 to 12. Of these, 127 (25%) belonged to nuclear families (children living with their parents), while 380 were from joint families (75%) (children living with parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins). Moreover, at the time of data collection, 157 participants were living under lockdown conditions (31%), while the remaining 350 were not living under mandatory lockdown conditions. A convenience sampling technique was used to collect data online utilizing the Google Forms platform. The forms were distributed on social media platforms through WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook. The participants were requested to circulate the forms among their friends and family members. The mean age of the adolescents was 14 years (SD = 1). The sample comprised of 45% males and 55% females studying in grades 7 to 12 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and social media use of the participants (N = 505)

| Variables | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of hours spent daily on social media before COVID-19 | None | 87 (17%) |

| Less than half hour | 194 (39%) | |

| 1 h | 140 (28%) | |

| 2–3 h | 70 (14%) | |

| 4–5 h | 11 (2%) | |

| More than 6 h | 3 (-) | |

| No. of hours spent daily on social media during COVID-19 | None | 54 (11%) |

| Less than half hour | 99 (20%) | |

| 1 h | 130 (26%) | |

| 2–3 h | 138 (27%) | |

| 4–5 h | 58 (11%) | |

| More than 6 h | 26 (5%) | |

| Gender | Male | 229 (45%) |

| Female | 276 (55%) | |

| Have you bought smartphones/tablets specifically for attending online classes during lockdown? |

159 (yes) 346 (no) |

31% (yes) 69% (no) |

| Social media use |

At risk for social media addiction Not at risk for social media addiction |

19 (3.8%) 486 (96.2%) |

Measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4)

The four-item PHQ-4 (Kroenke et al., 2009) assesses psychological distress. It comprises a two-item depression subscale (PHQ-2) and a two-item anxiety subscale (GAD-2). The scoring can be done separately for anxiety and depression, and can be combined to get overall score on psychological distress. Items (e.g., “How often you have been feeling nervous, anxious or on edge?”) are scored on a four-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), and a higher score indicates greater psychological distress. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Trait-State Fear of Missing Out Scale (T-SFoMOS)

There are 12 items in T-SFoMOS (Wegmann et al., 2017). Five items assess trait FoMO, and the remaining seven items assess state FoMO. Given the context of the present study (FoMO being treated as the mediating variable), only seven state items of the T-SFoMOS were used to assess state FoMO. Items (e.g., “I am continuously online in order not to miss out on anything”) are rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all true of me) to 5 (extremely true of me), and a higher score indicates higher presence of FoMO. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.84.

Short Boredom Proneness Scale (SBPS)

Four items of the SBPS (Struk et al., 2017) were used to assess boredom proneness. Items (e.g., “Many things I have to do (such as online classes) are repetitive and monotonous” and “Much of the time just sit around doing nothing”) are rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and a higher score indicates greater boredom proneness. Although the SBPS is an eight-item scale, only four items which were more relevant were used (COVID-19-related closure of school and online classes) for the present study. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha was 0.73.

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS)

The six-item Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) was used to assess the social media addiction (Andreassen et al., 2012). Items (e.g., “How often over the past year have you spent a lot of time thinking about social media or planned use of social media?”) are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very rarely) to 5 (very often). The scores range from 6 to 30, and a higher score on the BSMAS indicates a greater risk of social media addiction. Recently, a cut-off of 24 has been suggested to identify those most at risk of social media addiction (Luo et al., 2021; Stănculescu, 2022). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Faculty of Social Sciences, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India. Ethical standards in the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki were followed. They were informed about the purpose of the study, and informed consent was obtained from both the participants and their parents. They were further assured about the anonymity and confidentiality of the data. Participants were informed about the research outcomes and were told they could withdraw their data at any time.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was carried out using SPSS 21. Percentages and chi-square tests were conducted to check whether there was a significant increase in social media addiction during the pandemic. SmartPLS version 3 was used to assess the direct effect of psychological distress on social media addiction. Moreover, the mediating effect of FoMO and boredom proneness between the psychological distress and social media addiction was also examined through SmartPLS version 3. To check the significance of paths (hypothesized relationships between the predictor, outcome variable, and the mediators), path coefficients were transformed into t-statistics using bootstrapping of 5000 sample. The significance values for all the obtained results were tested at p < 0.05.

