Abstract

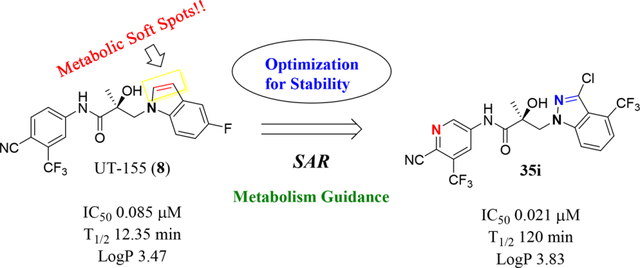

A major challenge for new drug discovery in the area of androgen receptor (AR) antagonists lies in predicting the druggable properties that will enable small molecules to retain their potency and stability during further studies in vitro and in vivo. Indole (compound 8) is a first-in-class AR antagonist with very high potency (IC50 = 0.085 μM) but is metabolically unstable. During the metabolic studies described herein, we synthesized new small molecules that exhibit significantly improved stability while retaining potent antagonistic activity for an AR. This structure–activity relationship (SAR) study of more than 50 compounds classified with three classes (Class I, II, and III) and discovered two compounds (32c and 35i) that are potent AR antagonists (e.g., IC50 = 0.021 μM, T1/2 = 120 min for compound 35i). The new antagonists exhibited improved in vivo pharmacokinetics (PK) with high efficacy antiandrogen activity in Hershberger and antiandrogen Enz-Res tumor xenograft models that overexpress AR (LNCaP-AR).

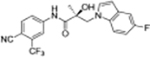

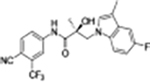

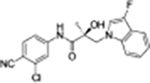

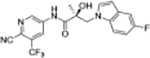

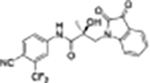

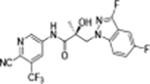

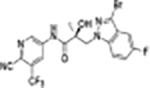

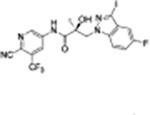

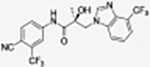

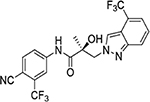

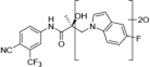

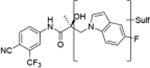

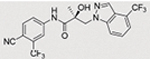

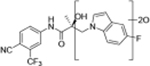

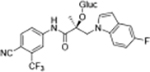

Graphical Abstract:

1. INTRODUCTION

Human androgen receptors (ARs) and the development of antiandrogenic ligands are principal drivers for diseases characterized by AR abnormality, including prostate cancer (PC).1 The number of PC patients in the United States and worldwide continues to increase.2 As a key molecule in the progression of PC, AR is a critical therapeutic target for developments of treatments for castration-resistant PC (CRPC).3 Despite the FDA approval of antiandrogens for treatment of PC, the emergence of antiandrogen-resistant forms of PC remains a challenge to this therapeutic scheme that will require innovative approaches to solve.

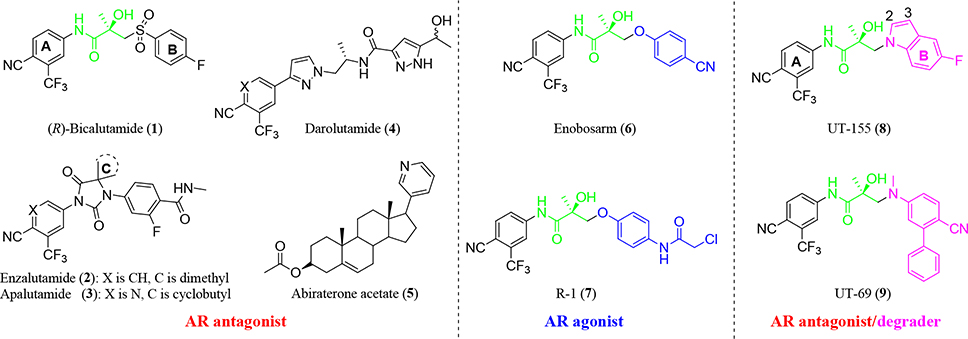

AR is a steroid receptor transcription factor that is activated by androgenic hormones such as testosterone (T) and 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). The three main functional AR domains are the N-terminal domain that contains activation function-1 (AF-1), the DNA-binding domain that binds to the promoters and enhancers that regulate AR-dependent genes and contains the hinge region, and the ligand-binding domain (LBD) that contains AF-2 and binds to endogenous androgens.4 Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) blocks the endogenous testicular production of androgens and effectively lowers serum T to castration levels. ADT has been the standard of care for advanced PC and has been used for combination therapy with antiandrogens (direct AR antagonists) such as bicalutamide, enzalutamide, apalutamide, darolutamide, and abiraterone acetate,5–10 as shown in Figure 1. Thus far, antiandrogens have typically been diaryl compounds with two aromatic rings connected by a propanamide segment (Figure 1, compounds 1–4) that can be linear (Figure 1, compounds 1,4) or cyclized into a hydantoin (Figure 1, compounds 2–3). When members of our group modified the B-ring, we discovered a class of nonsteroidal tissue-selective androgen receptor modulators (SARMs)11–20 that function as tissue-selective agonists (Figure 1, compounds 6–7). In contrast, inclusion of a basic nitrogen atom to replace the thioether or ether group in the SARM compounds resulted in a new class of compounds that exhibit pan-antagonism and selective androgen receptor degrader (SARD) activity (Figure 1, compounds 8–9).13,21–24

Figure 1.

Known small-molecule AR ligands. These include nonsteroidal and steroidal antagonists (left panel), AR agonists (middle panel) and initial AR antagonists and AR degraders (right panel).

The first-in-class AR antagonist UT-155 (Figure 1, compound 8), unlike enzalutamide (Figure 1, compound 2), contained an indolyl group in place of the B-ring and exhibits exceptionally potent AR degrader activity (IC50 = 0.085 μM for UT-155 and 216 μM for enzalutamide).13,21

The discovery that UT-155 also contained a site that was metabolically labile (T1/2 = 12.34 min) in human liver microsomes (HLM) led us to investigate the 2- and 3-positions of the indole B-ring in an effort to develop compounds with improved antimitotic effects and reduced untoward effects such as metabolic instability. Generally, strategies for reducing the metabolism of a drug include reducing lipophilicity, modulating steric and electronic factors, altering stereochemistry, and introducing conformational constraints during the drug discovery process.25 However, the knowledge from our initial biological evaluation of the B-rings from the different indole types (Table 1) suggested that since the 2- and 3-positions on the indole ring were possible metabolic weak spots, they might be most amenable to modification.

Table 1.

Initial Biological Evaluation of Indole AR Analogues

| ID | Structure | Binding (Ki)/Transactivation (IC50) (μM) | SARD Activity (% degradation) | Metabolic Stability in Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLM)f | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Ki (DHT = 1 nM)a | IC50b | Full Lengthc,d (LNCaP)@1μM | Splice Variantc (22RVl)@10μM | T1/2 (min) | CLint (mL/min/mg) | ||

|

| |||||||

| 8 13 |

|

0.267 | 0.085 | 76 | 87 | 12.35 | 5.614 |

| 19a 13 |

|

0.547 | 0.157 | 32 | 69 | 21.77 | 3.184 |

| 19b |

|

0.332 | 0.045 | 68 | 62 | 9.29 | 7.46 |

| 20 |

|

0.757 | 0.027 | 57, 97d | N/Ae | 14.6 | 4.70 |

| 26 |

|

>10 | >10 | 0 | 0 | N/Ae | N/Ae |

AR binding was determined by competitive ligand binding, as described.13,21,23,24 The recombinant ligand binding domain (LBD) of wildtype AR was incubated with 1 nM [3H]-mibolerone and the candidate SARD compound (1 pm – 100 μM) or 1 nM DHT; following incubation, the complex was precipitated with hydroxyapatite and washed, and the bound radioactivity was eluted and quantified on a scintillation counter. SigmaPlot software was used to determine the resulting inhibitory constant (Ki) for each compound relative to 1 nM DHT.

Inhibition of AR transactivation was determined by transfecting human embryonic kidney HEK-293 cells with full-length wildtype AR, GRE-LUC, and CMV-renilla luciferase as a transfection control. Twenty-four h later, the cells were treated for 24 h with 0.1 nM agonist R1881 or varying doses of the indicated antagonist compounds (1 pM to 10 μM in log units). After incubation, the cells were collected, lysed, and analyzed by luciferase assay, as described.13,21

SARD activity was determined as a function of AR protein levels in cultured cells, as described.13,21,22 Cells used were of the androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line LNCaP that expresses full-length (FL) AR or the xenograft-derived human prostate carcinoma epithelial cell line 22RV1 that expresses a c-terminally truncated splice variant (SV) of AR (AR-V7). Cells were treated for 24 h with the indicated doses of the candidate antagonist compounds in the presence of 0.1 nM agonist R1881. Cells were harvested, lysed, and FL or SV AR was detected by immunoblot with AR-N20 antibodies directed against the AR N-terminal domain (NTD). Blots were stripped and reprobed with antibodies specific for the cellular protein actin as an internal control. FL and SV AR species were quantified and normalized to actin signals.

SARD activity of compound 20 against FL AR was evaluated in LNCaP cells at 10 μM concentration.

SARD activity of compound 20 against SV AR in 22RV1 cells was not available (N/A).

The metabolic stability (half-life, hepatic clearance) of each compound was determined by incubation for varying time periods with mouse liver microsomes (MLM) and cofactors for phase I and phase II metabolism, as described in the Experimental section in Supporting Information. T1/2 (h) after oral administration in humans as previously reported.13 CL (mL/h/kg) after oral administration in humans as previously reported.23,24

In comparing metabolic stability of the 2,3-unsubstituted indole 8 (T1/2 = 12.35 min showed in Table 1) with substituted 3-position groups, effects on the 3-position introducing electron withdrawing group (EWG, e.g., compound 19a; T1/2 = 21.77 min in Table 1) or electron donating group (EDG, e.g., compound 19b; T1/2 = 9.29 min) showed different stability in the mouse model by possibly blocking the metabolism shown in Figure 3. It was observed in our initial test in Table 1 that the EWGs and EDGs on the 3-position of the indole core can change the stability trend for our indole derivatives.

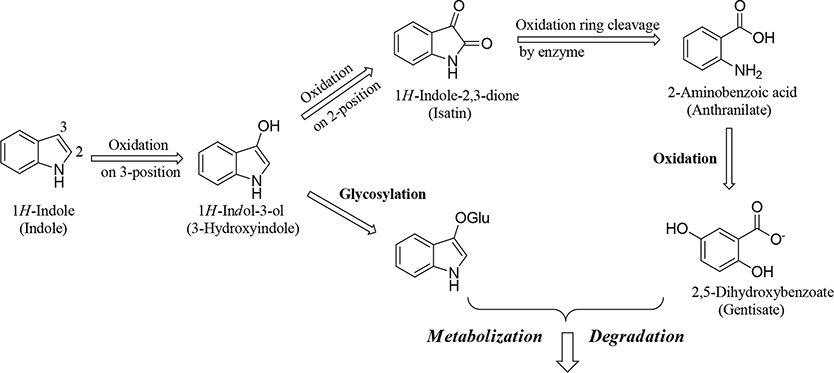

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism for in vivo and/or in vitro metabolic degradation of an indole.33,34 Oxidation at the 3-position of the indole ring and its subsequent glycosylation results in its degradation. Alternatively, oxidation at the 3-position and subsequently at the 2-position leads to oxidative cleavage of the five-membered pyrrole constituent of the heterobicyclic ring by a cellular enzyme. Further oxidation results in degradation of the ring.

