Abstract

Background

Establishing care preferences and selecting a prepared medical decision-maker (MDM) are basic components of advance care planning (ACP) and integral to treatment planning. Systematic ACP in the cancer setting is uncommon. We evaluated a systematic social work (SW)-driven process for patient selection of a prepared MDM.

Methods

We used a pre/post design, centered on SW counseling incorporated into standard-of-care practice. New patients with gynecologic malignancies were eligible if they had an available family caregiver or an established Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA). Questionnaires were completed at baseline and 3 months to ascertain MPOA document (MPOAD) completion status (primary objective) and evaluate factors associated with MPOAD completion (secondary objectives).

Results

Three hundred and sixty patient/caregiver dyads consented to participate. One hundred and sixteen (32%) had MPOADs at baseline. Twenty (8%) of the remaining 244 dyads completed MPOADs by 3 months. Two hundred and thirty-six patients completed the values and goals survey at both baseline and follow-up: at follow-up, care preferences were stable in 127 patients (54%), changed toward more aggressive care in 60 (25%), and toward the focus on the quality of life in 49 (21%). Correlation between the patient’s values and goals and their caregiver’s/MPOA’s perception was very weak at baseline, improving to moderate at follow-up. Patients with MPOADs by study completion had statistically significant higher ACP Engagement scores than those without.

Conclusion

A systematic SW-driven intervention did not engage new patients with gynecologic cancers to select and prepare MDMs. Change in care preferences was common, with caregivers’ knowledge of patients’ treatment preferences moderate at best.

Keywords: advance care planning, advance directives, goal-concordant care, medical power of attorney, surrogate medical decision-maker

Advance care planning is valued for promoting patient autonomy at the end-of-life, with the aim of supporting goal-concordant care. This article evaluates a systematic social work-driven process for patient selection of a prepared medical decision-maker, a basic component of advance care planning.

Implications for Practice.

New patients with gynecologic cancers did not engage in a systematic process to select and prepare a surrogate medical decision-maker (MDM), such as a Medical Power of Attorney, important when unable to communicate with the medical team. Many patients changed their cancer treatment preferences over a 3-month period. The correlation of caregivers’ perception of patients’ treatment goals with patients’ was moderate at best. To better promote goal-concordant care, new paradigms of advance care planning (ACP) are needed to prepare patients and their surrogate MDMs for more dynamic medical decision-making than that afforded by advance directives and traditional ACP approaches.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is valued for promoting patient autonomy at the end-of-life, to support goal-concordant care. Contingent upon expert communication, ACP involves sharing knowledge related to prognosis, treatment options, and the patient’s values, goals, and care preferences among patients, family members, and clinicians.1 An available, capable Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA) supports early engagement in and is foundational to ACP, as many individuals lose the capacity for medical decision-making toward the end-of-life.2,3 The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of ACP and the need for surrogate decision-makers to support goal-concordant care.

As national priority,4-6 ACP is an important determinant of patient and family satisfaction with care and is linked with improved bereavement, resource utilization, and reimbursement outcomes.7-9 For individuals with serious medical illnesses, establishing care preferences is integral to treatment planning. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends documentation of advance directive (AD) discussions by the 3rd office visit for patients diagnosed with cancer,10 consistent with patients’ preferences for physician ACP discussion in the outpatient setting.11

Despite these findings, uptake of ACP is erratic and uncommon.4,5,10,12-14 Most clinical practices and hospitals do not have a systematic approach to ACP. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with ACP include White race, higher education, single status, age, and higher annual income. Other factors include anticipated death, more advanced cancer diagnoses, functional status, depression, and experience with medical decision-making for self or others. Communication about diagnosis, prognosis, and care options in the cancer setting, pivotal to ACP, is influenced by culture, acculturation, religiosity, and style of decision-making preferences.2,4,15-28

In our institution, a 3-phase ACP process is used to promote ACP in different intensities over the cancer trajectory. The 1st phase involves systematically offering new patients an opportunity to select and prepare a surrogate medical decision-maker (MDM), after social work (SW) counseling and education. As a part of the intake, nurses ask the patient if they have an AD, if they would like assistance with ADs, and if they would like more information. Patients without a MPOA are routinely referred to SW unless they chose to opt-out. When meeting with SW, education includes the importance of appointing a MPOA and factors important to preparing MDM for their role. Questions used to support education are shown in Supplementary Table S1.29-31 In phase II, ideally coordinated with phase I, the oncologist/advance practice provider (APP) team discusses prognosis and treatment goals with the patient and his/her family caregiver. Phase III revolves around more in-depth goals of care discussions. All ACP communication is documented in electronic health record (EHR) ACP templates.29,30,32

