Abstract

Objective

To develop a new method for reliable and rapid determination of the fitness of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.

Methods

Competition experiments between two SARS-CoV-2 variants were performed in cells of the upper (nasal human airway epithelium) and lower (Calu-3 cells) respiratory tracts followed by quantification of variant ratios by droplet digital reverse transcription (ddRT)-PCR.

Results

In competition experiments, the delta variant outcompeted the alpha variant in both cells of the upper and lower respiratory tracts. A 50/50% mixture of delta and omicron variants indicated a predominance of omicron in the upper respiratory tract whereas delta predominated in the lower respiratory tract. There was no evidence of recombination events between variants in competition as assessed by whole gene sequencing.

Conclusion

Differential replication kinetics were shown between variants of concern which may explain, at least partly, the emergence and disease severity associated with new SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2; Variants, Competition; Fitness; droplet digital RT-PCR

1. Introduction

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in China at the end of 2019, numerous variants of concern (VOCs) have been described. These variants harbor several mutations mainly located in the spike (S) gene, in particular within the receptor-binding domain (RBD). During the late winter of 2020, the initial B.1 lineage was supplanted by the alpha variant (B.1.1.7) which remained dominant until the fall of 2021 when it was replaced by the delta variant (B.1.617.2). At the end of 2021, the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant rapidly disseminated and replaced the delta variant. Subsequently, different sub-lineages of omicron virus predominated.

These VOCs were associated with higher transmissibility, ability to evade neutralizing antibodies induced by vaccination or infection and, in some cases, by increased disease severity [1,2]. These features may be related to improved replication capacity of the newer variants and/or the absence of protective host immunity. In this study, we evaluated the replication kinetics of some major VOCs that circulated in the Province of Quebec, Canada, by performing competition experiments in continuous lung cells (Calu-3) and reconstituted nasal human airway epithelium (HAE). We developed a rapid droplet digital reverse transcription-PCR (ddRT-PCR) method to assess the proportions of variants and compared it to variant frequencies determined by whole genome sequencing (WGS).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and viruses

The VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cell line was provided by the NIBSC Research Reagent Repository, UK, with thanks to Dr. Makoto Takeda. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 1% HEPES and 1 mg/mL geneticin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The immortalized Calu-3 cell line was obtained from Dr. Andres Finzi at University of Montréal. VeroE6 (green monkey kidney) cells (American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) no. CRL-1586; Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in minimum essential medium (MEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen) and 1% HEPES. Nasal HAE (MucilAir™; pool of 14 donors, catalog no. EP02MP) and culture medium were provided by Epithelix Sàrl (Geneva, Switzerland). Epithelial cells were cultured for 45 days to reconstitute fully differentiated nasal HAE composed of ciliated, goblet and basal primary cells. Nasal HAE was cultured in 24-well inserts at the air-liquid interface at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The medium at the basal pole of nasal HAE was replaced by fresh medium every 48 h during culture maintenance and experimental protocols.

SARS-CoV-2 strains Quebec/CHUL/76,710 (delta: B.1.617.2, sub-lineage AY.103) and Quebec/CHUL/904,274 (omicron: B.1.1.529, sub-lineage BA.1.15) were isolated from nasopharyngeal swabs of patients in Quebec City, Canada, in November 2021 and December 2021, respectively. The alpha variant was provided by the Quebec Public Health Laboratory from a clinical sample obtained in March 2021. Viral spike genes were sequenced by Sanger using the ABI 3730xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

The strains were passaged twice on VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells except the alpha variant that was passaged once on VeroE6 and then once on VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells. Viral titers were quantified by plaque assays performed on VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells. All experimental work using infectious SARS-CoV-2 variant was performed in a Biosafety Level 3 (BSL3) facility at the CHU de Québec-Université Laval.

