Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Anger is a natural feeling which is essential for survival, however, which can impair functioning if it is excessive. Adolescents need to be equipped with skills to cope with their anger for the promotion of their health and safety. This study aims to examine the effectiveness of anger management program on anger level, problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment among school-going adolescents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

An experimental, pre-test–post-test control group design with a multistage random sampling was adopted to select 128 school-going adolescents aged between 13 and 16 years. Experimental group received six sessions of anger management program, while control group received one session on anger management skill after the completion of post-assessment for both the groups. Sessions included education on anger, ABC analysis of behavior and relaxation training, modifying anger inducing thoughts, problem solving, and communication skills training. Assessment done after the 2 months of anger management program. Data were analyzed through descriptive and inferential statistics.

RESULTS:

Study reveals the improvement in the problem solving skills (81.66 ± 4.81), communication skills (82.40 ± 3.82), adjustment (28.35 ± 3.76), and decreased anger level (56.48 ± 4.97). Within the experimental and between the experimental and control group, post-test mean scores differed significantly (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION:

The results revealed that the anger management program was effective in decreasing anger level and increasing problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment among school-going adolescents.

Keywords: Adjustment, adolescent, anger management, communication, problem solving

Introduction

Anger is a natural feeling which is essential for survival, however, which can impair functioning if it is excessive. Various factors contribute to maladaptive anger in adolescents; among peer influence is an important factor.[1] Displaying aggressive behavior may be a way to gain popularity or high social status by demonstrating power or control. It may be a response to the perceived threat of isolation or loss of social standing among the peers.[2,3,4,5] The devastating impact of unhealthy anger makes it imperative to address anger issues in adolescents.

Some of the factors found to be associated with anger are lack of problem solving and communication skills and skills to adapt with changing situations. Adjusting to the changing environment is found to be one of the common problems in adolescents.[6] Lack of problem solving skills makes adolescents vulnerable to anger when they face unfairness or criticism. Developing proper communication skills serves as a base for children to be in congruence with their environment, establishes healthy social relationships, and regulates their reactions emotionally.[7] There is a positive relationship between problem solving approach and communication skills.[8] Anger acts as an emotional barrier to communication which hampers the information processing in the brain and leads to inadequate logical discussion hampering the productive contribution to solving problems.[9]

When children have the awareness and skills to manage the negative emotions such as anger and aggression, they can choose an appropriate course of action, thereby avoiding inappropriate and destructive behavior.[10] Adolescents need to be equipped with skills to cope with their anger in a productively for the promotion of their health and safety.[11]

Several behavioral intervention programs have been developed to help adolescents cope with anger. The main aim of the anger management intervention is to develop an awareness and meaning of anger, its physical and psychological effects, and its expression.[12,13,14]

A meta-analysis conducted on anger management interventions indicated that emotional awareness, relaxation techniques, problem solving cognitive-behavioral approaches, and coping skill training are effective in reducing negative emotional and behavioral outcomes including anger and aggressive behavior.[15] Commonly used therapeutic techniques for managing anger include affective education, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring, problem solving skills, social skills training, and conflict resolution. These techniques are individually tailored and are found to improve adolescents’ psychological and physical well-being, reduce anger, aggression and protect the mental health of the society.[16,17,18,19,20]

A systematic review suggests that combinations of cognitive behavioral therapy and problem solving skills, communication skills, self-instruction, and role play were very effective in reducing anger or aggression. Group-based anger management interventions conducted in classroom or school settings are a more effective method for school-going adolescents rather than individual sessions.[21]

International Society of Psychiatric-Mental Health Nurses recommends that mental health nurses can bring change in the school environment by providing effective anger management skills for adolescents to prevent violent and aggressive behaviors. A school health nurse can also play a role in anger management among adolescents by conducting psycho-education programs at home, school, and in the community. This will enhance the social and coping skills to manage anger effectively and prevent future problems.[22,23,24]

Increasing anger-related issues are seen in schools and colleges across the world. Anger serves as a precursor for aggression, violence, and behavioral and conduct disorders.[25,26] Uncontrolled anger may cause extreme violence in the future.[27] In this context, there was a need for anger management training to improve the effective coping, problem solving, and communication skills of adolescents in the classroom in relation to anger management. A plethora of studies has provided the empirical ground in the selection of interventions that were used in the present study. There is little published research concerning the relative efficacy of anger management on problem solving skill, communication skill, and adjustment among adolescents’ group interventions. The current study addresses this dearth of research by evaluating outcomes of anger management program. It includes essential skills which are appropriate for the adolescent group. This anger management program helps adolescents to manage their anger in a healthy way and promotes healthy peer relationships and school environment.

