Abstract

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has not only led to rapid innovation but also shortened the innovation cycle. By comparing the manufacturing and service industries, this study investigated the controversial relationship between product and process innovation from a long-term perspective and examined the synergistic effects of diverse types of innovation on firm performance. Recent five-year Korean Innovation Survey data showed that product and process innovation had interrelationships rather than a one-way sequential relationship. Furthermore, the four different innovation activities have synergistic effects on the firms’ financial performance.

Keywords: Innovation, Interactive and synergistic relationships, Firm performance

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- KIS

Korean Innovation Survey

- OECD

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- VIF

Variance Inflation Factor

- KIS-Value

Korea Information Service Value

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated technology adoption and digital transition, allowing firms to innovate (OECD, 2021). Particularly, the outbreak led to accelerated technological innovation and innovation cycle times, which included significant changes in products, processes, and organizations (Cooper, 2021; Von Krogh et al., 2020). For instance, medical industries have developed and expanded contact-free delivery and pick-up services, whereas manufacturing industries now emphasize personal safety (Rusinko, 2020). Regarding rapid innovation activities, Forbes reported that firms need to rethink innovation processes and products rather than simply shorten their innovation time (Mayer, 2020). Due to the rapid changes in innovation cycle time, the relationships and mechanisms among diverse types of innovations on firm performance have received increasing attention from academics and organizations (Lee et al., 2019).

Recent technological growth has evolved into a service-oriented economy that prioritizes enterprises’ service skills and levels (Coombs and Miles, 2000). In recent years, the service sector has grown significantly and become the dominant contributor to the gross national products of many countries (Lee et al., 2022; Pilawa et al., 2022). Although scholars have examined the sectoral classification of innovation in the service industry, innovation research has traditionally focused on the manufacturing industry (Table 1 ). Unlike the manufacturing industry, the service industry is intangible and has close customer interactions (Ozturk and Ozen, 2021). Research has indicated that the service industry is more likely to focus on existing market strategies and internal sources to attain short-term benefits (incremental product innovation). Conversely, the manufacturing industry is more likely to focus on new market strategies and structures that could lead to radical product innovation (Ettlie and Rosenthal, 2011).

Table 1.

Previous research on innovation among industries.

| Year | Authors | Manufacturing Industry |

Service Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Pilawa et al. | ○ | |

| 2022 | Peixoto et al. | ○ | |

| 2020 | Feng et al. | ○ | |

| 2019 | Lee et al. | ○ | |

| 2016 | Witell et al. | ○ | |

| 2016 | Ferraz and de Melo Santos | ○ | |

| 2015 | Un and Asakawa | ○ | |

| 2012 | Kim et al. | ○ | |

| 2011 | Gunday et al. | ○ | |

| 2011 | Ettlie and Rosenthal | ○ | |

| 2011 | Nasution et al. | ○ | |

| 2010 | Evangelista and Vezzani | ○ | |

| 2004 | Drejer | ○ | |

| 2004 | He and Wong | ○ | |

| 2004 | Pauwels et al. | ○ |

Despite the widespread lack of understanding regarding the link between accelerated product and process innovation and their synergistic impact, research examining the relationship among various types of accelerated innovation activities remains insufficient. For instance, what emerged first: product or process innovation? Do diverse types of innovations have a synergistic effect? Do these relationships differ depending on the industry (manufacturing or services)? Therefore, based on the assumption that product and process innovation share long-term relationships and that an alliance exists among innovation industries, this study investigates the controversial relationship between product and process innovation activities. Additionally, based on the definitions provided in the OECD Oslo Manual (2018), this study examines how different types of innovation affect firm performance. It further compares the effects across manufacturing and service industries. This study empirically examines these relationships using the most recent five-year Korean Innovation Survey (KIS) data for the manufacturing and service industries. It contributes to the innovation literature by investigating the long-term interrelationship between product and process innovation. Moreover, diverse innovation activities have been found to yield a synergistic impact on firm performance, indicating that firms should implement multi-innovation activities simultaneously.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 begins with the theoretical background and hypothesis development. Section 3 presents the methods and results. Section 4 presents the findings of the study and corresponding implications. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper with limitations and directions for future research.

2. Conceptual background and hypothesis development

2.1. Different perspectives between manufacturing and service industries

Previous research perspectives on manufacturing and service industries can be classified into three categories: “assimilation, demarcation, and synthesis” (Witell et al., 2016). Most researchers support the assimilation perspective and assume that new technology drives innovation (Witell et al., 2016). Based on this perspective, manufacturing and service industries adopt the same theories as traditional product innovation research. Moreover, as technology and capital become more important in the service industry, they make it more similar to the manufacturing industry (Witell et al., 2016). Therefore, innovation in the service industry passively accepts innovation from other industries.