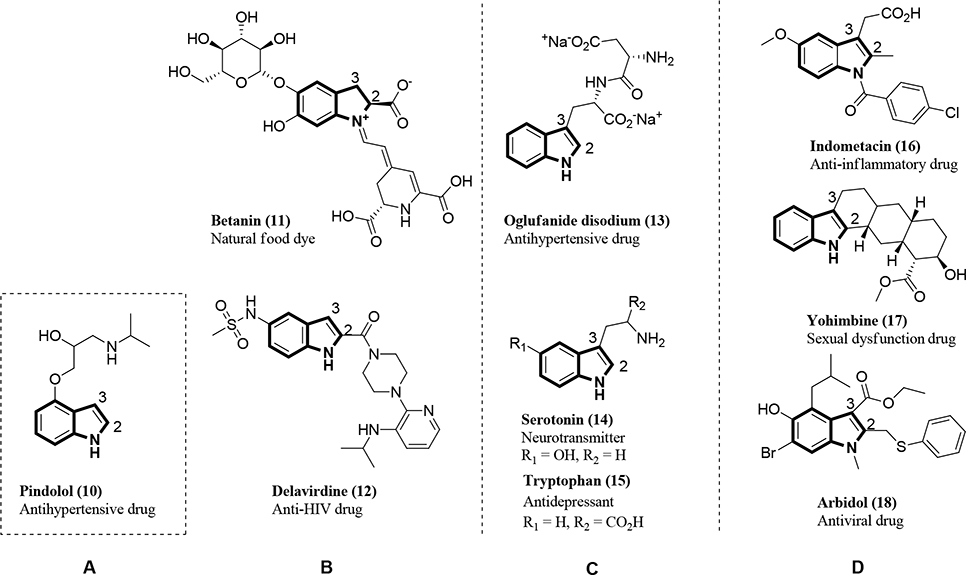

Indoles are one of the main functional groups found in natural and synthesized drugs, as shown in Figure 2. After our structural analysis of known indoles, we categorized them into four types (A, B, C, and D) based on the substitutions added to the 2- and/or 3-positions of the core indole portion. Indole groups of Type A are unsubstituted, i.e., have no substituents at the 1-, 2-, or 3-positions of the indole ring (depicted by the NH group at position 1, Figure 2A) and are typified by pindolol26 (Figure 2, compound 10), an antihypertensive drug that functions as an antidepressant. Indoles of Type B have a substituent only at the 2-position of the core indole (Figure 2B). These include betanin27 (Figure 2B, compound 11), which lowers blood pressure, and delaviridine28 (Figure 2B, compound 12), a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Indoles of Type C have a substituent only at the 3-position of the core indole (Figure 2C). These are typified by the antihypertensive drug oglufanide disodium29 (Figure 2C, compound 13), the neurotransmitter serotonin29 (Figure 2C, compound 14), and the antidepressant drug tryptophan29,30 (Figure 2C, compound 15). Finally, indoles of Type D are disubstituted at both the 2- and 3-positions of the core indole (Figure 2D). These are typified by the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin4 (Figure 2D, compound 16), the sexual dysfunction drug yohimbine31 (Figure 2D, compound 17), and the broad-spectrum antiviral drug Arbidol32 (Figure 2D, compound 18).

Figure 2.

Natural bioactive alkaloids (compounds 11, 14–15) and synthesized drugs (compounds 10, 12–13, and 16–18) containing an indole nucleus that is (A) unsubstituted; (B) substituted at the 2-position; (C) substituted at the 3-position; or (D) substituted at both the 2- and 3-positions.

The mechanism for the in vivo and in vitro metabolism of indole groups proposed by Claus et al. (1983), shown schematically in Figure 3, features oxidization of the indole ring at the 3-position to yield an indoxyl group, followed by either glycosylation at the 3-position, which targets the molecule for degradation, or oxidation at 2-position to yield an isatin group that is subject to oxidative cleavage of the five-membered pyrrole constituent of the heterobicyclic ring; additional oxidation results in the cleavage of the indole ring.33,34 Herein, we report a metabolism-guided approach that optimized substituents in the 2- and 3-positions on the indole group in the B-ring of UT-155 (Figure 1, compound 8) to yield metabolically stable indole analogues that exhibit significant AR antagonist activity. In this study, we sought to produce new molecules that will potently inhibit AR with binding stronger than 0.200 μM and high metabolic stability (i.e., longer half-life (T1/2) than that of UT-155 (12.35 min) and optimally >60 min).

Chemistry.

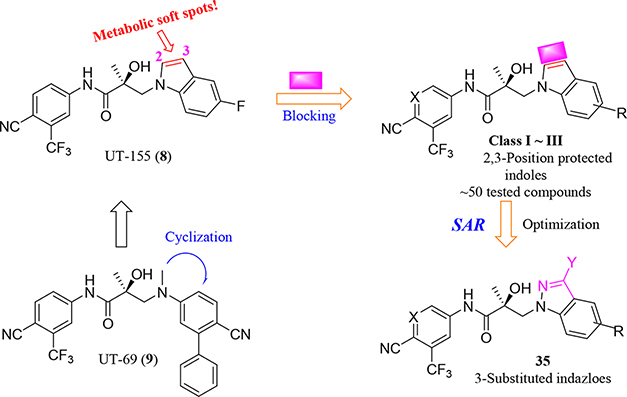

Design Strategy and Initial Test.

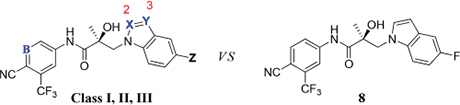

We performed a structure–activity relationship (SAR) study, shown schematically in Figure 4, with which to explore potential metabolic sites at the 2- and 3-positions of the indole ring, using as our starting point the indole of UT-155 (Figure 1, compound 8) developed from the amine UT-69 (Figure 1, compound 9).13 To further optimize UT-155 (compound 8) and lengthen its short metabolic half-life, we first protected the 2- and 3-positions of its indole portion with different blocking modes using the following Class I–III changes:

Figure 4.

Design and SAR study for metabolically stable 2,3-substituted indoles.

Class I: bulky/hard modes with 2- and 3-positioned indoles (called as carbazole (compounds in series 27) and benzotriazole derivatives (compounds in series 34).

Class II: 2- or 3-positioned indoles that are derivatives of benzimidazole (called “3N-indole”, compounds in series 31) and indazole (called as “2N-indole”, compounds in series 32).

Class III: 3-substituted 2N-indoles (called “3-substituted indazoles”) that led to substituted indazole compounds (series 35).

Using this strategy (Figure 4), we designed and synthesized more than 50 new chiral AR indoles using the three different blocking methods (Class I, II, and III); their structures are summarized in Table 2. We subsequently assayed their metabolic stability and potency.

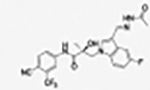

Table 2.

Summary of Structures of Designed Molecules (Class I, II, and III)

| ID | Structure | ID | Structure | ID | Structure | ID | Structure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| 27a |

|

31a * |

|

31n |

|

35a |

|

||||

| 27b |

|

31b * |

|

31o |

|

35b |

|

||||

| 27c |

|

31c |

|

31p |

|

35c |

|

||||

| 27d |

|

31d * |

|

31q |

|

35d |

|

||||

| 27e |

|

31e * |

|

31r |

|

35e |

|

||||

| 34a |

|

31f * |

|

31s |

|

35f |

|

||||

| Class I | 34b |

|

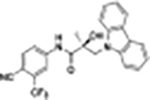

Class II | 31g * |

|

Class II | 32a § |

|

Class III | 35g |

|

| 34c |

|

31h |

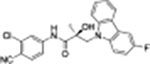

|

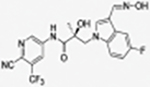

32b § |

|

35h |

|

||||

| 34d |

|

31i |

|

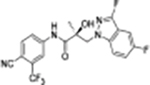

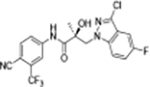

32c § |

|

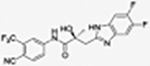

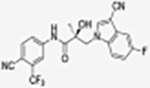

35i |

|

||||

| 34e |

|

31j |

|

32d § |

|

35j |

|

||||

| 34f |

|

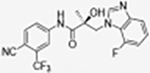

31k |

|

35k |

|

||||||

| 34g |

|

31l |

|

||||||||

| 34h |

|

31m |

|

||||||||

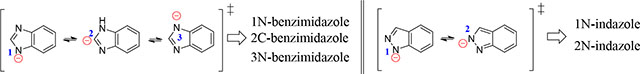

The compounds contained regioisomers of benzimidazoles in indole B-rings (31a and 31b, 31d and 31e, 31f and 31g, i.e., 1N-, 2C-, or 3N-substituted).

Regioisomers of indazoles in indole B-rings (32a and 32b, 32c and 32d, i.e., 1N- or 2N-substituted).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

2.1. Chemistry.

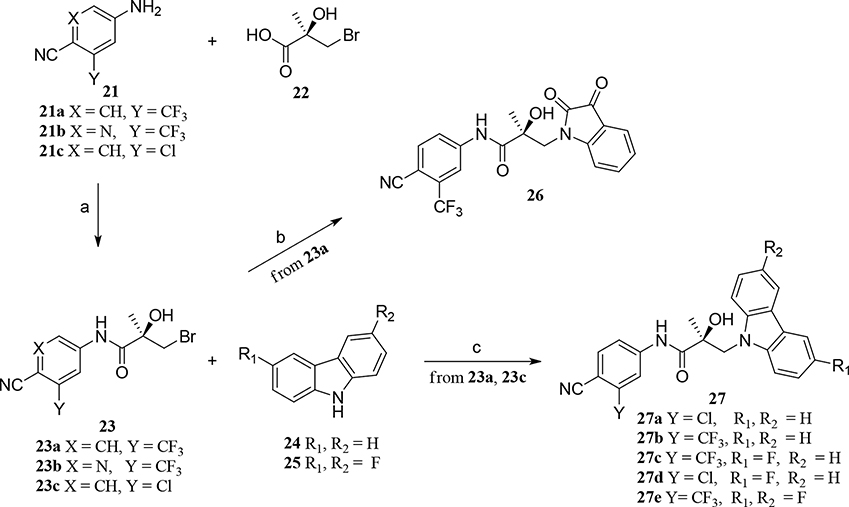

We will begin by describing the preparation of newly designed molecules of Classes I, II, and III. Using methods described in the literature,11,13 we coupled the bromide compound 23 with various substituted heterocyclic compounds (carbazoles, benzimidazoles, substituted indoles, benzotriazoles, or indazoles; i.e., compounds 25, 28, 29, or 30) in the presence of various bases to produce compounds 27, 31, 32, 34, and 35, as shown in Schemes 1, 2, and 3. Notably, for Class I, sodium hydride (NaH) was effectively used to activate carbazoles in compound 25 and reacted with related bromides in compound 23 to produce good yields (>80%) of the targeted carbazole molecules 27a–e, following the preparation of the bromoacid compound 22 and the subsequent aniline compound 21 in the procedure we described previously,11,13 as shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Generic Synthesis of Class I Compounds 27a–ea.

aReagents and conditions: (a) i. SOCl2, THF, 0 °C; ii. Et3N; (b) isatin, K2CO3, DMF, room temperature (RT); (c) NaH, THF, 0 °C to RT.

