Abstract

Background

Cancer is a complex disease that is the second leading cause of death in the United States. Despite research efforts, the ability to manage cancer and select optimal therapeutic responses for each patient remains elusive. Chromosomal instability (CIN) is primarily a product of segregation errors wherein one or many chromosomes, in part or whole, vary in number. CIN is an enabling characteristic of cancer, contributes to tumor-cell heterogeneity, and plays a crucial role in the multistep tumorigenesis process, especially in tumor growth and initiation and in response to treatment.

Aims

Multiple studies have reported different metrics for analyzing copy number aberrations as surrogates of CIN from DNA copy number variation data. However, these metrics differ in how they are calculated with respect to the type of variation, the magnitude of change, and the inclusion of breakpoints. Here we compared metrics capturing CIN as either numerical aberrations, structural aberrations, or a combination of the two across 33 cancer data sets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

Methods and results

Using CIN inferred by methods in the CINmetrics R package, we evaluated how six copy number CIN surrogates compared across TCGA cohorts by assessing each across tumor types, as well as how they associate with tumor stage, metastasis, and nodal involvement, and with respect to patient sex.

Conclusions

We found that the tumor type impacts how well any two given CIN metrics correlate. While we also identified overlap between metrics regarding their association with clinical characteristics and patient sex, there was not complete agreement between metrics. We identified several cases where only one CIN metric was significantly associated with a clinical characteristic or patient sex for a given tumor type. Therefore, caution should be used when describing CIN based on a given metric or comparing it to other studies.

1. Introduction

Genomic instabilities, molecular signatures of gross genomic alterations, are enabling characteristics of cancer etiology and pathogenesis (1,2). They result in chromosomal breakages and rearrangements that can develop into chromosomal instability (CIN). CIN is primarily caused by defective cell cycle quality control mechanisms, including an elevated rate of segregation errors altering chromosomal content (3), and manifests as either numerical aberrations, structural aberrations, or a combination of the two. Numerical aberrations are whole chromosomal aberrations that lead to the loss of heterozygosity (i.e., where a chromosomal region is lost in one copy for a diploid genome) and variability in gene dosage effects. This can result in a phenotype that is a consequence of chromosome-wide altered expression patterns. Structural aberrations are sub-chromosomal and can lead to the fusion of gene products or amplified and/or deleted genes, specifically impacting the genes of the affected chromosomal regions (3). At the molecular level, CIN has been shown to represent distinct etiologies, promote disease progression, and metastases. It has also been associated with patient prognosis, drug efficacy, and drug resistance across many cancers (4-7). As CIN has been associated with poor patient outcomes in some cancers but improved survival in others (8,9), CIN appears to have cell- and tissue-specific consequences associated with the originating tissue and tumor site (10,11). For example, while CIN has been shown to have a non-monotonic relationship with patient outcome in ER−/ERBB2− breast, gastric, ovarian, squamous non-small cell lung carcinomas (i.e., patients with the lowest or highest quartile of CIN have a significantly improved hazard ratio) (12), it has been associated with poorer prognosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients (13). Therefore, CIN is a promising biomarker of patient prognosis and drug response but requires tissue-specific evaluation.

Several CIN scores have been proposed for analyzing copy number aberrations (i.e., deletions or amplifications of segments of the genome) as surrogates of chromosomal instability. Still, these scores represent various aspects of CIN and have been associated with different clinical and biological phenotypes across several cancer types (14-17). Therefore, assessing copy number aberration CIN surrogates across cancer types and tissue backgrounds is critical to evaluate the role of CIN in cancer etiology and progression. In addition, it enables the comparison of key results across studies and the identification of robust scores for future biomarker development. We recently published an R package, CINmetrics (18), for calculating six different copy number aberration CIN surrogate metrics, and here apply it to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). These metrics include total aberration index (TAI) (14), modified TAI, copy number abnormality (CNA) (15), number of break points (16), altered base segments (17), and fraction genome altered (FGA). Specifically, they differ based on their ability to detect structural, numerical, or whole genome instability (discussed in depth in (18)). In this study, we aim to provide a comprehensive comparison of these metrics across a wide range of cancer types and with respect to clinical characteristics (tumor stage, node, and metastasis) and patient sex. We determine these CIN metric scores across 33 cancers and 22,629 samples from 11,124 patients and provide comparison statistics to evaluate how CIN metric scores vary across and within different cancers based on CIN classification (numerical, structural, or global), clinical characteristics, and patient sex.

