Abstract

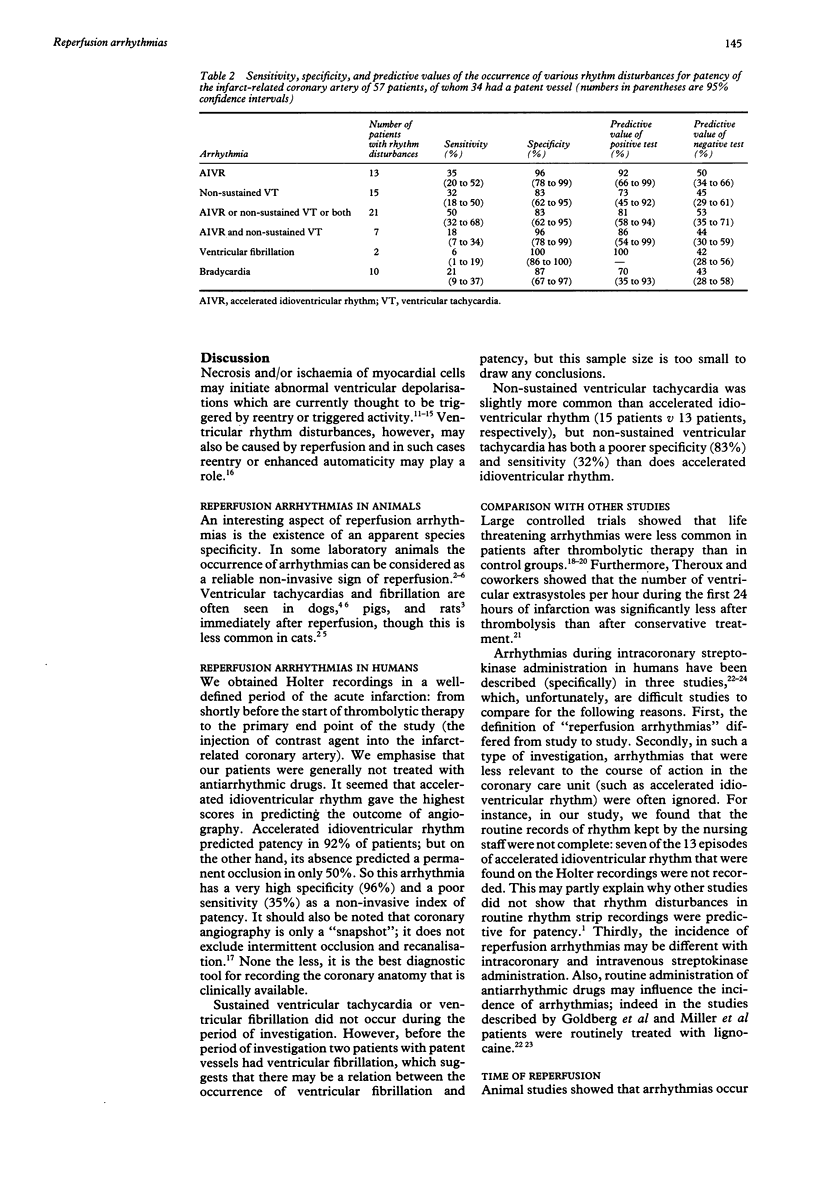

In animal studies reperfusion of coronary arteries is commonly accompanied by ventricular arrhythmias. It is not certain, however, whether ventricular arrhythmias can be used as a reliable non-invasive marker of reperfusion in humans. Two-channel Holter recordings were obtained from the start of an intravenous infusion of streptokinase until coronary angiography (2.8 (2.7) hours (mean SD)) afterwards) in 57 patients with acute myocardial infarction of less than four hours who were generally not treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. Ventricular arrhythmias occurred in 21 (37%) of the 57 patients: accelerated idioventricular rhythm in 13 patients and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in 15 patients. Seven patients had both accelerated idioventricular rhythm and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. Coronary angiography showed a patent infarct-related vessel in 12 (92%) of the 13 patients with accelerated idioventricular rhythm (95% confidence interval 66 to 99%), in 22 (50%) of the 44 patients without accelerated idioventricular rhythm (95% CI 34 to 66%), in 11 (73%) of the 15 patients with non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (95% CI 45 to 92%), and in 23 (55%) (95% CI 39 to 71%) of the 42 patients who did not have non-sustained ventricular tachycardia. Seventeen (81%) of the 21 patients with accelerated idioventricular rhythm, or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, or both, had a patent infarct-related vessel (95% CI 58 to 94%) as did 17 (47%) of the 36 patients with no ventricular arrhythmia (95% CI 29 to 65%). In patients with accelerated idioventricular rhythm after thrombolysis the infarct-related vessel is almost certain to be patent; but the infarct-related coronary artery can still be patent when no arrhythmia is seen.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Califf R. M., O'Neil W., Stack R. S., Aronson L., Mark D. B., Mantell S., George B. S., Candela R. J., Kereiakes D. J., Abbottsmith C. Failure of simple clinical measurements to predict perfusion status after intravenous thrombolysis. Ann Intern Med. 1988 May;108(5):658–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-108-5-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson N., Olsson S. B. Induction of delayed repolarization during chronic beta-receptor blockade. Eur Heart J. 1985 Nov;6 (Suppl 500):163–169. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/6.suppl_d.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S., Greenspon A. J., Urban P. L., Muza B., Berger B., Walinsky P., Maroko P. R. Reperfusion arrhythmia: a marker of restoration of antegrade flow during intracoronary thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 1983 Jan;105(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackett D., Davies G., Chierchia S., Maseri A. Intermittent coronary occlusion in acute myocardial infarction. Value of combined thrombolytic and vasodilator therapy. N Engl J Med. 1987 Oct 22;317(17):1055–1059. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710223171704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B. F., Rosen M. R. Cellular mechanisms for cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res. 1981 Jul;49(1):1–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse M. J., Kléber A. G. Electrophysiological changes and ventricular arrhythmias in the early phase of regional myocardial ischemia. Circ Res. 1981 Nov;49(5):1069–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.5.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse M. J., van Capelle F. J., Morsink H., Kléber A. G., Wilms-Schopman F., Cardinal R., d'Alnoncourt C. N., Durrer D. Flow of "injury" current and patterns of excitation during early ventricular arrhythmias in acute regional myocardial ischemia in isolated porcine and canine hearts. Evidence for two different arrhythmogenic mechanisms. Circ Res. 1980 Aug;47(2):151–165. doi: 10.1161/01.res.47.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katus H. A., Diederich K. W., Scheffold T., Uellner M., Schwarz F., Kübler W. Non-invasive assessment of infarct reperfusion: the predictive power of the time to peak value of myoglobin, CKMB, and CK in serum. Eur Heart J. 1988 Jun;9(6):619–624. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A. S., Hearse D. J. Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias: mechanisms and prevention. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984 Jun;16(6):497–518. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning A. S., Hearse D. J. Reperfusion-induced arrhythmias: mechanisms and prevention. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1984 Jun;16(6):497–518. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(84)80638-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. C., Krucoff M. W., Satler L. F., Green C. E., Fletcher R. D., Del Negro A. A., Pearle D. L., Kent K. M., Rackley C. E. Ventricular arrhythmias during reperfusion. Am Heart J. 1986 Nov;112(5):928–932. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(86)90302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M., Mead L. A., Kwiterovich P. O., Jr, Pearson T. A. Dyslipidemias with desirable plasma total cholesterol levels and angiographically demonstrated coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Jan 1;65(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90017-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd S. M., Corr P. B. Electrophysiologic mechanisms underlying arrhythmias due to reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1987 Aug;76(2):404–426. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan F. H., Braunwald E., Canner P., Dodge H. T., Gore J., Van Natta P., Passamani E. R., