Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) represent a pathological subtype of breast cancer, which are characterized by strong invasiveness, high metastasis rate, low survival rate, and poor prognosis, especially in patients who have developed resistance to multiline treatments. Here, we present a female patient with advanced TNBC who progressed despite multiple lines of treatments; next-generation sequencing (NGS) was used to find drug mutation targets, which revealed a coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6 (CCDC6)-rearranged during transfection (RET) gene fusion mutation. The patient was then given pralsetinib, and after one treatment cycle, a CT scan revealed partial remission and adequate tolerance to therapy. Pralsetinib (BLU-667) is a RET-selective protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor that can inhibit the phosphorylation of RET and downstream molecules as well as the proliferation of cells expressing RET gene mutations. This is the first case in the literature of metastatic TNBC with CCDC6-RET fusion treated with pralsetinib, an RET-specific antagonist. This case demonstrates the potential efficacy of pralsetinib in cases of TNBC with RET fusion mutations and suggests that NGS may reveal new opportunities and bring new therapeutic interventions to patients with refractory TNBC.

Keywords: breast cancer, CCDC6-RET, pralsetinib, response

This article reports the first case in the literature of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) with coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6-rearranged during transfection (RET) fusion treated with pralsetinib, an RET-specific antagonist. This case demonstrates the potential efficacy of pralsetinib in cases of TNBC with RET fusion mutations and suggests that next-generation sequencing may reveal new opportunities and bring new therapeutic interventions to patients with refractory TNBC.

Key Points.

This case report is believed to be the first demonstrating clinical efficacy of pralsetinib in a patient with multidrug-resistant breast cancer with a coiled-coil domain-containing protein 6-rearranged during transfection mutation.

The patient showed obvious disease remission in the targeted treatment of pralsetinib.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignant tumor with the highest incidence in women worldwide1; the incidence of female breast cancer accounted for 30% of the total incidence of female malignancies in 2020; thus, posing a grave threat to the lives of women. Triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) is the subtype of breast cancer that lacks the expression of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (EGFR2), (HER2) and accounts for 12%-17% of patients with breast cancer.1 Due to the lack of therapeutic targets, it shows a poor response rate to endocrine and anti-HER2 therapies, especially in advanced metastatic patients with a low complete remission rate, easy drug resistance, and ineffective clinical treatment after attaining resistance. As most patients have a poor clinical prognosis, genetic evaluation for advanced metastatic TNBC patients to understand drug resistance mechanisms, and uncover effective therapeutic targets should be undertaken.

Rearranged during transfection RET is a single-channel transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) whose fusion-related structural alterations lead to ligand nondependent dimerization and constitutive kinase activation, drive oncogenic signaling cascades, promote cell survival and proliferation2 and are associated with cellular aberrations and the development of malignancies. Most RET fusions lack the N-terminal and transmembrane structural domains, resulting in aberrant localization of the fusion product, and hence, preventing its normal intracellular transport and destruction.3 It mainly includes kinesin family member 5b (KIF5B)-RET, CCDC6-RET, nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-RET, and tripartite motif-containing 33 (TRIM33)-RET3 (Fig. 1). RET proto-oncogene fusion is found in 6.8% and 1%-2% of thyroid and lung cancers, while its occurrence in breast cancer is only 0.08%, which is a rare genetic mutation.4-6 It has been discovered that RET gene mutations are mutually exclusive with EGFR, HER2, v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1(BRAF), and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations along with echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (EML4-ALK) and Recombinant C-Ros Oncogene 1 (ROS-1) rearrangements, suggesting that they may also be a viable therapeutic target for treating such malignancies.7

Figure 1.