2. Methods and Statistical Analysis

We downloaded masked copy number variation (CNV) (Affymetrix SNP 6.0 array) data and associated patient clinical data from all 33 projects in the TCGA portal using the ‘TCGAbiolinks’ R package (2.18.0) (19) in August 2021 using R (Version 4.0.4) and RStudio (Version 1.4.1106) locally and stored within a CSV file. We also downloaded TCGA Level 3, normalized and aggregated RNA-seq count data in November 2021 from all 33 projects in the TCGA portal using the ‘TCGAbiolinks’ R package (Version 2.22.1) using R (Version 4.0.2) and RStudio (Version 1.1.463) with University of Alabama at Birmingham’s High-Performance Computing Cluster, Cheaha. All analyses associated with this paper are on GitHub (https://github.com/lasseignelab/CINmetrics_Cancer_Analysis) and available at https://zenodo.org/record/7942543#.ZGPu8OzMJ4A.

With the CINmetrics R package (Version 0.1.0), we calculated each CIN metric for the 22,629 non-tumor and tumor samples (18). CINmetrics analyzes six different copy number aberration CIN surrogate metrics from masked CNV data as previously described (14-17). The mathematical formulas for those metrics are described in detail in Oza, et al. 2023, but briefly, those metrics are TAI (Total Aberration Index), Modified TAI, CNA (Copy Number Abnormality), Base Segments (i.e., the number of altered bases), Break Points (i.e., the number of break points), and FGA (Fraction of Genome Altered). Each metric defines chromosomal instability (CIN) by calculating numerical and/or structural aberrations as described in Oza et. al. (18) and can be grouped as numerical scores (Base Segments, FGA), structural scores (Break Points and CNA), and overall scores (TAI and Modified TAI). CNA and Break Points both consider the segmental abnormalities of the chromosome, but CNA requires that adjacent segments have a difference in segmentation mean values. TAI and Modified TAI can both be interpreted as the absolute deviation from the normal copy number state averaged over all genomic locations, where Modified TAI removes the directionality aspect of the TAI metric by taking the absolute value of the segment mean.

All cross-sample CIN metrics comparisons using Spearman’s correlation (20) were conducted using the base ‘stats’ R package (21) (Version 4.0.4) ‘cor’ function between the non-tumor (“Blood Derived Normal,” “Solid Tissue Normal,” “Bone Marrow Normal,” and “Buccal Cell Normal”) and tumor (“Metastatic,” “Primary Blood Derived Cancer,” “Primary Tumor,” “Recurrent Tumor,” “Additional - New Primary,” and “Primary Blood Derived Cancer - Peripheral Blood”) samples. All heatmaps were generated using the ‘ComplexHeatmap’ R package (Version 2.9.3) (22) and clustered with the “complete’ method by “Euclidean distance.”

For analyses that compare CIN metrics by clinical characteristics, we used the TNM (tumor stage, node, and metastasis) staging provided by TCGA in the “ajcc_pathologic_m” (except for ACC where we used “ajcc_clinical_m”), “ajcc_pathologic_n,” and “ajcc_pathologic_t” attributes using the ‘GDCquery_clinic’ function. These comparisons were made across the 22 cancer types with corresponding data (i.e., all but Glioblastoma (GBM), Acute myeloid leukemia (LAML), Ovarian cancer (OV), Thymoma (THYM), Uterine carcinoma (UCS), Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC), Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC), Sarcoma (SARC), Prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), and Brain lower grade glioma (LGG)). In addition, we conducted the Mann Whitney Wilcoxon Test (23,24) for comparisons between CIN metrics and the staging variables using the ‘rstatix’ R package (Version 0.7.0) (25) ‘wilcox_test’ function. We used Bonferroni-corrected p-values to account for multiple hypothesis testing, and we considered corrected p-values of less than 0.05 to indicate significant CIN metric scores for the TNM staging analyses.

