Abstract

The bifunctional enzyme phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphohydrolase/phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase (HisIE) catalyzes the second and third steps of histidine biosynthesis: pyrophosphohydrolysis of N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-ATP (PRATP) to N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-AMP (PRAMP) and pyrophosphate in the C-terminal HisE-like domain, and cyclohydrolysis of PRAMP to N-(5′-phospho-D-ribosylformimino)-5-amino-1-(5″-phospho-D-ribosyl)-4-imidazolecarboxamide (ProFAR) in the N-terminal HisI-like domain. Here we use UV–VIS spectroscopy and LC–MS to show Acinetobacter baumannii putative HisIE produces ProFAR from PRATP. Employing an assay to detect pyrophosphate and another to detect ProFAR, we established the pyrophosphohydrolase reaction rate is higher than the overall reaction rate. We produced a truncated version of the enzyme-containing only the C-terminal (HisE) domain. This truncated HisIE was catalytically active, which allowed the synthesis of PRAMP, the substrate for the cyclohydrolysis reaction. PRAMP was kinetically competent for HisIE-catalyzed ProFAR production, demonstrating PRAMP can bind the HisI-like domain from bulk water, and suggesting that the cyclohydrolase reaction is rate-limiting for the overall bifunctional enzyme. The overall kcat increased with increasing pH, while the solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effect decreased at more basic pH but was still large at pH 7.5. The lack of solvent viscosity effects on kcat and kcat/KM ruled out diffusional steps limiting the rates of substrate binding and product release. Rapid kinetics with excess PRATP demonstrated a lag time followed by a burst in ProFAR formation. These observations are consistent with a rate-limiting unimolecular step involving a proton transfer following adenine ring opening. We synthesized N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-ADP (PRADP), which could not be processed by HisIE. PRADP inhibited HisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from PRATP but not from PRAMP, suggesting that it binds to the phosphohydrolase active site while still permitting unobstructed access of PRAMP to the cyclohydrolase active site. The kinetics data are incompatible with a build-up of PRAMP in bulk solvent, indicating HisIE catalysis involves preferential channeling of PRAMP, albeit not via a protein tunnel.

Keywords: phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphohydrolase, phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase, Acinetobacter baumannii, enzyme kinetics, histidine biosynthesis, kinetic isotope effects, substrate channeling

Introduction

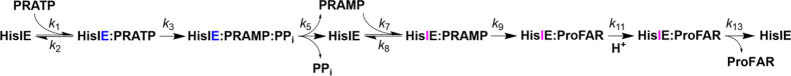

The first step of histidine biosynthesis comprises the reversible condensation of ATP and 5-phospho-α-D-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP) to generate N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-ATP (PRATP) and pyrophosphate (PPi), catalyzed by ATP phosphoribosyltransferase (ATPPRT).1 In some actinobacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), and in most archaea, the second and third steps of histidine biosynthesis are catalyzed by the enzymes phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphohydrolase (HisE) and phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase (HisI), respectively. However, in most bacteria, including Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii),2 the two reactions are catalyzed by the bifunctional enzyme phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphohydrolase/phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase (HisIE), comprised of an N-terminal domain homologous to HisI and a C-terminal domain homologous to HisE.3 HisIE catalyzes the Mg2+-dependent hydrolysis of PRATP to N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-AMP (PRAMP) and PPi, presumably in the C-terminal (HisE-like) domain, and the Zn2+-dependent ring-opening hydrolysis of PRAMP to N-(5′-phospho-D-ribosylformimino)-5-amino-1-(5″-phospho-D-ribosyl)-4-imidazolecarboxamide (ProFAR), presumably in the N-terminal (HisI-like) domain (Scheme 1).4

Scheme 1. HisIE-catalyzed Hydrolysis of PRATP Followed by Ring-Opening Hydrolysis of PRAMP.

Crystal structures of M. tuberculosis monofunctional HisE (PDB ID: 1Y6X)5 and Methanococcus thermoautotrophicum (M. thermoautotrophicum) monofunctional HisI (PDB ID: 1ZPS)6 have been reported, as were those of apoenzyme and AMP-bound bifunctional HisIE from Shigella flexneri (PDB ID: 6J22 and 6J2L)7 and HisN2 (the nomenclature adopted in plants) Medicago truncatula (PDB ID: 7BGM and 7BGN).8 Mechanistic investigations of HisI have been described,9,10 but no detailed functional characterization has been reported for HisE or HisIE.

Enzymes involved in the histidine biosynthesis pathway are attractive targets for antibiotic development, as they carry out essential functions during infection and have no homologues in humans. For instance, histidine biosynthesis protects M. tuberculosis from host-imposed starvation.11 In A. baumannii, high-throughput transposon library analysis demonstrated that six enzymes of the histidine biosynthetic pathway, including HisIE, are required for the bacterium’s persistence in the lungs during pneumonia.2 In an independent study, knockout of the gene encoding another enzyme in the pathway, imidazole glycerol phosphate synthase, significantly increased host survival in a murine model of pneumonia caused by A. baumannii.12 Histidine is required for zinc acquisition and lung infection by A. baumannii,13 and it is a precursor in the biosynthesis of acinetobactin, a siderophore essential for A. baumannii virulence.14 Extracellular histidine concentration is lower than 2 μM in the lungs of mice, regardless of A. baumannii infection,13 while the histidine inhibition constant for A. baumannii ATPPRT, the enzyme allosterically inhibited by the amino acid in a negative feedback control mechanism, lies between 83 and 282 μM.15 As this value is expected to reflect the metabolite concentration the cell needs to function,16 this may explain the reliance of this bacterium on histidine biosynthesis to establish and sustain pneumonia.15

The need for novel antibiotics effective against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii was classified as a critical priority by the World Health Organisation.17 Moreover, ventilator-associated pneumonia is one of the most common manifestations of A. baumannii infection, and it is linked to high mortality rates.18 The identification and characterization of promising novel molecular targets are key steps to enable rational drug design.19 Thus, the characterization of A. baumannii HisIE (AbHisIE) catalysis may lay the foundation for inhibitor design against this enzyme on the path toward novel antibiotics against A. baumannii.