Purpose

The purpose of the research is to find out the effectiveness of anger management program on anger level, problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment among school-going adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

The study was conducted in randomly selected schools with an experimental, pre-test–post-test control group design.

Study participants and sampling

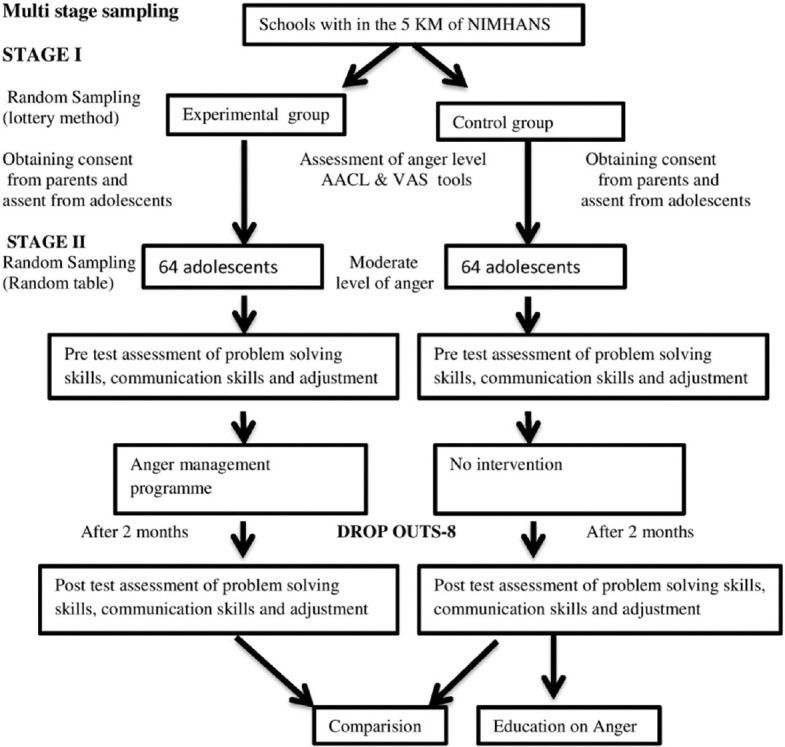

A total of 128 school-going adolescents aged between 13 and 16 years were selected by multistage random sampling technique. [Figure 1 illustrates the multistage sampling process in the study].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of data collection

Data collection tool and technique

Sociodemographic profile

The following characteristics were assessed: age, gender, education and type of school, parents’ education and occupation, and type of family.

Anger assessment checklist (AACL)

Anger assessment checklist (AACL) was developed by Karpe (1993). The items were divided into the following parameters of anger:

a) Intensity, b) Frequency, c) Mode of expression, d) Duration, and e) Effect upon interpersonal relations (IPRs). Each statement was to be rated on a five-point scale (scores 1–5) from “never” to “always” based on the extent to which the statement was applicable to them. The scores of the tool ranged between 35 and 175 classified into: 35 to 46.5 clinically not significant, 46.6 to 93.2 mild level of anger, 93.3 to 139.7 moderate level of anger, and 139.8 to 175 severe anger. Internal consistency of the AACL was 0.89.

Visual analog scale (VAS)

The visual analog scale (VAS) is a ten-centimeter-long line marked from 0 to 10, at an interval of one centimeter each. Zero indicated no anger, and 10 indicated the maximum amount of anger experienced. Adolescents were explained about the VAS and asked to rate their level of anger on VAS. This is divided into: 0 indicates no anger, 1–3 mild anger, 4–6 moderate anger, and 7–10 severe anger.