Clinical experience suggests that this 3-phase ACP process is not routinely incorporated into standard-of-care as intended and does not appear to achieve the intended goal. Many patients do not meet with SW. Those who do have variable rates of MPOA document (MPOAD) completion, a surrogate measure of MDM preparation. A quality improvement project in the Gynecologic Oncology Center noted no increase in SW ACP visits or MPOAD completion. A number of factors were identified that might have contributed to the failure of the process.29-31

Here, we evaluate the impact of this standard-of-care systematic SW-driven process on patients’ selecting a MPOA, focusing on the 1st phase of the 3-phase process. To inform future work, we also evaluated factors associated with MPOAD completion and with changes in patients’ and family caregivers’ readiness for surrogate medical decision-making and knowledge of patients’ values and goals. Based on the literature, we anticipated that patients who had recurrent or metastatic cancer, were older, were non-Hispanic White, and/or had completed more years of education would exhibit greater ACP engagement and would demonstrate higher rates of selecting and preparing a MDM. We also anticipated that patients would demonstrate higher levels of ACP engagement over time as they processed the implications of their diagnosis and prognosis.2,4,15-28

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, USA. Research staff reviewed the roster of daily outpatient appointments from all Department of Gynecologic Oncology physicians to identify new patients and their potential protocol eligibility. Eligibility criteria included patients presenting with any stage of gynecologic cancer who were age 18 or older and spoke English or Spanish. At the time of their appointment and before meeting with SW, research staff met with potentially eligible individuals to introduce the study and its purpose:

This study is being conducted to see how well we prepare patients and their families to make medical decisions, together with their clinical team, that best suits their care needs. As a new patient at MD Anderson, your physician will be involving a social work counselor in your care so that you and a family member may learn how to choose and prepare both of you for making choices with your physician that best fits your needs.

Patients interested in learning more about the study were asked if they had an established MPOA or if not, a primary family caregiver who might be willing to participate. The family caregiver was defined as the unpaid individual most involved in providing direct assistance to the patient in activities of daily living. Assistance could be in the physical, emotional, psychological, and/or spiritual domains.33,34 Once permission to contact the MPOA or primary caregiver, as appropriate, was provided, more in-depth information about the study was discussed. Interested dyads who consented were then enrolled in the study.

Study processes were conducted in English or Spanish, at participant preference. Study measures that were not validated in Spanish were translated into neutral Spanish language versions, using established methods of forward and back translation.35-37 Questionnaires were conducted in person at baseline to evaluate potential factors associated with MPOAD completion and readiness for ACP. As part of routine institutional practice, patients without a MPOAD were then offered SW referrals regarding the selection of a MPOA. As few patients accepted the referral, we amended the protocol to develop and show a brief video to dyads without a MPOAD. The intent of the video was to engage patients and their caregivers in the process, support SW referral, and provide standardized education. At 3 months, all dyads were contacted to complete follow-up questionnaires to evaluate for new MPOAD completion and change in ACP readiness from that documented at baseline. Follow-up evaluations were conducted in person or by telephone, at the participant preference.

Highlighting the importance of the Gynecologic Oncology team placed on patients’ selecting and preparing a MPOA, there was a distinct but overlapping quality improvement initiative taking place during the study period. As part of this separate quality improvement initiative, physicians and/or their APPs provided a brief introduction to the concept of ACP and MPOA at the patient’s first appointment and encouraged SW referral.

Instruments

Self-Reported Health Literacy Questions

The “How confident are you filling out medical forms questions by yourself” (“Que tan seguro (a) se siente al llenar formas usted solo(a)?) question was used as a measure of health literacy.38

Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire Short Version

The Santa Clara strength of religious faith questionnaire short version is a 5 question self-report survey assessing the strength of religious faith and engagement used with individuals from multiple religious denominations. Higher scores indicate higher strength of religious faith.39-41

Decision-Making Preferences: The Control Preferences Scale

The control preferences scale42,43 was used to ascertain patients’ medical decision-making preferences with their physicians and families.42-45

Experience with Medical Decision-Making

Experience with MDM46 was evaluated with 3 questions:

Have you ever:

filled out an advance directive?

made life-threatening medical decisions for yourself?

made life-threatening medical decisions for someone else?

Patient’s Values and Goals for Medical Decision-Making for Serious Medical Illness

Patients were asked what would be important to them if they had a serious illness, as derived from the PREPARE website, developed to prepare diverse older adults for decision-making and ACP. Caregiver responses were modified to reflect surrogate decision-makers’ perception of the patient’s preferences.46-48

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs About MPOA: Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey

This validated tool evaluates individuals’ stage of readiness for ACP behaviors.48 We selected the 15-item version, with readiness and self-efficacy subscales. Subscale scores range from 1 to 5, with the total score composite of subscale scores.49,50

MPOAD Completion Status

Completion status was determined from scanned EHR documents and asking the patient or caregiver.