Results

As shown in Table 1, most adolescents say they spent either less than half an hour (39%) or 1 h a day on social media (28%) before the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, most adolescents said they spent 2–3 h a day on social media (27%). Before the pandemic, 2% of adolescents said they spent 4–5 h a day on social media. During the pandemic, this figure increased to 11%. In addition, before the pandemic, less than 1% of adolescents said they spent more than 6 h a day on social media. During the pandemic, this figure increased to 5%. These findings indicate that social media use among adolescents increased during the pandemic and supported H1. The difference between the number of hours spent on social media before COVID-19 and during COVID-19 was statistically significant (c2 = 293.14, p < 0.001). It was also found that 159 out of total 505 participants in the present study (31%) had smartphones and/or tablets bought for them specifically to attend online classes during the COVID-19-related lockdown and consequent school closures.

The mean score on T-SFoMOS was found to be 15.33 out of 35 (SD = 6.62) indicating a low mean value. The mean score on the BSMAS was 12.80 out of 30 (SD = 5.84) and on PHQ-4 was 3.84 out of 12 (SD = 3.34). These mean values show that social media addiction and psychological distress were found to be low in the present sample. However, the boredom proneness was found to be in the average category as the mean score was 14.84 out of 28 (SD = 6.03). The results also indicated that 3.8% were at risk of social media addiction using a cut-off of 24 (out of 30) on the BSMAS. Table 2 also shows the correlations between the variables. There was a positive correlation between psychological distress and social media addiction (r = 0.59). There were also positive correlations between distress and FoMO (r = 0.46), distress and boredom proneness (r = 0.59), FoMO and social media addiction (r = 0.54), and between boredom proneness and social media addiction (r = 0.55).

Table 2.

Mean, standard deviation, and correlations between variables

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fear of missing out | 15.33 | 6.62 | 1 | |||

| 2. Social media addiction | 12.80 | 5.84 | .54** | 1 | ||

| 3. Boredom proneness | 14.48 | 6.03 | .42** | .55** | 1 | |

| 4. Psychological distress | 3.84 | 3.34 | .46** | .59** | .59** | 1 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

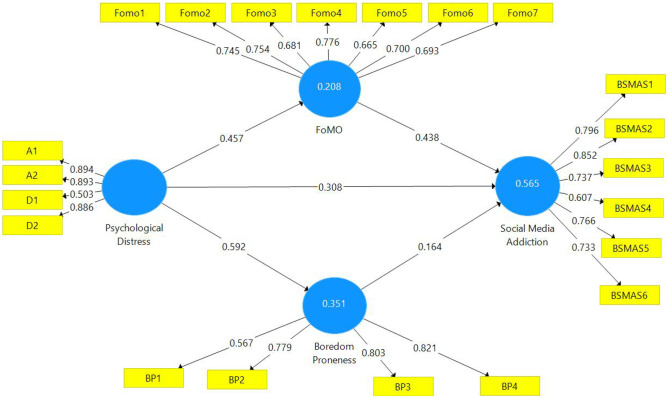

Figure 2 shows the direct influence of psychological distress (as predictor variable) on social media addiction (as the outcome variable). Figure 2 also depicts the indirect effect of FoMO and boredom proneness (as mediating variables) between the two. Psychological distress, FoMO, and boredom proneness explained 56.5% of the variance in social media addiction (p < 0.001), implying large effect size. Psychological distress explained 20.8% of the variance in FoMO (p < 0.001), implying large effect size. Psychological distress explained 35.1% of the variance in boredom proneness (p < 0.001), suggesting large effect size.

Fig. 2.

Showing direct influence of psychological distress on social media addiction, as well indirectly through fear of missing out (FoMO), and boredom proneness. A1, A2, D1, and D2 represent two items each for anxiety and depression scale respectively of psychological distress

Table 3 shows the outcome of the hypotheses testing. The results showed that psychological distress significantly predicted social media addiction (H2: β = 0.308, t = 6.63, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.133). The results also showed that psychological distress significantly predicted FoMO (H3: β = 0.457, t = 11.798, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.263) and boredom proneness (H5: β = 0.592, t = 19.790, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.541). Moreover, both FoMO (H4: β = 0.438, t = 10.680, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.321) and boredom proneness (H6: β = 0.164, t = 3.770, p < 0.001, f2 = 0.037) significantly predicted social media addiction. All the effect sizes were moderate to large except between boredom proneness and social media addiction. The results also supported both mediation hypotheses. FoMO significantly mediated the relationship between psychological distress and social media (β = 0.200, t = 7.706, p < 0.001). Similarly, boredom proneness significantly mediated the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction (β = 0.097, t = 3.696, p < 0.001). It should also be noted that the beta coefficients of both the mediational models were less compared to the direct one between psychological distress and social media addiction. This finding suggests a partial mediation effect.