However, the demarcation view argues that the manufacturing and service industries are fundamentally different in nature and characteristics (Coombs and Miles, 2000). Proponents of this view posit that different theories should be applied to manufacturing and service innovation (Drejer, 2004). Considering industry characteristics, innovation in the service industry focuses more on customer integration, intangible resources, a firm's internal resources, and non-technological factors (Witell et al., 2016). This perspective expands the concept of innovation beyond traditional innovation research (Drejer, 2004).

The synthesis view argues that firms should consider both technological and non-technological innovations in the manufacturing and service industries (Witell et al., 2016). Based on the Neo-Schumpeterian view, this perspective emphasizes that innovation, which expands previous market solutions, can lead to economic development (Drejer, 2004; Witell et al., 2016). Despite the contributions of each perspective to the innovation research stream, this study concentrates on the synthesis view of innovation in relation to manufacturing and services.

2.2. Innovation types

Diverse perspectives exist on the definition of innovation. Innovation broadly refers to “the acceptance, generation, and implementation of significant new products, routines, services, and ideas” (Thompson, 1962). The OECD Oslo Manual (2018) defines innovation as “a significant or new improvement compared to the previous methods including four types of innovations: product, process, organizational, and marketing innovation.”

Product innovation generally refers to “the introduction or significant improvement of a new product (goods or services), considering its intended uses or attributes” (OECD, 2018). Previous research has categorized product innovation as radical or incremental (Chandy and Tellis, 1998). A new product that is technologically novel and fulfills consumer needs can be regarded as a radical product innovation. In contrast, if the product is low in both technological and customer fulfillment dimensions, it is categorized as an incremental product innovation. Process innovation mainly focuses on significant improvements or new methods of delivery, and supports the managerial process (Rosenberg, 2009). Organizational innovation significantly impacts internal organizational methods, such as business practices and partner relationships (OECD, 2018). It mainly focuses on internal factors like a firm's internal relationships with suppliers and customers. Process innovation focuses more on technological improvements like new software and equipment, whereas organizational innovation focuses on the prime structure of the firm and the people involved flexible work cultures. Marketing innovation refers to “implementing a new or significant modification in the marketing mix: product, pricing, promotion, or placement” (OECD, 2018). Barich and Kotler (1991) have linked marketing innovations with new product success and defined innovation as including new pricing strategies, package design properties, and placement and promotion activities.

2.3. Interrelationship between product and process innovation

Two main research streams focus on the relationship between product and process innovation. Traditionally, the dynamic model suggests a chronological sequential relationship between product and process innovation in three stages: the performance-focused stage (i.e., product innovation), standardization of performance and sales-focused stage (i.e., process innovation), and contraction of the cost stage (Lee et al., 2019). Under this assumption, the relationship follows a chronological sequence of “product then process.” Therefore, radical and incremental product innovation cannot occur simultaneously in identical stages of the dynamic model (Martínez-Ros and Labeaga, 2009).

Recently, many researchers have suggested the opposite direction of “process then product,” indicating that process innovation could simultaneously promote radical and incremental product innovation (Lee et al., 2019). The scholars argue that process innovation increases resource competitiveness and enhances routines. Highly efficient resources lead to product innovation (Kim et al., 2012). With process innovation, firms can conduct shorter and more efficient innovation cycles by identifying available resources and resource fit (Obal et al., 2016). This line of research indicates that abundant resources allow firms to support product innovation.

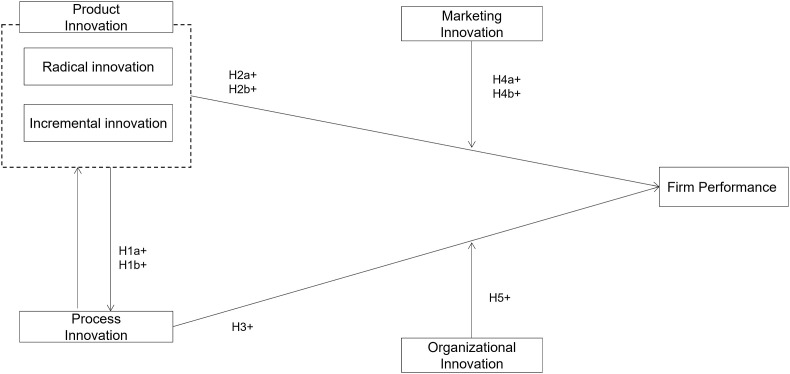

Since innovation activities are cyclical in structure, product and process innovation may affect each other in more than one way; however, their interrelationship remains under-researched. Therefore, this study examines the possible interrelationships between product and process innovation from a long-term perspective (see Fig. 1). Thus,