Willingness to Participate in Future ACP Discussions to Discuss Patients’ Values and Goals

This was assessed by response to the question: “How likely are you to participate in future discussions about your (the patient’s) values and goals important to medical decision-making?”, scored on a 5-point Likert scale.

Statistical Considerations

The analysis was descriptive. Baseline and change in patients and MPOAs responses were summarized and compared among 3 patient groups: (1) had MPOAD at baseline, (2) completed MPOAD between 1st visit in 3 months, and (3) did not complete MPOAD by 3 months. The continuous variables are summarized using means, standard deviation, median and range, and compared between or among groups using Wilcoxon rank sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical variables are summarized using counts and percentages and compared between or among groups using Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The percentages in the tables only reflect the percentage of information in the available data.

Results

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

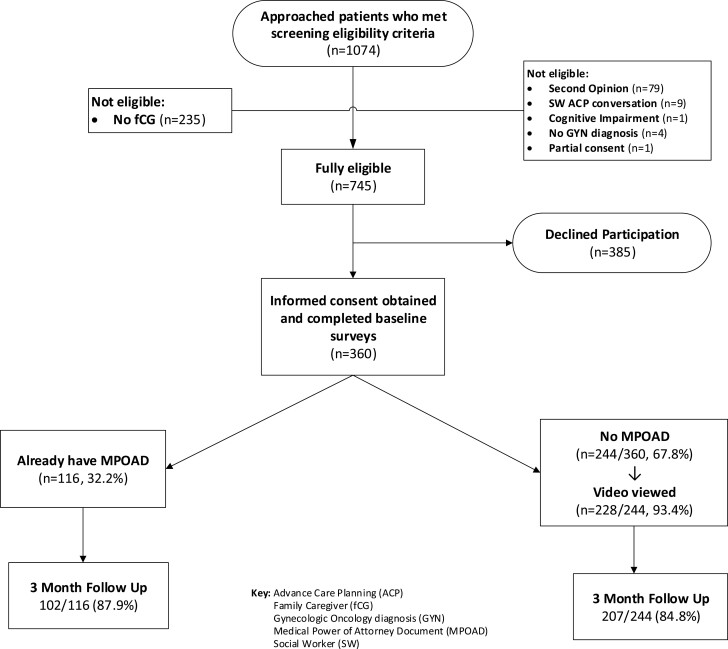

Of 1074 patients meeting prescreening criteria, 235 lacked a family caregiver and 94 were otherwise ineligible. Three hundred and eighty-five of 745 eligible patients (51.7%) declined to participate. The most common reasons were emotional and/or physical symptom distress (n = 150, 39.0%), study burden (n = 139, 36.1%), and lack of time (n = 90, 23.4%). Of 360 consenting dyads, 116 (32.2%) patients reported having a MPOAD at baseline. The remaining 244 dyads (67.8%) constituted the clinical process arm. Of these, 228 dyads (93.4%) viewed the video. Overall study retention for the primary outcome rate at 3 months was 309 dyads (85.8%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study flow chart, advance care planning (ACP), family caregiver (fCG) gynecologic oncology diagnosis (GYN), medical power of attorney document (MPOAD), and social worker (SW).

The most common diagnoses were ovarian (48.9%) and endometrial (35.6%) cancer. More than half had recurrent and 38.2% had metastatic disease (Table 1). The majority identified as White (88.9%), married (74.2%), and Christian (62.8%). Fifty (13.9%) were of Hispanic ethnicity. The study population had good functional status (92.0% with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status Scale [ECOG] performance status 0-1), was highly educated (83.1% >high school), and had an annual income ≥$100 000 USD (52.6%). Health literacy was “extremely” or “quite a bit” in 91.5%. Factors statistically associated with MPOAD at baseline were non-Hispanic ethnicity, White race, and retirement (Table 2). Of covariates, only greater experience with medical decision-making (Supplementary Table S2) and higher ACP patient engagement survey scores were associated with the presence of MPOADs at baseline (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic |

Total (N = 360) n (%) |

Patient without MPOAD (N = 244) n (%) |

Patient with MPOAD (N = 116) n (%) |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary cancer | NS | |||

| Cervical | 43 (11.9) | 35 (14.3) | 8 (6.9) | |

| Endometrial | 128 (35.6) | 85 (34.8) | 43 (37.1) | |

| Ovarian | 176 (48.9) | 116 (47.5) | 60 (51.7) | |

| Other | 13 (3.6) | 8 (3.3) | 5 (4.3) | |

| Disease status | NS | |||

| Localized | 107 (30.1) | 78 (32.5) | 29 (25) | |

| Regional | 85 (23.9) | 52 (21.7) | 35 (28.4) | |

| Metastatic | 136 (38.2) | 90 (37.5) | 46 (39.7) | |

| Staging inevaluable | 28 (7.9) | 20 (8.3) | 8 (6.9) | |

| Recurrent disease | NS | |||

| Yes | 190 (53.4) | 122 (50.8) | 68 (58.6) | |

| No | 166 (46.6) | 118 (49.2) | 48 (41.4) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Functional status (ECOG score) | NS | |||

| 0 | 217 (62.4) | 148 (62.4) | 69 (62.2) | |

| 1 | 103 (29.6) | 74 (31.2) | 29 (26.1) | |

| 2 | 23 (6.6) | 13 (5.5) | 10 (9) | |

| 3 | 5 (1.4) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Unknown | 12 | 7 | 5 |

aNS: P-value >.05.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of patients by status of MPOAD at baseline and their caregiver or Medical Power of Attorney.

