Introduction

The rapid increase in publications related to artificial intelligence (AI) in medical imaging has pinpointed the need for transparent and organized research reporting. Publications on AI research should provide the necessary information to ensure adherence to high scientific standards while allowing the independent reproduction of the research. Reproducibility is necessary to enable clinical translation and adoption of AI algorithms that may otherwise remain on paper. For this purpose, a series of tools have been developed to guide the comprehensive reporting of AI research to promote research reproducibility, adherence to ethical standards, comprehensibility of research manuscripts, and publication of scientifically valid results. The use of such guidelines has been encouraged or mandated by scientific journals to allow appropriate evaluation of research output during the review process.

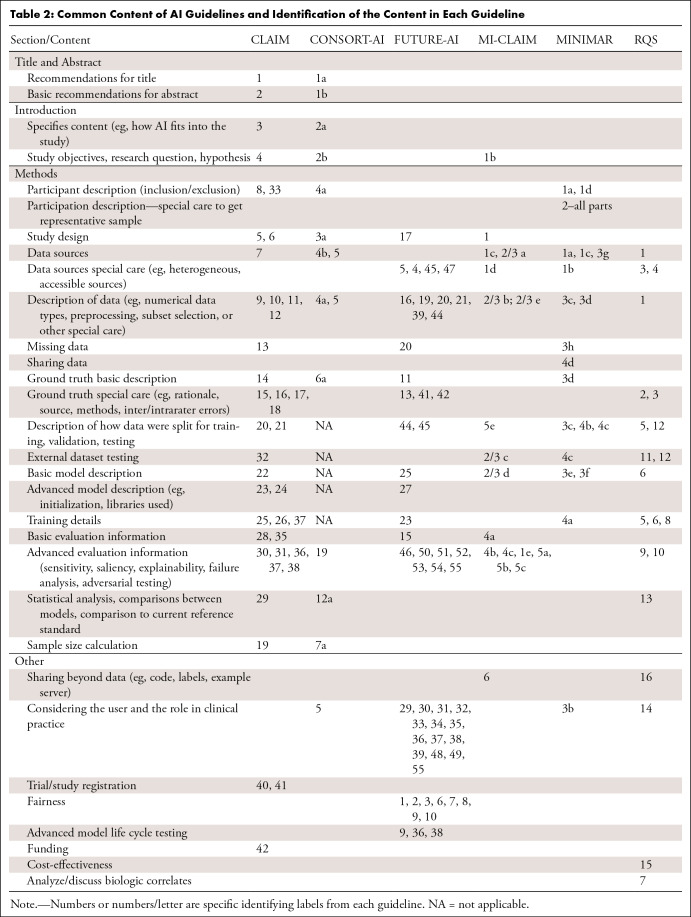

The majority of existing guidelines and checklists allow authors to confirm the inclusion of specific information in each manuscript section: Title, Abstract, Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. The content of these checklists highlights the minimum information a journal requires for the publication of an AI study, providing researchers with guidelines to conduct their research while also easing and standardizing the review process. Existing guidelines or guidelines under development specific to AI include CLAIM (Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging), STARD-AI (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Study-AI), CONSORT-AI (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials–AI), SPIRIT-AI (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials-AI), FUTURE-AI (Fairness Universality Traceability Usability Robustness Explainability-AI), MI-CLAIM (Minimum Information about Clinical Artificial Intelligence Modeling), MINIMAR (Minimum Information for Medical AI Reporting), and RQS (Radiomics Quality Score). In this editorial, we compare these guidelines and their content to help readers find the best guideline for their research. Table 1 provides a high-level overview including a summary of guidelines’ availability, purpose, and format and brief information about which manuscript sections they address. Table 2 details specific content for each manuscript section and indicates which checklists include this information.

