Abstract

Background

Early initiation of breastfeeding is important for establishing continued breastfeeding. However, previous research report that cesarean section (C-section) may hinder early initiation of breastfeeding. Despite this, there is currently a lack of literature that examines the rates of breastfeeding after both cesarean section and vaginal birth globally.

Research aims

The objective of this scoping review was to systematically assess the available literature on the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding within the first hour and exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months after C-section and vaginal birth, as well as any other factors associated with initiation and exclusive breastfeeding.

Methods

We adhered to the PRISMA extension guidelines for scoping reviews in conducting our review. In August 2022, we carried out an electronic database search on CINALH, PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, and also manually searched the reference list.

Results

A total of 55 articles were included in the scoping review. The majority of these studies found that mothers who delivered vaginally had higher rates of breastfeeding compared to those who underwent a C-section, at various time points such as breastfeeding initiation, hospital discharge, one month, three months, and six months postpartum. Notably, there was a significant difference in the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding between the two groups. However, at 3 and 6 months after delivery the gap of exclusive breastfeeding rate between C-section and vaginal delivery is narrow. Breastfeeding education, health care providers support, and mother and baby bonding are other factors associate with initiation and exclusive breastfeeding.

Conclusions

The rate of breastfeeding initiation after C-section has remained low to date. This is due in part to insufficient knowledge about and support for breastfeeding from healthcare providers.

Keywords: Breast feeding, Cesarean section, Lactation, Postpartum period, Vaginal birth

1. Background

Breastfeeding is widely recognized as the optimal source of nutrition for infants, providing numerous health benefits and reducing the risk of infant morbidity. In addition to its health benefits, breastfeeding is also cost-effective and easy to implement [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends initiating breastfeeding within the first hour of life to prevent neonatal deaths caused by infections such as sepsis, pneumonia, and diarrhea. Furthermore, exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life helps protect against gastrointestinal problems and allergies [1]. Studies have shown that if babies are breastfed within the first hour of life, it can reduce the risk of neonatal death by 15% [2]. However, globally, only 57.6% of newborns are breastfed within the first hour after birth, falling short of the WHO target [2].

The mode of delivery has a considerable association with breastfeeding practices, with C-section delivery being reported to have negative effect on early initiation of breastfeeding [3]. A population-based study conducted in Ethiopia reported that women who underwent a C-section were 86% less likely to initiate breastfeeding early [4]. Similarly, a cohort study conducted in Italy by Zanardo et al. reported that only 3.5% of mothers breastfed their babies within 1 h after a C-section [5].

A cesarean section (C-section or CS) is an invasive birth procedure that involves making incisions in the abdomen and uterus to deliver a baby when vaginal birth (VB) is deemed high-risk for the mother or baby's safety [6]. The global rate of C-sections has been increasing and has exceeded the World Health Organization's recommended range of 5–15% [7]. One of the reasons for the rising number of C-sections is maternal request, as reported by Chien (2021) and Jenabi et al. (2020) [7,8].

C- section may be necessary for saving lives, however performing them unnecessarily has been associated with increased maternal and infant morbidity as well as higher maternal mortality [9]. Additionally, C-sections have been associated with increased complications in subsequent births and breastfeeding experiences [7]. Studies have consistently shown that women who have undergone a C-section are less likely to initiate breastfeeding and tend to delay the process, which can negatively impact their chances of continued breastfeeding [3,10,11].

Monitoring the progress on breastfeeding practice will promote global strategy and action for infant feeding, and it can serve as a useful point of reference for healthcare providers, policymakers, and other stakeholders in promoting and supporting breastfeeding practices. However, to our knowledge, there has not been a scoping review examining the rate of breastfeeding from early initiation up to 6 months following both C-section and vaginal birth.

2. Aims

The aim of this scoping review is to conduct a thorough and systematic evaluation of the existing literature regarding the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding for up to six months following both C-section and vaginal birth. The review also aims to identify any other factors that may be associated with initiation and exclusive breastfeeding.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

This scoping review followed the methodological framework of the Joanna Briggs Institutes (JBI) of 2017 and adhered to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The JBI framework involved identifying pertinent studies aligned with the research aims, selecting eligible studies, charting the data, summarizing the findings, and reporting the outcomes [12].

3.2. Eligibility criteria

This study adheres to the PCC (Population, Concept, and Context) framework for setting inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion for this study were:

-

1.

Original studies (primary or secondary data analysis)

-

2.

Studies that reported the rate of initiation and exclusive breastfeeding both VB and CS groups in the same cohort

-

3.

English

-

4.

In or after 1990

-

5.

Full text

-

6.

High or moderate quality based on critical appraisal.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

1.

Editorials, letters, commentaries, opinion papers, grey literature studies, conference, trial registration, reviews, not peer review articles

-

2.

Studies that reported the rate of initiation and exclusive breastfeeding only in VB or CS

-

3.

Non-English

-

4.

Before 1990

-

5.

Non-full text

-

6.

Poor quality based on critical appraisal.

3.3. Search strategy and information sources

In August 2022, we conducted an electronic search of several databases, including Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINALH), PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library, to find relevant literature on breastfeeding and C-section. We also manually searched the references. The search utilized Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms related to these topics. The full search strategy is “breast feeding" [MeSH Terms] OR breast feeding [Text Word] OR “milk, human" [MeSH Terms] OR breast milk [Text Word] OR “lactation" [MeSH Terms] OR lactation [Text Word] AND “cesarean section" [MeSH Terms] OR cesarean section [Text Word] OR caesarean section [Text Word] OR caesarean delivery [Text Word] OR caesarean birth [Text Word] OR c-section [Text Word].

3.4. Selection of studies

After the search, RefWorks was used to remove any duplicate search results. The search results were then transferred to Rayyan application, which facilitated the screening process [13]. The lead researcher independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria were then independently assessed. Although quality appraisal is not mandatory in scoping reviews, we employed the JBI framework for cross-sectional and cohort studies to thoroughly screen the studies included and eliminate poor-quality studies. Three researchers critically assessed the included studies, categorizing their quality scores into three groups: high quality (total score >70%), moderate quality (total score 40%–70%), and poor quality (total score <40%). The articles were scored independently by the three researchers, and their scores were subsequently compared and discussed.

3.5. Data charting

The lead researcher extracted the data and confirmed by the other researchers. The data extracted from the studies included [1]: author(s), [2], year of publication, [3], country, [4], study design, [5], population, [6], Breastfeeding rate (%) [7] other factors associated with breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding, [8], notable findings and [9] quality appraisal.

3.5.1. Operational definitions

Vaginal birth in this study includes both spontaneous vaginal birth and using vacuum or forceps birth.

C-section combined across the c-section with planned and emergency C-section.

Early initiation of breastfeeding

If the mothers begun to breastfeed her infant within 1 h of birth with C-section or vaginal birth (based on WHO definition).

Late initiation of breastfeeding

If the mothers begun to breastfeed her infant after 1 h of birth with C-section or Vaginal birth.

Exclusive breastfeeding

Full breastfeeding or the infant was fed only breast milk without any other intake except for medications and vitamins.