Solving problems checklist

It is developed by Barkman and Machtmes (2002).[28] It measures the communication skills of adolescents aged 12–18 years. This 24-item scale assesses youth's problem solving ability by examining the frequency of use of the following skills that are needed to engage in problem solving: 1. Identify/Define the Problem, 2. Analyze Possible Causes or Assumptions, 3. Identify Possible Solutions, 4. Select Best Solution, 5. Implement the Solution, and 6. Evaluate Progress and Revise as Needed. Higher scores indicate greater problem solving skills. Internal consistency was 0.86.

Communication scale

It is developed by Barkman and Machtmes (2002).[28] It measures the communication skills of adolescents aged 12–18 years. The scale has 23 items measuring the frequency of the use of certain skills which are needed for effective communication practices: ability to recognize ones’ own style of communication, ability to recognize and value other styles of communication, practicing empathy, altering ones’ communication style to combat with others styles of communication (communicative adaptability), conveying the essential and intended information, and interaction management. Higher scores indicate greater communication skills. Internal consistency was 0.79.

Pre-adolescent adjustment scale (PAAS)

It is developed by Rao, Ramalingaswamy, and Sharma (1976). It measures the adjustment of adolescents toward the areas of home, school, peers, and teachers and in general matters. The PAAS although the scale was developed for pre-adolescents, it can also be used with adolescents. PAAS consists of 40 items and are divided into five subareas, viz. Home-9, School-8, Teachers-8, Peers-8, and General-7. High positive scores indicate high adjustment in that area, while high negative scores indicate high maladjustment in that area. Test–retest reliability coefficient ranged from 0.22 to 0.60 for different areas, and the test was validated against teacher's rating.

Ethical consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from institute ethical committee [No.NIMH/DO/IEC (BEH.Sc.DIV0/2016)]. The students were briefed about the study, and informed consent forms were sent to the parents through them. Consent was obtained from parents and assent from students for participation in the study.

Procedure

All the students from the selected schools who gave assent and could get parental consent were assessed for anger level, problem solving skill, communication skill, and adjustment using anger assessment checklist (AACL), problem solving checklist, communication scale, and PAAS. AACL, problem solving check list, communication scale, and PAAS were translated to Kannada language and back-translated to English by an independent person and then matched with the original questionnaire to ensure validity of the translation.

Anger management program

Anger management program was developed by referring the systematic reviews and meta-analysis studies.[29,30] Anger management program and tools used to collect the data were validated by faculty of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences Bangalore, Karnataka, India.

Data collection

Permission was obtained from Deputy Director of Public Instruction (DDPI) and South Zone Block Education Officer (BEO). For the feasibility of the study and accessibility of the adolescents, schools were selected with in the 5 km radius of the institute. A list of 10 schools was received from BEO office. The school principals of all the 10 school were approached for permission. Two school principals declined to give permission. Thus, eight schools were included. School principals gave permission to conduct study in eighth and ninth grade. These schools included government schools (run by the government fund), private-aided schools (schools run by trust with the help of government), and private-unaided schools (managed by a person without government aid). Eight schools were randomly allocated to the experimental and control group by lottery method. A basic information sheet about the study was sent to parents, and assent for screening anger level was taken from adolescents. Anger assessment checklist was administered to the students with prior scheduling without disturbing the academic activity. Students who could read and answer the questionnaires in English or Kannada were included in the study, and those who have conduct disorder and/or ADHD as per the teachers report were excluded. The adolescents were assessed for anger level by using AACL and VAS. Total 1300 students were screened for anger level, from which 220 were incomplete questionnaires, 70 students did not bring consent from their parents, and 7 were absent. Mild level of anger was presented in 320 adolescents, moderate level of anger was present in 663 adolescents, and 20 adolescents had severe level of anger. Handouts of anger management program were given to the adolescents with mild and severe levels of anger. Adolescents with severe level of anger were referred for psychological help. Adolescents with moderate level of anger (663) were randomly selected for the study (64 students in each group) by using a random number table. The students were briefed about the study, and informed consent forms were sent to the parents through them. Consent was taken from parents and assent from students for participation in the study.

Pre-test assessment was conducted for both experimental and control group adolescents (with moderate level of anger) using solving problems, communication, and adjustment tools.