Table 1:

Comparison of Guideline Structure and Components

Table 2:

Common Content of AI Guidelines and Identification of the Content in Each Guideline

CLAIM

CLAIM is an AI-specific guideline that defines a baseline of information that should be included in manuscripts presenting AI applications in medical imaging (1). CLAIM provides a checklist to ensure researchers report key study parameters that will allow appropriate and accurate interpretation of the study, its results, and the generalizability of the findings. CLAIM focuses on AI model development studies and ensures that the study is registered and encourages data and code availability and reporting of potential sources of bias. STARD-AI, currently under development, is the AI-specific version of STARD (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) and is expected to cover similar concerns as CLAIM (2). Although published in a radiology-related journal, CLAIM is not limited to radiology and focuses on medical imaging more broadly.

CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI

For studies dealing with clinical trials, CONSORT-AI (3) and its accompanying guideline SPIRIT-AI represent the extension of the CONSORT statement about clinical trials that includes additional or extension items that are important for randomized controlled trials dealing with AI applications. SPIRIT-AI is specific to publication of clinical trial protocols. Both are mostly concerned with randomized controlled trials of AI tools that have previously been developed. In contrast to other guidelines, CONSORT-AI and SPIRIT-AI require information relevant to trial design such as patient randomization, details on patient recruitment strategies, and harm analysis.

FUTURE-AI

FUTURE-AI (4) is a set of principles to guide AI developments in medical imaging to increase safety, trust, and clinical adoption. It emphasizes fairness, usability, robustness, and explainability. Robustness entails the use of phantoms and heterogeneous training data to assure that AI models achieve equity. The FUTURE-AI checklist does not deal with manuscript structure but aims to guide all steps of AI development including concepts that are not found in other guidelines such as “clinical conception,” “end-user requirement gathering,” and “AI deployment and monitoring.” This guideline includes a separate section on fairness where it attempts to extensively assess all potential sources of bias in AI systems.

MI-CLAIM and MINIMAR

Bias is also extensively discussed in MI-CLAIM (5), which allows direct assessment of clinical impact (fairness/bias), to allow replication of technical design of clinical AI studies. The MI-CLAIM is similar to CLAIM but less extensive on what should be included in study reporting. MI-CLAIM promotes the appropriate assessment of model performance from multiple perspectives—model performance, clinical performance, explainability/"examination."

A similar style to MI-CLAIM has been adopted by MINIMAR (6), which requests general model information, with more emphasis on real-world use (data source and validation from another setting). Like MI-CLAIM, it is less extensive compared with CLAIM.

Topic-specific Guidelines

Some of the existing guidelines are topic specific (eg, for randomized trials or radiomics) and should be preferred when presenting research on the respective topic. For research reporting on AI trials, CONSORT-AI (3) and SPIRIT-AI represent the AI versions of the CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) (7) and SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) (8) guidelines. These facilitate reporting of clinical trials related to AI models that have been previously developed. CONSORT-AI includes points on participant recruitment, treatment group construction, patient randomization, and analysis of harm that cannot be found in other guidelines. In the case of clinical trial protocols, SPIRIT-AI should be selected.

Another topic-specific guideline is the Radiomics Quality Score (RQS) proposed by Lambin et al (9). The majority of publications on radiomics include AI models to extract radiomics features, to automatically segment regions of interest for feature extraction, or most commonly for classification purposes using radiomics data. Therefore, RQS is a checklist that scores the quality of radiomics manuscripts based on criteria related to radiomics analysis, including segmentation parameters, feature selection, and feature reproducibility. RQS also deals with the AI aspect of radiomics including the evaluation metrics for AI algorithms, model calibration, decision curve analysis, and error estimation. However, in contrast to other checklists, it does not deal with manuscript structure, and the AI section of the score is significantly limited. In addition, it needs to be stressed that caution should be exercised when using the score because no inter- or intrarater reproducibility analysis was published in the original RQS publication. For this reason, in studies reporting machine learning models based on radiomics data, the use of an additional AI-specific checklist is recommended.