For analyses comparing CIN metrics by sex for each cancer, we used the ‘gender’ (i.e., biological male or female) information provided by TCGA for each sample. We compared 27 cancer types because TCGA projects OV, PRAD, UCEC, UCS, Testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), Cervical squamous cell carcinoma, and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC) occur predominantly in one biological sex. We conducted a Mann Whitney Wilcoxon test between CIN metrics and the sex variable using the ‘rstatix’ R package (Version 0.7.0) ‘wilcox_test’ function and multiple hypothesis tests corrected using the Bonferroni method. We plotted raincloud plots of these multiple hypothesis corrected p-values by CIN metric using the ggplot2 (Version 3.3.5), ggpubr (Version 0.4.0), PupillometryR (Version 0.0.4), and gghalves (Version 0.1.1) R packages for the top cancer identified by each CIN metric.

3. Results

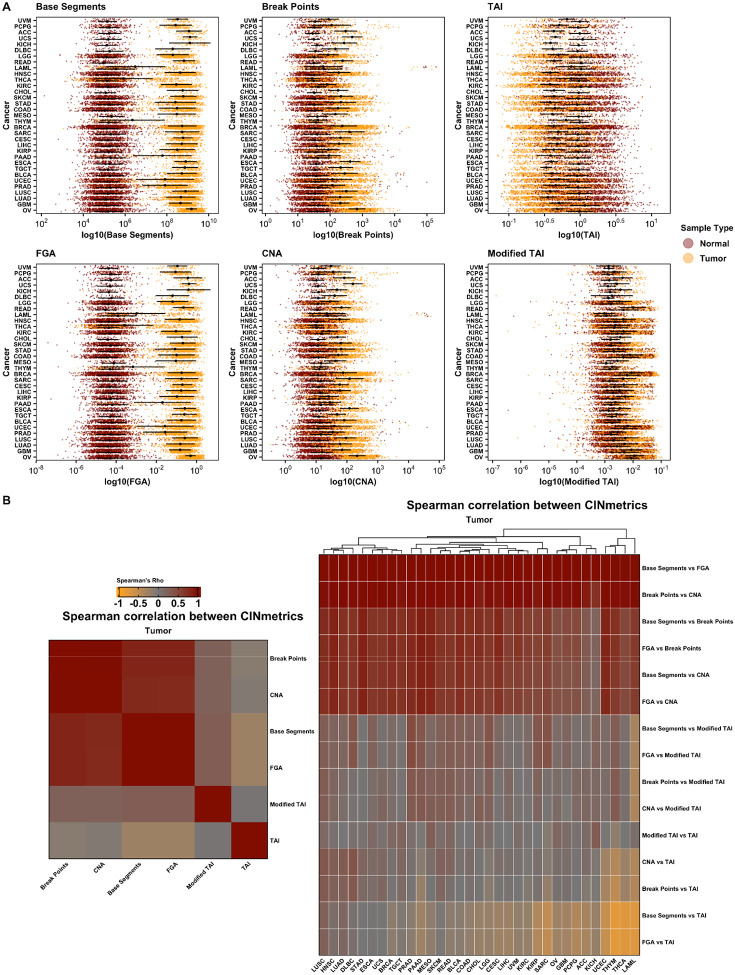

We compiled masked CNV data for 11,124 patients across all TCGA projects (n=33 cancer types, 22,629 samples) and applied the six CIN inference calculations in the CINmetrics R package to each cancer data set (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CIN metrics by cancer type for tumor and matched non-tumor samples (A) and Spearman’s correlation between tumor CIN metrics by cancer type (B). CIN, chromosomal instability.

Figure 1A shows the distribution of CIN scores across normal and tumor samples. Within each CIN "type" - structural (Base Segments, FGA), numerical (CNA, Break Points), or overall (TAI, Modified TAI) - the distribution pattern is consistent. However, there are noticeable differences across these types. For example, structural CIN metrics show a more pronounced distinction between normal and tumor samples compared to numerical CIN metrics. This is likely due to comparative genomic hybridization arrays used in TCGA to measure CNVs which are more biased towards detecting numerical CIN than structural CIN (26). Thus, one should be careful in evaluating genomic instability based on the choice of the metric. Subsequently, we conducted a Spearman's correlation to analyze the relationship between each CIN metric across all tumor patient samples irrespective of the cancer type and within each cancer type. The results are depicted in Figure 1B, which further emphasizes that different "types" of CIN metrics capture varying aspects or patterns of genomic instability. Overall, Base Segments and FGA showed the most separation between tumor and non-tumor samples by cancer type, and as expected, the directionality of TAI for tumor compared to non-tumor samples is opposite of the other metrics (Figure 1A). Additionally, the tumor type impacts how well each CIN metric correlates with the others. For example, Base Segments and FGA show a positive correlation across all cancer types. However, when comparing Base Segments to TAI and FGA to TAI, the correlation varies based on cancer type. For both comparisons, there is a positive correlation in Lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). There is no correlation in Stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), Esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), Uterine carcinoma (UCS), and a negative correlation in Thymoma (THYM), Thyroid carcinoma (THCA), Acute myeloid leukemia (LAML).