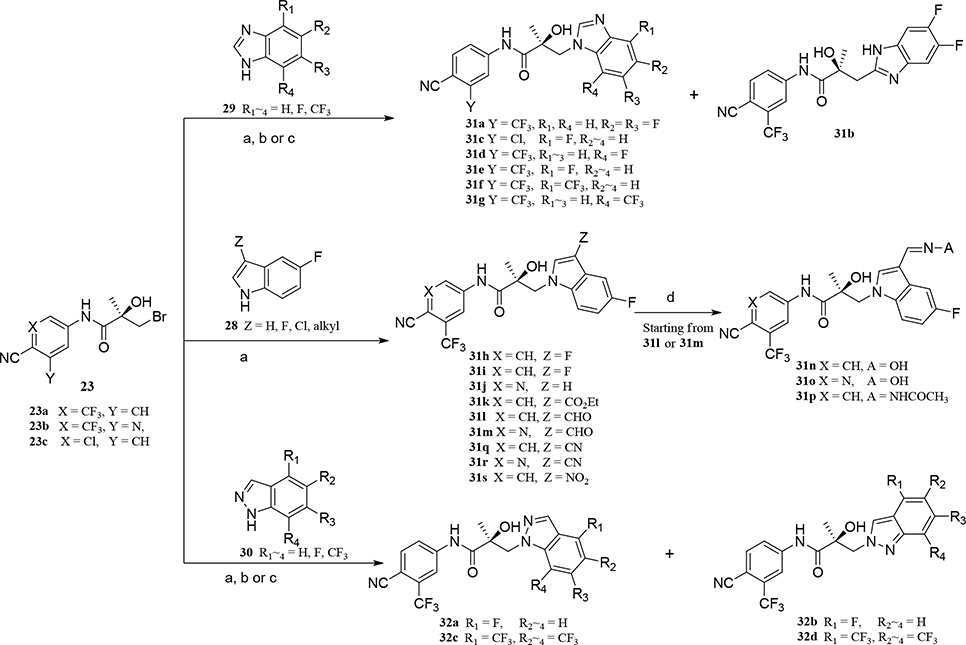

Scheme 2. Generic Synthesis of Class II (Compounds 31a–s and 32a–d)a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) NaH, THF, 0 °C to RT; (b) K2CO3, DMF, 80 °C; (c) bis(trimethylsilyl)-amide, THF, −78 °C ~ RT; (d) NH2OH or NH2NHCOCH3, pyridine, RT.

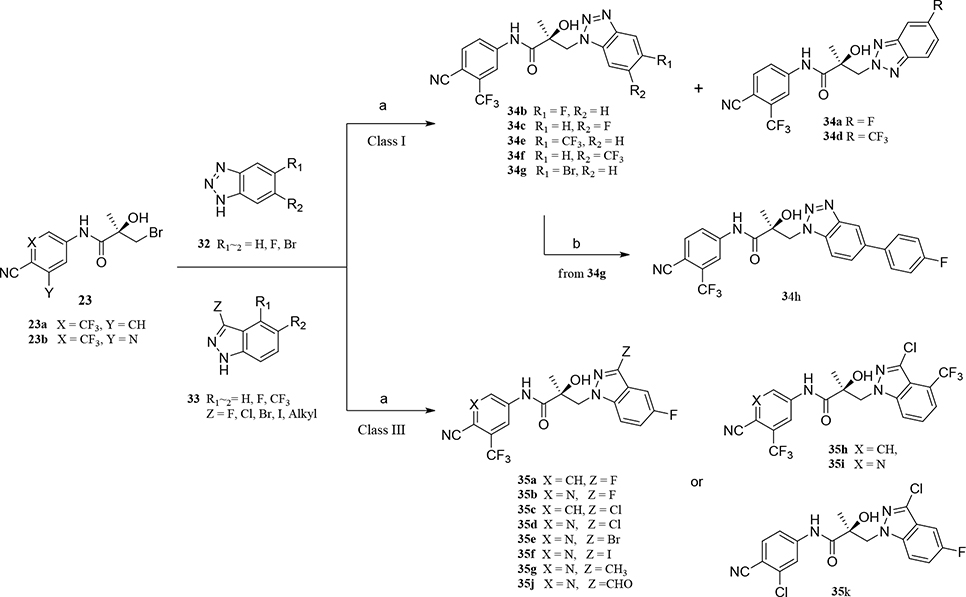

Scheme 3. Generic Synthesis of Class I (34a–h) and III (35a–g) Compoundsa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) compound 32 or 33, NaH, THF, 0 °C to RT; (b) Pd(PPh3)3, Na2CO3, phenylboronic acid, EtOH/H2O, reflux.

For Class II, compounds 31a–g were prepared using three different bases, namely NaH in THF (Method A), K2CO3 in DMF (Method B), or bis(trimethylsilyl)amide in THF (Method C), as shown in Scheme 2. Benzimidazole derivatives of compounds 31a–b were prepared by NaH-mediated activation in general Method A (see Experimental Section) and purified with their regiospecific isomers by flash column chromatography, followed by confirmation of the presence of both regiospecific isomers (1N-alkylated benzimidazole B-ring for compound 31a and 2C-alkylated benzimidazole B-ring for compound 31b). A measurement of N- and C-alkylation yielded a 1:2 ratio (i.e., 12.6% for compound 31a: 28.4% for compound 31b, with a total yield of 41% via Scheme 2).

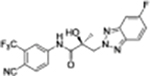

1N-Alkylation of compound 31c was predominantly produced using potassium carbonate (K2CO3) in DMF at 80 °C (Method B) to couple the bromide compound 23c with 4-fluorobenzimidazole (compound 29 with R1 = F, Scheme 2) with 63% yield. Pairs of regioisomers (compounds 31d–e and 31f–g) were obtained by treating the corresponding benzimidazole compound 29 with lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide and bromide compounds 23a–c followed by separation using column chromatography. Using NaH in THF solution,13,35 the 3-substituted indole compound 28 underwent N-alkylation with compound 23 (23a or 23b) to produce the desired indolyl compounds 31h–s in reasonable yields (<94%) via Scheme 2. The addition of nucleophilic hydroxylamine (or acetohydrazide) to aldehyde compounds 31l or 31m in basic conditions produced the designed compounds 31n–p by Method D (see Experimental Section). For indazole compounds 32a–d, the reaction was conducted using bases (i.e., lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide for compounds 32a–b or NaH for compounds 32c–d), through N-substitution (i.e., 1N- and 2N- of an indazole) of indazole compound 30 with bromide compound 23 generated the pairs of regiospecific isomers (1N- and 2N-indazole compounds 32a–b and 32c–d, respectively, which were subsequently isolated by flash column chromatography. 2D NMR was used to identify the isomer pairs of benzimidazoles (compounds 31a–b and 31f–g) and indazoles (compounds 32a–b and 32c–d), as shown in Figure S1 and S2 of the Supporting Information section. The structures of the regiospecific isomers of the benzimidazoles (compounds 31a–b and 31f–g) and indazoles (compounds 32a–d) are summarized in Table 3.

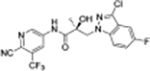

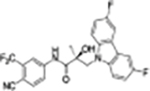

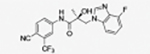

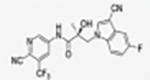

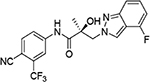

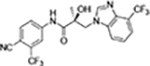

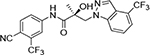

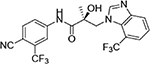

Table 3.

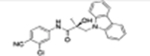

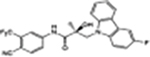

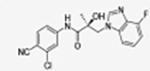

Regiospecific Isomers of Benzimidazole and Indazole in B-Ring Derivatives

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| ID | Structure | Represented name | ID | Structure | Represented name |

|

| |||||

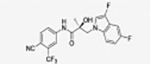

| 31a |

|

1N-benzimidazole | 32a |

|

1N-indazole |

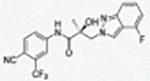

| 31b |

|

2C-benzimidazole | 32b |

|

2N-indazole |

|

| |||||

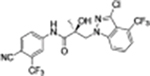

| 31g |

|

1N-benzimidazole | 32c |

|

1N-indazole |

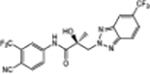

| 31f |

|

3N-benzimidazole | 32d |

|

2N-indazole |

In Scheme 3, several benzo-triazole/3-substituted indazole derivatives (compounds 34a–g and 35a–j, Class I and III) were prepared by Method A, as reported previously.13 A Suzuki reaction that entailed carbon–carbon cross-coupling36 of a palladium(0) complex reaction of compound 34g with phenyl boric acid produced the corresponding compound 34h in good yield (90%). For the 3-substituted indazole compound 35 series, activation of several 3-substituted indazole compounds of 33 with sodium hydride produced the desired 3-substituted indazoles 35a–j by Method A, as shown in Scheme 3.

2.2. Separation, Determination and Two Sets of Isomers (Benzimidazoles and Indazoles) in the B-Ring (Class II).

We successfully prepared three sets of regiospecific isomers (compounds 31a–b, 31d–e, and 32a–d) by synthetic Methods A or C and purified the sets of the isomers by flash column chromatography to produce each isomer of the benzimidazoles (isomers 31a–31b and 31d–31e) and the indazoles (isomers 32a–32b and 32c–32d).

The regioisomers of 1N- or 2C-benzimidazoles (compounds 31a–31b), 1N- or 3N-benzimidazoles (compounds 31d and 31e; 31f and 31g), and 1N- or 2N-indazoles derivatives (32a and 32c; 32b and 32d) were purified with flash column chromatography to produce each pair of isomers shown in Table 3 and Scheme 2. LC mass spectroscopy and 2D NMR were used to identify the separated sets of each isomer (31a–b, 31d–e, and 32a–d), as shown in Figures S1 and S2. Each B-ring isomer substituted with benzimidazole or indazole exhibited different retention times in HRMS analysis (Figure S1, panel B for 31f and 31g and Figure S1, panels D and F for compounds 32a–32d), while 2D NMR identified the individual chemical structures by their different NOE effects (Figure S2, panels A–F). In our effort to further investigate the B-ring analogues including the benzimidazoles and indazoles produced by SAR (Figure 4), we next examined their bioactivity in vitro.

2.3. Overview of in Vitro Antagonism of AR Biological Activity (Class I–III Derivatives).

We first examined the effect of the B-ring substitutions (in Class I–III) on their ability to antagonize transcription of a luciferase reporter gene under control of a glucocorticoid response element (GRE-LUC) in the presence of AR agonist R1881 (IC50) in African green monkey COS cells.

The pharmacological activities of Class I, II, and III derivatives were examined in vitro using not only the transactivation assay for AR antagonism described here but also assays of AR binding affinity and degradation, as described in the legend of Table 4 (for Class I) and Table 5 (for Class II and III). The degradation assays were performed in two cell lines, the androgen-sensitive human prostate adenocarcinoma cell line LNCaP that expresses full-length (FL) AR and the xenograft-derived human prostate carcinoma epithelial cell line 22RV1 that expresses a c-terminally truncated splice variant (SV) of AR (AR-V7). The results obtained from AR affinity binding, AR antagonism, and AR degradation assays performed with Class I derivatives (indoles substituted at the 2- and 3-positions, compounds 27a–e and 34a–h) are shown in Table 4. The bulky carbazoles, compounds 27a–e, exhibited consistent AR binding affinity (>0.810 μM for compound 27e) and degradation of FL AR in LNCaP cells (<51% at 1 μM for compound 27e) and in 22RV1 cells (<87% at 10 μM for compound 27a), as shown in Table 4. The AR transactivation (IC50) of compound 27b (0.871 μM) was not enhanced relative to parental indole compound 8 (0.085 μM) or enzalutamide (compound 2; 0.216 μM). For the triazole derivatives 34a–h, in the AR transactivation assay of antagonistic activity (IC50), the 2N-substituted triazole (compound 34a) exhibited similar transactivation (0.277 μM) to that of enzalutamide (compound 2; 0.216 μM). Finally, in the AR degradation assay, the triazole derivatives like compound 34a degraded FL AR in LNCaP cells (70% for 34a), but compounds 34a and 34b were unable to degrade the AR-7 AV mutant in 22RV1 cells (Table 4).