The adolescents of schools allocated to experimental group were made into groups of 6–8 adolescents, and pretest tools were administered. Six sessions of anger management program were conducted for each adolescent group by using demonstration, role play, and discussion methods. Each group had weekly two sessions for about 45 min of duration. Sessions were conducted in the free class hours and sometimes 3pm to 4pm. Eight adolescents dropped out (four from experimental and four from control group) during the study for various reasons (dengue fever, long time leave, etc). The components of the intervention are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of anger management program

| Session | Name of the Session | Objectives | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Education on anger | Get to know each other Set group rules To develop understanding about anger and its consequences | Role play |

| Session 2 | ABC analysis of behavior and relaxation training | Enhance awareness about anger and its consequences by using ABC analysis. Identify the triggers which causes anger Introduce the anger diary Impart mindful breathing | Demonstration |

| Session 3 | Modifying anger inducing thoughts | Help the children to recognize the anger producing thoughts. Identify negative automatic thoughts. Modify negative automatic thought. | Discussion |

| Session 4 | Problem solving skill training | Identify the problems related to anger Generate the solutions to the problems related to anger Implement the appropriate solution to the problems related to anger | Role play |

| Session 5 | Assertive communication skill training | Distinguish among aggressive and assertive response, Understand assertive rights and Practice assertive responses to anger arousing situation. | Role play |

| Session 6 | Termination | Preparing for the termination of anger management program and Review of the anger management program. |

Post-intervention assessment

After two months of intervention, post-test assessment was conducted to find out the efficacy of anger management program. One session of education on anger which included anger and its consequences, effects of anger, and demonstration of mindful breathing was conducted to the control group. The steps included in the data collection procedures are summarized in Figure 1.

Data analysis

Analysis was performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 22, and a p-level of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The data was analyzed using frequency distributions, mean and median for the central tendency and range, and standard deviation. Chi-square was done to find the association between the categorical variables. Mann–Whitney U was used to test the homogeneity between experimental and control group. RMANOVA was used to assess the effectiveness of the intervention program. Using RMANOVA reduces type I error. Sphericity assumptions checked by using Mauchly's test, situations where sphericity assumptions violated, Greenhouse–Geisser are reported.

Results

Sociodemographic details

Significant differences were found in religion, education, father's education, and father and mother's occupation of experimental and control groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the school-going adolescents (n=120)

| Variable | Category | School-going adolescents | χ 2 | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Experimental group (n %) | Control group (n %) | Total (n %) | ||||

| Age | 13 yrs | 15 (25) | 19 (32) | 34 (28) | ||

| 14 yrs | 29 (48) | 33 (55) | 62 (52) | 3.48 | 0.324 | |

| 15 yrs | 11 (18) | 5 (8) | 16 (13) | |||

| 16 yrs | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | 8 (6.7) | |||

| Gender | Male | 31 (52) | 32 (53) | 63 (53) | 0.03 | 0.855 |

| Female | 29 (48) | 28 (47) | 57 (47) | |||

| Religion | Hindu | 15 (25) | 19 (32) | 34 (28) | 14.66 | 0.002* |

| Muslim | 29 (48) | 33 (55) | 62 (52) | |||

| Christian | 11 (18) | 5 (8) | 16 (13) | |||

| Others | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | 8 (6.7) | |||

| Education | 8th std | 14 (23) | 40 (67) | 54 (45) | 22.7 | 0.001* |

| 9th std | 46 (77) | 20 (33) | 66 (55) | |||

| Type of school | Government | 20 (33) | 21 (35) | 41 (34) | ||

| Private aided | 20 (33) | 19 (32) | 39 (33) | 0.05 | 0.975 | |

| Private Unaided | 20 (33) | 20 (33) | 40 (33) | |||

| Mother’s education | Illiterate | 19 (32) | 8 (13) | 27 (23) | 7.05 | 0.070 |

| Primary | 16 (27) | 22 (37) | 38 (32) | |||

| High school | 22 (37) | 23 (38) | 45 (37) | |||

| Graduate and above | 3 (5) | 7 (12) | 10 (8) | |||

| Father’s education | Illiterate | 10 (17) | 10 (17) | 20 (17) | ||

| Primary | 29 (48) | 16 (26) | 45 (38) | 7.89 | 0.048* | |

| High school | 18 (30) | 25 (42) | 43 (35) | |||

| Graduate and above | 3 (5) | 9 (15) | 12 (10) | |||

| Mother’s occupation | Professional | 6 (10) | 13 (22) | 19 (16) | ||

| Skilled | 18 (30) | 16 (27) | 34 (28) | 9.82 | 0.020* | |

| Semiskilled | 15 (25) | 4 (7) | 19 (16) | |||

| Home maker | 21 (35) | 27 (45) | 48 (40) | |||

| Father’s occupation | Professional | 8 (13) | 24 (40) | 32 (27) | 11.86 | 0.008* |

