Abstract

Background

Glioblastoma (GBM) is a lethal disease. At least in part, the recurrence of GBM is caused by cancer stem cells (CSCs), which are resistant to chemotherapy. Personalized anticancer therapy against CSCs can improve treatment outcomes. We present a prospective cohort study of 40 real-world unmethylated Methyl-guanine-methyl-transferase-promoter GBM patients treated utilizing a CSC chemotherapeutics assay-guided report (ChemoID).

Methods

Eligible patients who underwent surgical resection for recurrent GBM were included in the study. Most effective chemotherapy treatments were chosen based on the ChemoID assay report from a panel of FDA-approved chemotherapies. A retrospective chart review was conducted to determine OS, progression-free survival, and the cost of healthcare costs. The median age of our patient cohort was 53 years (24–76).

Results

Patients treated prospectively with high-response ChemoID-directed therapy, had a median overall survival (OS) of 22.4 months (12.0–38.4) with a log-rank P = .011, compared to patients who could be treated with low-response drugs who had instead an OS of 12.5 months (3.0–27.4 months). Patients with recurrent poor-prognosis GBM treated with high-response therapy had a 63% probability to survive at 12 months, compared to 27% of patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs. We also found that patients treated with high-response drugs on average had an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $48,893 per life-year saved compared to $53,109 of patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs.

Conclusions

The results presented here suggest that the ChemoID Assay can be used to individualize chemotherapy choices to improve poor-prognosis recurrent GBM patient survival and to decrease the healthcare cost that impacts these patients.

Keywords: Cancer stem cells, Cancer Stem Cell Assay, ChemoID, Recurrent Glioblastoma

Key Points.

This study shows that ChemoID-predicted chemotherapies that target cancer stem cells and the bulk of tumor cells improve survival outcomes of GBM patients.

ChemoID is a functional precision medicine assay that improves the quality of care while reducing healthcare costs.

Importance of the Study.

The ChemoID CSC assay improves the outcome of recurrent glioblastoma patients by guiding their chemotherapy treatment and diminishes the cost of healthcare. The ChemoID CSC assay is beneficial in personalizing treatment strategies to increase survival time for recurrent GBM patients and to provide quality metrics for healthcare payers and providers to support access to care.

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most aggressive brain tumor in adults, exhibiting a very poor prognosis with a median time to recurrence of approximately 7 months, and a median survival of 15–18 months even if treated with standard of care (SOC) consisting of maximal surgical resection, and concurrent radiation with Temozolomide and adjuvant treatment with Temozolomide (TMZ).1 Despite this treatment, recurrence is almost inevitable,2 and the prognosis of recurrent GBM remains poor with a median PFS of 5.5 months, and a median OS of 8–9 months.3

Unfortunately, no universally held SOC is available for recurrent GBM, especially those displaying an unmethylated O6-Methyl-guanine-methyl-transferase (MGMT) promoter and wild-type IDH-1/2 gene status. The methylation status of the promoter region of the MGMT gene along with the status of the IDH-1/2 gene have been indicated as the most important negative prognostic predictors of patients’ outcomes.4–7 In these patients, treatment options depend on specific aspects of its presentation, including secondary cytoreductive surgery when possible, focused re-irradiation,8 and numerous second-line chemotherapy treatment options.9 While most patients eventually succumb to the progression of recurrent disease, second-line chemotherapy treatments have provided variable remission and symptom-free survival in a percentage of patients.9 As such, the selection of effective chemotherapy is extremely important for these patients. Additionally, with emerging value-based payment models where outcomes-based contracts link payment for indications of specific cancer drug prices, there are further concerns about the accessibility and affordability of treatments for recurrent GBM patients; therefore, there is a need for effective anticancer drugs that limit overall cost while also increasing treatment value for these patients.

Herein we describe our experience in using ChemoID, a clinical laboratory improvements amendment (CLIA)-certified and College of American Pathologists-accredited clinical diagnostic test that is performed in a clinical-pathology laboratory, which identifies chemotherapeutic agent(s) that kill both the cancer stem cells (CSCs) and the bulk tumor cells, to guide treatment of recurrent GBM.

Methods

Patients

Forty patients (31 males and 9 females), 18 years and older, that were clinically diagnosed with unmethylated MGMT-promoter and IDH-1/2 wild-type recurrent GBM received 2 concurrent biopsies, one that was examined by frozen sectioning for histological diagnosis and another for prospective ChemoID chemotherapeutic testing between January 2017 and February 2020 all at the Allegheny Health Network Hospital in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This chart review of prospectively treated patients was approved by the Allegheny Health Network Institutional Review Board. Under a physician’s order, patients were treated with ChemoID-guided chemotherapy according to their overall functional status and ability to tolerate the recommended treatment. Radiological data was collected before surgery, immediately post-surgery, and following chemo/radiation therapy with an MRI follow-up every 2 months. Supportive care was also allowed at the discretion of the treating physician. Disease status was measured by radiologic examination (MRI scan as the primary imaging method), physical examination, and measurements using the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria,10 which takes into account parameters and evaluations to identify pseudo-progression as well as pseudo-response. Tumor assessments were performed by an independent neuro-radiology service composed of 2 readers and a third senior reader for adjudication of disagreements. All neuro-radiologists were blinded to groups and/or treatment assignments throughout the study to determine the earliest time of progression independent of the impressions of the treating physicians to avoid bias.