Table 4.

In Vitro Pharmacological Activity of Class I Derivatives (Compounds 27a–e and 34a–h)a

| Class I | Binding (Ki)/Transactivation (IC50) (μM) | SARD Activity (% degradation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| (ID) | Ki (DHT=1nM)b | IC50b | Full Lengthb (LNCaP) @1 μM | Splice Variantb (22RV1) @10 μM | |

| 8 | 0.267 | 0.085 | 76 | 87 | |

| 27a | 0.091 | 1.079 | 19, 87e | 87 | |

| 27b | 0.729 | 0.871 | 48 | 60 | |

| 27c | 0.194 | 0.991 | 20 | 29 | |

| 27d | 0.249 | 1.243 | 38 | 0g | |

| 27e | 0.810 | 1.025 | 51 | -f | |

| 34a | 3.615 | 0.277 | 70 | 0g | |

| Class I | 34b | >100 | 0.687 | 60 | 0g |

| 34c | 1.476 | 0.560 | 40 | 0g | |

| 34d | >100 | >100 | -f | -f | |

| 34e | >100 | N/Af | -f | -f | |

| 34f | >100 | -g | -f | -f | |

| 34g | >100 | 2.594 | -f | -f | |

| 34h | >100 | >100 | -f | -f | |

| 1 [R-Bicalutamide] | 0.509 | 0.248 | 0g | 0g | |

| 2 [Enzalutamide] | 3.641 | 0.216 | 0g | 0g | |

| 4 [Darolutamide] | 4.231 | 0.048 | -f | -f | |

| 6 [Enobosarm]c | 0.0038 | 0.0038c | Agonistd | Agonistd | |

Class I and II derivatives were in which the B-ring was substituted quinoline, carbazole, or benzotriazole were found to be selective androgen receptor degraders (SARDs).

AR binding, transactivation, and degradation assays were performed.

In vitro transcriptional activation was run in agonist mode for which the EC50 value was previously reported.13

The full agonist Enobosarm (compound 6) increases AR protein expression.

In vitro transcriptional activation was run in antagonist mode for which the IC50 value was previously reported.13 Tested at 10 μM concentration.

Not available (N/A).

No effect.

Table 5.

In Vitro Pharmacological Activity of Class II and III B-Ring Derivatives (Compounds 31a–s, 32a–f, and 35a–k)a

| Class | Binding (Ki) Transactivation (IC50) (μM) | SARD Activity (% degradation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| (ID) | Ki (DHT=1nM)b | IC50b IC50 | Full Lengthb (LNCaP) @1 μM | Splice Variantb (22RV1) @10 μM | |

| 8 | 0.267 | 0.085 | 76 | 87 | |

| 31a | 0.724 | 0.999 | 7, 68c | -d | |

| 31b | 1.399 | 0.721 | 51 | 0 | |

| 31c | 0.883 | 1.662 | 0 | 75 | |

| 31d | 0.913 | 0.371 | 0 | 0 | |

| 31e | 1.589 | 1.024 | 0 | 78 | |

| 31f | 0.493 | >100 | 50 | 0 | |

| 31g | 0.474 | 3.616 | 64 | 0 | |

| 31h | 0.318 | 0.274 | 72 | 84 | |

| 31i | 0.755 | 0.367 | 60 | 80 | |

| 31j | 0.757 | 0.021 | 57, 97c | -d | |

| Class II | 31m | >100 | 0.746 | 0, 83c | -d |

| 31n | >100 | 0.583 | 78 | 56 | |

| 31o | >100 | 0.134 | 44, −2c | 15 | |

| 31p | >100 | 3.434 | -d | -d | |

| 31q | >100 | 0.160 | 66, 90c | 45 | |

| 31r | 0.644 | 0.488 | 112, −69c | 25 | |

| 31s | 0.424 | 0.063 | -d | -d | |

| 32a | 0.137 | 0.173 | 92 | 34 | |

| 32b | 0.172 | >100 | 0 | 0 | |

| 32c | 1.006 | 0.373 | 84 | 100 | |

| 32d | 12.325 | 0.209 | 0 | 0 | |

| 35a | 0.605 | 0.102 | 37, 81c | 53 | |

| 35b | >100 | 0.0267 | 66, 78c | -d | |

| 35c | 1.343 | 0.165 | 34, 46c | -d | |

| 35d | 3.006 | 0.183 | 36, 36c | -d | |

| Class III | 35e | 26.302 | 0.162 | −15, 6.3c | -d |

| 35f | 3.268 | 0.237 | 21, 101c | -d | |

| 35g | >100 | 0.0891 | 22, 37c | -d | |

| 35h | >100 | 0.0485 | 11, 20c | -d | |

| 35i | >100 | 0.02097 | −4 | -d | |

| 35j | 0.796 | 0.1156 | 37 | -d | |

| 35k | >100 | 0.796 | 20, 22c | -d | |

Class II and III derivatives with B-ring 3-position substituted indole, benzimidazole or indazole groups are selective androgen receptor degraders (SARDs).

AR binding, transactivation, and degradation assays were performed, and values were reported in Table 1.

Assessed at 10 μM concentration.

N/A, not available.

We next tested the effects of modifying the indole B-ring 2- or 3-positions (2N- or 3N-) in the Class II-blocked compounds 31a–s and 32a–d or both the 2- and 3-positions (2N- and 3N-) in the Class III-blocked compounds 35a–l in the in vitro assays for binding affinity to the AR LBD (Ki), antagonism of the wildtype (wtAR), and ability to degrade FL and SV AR (% degradation), as shown in Table 5. Of the Class II derivatives with benzimidazoles at the 3-position, compounds 31h–i (3-F and 3-Cl benzimidazoles, respectively) exhibited strong AR binding affinity (Ki = 0.318 μM for compound 31h and 0.755 μM for compound 31i) and reasonable transactivation of AR (IC50 = 0.274 and 0.367 μM, respectively).

The regiospecific isomers 31f and 31g (3N-substitutents, Table 3) exhibited similar binding affinity for AR and similar levels of degradation of FL AR (50% and 64%, respectively), but neither degraded the AR SV mutant (Table 5). While compound 31g retained the weak antagonistic activity for AR transactivation (IC50 = 3.616 μM) like that observed for the 1N-substitutents, compound 31f exhibited no ability to inhibit this activity (IC50 > 100 μM; Table 5). Compound 31j (pyrido A-ring in compound 8) exhibited very robust transactivation of AR- transactivation (IC50 = 0.021 μM; Table 5), which is four times more active than compound 8 (0.085 μM) and ten times more active than compound 2 (0.216 μM). However, compound 31j bound to AR less well (Ki = 0.757 μM) than UT-155 (compound 8; Ki = 0.267 μM) but better than enzalutamide (compound 2; Ki = 3.641 μM), as shown in Table 5. Compounds 31m-q with bulky groups at the 3-position exhibited low binding affinities for AR but strong inhibition of AR transactivation (IC50 = 0.746–0.134 μM) by all of these compounds except for compound 31p (IC50 = 3.434 μM), as shown in Table 5. Interestingly, the presence of a nitro or cyano group on the 3N-indole in compounds 31r and 31s maintained or improved AR binding (Ki) and suppression of AR transactivation activity (IC50) but did not improve stability (data not shown) compared with compound 8.

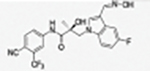

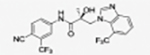

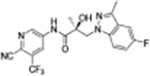

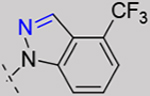

When the 1N- or 2N-indazole compounds 32a–b and 32c–d (structures in Table 3), respectively (Table 5) were assessed for AR binding, antagonistic activity, and degradation (data not shown), the 1N-indazole compounds 32a and 32c were both able to degrade full length AR (92% and 84%, respectively, compared to compound 8, 65–83%) but compound 32c was better able to degrade the AR SV than compound 32a or compound 8 (32a, 34%; 32c, 100%; 8, 60–100%). While compound 32a exhibited weak antagonism of AR transactivation (IC50 = 0.173 μM) and bound to AR better than control compound 8 (Ki = 0.267 μM), compound 32c exhibited poor AR transactivation inhibition (IC50 = 0.373 μM) and AR binding (Ki = 1.006 μM), as shown in Table 5. In contrast, neither of the 2N-indazole compounds 32b and 32d were able to degrade AR FL or SV (0%).

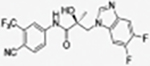

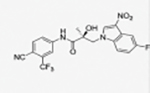

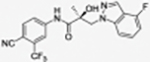

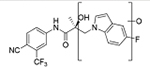

For the Class III, 3-substituted indazoles (compounds 35a-k), compounds with an electron donating group in position 3 (e.g., −CH3, compound 35g) exhibited extraordinarily strong antagonism for AR transactivation (IC50 = 0.0891 μM vs 0.085 μM for compound 8), as shown in Table 5. Other compounds with electron withdrawing groups (e.g., F, Cl, Br, and CF3 in compounds 35a-f) exhibited stronger AR binding (0.102 μM for compound 35a) and low-to-moderate degradation of FL AR (37% for compound 35a), as shown in Table 5. The derivatives with nitrogen A-ring moieties (35b, 35d–e, 35g, and 35i) generally exhibited strong AR antagonist activities (i.e., IC50 = 0.021 μM for 35i) but did not bind robustly to AR LBD (Ki > 100 μM for 35i) and also exhibit weak degradation properties (0% for FL, SV for 35i) as shown in Table 5. Additionally, inhibition of AR transactivation by the class III 3-substitutes indazoles (compounds 35b, 35h, and 35i; IC50 = 0.0267, 0.0485, and 0.02097 μM, respectively) was superior to that by either enzalutamide (compound 2) or UT-155 (compound 8), as shown in Table 5, illustrating that our SAR-derived strategy of blocking the 2- and 3-positions of the indole B-ring was effective.

For easy-going expediency, to summarize antagonism of AR transactivation (IC50) by representative compounds (e.g., 27, 34, 31, 32, and 35) was comparative with that of enzalutamide (compound 2) and the indole UT-155 (compound 8) in Figure S3.

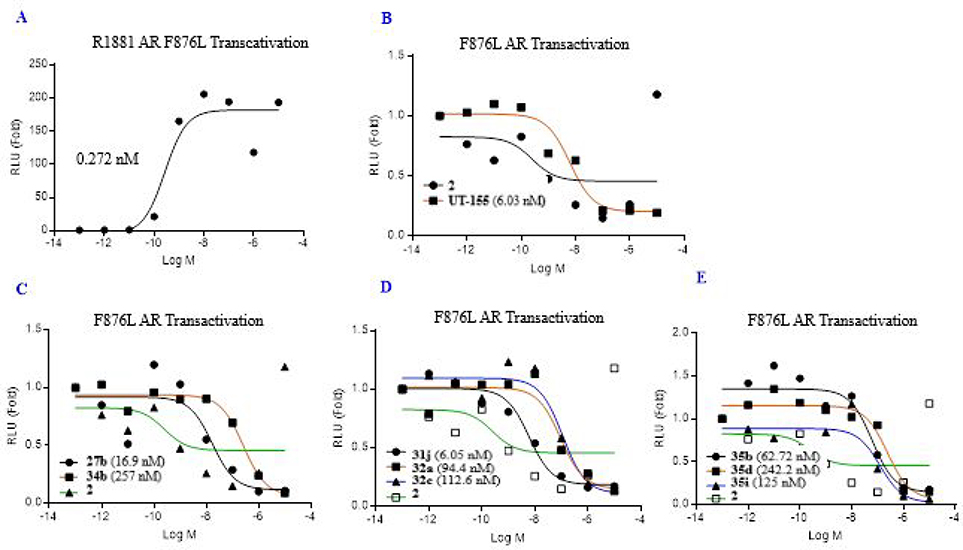

In due course of following our previous report,13 AR antagonism (IC50) evaluated on enzalutamide-resistant mutant AR-F876L (phenylalanine 876 mutated to leucine) and the Enz-Res transactivation IC50 of selected compounds of Class I–III is summarized by classes in Figure 6. In summary, the enzalutamide-resistant mutant AR-F876L (IC50) in Figure 5 as representative compounds (e.g., 27, 34, 31, 32 and 35) generally demonstrated to be compatible with their AR wild-type (wtAR) shown in Figure 5 and Figure S3.