Characterization of RET/PTC oncogenicity. Schematic diagram highlighting important aspects of the proposed RET/PTC oncogenicity model. Full-length, endogenous, RET transcript is translated and targeted to the plasma membrane. On activation, it is internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis, activates ERK from endosomes, and finally is targeted to the lysosome for degradation. PTCl is released into the cytoplasm directly after translation. From here, it avoids degradation and promotes ERK.1/2 phosphorylation. PTC3 is also delivered directly to the cytoplasm after translation, where it mediates strong phosphorylation of STATI, interacts with CBL-b, and may be degraded by the proteasome. Width arrows, relative levels of transcript encoded by RET, CCDC6, and NCOA4. Dashed arrows with a “P,” regulation by phosphorylation. Reprinted from Cancer Research 2009;69(11):4861-4869, with permission from AACR.3

Pralsetinib is an RET receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor that inhibits RET and downstream molecular phosphorylation; thus, limiting the proliferation of the cells containing RET gene variation, and has demonstrated strong therapeutic effectiveness and an excellent safety profile in early clinical investigations.8 It has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for usage in RET fusion positive, previously systemically treated locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung and thyroid cancers. It is also the first RET inhibitor to be approved in China. However, as a new RET inhibitor, its efficacy in patients with breast cancer with RET fusion has not been observed to date.

In this case report, we have described a patient with RET fusion-positive advanced TNBC, who received a targeted therapy of pralsetinib (400 mg/day) and was evaluated for efficacy at PR by the end of one treatment cycle and is currently receiving maintenance therapy. It also demonstrates that next-generation sequencing (NGS) of patients with TNBC after resistance to multiple lines of therapy can be an effective method for identifying novel therapeutic agents. As pralsetinib displays significant efficacy and good tolerability in breast cancer patients with RET fusion mutations, further trials can be conducted to determine its clinical utility.

Patient Story

The patient was a 36-year-old married Asian lady who had menarche at age 15, was premenopausal, and denied having a family history of comparable genetic illnesses. The current medical diagnosis of advanced TNBC with RET gene fusion. On June 6, 2019, the patient visited our hospital for the first time due to “significantly enlarged cervical lymph nodes with left facial edema.” Physical examination at the time of admission showed significant edema on the left side of the face along with multiple hard, red, and swollen palpable masses in the left breast. A CT scan of the neck and chest showed left breast cancer with extensive lymph node, thoracic soft tissue, and bone metastases.

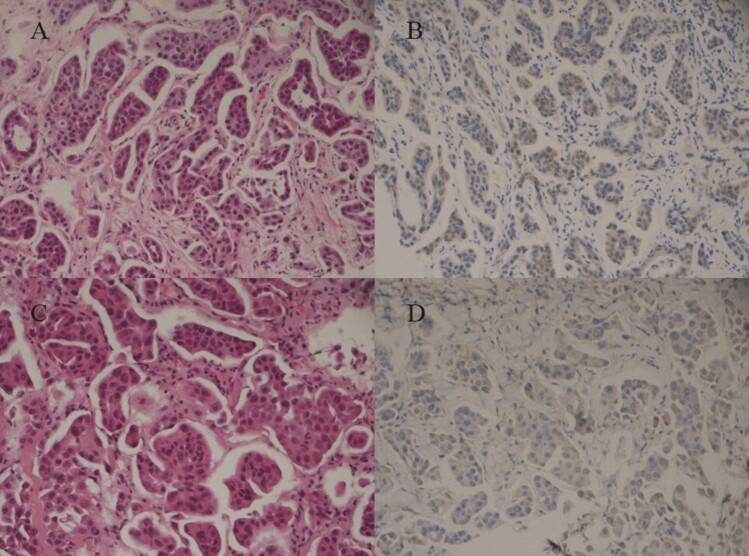

Histopathologic evaluation of the left breast puncture showed invasive carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry results were: ER (−), PR (+5%), p53 (−), HER (1+), Ki-67 (10%), CK (+), E-cad (+), S-100 protein and myosin heavy chain (SMMS-1) (−), BRCA1(−) (Fig. 2A and 2B). The tumor markers CEA are: 63.65 ng/mL; CA125: 332.70 U/mL, CA153: 140.60 U/mL, and Neuron-specific enolase (NSE): 21.00 ng/mL. The patient was diagnosed with “invasive TNBC in the left breast (pT4N3M1 IV)” in conjunction with the results of puncture histopathology, immunohistochemistry, and imaging studies.

Figure 2.

(A) and (B) show the first pathological puncture image of the patient on June 6, 2019 (A: hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×2Q0; B: immunohistochemical staining, original magnification ×200). (C) and (D) show the re-pathological puncture images of patient 202l.12(C: hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200; D: immunohistochemical staining, original magnification ×2Q0).