| Skilled | 34 (57) | 22 (37) | 56 (47) | |||

| Semiskilled | 17 (28) | 14 (23) | 31 (25.5.) | |||

| Un employed | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | |||

| Type of family | Nuclear | 52 (87) | 51 (85) | 103 (86) | 0.07 | 0.793 |

| Joint | 8 (13) | 9 (15) | 17 (14) | |||

Anger level

No significant difference was found between the pre-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups on the anger level and domains of anger. However, a significant difference was found between their post-test mean scores. The scores of experimental group on the anger level and domains of anger were found to have significantly reduced after the anger management program. On the other hand, the scores of the control group did not significantly change after the anger management program [Table 3].

Table 3.

Pre- and post-test results on anger level and domains of anger among experimental and control groups (n=120)

| Variables | Mean±SD | F | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Experimental group (60) | Control group (60) | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | |||

| Anger level | 111.3±14.4 | 56.48±4.9 | 113.5±17.4 | 113.32±16. | 261.51 | 0.001 |

| VAS | 6.66±1.81 | 4.45±1.37 | 6.73±3.18 | 6.70±1.56 | 17.7 | 0.001 |

| Domains of anger | ||||||

| Intensity | 21.10±4.09 | 12.1±1.9 | 21.53±4.37 | 21.5±4.47 | 97.73 | 0.001 |

| Frequency | 20.16±3.60 | 10.9±1.5 | 20.48±4.01 | 20.5±4 | 106.34 | 0.001 |

| Duration | 14.8±3.68 | 8.5±1.65 | 15.18±4.11 | 15.1±3.82 | 55.349 | 0.001 |

| Mode of expression | 28.9±5.0 | 13.5±1.33 | 29±5.4 | 29.4±5.17 | 187.28 | 0.001 |

| Effects on IPR | 26.5±4.45 | 11.36±1.99 | 26.8±4.8 | 26.8±4.8 | 187.69 | 0.001 |

Outcomes on problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment

No significant difference was found between the pre-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups on the problem solving skills [Table 4]. However, a significant difference was found between their post-test mean scores. The scores of experimental group on the problem solving skills were found to significantly increase after the anger management program. On the other hand, the scores of the control group did not significantly change after the anger management program [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparing the pre-test and post-test results related to problem solving skills, communication skills of the adolescents, adjustment, and domains of adjustment (n=120)

| Variables | Experimental group (n=60) | Control group (n=60) | F | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Pre-test (Mean±SD) | Post-test (Mean±SD) | Pre-test (Mean±SD) | Post-test (Mean±SD) | |||

| Problem solving skills | 27.8±3.8 | 81.66±4.81 | 28.7±4.22 | 28.32±3.78 | 2034.52 | 0.001 |

| Communication skills | 27.9±4.08 | 82.40±3.82 | 29.2±4.04 | 31.8±4.44 | 3003.34 | 0.001 |

| Adjustment | 21.9±3.20 | 28.35±3.76 | 22.10±3.29 | 22.03±3.17 | 52.575 | 0.001 |

| Domains of Adjustment | ||||||

| Home adjustment | 5.18±1.46 | 6.23±1.24 | 5.30±1.45 | 5.21±1.45 | 6.22 | 0.01 |

| School adjustment | 4.26±1.42 | 5.68±1.14 | 4.33±1.45 | 4.36±1.43 | 18.49 | 0.001 |

| Peer adjustment | 4.43±1.88 | 5.71±1.72 | 4.45±1.88 | 4.45±1.82 | 8.163 | 0.005 |

| Teacher adjustment | 4.46±1.17 | 5.70±1.56 | 4.48±1.21 | 4.50±1.21 | 13.5 | 0.001 |

| General adjustment | 3.56±1.25 | 5.01±1.12 | 3.53±1.25 | 3.51±1.20 | 23.78 | 0.001 |

No significant difference was found between the pre-test mean scores of the experimental and control groups on the communication skills [Table 4]. However, a significant difference was found between their post-test mean scores. The scores of experimental group on the problem solving skills were found to significantly increase after the anger management program. On the other hand, the scores of the control group did not significantly change after the anger management program [Table 4].