Table 3.

Hypotheses testing

| Hypotheses | Path values | t values (bootstrapping at 5000) | p | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: There will be an increase in time spent on social media during COVID-19 pandemic | χ2 = 293.14 | – | < .001 | Accepted |

| H2: Psychological distress will predict social media addiction | .308 | 6.63 | < .001 | Accepted |

| H3: Psychological distress will predict FoMO | .457 | 11.798 | < .001 | Accepted |

| H4: FoMO will predict social media addiction | .438 | 10.680 | < .001 | Accepted |

| H5: Psychological distress will predict boredom proneness | .592 | 19.790 | < 0.001 | Accepted |

| H6: Boredom proneness will predict social media addiction | .164 | 3.770 | < .001 | Accepted |

| H7: FOMO will mediate the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction | .200 | 7.706 | < .001 | Accepted |

| H8: Boredom proneness will mediate the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction | .097 | 3.690 | < .001 | Accepted |

Discussion

The first aim of the present study was to compare the time spent on social media by adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerning social media usage before the pandemic, it was found that 17% of adolescents said they did not spend any time on social media, 39% said they spent less than half an hour daily on social media, 14% spent 2–3 h daily, and only 2% spent 4–5 h daily on social media. However, during the pandemic, participants said they engaged in more social media use compared to their pre-pandemic use. The findings indicated that 11% of the participants did not spend any time on social media, 20% used social media for less than half an hour daily, 27% used social media daily for 2–3 h, and 11% used social media daily for 4–5 h. These differences were found to be statistically significant.

This result of the present study is consistent with other studies. Karhu et al. (2021) reported that as opposed to the pre-pandemic era, the activity on social media has increased during the pandemic. Overall, the results supported H1. This can be attributed to the need to be socially connected and keep oneself updated with pandemic-related information, but this could be potentially detrimental for individuals who are at a higher risk for developing addiction (Dong et al., 2020). In the present study, 3.8% of respondents were classed as being at risk from social media addiction (i.e., scoring 24 or more out of 30 on the BSMAS) which is similar to other studies using the same cut-off score. More specifically, Luo et al. (2021) reported that 3.25% of their participants were addicted social media users, and Stănculescu (2022) reported that 4.25% of the participants were addicted social media users.

The second hypothesis of the present study dealt with psychological distress and social media addiction. The results showed that psychological distress significantly predicted social media addiction. This is consistent with the extant literature given that negative and distressing emotions are strongly associated with the risk of social media addiction (Huang et al., 2021). Moreover, depressed individuals may turn to social media-based interactions for validation by getting likes and followers (Hartanto et al., 2021). Ehrenreich and Underwood (2016) found that adolescent females who had internalizing symptoms such as anxiety and depression appear to use social media to relieve their negative mood states. There is also some supporting evidence in the COVID-19 context. For example, Panno et al. (2020) found a positive association between COVID-19-related distress and social media addiction, and COVID-19-related stress was found to be positively associated with addictive social media use (Zhao & Zhou, 2021). Therefore, the results of the present study provided support for the compensatory hypothesis (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014).

The next four hypotheses examined the impact of psychological distress on FoMO and boredom proneness, as well as the influence of FoMO and boredom proneness on social media addiction. As shown in Table 3, all four hypotheses (H3-H6) are supported. FoMO can be a natural consequence of anxiety and depression as both would lead to social isolation (Elhai et al., 2020b), and the results of the present study provided evidence for this line of reasoning. Moreover, FoMO is positively associated with social media addiction (Blackwell et al., 2017; Dempsey et al., 2019; Liu & Ma, 2020). There is evidence that boredom proneness is positively related to anxiety and depression (e.g., Elhai et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2022). In a recent study, Brosowsky et al. (2022) found that depression, anxiety, and stress were significantly and positively associated with boredom proneness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stockdale and Coyne (2020) found that for 3 years, bored individuals used social networking to alleviate their boredom with some becoming addicted to it. Whelan et al. (2020) found that boredom proneness was positively related to social media overload. Bozaci (2020) also reported that boredom proneness positively influences social media addiction. The results of the present study provided further support to the existing body of knowledge that all four constructs of psychological distress, FoMO, boredom proneness, and social media addiction were significantly and positively related to each other among Indian adolescents.