H1

There is a two-way interrelationship between (a) radical and (b) incremental product innovation and process innovation.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

2.4. Effects of product and process innovation on firm performance

Previous research regards product innovation as a key driver of a firm's financial performance (Lee et al., 2019). For instance, radical product innovation provides entirely new products and greater technology-based consumer benefits (Chandy and Tellis, 1998; Slater et al., 2014). Since radical product innovation is expected to bring high potential profitability (Aboulnasr et al., 2008), it also involves a high level of uncertainty and requires unique and valuable resources with inimitable capabilities for success in the market (Barney, 1991; Teece, 2007). With each unique and differentiated new product, radical product innovation secures product advantages and contributes positively to firm performance (Lee et al., 2019).

Incremental product innovation positively influences firm performance by preventing market failure (Lee et al., 2019). Most companies introduce new products through incremental product innovation (Spanjol et al., 2011); therefore, firm-specific resources and capabilities are crucial. Since implementing incremental product innovation activities is based on a firm's existing experience and resources, firms can effectively reduce costs and time, and increase the speed to market, leading to positive firm performance (Chen et al., 2010). Therefore,

H2

(a) Radical and (b) incremental product innovation positively affect a firm's financial performance.

Process innovation enhances productivity, efficiency, and product quality (Un and Asakawa, 2015). Recently, several researchers have suggested that process innovation activities directly and positively affect firms’ profits (Piening and Salge, 2015) and market share (Dehning et al., 2007). For instance, enhanced routines enable firms to reduce their production costs, allowing them to gain larger profits, thereby aligning with the dynamic capability perspective. Moreover, firms can improve their performance by enhancing their production capabilities (Nair, 2006). Hence,

H3

Process innovation positively affects a firm's financial performance.

2.5. Synergistic effect among innovation activities on firm performance

Marketing innovation is strongly related to product commercialization and is externally focused; thus, it is also strongly related to product innovation (Aarikka-Stenroos and Sandberg, 2012). Even though radical products offer large consumer benefits with new core technologies, significant uncertainties still exist due to increasing market competition (McNally et al., 2010). As stated previously, managing the capabilities of resources is more important than managing superior resources themselves (Teece, 2007). Through consumer and market analyses, marketing innovation helps firms understand the market and develop new relationships with potential consumers (Lee et al., 2019). Thus,

H4

Marketing innovation positively moderates the relationship between (a) radical and (b) incremental product innovation activities and a firm's financial performance.

Organizational innovation offers “valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN)” working practices that allow firms to implement innovations in the process (Camisón and Villar-López, 2014). As organizational innovation is internally focused, it is highly related to process innovation. Moreover, both process and organizational innovation prioritize efficiency and routines (OECD, 2018). Thus, the implementation of process and organizational innovation may establish a more concrete and precise routine. Previous research has also argued that firms can achieve better financial performance by enhancing their routines through internally focused innovation (Un and Asakawa, 2015). Therefore,

H5

Organizational innovation positively moderates the relationship between process innovation and a firm financial performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

The data used in this study were obtained from the most recent five-year dataset of the KIS across the manufacturing and service industries. The KIS is a survey that references the Community Innovation Survey. The KIS questionnaire includes the firm's financial performance, number of full-time employees, implementation of innovation activities, and market strategies. Since the innovation cycle has shortened recently (i.e., 8–14 months), over 3-year data can fully reflect innovation performance. Therefore, the samples were filtered to include firms with complete data for all five years of the KIS. From the manufacturing industries, this study excluded the consumer goods sectors such as food, beverages, and paper products because of their product characteristics. Finally, 312 manufacturing firms were selected to examine the proposed relationships. From the service industry, 416 firms were selected. Since the firms in the dataset were listed or audited, they had a relatively high innovation capacity and prior innovation experience.

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Implementation of innovation

The degree of implementation of innovation activities was measured using a binary scale. Following the OECD Oslo Manual (2018) and Van Beers and Zand (2014), the survey asked respondents about firms' innovativeness and innovation implementation. The items included whether the firms’ product innovation was radical (i.e., “new or first to the market”) or incremental (i.e., “significantly improved”). Additionally, the respondents were asked whether process innovation introduced new processes or significantly improved their business practices. A firm is considered to have implemented process innovation if it includes any of the following activities: new production methods, delivery methods, or supporting managerial processes (OECD, 2018). Regarding marketing innovation activities, the survey asked whether the firm had significantly innovated in the 4Ps of marketing: product design, placement, promotion, and pricing. Organizational innovation activity was recorded by asking whether the firm significantly changed its structure or procedures.