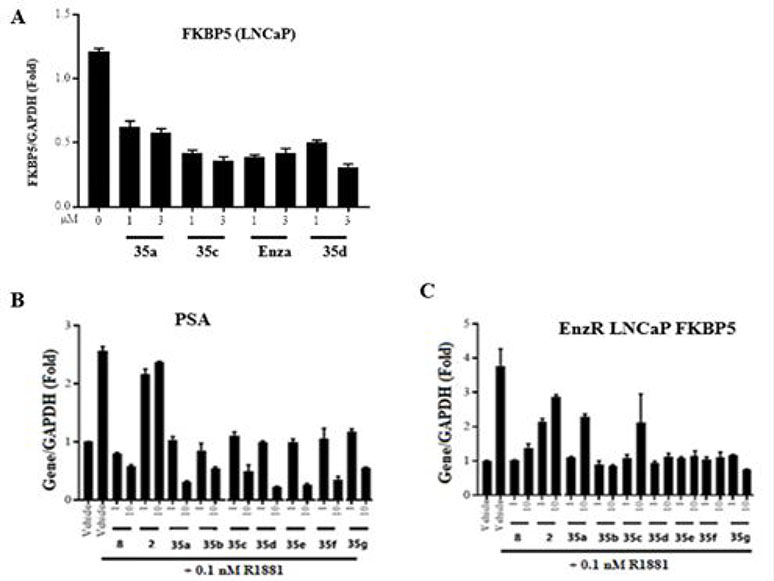

Figure 6.

Effect of 35-series compounds on transcription of AR-regulated gene FKBP5 and PSA in prostate cancer LNCaP cells, and FKBP5 in enzalutamide-resistant LNCaP cells. (A-B) LNCaP cells or (C) enzalutamide-resistant LNCaP cells were plated and maintained in RPMI+1%FBS medium for 2 days prior to treatment with AR agonist R1881 (0.1 nM) and the drug indicated in the figure as antagonist (1, 3, or 10 μM). After 24h, total RNA was isolated, analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) with the indicated primers and probes. Signals were normalized to those of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Detection of mRNA encoding (A) AR target gene FKBP5, (B) prostate-specific antigen (PSA), or (C) FKBP5 in enzalutamide-resistant LNCaP cells. Levels of each mRNA were compared to those after treatment with enzalutamide (compound 2) or (B–C) enzalutamide (compound 2) and UT-155 (compound 8). These compounds antagonized the function of AR in both LNCaP cells and LNCaP cell derivatives that are enzalutamide resistant.

Figure 5.

Class I~III antagonism of F876L mutant AR transactivation. (A) R1881. (B) Enzalutamide (2) and UT-155 (8). (C) Class I: carbazole and benzotriazole in B-ring). (D) Class II (benzimidazole and indazole in B-ring). (E) Class III (3-substituted indazoles in B-ring): AR with F876L (phenylalanine 876 mutated to leucine), GRE-LUC, and CMV-renilla LUC transfected in COS cells. Cells treated 24 h after transfection with 0.1 nM R1881 (agonist) and a dose response of antagonists. Luciferase assay performed 48 h after transfection. The effect of each compound conducted in antagonistic mode (in the presence of 0.1 nM R1881). IC50 values of the Class I~III calculated and provided in the figure.

We next examined the ability of selected 3-substituted indazoles in the compound 35 series to inhibit transcription of enzalutamide-resistant AR-F876L (phenylalanine 876 mutated to leucine) in cultured LNCaP cells (Figure 6), as described in the legend to Figure 6 and the Experimental section in chapter 7–14 in Supporting Information section. The results indicated that treatment of LNCaP androgen-sensitive human prostate cancer cells with increasing concentrations (1 to 3 μM) of enzalutamide (Enzalutamide, compound 2) or 3-substituted indazole compounds 35a, 35c, and 35d reduced expression of the mRNA encoding AR-target gene FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5), as shown in Figure 6.

We also evaluated levels of the mRNA that encodes prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in LNCaP cells treated with series 35 compounds. The position 2- and 3-blocked compounds 35a, 35c and 35d exhibited a dose-dependent reduction in PSA (1 to 10 μM), as shown in Figure 6B. Finally, we examined the effect of these compounds on FKBP5 expression in LNCaP cell derivatives that are resistant to enzalutamide (EnzR). While enzalutamide (compound 2) treatment was ineffective in these cells as expected, both parental indole UT-155 (compound 8) and the 35 series compounds were effective in decreasing levels of FKBP5 mRNA despite the enzalutamide resistance (Figure 6C). In summary, most of compound 35 series showed inhibition of FKBP5 and PSA mRNAs in both LNCaP and enzalutamide resistance LNCaP cells.

2.4. In Vitro Metabolic Stabilities of Class I, II, and III Derivatives in Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLM).

We measured the stability of selected class I–III derivatives using a metabolic assay in mouse liver microsomes (MLM) supplemented with the cofactors of enzymes involved in phase I and II metabolism. The half-life (T1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint) values shown in Table 6 were calculated as a predictor of the distribution, metabolism, and pharmacokinetic (PK) properties of these compounds.

Table 6.

In Vitro Metabolic Stability Of Class I, II, and III in Mouse Liver Microsomes (MLM)

| DMPK (MLM)a |

DMPK (MLM)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | T1/2 (min) | CLint (mL/min/mg) | ID | T1/2 (min) | CLint (mL/min/mg) | ||

| Class I | 27b | 41.77 | 1.66 | 35b | 45.00 | 1.5 | |

| 27c | 39.94 | 1.735 | 35c | 23.66 | 2.93 | ||

| 31h | 7.70 | 8.90 | Class III | 35d | 49.46 | 1.4 | |

| 31i | 23.44 | 2.96 | 35g | 22.60 | 3.1 | ||

| 31j | 14.60 | 4.70 | 35h | 105.00 | 0.66 | ||

| 31l | 55.00 | 1.30 | 35i | 120.60 | 0.60 | ||

| Class II | 31o | 50.15 | 1.40 | ||||

| 31q | 12.63 | 5.5 | |||||

| 32a | 13.29 | 5.2 | 8 22 | Antagonist | 12.35 | 5.614 | |

| 32c | 53.71 | 1.29 | 1 | Antagonist | 10.04b | 86.316 | |

| 32d | 35.46 | 1.96 | 6 | Agonist | 360.00 | 1.416 | |

Compounds were incubated with MLM and cofactors for phases I and II, as described in the Experimental Section.

The half-lives of most of the Class I–III derivatives were longer than that of parental indole UT-155 (compound 8; T1/2 = 12.35 min). For example, the B-ring Class I derivatives with bulky carbazole groups (compounds 27b and 27c) exhibited T1/2 values of 41.77 and 39.94 min, respectively. The Class II derivatives with F-, Cl- or CN- in the 3-position of the indole B-ring (compounds 31h, 31i, and 31q) exhibited relatively unfavorable in vitro metabolic stabilities with T1/2 values of 7.70, 23.44, and 12.63 min, respectively, and CLint values of 8.9, 2.96, and 5.5 mL/min/mg, respectively, relative to 5.614 mL/min/mg for UT-155 (compound 8), as shown in Table 6). Compound 31j with a pyrido A-ring exhibited a marginal increase in T1/2 to 14.60 min relative to that of compound 8, suggesting that while the pyrido group protected the A-ring from metabolism, it was primarily its B-ring that was metabolized. Compounds 31l, 31n, and 31o, all of which have a 3-carbaldehyde or oxime B-ring, exhibited significantly increased half-lives (T1/2 = 55.0, 36.32, and 50.15 min, respectively), suggesting that the 3-position of the indole in B-ring is critical for in vitro metabolic stability.

The 4-F substituted B-ring indazole of compound 32a (T1/2 = 13.29 min) manifested more stable elements than the parental indole UT-155 (compound 8), although the half-lives of the two compounds were roughly comparable, whereas the CF3 group on the indazole in compound 32c dramatically decreased its metabolism (T1/2 = 53.71 min) and resulted in slower clearance from plasma (CLint = 1.29 mL/min/mg). The B-ring indazole regioisomer, compound 32d, also increased its stability (T1/2 = 35.46 min).

Finally, the 3-indazole substituted 35 series compounds, particularly the indazole dihalides in positions 3 and 4 or 3 and 5 of compounds 35b–c and 35g, exhibited a longer half-life in MLM. For example, the 3-methyl-5-fluoro indazole compound 35g was more stable (T1/2 = 23.66 min) than UT-155 (compound 8; T1/2 = 12.35 min). Compounds 35h and 35i with electron withdrawing groups in this position exhibited even greater stability, with T1/2 values of 105 min for 35h and 120.60 min for 35i. The 3-substituted indazole compound 35i also exhibited improved potency in inhibiting AR transactivation (IC50 = 0.021 μM), relative to UT-155 (compound 8; IC50 = 0.085 μM) or enzalutamide (compound 2; IC50 = 0.216 μM). In summary, AR binding and AR antagonistic activity of UT-155 derivatives with Class I–III B-ring substituents appear to be optimized relative to the parental indole compound 8 (Tables 4 and 5).

2.5. In Vivo Antagonism of Compounds 31 and 35 in Rats.21,22

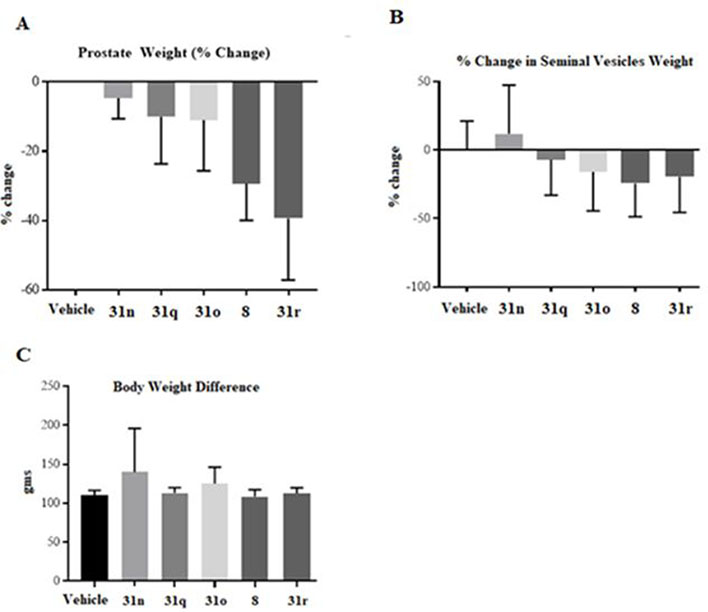

To examine the SAR of position 2- and 3-substituted indole B-rings in the in vivo test, compounds in the 31 and 35 series were selected for analysis by in vivo Hershberger assay in rats (Figures 7 and 8). We selected the 31 series compounds based on their metabolic stability.

Figure 7.

In vivo antagonism of AR by UT-155 (compound 8) and series 31 compounds. Growth of androgen-dependent organs in rats using an in vivoHershberger assay.21–24 Rats were treated orally (n = 5/group) for 14 d with 40 mg/kg/day of a vehicle, either indicated 31 series compounds or compound 8. Animals were sacrificed, and weights of prostate (A) and seminal vesicles (B) were measured and normalized to body weight. (C) Body Weight Difference.