After confirming the diagnosis, considering a higher degree of malignancy and ineffective endocrine and targeted therapy drugs for TNBC, the patient was given 5 cycles of first-line chemotherapy from June 2019. The drug regimen was paclitaxel 270 mg (d1)+ carboplatin 700 mg (d1 q3w). On August 2019, CT reexamination showed PR. However, a repeat CT on October 2019 showed progressive disease (PD). Subsequently, second-line chemotherapy was started, and the specific regimen was epirubicin 120 mg (d1)+cyclophosphamide 0.9 g (d1 q3w). After 3 cycles of treatment, the patient discontinued the drug due to severe myelosuppression. Later, sintilimab (IBI308: a recombinant humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody developed in China that blocks interactions between PD-1 and its ligands) 200 mg (q3w) was administered. Review of the patient after 2 cycles of treatment showed rapid PD. However, the patient’s treatment was affected by the unexpected COVID-19 pandemic and was given 6 cycles of “gemcitabine 300 mg (d1,8) + carboplatin 600 mg (d1, q3w)” treatment at a local hospital. A repeat CT on September 2020 revealed that the disease had PD, and she was seen again at our hospital for further treatment. The next line of treatment was “vinorelbine 40 mg (d1-8) + carboplatin 600 mg (d1) + avastin 400 mg (d1, q3w)” for 4 cycles of disease progression. Afterward, the patient took eribulin 200 mg (d1-8) + anlotinib hydrochloride (a multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor [TKI]) 8 mg (d1-14, q3w) for 6 treatment cycles; a repeat CT again showed PD. Another histopathological biopsy of the left breast mass was performed, and although the pathological diagnosis was invasive ductal carcinoma, when combined with immunohistochemistry, the diagnosis was given as invasive micropapillary carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry results were: ER (−), PR (−), B-Catenin (+), P120 (membrane +), HER2 (1+), P63 (−), WHC (−), Ki-67 (25%), and AR (−) (Fig. 2C and 2D). After multiple drug resistance, no significant change was observed between the pathological reexamination and that conducted before initiating the treatment. Combined with the patient’s treatment, 3 cycles of anlotinib hydrochloride 8 mg (d1-14) +niraparib 300 mg (q.d.) were started on January 2022. A subsequent CT scan after 3 cycles showed disease progression.

At this time, the patient had a poor response effect after multiple lines of treatment, with numerous lymph node metastases in the neck, chest, and armpit, chest skin ulcerations, as well as multiple bone, liver, and spleen metastases (Fig. 3A), the tumor markers CEA, CA-125, and CA-153 were significantly elevated (Table 1). The patient also developed drug resistance after multiple lines of treatment, thus, facing the dilemma of using other treatment options.

Figure 3.

(A) shows images of patients before treatment with pralsetinib. (B) shows images of patients after 1 cycle of treatment with pralsetinib.

Table 1.

Changes in hematological parameters of partial response efficacy and safety before and after treatment with pralsetinib in patients.

| Before Pralsetinib | May 2022 | July 2022 | Jan 2023 | Reference value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor markers (efficacy) | CEA(ng/mL) | 697.44 | 273.30 | 16.09 | 9.60 | 0-5 |

| CA-125(U/mL) | 1806.80 | 82.40 | 17.80 | 22.10 | 0-35 | |

| CA153(U/mL) | 292.50 | 165.80 | 22.50 | 9.00 | 0-31.3 | |

| AEs (safety) | WBC(10*9/L) | 4.73 | 1.86 | 3.46 | 2.54 | 3.5-9.5 |

| Plt(10*9/L) | 208 | 59 | 251 | 173 | 125-350 | |

| ALT(U/L) | 21.3 | 60.4 | 29.8 | 47.1 | 7-40 | |

| AST(U/L) | 27.3 | 48.3 | 37.7 | 34.7 | 13-35 | |

Abbreviations: AEs: adverse events; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CA-125: cancer antigen 125; CA-153: cancer antigen 153; WBC: white blood cell; PLT: platelet; ALT: alanine transaminase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase.