Here, the gene encoding the putative AbHisIE was cloned and expressed, and the recombinant protein was purified. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS), differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF), steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics, biocatalytic syntheses of PRAMP and N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-ADP (PRADP), solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effects, and viscosity effects were used to characterize the enzyme and its catalyzed reaction. Furthermore, the HisE-like domain of AbHisIE (heretofore referred to as AbHisEdomain) was cloned and shown to catalyze the reaction normally catalyzed by monofunctional HisE, paving the way to study the pyrophosphohydrolysis reaction independently.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All commercially available chemicals were used without further purification. BaseMuncher endonuclease was purchased from Abcam. Ampicillin, dithiothreitol (DTT), and isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were purchased from Formedium. Escherichia coli (E. coli) DH5α (high efficiency) and BL21(DE3) cells, Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit, and Dpn1 were purchased from New England Biolabs. QIAprep Spin Miniprep, PCR clean-up, and Plasmid Midi kits were purchased from Qiagen. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free Complete protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Roche. Ammonium bicarbonate, ammonium sulfate, ATP, deuterium oxide (D2O), glycerol, histidine, imidazole, lysozyme, PRPP, potassium chloride, d-ribose 5-phosphate, tricine, phosphoenolpyruvate, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) pyruvate kinase (ScPK), S. cerevisiae myokinase (ScMK), NiCl2, and ZnCl2 were purchased from Merck. Agarose, dNTPSs, kanamycin, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) EnzCheck Pyrophosphate Kit, MgCl2, NaCl, PageRuler Plus Prestained protein ladder, and Phusion High-Fidelity polymerase were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific. Psychrobacter arcticus HisGS (PaHisGS), M. tuberculosis pyrophosphatase (MtPPase), and tobacco etch virus protease (TEVP) were produced as previously described,20 as was E. coli PRPP synthetase (EcPRPPS).21

Expression of AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain

The DNA encoding AbHisIE (A. baumannii strain ATCC17978) and AbHisEdomain, codon optimized for expression in E. coli, were purchased as gBlocks (IDT). The AbHisEdomain gBlock also encoded a TEVP-cleavable N-terminal His-tag. Each gBlock was PCR-modified and inserted into a modified pJexpress414 plasmid using Gibson Assembly22 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each construct was transformed into DH5α competent cells, sequenced (DNA Sequencing & Services, University of Dundee) to confirm the insertion of the genes and that no mutations had been introduced. Constructs were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, which were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) containing 100 μg mL–1 ampicillin at 37 °C until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6–0.8, at which point cells harboring the AbHisIE expression construct were equilibrated to 20 °C, while cells harboring the AbHisEdomain expression construct remained at 37 °C before expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG. Cells were grown for an additional 20 h, harvested by centrifugation (6774 g, 15 min, 4 °C) and stored at −20 °C. The genes encoding AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain were cloned and expressed independently of one another.

Purification of AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain

All purification procedures were performed on ice or at 4 °C using an ÄTKA Start FPLC system (GE Healthcare). All SDS-PAGE used a NuPAGE Bis-Tris 4–12% Precast Gel (ThermoFisher Scientific). For AbHisIE purification, cells were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5) supplemented with 0.2 mg mL–1 lysozyme, 750 U BaseMuncher endonuclease, and half a tablet of EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were lysed in a cell disruptor (Constant systems) at 30 kpsi, and centrifuged at 48,000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. AbHisIE was precipitated by dropwise addition of 1.5 M ammonium sulfate in buffer A to the supernatant followed by stirring for 1 h. The sample was centrifuged at 48,000 g for 30 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in buffer A, dialyzed against 3 × 2 L of buffer A, filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane and loaded onto a 10 mL HiTrap Q FF column pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 10 column volumes(CV) of 2.5% buffer B (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 2 M NaCl) and the adsorbed proteins were eluted with a 30 CV linear gradient of 2.5–15% buffer B. Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and those containing AbHisIE were pooled and dialyzed against 2 × 2 L of buffer C (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl), filtered through a 0.45 μM membrane and loaded onto a ZnCl2-charged 5 mL HisTrap FF column pre-equilibrated with buffer C. The column was washed with 10 CV of buffer C and the adsorbed proteins were eluted with a 20 CV linear gradient of 0–15% buffer D (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and those containing AbHisIE were pooled, concentrated using a 10,000-MWCO ultrafiltration membrane, and loaded onto a HiPrep 26/60 Sephacryl S200 HR column equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 1 CV of buffer A. Fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and those containing AbHisIE were pooled, concentrated using a 10,000-MWCO ultrafiltration membrane, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of AbHisIE was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop) using a theoretical extinction coefficient (ε280) of 40,910 M–1 cm–1 (ProtParam tool – Expasy). The identity of the protein was confirmed via tryptic digest and LC–MS/MS analysis of the tryptic peptides performed by the University of St Andrews BSRC Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry facility.

For AbHisEdomain purification, cells were resuspended in buffer A (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) supplemented with 0.2 mg mL–1 lysozyme, 750 U BaseMuncher endonuclease, and half a tablet of EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Cells were lysed in a cell disruptor (Constant systems) at 30 kpsi and centrifuged at 48,000 g for 30 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane and loaded onto a NiCl2-charged 5 mL HisTrap FF column pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 10 CV of buffer A, and adsorbed proteins were eluted with a 20 CV gradient of 0–100% buffer B (50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and those containing AbHisEdomain were pooled, mixed with TEVP (1 mg of TEVP to 15 mg of AbHisEdomain) and dialyzed against 2 × 2 L of buffer C (20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol (v/v), 2 mM DTT) and against 1 × 2 L of buffer A. Samples were filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane and loaded onto a 5 mL HisTrap FF pre-equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 10 CV of buffer A, and the eluate was collected, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, concentrated using a 10,000-MWCO ultrafiltration membrane, dialyzed against 2 × 2 L of buffer D (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0), aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of AbHisEdomain was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop) using an ε280 of 12,950 M–1 cm–1 (ProtParam tool – Expasy). The exact mass of the protein was determined via electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis by the University of St Andrews BSRC Proteomics and Mass Spectrometry facility.

Syntheses of PRATP, PRAMP, and PRADP

For PRATP synthesis, a 10 mL reaction contained 8 μM EcPRPPS, 15 μM PaHisGS, 25 μM MtPPase, 0.5 mM d-ribose-5-phosphate, and 0.75 mM ATP, 72 U mL–1ScPK, 72 U mL–1ScMK, 100 mM tricine pH 8.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT. For PRAMP synthesis, a 10 mL reaction contained 15 μM AbHisEdomain in addition to the aforementioned components. For PRADP synthesis, a 10 mL reaction contained 30 μM PaHisGS, 25 μM MtPPase, 12 mM ADP, 10 mM PRPP, 100 mM tricine pH 8.5, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT. Reactions were incubated for 90 min at room temperature. Proteins were removed by passage through a 10,000-MWCO Vivaspin centrifugal concentrator and each filtrate was loaded onto a 20 mL HiTrap Q HP column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with water in a Bio-Rad NGC FPLC. The column was washed with 3 CV of water and 5 CV of either 6% or 18% solution B (1 M ammonium bicarbonate) for either PRAMP or PRATP purification, respectively, and with 1 CV of water and 5 CV of 10% solution B for PRADP. PRAMP was eluted with a 20-CV linear gradient of 6–24% solution B. PRATP was eluted with a 20-CV linear gradient of 18–30% solution B. PRADP was eluted with a 25-CV linear gradient of 10–30% solution B. Fractions exhibiting absorbance at 290 nm were pooled, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C. The concentration of each compound was determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop) at 290 nm in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 (ε290 = 2800 M–1 cm–1).23

PRADP and PRATP were solubilized in water and loaded onto an Atlantis Premier BEH C18 AX column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) on a Waters ACQUITY UPLC system coupled to a Xevo G2-XS QToF mass spectrometer equipped with an ESI source. The UPLC mobile phase was (A) 10 mM ammonium acetate pH 6, (B) acetonitrile, and(C) 10 mM ammonium acetate pH 10. The following sequence was applied: 0–0.5 min at 90% (A) and 10% (B); 0.5–2.5 min step change from 90% (A) and 10% (B) to 50% (A), 10% (B) and 40% (C); 2.5–7 min re-equilibration to 90% (A) and 10% (B), the flow rate of 0.3 mL min–1. ESI data were acquired in negative mode with a capillary voltage of 2500 V. The source and desolvation gas temperatures of the mass spectrometer were 100 and 250 °C, respectively. The cone gas flow was 50 L h–1, whilst the gas flow was 600 L h–1. A scan was performed between 50 and 1200 m/z. A lockspray signal was measured and a mass correction was applied by collecting every 10 s, averaging 3 scans of 0.5 s each, using Leucine Enkephalin as a correction factor for mass accuracy.