Figure 8.

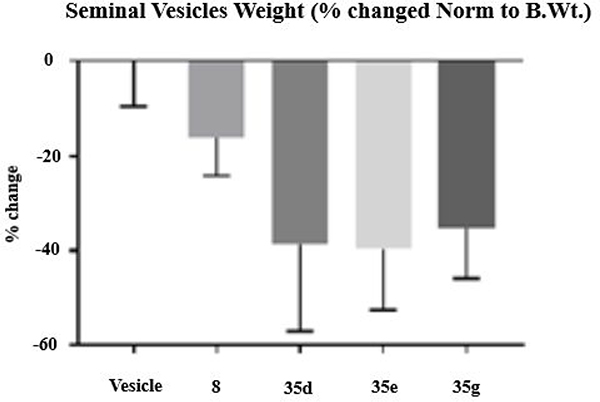

In vivo antagonism of 35 series compounds. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (100–120 g) were treated orally with either vehicle or 20 mg/kg of compounds 8, 35d, 35e, or 35g for 13 days. Animals were sacrificed on the 14th day, and seminal vesicle weights were recorded. The inhibition of androgen-dependent seminal vesicle growth, measured as loss of organ weight by 8, 35d, 35e, and 35g vs vehicle, was statistically significant (p = 0.0031). N = 5/group.

2.5.1. Hershberger Assays in Rats with 31 Series.

For the evaluation of in vivo antagonistic efficacy, intact male Sprague–Dawley rats (6–8 weeks old) were randomized into groups based on body weight and treated orally with a vehicle, 40 mg/kg/day of UT-155 (compound 8) or 40 mg/kg/day of the indicated compound 31 derivative for 14 days.

The animals were sacrificed, their prostates and seminal vesicles were weighed, and the organ weights were normalized to body weight for each animal. The tested compounds were 31o (pyrido A-ring and 3-oxime B-ring); 31r (pyrido A-ring and 3-CN B-ring); 31n (nonpyrido A-ring and 3-oxime B-ring); and 31q (nonpyrido A-ring and 3-CN B-ring), as shown in Figure 7. Treatment of rats with molecules containing an oxime moiety in the B-ring (compounds 31o and 31n) exhibited relatively poor in vivo activity (less than 20% atrophy of prostate and seminal vesicles), relative to compound 8 (nearly 30%), as shown in Figure 7A. Despite both having cyano-substituted B-rings, treatment with compound 31r led to greater atrophy of the prostate (weight ~4 times less than that of 31o (Figure 7A)) but comparable effects as 31o on the seminal vesicles (Figure 7B), while the effect of treatment with 31q on size of the prostate and seminal vesicles were comparable with that of 31n (Figure 7A).

2.5.2. In Vivo Antagonism of Selected 35 Series Compounds in Rats.

To further evaluate the in vivo SAR of the 3-pyrido A-ring compounds 35d (3Cl, 5F-indazole in B-ring), 35e (3Br, 5F-indazole), and 35g (3CH3, 5F-indazole), we performed a Hershberger assay on intact male rats with either vehicle alone or UT-155 indole (compound 8) as controls (Figure 8). While treatment with the indole (compound 8) led to a change in the weight of the seminal vesicles of less than 20%, relative to the vehicle, 3-protected indazole compounds 35d, 35e, and 35g caused a nearly 40% increase in atrophy of the rat AR-dependent seminal vesicles (Figure 8). In summary, the 3-substituted indazoles (35d, 35e, and 35g) exhibited robust AR antagonism in vivo in rats using a Hershberger assay.

2.6. Metabolic Study of Indole UT-155 (Compound 8) and Its Indazole Derivative (Compound 32c).

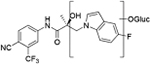

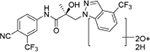

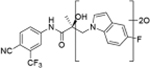

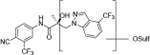

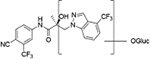

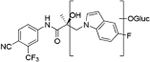

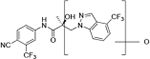

Compounds 32c (indazole) and 8 (indole) were selected for exploration of the metabolic stability of the indole template, especially the 2- and 3-positions of indole UT-155 (compound 8), by systematically eliminating metabolic soft spots in the indole nucleus. Thus, we examined the stability of indole 8 and the 2N-protected indazole 32c in the hepatocytes (liver cells) of several species, including mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human, to enable lead compound selection. We detected nine metabolites (M1–M9) of indole compound 8 that displayed oxidation and/or glycosylation (Table 7). By comparison, the protected mode of indazole 32c resulted in detection of fewer metabolites (M1–M5), suggesting that it was more stable than indole 8 (Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of Deprotonated Molecular Ions for Compounds 8 and 32c and Identified Metabolites

| Panel A |

Compound 8 |

|

Panel B |

Compound 32c |

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Designation | Retention time (min) | [M – H]− | Proposed Metabolite Identification | Metabolite Designation | Retention time (min) | [M – H]− | Proposed Metabolite Identification | |

| M1 | 17.73a | 420 |

|

M1(3) | 18.20a | 489 |

|

|

| M2 | 17.79a | 596 |

|

M2 | 18.37a | 489 |

|

|

| M3 | 17.97b | 436 |

|

M3(2) | 18.68a | 551 |

|

|

| M4(2) | 18.13a | 436 |

|

|

M4(1) | 19.17a | 647 |

|

| M5(3) | 18.29a | 596 |

|

M5 | 20.25a | 471 |

|

|

| M6 | 18.99a | 500 |

|

32c | 20.88a | 455 |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| M7 | 19.10a | 420 |

|

|||||

| M8(1) | 19.62a | 580 |

|

|||||

| M9 | 19.64a | 420 |

|

|||||

| UT-155 (8) | 20.52a | 404 |

|

|||||

|

|

||||||||

Retention time from analysis of human AR.

Retention time from analysis of mouse AR.

Biological Experiments are described in Supplemental Section 3–11. This study was conducted by Covance Laboratories Inc., 3301 Kinsman Boulevard, Madison, WI, in accordance with the protocol and Covance standard operating procedures (SOPs).

2.6.1. Provisional Biotransformation Pathways of UT-155 (Compound 8).

We detected evidence for four major metabolic pathways in the degradation of compound 8 (Table 7, panel A), as follows. We detected 1) oxidation in metabolites M1, M3, M4, M7, and M9; 2) O-glucuronidation in metabolites M2 and M5; 3) O-sulfation in metabolite M6; and 4) direct glucuronidation in metabolite M8. The putative structures of these metabolites and their relative abundance in each species by peak area are shown in Table 7, panel A. The most abundant metabolite in human liver cells (M8) was also observed in monkey hepatocytes but not in those of rat, dog, or mouse. The other major metabolites detected in human hepatocytes (M4, M5) were also detected in all other species assessed.

M1 and M6 were the major metabolites in rat hepatocytes; M2 in rat, dog, and mouse; M7 in dog and mouse; and M9 in monkey; all of these metabolites also observed at varying abundance in human hepatocytes. M3 was a major metabolite in mouse hepatocytes but was not detected in human hepatocytes.

2.6.2. Provisional Biotransformation Pathways of 32c.

We also detected evidence for four major metabolic pathways in the degradation of compound 32c (Table 7, panel B), as follows. We detected 1) dihydro-diols in M1 and M2; 2) O-sulfation in M3; 3) O-glucuronidation in M4; and 4) oxidation in M5. The putative structures of these metabolites are shown in Table 7, panel B, and their relative abundance in each species by peak area is shown in Table 9. The three most abundant metabolites in human hepatocytes (M4, M3, and M1) were observed in all other species evaluated. M2 was a major metabolite in monkey hepatocytes and M5 in dog hepatocytes, both of which were observed in human hepatocytes.

Table 9.

Relative Abundance of Identified Metabolites for Compound 32c in Each Species

| Peak areas (× 103) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M #a | [M – H] − | Mass Shift | Human | Rat | Dog | Monkey | Mouse |

| M1 | 489.1054 | 34.9955 | 286***c | 74.8***c | 20.7***c | 111 | 49.8 |

| M2 | 489.1054 | 34.9955 | 254 | NAb | NA | 150***c | NA |

| M3 | 551.0460 | 192.0270 | 1122**c | 583**c | 36.0**c | 839**c | 52.7***c |

| M4 | 647.1287 | 192.0270 | 6147*c | 3460*c | 208*c | 7131*c | 1206*c |

| M5 | 471.0892 | 15.9949 | 28.5 | NA | 19.4 | NA | 1170**c |

M #, Metabolite number.

NA, not assessed.

*, Most abundant metabolite in species; **, second most abundant; and ***, third most abundant.

3. CONCLUSIONS AND DISCUSSION

In our continued effort to discover bioactive small molecules that antagonize the AR activity for treatment of advanced PC, we designed and evaluated more than 50 new compounds with alteration of the 2- and/or 3-positions in the indole B-ring of compound UT-155 (compound 8) that can be divided into three structural classes. The obtained results are summarized in Table 10.

Table 10.

Summary of the SAR Study to Compare the Pharmaceutical Properties of Indole UT-155 (Compound 8) Substituted with Class I—III Blocking Groups at the 2- and/or 3-Positions of the B-Ring

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | X | Y | AR LBD Binding (Ki) | DMPK (half-life; T1/2) | EnzR antiandrogenic effect (IC50) | ||

| Class I | 27 | CH | carbazole | ↓ | ↑↑ | Equal or less | |

| 34 | CH | N | N | ↓ | ↑↑ | Equal or less | |

| Class II | 31 | CH or N | CH | N- or C-substituted | Equal or less | ↑ | Equal or less |

| 32 | CH | N | CH | Equal or less | ↑↑ | ↑ | |

| Class III | 35 | CH or N | N | C-substituted | Equal or less | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ |

The Class II derivative, compound 32c, that contained an indazole at position 2 of the indole B-ring exhibited a dramatic improvement in in vitro metabolic stability (T1/2 = 53.71 min), which is four times more stable than the parental indole compound 8, as shown in Table 6. This result suggested that the 2- and 3-positions of the parental indole B-ring in compound 8 were the most metabolically labile. This was also supported by the results of the metabolic assessment of compound 32c, which showed that there was comparatively little metabolism of the protected 2- and 3-positions of compound 32c and no glycosylation on the B-ring hydroxyl group (Table 7, panel B and Table 9).

By comparison, metabolic assessment of parental indole compound 8 suggested that the 2- and 3-positions of the B-ring were metabolized by oxidation/glycosylation and sulfonylation/glycosylation on the hydroxyl of compound 8 to yield the major metabolites M1–M9 (Table 7, panel A and Table 8). We further showed that the presence of a pyrido group on the indole A ring, for example in compound 20, strengthened the antagonistic effect for enzalutamide-resistant AR relative to that of the parental indole compound 8 (IC50 = 0.027 μM for compound 20; 0.085 μM for compound 8), although the two compounds exhibited similar stability (half-life) and similar binding affinity (Ki) for the AR ligand binding domain (LBD), as shown in Table 1.

Table 8.

Relative Abundance of Identified Metabolites for UT-155 (Compound 8) in Each Species

| Peak areas (× 103) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M #a | [M – H] − | Mass Shift | Human | Rat | Dog | Monkey | Mouse |

| M1 | 420.0971 | 15.9949 | 169 | 152***c | NAb | NAb | NAb |

| M2 | 596.1282 | 192.0270 | 569 | 267**c | 225**c | NAb | 111**c |

| M3 | 436.0920 | 31.9898 | 0.00 | NAb | NAb | NAb | 30.4***c |

| M4 | 436.0920 | 31.9898 | 1108**c | 18.6 | 67.3***c | 142**c | 8.15 |

| M5 | 596.1292 | 192.0270 | 729***c | 46.0 | 8.20 | 185*c | 12.3 |

| M6 | 500.0539 | 95.9517 | 283 | 333*c | NAb | NAb | NAb |

| M7 | 420.0971 | 15.9949 | 603 | NAb | 479*c | NAb | 129*c |

| M8 | 580.1343 | 176.0321 | 1913*c | 0.00 | 0.00 | 13.9 | 0.00 |

| M9 | 420.0971 | 15.9949 | 38.5 | NAb | NAb | 23.7***c | NAb |

M #, Metabolite number.

