Abstract

Bis-amidate derivatives have been viewed as attractive phosphonate prodrug forms because of their straightforward synthesis, lack of phosphorus stereochemistry, plasma stability and nontoxic amino acid metabolites. However, the efficiency of bis-amidate prodrug forms is unclear, as prior studies on this class of prodrugs have not evaluated their activation kinetics. Here, we synthetized a small panel of bis-amidate prodrugs of butyrophilin ligands as potential immunotherapy agents. These compounds were examined relative to other prodrug forms delivering the same payload for their stability in plasma and cell lysate, their ability to stimulate T cell proliferation in human PBMCs, and their activation kinetics in a leukemia co-culture model of T cell cytokine production. The bis-amidate prodrugs demonstrate high plasma stability and improved cellular phosphoantigen activity relative to the free phosphonic acid. However, the efficiency of bis-amidate activation is low relative to other prodrugs that contain at least one ester such as aryl-amidate, aryl-acyloxyalkyl ester, and bis-acyloxyalkyl ester forms. Therefore, bis-amidate prodrugs do not drive rapid cellular payload accumulation and they would be more useful for payloads in which slower, sustained-release kinetics are preferred.

Keywords: phosphoantigen, phosphonamidate prodrug, butyrophilin, ligand, isoprenoid

TOC Graphic

Phosphates and their more metabolically stable phosphonate analogs are often desirable in drug candidates,1 yet these functional groups have poor membrane permeability because they are highly charged at physiological pH.2 As there are few bio-isosteres available, it has become the norm to develop phosphonate-containing drugs with intracellular targets in prodrug forms that mask their negative charge and boost cellular uptake. Various prodrug designs have been applied, including bis-amidate forms,3–4 yet surprisingly few studies actually compare the efficiency of the different configurations. Most commonly, a report will describe a single prodrug form at a single end point, making it difficult to extract efficiency data from the literature.