Molecular Tumor Board

In order to find drug therapeutic targets, a whole-target genetic test-tissue version of solid tumors was performed in April 2022, in which a CCDC6-RET gene fusion mutation was found (Berry Oncology, 654 oncogenic driver gene panel). Sequences support of CCDC6-RET fusion was detected by DNA-Seq (Fig. 4A) and RNA-Seq (Fig. 4B) methods. Schematic of genome rearrangement of CCDC6-RET involving fusion breakpoints at mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4C). The fusion of CCDC6-RET in tissue was determined which was formed by exon1 fragment of CCDC6 and exon12-exon20 fragment of RET (Fig. 4A and 4C). The rearrangement was further verified by RNA fusion plate hybrid capture sequencing (Berry Oncology Corporation) technology to confirm the existence of CCDC6-RET (C1: R12) fusion mutation (Fig. 4B and 4C). In addition, the programmed cell death-ligand 1(PD-L1) expression was detected in 95% and 95% of Tumor cell Proportion Score (TPS) and Combined Positive Score (CPS) patients (Fig. 5), whereas the tumor Protein p53(TP53) mutation frequency was 11.67%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Identification and verification of CCDC6->RET fusion. (A) DNA sequencing reads indicating CCDC6 and RET fusion regions were visualized by the Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV) software. The fusion breakpoints are localized at chrlO: q21.2: 61,641,221 and chrlO: ql 1.21: 43,611,849, respectively. (B) RNA sequencing reads indicating CCDC6 and RET fusion regions were visualized by the Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV) software. The fusion breakpoints are localized at chrlO: q21.2: 61,665,880 and chrlO: qll.21: 43,612,032, respectively. (C) Schematic of genomic rearrangement involving the fusion breakpoints in mRNA and protein level. The transcript resulted in exons 1 of CCDC6 containing DUF2046 domains fused to exons 12-20 of RET including PK_Tyr_Ser-Thr domain. Pink, CCDC6; Blue, RET.

Figure 5.

The results of PD-Ll testing (immunohistochemical staining, original magnification ×400).

Based on the patient’s gene sequencing results and previous treatment options, the patient was given a targeted therapy with pralsetinib (400 mg q.d.) (Fig. 6). Pralsetinib, a specific RET receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitor, is currently approved by the FDA for treating RET fusion positive as well as previously treated for locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung and thyroid cancers and is also the first RET inhibitor approved for marketing in China. In thyroid cancer and NSCLC with RET fusion mutation, the objective response rate (ORR) of pralsetinib treatment is as high as 57%, thereby proving that it can be an effective treatment modality for patients with RET fusion mutation. To the best of our knowledge, its efficacy in breast cancer patients with RET fusion mutation has never been reported to date. Our patient was treated with pralsetinib for 4 weeks.

Figure 6.

Patient overall treatment process schematic.

Patient Update

In May 2022, after one cycle of pralsetinib, the primary tumor of the patient and metastatic foci were significantly reduced (Fig. 3B), the tumor markers CEA, CA-125, and CA-153 were significantly decreased, and PR was evaluated based on the patient’s CT examination results (Table 1). However, the patient displayed grade III bone marrow suppression and mild hepatic impairment after one cycle of medication. After the patient’s condition improved, the dosage of the drug was reduced and adjusted to 300 mg/day. In July 2022, the patient’s review CT after 3 cycles of treatment showed that the tumor liver and spleen metastases disappeared, and the primary foci and lymph node metastases in the neck were slightly reduced compared with the last review. The tumor markers CEA, CA-125, and CA-153 continued to decrease, with CA-125 and CA-153 returning to normal range. The patient tolerated well after drug dose adjustment. The patient was last reviewed in January 2023 and was evaluated for stable disease based on the test results and is currently on pralsetinib maintenance therapy (Table 1).

Discussion

We have presented a case of metastatic TNBC with RET fusion which is a very rare occurrence. The treatment was well tolerated, and currently, the patient has stable disease. The maintenance treatment was continued. This is the first reported case of metastatic TNBC with CCDC6-RET fusion treated with RET-specific antagonists pralsetinib to date.