NA, not assessed.

*, Most abundant metabolite in species; **, second most abundant; and ***, third most abundant.

When we combined the A-ring pyrido moiety (in compound 20) with the 3-sustituted indazole B-ring (in compound 32c), we discovered that the resulting compound 35i exhibited four times the potency in antagonizing AR transactivation (IC50 = 0.021 μM, as shown in Table 5) and ten times greater metabolic stability (T1/2 = 120.6 min, as shown in Table 7) than the parental indole compound 8, and this activity was enzalutamide resistant. Compounds in the 31, 32, and 35 series exhibited improved antagonism of AR transactivation (IC50) and greater stability than compound 8 and were also able to degrade both FL and SV versions of AR (Tables 4 and 5). To determine the selectivity of this scaffold we performed a proteomics analysis with UT-155 in AR-negative PC-3 cells. UT-155 did not alter the proteome, suggesting that the scaffold selectively modulates AR and androgenic pathways and does not have off-target effects.

In summary, the current study explored the strategy of blocking the 2- and 3-positions of the B-ring indole of UT-155 (compound 8) in hopes of improving its stability. The success of this strategy was highlighted by our findings that many of the resulting compounds demonstrated not only increased stability but also strengthened in vitro (e.g., antagonism, SARD, and antiproliferative assays)/in vivo (e.g., xenografts) activities as AR antagonists that retained their functionalities even against enzalutamide-resistant forms of AR. Collectively, this metabolism-guided study could be a stepping stone to the discovery of potent AR antagonist-targeted small molecules.

4. EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

4.1. General Chemistry Methods.

All solvents and chemicals used for synthesis were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (Burlington, MA), Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA), Matrix Scientific (Columbia, SC), Ambeed Inc. (Arlington Heights, IL), AURUM Pharmatech (Franklin Park, NJ), Combi-Blocks Inc. (San Diego, CA), and others and were used without further purification. All moisture-sensitive reactions were performed under an argon atmosphere. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on precoated silica gel plates (Merck Kieselgel 60 F254 layer thickness 0.25 mm). NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometer (Billerica, MA). Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) in chloroform (CDCl3), Acetone-d6 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-d6. The structures of synthesized compounds were also assigned using 1H–1H 2D-COSY and 2D-NOESY NMR analytical methods. Flash column chromatography was performed using silica gel (230–400 mesh, Merck) columns. Mass spectral data was collected on a Bruker Esquire liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LCMS) system (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) equipped with an electrospray/ion trap instrument in positive and negative ion modes (ESI Source Solutions, LLC, Woburn, MA). The purity of the final compounds was analyzed by an Agilent 1100 high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Santa Clara, CA). HPLC conditions: 45% acetonitrile at flow rate of 1.0 mL/min using a LUNA 5 μm C18 100A column (250 × 4.60 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) at ambient temperature. UV detection was set at 340 or 245 nm. Purities of the compounds were determined by careful integration of areas for all peaks detected and determined as ≥95% for all compounds evaluated for biological activity against PC.

4.2. Metabolic Study of Compounds 8 and 32c.

This study was conducted by Covance Laboratories Inc. (Covance; Madison, WI), in accordance with the protocol and standard operating procedures (SOPs) from Covance.

Biotransformation in Hepatocytes.

The biotransformation of test articles was assessed by incubation of mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human hepatocytes with 10 μM solutions of compounds 8 or 32c for 0 and 120 min. The three major metabolites in the 120 min samples were identified for each species. The major metabolites for the human cells were assessed in all preclinical species tested, while the major metabolites for each preclinical species were assessed in human hepatocytes, but not in hepatocytes from other species. Due to saturation of the parent LCMS signal, the quantitation of the metabolites as a percentage of the parent compound was not possible and was instead limited to the metabolite peak area.

Experimental Assessment in Cultured Hepatocytes.

Metabolic biotransformation of the test articles was assessed in vitro using cultured mouse, rat, dog, monkey, and human hepatocytes. Each of nine test articles (10 μM each) were incubated separately with approximately 1 × 106 hepatocytes/mL, suspended in Williams’ Medium E, at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Parallel cultures were terminated after 0 or 120 min by the addition of acetonitrile, and the samples were stored frozen at −20 °C until time of analysis. All incubations were conducted in duplicate. Metabolites of five selected AR antagonists were characterized using quantitative liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Metabolite structures were proposed based on mass accuracy and their ion fragmentation.

4.3. General Synthetic Procedures.

4.3.1. Synthetic Method A13 (for Compounds 27a–27 e, 31a–31b, 31h–31s, 32c–32d, 34a–34 h, and 35a–35g).

Under an argon atmosphere, a 60% dispersion of NaH (228 mg, 5.7 mmol) in mineral oil was added to 30 mL of anhydrous tetrahydrofuran (THF) in a dry two-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a dropping funnel, and the resulting solution was stirred in an ice–water bath for 30 min (Scheme 1). Separately, 2.84 mmol of substituted compound 25 (or compounds 28, 29, 30, 32, or 33) was dissolved in 100 mL THF, and the resulting solution was added to the flask through the dropping funnel under an argon atmosphere and stirred overnight at RT. After adding 1 mL of H2O, the reaction mixture was condensed under reduced pressure, dispersed into 50 mL of ethyl acetate (EtOAc), washed twice with 50 mL H2O, evaporated, dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and evaporated to dryness. The mixture was purified with flash column chromatography as an EtOAc/hexane eluent to produce the desired compounds.

4.3.2. Synthetic Method B (for Compound 31c).

To a dry, nitrogen-purged 50 mL round-bottom flask, R-bromo amide (compound 23, 1 mmol), substituted benzimidazole or indazole (1 mmol), and K2CO3 (415 mg, 3 mmol) were dissolved into 10 mL of DMF. The mixture was heated to 80 °C for 2 h, then cooled to RT. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, poured into 10 mL of H2O, and extracted 3 times with EtOAc. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, concentrated, purified by flash chromatography on a silica gel column, and eluted with EtOAc to produce the desired product.

4.3.3. Synthetic Method C (for Compounds 31d–31g, 32a, and 32b).

Under an argon atmosphere, 1.5 mL of lithium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (1 mmol; 1 M solution in THF) was slowly added to a solution of substituted-benzimidazole (compound 29; 1 mmol in 10 mL THF) at −78 °C and stirred for 30 min. A solution of aryl bromide (compound 23, 1 mmol in 5 mL THF) was added dropwise to the solution. The reaction mixture was stirred at −78 °C for 30 min, then at RT overnight. The reaction was quenched by the addition of 10 mL of a saturated NH4Cl solution. The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and dispersed into excess EtOAc, dried over Na2SO4, concentrated, and purified by flash column chromatography (EtOAc/hexane) to produce the target product.

4.3.4. Synthetic Method D37 (for Compounds 31n–31p).

Hydroxylamine hydrochloride (for compounds 31n or 31o) or acetohydrazide (1.5 mmol for compound 31p) was added to a solution of compound 31l or 31m (0.69 mmol in 5 mL pyridine). The solution was stirred overnight at RT before being evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in 20 mL of EtOAc, and 10 mL of H2O was added to the solution. The residue was filtered and washed with H2O or purified with flash column chromatography and eluted in EtOAc/hexane to produce the desired compounds.

4.4. Synthesis and Analysis of Compounds 26, 27(a–e), 28, 31(a–s), 32(a–d), 34(a–h), and 35(a–k).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(2,3-dioxoindolin-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (26).

To a dry, nitrogen-purged 100 mL round-bottom flask under an argon atmosphere was added a mixture of indoline-2,3-dione (147 mg, 10.0 mmol,), (R)-3-bromo-N-(4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (351 mg, 10.0 mmol), and K2CO3 (14.5 mmol, 277 mg) in 5 mL of DMF and stirred vigorously at RT for 12 h. The reaction mixture was poured into 50 mL of H2O and extracted 3 times with 10 mL of EtOAc, washed with brine (saturated NaCl in H2O), aqueous NH4Cl, and H2O. The EtOAc extract was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, concentrated under reduced pressure, and purified by flash column chromatography using EtOAc/hexane (1:1, v/v) as an eluent to produce compound 26 as a brown gel (yield 34%). UV λmax 197.45, 270.45 nm; HPLC (45% acetonitrile): tR 3.18 min, purity 97.82%; MS (ESI) m/z 416.2 [M – H] −; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.16 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.09 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 6.56 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (bs, OH), 3.84 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 3.25 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 1.57 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3,100 MHz) δ173.9, 158.5, 156.2, 142.7, 141.4, 135.8, 133.9 (q, J = 33 Hz), 123.4, 121.8, 120.7, 117.3 (q, J = 5 Hz), 116.4, 116.3, 116.1, 115.9, 115.5, 104.6, 60.5, 21.1; 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.21.

(S)-3-(9H-Carbazol-9-yl)-N-(4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (27a).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 27a (yield 76%). MS (ESI) 436.1 [M – H] −; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.81 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.09–8.06 (m, 2H), 7.84 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.71 (m, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.45–7.39 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.26 (m, 2H), 4.80 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 4.62 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 2.57 (bs, 1H, OH), 1.69 (s, 3H).

(S)-3-(9H-Carbazol-9-yl)-N-(3-chloro-4-cyanophenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (27b).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 27b (yield 77%). MS (ESI) m/z 402.3 [M – H]−; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.75 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.08 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.56–7.54 (m, 3H), 7.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27–7.25 (m, 2H), 4.78 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (d, J = 15.6 Hz, 1H), 2.65 (bs, 1H, OH), 1.66 (s, 3H).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(3-fluoro-9H-carbazol-9-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (27c).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 27c as a white solid (yield 73.5%). Mass (ESI) 453.9 [M – H] −; (ESI): 478.1[M + Na] +; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.36 (s, 1H, NH), 8.25 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.12–8.09 (m, 2H, ArH), 8.04 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.95 (dd, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.66 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.64 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.37 (dt, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.20 (td, J = 9.2 Hz, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.13 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.34 (s, 1H, OH), 4.70 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.55 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.52 (s, 3H, CH3).

(S)-N-(3-Chloro-4-cyanophenyl)-3-(3-fluoro-9H-carbazol-9-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (27d).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 27d as a white solid/needles (yield 98%). Mass (ESI) 420.1 [M – H] −; (ESI): 444.1 [M + Na] +;1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ10.20 (s, 1H, NH), 8.12(d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.05 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.96 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.86 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.80 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.69–7.66 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.41 (t, J = 8.0, 1H, ArH), 7.24 (dt, J = 9.6, 2.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.16 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 6.34 (s, 1H, OH), 4.70 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.54 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.52 (s, 3H, CH3).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(3,6-difluoro-9H-carbazol-9-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (27e).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 27e as a white solid (yield 85.8%). Mass (ESI) 471.9 [M – H] −; 496.1 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.33 (s, 1H, NH), 8.22 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.11 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.05 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.98 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.96 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.68–7.65 (m, 2H, ArH), 7.27–7.22 (m, 2H, ArH), 6.36 (s, 1H, OH), 4.72 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.54 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.53 (s, 3H, CH3).

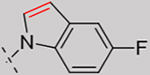

3,5-Difluoro-1H-indole (28).