|

Characteristic

|

All Patients

(N = 360) n (%) |

Patient without MPOAD

(N = 244) n (%) |

Patient with MPOAD

(N = 116) n (%) |

P value | All caregivers |

Caregiver or MPOA of patient without MPOAD

( N = 244) |

Caregiver or MPOA of patient with MPOAD

( N = 116) |

P value |

| Sex | NS | NS* | ||||||

| Female | 360 (100) | 244 (100) | 116 (100) | 103 (28.6) | 76 (31.1) | 27 (23.3) | ||

| Male | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 257 (71.4) | 168 (68.9) | 89 (76.7) | ||

| Ethnicity |

.0082 | .0104 | ||||||

| Hispanic | 50 (13.9) | 42 (17.2) | 8 (6.9) | 49 (13.6) | 41 (16.8) | 8 (6.9) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 310 (86.1) | 202 (82.8) | 108 (93.1) | 311 (86.4) | 203 (83.2) | 108 (93.1) | ||

| Race |

.0009 | .0061 | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 320 (88.9) | 207 (84.8) | 113 (97.4) | 313 (86.9) | 203 (83.2) | 110 (94.8) | ||

| Black | 23 (6.4) | 21 (8.6) | 2 (1.7) | 25 (6.9) | 21 (8.6) | 4 (3.4) | ||

| Other | 6 (1.7) | 16 (6.6) | 1 (0.9) | 22 (6.1) | 20 (8.2) | 2 (1.7) | ||

| Marital status | NS | NS | ||||||

| Married/partner | 267 (74.2) | 178 (73) | 89 (76.7) | 297 (82.5) | 206 (84.4) | 91 (78.4) | ||

| Single | 32 (8.9) | 22 (9) | 10 (8.6) | 37 (10.3) | 21 (8.6%) | 16 (13.8%) | ||

| Divorced | 35 (9.7%) | 27 (11.1%) | 8 (6.9%) | 19 (5.3%) | 11 (4.5%) | 8 (6.9%) | ||

| Widowed | 26 (7.2%) | 17 (7%) | 9 (7.8%) | 7 (1.9%) | 6 (2.5%) | 1 (0.9%) | ||

| Educational level | NS | .0459 | ||||||

| High school or less | 61 (16.9%) | 46 (18.9%) | 15 (12.9%) | 57 (15.9%) | 45 (18.6%) | 12 (10.3%) | ||

| Some college/graduate degree | 299 (83.1%) | 198 (81.1%) | 101 (87.1%) | 301 (84.1%) | 197 (81.4%) | 104 (89.7%) | ||

| Employment status* | .0001 | NS | ||||||

| Full time | 133 (37%) | 102 (41.8%) | 31 (27%) | 206 (57.9%) | 147 (61%) | 59 (51.3%) | ||

| Part time | 21 (5.8%) | 14 (5.7%) | 7 (6.1%) | 21 (5.9%) | 14 (5.8%) | 7 (6.1%) | ||

| Retired | 136 (37.9%) | 73 (29.9%) | 63 (54.8%) | 109 (30.6%) | 65 (27%) | 44 (38.3%) | ||

| Other | 69 (19.2%) | 55 (22.5%) | 14 (12.2%) | 20 (5.6%) | 15 (6.2%) | 5 (4.3%) | ||

| Annual income* | NS | .0426 | ||||||

| <$50 000 | 67 (19.7) | 52 (22.7) | 15 (13.5) | 48 (14.2) | 38 (16.6) | 10 (9.1) | ||

| $50 000-<$99 999 | 94 (27.6) | 61 (26.6) | 33 (29.7) | 91 (26.8) | 66 (28.8) | 25 (22.7) | ||

| ≥$100 000 | 179 (52.6) | 116 (50.7) | 63 (56.8) | 200 (59) | 125 (54.6) | 75 (68.2) | ||

| Religious affiliation | NS | NS | ||||||

| Atheist | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (1.4) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (2.6) | ||

| Catholic | 84 (23.3) | 61 (25) | 23 (19.8) | 82 (22.8) | 62 (25.4) | 20 (17.2) | ||

| Christian (not Catholic) | 226 (62.8) | 149 (61.1) | 77 (66.4) | 226 (62.8) | 148 (60.7) | 78 (67.2) | ||