3.2.2. Firm financial performance

Innovation activities are considered to have a time-lagged effect, indicating that their outcomes may be reflected in the following year's performance (Lee et al., 2019). The survey asked respondents to report the total turnover for each year until the sixth year. Although ratio-based accounting measurements, such as return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE), are widely accepted as financial performance indicators, ratio-based indicators may cause biases and unstable results because of confounding correlations between the numerator and denominator (Wiseman, 2009). Recent research suggests using absolute-size measurements to reduce possible bias and accurately capture financial performance, regardless of firm size and variance (Wibbens and Siggelkow, 2020). This study used a natural logarithm of the total turnover one year after the innovation activities as the firm's financial performance.

3.2.3. Control variable

Previous literature indicates that larger firms have better innovation capabilities due to abundant resources, such as in-house R&D (Stoneman, 1995), which aligns with the resource-based view. However, some studies argue that smaller firms have an advantage in implementing innovations in response to market changes and resource modifications (Ettlie and Rosenthal, 2011). Therefore, to control for firm size, this study adopted the natural logarithm of the number of employees (Jansen et al., 2006).

3.3. Data analysis

Owing to the data structure (i.e., binary scale), panel logistic regression with fixed effects estimation was conducted to identify the two-way interrelationship between product and process innovation. A Hausman test was conducted to determine a suitable estimation, which showed no correlation between the independent variables and the error term. Therefore, a fixed-effects estimation was appropriate for the current study (Tong et al., 2008). To examine the interrelationships posited in H1, panel logistic regressions were conducted using the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

This study employed panel regression with a firm fixed-effect estimation to investigate the synergistic effect among various innovation activities on the firm's financial performance (H2-H5). Neither the independent variables nor the error terms exhibited any correlation according to the Hausman test. The model specifications are as follows:

| (5) |

In each equation, denotes the implementation of firm i's innovation activities at time t. The study measured firm performance at t + 1 to reflect the time-lagged effects of innovation.

4. Results

4.1. Manufacturing industries

Table 2 reports the correlations and descriptive statistics. Considering the correlation among variables, the VIFs test was conducted to check potential multicollinearity. All VIF values for the variables were below the recommended cutoff level of 10. The mean VIF value was 1.82, suggesting no concern regarding multicollinearity in the data (Neter et al., 1996).

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptive statistics of the manufacturing industry (N = 312).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Firm Performance | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Radical Product Innovation | 0.126* | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Incremental Product Innovation | 0.147* | 0.486* | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Process Innovation | 0.026 | 0.295* | 0.462* | 1 | |||

| 5 | Organizational Innovation | 0.267* | 0.217* | 0.429* | 0.528* | 1 | ||

| 6 | Marketing Innovation | 0.228* | 0.268* | 0.320* | 0.459* | 0.666* | 1 | |

| 7 | Firm Size | 0.516* | 0.062* | 0.122* | 0.135* | 0.089* | 0.080* | 1 |

| Mean | 9.907 | 0.026 | 0.085 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.053 | 4.572 | |

| SD | 2.258 | 0.16 | 0.279 | 0.275 | 0.271 | 0.223 | 1.096 |

p < 0.05.

The logistic panel regression results reveal that both radical (β = 2.792, p < 0.01) and incremental (β = 3.182, p < 0.01) product innovation simultaneously affect process innovation. Furthermore, process innovation significantly affects radical and incremental product innovation (β = 2.800 and 3.215, respectively, p < 0.01) (Table 3 ). Contrary to previous research, the findings suggest that product and process innovations share a two-way feedback interrelationship rather than a one-way sequential relationship in the manufacturing industry, thus supporting H1a and H1b.

Table 3.

Relationship between product and process innovation in manufacturing industries.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Radical Product Innovation | DV: Incremental Product Innovation | DV: Process Innovation | |

| Radical Product Innovation | . | 2.792*** | |

| (.) | (0.393) | ||

| Incremental Product Innovation | . | 3.182*** | |

| (.) | (0.309) | ||

| Process Innovation | 2.800*** | 3.215*** | . |

| (0.396) | (0.310) | (.) | |

| Firm Size | 0.743 | 0.090 | 0.4812 |

| (0.433) | (0.491) | (0.665) | |

| Observations | 1872 | 1872 | 1872 |

| Number of Firms | 312 | 312 | 312 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

This study estimated five models using panel regression (Table 4 ). All the models were significant at a 0.01 level. Model 8 estimates the effect of innovation activities on a firm financial performance. The results present that each innovation activity positively impacts firm performance ( = 2.326, p < 0.01; = 1.853, p < 0.01; β process = 1.942, p < 0.01; β organizational = 5.332, p < 0.01; β marketing = 1.044, p < 0.10, respectively), supporting H2 and H3. Hence, in manufacturing industries, implementing diverse types of innovation generally helps firms increase their value. The model also confirms the synergistic effects of innovations. Model 8 indicates a positive interaction between radical/incremental product innovation and marketing innovation (β = 1.558, p < 0.05; β = 1.895, p < 0.05, respectively), thus lending support for H4. The results show a positive interaction between process and organizational innovation (β = 2.809, p < 0.01), supporting H5. Firm size has an insignificant effect on any model. Therefore, regardless of size, firms in the manufacturing industry should consider multiple types of innovation activities simultaneously rather than a single type of innovation.