4. Results

4.1. Selection of sources

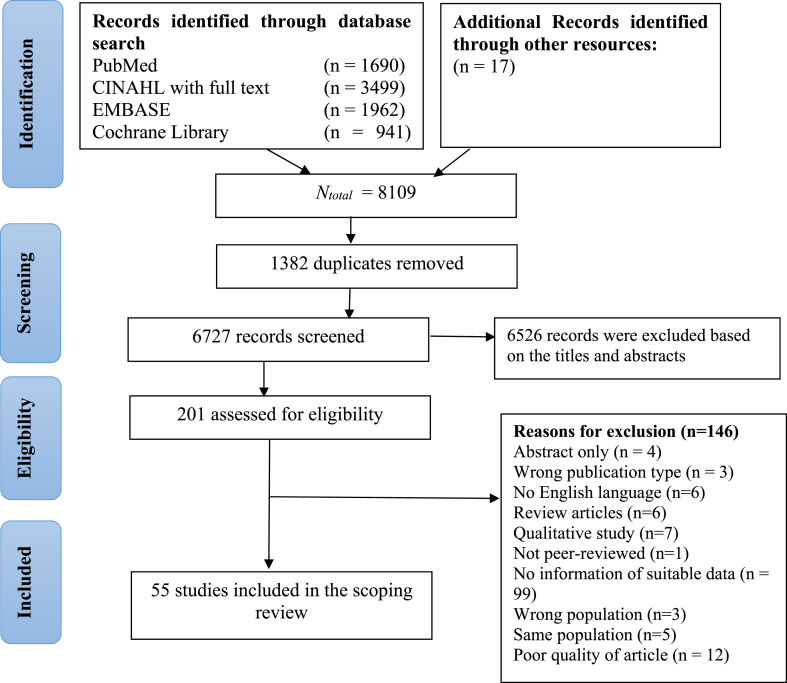

During the database search, 8109 articles were identified as potentially relevant. After removing 1382 duplicate articles, 6727 articles were screened based on their titles and abstracts, and 6526 of them were excluded. The remaining 201 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 146 articles that did not meet the criteria were removed after full-text screening. Ultimately, 55 articles published from 1999 to 2022 were included in the scoping review. Of these, 36 were cross-sectional studies, and 19 were cohort studies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

4.2. Study characteristics

The studies were conducted in the following continents: 22 studies from Asia, 16 studies from Africa, 10 studies from North America, 5 studies from Europe, 1 study from South America and 1 study Australia/Oceania.

This study aimed to examine the percentage of breastfeeding among mothers who underwent C-section or VB. A total of 34 studies were included in the analysis, which focused on the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding, while 11 studies focused on the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge (during hospital stay that lasts for 2–5 days). Additionally, the analysis involved 7 studies on exclusive breastfeeding one month after birth, 8 studies on exclusive breastfeeding three months after birth, and 12 studies on exclusive breastfeeding six months after birth.

4.3. Synthesis of results

Appendix 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of the included studies. The results indicate that mothers who had vaginal birth tend to have higher rates of breastfeeding initiation compared to those who had C-section. Additionally, most studies suggest that successful early initiation of breastfeeding is associated to exclusive breastfeeding at one and three months. However, caution is advised when interpreting the association between early initiation of breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding at six months.

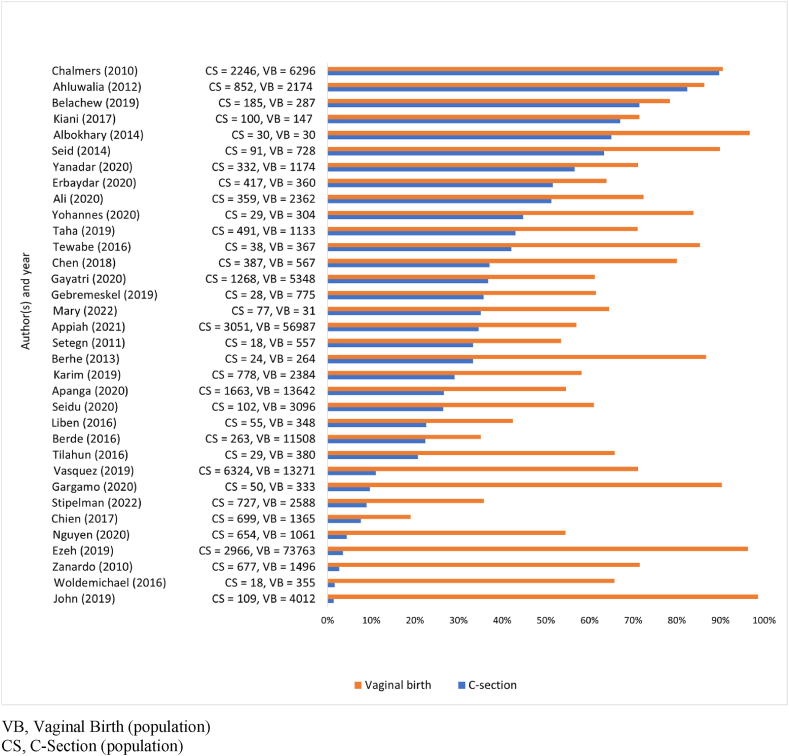

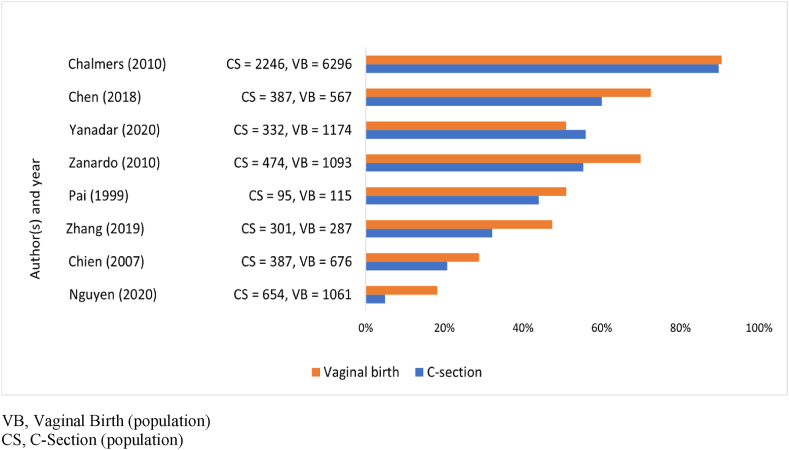

Fig. 2 shows that the rates of early breastfeeding initiation were higher in the mothers who had a vaginal birth than in those who had a C-section. Of total 34 studies in early initiation of breastfeeding, 22 studies reported the rate of early initiation of breastfeeding in mothers who had CS were below 40%. Of these 22 studies, 8 studies showed the rate was below 10%.

Fig. 2.

Percentages of early initiation of breastfeeding (≤1 h).

Most studies show a large difference in the percentages of initiation of breastfeeding between VB and C-section, and only 3 articles by Chalmers et al. (2010), Ahluwalia et al. (2012) and Kiani et al. (2017) showed almost the same percentage of early initiation of breastfeeding between mothers who had CS and VB [[14], [15], [16]]. Chalmers et al. (2010) explained that mostly mother get regional anesthesia for cesarean sections in Canada which possible for them to skin-to-skin contact with their baby immediately after birth [14]. In addition, Kiani et al. (2017) describe the successful of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nicaragua because implemented the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) practice such as skin‐to‐skin contact and other practices [16].