ChemoID Assay

Details regarding the CSCs cytotoxicity assay (ChemoID) procedure have been described previously.11–15 In brief, recurrent GBM participants underwent surgical resection of the recurrent tumor and fresh tissue biopsy samples were collected in the operating room under sterile conditions and divided into 2 parts. One part of the biopsy was sent overnight via FedEx clinical pack in a sterile vial containing a transportation medium to the clinical-pathology laboratory at Cabell Huntington Hospital in West Virginia under physician order to perform the ChemoID assay under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified and College of American Pathologists. The second portion of the biopsy was placed in a 10% formaldehyde solution and sent to the local pathology lab for histopathological confirmation. Tissue samples from recurrent GBM-confirmed tumors were also evaluated for methylation of the MGMT gene promoter. Post-surgery/biopsy, patients received a baseline contrast-enhanced brain MRI or CT if MRI was contraindicated.

To generate the primary tumor cell cultures the fresh tumor tissue from surgical biopsies was minced and gently disassociated in a biosafety cabinet. The CSCs were enriched from the primary tumor cell cultures using a 3D-suspension cell culture rotating bioreactor with a volume of 40 mL and a gas-permeable membrane that allows for gas exchange. Culture media, oxygenation, rotation speed, temperature, and CO2 were kept consistently constant in an incubator. The bioreactor can rotate at adjustable speed on a fixed axis creating a 3D-suspension cell culture in the absence of shear forces. Primary cells were counted and 2 × 10^6 cells were cultured in the bioreactor for 7-day set at 25 rpm with airflow set at 20% in RPMI media in the absence of growth factors.12,13,15 Plates (96-well) were seeded with equal numbers of either bulk tumor cells or CSCs and incubated at 37°C. After 24 hours, clinical-grade chemotherapy drugs were added alone or in combination for 1-hour exposure (Table 1). After the 1-hour exposure, the treatment media containing the various chemotherapies were removed and replaced with fresh media. Cell viability was assessed 48 hours later as previously.12,13,15 For each treatment, percent survival (potential therapeutic efficacy) was calculated relative to appropriate controls. Efficacy and resistance of each drug and combinations were reported on the ChemoID assay results as a continuous number from <10% to 100% cell kill.12,13,15

Table 1.

Panel of Chemotherapies Used for Recurrent Glioblastoma and Tested With the ChemoID Assay

| Single Drugs | Dose | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carboplatin | 350 mg/m2 or 4 AUC |

| 2 | Irinotecan | 125 mg/m2 |

| 3 | Etoposide | 50 mg/m2 |

| 4 | BCNU | 100 mg/m2 |

| 5 | CCNU | 100 mg/m2 |

| 6 | Temozolomide | 150-200 mg/m2 |

| 7 | Procarbazine | 60 mg/m2 |

| 8 | Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2 |

| 9 | Imatinib | 400 mg |

|

Drug combinations

|

Dose | |

| 1 | Procarbazine | 60 mg/m2 |

| CCNU | 100 mg/m2 | |

| Vincristine | 1.4 mg/m2 | |

| 2 | Carboplatin | 350 mg/m2 or 4 AUC |

| Irinotecan | 125 mg/m2 | |

| 3 | Carboplatin | 350 mg/m2 or 4 AUC |

| Etoposide | 50 mg/m2 | |

| 4 | Temozolomide | 50 mg/m2 |

| Etoposide | 50 mg/m2 | |

| 5 | Temozolomide | 50 mg/m2 |

| Imatinib | 200 mg |

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were constructed as medians with ranges for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

Two different responder categories were defined: The bulk of tumor responders were those subjects who received a treatment identified by the drug response assay as 55% or above cell kill for the bulk of the tumor and CSC responders were those subjects who received a drug in which the test identified as 40% or above cell kill of CSCs. These cell kill values were derived from previous research and validated in this sample via Youden indices. Summary statistics were calculated where appropriate and all relevant graphs were constructed. Kaplan–Meier graphs were constructed and hazard ratios were calculated. Model assumptions were graphically checked and tested via Schoenfeld residuals and were found to be satisfactory. All statistical analyses were completed using Stata v15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Cost Calculation

The major costs associated with the treatment of recurrent GBM are the cost of the drug response assay, surgery, chemotherapy, adverse events and toxicities, and of end-of-life care. It was assumed that all our patients incurred the same cost per surgery, end-of-life care, and treatment of toxicities; therefore, we did not include these costs in our analysis. For our analysis, we considered only the cost of chemotherapies and the cost of hospitalization due to chemotherapy adverse events. The main source for the cost data in this analysis reflects current Medicare pricing.