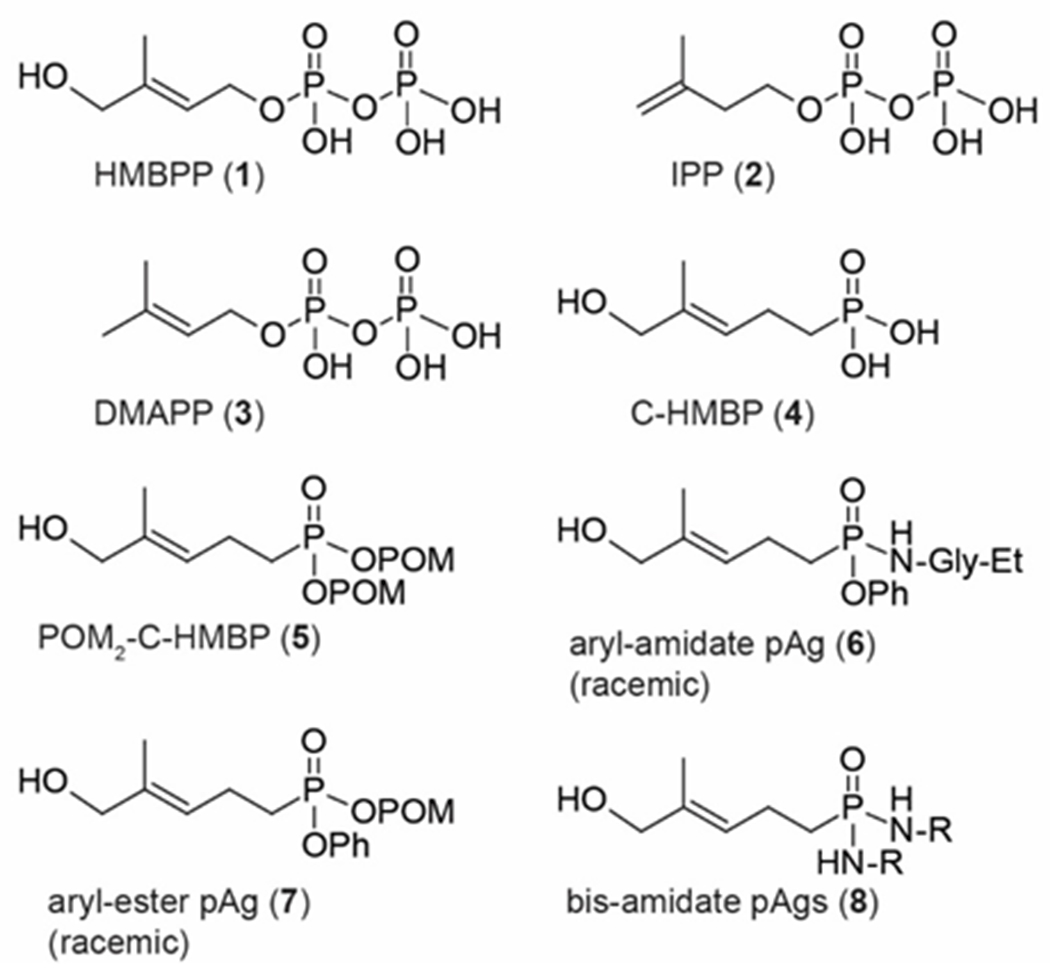

Immunotherapy of cancers that utilizes T cells has great clinical potential.5 T cells that express a γδ T cell receptor (TCR) are of interest because they may provide therapeutic advantages relative to canonical αβ T cells.6–10 The primary γδ T cell population found in peripheral blood, the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, are activated by small organophosphorus compounds known as phosphoantigens,11 which are highly-charged ligands of the intracellular B30.2 domain of BTN3A1.12–13 The most potent phosphoantigen, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl diphosphate (HMBPP, 1), is the bacterial precursor to both isopentenyl diphosphate (2, IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (3, DMAPP) which are the bedrocks of the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways in all organisms and weak phosphoantigens themselves (Figure 1).14 While the mechanism(s) of phosphoantigen function would benefit from further clarification,15 both HMBPP and its monophosphonate analog C-HMBP (4)16 activate the HBMPP receptor complex resulting in detection by the Vγ9Vδ2 TCR.17–18

Figure 1. Natural phosphoantigens, a synthetic analog, and various prodrug forms.

HMBPP (1) is the prototypical natural phosphoantigen (pAg). IPP (2) and DMAPP (3) are ubiquitous but weaker natural phosphoantigens. C-HMBP (4) is a synthetic analog of HMBPP (1). Various prodrug forms of C-HMBP (5-8) designed to improve its potency, including bis-amidates (8, this work).

Like all phosphates and phosphonates, the phosphoantigens have a high degree of negative charge at physiological pH and low membrane permeability. When produced naturally by intracellular microbes, they can access the intracellular binding site on BTN3A1.19–21 However, when exogenous phosphoantigens are administered in a prophylactic or therapeutic context, low membrane permeability limits access to the binding site. To overcome this cellular penetration issue, we have turned to prodrug strategies that temporarily mask the acidic phosphonate of C-HMBP.22 Bis-acyloxyalkyl prodrugs such as POM2-C-HMBP (5) improved cellular potency relative to the free phosphonate, which serves as an important proof-of-principle supporting the prodrug strategy for more efficient delivery of these molecules.23 However, some of these prodrug forms exhibit their own drawbacks, including lower plasma stability than would be required for distribution to blood cells or peripheral tissues.

Only six phosphonate (or phosphate/phosphinate) prodrugs have reached clinical use to our knowledge, including the aryl phosphoramidates sofosbuvir for hepatitis C and remdesivir for COVID-19.24 Application of the aryl amidate strategy (e.g. 6) 25–26 or the related aryl pivaloyloxymethyl strategy (e.g. 7)23, 27–29 to phosphoantigens, also is promising. At the same time, the compounds of these series require synthetic approaches that may be difficult to scale and require identification and separation of phosphorus stereoisomers26 in compounds that may be difficult to crystalize. Bis-amidate prodrug forms have been proposed by others to avoid issues of phosphorus stereochemistry and release prodrug fragments that are naturally occurring and nontoxic amino acids. 30–37 However, until now the bis-amidate approach has not been applied to phosphoantigens. In the present study, we report the synthesis of a panel of bis-amidate analogs of C-HMBP, evaluate their ability to function as phosphoantigen prodrugs, and compare the kinetics of activation to those of other prodrug forms delivering the same payload.