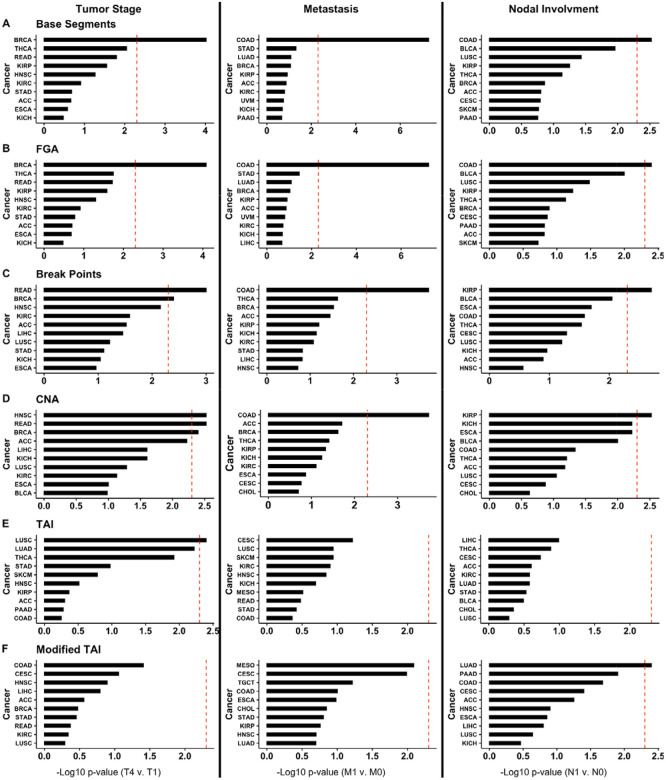

Next, we determined if each CIN metric is significantly associated with clinical characteristics by tumor type. For these analyses, we used the TNM (tumor stage, node, and metastasis) staging provided by TCGA for each of the 22 cancer types based on TNM data availability (Figure 2). We found that breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA; significant for Base Segments, FGA, Break Points, and CNA; Figure 2A-D), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ; significant for Break Points, and CNA; Figure 2C-D), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC; significant for CNA; Figure 2D), and LUSC (significant for TAI; Figure 1E) each had at least one CIN metric significantly associated with tumor stage (Mann Whitney Wilcoxon Test <0.05 after Bonferroni correction). However, only colon adenocarcinoma (COAD; significant for Base Segments, FGA, Break Points, and CNA; Figure 2A-D) had CIN metrics significantly associated with metastases. COAD (significant for Base Segments and FGA; Figure 2A-B), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP; significant for Break Points and CNA; Figure 2C-D), and lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD; significant for Modified TAI; Figure 2F) all had at least one CIN metric associated with nodal involvement (Mann Whitney Wilcoxon Test <0.05 after Bonferroni correction).

Figure 2.

Top ten cancers with the lowest Bonferroni-corrected p-values for (A) Base Segments, (B) FGA, (C) Break Points, (D) CNA, (E) TAI, and (F) Modified TAI association with tumor stage (T4 compared to T1), metastasis (M1 compared to M0), and nodal involvement (N1 compared to N0). TAI, total aberration index; CNA, copy number abnormality; FGA, fraction genome altered.

