Abstract

Sensory systems allow pathogens to differentiate between different niches and respond to stimuli within them. A major mechanism through which bacteria sense and respond to stimuli in their surroundings is two-component systems (TCSs). TCSs allow for the detection of multiple stimuli to lead to a highly controlled and rapid change in gene expression. Here, we provide a comprehensive list of TCSs important for the pathogenesis of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC). UPEC accounts for >75% of urinary tract infections (UTIs) worldwide. UTIs are most prevalent among people assigned female at birth, with the vagina becoming colonized by UPEC in addition to the gut and the bladder. In the bladder, adherence to the urothelium triggers E. coli invasion of bladder cells and an intracellular pathogenic cascade. Intracellular E. coli are safely hidden from host neutrophils, competition from the microbiota, and antibiotics that kill extracellular E. coli. To survive in these intimately connected, yet physiologically diverse niches E. coli must rapidly coordinate metabolic and virulence systems in response to the distinct stimuli encountered in each environment. We hypothesized that specific TCSs allow UPEC to sense these diverse environments encountered during infection with built-in redundant safeguards. Here, we created a library of isogenic TCS deletion mutants that we leveraged to map distinct TCS contributions to infection. We identify – for the first time – a comprehensive panel of UPEC TCSs that are critical for infection of the genitourinary tract and report that the TCSs mediating colonization of the bladder, kidneys, or vagina are distinct.

INTRODUCTION

Whether to newly colonized niches or to changing conditions, bacteria efficiently adapt to environmental changes by rapidly changing gene expression (1, 2). A major mechanism through which bacteria interpret environmental changes into specific changes in their gene expression is two-component signal transduction systems (TCSs). TCSs are usually comprised of two parts: a sensor histidine kinase (HK) and a cognate response regulator (RR). Typically, signal interception results in HK autophosphorylation at a conserved histidine residue and subsequent phosphotransfer to a conserved aspartate on the RR. The most widely observed outcome of RR phosphorylation is increased DNA binding affinity of the phosphorylated RR for its target promoters, consequently altering target gene expression.

Compartmentalized, TCSs serve as bacterial logic gates that process sensory input with the net output result often being a change in gene expression that ultimately changes one or multiple bacterial phenotypes. However, multiple studies show that – like in mammalian signaling systems – TCSs are dynamic and branch to incorporate multiple stimuli, interact outside the boundaries of cognate partners, or be part of phosphorelays that allow for a refined, beneficial orchestration of molecular systems (3). While these phenomena are well-characterized in vitro, either in biochemical protein-protein interactions or in the test tube, few studies have investigated how each TCS of a given pathogen contributes to host colonization.

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is the causative agent of ~80% of the 150 million urinary tract infections (UTIs) that occur annually (4–6). UPEC’s ability to survive within several different environments contributes to its successful prevalence. UPEC can be transmitted amongst individuals through the fecal-oral route and sexual contact (4). Within the intestinal tract, UPEC colonizes the human gut alongside commensals for extended periods of time, in contrast to diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes (6–8). However, unlike commensals, the genetically diverse UPEC strains are equipped with fitness determinants that allow them to expand beyond the gut (8–11). Exit from the gut, is followed by urethral accession to the bladder causing cystitis. During bladder infection, UPEC dynamically reach the kidney and in some cases can cause pyelonephritis, from where bacteria can traverse to the bloodstream, leading to bacteremia (12–14). In people assigned female at birth, who are disproportionally impacted by UTIs, UTI pathogenesis additionally encompasses the vagina (15, 16). Within these different host niches, UPEC is found in extra- and intracellular compartments exposed accordingly to different stresses and metabolite inventories. In the bladder and vaginal lumens, UPEC exist planktonically or associated with the urothelial or vaginal cells. Likewise in the kidney, UPEC associates with the host cell membrane (17). In the host intracellular environments, UPEC form three different intracellular bacterial reservoirs: metabolically active, biofilm-like, intracellular bacterial communities (IBCs) in the superficial umbrella cells of the bladder; quiescent intracellular reservoirs inside transitional bladder cells and vaginal intracellular communities within vaginal epithelial cells (15, 18).

While the field has developed an in-depth understanding of the molecular systems contributing to UPEC’s plasticity, such as flagella curli, and type 1 and P pili, little is known about which TCSs are coordinately used during infection. In this work, we tested the hypothesis that the different unique niches UPEC encounters necessitate the use of distinct TCSs. To test this hypothesis, we constructed an isogenic deletion mutant library of all the TCSs encoded by the prototypical cystitis isolate UTI89 (Table 1) that is extensively used in the field to study UTI pathogenesis (19). As this is the first time a comprehensive TCS deletion library has been constructed for study in a UPEC isolate, an in-depth in vitro analysis of how each TCS deletion strain associates with bladder cells is was first performed. Next, we leveraged our well-established UTI mouse models to determine the pathogenicity of each TCS deletion mutant in the bladder, kidneys, and vagina. We report that in vitro, none of the TCSs deletion mutants substantially influences adherence or invasion of urothelial cells, indicating that this critical step in infection establishment is under redundant control. Our in vivo data uncover – for the first time – the inventory of TCSs needed for bacterial expansion following the adherence and invasion steps in the bladder. These TCSs are distinct from the TCSs that we found to be critical for kidney or vaginal colonization following bladder infection. Collectively, our results demonstrate niche-specific requirements for TCSs during the different stages of UTIs and lay the groundwork for delineating mechanistic details associated with each network during UPEC infection.

Table 1: Information on HK – RR pairs and orphan proteins in UPEC strain UTI89.