Following a combination of guidelines may be appropriate to cover different aspects of research work. Such a combination could be made between guidelines that deal with the process of AI development such as FUTURE-AI and guidelines that ensure transparent manuscript preparation and enable seamless reviewing and reproduction of the work such as CLAIM. However, one should consult the editorial policy of the target journal to make sure that the guideline used fulfills the requirement of the publisher. Nonetheless, it should be stressed that guidelines are not publication passes but rather guarantors of publication completeness.

Future Guidelines

At this time, additional guidelines have been announced but are not yet published. These include the AI versions of the well-known TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model of Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) and PROBAST (Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool) guidelines (10,11). TRIPOD-AI and PROBAST-AI represent work in progress and their additions to existing guidelines remain to be seen.

Conclusion

The guidelines presented here encourage authors to comprehensively present information related to AI work and allow appropriate evaluation of manuscripts during the review process. Selection of the appropriate guideline should be based on the topic, the requirements of the target journal, and the content of each guideline; one may wish to consider applying a combination of guidelines when appropriate for overlapping indications. As the field of AI evolves and new algorithms arise, we expect to see new and updated reporting standards to assure the high quality of the science and application of AI in medicine.

Footnotes

Authors declared no funding for this work.

Disclosures of conflicts of interest: M.E.K. Board member of the European Society of Medical Imaging Informatics; member of the trainee editorial board of Radiology: Artificial Intelligence. A.A.G. CIHR Postdoctoral Fellowship; Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance at Stanford; patent planned, issued, or pending for US11080857B2 - Systems and methods for segmenting an image; founder and shareholder in NeuralSeg, Ltd; trainee editorial board of Radiology: Artificial Intelligence. A.S.T. Trainee editorial board of Radiology: Artificial Intelligence. C.E.K. Editor of Radiology: Artificial Intelligence (salary support paid to institution).

References

- 1. Mongan J , Moy L , Kahn CE Jr . Checklist for Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging (CLAIM): A guide for authors and reviewers . Radiol Artif Intell 2020. ; 2 ( 2 ): e200029 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bossuyt PM , Reitsma JB , Bruns DE , et al. ; STARD Group . STARD 2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies . Radiology 2015. ; 277 ( 3 ): 826 – 832 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu X , Cruz Rivera S , Moher D , Calvert MJ , Denniston AK ; SPIRIT-AI and CONSORT-AI Working Group . Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension . Nat Med 2020. ; 26 ( 9 ): 1364 – 1374 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lekadir K , Osuala R , Gallin C , et al . FUTURE-AI : Guiding principles and consensus recommendations for trustworthy artificial intelligence in medical imaging . arXiv 2109.09658v3 [preprint]https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.09658. Posted September 29, 2021. Accessed February 2023 . [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norgeot B , Quer G , Beaulieu-Jones BK , et al . Minimum information about clinical artificial intelligence modeling: the MI-CLAIM checklist . Nat Med 2020. ; 26 ( 9 ): 1320 – 1324 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hernandez-Boussard T , Bozkurt S , Ioannidis JPA , Shah NH . MINIMAR (MINimum Information for Medical AI Reporting): Developing reporting standards for artificial intelligence in health care . J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020. ; 27 ( 12 ): 2011 – 2015 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piaggio G , Elbourne DR , Pocock SJ , Evans SJW , Altman DG ; CONSORT Group . Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement . JAMA 2012. ; 308 ( 24 ): 2594 – 2604 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan A-W , Tetzlaff JM , Gøtzsche PC , et al . SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials . BMJ 2013. ; 346 ( jan08 15 ): e7586 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lambin P , Leijenaar RTH , Deist TM , et al . Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine . Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017. ; 14 ( 12 ): 749 – 762 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Collins GS , Reitsma JB , Altman DG , Moons KG . Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement . Ann Intern Med 2015. ; 162 ( 1 ): 55 – 63 . Erratum in: Ann Intern Med 2015;162(8):600 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolff RF , Moons KGM , Riley RD , et al . PROBAST: A tool to assess the risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies . Ann Intern Med 2019. ; 170 : 51 – 58 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]