Anthracycline/taxane-based chemotherapy in conjunction with carboplatin is the primary treatment option in women with TNBC.9 However, chemotherapy-resistant TNBC is associated with a very poor prognosis.10 In addition, immune checkpoint inhibitors can also be used to treat TNBC, evaluating PD-L1 expression in metastatic TNBC can predict the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors.11,12 Approximately, 15%-20% of TNBC cases are associated with either Breast-Cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 germline mutations. Thus, precise evaluation of BRCA mutations in metastatic breast cancer can identify patients who might benefit from PARP (poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) inhibitor therapy (TNBC or HER2-negative, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer).13 Guidelines for germline BRCA mutation testing in early breast cancer cases have been developed by various organizations, and most guidelines recommend evaluating all TNBC patients <50 years.9

In this case, after the patient tested negative for BRCA germline mutations, first-line chemotherapy was given. After the disease progressed, the patient received second-line chemotherapy, which was followed by immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy due to serious adverse reactions; all further multiple therapeutic interventions were ineffective.

After the patient became resistant to multiple drugs, NGS was conducted to find possible targets to seek new drug opportunities. The sequencing showed a CCDC6-RET gene fusion mutation. According to recent literature, TNBC with CCDC6-RET gene fusion mutation was reported for the first time, while only one case of RASGEF1A-RET fusion TNBC was reported before.6 CCDC6-RET has also been previously identified in lung and thyroid carcinomas and is the most common RET fusion observed in papillary thyroid carcinoma.14,15 RET-altered cancers were initially treated with various multikinase inhibitors showing RET-inhibiting activity, but their efficacy was not adequate due to significant toxicity and impact on health-related quality of life, eventually leading to their discontinuation.16

In 2020, the FDA approved 2 highly potent and selective RET inhibitors: selpercatinib and pralsetinib. Pralsetinib is also the first RET inhibitor approved in China and targets RET-mutated genes with high selectivity and precision, as well as displays a broader and persistent anti-tumor effect on RET-mutated cancer patients. Simultaneously, by inhibiting primary and secondary mutations, pralsetinib can prevent and overcome clinical resistance. Because most patients tolerated pralsetinib well, the incidence of adverse reactions was low. Furthermore, pralsetinib is currently approved for RET-mutant non-small cell lung cancer and medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), but selective RET inhibitors also show strong activity in other RET alteration-positive solid tumors. It has been noted that RET fusions are oncogenic in multiple tumors and can be targeted by selective RET inhibition.17 As the patient was nonresponsive to multiple treatment modalities, an NGS revealed a CCDC6-RET gene fusion mutation, for which pralsetinib-targeted therapy was initiated. The patient was evaluated for PR after one cycle of treatment, and the tolerance was good.

The patient underwent only a BRCA germline mutation evaluation before the initiation of systemic therapy. She underwent detailed NGS testing after progressing through multiple lines of therapy, which revealed a RET fusion. Whether the RET fusion was an initial mutation or a secondary drug resistance mutation deserves further investigation. A previous study performed comprehensive molecular analyses on the residual disease of 74 clinically defined TNBC after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC), including NGS on 20 matched pretreatment biopsies.18 As mentioned, the combined NGS and digital RNA expression analysis identified diverse molecular lesions and activation of signal pathways in drug-resistant tumor cells; 90% of the tumors contained a genetic alteration, potentially treatable with currently available targeted therapy. Balko et al detected a higher frequency of several potentially targetable alterations in a cohort of posttreatment TNBC cases compared to basal-like primary breast cancers in the TCGA, including PTEN alterations (PI3K and AKT inhibitors), JAK2 amplifications (ruxolitinib or tofacitinib), CDK6, CCND1, CCND2, CCND3 (CDK4/6 inhibitors), and IGF1R (dalotuzumab).18 Moreover, our case results are in accordance with a few previous studies that revealed that molecular analysis of patients with TNBC who did not achieve a pathological complete response (pCR) after receiving achieving NAC should be performed routinely to stratify patients for rational adjuvant trials with molecularly targeted agents.

Pralsetinib uses a binding mode, quite different from other TKIs.19 The previous research on the complexes with TKIs revealed that the TKIs occupy both the front and back clefts of the drug-binding pockets by passing through the gate area, separating the front and back clefts (eg, vandetanib, PDB code 2IVU; nintedanib, PDB code 6NEC) or bind only to the front cleft, such as alectinib (PDB code 3AOX), certinib (PDB code 4MKC), osimertinib (PDB code 4ZAU), and entrectinib (PDB code 5KVT).20-24 In contrast, pralsetinib docks one end in the front cleft without passing through the gate, wraps around the area outside the gate wall formed by the side chain of K758, and buries the other end in the BP-II pocket of the back cleft.25 Subbiah et al reported that their novel binding mode allowed high-affinity binding while avoiding the disruption of gatekeeper mutations.19 Nevertheless, this novel kinase inhibitor binding mode remains liable to resistance from multiple mutations at several non-gatekeeper residues identified in their study, such as RETG810C/S/N.26 However, Lin et al reported that the majority of resistance to selective RET inhibition might be driven by RET-independent resistance such as acquired MET or KRAS amplification. Henceforth, it is extremely important to continually assess and validate the existing mechanisms of resistance in larger cohorts of RET-altered solid tumors.27