Synthesis of the C-HMBP bis-amidates began with the previously reported phosphonate dimethyl ester 9 (Scheme 1).20 Treatment of compound 9 with excess trimethylsilyl bromide in pyridine provided the bis-trimethylsilyl phosphonate 10, which could be used in the next transformation without isolation. This intermediate was coupled to five selected amino acid hydrochloride salts in the presence of triphenylphosphine, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, and pyridine to afford the five corresponding bis-amidates 11-15, which can be viewed as synthetic analogs of DMAPP (3).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of bis-amidates 11-17.

Reagents and conditions: a) TMSBr, pyridine, 0 °C to RT, overnight; b) amino acid ester hydrochloride salt, PPh3, 2,2′-dithiodipyridine, pyridine, 60 °C, overnight; c) SeO2, 70% aqueous t-BuOOH, pyridine, methanol, 0 °C to RT, overnight.

The C-DMAP bis-amidates 11-15 were evaluated for their stability in plasma and K562 lysate (Table 1).38–40 The positive control, bis-POM compound 5, previously was established to have low plasma stability with 95% metabolized by 24 hours in plasma, while the control compound aryl amidate 6 was previously established to have strong plasma stability with 95% remaining after 24 hours.25 In initial studies, compound 15 was difficult to dissolve and manipulate, likely due to its hydrophobicity, so it was excluded from further studies. In plasma, compounds 11-14 were generally stable as at least 70% of each compound remained after 24-hour exposure, corresponding to plasma half-lives of over 24 hours for each compound. Compound 12 was the least plasma stable of the group, but at least 70% remained after 24 hours in plasma.

Table 1.

Stability in 50% plasma in phosphate buffered saline and in 5 mg/mL K562 extract in lysis buffer (n=2).

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | Plasma (24 h, percent remaining) | K562 extract (4 h, percent remaining) | |

| 5 | OH | O-POM | O-POM | <525 | 0 +/− 0 |

| 6 | OH | O-Phe | NH-Gly-Et | 9525 | 86 +/− 8 |

| 11 | H | NH-Gly-Et | NH-Gly-Et | 82 +/− 0 | 86 +/− 4 |

| 12 | H | NH-Ala-Et | NH-Ala-Et | 70 +/− 3 | 31 +/− 24 |

| 13 | H | NH-Ala-iPr | NH-Ala-iPr | 90 +/− 8 | 79 +/− 7 |

| 14 | H | NH-Val-Me | NH-Val-Me | 99 +/− 10 | 85 +/− 5 |

| 16 | OH | NH-Gly-Et | NH-Gly-Et | 82 +/− 21 | 57 +/− 13 |

| 17 | OH | NH-Val-Me | NH-Val-Me | 86 +/− 4 | 74 +/− 0 |

In K562 cell extract, the compounds ranged from 31% to 86% remaining after 4 hours. Again, the bis-Ala-Et compound 12 was the most rapidly metabolized while the bis-Gly-Et 11 was the slowest. As a class, the initial activation of the bis-amidates was quicker in K562 lysate compared to aryl amidate 6, for which 86% was remaining after 4 hours. As a class, they were clearly more slowly metabolized relative to the bis-POM analog 5, which totally disappeared during a 4-hour incubation in K562 lysate.

Based on this metabolic data, the bis-Gly-Et (11) and bis-Val-Me (14) compounds were selected for further elaboration to the active C-HMBP payload40–41 for cellular antigenicity experiments. Treatment of the C-DMAP bis-amidates 11 and 14 with a catalytic amount of selenium dioxide and t-butyl hydroperoxide afforded C-HMBP bis-amidates 16 and 17, respectively (Scheme 1). These C-HMBP bis-amidates showed stability in plasma and K562 lysate that was similar to that of the four C-DMAP analogs (Table 1) and therefore they were advanced to cellular testing.

To evaluate the potential of C-HMBP bis-amidates to stimulate proliferation of primary human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells from peripheral blood, compounds 16 and 17 were studied. Both compounds stimulated Vγ9Vδ2 T cell proliferation with similar potency (Table 2). The bis-amidate derived from the L-valine methyl ester 14, compound 17, which had an EC50 of 30 nM, was slightly more active than the glycine-derived compound 16 which had an EC50 of 43 nM. These bis-amidates were 93- and 130-fold more potent than the compound in its free acid form, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the bis-amidate prodrug strategy. This finding suggests that in primary human blood cells bis-amidate prodrugs are functional. However, they are less effective in this assay relative to other prodrug forms that we have evaluated (5–7). 20, 25–28

Table 2.

cLogP values and activity of test compounds for stimulation of human γδ T cell proliferation (n=3).