PRAMP was solubilized in water and loaded onto a Premier BEH C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm) held at 40 °C on a Waters Arc HPLC system coupled to a QDa mass detector equipped with an ESI source. PRAMP was eluted with an isocratic mobile phase of 0.1% formic acid, 1% acetonitrile in water at a flow rate of 0.4 mL min–1. MS scans were performed followed by the selection of the desired ion for PRAMP. ESI data were acquired in negative mode with a capillary voltage of 800 V both as a mass range (50–1250) scan (cone voltage of 30 V) and single-ion (558) recording (cone voltage ramp of 30–100 V). The source and probe temperatures of the mass spectrometer were 120 and 600 °C, respectively.

Detection of ProFAR by LC–MS

Reactions (500 μL) were prepared in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 16 μM AbHisIE, and 135 μM PRATP. Control reactions lacked AbHisIE. The reactions were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and passed through 10,000 MWCO Vivaspin centrifugal concentrators. ProFAR was detected exactly as described above for PRADP and PRATP detection by LC–MS.

DSF-Based Thermal Denaturation of AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain

DSF measurements (λex = 490 nm, λem = 610 nm) were performed in 96-well plates on a Stratagene Mx3005p instrument. Reactions (50 μL) contained either 8.3 μM AbHisIE (in the presence or absence of 50 μM PRATP) or 8.7 μM AbHisEdomain in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 15 mM MgCl2. Invitrogen Sypro Orange (5×) was added to all wells. Controls lacked protein and were subtracted from the corresponding protein-containing samples. Thermal denaturation curves were recorded over a temperature range of 25–93 °C with increments of 1 °C min–1. Three independent measurements were carried out.

AbHisIE Direct and Continuous Assay Detecting ProFAR

Typically, initial rates were measured at 25 °C in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT, unless otherwise stated. Reactions (500 μL) were monitored for an increase in absorbance at 300 nm corresponding to the formation of ProFAR (Δε300 = 6700 M–1 cm–1 at pH 7.5)9 for 60 s in 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes (Hellma) in a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer outfitted with a CPS unit for temperature control. Control reactions lacked AbHisIE. The effect of added Zn2+ on activity was determined by measuring initial rates in the presence or absence of added 50 μM ZnCl2 and 13.5 μM PRATP, 12 mM MgCl2, and 20 nM AbHisIE. The effect of added Mg2+ on activity was determined by measuring the initial rates in the presence of 0–24 mM MgCl2, 37 μM PRATP, and 20 nM AbHisIE. The enzyme concentration dependence of the initial rate was determined in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 12 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT in the presence of 0–42 nM AbHisIE and 37 μM PRATP. Progress curves of ProFAR formation from 40 μM PRATP were obtained in the presence of 21 nM AbHisIE by monitoring the reaction for 1000 s.

AbHisIE Saturation Kinetics with PRATP and PRAMP

Initial rates of ProFAR formation were measured in the presence of 18 nM AbHisIE, 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, and varying concentrations of either PRATP (0–42 μM) or PRAMP (0–80 μM). Two independent measurements were carried out.

AbHisIE Saturation Kinetics in the Presence of Glycerol

Initial rates of ProFAR formation were measured in the presence of 18 nM AbHisIE 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, and varying concentrations of PRATP (0–42 μM) in the presence of 0–27% glycerol (v/v). Two independent measurements were carried out.

Determination of PRATP ε300nm at Different pH Values

The ε300 of PRATP at pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0 were determined by measuring the absorbance (NanoDrop) at 300 nm of known concentrations of PRATP in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.0: 0.45, 0.91, and 1.8 mM; pH 7.5: 0.51, 1.0, and 2 mM; pH 8.0: 0.46, 0.92, and 1.8 mM). These known concentrations were determined independently via absorbance at 290 nm of a high-concentration stock solution of PRATP in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5. This stock solution was in turn diluted into 100 mM HEPES at different pH values. The pH of the final PRATP solutions was measured to ensure that they stayed at pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0. Controls were measured by following the same dilution procedure in the absence of PRATP, and their absorbance at 300 nm was subtracted from each value with PRATP. The final values were then subtracted from the ε300 of ProFAR (8000 M–1 cm–1).9 to generate Δε300. Three independent measurements were carried out for each concentration at each pH.

AbHisIE Rates at pL 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0

The initial rates of ProFAR formation were measured in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, and varying PRATP concentrations (2.3–37 μM for pH 7.0; 2.6–42 μM for pH 7.5; 1.4–40 μM for pH 8.0). AbHisIE concentrations were 31, 18, and 7.5 nM for pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0, respectively. To ensure enzyme stability in the pH range, AbHisIE was diluted in buffer at either pH 7.0 or 8.0 prior to activity assay at pH 7.5. The solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effects were determined by measuring the initial rates of ProFAR formation in 100 mM HEPES pD 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0 (pD = pH + 0.4),24 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, varying PRATP concentrations (2.3–59 μM for pD 7.0; 2.4–38 μM for pD 7.5; 2.6–48 μM for pD 8.0), and AbHisIE concentrations of 186, 74, and 19 nM for pD 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0, respectively, in 99.5% D2O (v/v). The initial rates of ProFAR formation from varying concentrations of PRAMP (5–80 μM) were measured in 100 mM HEPES pL 7.5, and 8.0, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, and 18 nM AbHisIE in either H2O or 99.5% D2O (v/v). Two independent measurements were carried out for each concentration at each pL.

AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain Coupled Assay Detecting PPi

The pyrophosphohydrolase activities of the AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain were independently assessed via the EnzCheck Pyrophosphate Assay kit.25 The initial rates were measured in the presence of 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM DTT, 200 μM 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine ribonucleoside (MESG), 1 U mL–1 of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), and 0.03 U mL–1 of PPase. The reactions (500 μL) were monitored for the increase in absorbance at 360 nm (Δε360nm = 11,000 M–1 cm–1) upon phosphorolysis of MESG to 2-amino-6-mercapto-7-methylpurine at 25 °C for 60 s in 1 cm path length cuvettes (Hellma) using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer outfitted with a CPS unit for temperature control. The initial rates of PPi formation were measured in the presence of 8.4 μM PRATP and either 0–6.4 nM AbHisIE or 0–20 nM AbHisEdomain. AbHisIE substrate saturation curves were collected with varying concentrations of PRATP (0–16 μM) and 3.2 nM AbHisIE. Controls lacked, in turn, AbHisIE or AbHisEdomain, PRATP, and PPase. Two independent measurements were carried out.

Pre-Steady-State Kinetics

The approach to steady-state for ProFAR formation by AbHisIE under multiple-turnover conditions at 25 °C was carried out by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 300 nm for 0.2 s in an Applied Photophysics SX-20 stopped-flow spectrophotometer outfitted with a 5 μL mixing cell (0.5 cm path length and 0.9 ms dead time) and a circulating water bath. Each syringe contained 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT. In addition, in the first experiment, one syringe contained 10 μM AbHisIE and the other, 50 μM PRATP. In the second experiment, one syringe contained 20 μM AbHisIE and the other, 100 μM PRATP. The reaction was triggered by rapidly mixing 55 μL from each syringe. In each experiment, 4 traces were collected with 3000 data points per trace. Controls lacked enzyme.

AbHisIE Inhibition by PRADP

The initial rates of ProFAR formation from PRATP were measured at 25 °C in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 15 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM DTT in the presence of 18 nM AbHisIE and varying concentrations of PRADP (0–160 μM). Alternatively, the initial rates of ProFAR formation from 20 μM PRAMP were measured in the presence of 18 nM AbHisIE and either 0 or 268 μM PRADP. Incubation of 42 μM PRADP with either 0 or 18 nM AbHisIE under ProFAR formation assay conditions for 30 min revealed no increase in absorbance at 300 nm. The incubation of 40 μM PRADP with either 0 or 18 nM AbHisIE under PPi formation coupled assay conditions for 5 min detected no increase in absorbance at 360 nm. For comparison, under corresponding assay conditions, ProFAR is detected in less than 10 s from 37 μM PRATP and 10 nM AbHisIE, and PPi, in less than 10 s from 8.4 μM PRATP and 1.6 nM AbHisIE.

Analysis of Kinetics Data

Kinetics data were analyzed by the non-linear regression function of SigmaPlot 14.0 (SPSS Inc.). Data points and error bars represent mean ± SEM, and kinetic and equilibrium constants are given as mean ± fitting error. Substrate saturation curves were fitted to eq 1, solvent viscosity effects were fitted to eq 2, solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effects were fitted to eq 3, and inhibition data were fitted to eq 4. In eqs 1–4, v is the initial rate, kcat is the steady-state turnover number, KM is the Michaelis constant, ET is total enzyme concentration, S is the concentration of substrate, k0 and kη are the rate constants in the absence and presence of glycerol, respectively, ηrel is the relative viscosity of the solution, m is the slope, Fi is the fraction of deuterium label, Ekcat/KM and Ekcat are the solvent isotope effect minus 1 on kcat/KM (D2O(kcat/KM)), and kcat (D2Okcat) respectively, vi and v0 are the initial rates in the presence and absence of inhibitor, respectively, IC50 is the half-maximal inhibitory concentration, and h is the Hill coefficient. D2O(kcat/KM) and D2Okcat at pL 7.0 and 7.5 were also calculated as the ratios of the relevant rate constants in H2O and D2O.

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

Results and Discussion

Purification, Biophysical, and Biochemical Characterization of AbHisIE and AbHisEdomain

These results, including Figures S1–S14, are described and discussed in Supporting Information.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for AbHisIE with PRATP

To uncover which of the two reactions, i.e., either pyrophosphohydrolase-catalyzed or cyclohydrolase-catalyzed, is rate-limiting, the steady-state kinetic parameters were determined based on the detection of ProFAR and PPi. The AbHisIE overall reaction displayed Michaelis–Menten kinetics when PRATP concentration was varied and either ProFAR or PPi formation was measured (Figure 1). When ProFAR formation was measured, fitting the data to eq 1 yielded an apparent steady-state catalytic constant (kcatProFAR) and apparent Michaelis constant (KM) shown in Figure 1, resulting in kcatProFAR/KM of (1.4 ± 0.3) × 106 M–1 s–1. The values obtained here are comparable to those reported for ProFAR formation by Methanococcus vannielii HisI (kcat = 4.1 s–1; kcat/KM = 4.1 × 105 M–1 s–1) and M. thermoautotrophicum HisI (kcat = 8 s–1; kcat/KM = 6 × 105 M–1 s–1), but in the case of these monofunctional HisI, the substrate was PRAMP.6,9 When PPi formation was monitored, data fitting to eq 1 yielded apparent kcatPPi and apparent KM as depicted in Figure 1, leading to kcatPPi/KM of (3.1 ± 0.4) × 106 M–1 s–1.

Figure 1.

Substrate saturation curves and associated apparent steady-state kinetic parameters for AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation and PPi formation. Lines are best fit to eq 1. A Student’s t-test indicated kcatProFAR and kcatPPi are statistically different (p < 0.025).

Assuming catalytically independent active sites in the HisE- and HisI-like domains of AbHisIE, and PRAMP binding to the HisI-like domain in a bimolecular step, a minimum kinetic sequence depicting flux through the bifunctional enzyme reaction from PRATP can be summarized in Scheme 2, with the release of PRAMP and PPi from the HisE-like domain combined in one step (k5) since the order (if any) of product release is not known. Besides the irreversibility of the two hydrolytic steps (k3 and k9), product release steps (k5 and k11) are presumed irreversible under initial-rate conditions in the absence of added products.26

Scheme 2. The Minimum Kinetic Sequence for the AbHisIE-catalyzed Reaction.

The makeup of the steady-state kinetic parameters shown in Figure 1 will differ depending on which product is being measured, even though only PRATP concentration is varied. When PPi is detected, kcatPPi, at saturating levels of PRATP, and kcatPPi/KM, at PRATP levels approaching zero, are defined by simple expressions as in eqs 5 and 6, respectively. On the other hand, when ProFAR is detected, the corresponding steady-state parameters are more complex. Increasing concentrations of PRATP must eventually lead to saturation of the HisI-like domain active site with PRAMP, as seen from the saturation kinetics obtained when the final product is monitored (Figure 1), and kcatProFAR is given by eq 7. As PRATP levels approach zero, so do PRAMP levels, and kcatProFAR/KM is defined by eq 8 (eqs 5–8 derived according to Cleland’s Net Rate Constant method,26 see Supporting Information for details).

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

Given the complexity of the AbHisIE catalytic sequence and the statistically different yet comparable magnitudes of kcatPPi and kcatProFAR, it is possible that both reactions are kinetically relevant to kcatProFAR, with the cyclohydrolase reaction making a larger contribution.