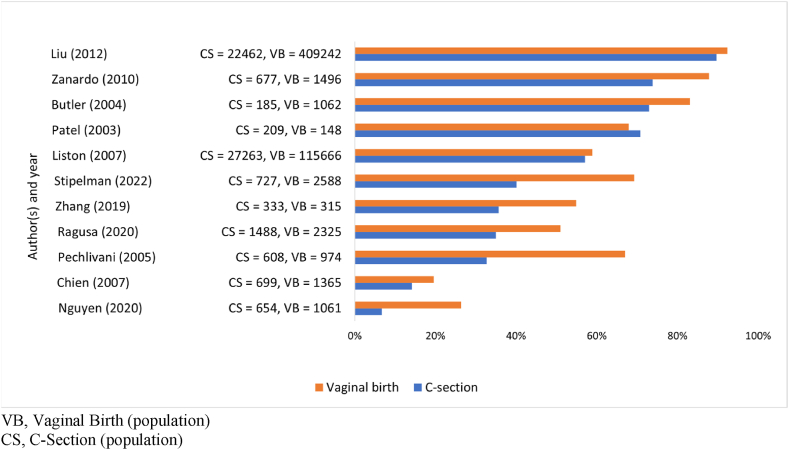

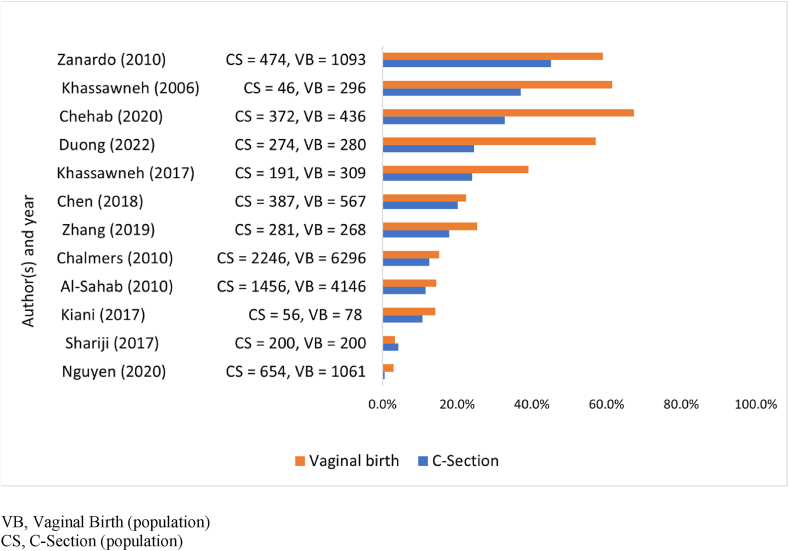

As for percentages of exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge (Fig. 3) showed that the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in the mothers who had C-Section were more than 50%, only 2 studies by Chien et al. (2007) and Nguyen et al. (2019) showed that the rate was below 20% [17,18]. These both studies explain that less support of health staff to provide information about postpartum condition and breastfeeding mechanism since mothers still believe that postpartum mothers should take a lot of rest in bed and there is no breast milk before engorgement [17]. Prelacteal feed also prevent the effort to breastfeed the baby [18].

Fig. 3.

Percentages of exclusive breastfeeding at hospital discharge.

Fig. 4 presented those 2 studies by Chen et al. (2018) and Patel et al. (2003) reported the rate of exclusive breastfeeding one month after birth in most studies were more than 70% in the mothers who had VB [10,19]. Patel et al. (2003) explained that information on benefit of breastfeeding from healthcare providers can increase the rate of exclusive breastfeeding [19].

Fig. 4.

Percentages of exclusive breastfeeding one month after birth.

One study by Leung et al. (2002) showed large differences in the percentages of exclusive breastfeeding one month after birth between CS and VB [20]. They explained that negative experience and feelings on birth affect long-term breast-feeding duration [20].

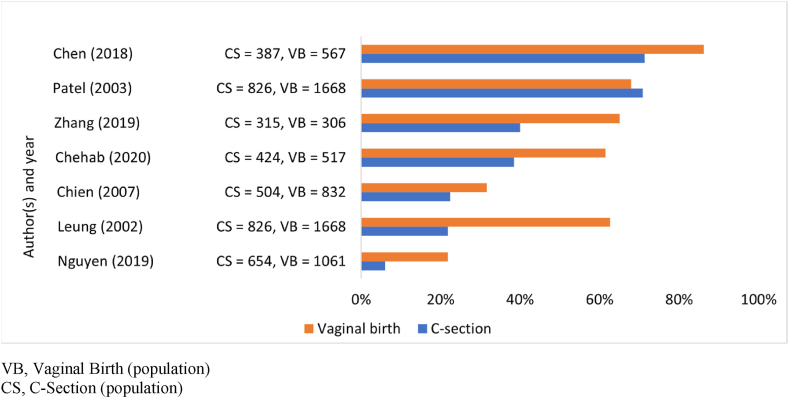

Fig. 5 shows that the different percentage of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers who had CS and VB were narrow. One study by Chalmers et al. (2010) showed that the rate of breastfeeding of mothers who had CS was more than 80% at 3 months after birth [14]. It points out that support from health care practitioners while in hospital stay was important to promote exclusive breastfeeding [14]. However, 1 study by Nguyen et al. (2019) reported the percentages of exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months after birth in Vietnam was less than 5% of mothers who had CS due to introduce of formula feeding [18].

Fig. 5.

Percentages of exclusive breastfeeding three months after birth.

All studies shows that the percentages of exclusive breastfeeding 6 months after birth of mothers who had CS were less than 60% (Fig. 6). Mother's back to work and introduce complementary food are the main reason not to give exclusive breastfeeding [10,[21], [22], [23], [24]]. The differences in the percentages of exclusive breastfeeding 6 months after birth were narrow in both groups. However, one study by Chehab et al. (2020) reported a large difference of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months after birth between CS and VB [25]. They describe that in C-section groups was less of information regarding the benefit of exclusive breastfeeding compared to VB group [25]. In VB group, 24 h rooming-in increase the discussions with health worker regarding the advantages of exclusive breastfeeding.

Fig. 6.

Percentages of exclusive breastfeeding six months after birth.

5. Discussion

5.1. Low percentage of breastfeeding after C-section

This scoping review synthesized data of breastfeeding after C-Section from 1999 to 2022. Surprisingly, the findings revealed that there was no improvement in the rate of breastfeeding after C-section when compared to the results of a previous study by Prior et al. (2012) [3]. Prior et al. performed a systematic review of studies on breastfeeding after C-section published from 1983 to 2011, including data from 33 countries. Their study indicated that C-section was associated with unsuccessful or delayed breastfeeding initiation.

The early initiation of breastfeeding differs significantly between vaginal birth and C-section delivery. Delayed initiation of breastfeeding after a C-section is mainly due to physical discomfort experienced by the mother after birth [26,27], which includes post-operative pain and difficulty in mother-baby attachment. To address this issue, Kintu et al. (2019) recommend the use of pain control measures, such as different kinds of painkillers, and physical support from healthcare providers or families to improve mother-baby attachment for breastfeeding and build the confidence of mothers in breastfeeding their baby [28].

Delayed breast milk onset may also contribute to difficulties with breastfeeding in women who have had a C-section, possibly due to maternal stress or reduced oxytocin secretion, which impairs the hormone pathway to stimulate lactogenesis [5,29,30]. Therefore, early initiation of breastfeeding can encourage the baby to suckle breast milk, increasing the hormones of oxytocin and prolactin, which are important for milk ejection [31].

Socio-cultural beliefs and practices have an impact on breastfeeding [4,17]. Some cultural practices and beliefs may discourage or undermine breastfeeding. For example, some cultures believe that colostrum, the nutrient-rich first milk produced by the breast, is harmful to the infant and should be discarded [17], some cultures believe that formula feeding is superior to breastfeeding [4]. Other cultures discourage breastfeeding in public or consider it indecent [21].