Table 4.

Synergistic effects among innovations in manufacturing industries.

| Variables |

Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Firm financial performance | |||||

| Radical Product Innovation | 1.949** | 2.282*** | 1.891** | 2.604*** | 2.326*** |

| (0.290) | (0.643) | (0.796) | (0.590) | (0.760) | |

| Incremental Product Innovation | 1.625*** | 2.150*** | 2.072*** | 2.171*** | 1.853*** |

| (0.536) | (0.472) | (0.591) | (0.430) | (0.450) | |

| Process Innovation | 1.514** | 1.140*** | 1.349** | 1.856*** | 1.942*** |

| (0.633) | (0.440) | (0.640) | (0.656) | (0.659) | |

| Organizational Innovation | 4.927*** | 5.642*** | 5.332*** | ||

| (0.399) | (0.451) | (0.459) | |||

| Marketing Innovation | 1.732*** | 1.644*** | 1.803* | 1.044* | |

| (0.525) | (0.601) | (0.853) | (0.573) | ||

| Radical Product Innovation * Marketing Innovation |

2.291** | 2.380** | 1.558** | ||

| (1.160) | (1.160) | (0.878) | |||

| Incremental Product Innovation * Marketing Innovation |

2.435** | 1.895** | |||

| (1.085) | (0.739) | ||||

| Process Innovation * Organizational Innovation |

2.579*** | 2.809*** | |||

| (0.893) | (0.910) | ||||

| Firm Size | −0.615 | −0.455 | −0.595 | −0.174 | −0.118 |

| (0.556) | (0.553) | (0.555) | (0.527) | (0.527) | |

| Observations | 1560 | 1560 | 1560 | 1560 | 1560 |

| Number of Firms | 312 | 312 | 312 | 312 | 312 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4.1.1. Robustness check

To check the robustness of the results, the study conducted additional analyses of the synergistic effects among the innovations. For this purpose, the study replicates the estimates in Models 4–7. Model 4 tests how innovation activities affect a firm's financial performance. The findings show that each innovation activity positively affects a firm's financial performance (p < 0.05), being consistent with the results presented. Models 5–7 illustrate the synergistic effects among the innovations. These findings are in line with the initial results, suggesting positive interactions between radical/incremental product and marketing innovation (β = 2.380, p < 0.05; β = 2.435, p < 0.05, respectively), and process and organizational innovation (β = 2.579, p < 0.01) (Table 4).

4.2. Service industries

Table 5 reports the correlations and descriptive statistics among variables. The correlations exhibit low and acceptable values. To check for multicollinearity, VIFs were tested for the variables, which were all below the recommended cutoff level of 10. The mean VIF value was 1.47, suggesting no concern regarding multicollinearity (Neter et al., 1996).

Table 5.

Correlations and descriptive statistics in the service industry (N = 416).

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Firm Performance | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | Radical Product Innovation | −0.019 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Incremental Product Innovation | 0.054* | 0.269* | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Process Innovation | 0.146* | 0.192* | 0.428* | 1 | |||

| 5 | Organizational Innovation | 0.173* | 0.164* | 0.188* | 0.433* | 1 | ||

| 6 | Marketing Innovation | 0.145* | 0.143* | 0.362* | 0.388* | 0.414* | 1 | |

| 7 | Firm Size | 0.727* | −0.018 | 0.022 | 0.109* | 0.141* | 0.087* | 1 |

| Mean | 8.586 | 0.005 | 0.242 | 0.032 | 0.484 | 0.057 | 3.936 | |

| SD | 1.457 | 0.728 | 0.154 | 0.175 | 0.215 | 0.231 | 1.369 |

p < 0.05.

The logistic panel regression results for the service industry presented in Table 6 indicate that only incremental product innovation significantly influences process innovation (β = 2.263, p < 0.01) in service industries. Additionally, process innovation significantly affects incremental product innovation (β = 2.296, p < 0.01), supporting H1b and rejecting H1a. These results show that, regardless of firm size, service firms may pursue relatively short-term goals and lean processes compared to manufacturing firms (Wies et al., 2023).

