Abstract

India is largely import dependent in meeting its domestic demand of edible oils. This study aims to discuss the consequences of recent global events such as COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war on edible oil imports. Due to prevailing supply chain disruptions and local shortages in significant supplier countries, international prices became highly volatile, and import volumes were hit severely. This led to an almost doubling of the cost of imports from US $ billion 9.52 in 2019–20 to US $18.70 billion in 2021–22, putting an enormous burden on the Indian exchequer. Overall, an increase in the price of all edible oils has been recorded since the later parts of 2021, exerting inflationary pressure on the food price index. As edible oils are part of staple diets, the import dependency of such a large magnitude makes India extremely vulnerable to external shocks. This calls for immediate attention to the issue of self-sufficiency (atma nirbharata) in edible oils production by emphasizing long-term measures.

Keywords: Edible oils, Import, Prices, COVID-19

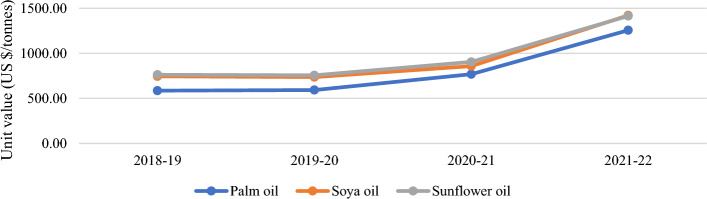

Edible oils are the most imported commodity after petroleum and gold, accounting for 40% of agricultural import bill and 3% of total import bill [1]. Around 60% of domestic consumption demand is met by imports. India’s import expenditure on edible oils went up to US $ 18.70 billion in 2021–22 from US $ 10.92 billion in 2020–21. The after-effects of the COVID-19-induced pandemic, export bans by major producing countries, and the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war have pushed up the edible oil import bill. India imported 13.39 million tonnes of edible oils worth US $11 billion during 2020–21 (Table 1). Although the overall quantity of imports declined by 8% (1.16 million tonnes) in 2020–21 compared to the previous year, import value rose by 15% due to higher prices. Similarly, in 2021–22, the import quantity has increased merely by 5.4% but import value has increased by 71% as compared to the previous year. For the same level of imports, the import bill nearly doubled from 2019–20 to 2021–2022, indicating costlier imports. The unit value of import of all edible oils has registered a sharp increasing trend after 2019–20 (Fig. 1). Since India is heavily import-dependent, the rising cost of imports due to prevailing external shocks is likely to put an enormous financial burden on the exchequer. Edible oils are an essential part of the Indian staple diet, hence quite instrumental in driving food price inflation. This reiterates the need for achieving self-sufficiency (atma nirbharata) in edible oils and reducing import dependency.

Table 1.

Import of edible oil (Quantity in Million tonnes and Value in US$ billion) Source: [1] Figures in parenthesis are percentage to the total

| Year | Palm oil | Soya oil | Sunflower oil | Rapeseed& Mustard oil | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Value | Quantity | Value | Quantity | Value | Quantity | Value | Quantity | Value | |

| 2018–19 | 8.94 (60.12) | 5.23 (53.92) | 3.19 (21.45) | 2.37 (24.43) | 2.58 (17.35) | 1.97 (20.31) | 0.16 (1.08) | 0.12 (1.24) | 14.87 (100.0) | 9.70 (100.0) |

| 2019–20 | 8.68 (59.66) | 5.14 (53.99) | 3.31 (22.75) | 2.44 (25.63) | 2.50 (17.18) | 1.89 (19.85) | 0.05 (0.34) | 0.05 (0.53) | 14.55 (100.0) | 9.52 (100.0) |

| 2020–21 | 7.52 (56.16) | 5.78 (52.93) | 3.64 (27.18) | 3.12 (28.57) | 2.18 (16.28) | 1.98 (18.13) | 0.04 (0.30) | 0.04 (0.37) | 13.39 (100.0) | 10.92 (100.0) |

| 2021–22 | 8.09 (57.34) | 10.17 (54.39) | 3.89 (27.57) | 5.53 (29.57) | 2.07 (14.67) | 2.92 (15.61) | 0.06 (0.43) | 0.07 (0.37) | 14.11 (100.0) | 18.70 (100.0) |

Fig. 1.

Unit value of import of edible oils

Out of the total edible oil imports, palm oil constituted a major share of 56%, followed by 27% of soya oil and 16% of sunflower oil during 2020–21. Indonesia and Malaysia are India’s major palm oil suppliers; soya oil is imported from Argentina and Brazil, and sunflower oil from Ukraine and Argentina.

The FAO food price index recorded an all-time high in March 2022, driven by a huge price surge in vegetable oils and cereals due to ongoing conflict [2]. The rise in price indices is mainly caused by the lower production of palm oil, soya oil, sunflower oil, and rapeseed and mustard oil in the supplier countries. The global palm oil quotations were high due to low production and labor shortages in Indonesia and Malaysia [2]. The Indonesian government had cut short the export quota to 70%, allowing the rest for sale in the local market. Indonesia has banned the export of palm oil from 28th April 2022 onwards to curb domestic shortage and ease domestic prices. International prices of soya oil also increased due to higher import demand from China, India, and the biodiesel sector. The drought in Argentina, which supplies around 70% of soya oil to India, further aggravated the supply situation in the international market. Ukraine was previously the sole supplier of more than 90% of sunflower oil to India, but the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war has forced India to shift its import base to Russia. India is also trying to source sunflower oil from Argentina.