Similarly, there was no significant difference on adjustment scale between the groups at pre-assessment. There was significant difference between their post-test mean scores. The of scores of experimental group on the adjustment and domains of adjustment were found to significantly reduce after the anger management program, and there was no significant change in the control group [Table 4].

Discussion

The present study reports that anger management program was effective in reducing anger level by improving problem solving skill, communication skills, and adjustment among school-going adolescents. In the current study, six sessions of anger management program were conducted for school-going adolescents. After two months of intervention, post-test assessment was conducted to find out the efficacy of the anger management program. The anger management program was effective in reducing the anger level in the adolescents [Table 3]. Pre-test and post-test mean scores of domains of anger, like intensity, frequency, duration, mode of expression, and interpersonal relationship were significantly different within the experimental and between the experimental and control groups. The present study findings were in concordance with the results of a meta-analysis on effectiveness of school-based anger intervention and programs. It reports that anger management program, which included discussion, role play, practice, modeling, homework, reward for compliance, performance feedback, reward for performance, conducting parent or teacher group sessions, goal setting, visualization/imagery, contracting, and academic tutoring, was effective in reducing anger in school children.[31] The present study results are also supported by another meta-analysis conducted by Smeets et al.[32] (2015) on anger management for adolescents which revealed that anger management skills, social skills training, and assertive communication training had successfully reduced the aggression in adolescents. Furthermore in the current study, it was observed that adolescents enjoyed the experience of role play, demonstration, and re-demonstration. They were actively involved and engaged in all the activities. Students were asked to maintain anger diary and thought diary which made them introspect their thought process related to anger. A review study on mindfulness, relaxation, and anger problem suggests that mindfulness and relaxation can be used as a complementary therapy in intervening with anger disturbances. It reduces impulsive and maladaptive behavior. Mindfulness facilitates the cognitive change and helps in the development of self-regulatory ability.[33] In the present study, relaxation was practiced in each session. Adolescents reported that it calms their mind and increases their attention in studies. Adolescents were encouraged to practice relaxation in the home setting.

The mean scores of problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment were significantly improved. These findings were statistically significant within the experimental and between the experimental and control groups [Table 4]. The results of the study showed that anger management program was effective in increasing the problem solving skills, communication skills, and adjustment, thereby reducing the anger level in the adolescents. This finding is consistent with results of a meta-analysis on anger management for adolescents which included anger management, social skills, problem solving skills, and family communication. These sessions were effective in reducing aggression in adolescents.[34] Another study conducted among adolescents reported that anger management training had a high and stable effect on reducing female teenagers’ aggression. Furthermore, group discussion program oriented toward communicative skills had reduced aggression in the experimental group significantly.[35]

The present study findings are also similar to the findings of study which evaluated the effectiveness of anger management intervention for school children which included changing thinking patterns, developing social problem solving skills or self-control, and managing anger, learning constructive behavior for interpersonal interactions, including communication skills, conflict management, and behavioral strategies.[36] In the present study, the experimental group showed significant decrease in anger level. The findings of the current study are in concordance with the finding of a study on anger management training for high school students. The results showed that aggression clearly decreased among students who participated in the anger management skills training group.[37] Similar findings were reflected in another study. They which included anger education program. They reported an increase in anger control and communication skill.[38]

The present study finding shows that the anger management program increases the adjustment of adolescents’ at their home, with peer, school, teacher, and their general adjustment (Table. 4). Anger management training was found to help adolescents to improve their social adjustment.[39]

The purpose of the present study is to create awareness in the adolescents that they can identify the triggers for their anger and manage their anger in a healthy way. The intervention components have shown their effectiveness in the chosen variables of the study. The other component in this anger management program is modifying the anger-provoking thoughts, where the student experiences negative thoughts during the times they feel angry. These negative thoughts can occur from misunderstandings, or a lack of coping skills, or social skills. The present anger management program equips the adolescents in problem solving skills and communication skills, thereby enabling the adolescent to solve problems in better way and resolve the anger-related problems in their lives. Each of these sessions which dealt with anger in adolescents was successful and empowered them with adequate skills in managing their anger in a healthy way.