All information was compiled using P2CS and MiST3.0 databases.

| HK | Loci | RR | Loci | Ligand or stimulating conditions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ArcB | C3646 | ArcA | C5174 | Anaerobic growth | (51) |

| AtoS | C2501 | AtoC | C2502 | Acetoacetate | (52) |

| BaeS | C2353 | BaeR | C2354 | Envelope stress, indole, and flavonoids | (53) |

| BarA | C3156 | UvrY | C2115 | Acetate and short-chain fatty acids | (54) |

| BtsS | C2398 | BtsR | C2397 | Pyruvate | (55) |

| ╱ | C4639 | ╱ | C4638 | Unknown | ╱ |

| ╱ | C4932 | ╱ | C4931 | Unknown | ╱ |

| ╱ | C4937 | ╱ | ╱ | Unknown | ╱ |

| CpxA | C4495 | CpxR | C4496 | Envelope stress | (56) |

| CreC | C5170 | CreB | C5171 | During glucose fermentation | (57) |

| CusS | C0570 | CusR | C0571 | Copper and silver | (58) |

| DcuS | C4719 | DcuR | C4718 | Prescence of C4-dicarboxylates like malate | (59, 60) |

| DpiB | C0624 | DpiA | C0624 | Citrate | (61) |

| EnvZ | C3904 | OmpR | C3905 | Changes is osmolarity | (62) |

| EvgS | C2702 | EvgA | C2701 | Alkali metals and low pH | (63) |

| GlnL | C4458 | GlnG | C4457 | Nitrogen deprivation | (64) |

| KdpD | C0699 | KdpE | C0698 | Potassium limitation | (65) |

| NarQ | C2795 | ╱ | ╱ | Nitrate and nitrite | (66) |

| NarX | C1418 | NarL | C1417 | Nitrate and nitrite | (66, 67) |

| PhoQ | C1258 | PhoP | C1259 | Low magnesium and calcium and membrane stress | (68, 69). |

| PhoR | C0421 | PhoB | C0420 | Inorganic phosphate | (70) |

| PmrB | C4706 | PmrA | C4707 | Ferric iron and membrane stress | (71) |

| QseC | C3451 | QseB | C3450 | Unknown | ╱ |

| QseE | C2876 | QseF | C2873 | Adrenergic receptor | (72) |

| RcsCD | C2500,C2498 | RcsB | C2499 | Osmotic shock | (73) |

| RstB | C1796 | RstA | C1797 | Unknown | ╱ |

| TorS | C1056 | TorR | C1059 | Trimethylamine-N-oxide | (74) |

| UhpB | C4224 | UhpA | C4225 | Glucose-6-phosphate | (75) |

| YedV | C2167 | YedW | C2168 | Hydrogen peroxide responsive | (76) |

| YpdA | C2712 | YpdB | C2713 | High pyruvate concentrations | (55) |

| ZraS | C3816 | ZraR | C3815 | Zinc | (77) |

| ╱ | ╱ | NarP | C2471 | Nitrate and nitrite | (66) |

| ╱ | ╱ | RssB | C1431 | Glucose, phosphate, and nitrogen deprivation | (78) |

METHODS

Ethics Statement:

Ethics approval for mouse experiments was granted by the VUMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (protocol numbers M1800101–01). Experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health and IACUC at VUMC.

Growth of Eukaryotic Cells and Bacterial strains:

A complete list of E. coli strains and their characteristics used for this study are listed in Table S1. From freezer stocks, strains were grown in 5 mL of lysogeny broth (LB) at 37 °C with shaking. For bacteriological assays, LB culture tubes were incubated overnight. For inoculation of 5637 (ATCC HTB-9) cells and C3H/HeN mice, bacterial cultures were first seeded from a freezer stock and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C, followed by two sequential, ~24h sub-cultures (1:1000 dilution) in 10 mL, static LB media at 37 °C in-order to induce type 1 pili (19). Preceding inoculation of immortalized cells and mice, strains were normalized in 1x PBS. The immortalized bladder epithelial cell line 5637 (ATCC HTB-9) was grown statically at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies Co., Grand Island, NY) media supplemented with 10% FBS under 5% CO2.

Construction of UPEC TCS Deletion Library:

A complete list of plasmids and primers can be found in Tables S2 and S3, respectively. For our study, we used the genetically tractable, cystitis strain UTI89 and using the prokaryotic TCS databases, P2CS and MiST, identified a comprehensive list of TCSs in UTI89 for deletion (20, 21). Targeted TCS deletion mutants for the isogenic deletion library were constructed using the λ Red recombinase system and gene deletion was confirmed by PCR with test primers (22, 23).

Bacterial Growth Curves:

Strains were grown overnight in LB broth and sub-cultured to a starting OD600 of 0.05 in the specified broth in a 96-well plate. Plates were incubated at 37°C with shaking for 8 h and OD600 readings taken every 15 min. Growth data was fit to the Weibull growth model to determine specific growth rate (24).

Gentamicin-Based Protection Assays:

Experiments were performed as described elsewhere (25). 5637 (ATCC HTB-9) bladder epithelial cells were grown to at least 90% confluency in 24-well plates. Prior to inoculation with E. coli, new RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% was added to the cells. To achieve an approximate MOI of 5, 5637 cell density was enumerated to determine the amount of E. coli suspension to be used per well. Strain inoculum was added to three sets of triplicate wells and centrifuged for 5 min at 600×g to facilitate uniform contact between bladder and bacteria cells. Following, plates were incubated at 5% CO2 and 37 °C for 2 h. For cell lysis, a final concentration of 0.1% Triton X-100 was used. Bacterial burden was enumerated by serial dilution and spot platting onto LB plates. One set of wells was lysed to determine the total number of bacteria within the well. The other two sets were washed with 0.5 mL of PBS three times. The E. coli adhering to bladder cells was enumerated in a set of wells that was immediately lysed after the washes. The final set of wells were gently washed with PBS with 100 μg/mL of gentamicin (Life Technologies Co., Grand Island, NY) for 2h; afterwards, wells were washed two more times with 1 mL of PBS to enumerate the intracellular E. coli. The percent of E. coli adherence and invasion were calculated as a percentage of the total number of bacteria.