Cost of Chemotherapy

All patients in the current model were prospectively treated with a chemotherapy regimen appropriate to their GBM at the time of their recurrence. The costs associated with 6 cycles of each chemotherapy regimen, as well as the associated administration costs (in the physician office setting), were estimated using the current Medicare physician fee schedule for administration payments and drug pricing database for chemotherapy agents.16,17

Cost-Effectiveness and Sensitivity Analysis

The relative cost-effectiveness of the intervention is expressed by the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per life-year saved (ICER/LYS), which is the ratio of the difference in the average costs per patient to the difference in the mean overall survivals. The standard threshold for a healthcare intervention to be deemed cost-effective is an expenditure of between $50,000 and $100,000 per additional year of life saved.18 Keeping the costs for surgery, ChemoID assay, end-of-life care, and adverse event treatment constant between our cohort and historical data, the model results are affected only by the cost of chemotherapies and by survival outcomes. To account for the uncertainty in the hazard ratio estimates associated with the assay and its impact on the ICER/LYS, the range in the ICER/LYS was estimated by 1000 bootstrap samples for the assay. Several stratified analyses for the reference model are also reported. To assess the sensitivity of the model due to the cost of chemotherapy, the scenario when the oncologist chooses the least expensive treatment within the highest category of sensitivity for each patient in the assay-consistent cohort was also investigated.

Results

Overall Cohort Analysis

Fresh tissue samples were collected for ChemoID testing from 40 patients affected by unmethylated-MGMT-promoter GBM, with an overall median age of 53 years (range 24–76), 77% of which were male, all eligible for surgical resection. Recurrence of GBM was confirmed on frozen sections for all patients. The methylation status of the promoter region of the O6-MGMT gene was studied for our entire patient cohort. All patients analyzed in this study had an unmethylated MGMT gene promoter status, indicating they had a negative prognostic predictor of outcome.4–7 The ChemoID assay was performed on all patients using a validated panel of the chemotherapies listed in Table 1. Patients were always treated with the most responsive chemotherapy, as determined by the ChemoID assay, while also taking into account their health status. Table 2 shows the treatments used. Even though the ChemoID test predicted high-response treatments, 11 patients were unable to receive the highest cell-kill treatment because their health status did not allow the use of high-response regimens that the assay predicted. Median age was 53 for low-response CSC drugs versus 51 for high-response drugs. The median time between surgery and the start of chemotherapy treatment was 35 days for the group of patients treated with low-response CSC drugs and 33 days for the high-response treatment group. The median number of cycles was 5 cycles for the group of patients treated with low-response CSC drugs and 6 cycles for the high-response treatment group (P = .277).

Table 2.

Chemotherapy Regiments Used to Treat the Recurrent GBM Cohort

| Low-Response | High-Response | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCNU | 7 | 7 | |

| BCNU/Avastin | 2 | 18 | 20 |

| BCNU/Carboplatin/Avastin | 1 | 1 | |

| BCNU/Imatinib/Avastin | 1 | 1 | |

| BCNU/PCV/Imatinib | 1 | 1 | |

| CCNU and Imatinib | 1 | 1 | |

| Carboplatin | 3 | 3 | |

| Imatinib | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Irinotecan | 1 | 1 | |

| Temodar | 2 | 2 | |

| Temodar, CCNU and Avastin | 1 | 1 | |

| Total | 11 | 29 | 40 |

The overall median KPS status of our patients was 70 (KPS range 60–90). Median KPS was 90 for the group of patients treated with low-response CSC drugs and 80 for the high-response treatment group (P = .059). Median tumor volume at recurrence was 13.6 cm3 for the low-response treatment group and 16.1 cm3 for the high-response treatment group (P = .210). The median amount of steroid prescription for a 24-hour period was 4 mg for the low-response treatment group and 2 mg for the high-response treatment group (P = .640).

Next-generation DNA sequencing was conducted on samples from all patients in our cohort. In 80% of the patients in the low-response treatment group and 82% of the patients in the high-response group, the next-generation DNA sequencing revealed an actionable drug (P = .627).