Table 6.

Relationship between product and process innovation in service industries.

| Variables | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Radical Product Innovation | DV: Incremental Product Innovation | DV: Process Innovation | |

| Radical Product Innovation | . | 0.753 | |

| (.) | (0.721) | ||

| Incremental Product Innovation | . | 2.263*** | |

| (.) | (0.608) | ||

| Process Innovation | 0.702 | 2.296*** | . |

| (0.712) | (0.612) | (.) | |

| Firm Size | −0.031 | 0.231 | −0.197 |

| (0.267) | (0.299) | (0.420) | |

| Observations | 2496 | 2496 | 2496 |

| Number of Firms | 416 | 416 | 416 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

This study estimates five models using panel regressions (Table 7 ). Model 8 provides coefficient estimates for the effect of each innovation activity on a firm's financial performance. Model 8 demonstrates that all innovation activities, except radical product innovation positively influence firms' financial performance (p < 0.05), supporting H2b and rejecting H2a. Radical product innovation does not significantly interact with marketing innovation (β = 0.008, n.s.), whereas incremental product innovation significantly interacts with marketing innovation (β = 0.079, p < 0.05), supporting H4b and rejecting H4a. Moreover, Model 8 indicates a significant interaction between process and organizational innovation (β = 0.081, p < 0.05), supporting H5. Unlike in manufacturing industries, firm size significantly affects other variables in service industries. These results imply that firms in the service industry are less likely to implement radical product innovation which increases uncertainty and risk. Therefore, firms in service industries should focus on implementing multiple innovation activities simultaneously, similar to manufacturing industries.

Table 7.

Synergistic effects among innovations in service industries.

| Variables DV: Firm financial performance | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical Product Innovation | −0.026 | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.026 | −0.020 |

| (0.050) | (0.057) | (0.050) | (0.050) | (0.057) | |

| Incremental Product Innovation | 0.074*** | 0.045** | 0.059** | 0.070*** | 0.053** |

| (0.024) | (0.025) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.023) | |

| Process Innovation | 0.053** | 0.102*** | 0.069*** | 0.062*** | 0.086*** |

| (0.023) | (0.022) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |

| Organizational Innovation | 0.069*** | 0.048** | 0.040** | ||

| (0.017) | (0.021) | (0.019) | |||

| Marketing Innovation | 0.036** | 0.054*** | 0.036** | 0.033** | 0.032** |

| (0.017) | (0.015) | (0.019) | (0.017) | (0.018) | |

| Radical Product Innovation * Marketing Innovation |

0.097 | 0.127 | 0.008 | ||

| (0.109) | (0.095) | (0.110) | |||

| Incremental Product Innovation * Marketing Innovation |

0.061** | 0.079** | |||

| (0.035) | (0.033) | ||||

| Process Innovation * Organizational Innovation |

0.986** | 0.081** | |||

| (0.048) | (0.028) | ||||

| Firm Size | 0.017** | 0.016** | 0.014** | 0.008** | 0.008** |

| (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Observations | 1656 | 1656 | 1656 | 1656 | 1656 |

| Number of Firms | 416 | 416 | 416 | 416 | 416 |

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

4.2.1. Robustness check

Several robustness checks were performed to explore the synergistic effect of innovations in the service industries. All innovation activities except radical product innovation, positively affect a firm's financial performance (p < 0.05), consistent with the results presented. Throughout Models 5–7, the findings reveal consistent results suggesting that radical product innovation has insignificant interaction with marketing innovation (β = 0.127, n.s.), incremental product innovation significantly interacts with marketing innovation (β = 0.061, p < 0.05), and process innovation significantly interacts with organizational innovation (β = 0.986, p < 0.05).

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1. Theoretical and managerial implications

This study contributes to both academia and the industry. Previous innovation research has mainly focused on the sequential relationship between product and process innovation and one or two types of innovation simultaneously. To gain a holistic understanding of innovation, this study examines the interrelationship between product and process innovation in relation to the interdependency among the four types of innovation.

Previous research has suggested a one-way sequential relationship between these two innovation activities (Lee et al., 2019). However, the findings of this study reveal a two-way interrelationship between product and process innovation activities across the manufacturing and service industries. In the manufacturing industry, both radical and incremental product innovation are interrelated with process innovation, whereas in the service industry, only incremental product innovation has a two-way interrelationship with process innovation. Although radical product innovation does not share an interrelationship with process innovation, it does not align with the previous research perspective of a one-way sequential relationship. Thus, the current findings posit that product and process innovation can occur simultaneously and affect each other, rather than sharing a one-way sequential relationship, contradicting previous research.