Mouse UTI Model:

Mouse infectious were performed as previously described (26, 27). E. coli strains were incubated at 37 °C, initially in a 5 mL LB culture tube with shaking for 4 h and followed by two sequential sub-cultures at 1:1,000 into 10 mL of fresh LB and grown statically for 24 h. C3H/HeN female mice at 7- to 8-weeks-old were transuretherally inoculated with 50 μL an E. coli suspension of 107 CFUs in PBS and mice were humanly euthanized at 6 h, 24 h, or 28 days post-infection (h/dpi). After euthanasia, organs were removed and homogenized in PBS for CFU enumeration. For quantification of intracellular bacteria, bladder tissue was incubated in 100 μg/mL of gentamicin for 2 h, washed with PBS, and homogenized in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100.

Visualization and Enumeration of intracellular bacterial communities:

IBC enumeration was performed as described previously using bacterial strains transformed with pCOM::GFP plasmid (13). Mice were euthanized 6 hpi and the bladders were removed with aseptic technique. Mouse bladders were stretched, pinned, and fixed with 3.4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C. Bladders were washed twice in 1X PBS, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, followed by a 1XPBS wash. Bladders were stained at room temperature with Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin (ThermoFisher) and mounted on to slides with ProLong Diamond Antifade (ThermoFisher). IBCs were manually counted via fluorescence microscopy on a LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss).

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism software, using the most appropriate test for each analysis. Experiments were performed in accordance with the standard convention, incorporating at least three biological replicates. Statistical tests used for analysis are two-tailed. Additionally, for mouse infections, power analyses were performed to determine seven subjects per group are needed to achieve a power level of 90% for detecting a 25% difference in the CFU means with an in-group standard deviation of 20%. Additional experimental details of group size, statistical test, error bars, and probability value for each statistically evaluated experiment are specified in the corresponding figures, legends, and text.

RESULTS

Construction of a UPEC TCS deletion library:

Using the P2CS and MiST3.0 databases, we compiled a list of TCS within the UPEC strain UTI89. In UTI89, we found 32 RRs and HKs, including four hybrid HKs (Table 1). Typically, classical TCSs components are encoded together in an operon; however, in some cases TCS component genes are encoded at distinct loci in the chromosome or comprise more complex multi-branch systems or phosphorelay systems, such as RcsCDB. Finally, certain strains, including UTI89, may encode “orphan” TCS components with no known interaction partners. Within UTI89, we identified 25 orthodox pairs and 14 orphans, including one without a known partner. In order to construct a comprehensive TCSs deletion library in UTI89 accounting for gene separation, we generated 38 different isogenic deletion mutants. Orthodox TCSs were deleted in pairs, and orphans were deleted separately. For analysis, the rcsDB gene cluster that codes for the phosphorelay system RcsDBC, were deleted as a unit together. The unorthodox CheA-CheY chemosensory system, which has been heavily investigated in the context of chemotaxis (28, 29), was omitted from this study. All resulting mutant strains are marker-less and validated by PCR. To our knowledge, this is the first time a TCS deletion library is constructed in a UPEC isolate.

Deletion of a singular TCS pairs does not impair adherence or invasion of urothelial cells:

Prior to evaluating the contribution of each TCS to UPEC pathogenesis, we sought to determine whether deletion of any TCS negatively affects growth, adherence or invasion. To assess strains for their contribution to growth in vitro, we performed growth curves in nutrient limited N-minimal growth media or in the nutrient-rich lysogeny broth (LB). Growth curves were fit to the Weibull growth model to compare specific growth rates. The specific growth rate of UTI89 was 0.1962 ±0.0542 h−1 for N-minimal (Fig. 1A) and 0.1926 ±0.0222 h−1 for LB media (Fig. 1B) (mean ±95% CI) with no statistically significant difference compared to any of the TCS mutant strains tested). These results indicate that – under the conditions tested – not a single TCS is critical to planktonic growth of UPEC strain UTI89. We thus proceeded to evaluate the TCS deletion library on specific phenotypes associated with the initial stages of infection.

Figure 1: In vitro properties of UPEC TCS deletion mutants.

A) Graph depicts the specific growth rate of each TCS mutant compared to the isogenic parent UTI89, during growth in (A) N-minimal or (B) LB media with shaking, at 37°C. Growth curves were fit to the Weibull growth model to determine specific growth rate. (C) Adherent and (D) intracellular bacterial titers for wild-type UTI89 and each of the isogenic TCS deletion strains. Experiments were performed using an MOI of 5 on the immortalized urothelial cell line 5637. The percent of E. coli adherence and invasion were calculated as a percentage of the total number of bacteria with a well at the 2 h endpoint. Each dot represents a biological replicate. A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis with two-sided Dunn’s post-hoc test was performed for statistical analysis.

UPEC infection begins with adherence and invasion of urothelial cells. This process is governed by type 1 pili (fim), which are adhesive fibers assembled by the chaperone-usher pathway. A defect in adherence excludes invasion of the urothelium and constitutes a bottlenecking event. To determine if any of the UPEC TCS mutants display an adherence or invasion defect, we leveraged a well-established tissue culture model (25) using the 5637 immortalized urothelial cell line. These assays revealed that ΔyedVW and ΔkguRS mutants had adherence levels higher than the parental UTI89 strain (Fig. 1C). Nonetheless, enumeration of internalized bacteria did not identify statistically significant differences among strains (Fig. 1D). These data again indicate that no single TCS deletion impairs the initial steps in UPEC pathogenesis that typically acts as a bottleneck for studying downstream infection stages. Knowing that none of the TCS deletion strains has an adherence or invasion defect, we went on to test the entire deletion library in a murine UTI model.

Distinct TCSs contribute to colonization of genitourinary tract niches:

We next sought to evaluate the contribution of each TCS mutant in a UTI mouse model. In this model, UPEC adheres and invades urothelial cells, ascends to the kidney, and migrates to the vagina and gut in a dynamic fashion (26, 30, 31). Acute infection hallmarks include the formation of IBCs at 6 hpi and bacteriuria that persists over time in ~50% of the infected mice (27). Another hallmark of UTI that is captured in this murine model, is the formation of asymptomatic reservoirs in the vagina (30).

In this experiment, we asked how each TCS mutant colonizes three niches: the bladder, kidneys, and vagina (30). Cohorts of 6–8 week old female C3H/HeN mice were transuretherally inoculated with the wild-type parent or each of the isogenic TCS mutants. Mice were euthanized 24 hpi and bacterial titers in the bladder, kidneys, and vagina were enumerated for each infected mouse. These experiments revealed 12 different TCS deletion strains with altered bacterial titers (Fig. 2). Consistent with the hypothesis that distinct TCS are needed in unique sub-niches in the genitourinary tract, we observed mutants with niche-specific defects.

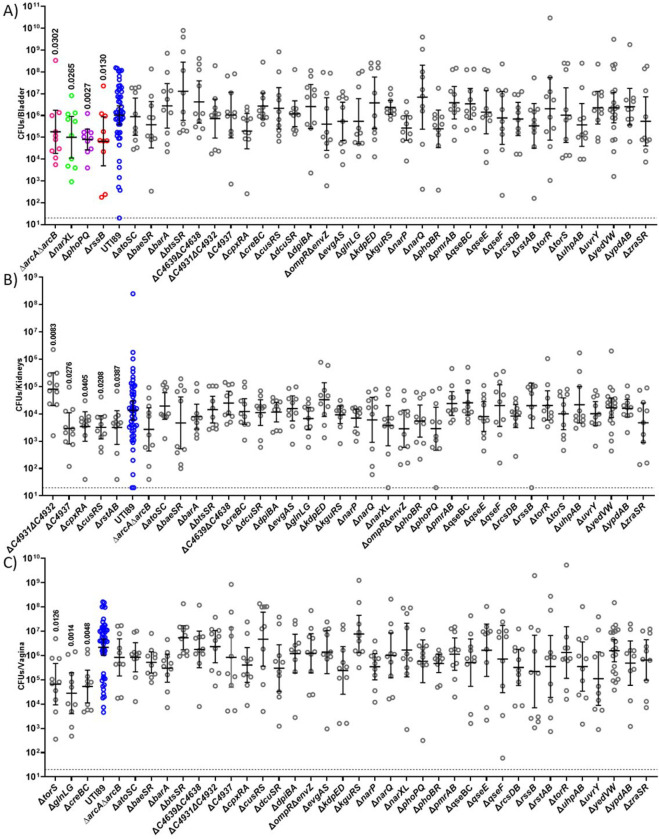

Figure 2: Niche-specific contribution of TCSs during 24h infection:

Mice infected with UTI89 (Blue) and isogeneic TCS deletion strains were euthanized 24 hpi for bacterial enumeration of titer within the (A) bladder, (B) kidneys, and (C) vagina. Each dot represents organ titers from a different mouse. A non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis with two-sided uncorrected Dunn’s post-hoc test was performed for statistical analysis.

In the bladder, the ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, ΔphoPQ and ΔrssB showed decreased titers compared to the parent strain at 24 hpi (Fig. 2A), but were able to colonize the kidney and transit to the vagina similar to the wild-type strain (Fig. 2B–C). Conversely, ΔC4931ΔC4932, ΔC4937, ΔcpxRA, ΔcusRS, ΔrstAB exhibited altered titers in the kidney (Fig. 2B), while ΔtorS, ΔcreBC, ΔglnLG exhibited significant colonization defects in the vagina (Fig. 2C) at 24 hpi. These different TCS make apparent contributions to the respective niches within the acute mouse model. Moreso, these results indicate that while these TCSs contribute to survival within a niche, they are dispensable for survival of the other two niches.

Mutants defective for bladder colonization are associated with energy metabolism:

Our lab has previously elucidated that aerobic respiration is critical for intracellular replication of UPEC (32). The current analyses uncover 4 TCS mutants, ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, ΔphoPQ, and ΔrssB RR that display defects in bladder colonization at 24 hpi. ArcA/ArcB, NarX/NarL and RssB belong to regulatory networks associated with respiration (33, 34), while PhoP/PhoQ is implicated in stress response and energy metabolism (35, 36) (Fig. 2A). We therefore focused on these regulators to further dissect the stage at which they become important during infection and to evaluate how their deletion impacts long-term persistence of UPEC in the urinary tract.

During UTI, UPEC become internalized by urothelial cells, in which they replicate into biofilm-like communities by consuming oxygen primarily via the quinol oxidase cytochrome bd (37). Previous work demonstrated that the activity of the ArcB HK is influenced by the quinol oxidation state and that both RssB and ArcA influence the abundance of the sigma factor σ38 (RpoS) that in turn influences the expression of biofilm components in E. coli (33, 38–41). To determine whether each bladder-defective TCS deletion mutant has the ability to form IBCs during acute infection, we evaluated intracellular bacterial titers and IBC formation at 6 hpi. To enumerate the extracellular and intracellular bladder populations, mice were euthanized at 6 hpi, and bladders were removed, bisected, and gentamicin-treated to eliminate extracellular bacteria and enable enumeration of the intracellular bacterial levels. These analyses revealed that all four mutants, ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, ΔphoPQ, and ΔrssB, are retained in the bladder lumen, with titers similar to the wild-type parent (Fig. 3A); in contrast to the extracellular fractions, the intracellular titers of the mutants were statistically significantly different than the parental strain titers. The mutants ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, and ΔphoPQ had high intracellular titers, whereas the ΔrssB mutant has drastically lower titers than the parental UTI89 strain (Fig. 3B) that are reminiscent of a mutant that lacks cytochrome bd (37). Based upon the 6 hpi bacterial titer analysis, we sought to determine whether the rssB or arcAB deletion resulted in altered IBC morphology or numbers. We performed microscopy on these selected strains at 6 hpi. We did not observe any apparent difference in IBC morphology or size (Fig. S1). We noted an abundance of IBCs in the ΔarcAΔarcB strain (Fig. 3C), which is consistent with the observed increase in intracellular bacterial titers. Conversely, there was a statistically significant lower number of IBCs in the ΔrssB infected bladders compared to the UTI89 strain (Fig. 3C), in agreement with the significantly lower numbers of intracellular numbers observed for the ΔrssB mutant. This experiment demonstrates that during the intracellular stage of infection ArcA/ArcB and RssB likely contribute to different aspects of the intracellular pathogenic cascade.