| Not affiliated | 38 (10.6) | 28 (11.5) | 10 (8.6) | 34 (9.4) | 25 (10.2) | 9 (7.8) | ||

| Other | 12 (3.3) | 6 (2.5) | 6 (5.2) | 13 (3.6) | 7 (2.9) | 6 (5.2) | ||

| Health literacy | NS | |||||||

| Extremely | 248 (70.7) | 165 (69.3) | 83 (73.5) | |||||

| Quite a bit | 73(20.8) | 50 (21.0) | 23 (20.4) | |||||

| Somewhat | 14 (4) | 11 (4.6) | 3 (2.7) | |||||

| A little | 13 (3.7) | 10 (4.2) | 3 (2.7) | |||||

| Not at all | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) |

P-value significant at ≤0.05 for bolded values.

*NS: P-value >.05.

Table 3.

Patient advance care planning engagement scores at baseline and MPOAD completion status.

| Score, mean ±SD and median (range) | All Patients (N = 360) | Present at baseline (N = 100) | None at baseline, present at 3 months (N = 19) | None at baseline,not present at 3 months (N = 187) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score (0-10) |

7.7 ± 1.82 8.03 (2, 10) |

8.7 ± 1.38 9.19 (4.11, 10) |

8.42 ± 0.87 8.33 (6.89, 9.67) |

7.13 ± 1.78 7.39 (2.11, 10) |

<.0001 |

| Self-efficacy subscale (0-5) |

4.22 ± 0.87 4.5 (1, 5) |

4.6 ± 0.55, 4.83 (2, 5) | 4.61 ± 0.44, 4.83 (3.67, 5) | 4.02 ± 0.91, 4.17 (1, 5) | <.0001 |

| Readiness subscale (0-5) |

3.48 ± 1.11 3.67 (1, 5) |

4.1 ± 0.96 4.44 (1.57, 5) | 3.81 ± 0.66 4 (1.89, 4.67) |

3.12 ± 1.04 3.22 (1, 5) | <.0001 |

Note: Frequency missing = 17.

MPOAD Completion

Of 244 patients reported to be without a MPOAD at baseline, 20 (8.2%) completed a MPOAD by 3 months. One hundred and forty-three of 207 patients with follow-up data (69.01%) did not meet with SW about ACP. Completers were more likely to have met with SW than individuals who did not 12/20 (60%) vs. 52/187 (27.8%), (odds ratio: 3.894, 95% CI, 1.506, 10.070, P = .003).

Values and Goals for Medical Decision Making

At baseline, 14.5% of patients indicated their values and goals for medical decision-making to be “live as long as possible,” 53.6% selected “trial of time,” 17.3% preferred to “focus on quality of life,” and 14.5% were unsure. At follow-up, corresponding figures were 24.4%, 46.2%, 18.5%, and 10.9%, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patients’ values and goals for medical decision-making by MPOAD completion status.

| Value/goal | All patients (N = 360) n (%) | Present at baseline (N = 100) n (%) | None at baseline, present at 3 months (N = 19) n (%) | None at baseline, not present at 3 months (N = 187) n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | NS * | ||||

| Try to live as long as possible | 52 (14.5) | 13 (13) | 2 (10.5) | 29 (15.7) | |

| Try treatments for a period of time, but I don’t want to suffer | 192 (53.6) | 53 (53) | 11 (57.9) | 106 (57.3) | |

| Focus on my quality of life | 62 (17.3) | 22 (22) | 0 (0) | 28 (15.1) | |

| I am not sure | 52 (14.5) | 12 (12) | 6 (31.6) | 22 (11.9) | |

| Follow-up | NS * | ||||

| Try to live as long as possible | 58 (24.4) | 18 (21.2) | 4 (26.7) | 36 (26.5) | |

| Try treatments for a period of time, but I do not want to suffer | 110 (46.2) | 46 (54.1) | 3 (20) | 60 (44.1) | |

| Focus on my quality of life | 44 (18.5) | 14 (16.5) | 6 (40) | 23 (16.9) | |

| I am not sure | 26 (10.9) | 7 (8.2) | 2 (13.3) | 17 (12.5) |

P-value significant at ≤0.05 for bolded values.

*NS: P-value >.05.

Patients did not differ in their reported values and goals for decision-making at baseline or follow-up by MPOAD completion status (Table 4); nor did their family caregivers/MPOAs vary in their perceptions of the patient’s values and goals by MPOAD completion status at these time points (data not shown). Correlation between the patient’s values and goals and their caregiver’s/MPOA’s perception was very weak at baseline, improving to moderate at follow-up (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, respectively). The correlation between the patient’s values and goals for medical decision-making reported at baseline with that reported at follow-up was weak (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of patient’s values and goals for medical decision-making between baseline and follow-up.

| Value/goal | Try to live as long as possible | Try treatments for a period of time, but I don’t want to suffer | Focus on my quality of life | I am not sure | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Try to live as long as possible | 22 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 37 |

| Try treatments for a period of time, but I do not want to suffer | 20 | 84 | 22 | 9 | 135 |

| Focus on my quality of life | 11 | 10 | 14 | 3 | 38 |

| I am not sure | 4 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 26 |

| Total | 57 | 110 | 44 | 25 | 236 |

Notes: Frequency missing = 124.