Of course, some limitations may exist in its previous course of treatment due to conditions such as the patient’s performance status (PS) and economic level. First, the results of the KEYNOTE-355 study showed that the median PFS for Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy was significantly prolonged in patients with PD-L1 CPS ≥ 10 (9.7 months) compared to the placebo-combined chemotherapy arm (5.6 months; HR = 0.65, 95% CI, 0.49 to 0.86; P = .0012).28 In this patient, NGS showed that PD-L1 expression was detected in 95% and 95% of TPS and CPS, which may benefit significantly from the immune combination therapy. The patient was advised to combine immunotherapy with second-line therapy, but owing to financial restrictions, the patient declined to combine immunotherapy and signed an informed consent form. The patient developed IV degree myelosuppression when second-line therapy was administered, and the patient was given immunotherapy monotherapy following a thorough assessment of the risks associated with combination therapy, but the patient’s illness advanced rapidly. Second, IMMU-132-01 study found that the patients with metastatic TNBC can benefit significantly from sacituzumab govitecan treatment (ORR = 33%, mPFS = 5.5month, mOS = 13month).29 The patient may benefit from sacituzumab after multiple treatment advances; however, sacituzumab was not approved for TNBC in China by the National Medical Products Administration until June 2022, at this time the patient has started pralsetinib treatment in April 2022 and has shown good benefits. Sacituzumab is the standard of treatment in advanced TNBC patients and may be the next treatment option for patients when conditions allow.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates the excellent therapeutic effect of pralsetinib in targeting RET alteration-positive TNBC and proves that it is a valuable case for the application of selective RET inhibitors in solid tumors other than non-small cell lung and MTCs. Simultaneously, this case also reinforces our understanding that the widespread use and availability of NGS enable personalized targeted treatments for each patient, thus, bringing hope to the field of precision oncology.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient for her participation.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhao, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; College of Clinical Medicine, Shandong First Medical University (Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences), Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Wei Xu, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Xiaoli Zhuo, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; College of Clinical Medicine, Shandong First Medical University (Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences), Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Lei Liu, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; College of Clinical Medicine, Shandong First Medical University (Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences), Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Junlei Zhang, Department of Pathology, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; Department of Pathology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Fengxian Jiang, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; Department of Oncology, The Second Clinical Medical College, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Yanru Shen, Medical Project, Berry Oncology Corporation, Fuzhou, Fujian, People’s Republic of China.

Yan Lei, Berry Oncology Institutes, Berry Oncology Corporation, Fuzhou, Fujian, People’s Republic of China.

Dongsheng Hou, Department of Pathology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Xiaoyan Lin, Department of Pathology, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; Department of Pathology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Cuiyan Wang, Department of Radiology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Guobin Fu, Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China; Department of Oncology, Shandong Provincial Hospital, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, People’s Republic of China.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81802284), Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (No. tsqn202103179), Science and Technology Development Plans of Shandong Province (No. 2014GSF118157), Scientific Research Foundation of Shandong Province of Outstanding Young Scientists (No. BS2013YY058), 2021 Shandong Medical Association Clinical Research Fund (No. YXH2022ZX02176).

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. A written informed consent was provided by the patient to participate.