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cLogP | R1 | R2 | R3 | Proliferation EC50 μM (95% CI) | Fold increase versus sodium salt | |

| 5 | 3.42 | OH | O-POM | O-POM | 0.005420 | 740x |

| 6 | 2.05 | OH | O-Phe | NH-Gly-Et | 0.0003625 | 11,000x |

| 7 | 3.56 | OH | O-Phe | O-POM | 0.01427 | 290x |

| 16 | 0.39 | OH | NH-Gly-Et | NH-Gly-Et | 0.043 (0.016 to 0.12) | 93x |

| 17 | 1.86 | OH | NH-Val-Me | NH-Val-Me | 0.030 (0.012 to 0.078) | 130x |

The novel bis-amidates were next evaluated for their ability to trigger an anti-cancer immune response of the Vγ9Vδ2 T cells against K562 leukemia cells (Table 3). As a control, the compounds first were evaluated for direct toxicity against the K562 cells. Both compounds only mildly inhibited K562 cell growth, and only at concentrations above 10 µM after a 72-hour incubation. These compounds were then tested for the ability to stimulate Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to produce interferon γ after exposure to loaded K562 cells. The K562 cells were exposed to the compounds for various times, washed, then co-cultured with Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Both compounds showed dose- and time-dependent stimulation of interferon γ production (Figure 2). Their potency in this assay fell into the mid-micromolar range and was significantly higher than the comparison compounds. Clearly, during limited exposure times to K562 cells the ester prodrugs are most potent, the bis-amidate prodrugs are the least potent, and the aryl amidate prodrugs have intermediate potency (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicity of compounds toward K562 cells and ability of compound-loaded K562 cells to stimulate human γδ T cell cytokine production (n=3). Values for control compounds.23

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | Toxicity IC50 μM | ELISA EC50 μM (95% CI) 15 min |

ELISA EC50 μM (95% CI) 60 min |

ELISA EC50 μM (95% CI) 240 min |

|

| 5 | OH | O-POM | O-POM | >100 | 0.043 | 0.030 | 0.024 |

| 6 | OH | O-Phe | NH-Gly-Et | >100 | 1.5 | 0.23 | 0.051 |

| 7 | OH | O-Phe | O-POM | >100 | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.0084 |

| 16 | OH | NH-Gly-Et | NH-Gly-Et | 10-100 | 23 (16 to 32) | 7.2 (5.5 to 9.5) | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.3) |

| 17 | OH | NH-Val-Me | NH-Val-Me | 10-100 | 14 (13 to 15) | 5.7 (5.4 to 6.1) | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.0) |

Figure 2. Stimulation of human γδ T cell cytokine production by compound-loaded K562 cells.

K562 cells were loaded with test compounds 16 and 17, washed, then exposed to γδ T cells. The amount of interferon γ produced by the T cells was quantified by ELISA (n=3).

In this study, a small series of bis-amidate prodrugs of ligands for BTN3A1 was synthesized and evaluated. The six bis-amidate prodrugs tested were found to have excellent plasma stability. Two bis-amidate prodrugs that contained an allylic alcohol showed increased activity in 72-hour assays of Vγ9Vδ2 expansion from PBMCs relative to the free phosphonic acid, indicating that they are valid prodrug forms. The bis-amidate prodrugs also stimulated production of interferon γ by Vγ9Vδ2 T cells upon exposure to loaded K562 cells.

Clearly the bis-amidates can be chemically synthesized in a straightforward manner that sidesteps any concern of phosphorus stereochemistry. The synthesis can be readily adapted to different amino acid protecting groups with good yields. On the other hand, conversion of the inactive C-DMAP analogs to the active C-HMBP analogs requires a low yielding selenium dioxide reaction and suffers from difficulty in separating the desired alcohol from the starting material and other oxidation products. This may benefit from a modified synthetic route which installs the alcohol in its acetate form at an earlier stage.29

The metabolism profile of bis-amidate prodrugs has been viewed as attractive due to their ability to release only the intended payload along with nontoxic amino acid byproducts, while at the same time providing enough stability to allow for oral administration.37 Results in our metabolism studies in plasma and K562 cell lysate were promising in that regard, with excellent plasma stability observed with all six of the tested bis-amidates, and K562 metabolism similar to that of the known aryl amidate 6.25 It is possible that the initial step of metabolism, hydrolysis of the amino acid ester, occurs similarly in bis-amidates and aryl-amidates, which would be consistent with our K562 lysate data and a prior bis-amidate study.34 Intriguingly, other bis-amidates have shown pH stability profiles consistent with oral dosing and displayed human serum stability for periods of hours appropriate for human dosing.31 Likewise, some bis-amidates have been reported to show improved Caco-2 permeability relative to bis-acyloxyalkyl prodrug forms, suggesting better bioavailability after oral administration.35 We could hypothesize that bis-amidates of C-HMBP may offer similarly attractive stability profiles appropriate for oral dosing.