Spearman correlation coefficients = 0.2376, P = .0002.

When looking at the change in values and goals from baseline to follow-up, more patients moved to endorse life-prolonging interventions than to focus on the quality of life. A total of 236 patients finished the survey at both baseline and follow-up. One hundred and twenty-seven patients (53.8%) remained stable in their choice, 49 (20.8%) indicated a preference for less aggressive, and 60 (25.4%) changed care preferences to more aggressive care (Table 5). Sixty-one dyads (32%) remained stable in their preferences and perception of the patient’s values and goals for medical decision-making (data not shown).

ACP Engagement Survey Scores

Total scores for the group overall indicated moderately high levels of ACP engagement, with scores for self-efficacy higher than those for readiness. Patients who had a MPOAD at baseline or by 3 months had statistically significant higher total and subscale scores than those who did not complete a MPOAD (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in change from baseline to follow-up for the total group or 3 subgroups in total score or subscale scores (Table 6). Most patients (198/241, 82.2%) and their caregivers/MPOAs (223/243, 91.7%) indicated they were fairly or extremely likely to participate in future ACP discussions.

Table 6.

Change in patient advance care planning engagement scores from baseline to follow-up by MPOAD completion status.

| Score. Mean ± SD, median (range) | All patients (N = 360) | Present at baseline (N = 100) | None at baseline, present at 3 months (N = 19) | None at baseline,not present at 3 months (N = 187) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score (0-10) |

0.48 ± 1.5 0.29 (−4.78, 4.67) |

0.38 ± 0.99 0.06 (−2.05, 4.07) |

0.6 ± 1.42 0.72 (−2.22, 2.78) |

0.54 ± 1.76 0.39 (−4.78, 4.67) |

NS* |

| Self-efficacy subscale (0-5) |

0.19 ± 0.83 0 (−2.67, 3.33) |

0.13 ± 0.42, 0 (−1.17, 1.17) |

0.04 ± 0.58 0 (−1.03, 1) |

0.24 ± 1.02 0.17 (−2.67, 3.33) |

NS |

| Readiness subscale (0-5) | 0.29 ± 0.95 0.11 (−2.44, 3.32) |

0.25 ± 0.76 0 (−1.56, 3.32) |

0.56 ± 1.09 0.89 (−1.22, 2.78) |

0.29 ± 1.04 0.22 (−2.44, 2.89) |

NS |

*NS: P > .05.

Discussion

This multidisciplinary, standard of care SW-driven process did not engage our study population, despite the incorporation of a video providing strong provider endorsement and standardized educational content. This is surprising because there was an over-representation of individuals with demographics associated with AD completion.18,25,26 Equally, if not more surprising, is the lack of participant engagement, given moderate to high ACP patient engagement survey scores. Moreover, almost 40% of the women had metastatic disease and more than half had recurrent cancer, both of which should have heightened the salience of ACP.51,52

Many factors could explain the failure of institutional processes to engage these women to self-advocate for periods of incapacity for medical decision-making. Among them are dose intensity, components, and/or timing of the procedures. The overwhelming majority of patients had no or limited SW contact. Many had no or minimal physician follow-up.29,30 As our institution is a comprehensive cancer center, often people come for a second opinion and then remain in their local community. Some are quite ill, limiting their ability to return. Timing potentially influenced patient engagement, given multiple competing priorities and emotional distress associated with a new diagnosis of cancer. Our findings reinforce those of others that ACP is a process over time.1,11,48,53 Potential next steps might include a focus on patients with higher ACP patient engagement scores.

Our exploratory data yielded other unexpected results. First, there was no change in readiness or self-efficacy along the ACP behavior spectrum over the study period. This potentially speaks to the dose intensity of the process. Second, there was a poor correlation between patients’ self-assessed values and goals for medical decision-making at baseline, although caregivers’/MPOAs’ perception of the patient’s stated values and goals improved to moderate at 3 months. Finally, while 53.8% of patients remained stable in their values and goals for medical decision-making over the study period, more of the remaining patients moved to “live as long as possible” than to “focus on quality of life” (P = .005). This is remarkable given the disease trajectory toward death many were facing.

Study strengths included its pragmatic nature centered around standard-of-care, strong study endorsement by the Gynecologic Oncology Center providers, its bilingual nature, and high retention. Recruitment of Hispanic women was consistent with their representation in the Center population.