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: J.Z., W.X., G.F. Provision of study material or patients: X.Z., L.L., J.Z. Data analysis and interpretation: J.Z., W.X., F.J., Y.S., Y.L. Manuscript writing: J.Z., W.X., G.F. Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the SRA database with the accession codes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA874676). The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Gu X, Sun G, Zheng R, et al. Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in People’s Republic of China in 2015. J Natl Cancer Center. 2022;2(2):70-77.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jncc.2022.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mulligan LM. Ret revisited: expanding the oncogenic portfolio. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(3):173-186. 10.1038/nrc3680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Richardson DS, Gujral TS, Peng S, Asa SL, Mulligan LM.. Transcript level modulates the inherent oncogenicity of RET/PTC oncoproteins. Cancer Res. 2009;69(11):4861-4869. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159(3):676-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang R, Hu H, Pan Y, et al. Ret fusions define a unique molecular and clinicopathologic subtype of non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4352-4359. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paratala BS, Chung JH, Williams CB, et al. RET rearrangements are actionable alterations in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4821. 10.1038/s41467-018-07341-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eng C. RET proto-oncogene in the development of human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):380-393. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gainor JF, Curigliano G, Kim DW, et al. Pralsetinib for RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (arrow): a multi-cohort, open-label, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):959-969. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00247-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loibl S, Poortmans P, Morrow M, Denkert C, Curigliano G.. Breast cancer. Lancet. 2021;397(10286):1750-1769. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32381-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Masuda H, Baggerly KA, Wang Y, et al. Differential response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy among 7 triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(19):5533-5540. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gonzalez-Ericsson PI, Stovgaard ES, Sua LF, et al. The path to a better biomarker: application of a risk management framework for the implementation of PD-l1 and TILS as immuno-oncology biomarkers in breast cancer clinical trials and daily practice. J Pathol. 2020;250(5):667-684. 10.1002/path.5406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patrinely JR Jr, Johnson R, Lawless AR, et al. Chronic immune-related adverse events following adjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy for high-risk resected melanoma. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(5):744-748. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):523-533. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gautschi O, Milia J, Filleron T, et al. Targeting RET in patients with RET-rearranged lung cancers: results from the global, multicenter RET registry. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1403-1410. 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.9352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Romei C, Fugazzola L, Puxeddu E, et al. Modifications in the papillary thyroid cancer gene profile over the last 15 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1758-E1765. 10.1210/jc.2012-1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Drilon A, Hu ZI, Lai GGY, Tan DSW.. Targeting ret-driven cancers: lessons from evolving preclinical and clinical landscapes. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(3):151-167. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thein KZ, Velcheti V, Mooers BHM, Wu J, Subbiah V.. Precision therapy for ret-altered cancers with ret inhibitors. Trends Cancer. 2021;7(12):1074-1088. 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Balko JM, Giltnane JM, Wang K, et al. Molecular profiling of the residual disease of triple-negative breast cancers after neoadjuvant chemotherapy identifies actionable therapeutic targets. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(2):232-245. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Subbiah V, Shen T, Terzyan SS, et al. Structural basis of acquired resistance to selpercatinib and pralsetinib mediated by non-gatekeeper RET mutations. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(2):261-268. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Knowles PP, Murray-Rust J, Kjaer S, et al. Structure and chemical inhibition of the RET tyrosine kinase domain. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(44):33577-33587. 10.1074/jbc.M605604200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Terzyan SS, Shen T, Liu X, et al. Structural basis of resistance of mutant RET protein-tyrosine kinase to its inhibitors nintedanib and vandetanib. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(27):10428-10437. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.007682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sakamoto H, Tsukaguchi T, Hiroshima S, et al. Ch5424802, a selective ALK inhibitor capable of blocking the resistant gatekeeper mutant. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(5):679-690. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friboulet L, Li N, Katayama R, et al. The ALK inhibitor ceritinib overcomes crizotinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(6):662-673. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yosaatmadja Y, Silva S, Dickson JM, et al. Binding mode of the breakthrough inhibitor AZD9291 to epidermal growth factor receptor revealed. J Struct Biol. 2015;192(3):539-544. 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Linden OP, Kooistra AJ, Leurs R, de Esch IJP, de Graaf C.. Klifs: a knowledge-based structural database to navigate kinase-ligand interaction space. J Med Chem. 2014;57(2):249-277. 10.1021/jm400378w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin JJ, Liu SV, McCoach CE, et al. Mechanisms of resistance to selective ret tyrosine kinase inhibitors in RET fusion-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(12):1725-1733. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (keynote-355): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10265):1817-1828. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bardia A, Mayer IA, Vahdat LT, et al. Sacituzumab govitecan-HZIY in refractory metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(8):741-751. 10.1056/NEJMoa1814213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the SRA database with the accession codes (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA874676). The derived data generated in this research will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.