Figure 3: TCSs contribute to distinct stages of extracellular and intracellular pathogenesis.

A-B) Graphs depict the (A) luminal and (B) intracellular bacterial titers from mouse bladders assessed at 6 hpi. (C) Graph depicts the number of IBCs enumerated in each infected bladder at 6 hpi. Enumeration of IBCs was performed using confocal microscopy on randomly selected bladders. Statistical analysis was performed with Mann Whitney U test. D-G) Strains with aberrant acute infection titers were assessed in a long-term 28-day UTI model. D) Graph depicts time-to-resolution curves as defined as urine bacterial titers dropping below 104 CFUs/mL. Time to event was modeled with Kaplan-Meier method with non-parametric Mantel-Cox test for statistical comparison of TCS deletion mutants to UTI89. Post 28-day urine analysis, bacterial titers were enumerated in the mouse (E) bladder, (F) kidneys, and (F) vagina. Each symbol is a mouse. Statistical analysis was performed with Mann Whitney U test.

Following acute infection, C3H/HeN mice may develop chronic cystitis or the infections may resolve as indicated by bacterial urine titers dropping below 104 CFUs/mL. Chronic or resolved infection depends upon the bacteria clearing an early host-pathogen checkpoint within the first, 24 hours of acute infection (42, 43). We followed the urine titers of mice infected with either UTI89, ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, or ΔphoPQ for 28 dpi and measured bacterial organ titers on day 28. Longitudinal urinalysis showed that despite harboring higher numbers of intracellular bacteria at the 6 h time-point, mice infected with ΔarcAΔarcB, had a shorter time to resolution event, compared to wild-type UTI89 (Fig. 3D). Similarly, urine analysis showed that the ΔphoPQ, and ΔrssB infected mouse cohorts had a shortened time to resolution compared to those infected with UTI89 (Fig. 3D). At the 28-dpi endpoint, the ΔarcAΔarcB mutant was the only strain that was statistically significant in lower kidneys, bladder, and vagina titers than the parental UTI89 strain (Fig. 3E–G). The ΔphoPQ strain was significantly lower in the kidneys (Fig. 3F).

On a broad scale, these data indicate that TCSs make niche and time specific contributions to dynamic UPEC pathogenesis. On a finer scale, these data begin to indicate that UPEC may need to alternate between aerobic and anaerobic respiration states during different stages of infection. Collectively, our study elucidates the niche-specific TCS requirements of UPEC infection (Fig. 4); knowledge that we believe will seed future research on better understanding how UPEC regulate virulence and fitness determinants in a dynamic manner.

Figure 4: Summary of the different TCS and their relevant niches.

Overall, our data support redundant regulatory networks within TCSs. Among the many TCSs that UPEC encodes, 12 TCSs make critical, niche-specific contributions to UPEC pathogenesis.

DISCUSSION:

A key component to the success of UPEC as a pathogen of the urinary tract and a commensal of the gut and vagina, is its ability to thrive within a variety of different niches and in different states. While studies have thus far extensively focused on virulence factors and the UPEC pathogenic cascade itself, very few reports have investigated regulatory pathways associated with UPEC pathogenic potential. TCSs are a major regulatory mechanism that allow bacteria to switch between molecular tools in response to varying stimuli in their current environment. No studies have been executed to define how UPEC uses TCSs during infection. Here, we generated a deletion library of all the TCSs in the prototypical UPEC strain UTI89 as a tool to probe mechanisms of pathogenesis and persistence. We hope the future use of this library in the field enhances research in this area.

Our study highlights two critical aspects of UPEC TCSs: 1) they’re utilized under specific conditions and 2) likely form complex networks. While, there were no major differences between deletion strains during in vitro growth; clear molecular tissue tropisms were observed with in vivo experiments for a subset of TCSs. While different TCSs have been expansively studied at the molecular level in E. coli and context of gut colonization, only a few have been studied in the context of UPEC pathogenesis. Previous studies have connected a few TCSs to UPEC pathogenesis with a targeted individual approach. For instance, deletion of the ompR RR in NU149, which impacts fim expression, resulted in approximately 2-log reduction in bladder and kidney titers in BACLB/c mice (44). Deletion of the CpxAR system diminished UTI89 fitness in the bladder after 3 dpi in CBA/J mice (45). The BarA-UvrY system in UPEC CFT073 was reduced in bladder and kidney titers 3 dpi which was attributed to LPS and hemolysin production (46). Deletion of qseC alone was documented to lead to UTI89’s attenuation in the mouse bladder (47). These prior studies investigated single component deletions of either the RR or the HK, which can unmask non-partner interactions across TCSs. For this study, we generated a comprehensive TCS deletion library of each TCS pair with the exception or orphan components like RssB, or systems in which the deletion of both TCS partners proved difficult to obtain (barA/uvrY and torR/torS). This constructed inventory of TCS deletion mutants now allows for an expansive assessment of the TCSs and their downstream regulons within a variety of settings. In an acute UTI model, we found 12 different systems contributing to infection in either the bladder, kidney, or vaginal niches, focusing at 24 hpi (Fig. 2). The library can be leveraged to evaluate the fitness of the TCS mutants at different stages of infection. Moreover, future studies can determine how the fitness potential of each TCS mutant changes if they are inoculated directly in the asymptomatic niches (vagina or gut) instead of transurethrally instilled in the bladder. Will different TCSs become important for exiting the asymptomatic reservoirs and ascending the urethra to the bladder? We think so.

We acknowledge that in this study, we provide a broad view of a single cystitis isolate: the prototypical strain UTI89. UPEC genomic heterogeneity is extensive, and we posit that changes in genomic content may influence TCS use in a strain-specific fashion. Yet, we support that this study is significant as it provides the first comprehensive overview of TCSs to UPEC pathogenesis and lays the foundation for future in-depth investigations in other UPEC isolates and a comparison tool that is more representative than the model laboratory K-12 strains.