FoMO and boredom proneness were also examined as mediators in the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction. Table 3 clearly shows that FoMO and boredom proneness partially mediated the relationship between psychological distress and social media addiction, providing support for H7 and H8. Previous literature lends support to the findings but mostly in the context of problematic Internet use and smartphone addiction. FoMO has been found to mediate the relationships between depression and anxiety in problematic smartphone use severity (Elhai et al., 2018; Oberst et al., 2017; Wegmann et al., 2018). Elhai et al., (2020a,2020b) conducted a literature review concerning FoMO and concluded that “FoMO may be a mechanism that explains how some depressed/anxious people develop problematic internet use” (p.206).

Boredom proneness has been found to mediate the influence of anxiety and depression in problematic smartphone use (Elhai et al., 2018; Wegmann et al., 2018; Wolniewicz et al., 2020). To the best of our knowledge, Elhai et al. (2018) explored the role of boredom proneness as a mediator of depression and anxiety, and smartphone addiction, and found that boredom proneness mediated this relationship.

By highlighting the role of two mediators between psychological distress and social media addiction, the present research addresses the call by compensatory theorists (e.g., Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) to focus on the mediation and interaction effects. The results of the present study also supported the theoretical framework of the I-PACE model in the context of social media addiction because response variables in the I-PACE model (e.g., FoMO, boredom proneness) mediated the relationships between personal factors (psychological distress) and social media addiction.

It is well-accepted that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a variety of different mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, stress, loneliness, and psychological distress (e.g., Pappa et al., 2020; Chao et al., 2020). Additionally, the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is strongly associated with social media addiction (Panno et al., 2020; Zhao & Zhou, 2021). Closure of schools and consequent online teaching increased the screen time for adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in FoMO for many (Amran & Jamaluddin, 2022). There is also evidence that lockdown during the pandemic slowed down the perception of time, which resulted in boredom (Droit-Volet et al., 2020). Wessels et al. (2022) conducted a longitudinal study on the experience of boredom with the progression of the pandemic and found evidence that individuals experienced boredom during the initial phases of COVID-19 restrictions. The results of the present study provided the first empirical evidence that FoMO and boredom proneness were two possible pathways through which psychological distress resulted in social media addiction during COVID-19. Additionally, the study findings also highlight the need to introduce boredom intervention training (Parker et al., 2021) and FoMO reduction skills (both social and technical) (Alutaybi et al., 2020) among individuals who are experiencing psychological distress to avert the risk of developing problematic social media use.

Limitations

Despite the novel findings of the present study in an Indian context, the study has some specific limitations. The present study utilized a cross-sectional design conducted in India; therefore, the causal relationships between variables cannot be confirmed and generalizations to other countries and cultures cannot be made. Moreover, the data were collected online, and therefore, individuals without smartphones were not contacted which limits the generalization of the findings. Moreover, not all the items of FoMO and boredom proneness scales were used. A thorough psychometric evaluation of these modified scales would have provided more credence to the results. Another limitation was the reliance on a self-report method to collect data which is known to suffer from social desirability and other common method biases. The reliance on memory recall may have particularly been an issue in participants trying to recall the amount of time spent on social media before and during the pandemic.

Conclusion

Closure of schools in many parts of the world has been one of the most significant consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in online modes of teaching and learning in many countries, including India. Based on the self-report findings, the present study indicates there appears to have been a significant increase in social media usage among Indian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to their pre-COVID pandemic use. The results also showed that psychological distress, FoMO, and boredom proneness explained 56.5% of the variance in social media addiction. Moreover, FoMO and boredom proneness partially mediated the relationships between psychological distress with social media addiction. The present study also provided support for the utility of the compensatory model and the I-PACE model in the context of social media addiction. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first to provide evidence for the specific pathways examined here (FoMO and boredom proneness) in the relationships between mental health issues and social media addiction in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Availability of Data

Data is available on OFSHOME (OSF | Psychological distress and social media 505.sav).