Research has shown that both radical and incremental product innovation interact strongly with marketing innovation, and process innovation interacts strongly with organizational innovation, leading to higher performance, especially in high-tech manufacturing industries (Camisón and Villar-López, 2014; Lee et al., 2019). However, the current findings indicate that, in both industries, organizational innovation is more effective in enhancing firm performance when implemented with process innovation. In manufacturing industries, marketing innovation is more effective in enhancing firm value when implemented with both radical and incremental innovation, whereas in service industries, it only interacts with incremental product innovation. These findings show that different types of innovation activities complement each other. A firm's ability to manage or implement non-technological innovation is also important for achieving better technological innovation. Therefore, to achieve better performance, firms should consider multiple innovation activities simultaneously rather than a single type.

5.2. Limitations

Although the current study suggests an approach toward investigating the interrelationship between product and process innovation and the synergistic effects among the four different types of innovation, several limitations should be addressed. First, although the study attempted to aggregate panel data, the number of years and amount of data were relatively limited. The KIS survey conducted before 2016 made it difficult to set up panel data because the items and scales of each survey were inconsistent. After 2016, the KIS applied the same measurement items to all firms. Thus, it may be possible to construct a panel dataset for future surveys. Second, this study measured firms' financial performance based on innovation activities. Future research should address non-financial performance, such as the satisfaction of internal and external customers or how the market perceives innovation activities. Finally, since the dataset was archived, it was challenging to identify the in-depth underlying mechanisms of innovation activities. Although the current study cross-verified the data with objective firm financial data from KIS-Value (from the NICE Information Service) to present robust results, it could not empirically measure the firm's strategic combination of innovation activities like the conditions determining a firm's focus on the type of innovation activity. Thus, future researchers should explore the mechanisms that influence firms to combine innovation activities under certain conditions.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Jeongbin Whang is a Ph.D. Candidate in Marketing at the Korea University Business School in Seoul, South Korea. He is interested in innovation including high-tech marketing and ESG studies. He has published in the Journal of Business Research.

Woojung Chang is a Professor of Marketing at the University of Seoul. Her research interests lie in relationship marketing with an emphasis on customer participation in new product development, B2B marketing, and customer relationship management. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Marketing, Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, and Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services among others.

Jong-Ho Lee is a Professor of Marketing at the Korea University Business School in Seoul, South Korea. He has published in the Journal of Business Research, Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Product Innovation Management, European Management Journal, Marketing Letters, International Journal of Advertising, and MIT Sloan Management Review.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Korea University Business School Research Grant.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aarikka-Stenroos L., Sandberg B. From new-product development to commercialization through networks. J. Bus. Res. 2012;65:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Aboulnasr K., Narasimhan O., Blair E., Chandy R. Competitive response to radical product innovations. J. Market. 2008;72:94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Barich H., Kotler P. A framework for marketing image management. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991;32:94–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991;17:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Camisón C., Villar-López A. Organizational innovation as an enabler of technological innovation capabilities and firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014;67:2891–2902. [Google Scholar]

- Chandy R.K., Tellis G.J. Organizing for radical product innovation: the overlooked role of willingness to cannibalize. J. Mar. Res. 1998;35:474–487. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Damanpour F., Reilly R.R. Understanding antecedents of new product development speed: a meta-analysis. J. Oper. Manag. 2010;28:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs R., Miles I. Innovation Systems in the Service Economy. Springer; 2000. Innovation, measurement and services: the new problematique; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper R.G. Accelerating innovation: some lessons from the pandemic. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2021;38:221–232. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehning B., Richardson V.J., Zmud R.W. The financial performance effects of IT-based supply chain management systems in manufacturing firms. J. Oper. Manag. 2007;25:806–824. [Google Scholar]

- Drejer I. Identifying innovation in surveys of services: a Schumpeterian perspective. Res. Pol. 2004;33:551–562. [Google Scholar]

- Ettlie J.E., Rosenthal S.R. Service versus manufacturing innovation. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2011;28:285–299. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J.J., Van Den Bosch F.A., Volberda H.W. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Manag. Sci. 2006;52:1661–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-Y., Kumar V., Kumar U. Relationship between quality management practices and innovation. J. Oper. Manag. 2012;30:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R., Lee J.-H., Garrett T.C. Synergy effects of innovation on firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019;99:507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lee W.-L., Liu C.-H., Tseng T.-W. The multiple effects of service innovation and quality on transitional and electronic word-of-mouth in predicting customer behaviour. J. Retailing Con. Serv. 2022;64 [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Ros E., Labeaga J.M. Product and process innovation: persistence and complementarities. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2009;6:64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer H.M. Innovation due to covid: yes, but how? Forbes. 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hannahmayer/2020/08/26/innovation-due-to-covid-yes-but-how/?sh=7a40a4f34b7e