In the current study, and based on the expertise of our group, we selected to focus more closely with those TCS mutants that displayed a significant colonization defect in the bladder: ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔnarXL, ΔphoPQ and ΔrssB. (Fig. 2A, 4). Three of these mutants, ΔarcAΔarcB, ΔrssB, and ΔnarXL are convergent on the regulation of respiration, a critical aspect of UPEC pathogenesis. Under microaerobic conditions ArcA is connected to the up-regulation of cydAB and down-regulation of cyoABCDE (48, 49). Recently, cydAB, which encodes the cytochrome bd oxidase, was found critical for proper IBC expansion (32). The expression of cydAB and arcA are also regulated by the global one component regulator FNR, which is active at low oxygen levels (49, 50). Along with FNR, the HK NarX, which helps to discern between nitrate and nitrite, phosphorylates NarL which in turn regulates narG expression, which is a nitrate reductase. The cytochrome bd oxidase and nitrate reductase renew the ubiuinone:ubiquinol pool though be it under different conditions (34). The HK, ArcB controls the phosphorylated state of the RRs ArcA and RssB that co-regulate the balance in RpoS abundance in response to general stress like carbon starvation (33). While our results indicate that the TCS important to cystitis seem to converge on respiration the details to their direct or indirect interactions down or upstream of one another remain to be explored. Further study may reveal details of interconnectivity of these TCSs involved in an energetics balancing act.

In sum, two-component systems are critical systems that mediate a pathogen’s ability to adapt behavior in response to external stressors. TCSs have global impacts on metabolism and virulence factors or targeted towards a narrow regulon. This work provides a comprehensive tool to dissect UPEC pathogenesis from a regulation standpoint and highlight that TCSs are important for UPEC pathogenesis in a niche specific manner.

IMPORTANCE.