Recently, it is increasingly challenged in a market-driven world where formula milk is heavily marketed and widely available. These challenges are particularly acute in low- and middle-income countries, where access to safe and affordable formula milk is often easier than breastfeeding due to socio-economic and cultural factors. In these contexts, the aggressive marketing and distribution of formula resulting in low breastfeeding rate [32].

To promote breastfeeding, it is important to understand and address the socio-cultural factors that influence breastfeeding practices. This can involve education and awareness campaigns to dispel myths and misconceptions about breastfeeding, raise awareness of the benefits of breastfeeding and the risks associated with the use of breastmilk substitutes, as well as policies and programs that support breastfeeding, such as lactation support in the workplace [32,33].

Furthermore, some women may choose not to breastfeed due to cosmetic reasons, including societal expectations of beauty and the sexualization of breasts [34]. Women's perceptions of their bodies and the societal expectations of beauty can influence their decision to breastfeed. Women may feel uncomfortable or embarrassed about breastfeeding in public due to societal stigma and expectations about modesty and sexualization of breasts. Additionally, some women may be concerned about the potential sexual implications of breastfeeding, which may further influence their decision not to breastfeed.

Although it is important to respect personal choices regarding infant feeding, healthcare providers should provide education and support to women about the benefits of breastfeeding for both the infant and mother. Resources such as breastfeeding-friendly clothing, breast pumps, and nipple care can support women who may have concerns about the cosmetic impact of breastfeeding. Finally, providing a supportive and non-judgmental environment for women to discuss their concerns and ask questions can help them make informed decisions about their infant feeding choices.

5.2. Successful factor of early initiation of breastfeeding after C-section and exclusive breastfeeding

There are several factors that influence the success of breastfeeding in this study. Firstly, hospital policies and healthcare providers play a crucial role in increasing breastfeeding initiation rates among mothers who have had a cesarean section. Counselling, support, and education are vital tasks for healthcare providers to provide accurate information about the breastfeeding process, its benefits, and to dispel myths. Research indicates that breastfeeding education is effective in increasing breastfeeding initiation rates and duration [35]. Antenatal and postnatal care visits that focus on breastfeeding education for mothers, spouses, and families have a significant impact on breastfeeding practices [18,24,36,37,38,39].

Continuing education on lactation and breastfeeding support after C-sections should be provided to healthcare providers. Regular updates on the subject matter can be included in a successful breastfeeding program [40]. Secondly, implemented the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) practice [16], such as skin‐to‐skin contact, rooming in and other practices. The BFHI is a global program to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding. BFHI provides evidence-based guidance to healthcare facilities to implement practices that enable mothers to initiate and sustain breastfeeding, particularly in the crucial first few hours and days after delivery [41]. The initiative has been successful in increasing rates of exclusive breastfeeding and improving infant health outcomes worldwide [42].

In addition to BFHI, some countries have also implemented the Baby-Friendly Primary Care Unit to continue the support for breastfeeding after hospital discharge. Baby-Friendly Primary Care Unit extends the BFHI principles to primary care settings, involves the training of primary care providers, such as midwives and community health workers to support breastfeeding practices, and the provision of ongoing support to mothers and families [43].

Skin-to-skin contact is widely practiced supporting successful breastfeeding after a C-section [44,45], and healthcare providers can facilitate it to increase a mother's confidence and intimacy with her baby. Several studies have shown that skin to skin contact after birth can enhance early initiation of breastfeeding and further exclusive breastfeeding practices [14,16,20,22,44,46]. Additionally, Rooming-in also creates bonding between mother and baby and builds self-efficacy, leading to successful breastfeeding initiation [37,47].

Future interventions in public and private hospitals in many countries should focus on providing comprehensive breastfeeding education and support to mothers, families, and healthcare providers. This could include training healthcare providers in evidence-based breastfeeding practices, providing breastfeeding education to mothers and families, and ensuring that hospital policies and procedures support and promote breastfeeding. Additionally, hospitals could consider implementing breastfeeding-friendly environments, such as providing comfortable and private spaces for mothers to breastfeed or express milk.

5.3. Continue exclusive breastfeeding up to six months

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding for up to 6 months for optimal growth and development, as it provides adequate nutrition and reduces gastrointestinal infections among babies. Although breast milk is low in iron, it is easier for babies to absorb compared to iron in fortified formula [47]. However, the exclusive breastfeeding rate for both CS and VB deliveries is less than 80%, as shown in Fig. 5. This is caused by several factors, including mothers who have returned to work and the introduction of solid food [18,22,23].

To address this problem, providing information about breast milk storage for working mothers and guidelines for introducing complementary foods at around 6 months of age can be helpful. Therefore, the cooperation of various parties, such as health providers, the community, and the mass media, in promoting exclusive breastfeeding can have a significant impact.

The strengths of this study were its rigorous methodological frameworks to conduct and report the scoping review, and a thorough review of studies by three independent reviewers for critical appraisal. The findings of this study can be beneficial in guiding future research, which may help in developing effective interventions for enhancing breastfeeding practices worldwide.

5.3.1. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, it only included peer-reviewed studies published in English and focused specifically on studies reporting on the rates of breastfeeding after C-section and vaginal birth in the same cohort. Secondly, the search was limited by the selection of databases and keywords, which may have caused the exclusion of some relevant articles.

6. Conclusion

This scoping review revealed a low percentage of breastfeeding among mothers who underwent a C-section. A significant disparity in the rate of breastfeeding initiation was observed between the vaginal birth and C-section groups. However, at 3 and 6 months after birth, the gap in exclusive breastfeeding rates between C-section and vaginal birth became narrower. The low rate of breastfeeding initiation and exclusive breastfeeding can be attributed to a lack of breastfeeding knowledge, less optimal mother and baby bonding, and inadequate support from healthcare providers. To address this issue, healthcare providers can provide education and support, and community and mass media can play an essential role in promoting breastfeeding. The implementation of Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiatives, such as the practice of skin-to-skin contact, can also be effective in improving breastfeeding rates after a C-section.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this paper.

Funding or sources of support

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Core-to-Core Program, Asia-Africa Science Platforms (2021–2024, PI: Shigeko Horiuchi).

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Data availability statement

All raw data generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Edward Barroga (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8920-2607), Medical and Nursing Science Editor and Professor of Academic Writing at St. Luke's International University for his editorial review of the manuscript.

Appendix A

Appendix 1.

Summary of results of included studies.

| NO | Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Population | Breastfeeding initiation (%) |

Exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) (%) |

Other factors associated with initiation of breast feeding and exclusive breastfeeding | Notable findings | Summary of Critical Appraisal |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 1 hour | >1 hour-24 hour | At hospital discharge | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | |||||||||

| 1 | Pai et al [48] | 1999 | India | Cross sectional | CS = 95 VB = 115 (Data 1997) | CS = 23.0 VB = 57.0 | CS = 44.0 VB = 51.0 | Prelacteal feed | Moderate quality | |||||

| 2 | Leung et al [20] | 2002 | Hongkong | Cohort | CS = 2,084 VB = 5,593 (Data 1997) | CS = 21.8 VB = 62.6 | Mother age, education, and smoking status, rooming-in, skin to skin | Delayed psychologic reaction of childbirth experience effect the length of breastfeeding period | Moderate quality | |||||

| 3 | Patel et al [19] | 2003 | England | Cohort | CS = 209 VB = 184 (Data 1999-2000) | CS = 70.8 VB = 67.9 | CS = 47.8 VB = 40.6 | Inpatient stay, health providers support | Women after CS who had a longer hospital stay was associated with a higher rate of exclusive breastfeeding | High quality | ||||

| 4 | Butler et al [36] | 2004 | New Zealand | Cohort | CS = 185 VB = 1,062 (Data 2000) | CS = 73.0 VB = 83.1 | Maternal smoking, employment status, twin birth, ANC visit | home visits by a traditional healer have negative associate with exclusive breastfeeding practice. | Moderate quality | |||||

| 5 | Pechlivani et al [37] | 2005 | Greece | Cross sectional | CS = 608 VB = 974 (Data 2001) | CS = 32.7 VB = 67.0 | Mother age, education, and work status, parity, birth of weight, rooming in, knowledgeable | Rooming in have positive effect on exclusive breastfeeding practice. | Moderate quality | |||||

| 6 | Khassawneh et al [21] | 2006 | Jordan | Cross sectional | CS = 46 VB = 296 (Data 2003) | CS = 37.0 VB = 61.5 | Mother employment status | a social culture that restricts breastfeeding in public | Moderate quality | |||||

| 7 | Chien et al [17] | 2007 | Taiwan | Cohort | CS = 699 VB = 1,365 (Data 2002) | CS = 7.6 VB = 19.0 | CS = 14.2 VB = 19.6 | CS = 22.4 VB = 31.6 | CS = 20.7 VB = 28.8 | Mother age, education, partner support, myth | culture believe has a negative impact on exclusive breastfeeding | Moderate quality | ||

| 8 | Liston et al [49] | 2007 | Canada | Cohort | CS = 27,263 VB = 115,666 (Data 1988-2002) | CS = 57.1 VB = 58.9 | Moderate quality | |||||||

| 9 | Chung et al [50] | 2008 | Korea | Cross sectional | CS = 521 VB = 344 (Data 2000-2003) | CS = 39.8 VB = 64.0 a | Mother employment status, birth maturity, parity, ANC visit (breastfeeding counselling), myth, cosmetic. | Some women In Korea refuse to breastfeed because of cosmetic or sexual reasons | Moderate quality | |||||

| 10 | Nakao et al [44] | 2008 | Japan | Cross sectional | CS= 55 VB = 263 (Data 2003) | CS = 9.0 VB = 66.9 | Postpartum hemorrhage, premature birth, skin to skin, prelacteal feed | First breastfeeding timing should be extended to within 120 minutes. |

Moderate quality | |||||

| 11 | Pérez-Ríos et al [51] | 2008 | Puerto Rico | Cross sectional | CS = 598 VB = 1,097 (Data 1990-1996) | CS = 62.0 VB = 66.0 a | Marital status, mother employment status, education, health providers support | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 12 | Al-Sahab et al [22] | 2010 | Canada | Cohort | CS = 1,456 VB = 4,146 (Data 2006) | CS = 11.5 VB = 14.6 | Mother education, BMI, smoking status, mother employment, parity, prelacteal feed | Back to work is the reason for cease breastfeeding | Moderate quality | |||||

| 13 | Chalmers et al [14] | 2010 | Canada | Cross sectional | CS = 2,246 VB = 6,296 (Data 2006) | CS = 89.7 VB = 90.5 | CS = 89.7 VB = 90.5 | CS = 12.5 VB = 15.1 | Skin to skin, health providers support, prelacteal feed | Early contact of maternal infant increases the breastfeeding practice | Moderate quality | |||

| 14 | Zanardo et al [5] | 2010 | Italy | Cohort | CS = 677 VB = 1,496 (Data 2007) | CS = 2.7 VB = 71.5 | CS = 73.9 VB = 87.8 | CS = 55.3 VB = 69.9 | CS = 45.1 VB = 59.0 | Moderate quality | ||||

| 15 | Setegn et al.[38] | 2011 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 18 VB = 557 (Data 2010) | CS = 33.3 VB = 53.5 | PNC visit (breastfeeding counselling) | Traditional practice on baby feeding hinder early initiation of breastfeeding | Moderate quality | |||||

| 16 | Ahluwalia et al [15] | 2012 | United States of America | Cohort | CS = 852 VB = 2,174 (Data 2005-2006) | CS = 82.4 VB = 86.3 | Mothers with planned CS have prepared themselves on postpartum care and breastfeeding which increase breastfeeding practice | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 17 | Liu et al [52] | 2012 | China | Cohort | CS = 22,462 VB = 409,242 (Data 1993-2006) | CS = 89.7 VB = 92.4 | Biological mechanisms after CS associate with low breastfeeding practice | High quality | ||||||

| 18 | Watt et al [53] | 2012 | Canada | Cohort | CS = 826 VB = 1,668 (Data 2006-2008) | CS = 92.7 VB = 92.1 a | Health providers support and community | Community promoting breastfeeding is part of the breastfeeding successful | Moderate quality | |||||

| 19 | Berhe et al [54] | 2013 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 24 VB = 264 (Data 2011) | CS = 33.3 VB = 86.7 | Health workers are more focused on cleaning after childbirth than breastfeeding, causing delayed of initiation of breastfeeding | High quality | ||||||

| 20 | Albokhary et al [55] | 2014 | Saudi Arabia | Cross sectional | CS = 30 VB = 30 (Data 2011) | CS = 0.0 VB = 16.7 | CS = 60.0 VB = 96.7 | Prelacteal feed, skin to skin, rooming in | Mother-baby separated after CS and give formula milk is the common practice in Saudi Arabia | Moderate quality | ||||

| 21 | Seid et al [56] | 2014 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 91 VB = 728 (Data 2012) | CS = 63.3 VB = 89.9 | ANC visit (breastfeeding counselling), knowledgeable | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 22 | Berde et al [57] | 2016 | Nigeria | Cross sectional | CS = 263 VB = 11,508 (Data 2013) | CS = 22.4 VB = 35.1 | Parity, mother employment, baby weight | Previous breastfeeding experience give positive effect on initiation of breastfeeding | High quality | |||||

| 23 | Hobbs et al [58] | 2016 | Canada | Cohort | CS = 739 VB = 2,279 (Data 2008) | CS = 96.8 VB = 98.2 | Health provider support | High quality | ||||||

| 24 | Liben et al [59] | 2016 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 55 VB = 348 (Data 2015) | CS = 22.6 VB = 42.4 | Mother education, parity | Breastfeeding practice in Urban area higher than in rural | Moderate quality | |||||

| 25 | Tewabe et al [39] | 2016 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 38 VB = 367 (Data 2015) | CS = 42.1 VB = 85.3 | ANC visit (breastfeeding counselling), prelacteal feed | Traditional belief on baby feeding hinders the exclusive breastfeeding practice. | Moderate quality | |||||

| 26 | Tilahun et al [60] | 2016 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 29 VB = 380 (Data 2013) | CS = 20.7 VB = 65.8 | Family income, myth | Woman lived with extended family has a lower initiation of breastfeeding | Moderate quality | |||||

| 27 | Woldemichael et al [61] | 2016 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 18 VB = 355 (Data 2014) | CS = 1.6 VB = 65.7 | Mother education | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 28 | Khassawneh et al [23] | 2017 | Jordan | Cross sectional | CS = 191 VB = 309 (Data 2016-2017) | CS = 24.0 VB = 39.0 | Parity, mother employment, knowledgeable | Women belief of inadequate milk supply be a reason not to breastfeed | Moderate quality | |||||

| 29 | Kiani et al [16] | 2017 | Nicaragua | Cross sectional | CS = 100 VB = 147 (Data 2015) | CS = 67.0 VB = 71.4 | CS = 10.7 VB = 14.1 | Prelacteal feed, skin to skin, myth | Early skin to skin contract improves initiation of breastfeeding | High quality | ||||