Selectfluor (872 mg, 2.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv) as a fluorine donor, Li2CO3 (296 mg, 4.0 mmol, 4.0 equiv), dichloromethane (3.3 mL), and H2O (1.7 mL) were added to a 50 mL round-bottom flask containing a magnetic stir bar. Carboxylic acid (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h in an ice bath. The reaction mixture was diluted with 40 mL of H2O and extracted twice with 20 mL of dichloromethane (DCM). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (n-hexane:DCM = 2:1) to produce compound 28 as a dark brown oil (yield 68%). MS (ESI) m/z 154.83[M + H] +; 152.03 [M – H] −; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 7.86 (bs, 1H, NH), 7.25 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.20–7.16 (m, 1H), 6.97 (t, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), ;19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −123.99 (d, JF–F = 2.8 Hz), −174.74 (d, JF–F = 4.0 Hz).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(5,6-difluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31a).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31a as a white solid (yield 12.6%). Mass (ESI) 422.7 [M – H] −; 447.0 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.36 (s, 1H, NH), 8.25 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.21 (s, 1H, ArH), 8.14 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.06 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.43–7.40 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.26–7.19 (m, 1H, ArH), 6.51 (s, 1H, OH), 4.65 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.41 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.42 (s, 3H, CH3).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(5,6-difluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31b).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31b as a white solid (yield 28.4%). Mass (ESI) 422.7 [M – H] −; 447.0 [M + Na] +;1 H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.44 (s, 1H, NH), 8.36 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.17 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, ArH), 8.11 (s, 1H, ArH), 8.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.44–7.41 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.21–7.14 (m, 1H, ArH), 6.54 (s, 1H, OH), 4.62 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H, CH), 4.52 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.41 (s, 3H, CH3).

(S)-N-(3-Chloro-4-cyanophenyl)-3-(4-fluoro-1H-benzo[d]-imidazol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31c).

Synthetic Method B was used to produce compound 31c (yield 63%). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C18H15ClF4N4O2: 373.0868. Found: 373.0878 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz) δ 9.77 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.16 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.83 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.18 (m, 1H), 6.99 (dd, J = 11.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.83 (bs, 1H, OH), 4.78 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.69 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.56 (s, 3H).

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(7-fluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31d).

Synthetic Method C was used to produce compound 31d (and compound 31e, see below) as a white solid (total yield of compounds 31d and 31e, 70%; yield of compound 31d, 30%). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H15F4N4O2: 457.1131. Found: 457.1126 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.14 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.08 (s, 1H), 7.96 (s, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (m, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 10.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (bs, 1H, OH), 4.96 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 4.54 (d, J = 13.6 Hz, 1H), 1.54 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.22, −116.56.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(4-fluoro-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31e).

Synthetic Method C was used to produce compound 31e (and compound 31d, see above) as a white solid (total yield of compounds 31d and 31e, 70%; yield of compound 31e, 40%). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H15F4N4O2: 457.1131. Found: 457.1137 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.10 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.79 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.71 (m, 2H), 7.38 (m, 1H), 7.31–7.26 (m, 1H), 6.81 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.01 (bs, 1H, OH), 4.93 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 1.53 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.22, −117.60.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-(4-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl) propanamide (31f).

Synthetic Method C was used to produce compound 31f (and compound 31g, see below) as a light yellowish solid (total yield of compounds 31f and 31g, 66%; yield of compound 31f, 31.9%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (NOESY). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H14F6N4O2: 457.1099 [M + H] +. Found: 457.1090 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.32 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.665 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.92 (bs, 1H, OH), 4.94 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 4.68 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 1.48 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −55.42, −62.14.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-(7-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl) propanamide (31g).

Synthetic Method C was used to produce compound 31g (and compound 31f, see above) as a light yellowish solid (total yield of compounds 31f and 31g, 66%; yield of compound 31g, 34%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (NOESY). HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H14F6N4O2: 457.1099 [M + H] +. Found: 457.1094 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.16 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.07 (s, 1H), 7.95 (bs, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (bs, 1H, OH), 4.70 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.58 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −60.52, −62.29.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(3,5-difluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31h).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31h as a white powder (yield 53%). HPLC (45% acetonitrile): tR 2.77 min, purity 99.06%. UV (λmax) 196.45, 270.45 nm; MS (ESI) m/z 423.20 [M + H] +; 422.02 [M – H] − C20H15F5N3O2 424.1084 [M + H] +; 424.1065 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.80 (bs, 1H, NH), 7.89 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 1H), 7.20 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (t, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (td, J = 9.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 2.57 (s, OH), 1.61 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −62.25, −123.48 (d, JF–F = 3.2 Hz), −173.54 (d, JF–F = 2.8 Hz).

(S)-3-(3-Chloro-5-fluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-N-(4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31i).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31i as a white solid (yield 58%). HPLC (45% acetonitrile): tR 2.89 min, purity 99.06%; UV (λmax) 196.45, 270.45 nm; MS (ESI) m/z C20H15ClF4N3O2: 440.0789 [M + H] +; 440.0797 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.76 (bs, 1H, NH), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.78–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.34 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (s, 1H), 6.97 (td, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.58 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (s, OH), 1.61 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3) δ −62.25, −12.76.

(S)-N-(6-Cyano-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-3-yl)-3-(5-fluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31j).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31j (yield 83%). MS (ESI) m/z 407.20 [M + H] +; 405.02 [M – H] −; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H14F4N4O2: 407.1131 [M + H] +. Found: 407.1128 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.85 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.58 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (s, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 8.8, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 7.19 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (m, 1H), 6.45(d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.64 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 4.33 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 2.93 (bs, 1H, OH), 1.64 (s, 3H). 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.08, −125.26.

(S)-Ethyl 1-(3-((4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl) phenyl) amino)-2-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-oxopropyl)-5-fluoro-1H-indole-3-carboxylate (31k).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31k as a yellowish solid (yield 63%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). MS (ESI) m/z 476.31 [M – H] −; 500.26 [M + Na] +; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H19F4N3O4: 476.1390 [M – H] −. Found: 476.1301 [M – H] −; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.90 (bs, 1H, NH), 7.98 (s, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.77–7.73 (m, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 9.4, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (dd, J = 9.4, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (dt, J = 8.8, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 4.66 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.39 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (s, OH), 1.68 (s, 3H), 1.38 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.26, −120.93.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(5-fluoro-3-formyl-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31l).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31l as a yellowish solid (yield 73%; purity 99.14%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). UV max 195.45, 265.45; MS (ESI) m/z 432.21 [M – H] −, 456.21 [M + Na] +; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H15F4N3O3: 456.0947 [M + Na] +. Found: 456.0887 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ 10.35 (bs, 1H, NH), 9.90 (bs, 1H, CHO), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (dd, J = 9.0, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 9.0, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (dt, J = 9.2, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (s, OH), 4.69 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.47 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ −61.21, −1201.26.

(S)-N-(6-Cyano-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-3-yl)-3-(5-fluoro-3formyl-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31m).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31m as a yellowish solid (yield 73%; purity 99.14%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). MS (ESI) m/z 457.16 [M + Na] +, 433.17 [M – H] −; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H14F4N4O3: 435.3517 [M + H] +. Found: 434.1113 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz) δ 10.08 (bs, 1H, NH), 9.95 (bs, 1H, CHO), 9.14 (s, 1H), 8.69 (s, 1H), 7.80 (dd, J = 9.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (dt, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.85 (s, OH), 4.86 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 1.68 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (Acetone-d6, 400 MHz) δ 114.53, 54.70.

(S,Z)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(5-fluoro-3-((hydroxyimino)methyl)-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31n).

Synthetic Method D37 was used to produce compound 31n as a pink solid (yield 94%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). MS (ESI) m/z 447.21 [M – H] −; 449.24 [M + H] +; 471.23 [M + Na] +; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H16F4N4O4: 449.1237 [M – H] −. Found 449.1235 [M – H] −; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6,400 MHz) δ 11.24 (bs, 1H, NH), 10.34 (bs, 1H, OH), 8.34 (s, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 8.10 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 10.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dt, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (s, OH), 4.60 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 1H), 1.43 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ −61.17, −123.69.

(S)-N-(6-Cyano-5-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-3-yl)-3-(5-fluoro-3-((hydroxyimino)methyl)-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31o).

Synthetic Method D was used to produce compound 31o as a brownish solid (yield 43%; purity 99.33%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). UV max 195.45, 266.45; MS (ESI) m/z 448.19 [M – H] −, 450.22 [M + H] +; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H15F4N5O3: 450.1189 [M + H] +. Found: 450.1192 [M + H] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.73 (bs, 1H, NH), 9.15 (bs, 1H, OH), 8.87 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 8.80 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.28 (m, 2H), 7.02 (dt, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (s, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 10.0, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (dt, J = 8.8, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.46 (s, OH), 4.53 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 1.57 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.18, −121.67.

(S,E)-3-(3-((2-Acetylhydrazono)methyl)-5-fluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-N-(4-cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31p).

Synthetic Method D was used to produce compound 31p as a yellowish solid trans/cis isomer (yield 90.5%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). HPLC (45% acetonitrile): tR 3.22 min, purity = 99.33%. MS (ESI) m/z 488.26 [M – H] −; 490.28 [M + H] +, 512.23 [M + Na] +; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H19F4N5O3: 490.1502 [M + H] +, 512.1322 [M + Na] +. Found: 490.1509 [M + H] +, 512.1328 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 9.50 (s, 0.25·H for cis type), 9.03 (s, 0.75·H, for trans type), 8.97 (s, 0.25·H for cis type), 8.61 (s, 0.75·H, for trans type), 8.16 (bs, 1H, NHC(O)−), 7.83 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.72 (s, 2H, ArH), 7.54 (m, 1H, ArH), 7.52 (s, 1H, ArH), 7.42 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.2 Hz, 1H, ArH), 7.01 (m, 1H, −C=N−NH−), 5.96 (s, 0.25·OH, for cis type), 4.64 (s, 0.75·OH, for trans type), 4.62 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 0.75·H, for trans type), 4.59 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 0.25·H, for cis type), 4.42 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 0.25·H, for cis type), 4.37 (d, J = 14.8 Hz, 0.75H, for trans type), 2.30 (s, 3H), 1.66 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ −62.22, −121.58.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(3-cyano-5-fluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31q).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31q as a brownish solid (yield 63%; purity 98.41%). The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). UV λmax 196.45, 270.45 nm; MS (ESI) m/z 429.12 [M – H] −, 453.19 [M + Na] +; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H14F4N4O2: 431.1131 [M + H] +, 453.0951 [M + Na] +. Found: 431.1112 [M + H] +, 453.1145 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ 10.32 (bs, 1H, NH), 8.20 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8,19 (s, 1H), 8.07 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dt, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (bs, OH), 4.67 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.43 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ −61.23, −121.31.

(S)-N-(6-Cyano-5-(trifluoromethyl) pyridin-3-yl)-3-(3-cyano-5-fluoro-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31r).

Synthetic Method A was used to produce compound 31r as a yellowish solid (yield 37%; purity 98.78%. The structure of the product was determined using 2D NMR (COSY and NOESY). MS (ESI) m/z 430.21 [M – H] −, 432.22 [M + H] +; LCMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H13F4N5O2 432.1084 [M + H] +. Found: 432.1055 [M + H] +; 454.0878 [M + Na] +; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ 10.54 (bs, 1H, NH), 9.14 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.65 (dd, J = 9.2, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 7.33 (dd, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (dt, J = 9.2, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (bs, OH), 4.69 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 4.38 (d, J = 14.4 Hz, 1H), 1.45 (s, 3H); 19F NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ −61.38, −121.27.

(S)-N-(4-Cyano-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-3-(5-fluoro-3-nitro-1H-indol-1-yl)-2-hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide (31s).