- McNally R.C., Cavusgil E., Calantone R.J. Product innovativeness dimensions and their relationships with product advantage, product financial performance, and project protocol. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2010;27:991–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Nair A. Meta-analysis of the relationship between quality management practices and firm performance—implications for quality management theory development. J. Oper. Manag. 2006;24:948–975. [Google Scholar]

- Neter J., Kutner M.H., Nachtsheim C.J., Wasserman W. 1996. Applied Linear Statistical Models. [Google Scholar]

- Obal M., Kannan-Narasimhan R., Ko G. Whom should we talk to? Investigating the varying roles of internal and external relationship quality on radical and incremental innovation performance. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2016;33:136–147. [Google Scholar]

- OECD Oslo manual 2018. 2018. [DOI]

- OECD COVID-19 crisis: a fast-track path towards more innovation and entrepreneurship? 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/706b5701-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/706b5701-en#abstract-d1e14029

- Ozturk E., Ozen O. How management innovation affects product and process innovation in Turkey: the moderating role of industry and firm size. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2021;18:293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Piening E.P., Salge T.O. Understanding the antecedents, contingencies, and performance implications of process innovation: a dynamic capabilities perspective. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2015;32:80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pilawa J., Witell L., Valtakoski A., Kristensson P. Service innovativeness in retailing: increasing the relative attractiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retailing Con. Serv. 2022;67 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg N. World Scientific; 2009. Studies on Science and the Innovation Process: Selected Works by Nathan Rosenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Rusinko C. IT responses to Covid-19: rapid innovation and strategic resilience in healthcare. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020;37:332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Slater S.F., Mohr J.J., Sengupta S. Radical product innovation capability: literature review, synthesis, and illustrative research propositions. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2014;31:552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Spanjol J., Tam L., Qualls W.J., Bohlmann J.D. New product team decision making: regulatory focus effects on number, type, and timing decisions. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2011;28:623–640. [Google Scholar]

- Stoneman P. Blackwell; 1995. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation and Technological Change. [Google Scholar]

- Teece D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007;28:1319–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson W.R. The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors. Princeton University Press; 1962. Locational differences in inventive effort and their determinants; pp. 253–272. [Google Scholar]

- Tong T.W., Reuer J.J., Peng M.W. International joint ventures and the value of growth options. Acad. Manag. J. 2008;51:1014–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Un C.A., Asakawa K. Types of R&D collaborations and process innovation: the benefit of collaborating upstream in the knowledge chain. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2015;32:138–153. [Google Scholar]

- Van Beers C., Zand F. R&D cooperation, partner diversity, and innovation performance: an empirical analysis. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2014;31:292–312. [Google Scholar]

- Von Krogh G., Kucukkeles B., Ben-Menahem S.M. Lessons in rapid innovation from the COVID-19 pandemic. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020;61:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wibbens P.D., Siggelkow N. Introducing LIVA to measure long‐term firm performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2020;41:867–890. [Google Scholar]

- Wies S., Moorman C., Chandy R.K. Innovation imprinting: why some firms beat the post-ipo innovation slump. J. Market. 2023;87(2):232–252. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman R.M. Research Methodology in Strategy and Management. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2009. On the use and misuse of ratios in strategic management research. [Google Scholar]

- Witell L., Snyder H., Gustafsson A., Fombelle P., Kristensson P. Defining service innovation: a review and synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69:2863–2872. [Google Scholar]

References

- Evangelista R., Vezzani A. The economic impact of technological and organizational innovations. A firm-level analysis. Res. Pol. 2010;39:1253–1263. [Google Scholar]

- Feng C., Ma R., Jiang L. The impact of service innovation on firm performance: a meta-analysis. J. Serv. Manag. 2020;32:289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz I.N., de Melo Santos N. The relationship between service innovation and performance: a bibliometric analysis and research agenda proposal. RAI Rev. Admin. Inov. 2016;13:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gunday G., Ulusoy G., Kilic K., Alpkan L. Effects of innovation types on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011;133:662–676. [Google Scholar]

- Nasution H.N., Mavondo F.T., Matanda M.J., Ndubisi N.O. Entrepreneurship: its relationship with market orientation and learning orientation and as antecedents to innovation and customer value. Ind. Market. Manag. 2011;40:336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels K., Currim I., Dekimpe M.G., Hanssens D.M., Mizik N., Ghysels E., Naik P. Modeling marketing dynamics by time series econometrics. Market. Lett. 2004;15:167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Peixoto M.R., de Oliveira Paula F., da Silva J.F. Factors that influence service innovation: a systematic approach and a categorization proposal. Eur. J. Innovat. Manag. 2022 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.