Survival Analysis

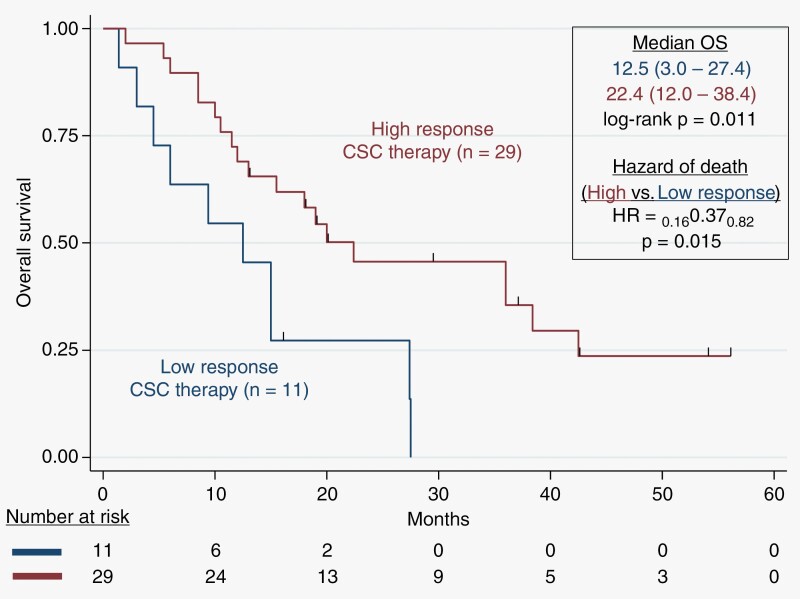

Patients were followed up under the SOC and monitored for overall survival (OS). All patients have been followed up by MRI every 2 months, and the median follow-up from tumor biopsy time was 15.8 months (range 2.0–56.0 months). At the end of our follow-up, 11 patients were still alive. Figure 1 shows the survival times of the recurrent GBM patients prospectively treated using the ChemoID assay results using high-response or low-response chemotherapies.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of overall survival probability. Overall survival (OS) for recurrent GBM patients treated with ChemoID-guided responsive drugs versus low-response drugs. Patients receiving high-response CSC therapy had a median survival of 22.4 months. The Hazard of death was 0.37 (P = .015) based on Kaplan–Meier estimates.

We observed that the median OS of patients treated with high-response CSC therapy was 22.4 months (12.0–38.4) compared to patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs with an OS of 12.5 months (3.0–27.4 months), with a log-rank P = .011. Patients with recurrent GBM treated with high-response therapy had a hazard of death of 0.37 with a 95%CI (0.16–0.82), P = .015, compared to patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs. Notably, of the surviving patients, all have exceeded the expected survivals of previously reported studies.3,19,20

Progression-Free Survival Analysis

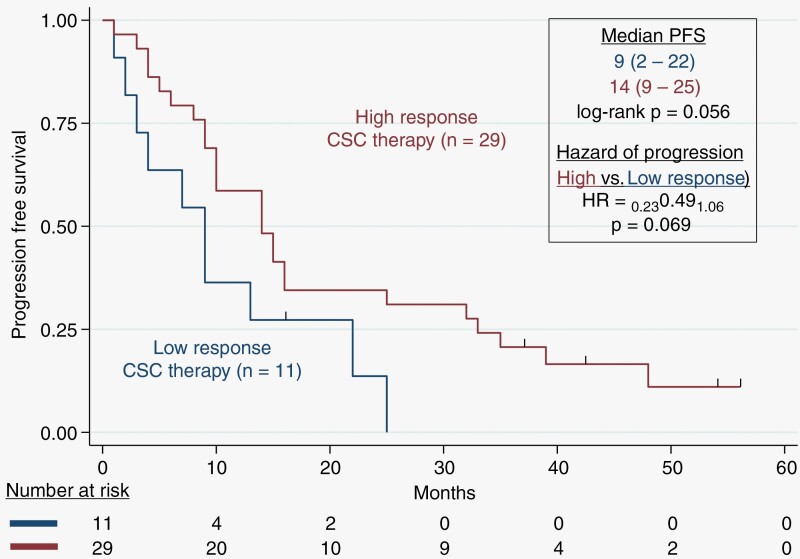

Patients were assessed for progression-free survival (PFS) by the RANO. We observed that the median PFS of patients treated with high-response CSC therapy was 14 months (9.0–25.0 months) compared to patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs with a PFS of 9 months (2.0–22.0 months), with a log-rank P = .056. The median time from original diagnosis to recurrence was 11 months for patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs versus 12 months for high-response drugs (P = .172). Patients with recurrent GBM treated with high-response therapy had a hazard of progression of 0.49 with a 95% CI (0.23–1.06), P = .069, compared to patients who were treated with low-response CSC drugs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plot of progression-free-survival probability. Progression-Free-Survival (PFS) for recurrent GBM patients treated with ChemoID-guided responsive drugs versus low-response drugs. Patients receiving high-response CSC therapy had a median PFS of 14 months. The Hazard of progression was 0.49 (P = .069) based on Kaplan–Meier estimates.