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The research was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Faculty of Social Sciences, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was sought from the participants before going ahead with data collection.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abel T, McQueen D. The COVID-19 pandemic calls for spatial distancing and social closeness: Not for social distancing. International Journal of Public Health. 2020;65(3):231. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almahasees, Z., Mohsen, K., & Amin, M. O. (2021). Faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning during COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 6, 638470. 10.3389/feduc.2021.638470

- Alutaybi, A., Arden-Close, E., McAlaney, J., Stefanidis, A., Phalp, K., & Ali, R. (2019, October). How can social networks design trigger fear of missing out? 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 3758–3765). IEEE. 10.1109/SMC.2019.8914672

- Alutaybi A, Al-Thani D, McAlaney J, Ali R. Combating fear of missing out (FoMO) on social media: The FoMO-R method. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(17):6128. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amran MS, Jamaluddin KA. Adolescent screen time associated with risk factor of fear of missing out during pandemic Covid-19. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2022;25(6):398–403. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2021.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS. Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports. 2015;2(2):175–184. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS, Pallesen S. Social network site addiction - An overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;20(25):4053–4061. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a Facebook addiction scale. Psychological Reports. 2012;110(2):501–517. doi: 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Mo K, Peng Y, Hao W, Qu Y, Lei X, Yang Y. The relationship between the use of mobile social media and subjective well-being: The mediating effect of boredom proneness. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:3824. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best P, Manktelow R, Taylor B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: A systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;41:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez-Fernandez O, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Current Addiction Reports. 2015;2(2):156–162. doi: 10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biolcati R, Mancini G, Trombini E. Proneness to boredom and risk behaviors during adolescents’ free time. Psychological Reports. 2018;121(2):303–323. doi: 10.1177/0033294117724447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell D, Leaman C, Tramposch R, Osborne C, Liss M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;116:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozaci, I. (2020). The effect of boredom proneness on smartphone addiction and impulse purchasing: A field study with young consumers in Turkey. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics, and Business, 7(7), 509–517. 10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no7.509

- Brand M, Young KS, Laier C, Wölfling K, Potenza MN. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2016;71:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosowsky NP, Barr N, Mugon J, Scholer AA, Seli P, Danckert J. Creativity, boredom proneness and well-being in the pandemic. Behavioral Sciences. 2022;12(3):68. doi: 10.3390/bs12030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camargo, C. P., Tempski, P. Z., Busnardo, F. F., Martins, M. D. A., & Gemperli, R. (2020). Online learning and COVID-19: A meta-synthesis analysis. Clinics, 75, e2286. 10.6061/clinics/2020/e2286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Can L, Kaya N. Social networking sites addiction and the effect of attitude towards social network advertising. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2016;235:484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.11.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Gong M, Yu L, Dai B. Exploring the mechanism of social media addiction: An empirical study from WeChat users. Internet Research. 2020;30(4):1305–1328. doi: 10.1108/INTR-08-2019-0347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chao, M., Xue, D., Liu, T., Yang, H., & Hall, B. J. (2020). Media use and acute psychological outcomes during COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Anxiety Disorders,74, 102248. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen CY, Chen IH, Pakpour AH, Lin CY, Griffiths MD. Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during the COVID-19 school hiatus. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2021;24(10):654–663. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pablo GS, Serrano JV, Catalan A, Arango C, Moreno C, Ferre F, Fusar-Poli P. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;275:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, A. E., O'Brien, K. D., Tiamiyu, M. F., & Elhai, J. D. (2019). Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic Facebook use. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 9, 100150. 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dong H, Yang F, Lu X, Hao W. Internet addiction and related psychological factors among children and adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:751. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau A, Marchand A, Beaulieu-Prévost D. Epidemiology of psychological distress. Mental Illnesses-Understanding, Prediction and Control. 2012;69(2):105–106. doi: 10.5772/30872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet, S., Gil, S., Martinelli, N., Andant, N., Clinchamps, M., Parreira, L., & Dutheil, F. (2020). Time and Covid-19 stress in the lockdown situation: Time free, «dying» of boredom and sadness. PloS One, 15(8), e0236465. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Drouin M, McDaniel BT, Pater J, Toscos T. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2020;22:727–736. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood JD, Frischen A, Fenske MJ, Smilek D. The unengaged mind: Defining boredom in terms of attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7(5):482–495. doi: 10.1177/1745691612456044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich SE, Underwood MK. Adolescents’ internalizing symptoms as predictors of the content of their Facebook communication and responses received from peers. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2016;2(3):227–237. doi: 10.1037/tps0000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Rozgonjuk D, Liu T, Yang H. Fear of missing out predicts repeated measurements of greater negative affect using experience sampling methodology. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;262:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Vasquez JK, Lustgarten SD, Levine JC, Hall BJ. Proneness to boredom mediates relationships between problematic smartphone use with depression and anxiety severity. Social Science Computer Review. 2018;36(6):707–720. doi: 10.1177/0894439317741087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Yang H, Montag C. Fear of missing out (FOMO): Overview, theoretical underpinnings, and literature review on relations with severity of negative affectivity and problematic technology use. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;43:203–209. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Yu L, Luqman A. Understanding the formation mechanism of mobile social networking site addiction: Evidence from WeChat users. Behaviour and Information Technology. 2020;39:1176–1191. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2019.1653993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green-Hamann S, Campbell Eichhorn K, Sherblom JC. An exploration of why people participate in second life social support groups. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2011;16(4):465–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01543.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MD. Facebook addiction: Concerns, criticism, and recommendations: A response to Andreassen and colleagues. Psychological Reports. 2012;110:518–520. doi: 10.2466/01.07.18.PR0.110.2.518-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartanto A, Quek FY, Tng GY, Yong JC. Does social media use increase depressive symptoms? A reverse causation perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:335. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.641934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Zhang J, Duan W, He L. Peer relationship increasing the risk of social media addiction among Chinese adolescents who have negative emotions. Current Psychology, Advance Online Publication. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01997-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;31:351–354. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karhu, M., Suoheimo, M., & Häkkilä, J. (2021). People’s perspectives on social media use during COVID-19 pandemic. In: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia (pp. 123–130). ACM. 10.1145/3490632.3490666