Steady-State Kinetic Parameters for AbHisIE with PRAMP

To determine if PRAMP can bind the HisI-like domain from bulk solvent and to test its kinetic competence as a substrate for the cyclohydrolase-catalyzed reaction, steady-state kinetic parameters for ProFAR formation were determined with PRAMP as the varying substrate, bypassing the necessity for the pyrophosphohydrolase-catalyzed reaction altogether. ProFAR formation was readily detected (Figure 2A), and the reaction followed Michaels–Menten kinetics, with data fitting to eq 1 yielding steady-state kinetic parameters displayed in Figure 2B. The similar kcatProFAR values when either PRATP or PRAMP was the substrate suggest PRAMP can bind the HisI-like domain of AbHisIE from bulk solvent and the cyclohydrolase-catalyzed reaction limits the overall rate of the bifunctional catalytic cycle. The kcatProFAR/KM for PRAMP of (4.4 ± 0.4) × 105 M–1 s–1 is 3-fold lower than the kcatProFAR/KM for PRATP, which speaks against diffusion in and out of bulk solvent as the main path for PRAMP transfer from the first active site to the second, favoring the hypothesis that AbHisIE catalysis involves proximity channeling.27,28

Figure 2.

Kinetic competence of PRAMP. (A) Time courses of ProFAR formation from different PRAMP concentrations. Thick lines are mean traces from two independent measurements; thin black lines are linear regressions of the data. (B) PRAMP saturation curve and associated apparent steady-state kinetic parameters for AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation. The line is best fit to eq 1.

Solvent Viscosity Effects on AbHisIE-Catalyzed ProFAR Formation

In order to evaluate whether or not diffusional steps involving either substate binding or product release limit the rate of AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from PRATP, solvent viscosity effects were determined by measuring reaction rates at different concentrations of the microviscogen glycerol (Figure 3A and Table S1). Plots of kcatProFAR/KM ratios versus relative viscosity (Figure 3B) and kcatProFAR ratios versus relative viscosity (Figure 3C) produced slopes of 0 and −0.01, respectively. These data indicate neither PRATP and PRAMP binding to nor PRAMP, PPi, and ProFAR release from AbHisIE is rate-limiting in the reaction.29 This contrasts with the first enzyme of histidine biosynthesis, ATPPRT, where significant solvent viscosity effects on kcat revealed diffusion of the product from the enzyme to be rate-limiting.30

Figure 3.

Solvent viscosity effects on AbHisIE-catalyzed reaction. (A) Substrate saturation curves for AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation in the presence and absence of glycerol. Lines are best fit to eq 1. (B) Solvent viscosity effects on kcatProFAR/KM. (C) Solvent viscosity effects on kcatProFAR. Lines are best fit to eq 2.

Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects on AbHisIE-Catalyzed ProFAR Formation

Solvent deuterium isotope effects, defined as the ratio of rate constants (kinetic isotope effects) or equilibrium constants (equilibrium isotope effects) for reactions taking place in H2O and D2O, can inform on rate-limiting proton-transfer steps in enzymatic reactions.31 To uncover potential rate-liming proton-transfer steps in the AbHisIE reaction, a solvent deuterium isotope effect study was undertaken. Because the presence of D2O can increase the pKa of kinetically relevant ionizable groups by ∼0.5, solvent isotope effects would ideally be measured in a pH-independent region of a pH-rate profile.32 In the case of AbHisIE, this is further complicated by the fact that, while ProFAR absorbance is pH independent above pH 5,33 PRATP and PRAMP absorbance at 300 nm is pH-dependent (PRATP and PRAMP have identical absorbance spectra in this region),23 which would shift the Δε300 from its value at pH 7.5.9 Hence, Δε300 was determined for the conversion of PRATP to ProFAR under initial-rate conditions by measuring ε300 for PRATP at pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0 (Figure S14) and subtracting each value from the ε300 for ProFAR9 (Table S2). Importantly, the Δε300 for ProFAR at pH 7.5 obtained by this method (6690 M–1 cm–1) is within 0.15% of the published value, lending confidence to the approach. With PRATP as the substrate, both kcatProFAR/KM and kcatProFAR increased as the pL increased from 7.0 to 8.0, although kcatProFAR/KM seemed to peak at pH 7.5 when the reaction took place in H2O (Figure 4), indicating that deprotonation of one or more groups increases the reaction rate.

Figure 4.

AbHisIE kinetics in H2O and D2O. (A) PRATP saturation curves at pH 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0. Lines are best fit to eq 1. (B) PRATP saturation curves at pD 7.0, 7.5, and 8.0. Lines are best fit to eq 3. (C) Dependence of kcatProFAR/KM on pL. (D) Dependence of kcatProFAR on pL. (E) PRAMP saturation curves at pL 7. Lines are best fit to eq 1 for data in H2O and to eq 3 for data in D2O. L denotes either H or D.

Solvent deuterium isotope effect measurement at a plateau region of the pH-rate profile could not be accomplished here. Therefore, caution must be wielded to interpret the magnitudes of the isotope effects reported in Table 1, especially for D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) where the propagated experimental uncertainties were sizable owing to the uncertainties in the second-order rate constants obtained in D2O (Figure 4C). As a trend, D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) and D2OkcatProFAR decreased as the pL increased, suggesting proton-transfer steps accompany steps contributing less to the observed reaction rate as the pH increases. It should be noted that kcatProFAR/KM and kcatProFAR varied by a maximum of 4- and 3.4-fold, respectively, across the pH range. This is particularly relevant for D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) and D2OkcatProFAR at pL 7.5, which are higher than what could be accounted for by pL changes alone.

Table 1. Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects and pH Effects on Steady-State Parameters for AbHisIE-Catalyzed ProFAR Formation.

| parameter | pL 7.0 | pL 7.5 | pL 8.0 |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcatProFAR (s–1) | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.4 |

| KM (μM) | 8 ± 1 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 10 ± 2 |

| kcatProFAR/KM (M–1 s–1) | (3.5 ± 0.5) × 105 | (1.4 ± 0.3) × 106 | (9.6 ± 0.9) × 105 |

| D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) | 12 ± 4a | 12 ± 5a | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| D2OkcatProFAR | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

Values calculated as the ratios of the relevant kinetic parameters in H2O and D2O.

The reactions taking place in the pyrophosphohydrolase and cyclohydrolase active sites are proposed to involve nucleophilic attack by Mg2+- and Zn2+-activated water molecules, respectively,5,7,10 and it is reasonable to assume water coordination by the metal will be in equilibrium in the free AbHisIE. As Mg2+-activated34,35 and Zn2+-activated32 H2O/D2O can have inverse fractionation factors (ϕM-OL ∼ 0.7–0.9), the observed D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) will be equal to the product of an inverse equilibrium solvent isotope effect (D2OKeq < 1) and any subsequent solvent kinetic isotope effects. This means the normal kinetic isotope effect portion of D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) has a larger value than what was observed, for instance, at pH 7.0 and 7.5, likely the result of more than one proton in flight during a rate-limiting step for kcatProFAR/KM. At pH 8.0, D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) becomes modestly inverse, probably reflecting an inverse D2OKeq on metal-water coordination once a slow proton-transfer step at lower pH becomes fast at this higher pH. The proposed catalytic mechanism for cyclodrolysis of PRAMP10 is reminiscent of that proposed for the Zn2+-dependent metalloenzyme AMP deaminase, where an inverse D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) of ∼0.7 was also reported, followed by a proton inventory implicating at least two proton transfers in a rapid equilibrium step involving Zn2+-water coordination.36 While D2OkcatProFAR decreases at pH 8.0, it remains normal and significant, indicating protonation steps reporting on kcatProFAR/KM and kcatProFAR are separated by an irreversible step. Importantly, at all pHs tested, at least one proton is in flight during the rate-limiting step for kcatProFAR, which our results indicate has larger contribution from the cyclohydrolysis reaction.