Healthcare Benefit Analysis

To better understand the healthcare benefit and the economic impact of the use of the ChemoID assay, we compared the health benefit observed and the cost of therapies used in our patients’ cohort to the historical data of patients treated empirically with chemotherapies, in a similar manner to previously published investigations.21

The mean cost of therapies administered to GBM patients in the United States alone is $87,810 with a median OS of 18 months, average life years saved of 0.1833, and an ICER/LYS of $84,436 (Table 3). The mean cost of ChemoID-guided high cell kill anti-CSC therapy administered was $99,221 with a median OS of 22.4 months, average life years saved of 0.55, and an ICER/LYS of $48,893. Instead, the mean cost of low cell kill therapy administered was $57,725 with a median OS of 12.5 months, average life years saved of −0.275, and an ICER/LYS of $57,109. The P-value for the difference in ICER/LYS reported in Table 2 is .105, which, despite not being highly statistically significant, still represents cost savings for the patients and their health insurance provider. By comparing the cost from 13 Countries including the EU, and China, we found that the mean cost of therapies administered to GBM patients in the United States is $87,810 with a median OS of 18 months, average life years saved of 0.1417, and an ICER/LYS of $117,984 (Table 4). With a mean cost of ChemoID-guided high cell kill anti-CSC therapy administered was $99,221 with a median OS of 22.4 months, the average life years saved was 0.5083, and the ICER/LYS was $72,037. Instead, the mean cost of low cell kill therapy administered was $57,725 with a median OS of 12.5 months, average life years saved of −0.3167, and an ICER/LYS of $15,401.

Table 3.

Cost of Therapy, Median OS, Average Life Years Saved, and ICER/LYS Comparison of ChemoID-Recommended Versus Not Recommended Drugs in Recurrent GBM in the United States of America

| Overall | Therapy Recommended by ChemoID | Therapy Not Recommended by ChemoID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean cost of therapy | $87,810 | $99,221 | $57,725 |

| Median OS | 18.0 months | 22.4 months | 12.5 months |

| Average life years saved |

0.1833 | 0.55 | −0.275 |

| ICER/LYS* | $84,436 | $48,893 | $53,109 |

*Compared to reported cost and OS for USA in Goel et al. JOURNAL OF MEDICAL ECONOMICS 2021, VOL. 24, NO. 1, 1018–1024. Cost: $72 330. OS: 15.8 months. ICER, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Table 4.

Cost of Therapy, Median OS, Average Life Years Saved, and ICER/LYS Comparison of ChemoID-Recommended Versus Not Recommended Drugs in Recurrent GBM in 13 Countries (Including 12 Countries of the UE and China)

| Overall | Therapy Recommended by ChemoID | Therapy Not Recommended by ChemoID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean cost of therapy | $87,810 | $99,221 | $57,725 |

| Median OS | 18.0 months | 22.4 months | 12.5 months |

| Average life years saved |

0.1417 | 0.5083 | −0.3167 |

| ICER/LYS* | $177,984 | $72,037 | $15,401 |

*Compared to reported cost and OS in Goel et al. JOURNAL OF MEDICAL ECONOMICS 2021, VOL. 24, NO. 1, 1018–1024. Cost: $62 602. OS: 16.3 months. ICER, Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Discussion

Medical management of unmethylated MGMT-promoter recurrent GBM is typically a multimodality treatment plan consisting of maximal safe surgical resection (when possible), followed by radiotherapy with concomitant and maintenance therapy with Temozolomide (TMZ) and/or other secondary chemotherapies,3,22,23 which continually increases treatment morbidity leading to further cost with diminishing returns on the outcome. Moreover, despite aggressive therapy and emerging chemotherapeutic treatment options, because current therapies are still noncurative, the management of these patients remains difficult.

TMZ is a key component of SOC for both newly diagnosed and recurrent GBM patients; however, the major challenge with recurrent GBM treatment is the numerous clinically acceptable and oftentimes equivalent treatment options identified in treatment guidelines.24 Currently, there is insufficient evidence to indicate a superior agent or treatment strategy for recurrent GBM patients as a whole as well as for individual patients.

The presence of CSCs in GBM appears to be responsible, at least in part, for resistance to standard treatments and the variable responses seen to treatment and thus has important implications for the development of a diagnostic assay to guide personalized treatment regimens.25 The current study evaluated the clinical advantage of using the ChemoID chemotherapeutics assay to measure CSC response against a panel of FDA-approved chemotherapies to treat recurrent GBM. Patients were treated with chemotherapies chosen from those drugs showing the highest cell kill as determined by the ChemoID assay, and by taking into consideration the patient’s tolerability to the indicated treatment. Unfortunately, 11 patients could be treated with low-response drugs against CSCs, and their survival and PFS were decreased when compared to those patients who received high-response CSCs therapy.