In the PBMC Vγ9Vδ2 T cell proliferation assay, the bis-amidates were able to increase the potency of the payload by 93- to 130-fold relative to the corresponding salts. While this is promising in its own regard, these forms were not as effective as other prodrug forms in this assay.23 Because the cLogP values of compounds 6 and 16 are quite similar, it is unlikely that the 100-fold difference in activity of these compounds results from differences in diffusion into the cells. It is more likely that differences in metabolism and drug release underlie this SAR. Because these assays were performed in primary blood cells, they also have implications for other payloads that might target these cells with bis-amidates. While it is possible that these bis-amidates applied to a different payload may experience a different rate of metabolism, the small size of the phosphoantigen payload may mean that it less likely to negatively impact metabolic rate.

An advantage of this approach is the ability to compare the kinetics of activation of various prodrug forms using dose- and time- response data in ELISAs. Because the phosphoantigens have a broad selectivity index, we can observe activity without potential complications from toxicity of the prodrug fragments. Because the payload is constant among the different prodrug forms, we can observe differences that are primarily due to rate of metabolic activation. Collectively, we have explored a variety of cell permeable phosphonate analogs,23 including the bis-alkyl ester 5,20 phosphonamidate forms (e.g. 6),25–26 the mixed acyloxy aryl ester (e.g. 7),27–28 and now the bis-amidate forms of C-HMBP. Although all were derived from the parent phosphonate C-HMBP and all prodrug forms increased activity relative to C-HMBP, at least a 500-fold range of activities was observed within the tested prodrug forms. These results suggest that phosphonate analogs enter cells and then undergo subsequent conversion to C-HMBP, but that they may do so with significantly different effectiveness.23 Since both the initial step (amino acid ester hydrolysis) and the final step (hydrolysis of the phosphonamide bonds) are the same in bis-amidates and aryl amidates,42–43 it is likely that the intermediate step involving cleavage of the first amino acid of the bis-amidate occurs more slowly than elimination of the phenyl group from an aryl amidate.

In summary, bis-amidate phosphoantigen prodrugs are effective in increasing the potency of the charged phosphonate payload as an intracellular ligand for BTN3A1, offer a more straightforward and scalable synthetic procedure that does not introduce phosphorus stereochemistry, and have prolonged plasma stability. These benefits may be offset, to a degree, by a slower payload release relative to the aryl phosphonamidates which decreases their potency in the tested cells, including primary blood cells. Nevertheless, the advantages of bis-amidates may outweigh this disadvantage in specific cases where delayed release is preferable, especially because they release only inert amino acid byproducts upon cellular hydrolysis. Though we did not directly assess oral bioavailability, we think it is likely that bis-amidate prodrugs would provide advantages relative to ester forms in this regard, due to their slower rate of metabolism. At present, we are careful to not generalize our findings beyond the study of phosphoantigens. However, there may be value in application of our approach to the study of different payloads as a function of prodrug form to determine more concretely whether the relationships reported here translate more broadly in scope. We speculate that because the phosphoantigens are relatively small, they may contribute less impact to enzymatic cleavage of the phosphonate prodrug groups and, as a result, other payloads may be less efficiently metabolized. Additional studies are needed to clarify this issue. Furthermore, release of the payload from the bis-amidates studied here supports investigation of prodrug forms bearing larger peptides, perhaps including those directed towards specific peptide transporters.44

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Dr. Jeremy Balsbaugh and the University of Connecticut Proteomics & Metabolomics Facility with the LMCS analysis and Dr. Wu He and the University of Connecticut Flow Cytometry Facility with the cytometry. Research reported in this publication was supported by a Research Program of Excellence Award from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust (D.F.W., P.I.), the National Cancer Institute of the United States National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01CA186935 and R01AI150869 (A.J.W., P.I.), and a grant from the Herman Frasch Foundation for Chemical Research (HF17) (A.J.W., P.I.).