Implication

Anger management skill training is essential for adolescents. Therefore, the teachers, school administrators, school counselors, and who work with these adolescents should be trained. Periodically conducting anger management program increases the emotional regulations in the students, thereby healthy school environment can be maintained. Nurses can liaison with the teachers to design programs to intervene anger problems in children. Using the anger management program, nurses can incorporate several strategies in identifying and intervening children with anger problem and help them to manage their anger in healthy way. This can reduce the risk of child becoming violent and delinquent later in life.

Limitation and recommendation

Majority of the adolescents of this study belong to middle or low-income groups, urban and state board schools; hence, generalization to entire adolescent population may be limitation of this study. A major limitation is there was no screening for other mental health issues except for ADHA and CD. Childhood depression can cause anger outbursts, and likewise other disorders like DMRD, IED, psychosis, etc., Follow-up assessment was not conducted, and hence, it is difficult to say if the effects of the anger management programs were maintained for a longer duration.

Conclusion

This study examined the effectiveness of anger management program. Strategies used in the anger management program were very effective in reducing the anger level by improving problem solving skill, communication skill, and adjustment among school-going adolescents. The anger management program developed and implemented in the study can be used in the schools to teach the adolescents to manage their emotions constructively and prevent destructive behaviors.

Contributors

The first author (AS) conceptualized the study with the help of second and third authors. AS carried out the data collection and analysis. GR, BB, and MM helped in data analysis and interpretation. First draft of the paper was written by AS. GR, MM, and BB reviewed the drafts and approved the final draft.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the support and cooperation of the schools that participated in the study. We thank all the participants for giving valuable information.

References

- 1.Lamb JM, Puskar KR, Sereika S, Patterson K, Kaufmann JA. Anger assessment in rural high school students. J Sch Nurs. 2003;1:30–40. doi: 10.1177/10598405030190010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui L, Morris AS, Criss MM, Houltberg BJ, Silk JS. Parental psychological control and adolescent adjustment: The role of adolescent emotion regulation. Parent Sci Pract. 2014;14:47–67. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2014.880018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Down R, Willner P, Watts L, Griffiths J. Anger management groups for adolescents: A mixed-methods study of efficacy and treatment preferences. Clin. Child Psychol. 2011;16:33–52. doi: 10.1177/1359104509341448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoogsteder LM, Stams GJJM, Figge MA, Changoe K, van Horn JE, Hendriks J, et al. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of individually oriented cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT) for severe agressive behavior in adolescents. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2015;26:22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez VA, Emmer ET. Influences of beliefs and values on male adolescents’ decision to commit violent offenses. Psychol Men Masc. 2002;31:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tusaie K, Puskar K, Sereika SM. A predictive and moderating model of psychosocial resilience in adolescents. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39:54–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokhber T, Masjedi A, Bakhtiari M. A comparison of the effectiveness of social skills training and anger management on adjustment of unsupervised girl adolescents. Behav Brain Sci. 2016;6:530–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Çam S, ve Tümkaya S. Kişilerarası problem çözme envanteri’nin (KPÇE) geliştirilmesi: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi. 2007;28:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pumble. The barriers to effective communication. Available from: httpp//pumble.com .