COVID-19-induced lockdown and restrictions caused a decline in the domestic demand for oils during 2019–20, especially in the hotel, restaurant, and catering (HoReCa) segment. Subsequent lifting of the lockdown in the later part of the year 2021 and early 2022 led the domestic demand to pick up momentum slowly. According to Solvent Extractors Association, around a 68% jump in imports was observed in May 2021 compared to the same month last year. After the opening of the economy, wholesale prices of major edible oils witnessed a sharply rising trend (Fig. 2). All India year on year (YoY) variation in edible oil prices from January to May 2021 in ground nut oil was around 18–20%, 23–43% in mustard, 23–49% in soya oil, 30–56% in sunflower oil and 25–53% in palm oil. Overall, an increase in the prices of all edible oils has been recorded since the later parts of 2021.

Fig. 2.

Trend in wholesale price of major edible oils (all India average)

Although the price rise is expected to be favorable to the domestic producers, the actual accrual of benefit to the farmers is questionable. Minimum support prices (MSP) of edible oils have registered comparatively higher growth than rice and wheat since 2000, but their procurement remains very low. Only 3% of total oilseeds production is procured by the government, while staples like rice and wheat have relatively higher procurement levels. Procurement at MSP must be ensured to encourage larger acreage under oilseeds.

The government has already undertaken several initiatives to attain self-sufficiency in edible oils. The ad-hoc measures like import duty hikes or reductions were rigorously followed in the past three years to protect the interest of farmers, refineries, and consumers. The refined palm oil was kept under a restricted list in January 2020. However, in June 2021, the government lifted the ban and kept refined palm oil under the free list initially till 30th December 2021, which was later extended to 31st December 2022. The agri-cess on crude palm oil was reduced from 7.5 to 5% from 12th February 2022 to relieve consumers. The basic import duty on crude palm oil, crude soyabean oil, and crude sunflower oil was also removed. The basic duty on refined soyabean oil and refined sunflower oil has been slashed to 17.5% from 32.5% and in refined palm oil 12.5% from 17.5%. This move attempted to stabilize the prices and reduce the burden on consumers ahead of the festive seasons. These kinds of measures may provide short-term relief, but long-term measures are necessary to reduce import dependency [3].

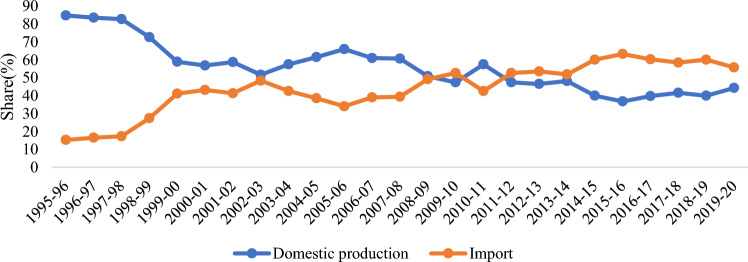

The current situation of worsening demand–supply mismatch was not observed prior to 2011–12 (Fig. 3). The yellow revolution, through Technology Mission on Oilseeds, coupled with price support, made India self-sufficient for a brief period during the 1990s. However, the withdrawal of price support under WTO agreements during later years led to the re-emergence of domestic shortage, and the situation continues [4]. Since 2012–13, the gap between domestic production and import has been widening.

Fig. 3.

Share of domestic production and import in total availability of edible oils in India

The yield gap in oilseeds between improved technology and farmers’ practices ranges from 21% in sesame to 149% in sunflower [5]. Widespread adoption of improved technologies at the farm level needs to be promoted to reduce the prevailing yield gap [6]. Research advances in biotechnology and gene editing could be utilized for yield improvement. Expansion of oilseed area by using fallow land and exploring non-traditional areas could be followed to increase production. The seed mini-kit program by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare allows the distribution of 8 lakh soybean seed kits and 74 thousand groundnut seed kits for the selected districts and 8.20 lakh of mini-kits of rapeseed &mustard for the selected states under National Food Security Mission-Oilseeds (NFSM-OS). The seed mini-kit program is likely to encourage the uptake of HYVs. Similarly, National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP) has been launched to promote countrywide crude palm oil production through area expansion [7]. NMEO-OP provides input assistance for planting material, intercropping, the establishment of seed gardens, nurseries, micro irrigation, etc. Promotion of supplementary sources of vegetable oils like rice bran oil, tree born oil could be alternative options to widen the edible oil consumption basket in the country. The Food Safety Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) has banned blending mustard oil with any other oil, opening up a new opportunity for mustard growers to increase production to meet the growing domestic demand for pure mustard oil. Only 30% of edible oil refineries capacity is currently utilized in the processing sector. Modernizing existing mills and investing in edible oil processing industries will improve processing capacity. The government policy to achieve self-sufficiency in edible oil should have a balanced approach to ensure better price realization for farmers without hurting consumers’ sentiments.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Agricultural Statistics at a Glance (2019) Directorate of economics and statistics ministry of agriculture and Farmers welfare, government of India. http://agricoop.nic.in/agristatistics.htm

- 2.FAO (2022)Monthly Price Update:Oilseeds,Oils & Meals. Markets and Trade Division https://www.fao.org/3/cb9566en/cb9566en.pdf

- 3.Renjini VR, Jha GK. Oilseeds sector in India: a trade policy perspective. Indian J Agric Sci. 2019;89(1):73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy DA. Policy implications of minimum support price for agriculture in India. Acad Lett. 2021 doi: 10.20935/AL2406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NFSM (2016) Present Status of Oilseed crops and vegetable oils in India. https://www.nfsm.gov.in/StatusPaper/NMOOP2018.pdf

- 6.Hegde DM. Carrying capacity of Indian agriculture. Curr Sci. 2012;102(6):867–873. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GOI (2016) Status paper on oil palm. Oilseeds division, department of agriculture, cooperation and Farmers welfare, ministry of agriculture and Farmers welfare