2.2. Competition experiments

Before each infection, apical poles of nasal HAE were gently washed once with 200 μL of pre-warm Opti-MEM (Gibco; ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Calu-3 cells were gently washed with pre-warm PBS. Nasal HAE and Calu-3 cells were then infected at a MOI of 0.01 with pure viral population (100%) as well as 50:50% mixtures (alpha:delta / delta:omicron) based on PFU numbers. After an adsorption period of 1 h, the inoculum was removed. Nasal HAEs were cultured at the air-liquid interface whereas fresh medium (MEM 1X with 1% HEPES) was added on Calu-3 cells. For all experimental conditions, viral production was evaluated from apical washes with 200 μL of pre-warm Opti-MEM for 10 min at 37 °C, under 5% CO2 (nasal HAE) or from supernatants (Calu-3) at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h post-infection. Apical washes and supernatants were quantified by ddRT-PCR for variant sub-populations. Competition experiments were performed twice in quadruplicate.

2.3. ddRT-PCR assay

The ddRT-PCR tests were designed as previously reported [3,4] to determine variants ratios in samples collected from Calu-3 supernatants and nasal HAE apical pole washes. Viral RNA was extracted using the MagNA Pure LC instrument (Total nucleic acid isolation kit; Roche Molecular System, Laval, QC, Canada). The workflow and data analyses were performed with the One-Step ddRT-PCR supermix according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers and probes (available upon request) were designed to target the spike N501Y substitution present in alpha and omicron variants but not in the delta variant. The cycled plate was read in the FAM and HEX channels of the QX200 reader (Bio-Rad, Montreal, Quebec, Canada).

2.4. Whole genome sequencing and sequence data analysis

Viral RNA was sequenced with the Illumina technology. A targeted SARS-CoV-2 amplification strategy was used based on the ARTIC V4.1 primer scheme [5] and libraries were prepared with Illumina COVIDSeq Test kit [6]. Data analysis was performed using the GenPipes Covseq pipeline [7] to perform alignment and produce variant calls. Briefly, host reads were removed by aligning to a hybrid reference with both human (GRCh38) and the Wuhan-Hu-1 SARS-CoV-2 reference (MN908947.3). Raw reads were first trimmed using cutadapt (v2.10), then aligned to the reference using bwa-mem (v0.7.17) [8]. Aligned reads were filtered using sambamba (v0.7.0) [9] to remove paired reads with an insert size outside the 60–300 bp range, unmapped reads, and all secondary alignments. Then, any remaining ARTIC primers (v4.1) were trimmed with iVar (v1.3) [10]. To create a consensus sequence of SARS-CoV-2 for a sample, a pileup was produced using Samtools (v1.12) [11] which was used as an input for FreeBayes (v1.3.4) [12]. Mutations were annotated with snpEff (v4.5) [13]. Single nucleotide variants below 5% allele frequency were filtered out. Variable positions were manually reviewed with Integrative Genome Viewer (version 2.11.0) [14]. Variant classification was performed with Pangolin program (v4.2, UShER analysis mode) [15], and a list of characteristic mutations of each lineage was used to estimate the proportion of each variant in the competition experiment. The program ncov-recombinant (v.0.6.0) was used to detect any signs of recombination between the variants in competition [16]. WGS was done on the 96 hour post-infection time point only.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Viral RNA copy numbers were compared two by two using the Mann-Whitney test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0.