- Kelly, H. (2020). Kids used to love screen time. Then schools made Zoom mandatory all day long. The Washington Post, September 4. Retrieved November 27, 2022, from: https://edpolicyinca.org/news/kids-used-love-screen-time-then-schools-made-zoom-mandatory-all-day-long

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Li C, Meng C, Guo X, Lv J, Fei J, Mei S. Psychological distress and internet addiction following the COVID-19 outbreak: Fear of missing out and boredom proneness as mediators. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2022;40:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Lin SL, Wu CP. The effects of parental monitoring and leisure boredom on adolescent’s internet addiction. Adolescence. 2009;44(176):993–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Ma J. Social support through online social networking sites and addiction among college students: The mediating roles of fear of missing out and problematic smartphone use. Current Psychology. 2020;39:1892–1899. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-0075-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T, Qin L, Cheng L, Wang S, Zhu Z, Xu J, Chen H, Liu Q, Hu M, Tong J, Hao W, Liao Y. Determination the cut-off point for the Bergen social media addiction (BSMAS): Diagnostic contribution of the six criteria of the components model of addiction for social media disorder. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2021;10(2):281–290. doi: 10.1556/2006.2021.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigam, C. (2020). Screen-time spike, learning issues: How e-class overdose is hurting kids. India Today, June 20. Retrieved November 27, 2022, from: https://www.indiatoday.in/mail-today/story/coronavirus-screen-time-learning-e-class-overdose-is-hurting-kids-1702322-2020-07-20

- Oberst U, Wegmann E, Stodt B, Brand M, Chamarro A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence. 2017;55:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panno A, Carbone GA, Massullo C, Farina B, Imperatori C. COVID-19 related distress is associated with alcohol problems, social media and food addiction symptoms: Insights from the Italian experience during the lockdown. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020;11:1314. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker PC, Tze VM, Daniels LM, Sukovieff A. Boredom intervention training Phase I: Increasing boredom knowledge through a psychoeducational video. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(21):11712. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski AK, Murayama K, DeHaan CR, Gladwell V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29:1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T, Chester A, Reece J, Xenos S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2014;3(3):133–148. doi: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Lewis RF. Frequent use of social networking sites is associated with poor psychological functioning among children and adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2015;18(7):380–385. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, H., Bush, K., Villeneuve, P. J., Hellemans, K. G., & Guimond, S. (2022). Social media addiction in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 9(4), e33450. 10.2196/33450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sheldon KM, Abad N, Hinsch C. A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(4):766–775. doi: 10.1037/a0022407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Dixit, A., & Joshi, G. (2020). Is compulsive social media use amid COVID-19 pandemic addictive behavior or coping mechanism? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 102290. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stănculescu, E. (2022). The Bergen social media addiction scale validity in a Romanian sample using item response theory and network analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s11469-021-00732-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stockdale LA, Coyne SM. Bored and online: Reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence. 2020;79:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struk AA, Carriere JS, Cheyne JA, Danckert J. A short boredom proneness scale: Development and psychometric properties. Assessment. 2017;24(3):346–359. doi: 10.1177/1073191115609996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teja, C.S. (2020). Parents dig deep into their pockets, online classes of children to blame. The Tribune, June 22. Retrieved November 27, 2022, from: https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/amritsar/parents-dig-deep-into-their-pockets-online-classes-of-children-to-blame-103089

- Van den Eijnden RJ, Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM. The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;61:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vannucci A, Flannery KM, Ohannessian CM. Social media use and anxiety in emerging adults. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;207:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal C, Lhaksampa T, Miller L, Platt R. Social media use and depression in adolescents: A scoping review. International Review of Psychiatry. 2020;32(3):235–253. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1720623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villanti, A. C., Johnson, A. L., Ilakkuvan, V., Jacobs, M. A., Graham, A. L., & Rath, J. M. (2017). Social media use and access to digital technology in US young adults in 2016. Journal of medical Internet research, 19(6), e196. 10.2196/jmir.7303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z., Yang, X., & Zhang, X. (2020). Relationships among boredom proneness, sensation seeking and smartphone addiction among Chinese college students: Mediating roles of pastime, flow experience and self-regulation. Technology in Society, 62, 101319. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101319

- Wang Y, Yang H, Montag C, Elhai JD. Boredom proneness and rumination mediate relationships between depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use severity. Current Psychology. 2022;41:5287–5297. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-01052-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wegmann, E., Ostendorf, S., & Brand, M. (2018). Is it beneficial to use Internet-communication for escaping from boredom? Boredom proneness interacts with cue-induced craving and avoidance expectancies in explaining symptoms of Internet-communication disorder. PloS One, 13(4), e0195742. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wegmann E, Oberst U, Stodt B, Brand M. Online-specific fear of missing out and internet-use expectancies contribute to symptoms of Internet-communication disorder. Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2017;5:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.abrep.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels M, Utegaliyev N, Bernhard C, Welsch R, Oberfeld D, Thönes S, von Castell C. Adapting to the pandemic: Longitudinal effects of social restrictions on time perception and boredom during the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05495-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan E, Islam AN, Brooks S. Is boredom proneness related to social media overload and fatigue? A stress–strain–outcome approach. Internet Research. 2020;30:869–877. doi: 10.1108/INTR-03-2019-0112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold BK. Using social media to our advantage: Alleviating anxiety during a pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2020;23(4):197–198. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.29180.bkw. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolniewicz CA, Rozgonjuk D, Elhai JD. Boredom proneness and fear of missing out mediate relations between depression and anxiety with problematic smartphone use. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies. 2020;2(1):61–70. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yakobi O, Danckert J. Boredom proneness is associated with noisy decision-making, not risk-taking. Experimental Brain Research. 2021;239(6):1807–1825. doi: 10.1007/s00221-021-06098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Cao X, Liu Z, Wang J. Excessive social media use at work: Exploring the effects of social media overload on job performance. Information Technology and People. 2018;31:1091–1112. doi: 10.1108/ITP-10-2016-0237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. L., Li, S., & Yu, G. L. (2019). The relationship between boredom tendency and cognitive failure of college students: The mediating effect of mobile phone addiction tendency and difference between the only child and non only child groups. Psychological Development and Education, 35, 344–351. 351. 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.03.1

- Zhao N, Zhou G. COVID-19 stress and addictive social media use (SMU): Mediating role of active use and social media flow. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:85. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Lee MKO. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites: Negative consequences on individuals. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;65:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on OFSHOME (OSF | Psychological distress and social media 505.sav).