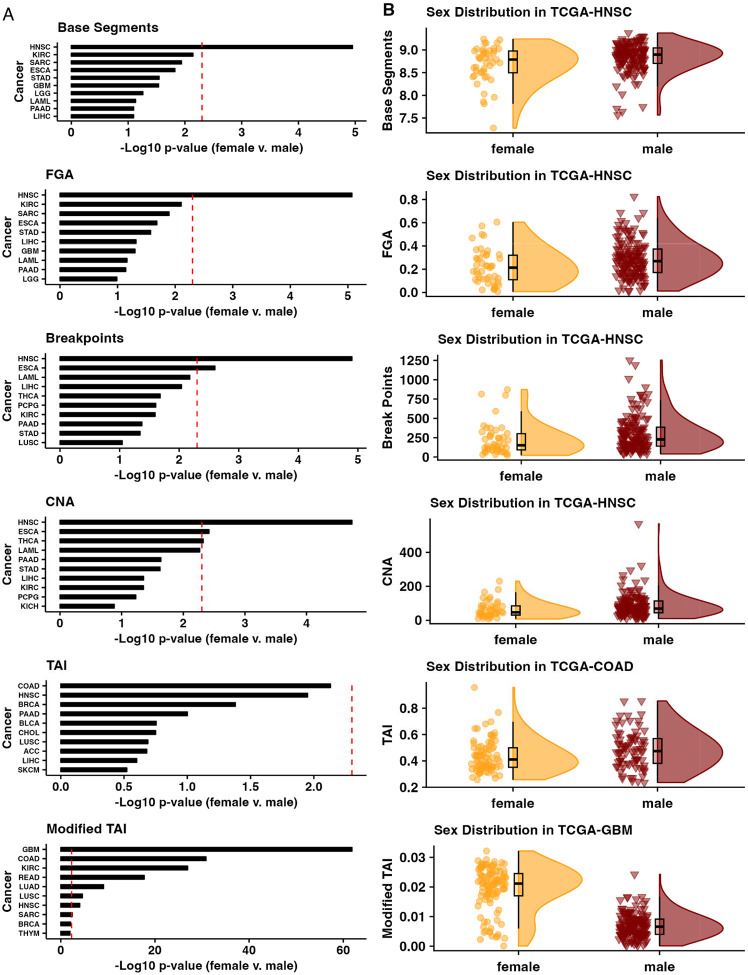

Finally, we compared CIN metrics by sex for each cancer by using the ‘gender’ (i.e., biological male or female) information provided by TCGA for each patient for the 27 cancer types with cases in both sexes (Figure 3). We found that HNSC CIN was significantly different between the sexes based on the Base Segments, FGA, Break Points, CNA, and Modified TAI metrics. However, esophageal carcinoma (ESCA) was significantly different between the sexes based on the Break Points and CNA metrics (Figure 3A-B), THCA based on the CNA metric (Figure 3A), and GBM (Figure 3A-B), COAD (Figure 3A-B), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), READ, LUAD, and LUSC based on the Modified TAI metric (Mann Whitney Wilcoxon Test <0.05 after Bonferroni correction, Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Top ten cancers with the lowest Bonferroni-corrected p-values between the sexes for each CIN metric and the (B) distribution of CIN metric scores for the most different tumor cohort by sex for each CIN metric. CIN, chromosomal instability.

4. Discussion

Here we evaluated how the TAI, Modified TAI, CNA, Base Segments, Break Points, and FGA copy number aberration CIN surrogates (ie., names..) compared across TCGA cohorts by assessing each across tumor types, how they associate with tumor stage, metastasis, and nodal involvement, and with respect to patient sex. We found that the tumor type impacts how well any two given CIN metrics correlate. While we also identified overlap between CIN metrics regarding their association with clinical characteristics (e.g., CIN was significantly associated with tumor stage in BRCA for 4 of the 6 metrics) and patient sex (e.g., CIN was significantly different between the sexes in HNSC for 5 of the 6 metrics), there was not complete agreement between metrics. We identified several cases where only one CIN metric was significantly associated with a clinical characteristic or patient sex for a given tumor type (e.g., Modified TAI was the only CIN metric significantly associated with nodal involvement for LUAD). Therefore, caution should be used when describing CIN based on any one metric or when comparing across studies (27).