At pH 7.5, when PRAMP was employed as a substrate to bypass the pyrophospholysis reaction, the D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) was only 1.4 ± 0.1 (Figure 4E). This suggests a large portion of the D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) observed with PRATP as a substrate reports on PRATP pyrophosphohydrolysis. Assuming, hypothetically, the Zn2+-bound water molecule responsible for the cyclohydrolysis of PRAMP would induce a D2OKeq of ∼0.7 (based on common fractionation factors attributed to Zn2+-bound water),32 the kinetic isotope effect portion of the D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) with PRAMP as a substrate would have a magnitude of ∼2.32 This also suggests a D2O(kcatProFAR/KM) of ∼8.5 originating in the PRATP pyrophosphohydrolysis reaction, probably involving more than one proton in flight. D2OkcatProFAR was 2.1 ± 0.1 (Figure 4E) with PRAMP as a substrate. This suggests at least one proton is in flight during the rate-limiting step for kcatProFAR from the AbHisIE:PRAMP complex, and this contributes about half the overall D2OkcatProFAR from the AbHisIE:PRATP complex.

Lag and Burst Phases of ProFAR Formation from PRATP

To uncover additional information on rate-limiting steps of AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR synthesis from PRATP, the approach to steady state was monitored upon rapid mixing of AbHisIE and PRATP at pH 7.5 (Figure 5). The curves could not be fitted to an equation because, even though PRATP concentration was in 5-fold excess to enzyme concentration, PRAMP concentration was not, as it was being formed in situ. Qualitatively, the data are interpreted as follows. As PRATP concentrations used were at least 10-fold the KM obtained when PPi formation was assayed, the lag phase, which is shorter at the higher enzyme concentration, reflects mostly the PRAMP formation rate from the nearly saturated HisE active site of AbHisIE, with no appreciable formation of ProFAR. As ProFAR production progresses, eventually the HisI-like active site is nearly saturated by PRAMP, leading to ProFAR formation resembling a burst that precedes the steady-state reaction. Supporting this interpretation, linear regressions of the linear phases yielded apparent steady-state rate constants of 4.2 ± 0.1 and 4.16 ± 0.08 s–1, in reasonable agreement with kcatProFAR. Furthermore, the y-axis intercepts of the linear regressions indicating the concentrations of on-enzyme ProFAR formed in the burst phase, 4.8 ± 0.2 and 8.2 ± 0.3 μM, approach the corresponding AbHisIE concentrations. However, the kcatPPi of 8.3 s–1 would allow only ∼0.75 turnovers in ∼0.09 s, the apparent time required to saturate the HisI active site with PRAMP (Figure 5). Even if all AbHisIE is bound to PRATP, only ∼3.75 and ∼7.5 μM of free PRAMP would be produced from 5 and 10 μM AbHisIE, respectively, in 0.09 s, concentrations which are below the PRAMP KM of 11 μM. This suggests the preferred pathway for the transfer of PRAMP from the pyrophosphohydrolase domain to the cyclohydolase domain avoids significant diffusion into bulk solvent. Too short a lag time in consecutive reactions to allow the intermediate to accumulate enough into bulk solvent before rebinding to the next active site has been invoked as characteristic of substrate channeling.27 A pre-steady-state burst was also observed in ATPPRT catalysis,30,37 and product release was shown to be rate-limiting based on solvent viscosity effects on kcat.30

Figure 5.

Rapid kinetics of approach to a steady state of AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR production from PRATP. The dashed lines are linear regressions of the linear phases.

PRADP Inhibits AbHisIE-Catalyzed Pyrophosphorolysis

ADP can replace ATP as a substrate of ATPPRT, which generates PRADP.30AbHisIE, however, failed to produce ProFAR, PPi, or Pi when PRADP replaced PRATP as a substrate. As PRADP is a close structural analogue of both PRAMP and PRATP, we tested whether it might act as an AbHisIE inhibitor. PRADP inhibited AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from PRATP in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6A), and data fitting to eq 4 yieded an IC50 of 52 ± 4 μM. However, even 268 μM PRADP could not inhibit AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from 20 μM PRAMP (Figure 6B). This suggests that PRADP binds to the HisE-like domain of AbHisIE and inhibits pyrophosphohydrolysis of PRATP to PRAMP. The β-phosphate group of PRADP might prevent its binding to the HisI-like domain of AbHisIE, allowing ProFAR to form unincumbered from PRAMP directly. This provides further evidence of how independently the two active sites are able to operate and demonstrates the probable channeling of PRAMP does not involve a tunnel through the protein connecting the two active sites.28 A protein tunnel shielded from bulk solvent was also disfavoured as a connection between the two domains based on crystal structures of HisIE orthologues,7,8 and cannot be readily envisioned from our AlphaFold-based structural model (Figure S4A).

Figure 6.

AbHisIE inhibition by PRADP. (A) Dose-dependence curve of AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from PRATP in the presence of PRADP. The line is the best fit to eq 4. (B) Initial rates of AbHisIE-catalyzed ProFAR formation from PRAMP in the presence and absence of PRADP. Thin black lines are linear regressions of the traces which produced initial rates of 0.0565 ± 0.0004 and 0.0534 ± 0.0004 μM s–1 in the absence and presence of PRADP.

Implications for AbHisIE Catalysis

The presence of a burst preceding the steady state indicates a step following adenine ring-opening limits kcatProFAR. While this is commonly interpreted as product release being rate-limiting,30,38 the lack of solvent viscosity effects on kcatProFAR rules out slow diffusion of ProFAR from AbHisIE.29 Moreover, the sizable D2OkcatProFAR means at least one proton transfer is associated with this step.31,32 In addition, it is clear from steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic analyses that kcatPPi is not large enough to allow PRAMP to accumulate into the bulk solvent at the levels required to saturate the cyclohydrolase active site, and some form of proximity channeling28 must be the preferred means of PRAMP transfer. Based on the inhibition of the pyrophosphohydrolase activity but not the cyclohydrolase activity by PRADP, channeling does not involve tunneling through the protein, and probably still involves bimolecular binding of PRAMP to the cyclohydrolase active site being faster than diffusion into bulk solvent. Hence, the catalytic cycle depicted in Scheme 2 must be expanded to include preferential partition of newly synthesized PRAMP toward binding the HisI-like active site as opposed to diffusion into bulk water, and at least a slow unimolecular step (k11) involving a proton transfer following adenine ring opening but preceding ProFAR release (Scheme 3). This might be, for instance, a proton-transfer-linked conformational change that triggers ProFAR dissociation.

Scheme 3. Expanded Kinetic Sequence for the AbHisIE-Catalyzed Reaction.