The vast majority of high-response cell kill was seen in this patient cohort when cells were exposed to BCNU-containing regimens (Table 2). Although only unmethylated MGMT-promoter tumors were present in this population, MGMT is not the only mediator of DNA repair in GBM, especially in response to BCNU (as opposed to TMZ). Future clinical studies that are appropriately designed could look into the use of the ChemoID assay as a bioassay to study various aspects of the mismatch and base excision repair systems as well as other aspects of DNA repair deficiencies in GBM aside from those involved in TMZ detoxifying activity. Additional clinical studies may show that the ChemoID assay can be used to detect variations in the underlying biology of GBMs, and these defects may each be a prognostic factor on their own. Despite the relatively small sample size of the cohort studied, the study revealed that ChemoID, a functional CSC chemotherapeutics assay, can prospectively identify and stratify more effective chemotherapy agents versus other possible choices on an individual patient level for poor-prognosis recurrent GBM patients. In particular, our patient cohort presented with the unfavorable prognostic predictor (unmethylated MGMT promoter),4–6 and we observed that patients who were treated with high-response CSC therapy survived 9.9 months longer in median than those patients who could be only treated with low-response CSC predicted drugs.

Interestingly, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of re-resection and re-irradiation for recurrent GBM indicate that both practices are associated with better overall survival and post-progression survival, providing encouraging disease control and survival rates.26,27 All of the GBM patients in our cohort, received the diagnosis of recurrent disease by histological analysis of a frozen biopsy before providing a sample for the ChemoID assay.

It is known that recurrent GBM is associated with a median overall survival of less than a year and the majority of patients have profound tumor-related symptoms.28,29 Interventions such as re-resection, systemic therapy, and/or re-irradiation may benefit selected patients, but unfortunately, all are given with a palliative intent.29 As such, treatment decisions must be individualized. Clinicians are tasked with selecting the most appropriate treatment, balancing the benefits of treatment with the risk of treatment-related toxicity and its impact on the quality of life.30,31 The performance status of the patient, extent of recurrence (focal versus diffuse), and location of recurrence are important considerations in such instances.30,31

Notably, our cohort of poor-prognosis GBM patients treated with assay-guided therapy had a 63% probability of survival at 12 months, compared to the 27% historical probability of survival at 12 months observed in previous studies,3,19,20 demonstrating the importance of determining CSCs response to chemotherapy to prolong patients’ survival. The data further supports the belief that long-term tumor response in GBM, is in fact, more dependent on the intrinsic sensitivity or resistance of the CSCs to conventional chemotherapies. This concept is especially valuable and important with emerging value-based healthcare models where outcomes-based contracts linked to payment for an indication of specific anticancer-drug prices raise concerns about the accessibility and affordability of treatment for recurrent GBM patients. In the healthcare benefit analysis of this cohort of MGMT unmethylated recurrent GBM patients, the majority of ChemoID assay high-response chemotherapies were observed when cells were exposed to regimens containing BCNU, one of the least expensive drugs on the list of those considered. The analysis would have resulted in a completely different conclusion if, in turn, the most expensive drugs were also found to be the most effective. Nevertheless, our data showed that BCNU-containing regimens, as predicted by the ChemoID assay, were clinically advantageous in this cohort of MGMT unmethylated recurrent GBMs. The power of precision medicine lies in its ability to guide healthcare decisions toward the most effective treatment for a given patient, thereby improving healthcare quality while reducing the need for unnecessary therapies and lowering costs.

ChemoID is a functional precision medicine test that uses a patient’s live bulk of tumor cells and CSCs isolated by tumor biopsies to determine which chemotherapy agent (or “combinations”) is most effective.12 Targeting of CSCs alongside the bulk of other cancer cells is a new paradigm in personalized anticancer treatment. This strategy and technological advancement constitute an important advantage of the ChemoID approach over other diagnostic methods for personalized medicine since individual chemotherapies or their combinations are functionally tested on the patient’s cancer cells and CSCs.

We have also conducted a multi-institutional randomized clinical trial (NCT03632135) and determined the clinical validity of the ChemoID assay as a predictor of clinical response in recurrent GBM.32–35 The study was designed as a parallel-group, controlled clinical trial that randomized participants to either standard-of-care chemotherapy chosen by the physician or ChemoID-guided therapy. In the randomized clinical trial, response to therapy was measured by MRI imaging using RANO criteria to assess overall survival (OS), OS at 6, 9, and 12 months, median PFS, PFS at 4, 6, 9, and 12 months, objective tumor response, time to recurrence, and quality of life. In the randomized study, the recurrent GBM patients treated with ChemoID-guided therapy survived 4.5 months longer in median than those treated with chemotherapies empirically chosen by the physicians.