A recent study of 1,421 samples from 394 tumors across 22 tumor types demonstrates that somatic copy number aberrations in cancer are both pervasive (i.e., occurring at least once in 99% of tumors) and dynamic (i.e., more than 20% of the genome was subject to subclonal somatic copy number aberrations in 45% of tumors) (28). Generally, CIN has been associated with distinct cancer etiologies and progression, patient prognosis, drug efficacy, and drug resistance in tissue- and tumor-specific manners (4-11,29,30). For example, van Dijk et al. (30) found that variation in the chromosomal copy number within a tumor (CIN heterogeneity) was strongly associated with poor survival in patients with solid tumors such as breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. However, as we show, the choice of metric used to calculate CIN can affect the measurement of such variation. In (29), Lukowet al. discuss the role of aneuploidy in cancer drug resistance by either overexpression of genes that suppress DNA repair, promote cell growth, or through the accumulation of mutations in genes that encode DNA repair enzymes. Thus, in such cases measuring not only the CIN but the region where it occurs might be more useful for predicting drug resistance. While this indicates that CIN may be a promising biomarker of patient prognosis and drug response, a thorough understanding of how to measure and interpret CIN is critical. Our study further underscores the need to be specific about how and when during the disease course CIN is calculated and that patient characteristics like sex may impact or be associated with such metrics. For example, a previous study has reported that 73.1% of HNSC patients were male (31), and Park et al. show that males are at a 2.9-fold increased risk of HNSC, independently of tobacco and alcohol consumption (32). Additionally, multiple studies have shown an association between increased CIN and HNSC risk (33,34), all of which is in agreement with our report of higher CIN (for 5 out of 6 metrics) in males with HNSC.

The metrics used in this study reflect distinct aspects of CIN, such as numerical aberrations, structural aberrations, or whole genome instability, and each aspect may have different biological implications. For example, numerical aberrations might lead to a higher degree of genetic diversity within a tumor, providing a larger pool of genetic variants for natural selection to act upon. This could accelerate tumor evolution and adaptation, potentially leading to more aggressive or treatment-resistant cancers. Whereas, structural aberrations might disrupt specific genes or regulatory elements, leading to more targeted effects on cell function (35-37).

There are several limitations to this study. The first is that these CIN metrics are calculated based on one genomic profile generated from a tumor, or a tumor sample, at a given time. Tumors are often very heterogeneous, including across time, so this provides only a snapshot of a dynamic system (27). Recent studies have underscored that some tumor types have a strong correlation between CIN and metastasis that may be associated with the timing of copy number aberrations occurring during tumor development as well as the tissue of origin (38). Additionally, the data used to calculate the scores in this study are array-based intensity scores from bulk profiles (18). High-throughput sequencing and single-cell technologies will continue to allow for more comprehensive profiling and provide an opportunity for future studies to characterize cancer CIN more precisely (39). While we examined how clinical (e.g., tumor stage) or patient (e.g., sex) associated with metrics of CIN, limited sample numbers preclude examining many factors simultaneously across all cancers. Finally, this brief report does not investigate how different causes of CIN may influence these metrics.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated 6 different CIN metrics (TAI, Modified TAI, CNA, Break Points, Base Segments, and FGA) present in the literature, across 33 cancers present in TCGA. We find that the tumor type significantly impacts the correlation between any two given CIN metrics. While there was an overlap between CIN metrics associated with clinical characteristics and patient sex, there was not complete agreement between metrics. CIN is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that cannot be fully captured by a single CIN metric; therefore, we caution against using a single metric as a proxy of CIN, particularly if developing CIN as a proxy for drug response or cancer progression for clinical settings.

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank the members of the Lasseigne Lab for their critical and constructive feedback.

Funding Statement

ST, VHO, JLF, and BNL were supported by R00HG009678. ST, VHO, TMS, JLF, and BNL were supported by UAB funds to the Lasseigne Lab.

Acronyms:

- CIN

Chromosomal Instability

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TAI

Total Aberration Index

- CNA

Copy Number Abnormality

- FGA

Fraction of Genome Altered

- CNV

Copy Number Variation

- TNM

Tumor stage, node, and metastasis

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- LAML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- OV

Ovarian cancer

- THYM

Thymoma

- UCS

Uterine carcinoma

- DLBC

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- PCPG

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- UCEC

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- SARC

Sarcoma

- PRAD

Prostate adenocarcinoma

- LGG

Brain lower grade glioma

- TGCT

Testicular germ cell tumors

- CESC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma, and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- LUSC

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- STAD

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- ESCA

Esophageal carcinoma

- THCA

Thyroid carcinoma

- BRCA

Breast invasive carcinoma

- READ

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- HNSC

Head and neck squamous carcinoma

- COAD

Colon adenocarcinoma

- KIRP

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- KIRC

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Ethics Approval Statement

This study was not classified as human subjects research or clinical investigation, and was determined to be exempt by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board.