Study limitations included minimal diversity in the study population and difficulty recruiting because of reported physical and emotional distress and other prioritized needs. Accordingly, recruitment might have been higher if the timing had been delayed to a later visit. This would offer a different recruitment challenge, given the limited follow-up for much of the population.29,30

As almost half of the patients changed their values and goals for care over a relatively brief period, elucidating factors associated with the change in direction of care, as contrasted to those with stable preferences, is crucial to developing new paradigms of ACP. It also raises the question that ACP might better be directed at helping patients and surrogate MDMs prepare for “just in time” decision-making.54 Exploring emotional and cognitive components that influence prognostic understanding and potential care outcomes might be fruitful.55 Better understanding of these factors might allow for more effective intervention designs tailored to individual patients.

Conclusion

A systematic SW-driven intervention did not engage new patients with gynecologic malignancies presenting to a comprehensive cancer center to select and prepare MPOAs, important to the promotion of goal-concordant care. Change in cancer care preferences was common. The correlation of caregivers’ perception of patients’ treatment goals with patients’ reports was moderate at best. To better promote goal-concordant care, new paradigms of ACP are needed to prepare patients and their surrogate MDMs for more dynamic medical decision-making than that afforded by ADs and traditional ACP approaches.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brittany Cullen, Kate Krause, MLIS, research coordinators, Gynecologic Oncology Center staff, and the patients and families who made this study possible.

Contributor Information

Donna S Zhukovsky, Department of Palliative Care Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Pamela Soliman, Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Diane Liu, Department of Biostatistics, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Margaret Meyer, Department of Social Work, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Ali Haider, Department of Palliative Care Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Yvonne Heung, Department of Palliative Care Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Susan Gaeta, Department of Emergency Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Karen Lu, Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Karen Stepan, Department of Medical Affairs, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Penny Stanton, Department of Palliative Care Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Alma Rodriguez, Department of Lymphoma-Myeloma, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Eduardo Bruera, Department of Palliative Care Rehabilitation and Integrative Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Hearst Clinical Innovator Award.

Conflict of Interest

Pamela Soliman disclosed grants to the institution from Novartis and Incyte. Dr Soliman also received payments from Amgen and Eisai Medical Research Inc., as well as Medscape as a speaker/preceptorship. The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: D.S.Z., P.Soliman, S.G., K.S., A.R., E.B. Provision of study material or patients: P.Soliman, K.L. Collection and/or assembly of data: D.S.Z., P.Stanton, A.H., Y.H. Data analysis and interpretation: D.L. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. US: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Clinician-patient communication and advance care planning. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Chap. 3. US: The National Academies Press; 2015:117-220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Introduction. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press; 2015:21-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Institute of Medicine (IOM). Summary. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. The National Academies Press; 2015:1-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peppercorn JM, Smith TJ, Helft PR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: toward individualized care for patients with advanced cancer. Clin Oncol. 2011;29(6):755-760. 10.1200/jco.2010.33.1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Quality Forum. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care—A Consensus Report. Updated April, 2012. Accessed October 11, 2022. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%E2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx

- 7. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W.. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345-c1345. 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA.. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477-489. 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health: medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bestvina CM, Polite BN.. Implementation of advance care planning in oncology: a review of the literature. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(10):657-662. 10.1200/jop.2017.021246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Toguri JT, Grant-Nunn L, Urquhart R.. Views of advanced cancer patients, families, and oncologists on initiating and engaging in advance care planning: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):150. 10.1186/s12904-020-00655-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. California HealthCare Foundation. Final Chapter: Californians’ Attitudes and Experiences with Death and Dying. Updated February 9, 2012. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.chcf.org/publication/final-chapter-californians-attitudes-and-experiences-with-death-and-dying/