ChemoID is the first and only chemotherapeutics assay currently available in oncology clinics that examines CSCs susceptibility to conventional FDA-approved drugs from solid tumors. Results from the current real-world study indicate that the ChemoID assay is a valuable and practical tool for optimizing treatment selection when first-line therapy fails, and when there are multiple treatments available. The ChemoID assay takes 2–3 weeks to be completed from the date of receiving a live biopsy, which corresponds to the average time patients spend recovering from surgery before continuing further therapy. Therefore, the ChemoID assay is suitable for timely, individualized chemotherapy for cancer patients who received surgery. Furthermore, our results suggest that this individualized functional chemotherapeutic assay may indeed surpass the results achieved by empiric population-based treatment by providing better treatment options with improved outcomes. This compelling data suggests that the ChemoID CSC assay is beneficial in personalizing treatment strategies to increase survival time for recurrent GBM patients and to provide quality metrics for healthcare payers and providers to support access to care.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the patients and their families who participated in this study. The authors gratefully acknowledge Logan Lawrence, Donna McIlvain, and Veronica Mayes, for technical assistance with the ChemoID assay. We gratefully acknowledge Marshall University and Cabell Huntington Hospital for their support.

Contributor Information

Tulika Ranjan, Department of Neuro-oncology, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; Department of Neuro-Oncology, Cancer Center Southern Florida, and Tampa General Hospital, Tampa, Florida, USA.

Alexander Yu, Department of Neurosurgery, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Shaed Elhamdani, Department of Neuro-oncology, Allegheny Health Network, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA.

Candace M Howard, Department of Radiology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA.

Seth T Lirette, Department of Data Science, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, Mississippi, USA.

Krista L Denning, Department of Anatomy and Pathology, Joan C. Edwards School of Medicine, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia, USA.

Jagan Valluri, Translational Genomics Laboratory, Department of Biological Sciences, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia, USA; Cordgenics, LLC, Huntington, West Virginia, USA.

Pier Paolo Claudio, Department of Pharmacology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Cancer Center and Research Institute, Jackson, Mississippi, USA; Cordgenics, LLC, Huntington, West Virginia, USA.

Funding

The study was funded by Cordgenics, LLC. STL is partially supported by the Mississippi Center for Clinical and Translational Research and Mississippi Center of Excellence in Perinatal Research COBRE funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers 5U54GM115428 and P20GM121334. CMH is partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5U54GM115428. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of interests statement

Drs. Claudio and Valluri own intellectual property rights on the cancer stem cell platform technology licensed to Cordgenics, LLC. No other disclosures were reported for other authors.

Authorship statement

All authors contributed significantly to the present research and reviewed the entire manuscript. TR: Participated in providing patients’ treatment data; also participated substantially in the conception and execution of the study and the analysis and interpretation of data; participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. AY: Participated in providing patients’ samples; also participated substantially in the execution of the study and participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. SE: Participated substantially in the execution of the study and participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. CMH: Analyzed and interpreted the data; also participated substantially in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. STL: Conducted the statistical analysis, participated in the interpretation of data, and the drafting and editing of the manuscript. KD: Participated substantially in providing patients’ ChemoID test results and in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. JV: Participated substantially in the conception and execution of the study and in the drafting and editing of the manuscript. PPC: Participated substantially in the conception and execution of the study and in the drafting and editing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval

This chart review was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at AHN. The ChemoID assay was performed under CLIA following a physician’s order.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy restrictions on medical records but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Johnson DR, O'Neill BP.. Glioblastoma survival in the United States before and during the temozolomide era. J Neurooncol. 2012; 107(2):359–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sundar SJ, Hsieh JK, Manjila S, Lathia JD, Sloan A.. The role of cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Neurosurg Focus. 2014; 37(6):E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Linde ME, Brahm CG, de Witt Hamer PC, et al. Treatment outcome of patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: a retrospective multicenter analysis. J Neurooncol. 2017; 135(1):183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burgenske DM, Yang J, Decker PA, et al. Molecular Profiling of Long-Term IDH-wildtype Glioblastoma Survivors. Neuro Oncol. 2019; 21(11):1458–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao WZ, Guo LM, Xu TQ, Yin YH, Jia F.. Identification of a multidimensional transcriptome signature for survival prediction of postoperative glioblastoma multiforme patients. J Transl Med. 2018; 16(1):368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montano N, D'Alessandris QG, Izzo A, Fernandez E, Pallini R.. Biomarkers for glioblastoma multiforme: status quo. J Clin Transl Res. 2016; 2(1):3–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Binabaj MM, Bahrami A, ShahidSales S, et al. The prognostic value of MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Cell Physiol. 2018; 233(1):378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gigliotti MJ, Hasan S, Karlovits SM, Ranjan T, Wegner RE.. Re-Irradiation with Stereotactic Radiosurgery/Radiotherapy for Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas: Improved Survival in the Modern Era. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2018; 96(5):289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steffens R, Semrau S, Lahmer G, et al. Recurrent glioblastoma: who receives tumor specific treatment and how often? J Neurooncol. 2016; 128(1):85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28(11):1963–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Claudio PP, Valluri J, E Mathis SE, et al. Chemopredictive assay for patients with primary brain tumors. ASCO Annual Meeting. Vol 31, abstr 2089. Chicago2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Howard CM, Valluri J, Alberico A, et al. Analysis of Chemopredictive Assay for Targeting Cancer Stem Cells in Glioblastoma Patients. Transl Oncol. 2017; 10(2):241–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howard CM, Zgheib NB, BushS, 2nd, et al. Clinical relevance of cancer stem cell chemotherapeutic assay for recurrent ovarian cancer. Transl Oncol. 2020; 13(12):100860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mathis SE, Alberico A, Nande R, et al. Chemo-predictive assay for targeting cancer stem-like cells in patients affected by brain tumors. PLoS One. 2014; 9(8):e105710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ranjan T, Howard CM, Yu A, et al. Cancer Stem Cell Chemotherapeutics Assay for Prospective Treatment of Recurrent Glioblastoma and Progressive Anaplastic Glioma: A Single-Institution Case Series. Transl Oncol. 2020; 13(4):100755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. CMS Reimbursement Rates, Part B Drugs. Accessed April 3, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/apps/ama/license.asp?file=https%3A//www.cms.gov/files/zip/april-2020-asp-pricing-file.zip.