Abbreviations Used

- BTN

butyrophilin

- HMBPP

(E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl diphosphate

- IPP

isopentenyl diphosphate

- DMAPP

dimethylallyl diphosphate

- POM

pivaloyloxymethyl

- pAg

phosphoantigen

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- TCR

T cell receptor

Footnotes

A.J.W. and D. F. W. own shares in Terpenoid Therapeutics, Inc. The current work did not involve the company. The other authors have nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Ebetino FH; Hogan AM; Sun S; Tsoumpra MK; Duan X; Triffitt JT; Kwaasi AA; Dunford JE; Barnett BL; Oppermann U; Lundy MW; Boyde A; Kashemirov BA; McKenna CE; Russell RG, The relationship between the chemistry and biological activity of the bisphosphonates. Bone 2011, 49 (1), 20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Prodrugs of phosphonates and phosphates: crossing the membrane barrier. Top. Curr. Chem 2015, 360, 115–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansa P; Baszczynski O; Dracinsky M; Votruba I; Zidek Z; Bahador G; Stepan G; Cihlar T; Mackman R; Holy A; Janeba Z, A novel and efficient one-pot synthesis of symmetrical diamide (bis-amidate) prodrugs of acyclic nucleoside phosphonates and evaluation of their biological activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2011, 46 (9), 3748–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cesnek M; Jansa P; Smidkova M; Mertlikova-Kaiserova H; Dracinsky M; Brust TF; Pavek P; Trejtnar F; Watts VJ; Janeba Z, Bisamidate Prodrugs of 2-Substituted 9-[2-(Phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]adenine (PMEA, adefovir) as Selective Inhibitors of Adenylate Cyclase Toxin from Bordetella pertussis. ChemMedChem 2015, 10 (8), 1351–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houot R; Schultz LM; Marabelle A; Kohrt H, T-cell-based Immunotherapy: Adoptive Cell Transfer and Checkpoint Inhibition. Cancer immunology research 2015, 3 (10), 1115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sebestyen Z; Prinz I; Dechanet-Merville J; Silva-Santos B; Kuball J, Translating gammadelta (gammadelta) T cells and their receptors into cancer cell therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2020, 19 (3), 169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rigau M; Uldrich AP; Behren A, Targeting butyrophilins for cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol 2021, 42 (8), 670–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribot JC; Lopes N; Silva-Santos B, γδ T cells in tissue physiology and surveillance. Nature Reviews Immunology 2021, 21 (4), 221–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmen Olofsson G; Idorn M; Carnaz Simões AM; Aehnlich P; Skadborg SK; Noessner E; Debets R; Moser B; Met Ö; thor Straten P, Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells Concurrently Kill Cancer Cells and Cross-Present Tumor Antigens. Front. Immunol 2021, 12 (2048). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foord E; Arruda LCM; Gaballa A; Klynning C; Uhlin M, Characterization of ascites- and tumor-infiltrating γδ T cells reveals distinct repertoires and a beneficial role in ovarian cancer. Sci. Transl. Med 2021, 13 (577), eabb0192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morita CT; Jin C; Sarikonda G; Wang H, Nonpeptide antigens, presentation mechanisms, and immunological memory of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells: discriminating friend from foe through the recognition of prenyl pyrophosphate antigens. Immunol. Rev 2007, 215, 59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harly C; Guillaume Y; Nedellec S; Peigne CM; Monkkonen H; Monkkonen J; Li JQ; Kuball J; Adams EJ; Netzer S; Dechanet-Merville J; Leger A; Herrmann T; Breathnach R; Olive D; Bonneville M; Scotet E, Key implication of CD277/butyrophilin-3 (BTN3A) in cellular stress sensing by a major human gamma delta T-cell subset. Blood 2012, 120 (11), 2269–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riano F; Karunakaran MM; Starick L; Li JQ; Scholz CJ; Kunzmann V; Olive D; Amslinger S; Herrmann T, V gamma 9V delta 2 TCR-activation by phosphorylated antigens requires butyrophilin 3 A1 (BTN3A1) and additional genes on human chromosome 6. Eur J Immunol 2014, 44 (9), 2571–2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiemer AJ, Structure-Activity Relationships of Butyrophilin 3 Ligands. ChemMedChem 2020, 15 (12), 