- 13. Clements JM. Patient perceptions on the use of advance directives and life prolonging technology. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26(4):270-276. 10.1177/1049909109331886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ.. Advance directives in critically ill cancer patients. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2000;12(3):373-383. 10.1016/s0899-5885(18)30102-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yennurajalingam S, Noguera A, Parsons HA, et al. A multicenter survey of Hispanic caregiver preferences for patient decision control in the United States and Latin America. Palliat Med. 2013;27(7):692-698. 10.1177/0269216313486953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blank RH. End-of-life decision making across cultures. J Law Med Ethics. Summer 2011;39(2):201-214. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, Michel V, Azen S.. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA. 1995;274(10):820-825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khosla N, Curl AL, Washington KT.. Trends in engagement in advance care planning behaviors and the role of socioeconomic status. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(7):651-657. 10.1177/1049909115581818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saeed F, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, et al. Is annual income a predictor of completion of advance directives (ads) in patients with cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(5):402-407. 10.1177/1049909118813973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kelley CG, Lipson AR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL.. Advance directive use and psychosocial characteristics: an analysis of patients enrolled in a psychosocial cancer registry. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(4):335-341. 10.1097/ncc.0b013e3181a52510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelly EP, Henderson B, Hyer M, Pawlik TM.. Intrapersonal factors impact advance care planning among cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(8):907-913. 10.1177/1049909120962457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Enguidanos S, Ailshire J.. Timing of advance directive completion and relationship to care preferences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(1):49-56. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoe DF, Enguidanos S.. So help me, God: religiosity and end-of-life choices in a nationally representative sample. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(4):563-567. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Portanova J, Ailshire J, Perez C, Rahman A, Enguidanos S.. Ethnic differences in advance directive completion and care preferences: what has changed in a decade?. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(6):1352-1357. 10.1111/jgs.14800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Inoue M. The influence of sociodemographic and psychosocial factors on advance care planning. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2016;59(5):401-422. 10.1080/01634372.2016.1229709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hong M, Kim K.. Advance care planning among ethnic/racial minority older adults: prevalence of and factors associated with informal talks, durable power of attorney for health care, and living will. Ethn Health. 2020;27(2):453-462. 10.1080/13557858.2020.1734778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, Laux JP.. Completion of advance directives among U.S. Consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(1):65-70. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, Smith AK.. Low completion and disparities in advance care planning activities among older Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1872-1875. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhukovsky DS, Soliman PT, Mathew B, et al. Systematic approach to selecting and preparing a medical power of attorney in the gynecologic oncology center. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(12):e1092-e1097. 10.1200/jop.19.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhukovsky DS, Haider A, Williams JL, et al. An integrated approach to selecting a prepared medical decision-maker. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(6):1305-1310. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sudore RL, Fried TR.. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256-261. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stepan K, Bashoura L, George M, et al. Building an infrastructure and standard methodology for actively engaging patients in advance care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15(12):e1085-e1091. 10.1200/jop.18.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glajchen M. The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. J Support Oncol. 2004;2(2):145-155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Cancer Institute. Pdq-nci’s Comprehensive Database: Caregiver. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/pdq

- 35. Cull A SM, Bjordal K, Aaronson N, West K, Bottomley A.. EORTC Quality of Life Group Translation Procedure. 2nd ed. 2002. Accessed October 11, 2022. ipenproject.org/documents/methods_docs/Surveys/EORTC_translation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maneesriwongul W, Dixon JK.. Instrument translation process: a methods review. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(2):175-186. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Acquadro C, Conway K, Hareendran A, Aaronson N.. Literature review of methods to translate health-related quality of life questionnaires for use in multinational clinical trials. Value Health. 2008;11(3):509-521. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00292.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sarkar U, Schillinger D, López A, Sudore R.. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):265-271. 10.1007/s11606-010-1552-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Plante TB. The Santa Clara strength of religious faith questionnaire. Pastoral Psychol. 1997;45(5):375-387. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Plante TG, Vallaeys CL, Sherman AC, Wallston KA.. The development of a brief version of the Santa Clara strength of religious faith questionnaire. Pastoral Psychol. 2002;50(5):359-368. 10.1023/A:1014413720710 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plante TG. The Santa Clara strength of religious faith questionnaire: assessing faith engagement in a brief and nondenominational manner. Religions. 2010;1(1):3-8. 10.3390/rel1010003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Degner LF, Sloan JA.. Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(9):941-950. 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90110-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Degner LF, Sloan JA, Venkatesh P.. The control preferences scale. Can J Nurs Res. 1997;29(3):21-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Davison BJ, Gleave ME, Goldenberg SL, Degner LF, Hoffart D, Berkowitz J.. Assessing information and decision preferences of men with prostate cancer and their partners. Cancer Nurs. 2002;25(1):42-49. 10.1097/00002820-200202000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Singh JA, Sloan JA, Atherton PJ, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the control preferences scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688-696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(4):674-686. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sudore RL FD. Prepare: UCSF Office of Technology Management. Accessed October 11, 2022. https://prepareforyourcare.org/

- 48. Sudore RL, Stewart AL, Knight SJ, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire to detect behavior change in multiple advance care planning behaviors. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72465. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, Sudore RL.. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):355-365. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, et al. Measuring advance care planning: optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(4):318669-681.e8. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Díaz-Montes TP, Johnson MK, Giuntoli RL 2nd, Brown AJ.. Importance and timing of end-of-life care discussions among gynecologic oncology patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(1):59-67. 10.1177/1049909112444156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Croom AR, Hamann HA, Kehoe SM, Paulk E, Wiebe DJ.. Illness perceptions matter: understanding quality of life and advanced illness behaviors in female patients with late-stage cancer. J Support Oncol. 2013;11(4):165-173. 10.12788/j.suponc.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, O’Leary JR.. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1547-1555. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02396.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sudore RL, Fried TR.. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256-261. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Baker JN, Barfield R, Hinds PS, Kane JR.. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: the individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(3):245-254. 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.