- 17. CMS Physician Fee Schedule. Accessed April 5, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.

- 18. Havrilesky LJ, Secord AA, Kulasingam S, Myers E.. Management of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2007; 107(2):211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedman HS, Prados MD, Wen PY, et al. Bevacizumab alone and in combination with irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27(28):4733–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wick W, Gorlia T, Bendszus M, et al. Lomustine and Bevacizumab in Progressive Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377(20):1954–1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plamadeala V, Kelley JL, Chan JK, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of a chemoresponse assay for treatment of patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015; 136(1):94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delgado-Lopez PD, Corrales-Garcia EM.. Survival in glioblastoma: a review on the impact of treatment modalities. Clin Transl Oncol. 2016; 11:1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palmer JD, Bhamidipati D, Song A, et al. Bevacizumab and re-irradiation for recurrent high grade gliomas: does sequence matter? J Neurooncol. 2018; 140(3):623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2019, Anaplastic Gliomas/Glioblastoma (GLIO 1-5). 2019; https://www.nccn.org.

- 25. Parker NR, Hudson AL, Khong P, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity identified at the epigenetic, genetic and transcriptional level in glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:22477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao YH, Wang ZF, Pan ZY, et al. A Meta-Analysis of Survival Outcomes Following Reoperation in Recurrent Glioblastoma: Time to Consider the Timing of Reoperation. Front Neurol. 2019; 10:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kazmi F, Soon YY, Leong YH, Koh WY, Vellayappan B.. Re-irradiation for recurrent glioblastoma (GBM): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurooncol. 2019; 142(1):79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallner KE, Galicich JH, Krol G, Arbit E, Malkin MG.. Patterns of failure following treatment for glioblastoma multiforme and anaplastic astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989; 16(6):1405–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Easaw JC, Mason WP, Perry J, et al. Canadian recommendations for the treatment of recurrent or progressive glioblastoma multiforme. Curr Oncol. 2011; 18(3):e126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krauze AV, Attia A, Braunstein S, et al. Expert consensus on re-irradiation for recurrent glioma. Radiat Oncol. 2017; 12(1):194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krauze AV, Attia A, Braunstein S, et al. Correction to expert consensus on re-irradiation for recurrent glioma. Radiat Oncol. 2018; 13(1):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ranjan T, Sengupta S, Glantz M, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase-3 trial comparing cancer stem cell-targeted vs physician-choice treatments in patients with recurrent high- grade gliomas (NCT03632135). Paper presented at: SNO Annual Meeting; November 16-20, 2022; Tampa, FL.

- 33. Sengupta S, Ranjan T, Glantz M, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase-3 trial comparing cancer stem cell-targeted vs physician-choice treatments in patients with recurrent high- grade gliomas (NCT03632135). Paper presented at: SNO/ASCO CNS Clinical Trial and Brain Metastasis Conference; August 12-14, 2022; Toronto, Canada.

- 34. Sengupta S, Ranjan T, Glantz M, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase-3 trial comparing cancer stem cell-targeted vs physician-choice treatments in patients with recurrent high- grade gliomas (NCT03632135). Paper presented at: AACR Annual Meeting; April 8-13, 2022; New Orleans, LA.

- 35. Ranjan T, Sengupta S, Glantz M, et al. Cancer stem cell assay-guided chemotherapy improves survival in patients with recurrent glioblastoma in a randomized trial. Cell Rep Med. 2023; 4(5):101025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy restrictions on medical records but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.