- 10.Flanagan R, Allen K, Henry DJ. The impact of anger management treatment and rational emotive behavior therapy in a public school setting on social skills, anger management, and depression. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther. 2010;28:87–99. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollock KM, Kymissis M. The future of adolescent group therapy. An analysis of historical trends and current momentum. J Child Adolesc Group Ther. 2001;11:5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, DiGiuseppe RA. Principles of empirically supported interventions applied to anger management. Couns Psychol. 2016;30:262–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yılmaz D, Ersever OG. The effects of the anger management program and the group counseling on the anger management skills of adolescents. Psychol. 2015;4:16–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feindler EL, Engel EC. Assessment and intervention for adolescents with anger and aggression difficulties in school settings. Psychol Sch. 2011;48:243–53. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candelaria AM, Fedewa AL, Ahn S. The effects of anger management on children's social and emotional outcomes: A meta-analysis. Sch Psychol Int. 2012;33:596–614. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arslan C, Adıgüzel G. Investigation of university students’ aggression levels in terms of empathic tendency, self-compassion and emotionak expression. Eur J Educ. 2018 doi: 10.46827/EJES.V0I0.1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blake CS, Hamrin V. Current approaches to the assessment and management of anger and aggression in youth: A review. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2007;20(4):209–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2007.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey JR. The design of an anger management program for elementary school students in a self- contained classroom. 2004. (Doctoral dissertation. The State University of New Jersey [Google Scholar]

- 19.Şahin H. Theoretical foundations of anger control. Süleyman Demirel University, Journal of the Burdur Faculty of Education. 2005;6(10):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharp SR. Effectiveness of an Anger Management Training Program Based on Rational Emotive Behavior Theory (REBT) for Middle School Students with Behavior Problems. PhD diss., University of Tennessee. 2003. Available from: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss .

- 21.Anjanappa S, Govindan R, Munivenkatappa M. Anger management in adolescents: A systematic review. Indian J Psy Nsg. 2020;17:51–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Society of Psychiatric -Mental Health Nurse (ISPN). Prevention of Youth Violence. 2001. Available from: https://www.ispn-psych.org/assets/docs/3-01-youth-violence.pdf .

- 23.Mahon NE, Yarcheski A, Yarcheski TJ, Hanks MM. A meta-analytic study of predictors of anger in adolescents. Nurs Res. 2010;593:178–84. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dbba04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puskar KR, Ren D, McFadden T. Testing the “teaching kids to cope with anger” youth anger intervention program in a rural school-based sample. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2015;36:200–8. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.969390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hernawati R, Soejowinoto The predictors of indonesian senior high school students’ anger at school. J Educ Pract. 2015;6:108–19. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pullen L, Modrcin MA, McGuire SL, Lane K, Kearnely M, Engle S. Anger in adolescent communities: How angry are they? Pediatr Nurs. 2015;41:135–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutt D, Pandey GK, Pal D, Hazra S, Dey TK. Magnitude, types and sex differentials of aggressive behaviour among school children in a rural area of West Bengal. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38:109–13. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.112447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barkman S, Machtmes K. Communication evaluation scale. CYFAR project. 2002:2012–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sukhodolsky DG, Smith SD, McCauley SA, Ibrahim K, Piasecka JB. Behavioral interventions for anger, irritability, and aggression in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2016;26:58–64. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sukhodolsky DG, Kassinove H, Gorman BS. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for anger in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004;9:247–69. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gansle KA. The effectiveness of school-based anger interventions and programs: A meta-analysis. J Sch Psychol. 2005;43:321–41. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smeets K, Leeijen A, Molen M, Scheepers F, Buitelaar J, Rommelse NN. Treatment moderators of cognitive behavior therapy to reduce aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:255–64. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright S, Day A, Howells K. Aggression and violent behavior mindfulness and the treatment of anger problems. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14:396–401. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fossum S, Handegard B, Adolfsen F, Vis SA, Wynn R. A meta-analysis of long-term outpatient treatment effects for children and adolescents with conduct problems. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016;25:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karimi Y. The effect of anger management training on Tehran high school female teenagers’ aggression aged 15-18. Soc. Psychol. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. School-based interventions for aggressive disruptive behavior—update of a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:130–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valizadeh S, Davaji RBO, Nikamal M. The effectiveness of anger management skills training on reduction of aggression in adolescents. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:1195–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little TD, Henrich CC, Jones SM, Hawley PH. Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behaviour. Int J Behav Dev. 2003;27:122–31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mohammadi A, Kahnamouei SB, Allahvirdiyan K, Habibzadeh S. The effect of anger management training on aggression and social adjustment of male students aged 12-15 of shabestar schools in 2008. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:1690–3. [Google Scholar]