| 30 | Sharifi et al [62] | 2017 | Iran | Cross sectional | CS = 200 VB = 200 (Data 2014) | CS = 4.2 VB = 3.3 | Moderate quality | |||||||

| 31 | Wallenborn et al [63] | 2017 | United State | Cross sectional | CS = 316,008 VB = 811,530 (Data 2014) | CS = 84.1 VB = 84.9 a | Marital status, partner support | Paternity acknowledgment may associate increasing breastfeeding initiation. | Moderate quality | |||||

| 32 | Chen et al [10] | 2018 | China | Cohort | CS = 387 VB = 567 (Data 2015-2016) | CS = 37.1 VB = 80.0 | CS = 71.3 VB = 86.2 | CS = 60.0 VB = 72.5 | CS = 20.2 VB = 22.4 | Prelacteal feed, mother employment status, complementary food, myth | High quality | |||

| 33 | Belachew et al [64] | 2019 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 185 VB = 287 (Data 2017) | CS = 71.7 VB = 78.4 | ANC visit (breastfeeding counselling) | Health professional focus on lifesaving after CS which ignore initiation of breastfeeding | Moderate quality | |||||

| 34 | Ezeh et al [65] | 2019 | ECOWAS country | Cross sectional | CS = 2,966 VB = 73,763 (Data 2010-2018) | CS = 3.5 VB = 96.3 | Parity, knowledgeable | Socio-cultural beliefs regarding gender different, which female baby are more likely to have early initiation of breastfeeding than male baby | High quality | |||||

| 35 | Gebremeskel et al [66] | 2019 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 28 VB = 775 (Data 2018) | CS = 35.7 VB = 61.5 | Mother education | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 36 | John et al [4] | 2019 | Ethiopia | Cohort | CS = 109 VB = 4,012 (Data 2016) | CS = 1.4 VB = 98.6 | Parity | Cultural beliefs in Africa that male baby privileged to receive prelacteal which make them strong and healthy | Moderate quality | |||||

| 37 | Karim et al [24] | 2019 | Bangladesh | Cohort | CS = 778 VB = 2,384 (Data 2014) | CS = 29.1 VB = 98.6 | PNC visit (breastfeeding counselling) | High quality | ||||||

| 38 | Nguyen et al. [18] | 2019 | Vietnam | Cohort | CS = 654 VB = 1,061 (Data 2015) | CS = 4.4 VB = 54.5 | CS = 6.7 VB = 26.4 | CS = 6.0 VB = 21.8 | CS = 4.9 VB = 18.2 | CS = 0.5 VB = 2.9 | Mother employment status, mother smoking and alcohol consumed, PNC visit, health providers support, prelacteal feed, rooming in | Moderate quality | ||

| 39 | Taha et al [67] | 2019 | Abu Dhabi | Cross sectional | CS = 491 VB = 1133 (Data 2017) | CS = 43.0 VB = 71.0 | CS = 29.0 VB = 57.0 | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 40 | Hernández-Vásquez [45] | 2019 | Peru | Cross sectional | CS = 6,324 VB = 13,271 (Data 2013-2018) | CS = 11.0 VB = 71.1 | Skin to skin, mother education | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 42 | Zhang et al [11] | 2019 | China | Cohort | CS = 333 VB = 315 (Data 2011-2013) | CS = 35.7 VB = 54.9 | CS = 40.0 VB = 65.0 | CS = 20.7 VB = 29.8 | CS = 17.8 VB = 25.4 | Prelacteal feed | High quality | |||

| 42 | Ali et al [46] | 2020 | Bangladesh | Cross sectional | CS = 359 VB = 2,362 (Data 2017) | CS = 51.2 VB = 72.4 | Rooming in, skin to skin | High quality | ||||||

| 43 | Apanga et al [68] | 2020 | Ghana | Cross sectional | CS = 1,663 VB = 13,642 (Data 2017-2018) | CS = 26.6 VB = 54.6 | Baby weight | High quality | ||||||

| 44 | Chehab et al [25] | 2020 | Lebanon | Cross sectional | CS = 424 VB = 517 (Data 2011-2012) | CS = 38.5 VB = 61.5 | CS = 32.7 VB = 67.3 | Rooming in, skin to skin, obese mother | Obese mothers was shorter the duration of breastfeeding than normal weight mothers due to insufficient milk | High quality | ||||

| 45 | Gargamo et al [69] | 2020 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 50 VB = 333 (Data 2019) | CS = 9.7 VB = 90.3 | Mother illness, ANC (breastfeeding counselling) | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 46 | Gayatri et al [40] | 2020 | Indonesia | Cross sectional | CS = 1,268 VB = 5,348 (Data 2017) | CS = 36.8 VB = 61.2 | skin to skin, birth attendance | Update the health providers’ knowledge on breastfeeding is key factor of successful breastfeeding | High quality | |||||

| 47 | Paksoy et al [70] | 2020 | Turkey | Cohort | CS = 417 VB = 360 (Data 2013) | CS = 51.6 VB = 63.9 | Mother education | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 48 | Ragusa et al [71] | 2020 | Italy | Cross sectional | CS = 1,488 VB = 2,325 (Data 2016-2018) | CS = 35.0 VB = 51.0 | Mother education, health provider support, partner support | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 49 | Seidu et al [72] | 2020 | Papua New Guinea | Cross sectional | CS = 102 VB = 3,096 (Data 2016-2018) | CS = 26.5 VB = 61.0 | Skin to skin | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 50 | Yanadar et al [73] | 2020 | Myanmar | Cross sectional | CS = 332 VB = 1174 (Data 2015-2016) | CS = 56.6 VB = 71.1 | CS = 55.9 VB = 50.9 | Birth order, ANC visit, | High quality | |||||

| 51 | Yohannes et al [74] | 2020 | Ethiopia | Cross sectional | CS = 29 VB = 304 (Data 2019) | CS = 44.8 VB = 83.8 | ANC visit, knowledgeable, mother employment status, breast condition (Normal/abnormal) | High quality | ||||||

| 52 | Appiah et al [75] | 2021 | Sub-Saharan | Cross sectional | CS = 3,051 VB = 56,987 (Data 2010-2018) | CS = 34.6 VB = 57.0 | Parity, knowledgeable, ANC visit | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 53 | Duong et al [76] | 2022 | Vietnam | Cohort | CS = 274 VB = 280 (Data 2019-2021) | CS = 24.5 VB = 57.1 | Moderate quality | |||||||

| 54 | Mary et al [77] | 2022 | India | Cross sectional | CS = 77 VB = 31 (Data 2019) | CS = 35.1 VB = 64.5 | Birth weight, knowledgeable | Moderate quality | ||||||

| 55 | Stipelman et al [78] | 2022 | United State | Cohort | CS = 727 VB = 2588 (Data 2017) | CS = 8.9 VB = 35.8 | CS = 40.1 VB = 69.3 | Breastfeeding initiation in the first 24 hours was associated with successful breastfeeding duration for all infants. | High quality | |||||

indicate no clear statement whether this rate of initiation of breastfeeding was within one hour after birth

Appendix 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

| Section | ITEM | Prisma-ScR checklist item | Reported on page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | Title |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Abstract |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | p. 2-3 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | p. 4 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | NA |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | p. 4-5 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | p. 5 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | p. 5 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | p. 5-6 |

| Data charting process | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | p. 6 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | Operational definition p. 6-7 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | p. 6 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | p. 9 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | p. 8 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | p. 8-9 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | Table 1 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | Table 1 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | Table 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | p. 25-28 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | p. 28 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | p. 28-29 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | p.30 |