In this revised catalytic sequence, kcatProFAR for ProFAR synthesis from PRATP is given by eq 9 (see Supporting Information for details). It should be pointed out that the rate constants in Schemes 2 and 3 do necessarily represent microscopic rate constants governing elementary steps, but potentially macroscopic rate constants38 defining the minimum catalytic path from PRATP to ProFAR.

| 9 |

Metabolic advantages associated with channeling, such as increased flux through a biosynthetic pathway and protection of intermediates from the action of enzymes external to the pathway,28 may have favored the evolution of bifunctionality in AbHisIE. It should be pointed out, however, that simple fusion of enzymes is neither sufficient nor required to ensure substrate channeling, as exemplified by the lack of channeling in the multifunctional AROM complex39 and the presence of channeling in the monofunctional proteins constituting the purinosome.40 Another potential advantage of gene fusion includes a fixed ratio of gene products for a set of consecutive reactions.41 Any fitness advantage associated with a bifunctional HisIE must be organism-specific, since other bacteria, such as M. tuberculosis have separate genes encoding monofunctional HisE and HisI.3,5 Future kinetic characterization of the AbHisEdomain will elucidate how much, if any, of the catalytic ability of this domain is compromised by the loss of the HisI-like domain.

The inability of AbHisIE to utilize PRADP as a substrate for either of its reactions is somewhat surprising with regards to its pyrophosphohydrolase activity. Other members of the α-helical NTP pyrophosphohydrolase superfamily, to which the HisE-like domain of AbHisIE belongs, such as protozoan dUTPases, can efficiently hydrolyze both dUTP, releasing PPi, and dUDP, releasing Pi, to dUMP.42 Unlike what its three-dimensional fold would predict, the pyrophosphohydrolase specificity of AbHisIE seems reminiscent of trimeric all-β dUTPases, which cannot hydrolyze dUDP.43 In trimeric dUTPases, dUDP acts as a competitive inhibitor, sitting in the active site in the same orientation non-hydrolysable dUTP analogues do, and crystal structures of these enzymes in complex with dUDP shed light on how catalysis proceeds.44,45 Given their structural similarities, PRADP presumably acts as a competitive inhibitor against PRATP, and it could prove useful for obtaining a crystal structure of AbHisIE, or other HisE enzymes, with a substrate analogue bound in the active site to furnish insight into the catalytic mechanism.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (Grant BB/M010996/1) via EASTBIO Doctoral Training Partnership studentships to G.F. and B.J.R., and by the University of St Andrews via a StARIS summer research bursary to S.K.L. The authors thank Dr. Andrew S. Murkin for insightful discussions. The authors are grateful to Reviewer 1 for insightful suggestions regarding substrate channeling.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PRPP

5-phospho-α-D-ribosyl-1-pyrophosphate

- PRATP

N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-ATP

- ATPPRT

ATP phosphoribosyltransferase

- HisE

phosphoribosyl-ATP pyrophosphohydrolase

- PPi

pyrophosphate

- HisI

phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase

- phosphoribosyl-ATP

pyrophosphohydrolase/phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase

- PRAMP

N1-(5-phospho-β-D-ribosyl)-AMP

- ProFAR

N-(5′-phospho-D-ribosylformimino)-5-amino-1-(5″-phospho-D-ribosyl)-4-imidazolecarboxamide

- AbATPPRT

A. baumannii ATPPRT

- AbHisIE

A. baumannii HisIE

- LC–MS

liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- DSF

differential scanning fluorimetry

- AbHisEdomain

truncated AbHisIE containing only the HisE-like domain

- kcat

steady-state catalytic constant

- KM

Michaelis constant

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.3c01111.