1030–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laplagne C; Ligat L; Foote J; Lopez F; Fournie JJ; Laurent C; Valitutti S; Poupot M, Self-activation of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells by exogenous phosphoantigens involves TCR and butyrophilins. Cell. Mol. Immunol 2021, 18 (8), 1861–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boedec A; Sicard H; Dessolin J; Herbette G; Ingoure S; Raymond C; Belmant C; Kraus JL, Synthesis and biological activity of phosphonate analogues and geometric isomers of the highly potent phosphoantigen (E)-1-hydroxy-2-methylbut-2-enyl 4-diphosphate. J. Med. Chem 2008, 51 (6), 1747–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsiao CC; Nguyen K; Jin Y; Vinogradova O; Wiemer AJ, Ligand-induced interactions between butyrophilin 2A1 and 3A1 internal domains in the HMBPP receptor complex. Cell Chem Biol 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyborova A; Beringer DX; Fasci D; Karaiskaki F; van Diest E; Kramer L; de Haas A; Sanders J; Janssen A; Straetemans T; Olive D; Leusen J; Boutin L; Nedellec S; Schwartz SL; Wester MJ; Lidke KA; Scotet E; Lidke DS; Heck AJ; Sebestyen Z; Kuball J, γ9δ2T cell diversity and the receptor interface with tumor cells. J. Clin. Invest 2020, 130 (9), 4637–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandstrom A; Peigne CM; Leger A; Crooks JE; Konczak F; Gesnel MC; Breathnach R; Bonneville M; Scotet E; Adams EJ, The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Immunity 2014, 40 (4), 490–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsiao CH; Lin X; Barney RJ; Shippy RR; Li J; Vinogradova O; Wiemer DF; Wiemer AJ, Synthesis of a phosphoantigen prodrug that potently activates Vγ9Vδ2 T-lymphocytes. Chem. Biol 2014, 21 (8), 945–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes DA; Chen HC; Price AJ; Keeble AH; Davey MS; James LC; Eberl M; Trowsdale J, Activation of human γδ T cells by cytosolic interactions of BTN3A1 with soluble phosphoantigens and the cytoskeletal adaptor periplakin. J. Immunol 2015, 194 (5), 2390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilcollins AM; Li J; Hsiao CHC; Wiemer AJ, HMBPP Analog Prodrugs Bypass Energy-Dependent Uptake To Promote Efficient BTN3A1-Mediated Malignant Cell Lysis by V gamma 9V delta 2 T Lymphocyte Effectors. J Immunol 2016, 197 (2), 419–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsiao CC; Wiemer AJ, A power law function describes the time- and dose-dependency of Vγ9Vδ2 T cell activation by phosphoantigens. Biochem. Pharmacol 2018, 158, 298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiemer AJ, Metabolic Efficacy of Phosphate Prodrugs and the Remdesivir Paradigm. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2020, 3 (4), 613–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lentini NA; Foust BJ; Hsiao CC; Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Phosphonamidate Prodrugs of a Butyrophilin Ligand Display Plasma Stability and Potent Vγ9 Vδ2 T Cell Stimulation. J. Med. Chem 2018, 61 (19), 8658–8669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lentini NA; Hsiao CC; Crull GB; Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Synthesis and Bioactivity of the Alanyl Phosphonamidate Stereoisomers Derived from a Butyrophilin Ligand. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2019, 10 (9), 1284–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foust BJ; Poe MM; Lentini NA; Hsiao CC; Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Mixed Aryl Phosphonate Prodrugs of a Butyrophilin Ligand. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 8 (9), 914–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foust BJ; Li J; Hsiao CC; Wiemer DF; Wiemer AJ, Stability and Efficiency of Mixed Aryl Phosphonate Prodrugs. ChemMedChem 2019, 14 (17), 1597–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harmon NM; Huang X; Schladetsch MA; Hsiao CC; Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Potent double prodrug forms of synthetic phosphoantigens. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2020, 28 (19), 115666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolfgang GH; Shibata R; Wang J; Ray AS; Wu S; Doerrfler E; Reiser H; Lee WA; Birkus G; Christensen ND; Andrei G; Snoeck R, GS-9191 is a novel topical prodrug of the nucleotide analog 9-(2-phosphonylmethoxyethyl)guanine with antiproliferative activity and possible utility in the treatment of human papillomavirus lesions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2009, 53 (7), 2777–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuigan C; Madela K; Aljarah M; Bourdin C; Arrica M; Barrett E; Jones S; Kolykhalov A; Bleiman B; Bryant KD; Ganguly B; Gorovits E; Henson G; Hunley D; Hutchins J; Muhammad J; Obikhod A; Patti J; Walters CR; Wang J; Vernachio J; Ramamurty CV; Battina SK; Chamberlain S, Phosphorodiamidates as a promising new phosphate prodrug motif for antiviral drug discovery: application to anti-HCV agents. J. Med. Chem 2011, 54 (24), 8632–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu X; Jiang S; Li C; Xin J; Yang Y; Ji R, Design and synthesis of novel bis(L-amino acid) ester prodrugs of 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]adenine (PMEA) with improved anti-HBV activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2007, 17 (2), 465–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu XZ; Ou Y; Pei JY; Liu Y; Li J; Zhou W; Lan YY; Wang AM; Wang YL, Synthesis, anti-HBV activity and renal cell toxicity evaluation of mixed phosphonate prodrugs of adefovir. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2012, 49, 211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubota K; Inaba S; Nakano R; Watanabe M; Sakurai H; Fukushima Y; Ichikawa K; Takahashi T; Izumi T; Shinagawa A, Identification of activating enzymes of a novel FBPase inhibitor prodrug, CS-917. Pharmacology research & perspectives 2015, 3 (3), e00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Šmídková M; Dvoráková A; Tloust’ová E; Česnek M; Janeba Z; Mertlíková-Kaiserová H, Amidate prodrugs of 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]adenine as inhibitors of adenylate cyclase toxin from Bordetella pertussis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 2014, 58 (2), 664–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Česnek M; Šafránek M; Dračínský M; Tloušťová E; Mertlíková-Kaiserová H; Hayes MP; Watts VJ; Janeba Z, Halogen-Dance-Based Synthesis of Phosphonomethoxyethyl (PME) Substituted 2-Aminothiazoles as Potent Inhibitors of Bacterial Adenylate Cyclases. ChemMedChem 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dang Q; Kasibhatla SR; Reddy KR; Jiang T; Reddy MR; Potter SC; Fujitaki JM; van Poelje PD; Huang J; Lipscomb WN; Erion MD, Discovery of potent and specific fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase inhibitors and a series of orally-bioavailable phosphoramidase-sensitive prodrugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129 (50), 15491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joachimiak L; Janczewski L; Ciekot J; Boratynski J; Blazewska K, Applying the prodrug strategy to alpha-phosphonocarboxylate inhibitors of Rab GGTase - synthesis and stability studies. Org. Biomol. Chem 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong H; Kuder CH; Wasko BM; Hohl RJ, Quantitative determination of isopentenyl diphosphate in cultured mammalian cells. Anal. Biochem 2013, 433 (1), 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harmon NM; Poe MM; Huang X; Singh R; Foust BJ; Hsiao CC; Wiemer DF; Wiemer AJ, Synthesis and Metabolism of BTN3A1 Ligands: Studies on Diene Modifications to the Phosphoantigen Scaffold. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2022, 13 (2), 164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lentini NA; Schroeder CM; Harmon NM; Huang X; Schladetsch MA; Foust BJ; Poe MM; Hsiao CC; Wiemer AJ; Wiemer DF, Synthesis and Metabolism of BTN3A1 Ligands: Studies on Modifications of the Allylic Alcohol. ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2021, 12 (1), 136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birkus G; Kutty N; He GX; Mulato A; Lee W; McDermott M; Cihlar T, Activation of 9-[(R)-2-[[(S)-[[(S)-1-(Isopropoxycarbonyl)ethyl]amino] phenoxyphosphinyl]-methoxy]propyl]adenine (GS-7340) and other tenofovir phosphonoamidate prodrugs by human proteases. Mol. Pharmacol 2008, 74 (1), 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freel Meyers CL; Borch RF, Activation mechanisms of nucleoside phosphoramidate prodrugs. J. Med. Chem 2000, 43 (22), 4319–4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandsch M; Knütter I; Bosse-Doenecke E, Pharmaceutical and pharmacological importance of peptide transporters†. J. Pharm. Pharmacol 2008, 60 (5), 543–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.