3. Results

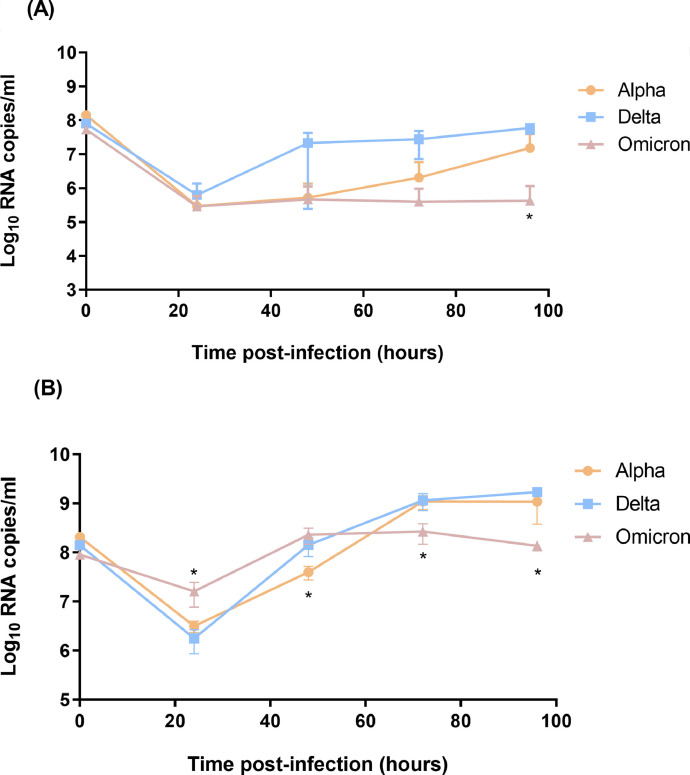

Single virus replication kinetics were first evaluated over 96 h by ddRT-PCR in the two cell systems. In Calu-3 cells, the omicron variant had significantly reduced viral load compared to the alpha and delta variants at 96 h (Fig. 1 A). In nasal HAE, the omicron viral load was significantly higher than those of the alpha and delta variants at 24 h but it was significantly reduced at later time points (72 h and 96 h) compared to the other two viruses (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

In vitro replication kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Calu-3 cells (A) and nasal HAE (B). Nasal HAE and Calu-3 cells were infected with viruses at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Supernatants and apical washes were harvested at the indicated time points before viral load quantification by ddRT-PCR. Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney test. *, p < 0.05. Data are from one experiment performed in quadruplicate.

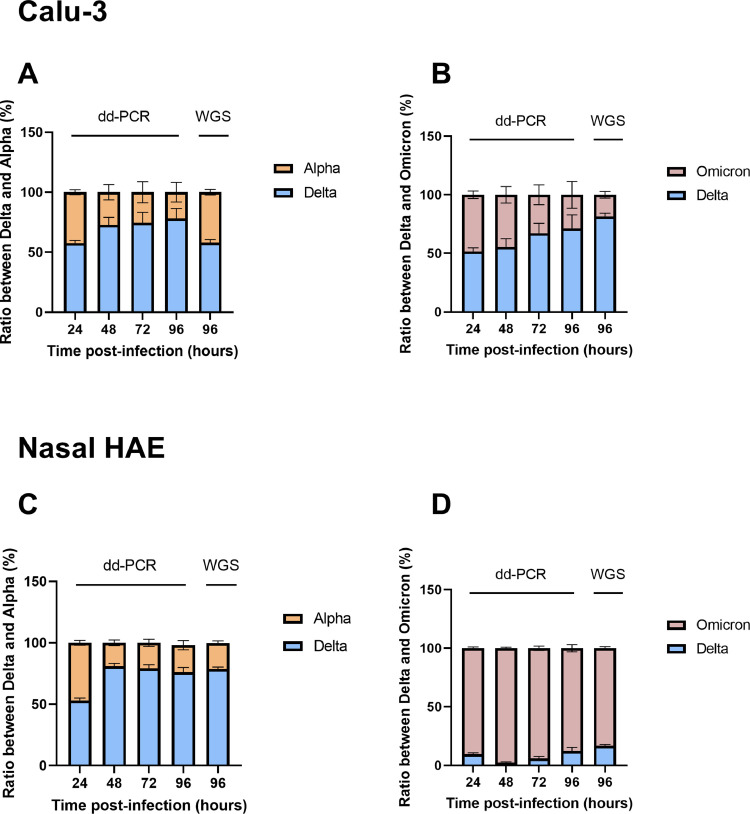

Competition experiments using 50–50% ratios of two viruses (based on PFU counts) performed in Calu-3 cells revealed a progressive replication advantage over time for delta over alpha and for delta over omicron when reporting normalized viral load ratios (Fig. 2 A, B). In nasal HAE, there was a replication advantage for delta over alpha and a rapid with almost complete predominance of omicron over delta (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