Additional results and discussion on the characterization of AbHisIE (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ames B. N.; Martin R. G.; Garry B. J. The First Step Of Histidine Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1961, 236, 2019–2026. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N.; Ozer E. A.; Mandel M. J.; Hauser A. R. Genome-Wide Identification Of Acinetobacter Baumannii Genes Necessary For Persistence In The Lung. mBio 2014, 5, e01163–e01114. 10.1128/mBio.01163-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alifano P.; Fani R.; Lió P.; Lazcano A.; Bazzicalupo M.; Carlomagno M. S.; Bruni C. B. Histidine Biosynthetic Pathway And Genes: Structure, Regulation, And Evolution. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 60, 44–69. 10.1128/mr.60.1.44-69.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. G.; Berberich M. A.; Ames B. N.; Davis W. W.; Goldberger R. F.; Yourno J. D. Enzymes And Intermediates Of Histidine Biosynthesis In Salmonella Typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 1971, 17, 3–44. 10.1016/0076-6879(71)17003-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Javid-Majd F.; Yang D.; Ioerger T. R.; Sacchettini J. C. The 1.25 Å Resolution Structure Of Phosphoribosyl-ATP Pyrophosphohydrolase From Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 627–635. 10.1107/S0907444908007105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaraman J.; Myers R. S.; Boju L.; Sulea T.; Cygler M.; Jo Davisson V.; Schrag J. D. Crystal Structure Of Methanobacterium Thermoautotrophicum Phosphoribosyl-AMP Cyclohydrolase HisI. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 10071–10080. 10.1021/bi050472w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhang F.; Nie Y.; Shang G.; Zhang H. Structural Analysis Of Shigella Flexneri Bi-Functional Enzyme HisIE In Histidine Biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 540–545. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witek W.; Sliwiak J.; Ruszkowski M. Structural And Mechanistic Insights Into The Bifunctional HISN2 Enzyme Catalyzing The Second And Third Steps Of Histidine Biosynthesis In Plants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9647. 10.1038/s41598-021-88920-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ordine R. L.; Klem T. J.; Davisson V. J. N1-(5’-Phosphoribosyl)Adenosine-5’-Monophosphate Cyclohydrolase: Purification And Characterization Of A Unique Metalloenzyme. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 1537–1546. 10.1021/bi982475x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ordine R. L.; Linger R. S.; Thai C. J.; Davisson V. J. Catalytic Zinc Site And Mechanism Of The Metalloenzyme PR-AMP Cyclohydrolase. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 5791–5803. 10.1021/bi300391m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedy A.; Ashraf A.; Jha B.; Kumar D.; Agarwal N.; Biswal B. K. De Novo Histidine Biosynthesis Protects Mycobacterium Tuberculosis From Host IFN-Γ Mediated Histidine Starvation. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 410. 10.1038/s42003-021-01926-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Guitián M.; Vázquez-Ucha J. C.; Álvarez-Fraga L.; Conde-Pérez K.; Lasarte-Monterrubio C.; Vallejo J. A.; Bou G.; Poza M.; Beceiro A. Involvement Of HisF In The Persistence Of Acinetobacter Baumannii During A Pneumonia Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 310. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan Z. R.; Palmer L. D.; Skaar E. P. Histidine Utilization Is a Critical Determinant of Acinetobacter Pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00118–e00120. 10.1128/IAI.00118-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Pérez K.; Vázquez-Ucha J. C.; Álvarez-Fraga L.; Ageitos L.; Rumbo-Feal S.; Martínez-Guitián M.; Trigo-Tasende N.; Rodríguez J.; Bou G.; Jiménez C.; et al. In-Depth Analysis of the Role of the Acinetobactin Cluster in the Virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 752070 10.3389/fmicb.2021.752070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read B. J.; Fisher G.; Wissett O. L. R.; Machado T. F. G.; Nicholson J.; Mitchell J. B. O.; da Silva R. G. Allosteric Inhibition of Acinetobacter baumannii ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase by Protein:Dipeptide and Protein:Protein Interactions. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 197–209. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c00539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J. C.; Pardee A. B. The Enzymology Of Control By Feedback Inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 1962, 237, 891–896. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E.; Carrara E.; Savoldi A.; Harbarth S.; Mendelson M.; Monnet D. L.; Pulcini C.; Kahlmeter G.; Kluytmans J.; Carmeli Y.; et al. Discovery, Research, And Development Of New Antibiotics: The WHO Priority List Of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria And Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub Moubareck C.; Hammoudi Halat D. Insights into Acinetobacter baumannii: A Review of Microbiological, Virulence, and Resistance Traits in a Threatening Nosocomial Pathogen. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 119. 10.3390/antibiotics9030119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdgate G. A.; Meek T. D.; Grimley R. L. Mechanistic Enzymology In Drug Discovery: A Fresh Perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 115–132. 10.1038/nrd.2017.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroek R.; Ge Y.; Talbot P. D.; Glok M. K.; Bernas K. E.; Thomson C. M.; Gould E. R.; Alphey M. S.; Liu H.; Florence G. J.; et al. Kinetics and Structure of a Cold-Adapted Hetero-Octameric ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 793–803. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alphey M. S.; Fisher G.; Ge Y.; Gould E. R.; Machado T. G.; Liu H.; Florence G. J.; Naismith J. H.; da Silva R. G. Catalytic And Anticatalytic Snapshots Of A Short-Form ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5601–5610. 10.1021/acscatal.8b00867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G. Synthesis Of DNA Fragments In Yeast By One-Step Assembly Of Overlapping Oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 6984–6990. 10.1093/nar/gkp687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. W.; Ames B. N. Phosphoribosyladenosine Monophosphate, An Intermediate In Histidine Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1965, 240, 3056–3063. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)97286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomaa P.; Schaleger L. L.; Long F. A. Solvent Deuterium Isotope Effects on Acid-Base Equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964, 86, 1–7. 10.1021/ja01055a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webb M. R. A Continuous Spectrophotometric Assay For Inorganic Phosphate And For Measuring Phosphate Release Kinetics In Biological Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992, 89, 4884–4887. 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W. W. Partition Analysis And The Concept Of Net Rate Constants As Tools In Enzyme Kinetics. Biochemistry 1975, 14, 3220–3224. 10.1021/bi00685a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. S. Fundamental Mechanisms Of Substrate Channeling. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 308, 111–145. 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)08008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareek V.; Sha Z.; He J.; Wingreen N. S.; Benkovic S. J. Metabolic channeling: predictions, deductions, and evidence. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 3775–3785. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadda G.; Sobrado P. Kinetic Solvent Viscosity Effects as Probes for Studying the Mechanisms of Enzyme Action. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 3445–3453. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher G.; Thomson C. M.; Stroek R.; Czekster C. M.; Hirschi J. S.; da Silva R. G. Allosteric Activation Shifts the Rate-Limiting Step in a Short-Form ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 4357–4367. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schowen K. B.; Schowen R. L. Solvent Isotope Effects Of Enzyme Systems. Methods Enzymol. 1982, 87, 551–606. 10.1016/S0076-6879(82)87031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez P. L.; Murkin A. S. Inverse Solvent Isotope Effects in Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions. Molecules 2020, 25, 1933. 10.3390/molecules25081933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. W.; Ames B. N. Intermediates In The Early Steps Of Histidine Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1964, 239, 1848–1855. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)91271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konsowitz L. M.; Cooperman B. S. Solvent Isotope Effect In Inorganic Pyrophosphatase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis Of Inorganic Pyrophosphate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976, 98, 1993–1995. 10.1021/ja00423a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten W. E.; Lai C.-J.; Cook P. F. Inverse Solvent Isotope Effects In The NAD-Malic Enzyme Reaction Are The Result Of The Viscosity Difference Between D2O And H2O: Implications For Solvent Isotope Effect Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5914–5918. 10.1021/ja00127a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merkler D. J.; Schramm V. L. Catalytic Mechanism Of Yeast Adenosine 5’-Monophosphate Deaminase. Zinc Content, Substrate Specificity, pH Studies, And Solvent Isotope Effects. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 5792–5799. 10.1021/bi00073a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedreno S.; Pisco J. P.; Larrouy-Maumus G.; Kelly G.; de Carvalho L. P. Mechanism Of Feedback Allosteric Inhibition Of ATP Phosphoribosyltransferase. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 8027–8038. 10.1021/bi300808b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. A.1 Transient-State Kinetic Analysis of Enzyme Reaction Pathways. In The Enzymes, Sigman D. S., Ed.; Academic Press, 1992; Vol. 20 pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Arora Verasztó H.; Logotheti M.; Albrecht R.; Leitner A.; Zhu H.; Hartmann M. D. Architecture And Functional Dynamics Of The Pentafunctional AROM Complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 973–978. 10.1038/s41589-020-0587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareek V.; Tian H.; Winograd N.; Benkovic S. J. Metabolomics And Mass Spectrometry Imaging Reveal Channeled De Novo Purine Synthesis In Cells. Science 2020, 368, 283–290. 10.1126/science.aaz6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fani R.; Brilli M.; Fondi M.; Lió P. The Role Of Gene Fusions In The Evolution Of Metabolic Pathways: The Histidine Biosynthesis Case. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, S4. 10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Zarco F.; Camacho A. G.; Bernier-Villamor V.; Nord J.; Ruiz-Pérez L. M.; González-Pacanowska D. Kinetic Properties And Inhibition Of The Dimeric dUTPase- dUDPase From Leishmania major. Protein Sci. 2001, 10, 1426–1433. 10.1110/ps.48801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroz O. V.; Murzin A. G.; Makarova K. S.; Koonin E. V.; Wilson K. S.; Galperin M. Y. Dimeric dUTPases, HisE, And MazG Belong To A New Superfamily Of All-Alpha NTP Pyrophosphohydrolases With Potential ″House-Cleaning″ Functions. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 347, 243–255. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Nafría J.; Harkiolaki M.; Persson R.; Fogg M. J.; Wilson K. S. The Structure Of Bacillus subtilis Spβ Prophage dUTPase And Its Complexes With Two Nucleotides. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011, 67, 167–175. 10.1107/S0907444911003234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauter Z.; Persson R.; Rosengren A. M.; Nyman P. O.; Wilson K. S.; Cedergren-Zeppezauer E. S. Crystal Structure Of dUTPase From Equine Infectious Anaemia Virus; Active Site Metal Binding In A Substrate Analogue Complex. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 285, 655–673. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.