CRediT Statement:

ST: Software, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization; VHO: Methodology, Software, Validation, Data Curation, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization, Project Administration; TMS: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Review & Editing, Visualization; JLF: Data Curation, Writing-Review & Editing; BNL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are openly available at the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) as ‘TCGA Level 3’ data. In addition, all analyses associated with this paper are on GitHub (https://github.com/lasseignelab/CINmetrics_Cancer_Analysis) and available at https://zenodo.org/record/7942543#.ZGPu8OzMJ4A.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011. Mar 4;144(5):646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022. Jan;12(1):31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGranahan N, Burrell RA, Endesfelder D, Novelli MR, Swanton C. Cancer chromosomal instability: therapeutic and diagnostic challenges. EMBO Rep. 2012. Jun 1;13(6):528–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tijhuis AE, Johnson SC, McClelland SE. The emerging links between chromosomal instability (CIN), metastasis, inflammation and tumour immunity. Mol Cytogenet. 2019. May 14;12:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lukow DA, Sausville EL, Suri P, Chunduri NK, Wieland A, Leu J, et al. Chromosomal instability accelerates the evolution of resistance to anti-cancer therapies. Dev Cell [Internet]. 2021. Aug 2; Available from: 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakhoum SF, Compton DA. Chromosomal instability and cancer: a complex relationship with therapeutic potential. J Clin Invest. 2012. Apr;122(4):1138–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson LR, Chen H, Collins AR, Connell M, Damia G, Dasgupta S, et al. Genomic instability in human cancer: Molecular insights and opportunities for therapeutic attack and prevention through diet and nutrition. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015. Dec;35 Suppl:S5–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Jaarsveld RH, Kops GJPL. Difference Makers: Chromosomal Instability versus Aneuploidy in Cancer. Trends Cancer Res. 2016. Oct;2(10):561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-David U, Amon A. Context is everything: aneuploidy in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2020. Jan;21(1):44–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson SL, Bakhoum SF, Compton DA. Mechanisms of chromosomal instability. Curr Biol. 2010. Mar 23;20(6):R285–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weaver BAA, Silk AD, Montagna C, Verdier-Pinard P, Cleveland DW. Aneuploidy acts both oncogenically and as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell. 2007. Jan;11(1):25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birkbak NJ, Eklund AC, Li Q, McClelland SE, Endesfelder D, Tan P, et al. Paradoxical relationship between chromosomal instability and survival outcome in cancer. Cancer Res. 2011. May 15;71(10):3447–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakhoum SF, Danilova OV, Kaur P, Levy NB, Compton DA. Chromosomal instability substantiates poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011. Dec 15;17(24):7704–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumbusch LO, Helland Å, Wang Y, Liestøl K, Schaner ME, Holm R, et al. High levels of genomic aberrations in serous ovarian cancers are associated with better survival. PLoS One. 2013. Jan 23;8(1):e54356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison JM, Yee M, Krill-Burger JM, Lyons-Weiler MA, Kelly LA, Sciulli CM, et al. The degree of segmental aneuploidy measured by total copy number abnormalities predicts survival and recurrence in superficial gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2014. Jan 16;9(1):e79079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee AJX, Endesfelder D, Rowan AJ, Walther A, Birkbak NJ, Futreal PA, et al. Chromosomal instability confers intrinsic multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 2011. Mar 1;71(5):1858–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chin SF, Teschendorff AE, Marioni JC, Wang Y, Barbosa-Morais NL, Thorne NP, et al. High-resolution aCGH and expression profiling identifies a novel genomic subtype of ER negative breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8(10):R215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oza VH, Fisher JL, Darji R, Lasseigne BN. CINmetrics: an R package for analyzing copy number aberrations as a measure of chromosomal instability. PeerJ. 2023. Apr 25;11:e15244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colaprico A, Silva TC, Olsen C, Garofano L, Cava C, Garolini D, et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016. May 5;44(8):e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spearman C. nThe Proof and Measurement of Association Between Two Things, oAmerican J. Psychol; 1904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Computing R, Others. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Core Team; [Internet]. 2013; Available from: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/6853895/r-a-language-and-environment-for-statistical-computing [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016. Sep 15;32(18):2847–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mann HB, Whitney DR. On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann Math Stat. 1947;18(1):50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilcoxon F. Some Uses of Statistics in Plant Pathology. Biometrics Bulletin. 1945;1(4):41–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassambara A. Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests [R package rstatix version 0.7.0]. 2021. Feb 13 [cited 2022 Feb 1]; Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalczyk K, Bartnik-Głaska M, Smyk M, Plaskota I, Bernaciak J, Kędzior M, et al. Comparative Genomic Hybridization to Microarrays in Fetuses with High-Risk Prenatal Indications: Polish Experience with 7400 Pregnancies. Genes . 2022. Apr 14;13(4):690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lepage CC, Morden CR, Palmer MCL, Nachtigal MW, McManus KJ. Detecting Chromosome Instability in Cancer: Approaches to Resolve Cell-to-Cell Heterogeneity. Cancers [Internet]. 2019. Feb 15;11(2). Available from: 10.3390/cancers11020226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watkins TBK, Lim EL, Petkovic M, Elizalde S, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, et al. Pervasive chromosomal instability and karyotype order in tumour evolution. Nature. 2020. Nov;587(7832):126–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukow DA, Sheltzer JM. Chromosomal instability and aneuploidy as causes of cancer drug resistance. Trends Cancer Res. 2022. Jan;8(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Dijk E, van den Bosch T, Lenos KJ, El Makrini K, Nijman LE, van Essen HFB, et al. Chromosomal copy number heterogeneity predicts survival rates across cancers. Nat Commun. 2021. May 27;12(1):3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakhry C, Krapcho M, Eisele DW, D’Souza G. Head and neck squamous cell cancers in the United States are rare and the risk now is higher among white individuals compared with black individuals. Cancer. 2018. May 15;124(10):2125–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park JO, Nam IC, Kim CS, Park SJ, Lee DH, Kim HB, et al. Sex Differences in the Prevalence of Head and Neck Cancers: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study of 10 Million Healthy People. Cancers [Internet]. 2022. May 20;14(10). Available from: 10.3390/cancers14102521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang LE, Xiong P, Zhao H, Spitz MR, Sturgis EM, Wei Q. Chromosome instability and risk of squamous cell carcinomas of head and neck. Cancer Res. 2008. Jun 1;68(11):4479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang J, Chen Y, Luo H, Cai H. The Landscape of Somatic Copy Number Alterations in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020. Mar 12;10:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baudoin NC, Bloomfield M. Karyotype Aberrations in Action: The Evolution of Cancer Genomes and the Tumor Microenvironment. Genes [Internet]. 2021. Apr 12;12(4). Available from: 10.3390/genes12040558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuzmin E, Baker TM, Lesluyes T, Monlong J, Abe KT, Coelho PP, et al. Evolution of chromosome arm aberrations in breast cancer through genetic network rewiring [Internet]. bioRxiv. 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 24]. p. 2023.06.10.544434. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.06.10.544434v6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pierzyna-Świtała M, Sędek Ł, Mazur B. Genetic and immunophenotypic diversity of acute leukemias in children. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej. 2022. Jan 1;76(1):369–79. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen B, Fong C, Luthra A, Smith SA, DiNatale RG, Nandakumar S, et al. Genomic characterization of metastatic patterns from prospective clinical sequencing of 25,000 patients. Cell. 2022. Feb 3;185(3):563–75.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Funnell T, O’Flanagan CH, Williams MJ, McPherson A, McKinney S, Kabeer F, et al. Single-cell genomic variation induced by mutational processes in cancer. Nature. 2022. Dec;612(7938):106–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support this study are openly available at the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) as ‘TCGA Level 3’ data. In addition, all analyses associated with this paper are on GitHub (https://github.com/lasseignelab/CINmetrics_Cancer_Analysis) and available at https://zenodo.org/record/7942543#.ZGPu8OzMJ4A.