While two-component system (TCS) signaling has been investigated at depth in model strains of E. coli, there have been no studies to elucidate – at a systems level – which TCSs are important during infection by pathogenic Escherichia coli. Here, we report the generation of a markerless TCS deletion library in a uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) isolate that can be leveraged for dissecting the role of TCS signaling in different aspects of pathogenesis. We use this library to demonstrate, for the first time in UPEC, that niche-specific colonization is guided by distinct TCS groups.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants T32GM007569 (JRB), R01AI107052 (MH), P20DK123967 (MH), R01AI168468 (MH), F30AI169748 (SAR) and F30AI150077 (CJB), T32GM007347 (CJB). Confocal laser scanning microscopy in Fig. S1 was performed at the Vanderbilt Cell Imaging Shared Resource (CISR), which is supported by NIH grant DK20593. Some images were created using BioRender.com.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflicts of interest at the time of submission of this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Prüß BM. 2017. Involvement of Two-Component Signaling on Bacterial Motility and Biofilm Development. J Bacteriol 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cases I, de Lorenzo V, Ouzounis CA. 2003. Transcription regulation and environmental adaptation in bacteria. Trends Microbiol 11:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laub MT, Goulian M. 2007. Specificity in two-component signal transduction pathways. Annu Rev Genet 41:121–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foxman B. 2014. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin North Am 28:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Echols RM, Tosiello RL, Haverstock DC, Tice AD. 1999. Demographic, clinical, and treatment parameters influencing the outcome of acute cystitis. Clin Infect Dis 29:113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Czaja CA, Scholes D, Hooton TM, Stamm WE. 2007. Population-based epidemiologic analysis of acute pyelonephritis. Clin Infect Dis 45:273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL, Wu M, Henderson JP, Hooton TM, Hibbing ME, Hultgren SJ, Gordon JI. 2013. Genomic diversity and fitness of E. coli strains recovered from the intestinal and urinary tracts of women with recurrent urinary tract infection. Sci Transl Med 5:184ra60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schreiber HL, Spaulding CN, Dodson KW, Livny J, Hultgren SJ. 2017. One size doesn’t fit all: unraveling the diversity of factors and interactions that drive. Ann Transl Med 5:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobrindt U, Agerer F, Michaelis K, Janka A, Buchrieser C, Samuelson M, Svanborg C, Gottschalk G, Karch H, Hacker J. 2003. Analysis of genome plasticity in pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli isolates by use of DNA arrays. J Bacteriol 185:1831–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch RA, Burland V, Plunkett G, Redford P, Roesch P, Rasko D, Buckles EL, Liou SR, Boutin A, Hackett J, Stroud D, Mayhew GF, Rose DJ, Zhou S, Schwartz DC, Perna NT, Mobley HL, Donnenberg MS, Blattner FR. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:17020–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lloyd AL, Rasko DA, Mobley HL. 2007. Defining genomic islands and uropathogen-specific genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 189:3532–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lane MC, Alteri CJ, Smith SN, Mobley HL. 2007. Expression of flagella is coincident with uropathogenic Escherichia coli ascension to the upper urinary tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:16669–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz DJ, Chen SL, Hultgren SJ, Seed PC. 2011. Population dynamics and niche distribution of uropathogenic Escherichia coli during acute and chronic urinary tract infection. Infect Immun 79:4250–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamm WE, McKevitt M, Roberts PL, White NJ. 1991. Natural history of recurrent urinary tract infections in women. Rev Infect Dis 13:77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brannon JR, Dunigan TL, Beebout CJ, Ross T, Wiebe MA, Reynolds WS, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2020. Invasion of vaginal epithelial cells by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Commun 11:2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherf H, Köllermann MW. 1977. [The periurethral flora in female patients with recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) (author’s transl)]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 125:787–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lane MC, Mobley HL. 2007. Role of P-fimbrial-mediated adherence in pyelonephritis and persistence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) in the mammalian kidney. Kidney Int 72:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mysorekar IU, Hultgren SJ. 2006. Mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli persistence and eradication from the urinary tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:14170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Hultgren SJ. 2001. Establishment of a persistent Escherichia coli reservoir during the acute phase of a bladder infection. Infect Immun 69:4572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortet P, Whitworth DE, Santaella C, Achouak W, Barakat M. 2015. P2CS: updates of the prokaryotic two-component systems database. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D536–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gumerov VM, Ortega DR, Adebali O, Ulrich LE, Zhulin IB. 2020. MiST 3.0: an updated microbial signal transduction database with an emphasis on chemosensory systems. Nucleic Acids Res 48:D459–D464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy KC, Campellone KG. 2003. Lambda Red-mediated recombinogenic engineering of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic E. coli. BMC Mol Biol 4:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López S, Prieto M, Dijkstra J, Dhanoa MS, France J. 2004. Statistical evaluation of mathematical models for microbial growth. Int J Food Microbiol 96:289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez JJ, Mulvey MA, Schilling JD, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ. 2000. Type 1 pilus-mediated bacterial invasion of bladder epithelial cells. EMBO J 19:2803–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hung CS, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ. 2009. A murine model of urinary tract infection. Nat Protoc 4:1230–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannan TJ, Mysorekar IU, Hung CS, Isaacson-Schmid ML, Hultgren SJ. 2010. Early severe inflammatory responses to uropathogenic E. coli predispose to chronic and recurrent urinary tract infection. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane MC, Lockatell V, Monterosso G, Lamphier D, Weinert J, Hebel JR, Johnson DE, Mobley HL. 2005. Role of motility in the colonization of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the urinary tract. Infect Immun 73:7644–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berg HC. 2017. The flagellar motor adapts, optimizing bacterial behavior. Protein Sci 26:1249–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brannon JR, Dunigan T, Beebout C, Ross T, Reynolds WS, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2020. Invasion of Vaginal Epithelial Cells by Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Nature Communication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spaulding CN, Klein RD, Ruer S, Kau AL, Schreiber HL, Cusumano ZT, Dodson KW, Pinkner JS, Fremont DH, Janetka JW, Remaut H, Gordon JI, Hultgren SJ. 2017. Selective depletion of uropathogenic E. coli from the gut by a FimH antagonist. Nature 546:528–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beebout CJ, Robertson GL, Reinfeld BI, Blee AM, Morales GH, Brannon JR, Chazin WJ, Rathmell WK, Rathmell JC, Gama V, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2022. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli subverts mitochondrial metabolism to enable intracellular bacterial pathogenesis in urinary tract infection. Nat Microbiol 7:1348–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mika F, Hengge R. 2005. A two-component phosphotransfer network involving ArcB, ArcA, and RssB coordinates synthesis and proteolysis of sigmaS (RpoS) in E. coli. Genes Dev 19:2770–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Constantinidou C, Hobman JL, Griffiths L, Patel MD, Penn CW, Cole JA, Overton TW. 2006. A reassessment of the FNR regulon and transcriptomic analysis of the effects of nitrate, nitrite, NarXL, and NarQP as Escherichia coli K12 adapts from aerobic to anaerobic growth. J Biol Chem 281:4802–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prost LR, Miller SI. 2008. The Salmonellae PhoQ sensor: mechanisms of detection of phagosome signals. Cell Microbiol 10:576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soncini FC, Groisman EA. 1996. Two-component regulatory systems can interact to process multiple environmental signals. J Bacteriol 178:6796–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beebout CJ, Sominsky LA, Eberly AR, Van Horn GT, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2021. Cytochrome bd promotes Escherichia coli biofilm antibiotic tolerance by regulating accumulation of noxious chemicals. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malpica R, Franco B, Rodriguez C, Kwon O, Georgellis D. 2004. Identification of a quinone-sensitive redox switch in the ArcB sensor kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:13318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Georgellis D, Kwon O, Lin EC. 2001. Quinones as the redox signal for the arc two-component system of bacteria. Science 292:2314–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serra DO, Richter AM, Hengge R. 2013. Cellulose as an architectural element in spatially structured Escherichia coli biofilms. J Bacteriol 195:5540–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serra DO, Hengge R. 2021. Bacterial Multicellularity: The Biology of. Annu Rev Microbiol 75:269–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Brien VP, Dorsey DA, Hannan TJ, Hultgren SJ. 2018. Host restriction of Escherichia coli recurrent urinary tract infection occurs in a bacterial strain-specific manner. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hannan TJ, Roberts PL, Riehl TE, van der Post S, Binkley JM, Schwartz DJ, Miyoshi H, Mack M, Schwendener RA, Hooton TM, Stappenbeck TS, Hansson GC, Stenson WF, Colonna M, Stapleton AE, Hultgren SJ. 2014. Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 Prevents Chronic and Recurrent Cystitis. EBioMedicine 1:46–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwan WR. 2009. Survival of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the murine urinary tract is dependent on OmpR. Microbiology (Reading) 155:1832–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Debnath I, Norton JP, Barber AE, Ott EM, Dhakal BK, Kulesus RR, Mulvey MA. 2013. The Cpx stress response system potentiates the fitness and virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun 81:1450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palaniyandi S, Mitra A, Herren CD, Lockatell CV, Johnson DE, Zhu X, Mukhopadhyay S. 2012. BarA-UvrY two-component system regulates virulence of uropathogenic E. coli CFT073. PLoS One 7:e31348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kostakioti M, Hadjifrangiskou M, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ. 2009. QseC-mediated dephosphorylation of QseB is required for expression of genes associated with virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 73:1020–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park DM, Akhtar MS, Ansari AZ, Landick R, Kiley PJ. 2013. The bacterial response regulator ArcA uses a diverse binding site architecture to regulate carbon oxidation globally. PLoS Genet 9:e1003839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cotter PA, Melville SB, Albrecht JA, Gunsalus RP. 1997. Aerobic regulation of cytochrome d oxidase (cydAB) operon expression in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA in repression and activation. Mol Microbiol 25:605–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Compan I, Touati D. 1994. Anaerobic activation of arcA transcription in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA. Mol Microbiol 11:955–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown AN, Anderson MT, Bachman MA, Mobley HLT. 2022. The ArcAB Two-Component System: Function in Metabolism, Redox Control, and Infection. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 86:e0011021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Filippou PS, Kasemian LD, Panagiotidis CA, Kyriakidis DA. 2008. Functional characterization of the histidine kinase of the E. coli two-component signal transduction system AtoS-AtoC. Biochim Biophys Acta 1780:1023–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leblanc SK, Oates CW, Raivio TL. 2011. Characterization of the induction and cellular role of the BaeSR two-component envelope stress response of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 193:3367–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alvarez AF, Rodríguez C, González-Chávez R, Georgellis D. 2021. The Escherichia coli two-component signal sensor BarA binds protonated acetate via a conserved hydrophobic-binding pocket. J Biol Chem 297:101383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vilhena C, Kaganovitch E, Shin JY, Grünberger A, Behr S, Kristoficova I, Brameyer S, Kohlheyer D, Jung K. 2018. A Single-Cell View of the BtsSR/YpdAB Pyruvate Sensing Network in Escherichia coli and Its Biological Relevance. J Bacteriol 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raivio TL, Silhavy TJ. 1997. Transduction of envelope stress in Escherichia coli by the Cpx two-component system. J Bacteriol 179:7724–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cariss SJ, Tayler AE, Avison MB. 2008. Defining the growth conditions and promoter-proximal DNA sequences required for activation of gene expression by CreBC in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 190:3930–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munson GP, Lam DL, Outten FW, O’Halloran TV. 2000. Identification of a copper-responsive two-component system on the chromosome of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 182:5864–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheu PD, Liao YF, Bauer J, Kneuper H, Basché T, Unden G, Erker W. 2010. Oligomeric sensor kinase DcuS in the membrane of Escherichia coli and in proteoliposomes: chemical cross-linking and FRET spectroscopy. J Bacteriol 192:3474–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheung WD, Hart GW. 2008. AMP-activated protein kinase and p38 MAPK activate O-GlcNAcylation of neuronal proteins during glucose deprivation. J Biol Chem 283:13009–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaspar S, Bott M. 2002. The sensor kinase CitA (DpiB) of Escherichia coli functions as a high-affinity citrate receptor. Arch Microbiol 177:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hall MN, Silhavy TJ. 1981. Genetic analysis of the ompB locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol 151:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sen H, Aggarwal N, Ishionwu C, Hussain N, Parmar C, Jamshad M, Bavro VN, Lund PA. 2017. Structural and Functional Analysis of the Escherichia coli Acid-Sensing Histidine Kinase EvgS. J Bacteriol 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ninfa AJ, Magasanik B. 1986. Covalent modification of the glnG product, NRI, by the glnL product, NRII, regulates the transcription of the glnALG operon in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:5909–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schramke H, Tostevin F, Heermann R, Gerland U, Jung K. 2016. A Dual-Sensing Receptor Confers Robust Cellular Homeostasis. Cell Rep 16:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gushchin I, Aleksenko VA, Orekhov P, Goncharov IM, Nazarenko VV, Semenov O, Remeeva A, Gordeliy V. 2021. Nitrate- and Nitrite-Sensing Histidine Kinases: Function, Structure, and Natural Diversity. Int J Mol Sci 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheung J, Hendrickson WA. 2009. Structural analysis of ligand stimulation of the histidine kinase NarX. Structure 17:190–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Groisman EA. 2001. The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ. J Bacteriol 183:1835–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ernst RK, Guina T, Miller SI. 1999. How intracellular bacteria survive: surface modifications that promote resistance to host innate immune responses. J Infect Dis 179 Suppl 2:S326–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wanner BL, Chang BD. 1987. The phoBR operon in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol 169:5569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kato S, Han SY, Liu W, Otsuka K, Shibata H, Kanamaru R, Ishioka C. 2003. Understanding the function-structure and function-mutation relationships of p53 tumor suppressor protein by high-resolution missense mutation analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:8424–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clarke MB, Hughes DT, Zhu C, Boedeker EC, Sperandio V. 2006. The QseC sensor kinase: a bacterial adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:10420–10425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Francez-Charlot A, Laugel B, Van Gemert A, Dubarry N, Wiorowski F, Castanié-Cornet MP, Gutierrez C, Cam K. 2003. RcsCDB His-Asp phosphorelay system negatively regulates the flhDC operon in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 49:823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moore JO, Hendrickson WA. 2012. An asymmetry-to-symmetry switch in signal transmission by the histidine kinase receptor for TMAO. Structure 20:729–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Verhamme DT, Arents JC, Postma PW, Crielaard W, Hellingwerf KJ. 2001. Glucose-6-phosphate-dependent phosphoryl flow through the Uhp two-component regulatory system. Microbiology (Reading) 147:3345–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Urano H, Umezawa Y, Yamamoto K, Ishihama A, Ogasawara H. 2015. Cooperative regulation of the common target genes between H₂O₂-sensing YedVW and Cu²⁺-sensing CusSR in Escherichia coli. Microbiology (Reading) 161:729–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taher R, de Rosny E. 2021. A structure-function study of ZraP and ZraS provides new insights into the two-component system Zra. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj 1865:129810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bougdour A, Wickner S, Gottesman S. 2006. Modulating RssB activity: IraP, a novel regulator of sigma(S) stability in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev 20:884–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee AK, Falkow S. 1998. Constitutive and inducible green fluorescent protein expression in Bartonella henselae. Infect Immun 66:3964–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DePas WH. 2014. Characterization of the Structure, Regulation, and Function of CsgD mediated Escherichia coli Biofilms. Doctor of Philosophy. University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Floyd KA, Moore JL, Eberly AR, Good JA, Shaffer CL, Zaver H, Almqvist F, Skaar EP, Caprioli RM, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2015. Adhesive fiber stratification in uropathogenic Escherichia coli biofilms unveils oxygen-mediated control of type 1 pili. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hurst MN, Beebout CJ, Mersfelder R, Hollingsworth A, Guckes KR, Bermudez T, Floyd KA, Reasoner SA, Williams D, Hadjifrangiskou M. 2020. A Bacterial Signaling Network Controls Antibiotic Resistance by Regulating Anaplerosis of 2-oxoglutarate. bioRxiv:2020.10.22.351270. [Google Scholar]