From: Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-

ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. ;169:467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2014. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Policy Brief Series.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NHD-14.2 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K., Ganchimeg T., Ota E., Vogel J.P., Souza J.P., Laopaiboon M., Castro C.P., Jayaratne K., Ortiz-Panozo E., Lumbiganon P., Mori R. Prevalence of early initiation of breastfeeding and determinants of delayed initiation of breastfeeding: secondary analysis of the WHO Global Survey. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/srep44868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prior E., Santhakumaran S., Gale C., Philipps L.H., Modi N., Hyde M.J. Breastfeeding after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of world literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012;95(5):1113–1135. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.030254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.John J.R., Mistry S.K., Kebede G., Manohar N., Arora A. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Ethiopia: a population-based study using the 2016 demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanardo V., Svegliado G., Cavallin F., Giustardi A., Cosmi E., Litta P., Trevisanuto D. Elective cesarean delivery: does it have a negative effect on breastfeeding? Birth. 2010;37(4):275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.2010.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althabe F., Belizán J.M. Caesarean section: the paradox. Lancet. 2006;368(9546):1472–1473. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien P. Global rising rates of caesarean sections. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021;128(5):781–782. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenabi E., Khazaei S., Bashirian S., Aghababaei S., Matinnia N. Reasons for elective cesarean section on maternal request: a systematic review. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1587407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoine C., Young B.K. Cesarean section one hundred years 1920–2020: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. J. Perinat. Med. 2020;49(1):5–16. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2020-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C., Yan Y., Gao X., Xiang S., He Q., Zeng G., Liu S., Sha T., Li L. Influences of cesarean delivery on breastfeeding practices and duration: a prospective cohort study. J. Hum. Lactation. 2018;34(3):526–534. doi: 10.1177/0890334417741434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F., Cheng J., Yan S., Wu H., Bai T. Early feeding behaviors and breastfeeding outcomes after cesarean section. Breastfeed. Med. 2019;14(5) doi: 10.1089/bfm.2018.0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joanna Briggs Institutes . 2017. Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses. From. https://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical|_appraisal_tools. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. BMC Syst. Rev. 2016;5(1) doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chalmers B., Kaczorowski J., Darling E., Heaman M., Fell D.B., O'Brien B., Lee L. Cesarean and vaginal birth in Canadian women: a comparison of experiences. Birth. 2010;37(1):44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.2009.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahluwalia I.B., Li R., Morrow B. Breastfeeding practices: does method of delivery matter? Matern. Child Health J. 2012;16(S2):231–237. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiani S.N., Rich K.M., Herkert D., Safon C., Pérez-Escamilla R. Delivery mode and breastfeeding outcomes among new mothers in Nicaragua. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017;14(1) doi: 10.1111/mcn.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chien L.-Y., Tai C.-J. Effect of delivery method and timing of breastfeeding initiation on breastfeeding outcomes in Taiwan. Birth. 2007;34(2):123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536x.2007.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen P.T., Binns C.W., Vo Van Ha A., Nguyen C.L., Khac Chu T., Duong D.V., Do D.V., Lee A.H. Caesarean delivery associated with adverse breastfeeding practices: a prospective cohort study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019;40(5):644–648. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2019.1647519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel R.R., Liebling R.E., Murphy D.J. Effect of operative delivery in the second stage of labor on breastfeeding success. Birth. 2003;30(4):255–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung G. Breast-feeding and its relation to smoking and mode of delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;99(5):785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)01940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khassawneh M., Khader Y., Amarin Z., Alkafajei A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of breastfeeding in the north of Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2006;1(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Sahab B., Lanes A., Feldman M., Tamim H. Prevalence and predictors of 6-month exclusive breastfeeding among Canadian women: a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khasawneh W., Khasawneh A.A. Predictors and barriers to breastfeeding in north of Jordan: could we do better? Int. Breastfeed. J. 2017;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-017-0140-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karim F., Khan A.N.S., Tasnim F., Chowdhury M.A.K., Billah S.M., Karim T., Arifeen S.E., Garnett S.P. Prevalence and determinants of initiation of breastfeeding within one hour of birth: an analysis of the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 2014. PLoS One. 2019;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chehab R.F., Nasreddine L., Zgheib R., Forman M.R. Exclusive breastfeeding during the 40-day rest period and at six months in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2020;15(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-020-00289-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baxter J. Women's experience of infant feeding following birth by caesarean section. Br. J. Midwifery. 2006;14(5):290–295. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2006.14.5.21054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tully K.P., Ball H.L. Maternal accounts of their breast-feeding intent and early challenges after caesarean childbirth. Midwifery. 2014;30(6):712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kintu A., Abdulla S., Lubikire A., Nabukenya M.T., Igaga E., Bulamba F., Semakula D., Olufolabi A.J. Postoperative pain after cesarean section: assessment and management in a tertiary hospital in a low-income country. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3911-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans K.C. Effect of caesarean section on breast milk transfer to the normal term newborn over the first week of life. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(5):380F382. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.5.f380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott J.A., Binns C.W., Oddy W.H. Predictors of delayed onset of lactation. Matern. Child Nutr. 2007;3(3):186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uvnäs-Moberg K., Ekström-Bergström A., Berg M., Buckley S., Pajalic Z., Hadjigeorgiou E., et al. Maternal plasma levels of oxytocin during physiological childbirth – a systematic review with implications for uterine contractions and central actions of oxytocin. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2365-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pérez-Escamilla R., Tomori C., Hernández-Cordero S., Baker P., Barros A.J., Bégin F., Chapman D.J., Grummer-Strawn L.M., McCoy D., Menon P., Ribeiro Neves P.A., Piwoz E., Rollins N., Victora C.G., Richter L. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet. 2023;401(10375):472–485. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01932-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rollins N.C., Bhandari N., Hajeebhoy N., Horton S., Lutter C.K., Martines J.C., Piwoz E.G., Richter L.M., Victora C.G. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387(10017):491–504. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bucher M.K., Spatz D.L. Ten-year systematic review of sexuality and breastfeeding in medicine, psychology, and gender studies. Nurs. Women's Health. 2019;23(6):494–507. doi: 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Willumsen J. World Health Organization; 2014. WHO | Breastfeeding Education for Increased Breastfeeding Duration.entity/elena/bbc/breastfeeding_education/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler S., Williams M., Tukuitonga C., Paterson J. Factors associated with not breastfeeding exclusively among mothers of a cohort of Pacific infants in New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 2004;117(1195):U908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pechlivani F., Vassilakou T., Sarafidou J., Zachou T., Anastasiou C.A., Sidossis L.S. Prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding during hospital stay in the area of Athens, Greece. Acta Paediatr. 2007;94(7):928–934. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Setegn T., Gerbaba M., Belachew T. Determinants of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers in Goba Woreda, South East Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Publ. Health. 2011;11(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tewabe T. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers in Motta town, East Gojjam zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia, 2015: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gayatri M., Dasvarma G.L. Predictors of early initiation of breastfeeding in Indonesia: a population-based cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.UNICEF . 2018. Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative.https://www.unicef.org/documents/baby-friendly-hospital-initiative Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Escamilla R., Martinez J.L., Segura-Pérez S. Impact of the Baby-friendly Hospital Initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016;12(3):402–417. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alves A.L., Oliveira M.I., Moraes J.R. Breastfeeding-friendly primary care unit initiative and the relationship with exclusive breastfeeding. Rev. Saude Publica. 2013;47(6):1130–1140. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2013047004841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakao Y., Moji K., Honda S., Oishi K. Initiation of breastfeeding within 120 minutes after birth is associated with breastfeeding at four months among Japanese women: a self-administered questionnaire survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2008;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vásquez A.H., Chacón-Torrico H. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Peru: analysis of the 2018 demographic and family health survey. Epidemiol. Health. 2019;41 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2019051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali N.B., Karim F., Billah S.K.M., Hoque D.M.D.E., Khan A.N.S., Hasan M.M., Simi S.M., Arifeen S.E.L., Chowdhury M.A.K. Are childbirth location and mode of delivery associated with favorable early breastfeeding practices in hard to reach areas of Bangladesh? PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaafar S.H., Ho J.J., Lee K.S. Rooming-in for new mother and infant versus separate care for increasing the duration of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016;2016(8):CD006641. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006641.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pai M., Sundaram P., Radhakrishnan K.K., Thomas K., Muliyil J.P. A high rate of caesarean sections in an affluent section of Chennai: is it cause for concern? Natl. Med. J. India. 1999;12(4):156–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liston F.A., Allen V.M., O'Connell C.M., Jangaard K.A. Neonatal outcomes with caesarean delivery at term. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008;93(3):F176–F182. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.112565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chung W., Kim H., Nam C.-M. Breast-feeding in South Korea: factors influencing its initiation and duration. Publ. Health Nutr. 2008;11(3):225–229. doi: 10.1017/s136898000700047x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pérez-Ríos N., Ramos-Valencia G., Ortiz A.P. Cesarean delivery as a barrier for breastfeeding initiation: the Puerto Rican experience. J. Hum. Lactation. 2008;24(3):293–302. doi: 10.1177/0890334408316078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu X., Zhang J., Liu Y., Li Y., Li Z. The association between cesarean delivery on maternal request and method of newborn feeding in China. PLoS One. 2012;7(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watt S., Sword W., Sheehan D., Foster G., Thabane L., Krueger P., Landy C.K. The effect of delivery method on breastfeeding initiation from the the ontario mother and infant study (TOMIS) III. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(6):728–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berhe H., Mekonnen B., Bayray A., Berhe H. Determinants of breast feeding practices among mothers attending public health facilities, Mekelle, northern Ethiopia; a cross sectional study. Int. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. Res. 2013;4(2):650. doi: 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.4(2).650-60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albokhary A.A., James J.P. Does cesarean section have an impact on the successful initiation of breastfeeding in Saudi Arabia? Saudi Med. J. 2014;35(11):1400–1403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seid A. Vaginal birth and maternal knowledge on correct breastfeeding initiation time as predictors of early breastfeeding initiation: lesson from a community-based cross-sectional study. Int. Sch. Res. Notices. 2014;4:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/904609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berde A.S., Yalcin S.S. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria: a population-based study using the 2013 demograhic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hobbs A.J., Mannion C.A., McDonald S.W., Brockway M., Tough S.C. The impact of caesarean section on breastfeeding initiation, duration and difficulties in the first four months postpartum. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0876-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liben M.L., Yesuf E.M. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Amibara district, Northeastern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tilahun G., Degu G., Azale T., Tigabu A. Prevalence and associated factors of timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers at Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2016;11(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-016-0086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Woldemichael B., Kibie Y. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and its associated factors among mothers in Tiyo Woreda, Arsi zone, Ethiopia: a community-based cross sectional study. Clin. Mother Child Health. 2016;13(221):2. doi: 10.4172/2090-7214.1000221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharifi F., Nouraei S., Sharifi N. Factors affecting the choice of type of delivery with breast feeding in Iranian mothers. Electron. Phys. 2017;9(9):5265–5269. doi: 10.19082/5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wallenborn J.T., Chambers G.J., Masho S.W. The role of paternity acknowledgment in breastfeeding noninitiation. J. Hum. Lactation. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0890334417743209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belachew A. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers of infants age 0–6 months old in Bahir Dar City, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2017: a community based cross-sectional study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ezeh O., Ogbo F., Stevens G., Tannous W., Uchechukwu O., Ghimire P., Agho K. Factors associated with the early initiation of breastfeeding in economic community of west african states (ECOWAS) Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2765. doi: 10.3390/nu11112765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gebremeskel S.G., Gebru T.T., Gebrehiwot B.G., Meles H.N., Tafere B.B., Gebreslassie G.W., Welay F.T., Mengesha M.B., Weldegeorges D.A. Early initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers of aged less than 12 months children in rural eastern zone, Tigray, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes. 2019;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taha Z., Ali Hassan A., Wikkeling-Scott L., Papandreou D. Prevalence and associated factors of caesarean section and its impact on early initiation of breastfeeding in abu dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Nutrients. 2019;11(11):2723. doi: 10.3390/nu11112723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Apanga P.A., Kumbeni M.T. Prevalence and predictors of timely initiation of breastfeeding in Ghana: an analysis of 2017–2018 multiple indicator cluster survey. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-021-00383-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gargamo D., Hidoto K., Abiso T. Prevalence and associated factors on timely initiation of breastfeeding among mothers of children age less than 12 Months in Wolaita Sodo City, Wolaita, Ethiopia. Int. J. Pediatr. 2020;8(12):12565–12574. doi: 10.22038/ijp.2020.46817.3802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paksoy Erbaydar N., Erbaydar T. Relationship between caesarean section and breastfeeding: evidence from the 2013 Turkey demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1) doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2732-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ragusa R., Giorgianni G., Marranzano M., Cacciola S., La Rosa V.L., Giarratana A., Altadonna V., Guardabasso V. Breastfeeding in hospitals: factors influencing maternal choice in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17(10):3575. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seidu A.-A., Ahinkorah B.O., Agbaglo E., Dadzie L.K., Tetteh J.K., Ameyaw E.K., Salihu T., Yaya S. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Papua New Guinea: a population-based study using the 2016-2018 demographic and health survey data. Arch. Publ. Health. 2020;78(1) doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yadanar, Mya K.S., Witvorapong N. Determinants of breastfeeding practices in Myanmar: results from the latest nationally representative survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0239515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yohannes E., Tesfaye T. Timely initiation of breastfeeding and associated factors among mothers who have infants less than six months of age in Gunchire town, southern Ethiopia 2019. Clin. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. 2020;3:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Appiah F., Ahinkorah B.O., Budu E., Oduro J.K., Sambah F., Baatiema L., Ameyaw E.K., Seidu A.-A. Maternal and child factors associated with timely initiation of breastfeeding in sub-Saharan Africa. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2021;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s13006-021-00402-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duong D.T.T., Binns C., Lee A., Zhao Y., Pham N.M., Hoa D.T.P., Ha B.T.T. Intention to exclusively breastfeed is associated with lower rates of cesarean section for nonmedical reasons in a cohort of mothers in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2022;19(2):884. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mary J., Sindhuri R., Kumaran A.A., Dongre A.R. Early initiation of breastfeeding and factors associated with its delay among mothers at discharge from a single hospital. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2022;65(4):201–208. doi: 10.3345/cep.2021.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stipelman C.H., Stoddard G.J., Bennion J., Young P.C., Brown L.L. Real-time breastfeeding documentation: timing of breastfeeding initiation and outpatient duration. Acad. Pediatr. 2022;(22):S1876–S2859. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.07.010. 00355-2. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All raw data generated during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.