In vitro quantification of variant sub-populations in the competition experiments. (A) Calu-3 cells: alpha versus delta; (B) Calu-3 cells: delta versus omicron; (C) Nasal HAE: alpha versus delta; (D) Nasal HAE: delta versus omicron. Proportions of variants were derived from a 50:50% mixture based on PFU counts. Cells were infected with each virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.01. Proportions of each viral population were determined by ddRT-PCR or WGS (96 h only) and normalized as 50%−50% ratio at time 0. Proportions are expressed as a percentage of the total viral population. Mean proportion values from two independent experiments performed in quadruplicate are shown. Note: HAE, human airway epithelium; WGS, whole genome sequencing.

Variant frequencies, as determined by allele frequencies characteristic of each variant and detected by WGS, were very similar to the results obtained by ddRT-PCR based on substitution N501Y at 96 h and showed the same trends. Finally, there was no sign of recombination events between the different variants in competition using the ncov-recombinant software.

4. Discussion

We report differential replication kinetics of some SARS-CoV-2 VOCs using competition experiments and a novel ddRT-PCR methodology based on the presence or absence of the spike N501Y substitution. More specifically, we showed the predominance of delta (AY.103) over alpha (B.1.1.7) variant in cells from both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. As for the competition between delta (AY.103) and omicron (BA.1.15), we found that the former variant predominated over time in pulmonary cells whereas omicron rapidly and almost completely replaced delta in nasal HAEs.

There have been conflicting data regarding the fitness advantage of the alpha variant compared to the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain depending on the type of cells and animal models [17,18]. Competition between these two viruses was not evaluated in our study.

Regarding the relative fitness between alpha and delta variants, our results showing the predominance of the delta variant in both nasal HAE and Calu-3 cells are in agreement with previous data, which contributed to the replacement of the alpha by the delta variant in humans [19]. It was shown that the delta spike P681R substitution enhanced the cleavage of full-length spike to S1 and S2 [19].

The omicron variant replaced the delta virus during the winter of 2022 in North America. The former variant showed increased transmission in humans and had 37 amino acid substitutions in the spike protein, 15 of which in the receptor-binding domain. It is still unclear whether the exceptional transmissibility of omicron is due to immune evasion mechanisms and/or intrinsic virological properties. In line with a less severe disease phenotype compared to the other VOCs [1,2], we showed that omicron replicated more rapidly (at 24 h) than the previous variants in nasal epithelium but replicated less efficiently in lung cells (Fig. 1) as reported by others [20], [21], [22]. In competition experiments (Fig. 2), we showed the predominance of delta over omicron in the lower respiratory tract but the opposite was found in the epithelium of the upper respiratory tract. Mechanistically, omicron shows a preference for the endosomal route of entry compared to the TMPRSS2 route with the former route being more restricted in Calu-3 cells [20,22].

A strength of our study is the development of a rapid and reproducible ddRT-PCR assay for estimating the evolution of viral mixtures over time. Indeed the variant ratios obtained by ddRT-PCR were in line with those estimated by WGS at 96 h (Fig. 2). Among the limitations of our study are the small number of competition experiments and the absence of confirmatory animal studies. In addition, we didn't use primary cells for replication in the lower respiratory tract. Obviously, we couldn't perform competition between alpha and omicron variants because they both have the same N501Y substitution in the spike protein.

In conclusion, we describe a simple method composed of competition experiments in cell lines of the upper and lower respiratory tracts followed by quantification using ddRT-PCR to rapidly assess the fitness of new VOCs.

Funding

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to GB)

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Esper F.P., Adhikari T.M., Tu Z.J., Cheng Y.W., El-Haddad K., Farkas D.H., et al. Alpha to omicron: disease severity and clinical outcomes of major SARS-CoV-2 variants. J. Infect. Dis. 2023;227:344–352. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trobajo-Sanmartn C., Miqueleiz A., Guevara M., Fernndez-Huerta M., Burgui C., Casado I., et al. Comparison of the risk of hospitalization and severe disease among co-circulating severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 variants. J. Infect. Dis. 2023;227:332–338. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Checkmahomed L., M'Hamdi Z., Carbonneau J., Venable M.C., Baz M., Abed Y., et al. Impact of the baloxavir-resistant polymerase acid I38T substitution on the fitness of contemporary influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) strains. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;221:63–70. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor S.C., Carbonneau J., Shelton D.N., Boivin G. Optimization of droplet digital PCR from RNA and DNA extracts with direct comparison to RT-qPCR: clinical implications for quantification of oseltamivir-resistant subpopulations. J. Virol. Methods. 2015;224:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Initial implementation of an ARTIC bioinformatics platform for nanopore sequencing of nCoV2019 novel coronavirus. https://github.com/artic-network/artic-ncov2019, 2023 (accessed March 6, 2023).

- 6.Illumina COVIDSeq test instructions for use. https://support.illumina.com/downloads/illumina-covidseq-test-instructions-for-use-1000000128490.html, 2023 (accessed March 6, 2023).

- 7.CoV Sequencing Pipeline. https://genpipes.readthedocs.io/en/genpipes-v4.1.2/user_guide/pipelines/gp_covseq.html, 2019 (accessed March 6, 2023).

- 8.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarasov A., Vilella A.J., Cuppen E., Nijman I.J., Prins P. Sambamba: fast processing of NGS alignment formats. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2032–2034. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellano S., Cestari F., Faglioni G., Tenedini E., Marino M., Artuso L., et al. iVar, an interpretation-oriented tool to manage the update and revision of variant annotation and classification. Genes (Basel) 2021;12 doi: 10.3390/genes12030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrison E., Marth G. arXiv preprint; 2012. Haplotype-Based Variant Detection from Short-Read Sequencing.https://arxiv.org/abs/1207.3907v2 [q-bio.GN] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.P. Cingolani, A. Platts, L. Wang le, M. Coon, T. Nguyen, L. Wang, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (Austin). 6 (2012) 80–92 https://doi.org/10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Robinson J.T., Thorvaldsdottir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E.S., Getz G., et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Toole A., Scher E., Underwood A., Jackson B., Hill V., McCrone J.T., et al. Assignment of epidemiological lineages in an emerging pandemic using the pangolin tool. Virus Evol. 2021;7:veab064. doi: 10.1093/ve/veab064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ktmeaton/ncov-recombinant. https://github.com/ktmeaton/ncov-recombinant, 2023 (accessed March 6, 2023).

- 17.Ulrich L., Halwe N.J., Taddeo A., Ebert N., Schon J., Devisme C., et al. Enhanced fitness of SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern Alpha but not Beta. Nature. 2022;602:307–313. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04342-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y., Liu J., Plante K.S., Plante J.A., Xie X., Zhang X., et al. The N501Y spike substitution enhances SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission. Nature. 2022;602:294–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04245-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J., Du P., Yang L., Zhang J., Song C., Chen D., et al. Two-step fitness selection for intra-host variations in SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2022;38 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.T.P. Peacock, J.C. Brown, J. Zhou, N. Thakur, K. Sukhova, J. Newman, et al. The Altered Entry Pathway and Antigenic Distance of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant Map to Separate Domains of Spike Protein. bioRxiv preprint https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.31.474653.

- 21.Do T.N.D., Claes S., Schols D., Neyts J., Jochmans D. SARS-CoV-2 virion infectivity and cytokine production in primary human airway epithelial cells. Viruses. 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/v14050951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui K.P.Y., Ho J.C.W., Cheung M.C., Ng K.C., Ching R.H.H., Lai K.L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant replication in human bronchus and lung ex vivo. Nature. 2022;603:715–720. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]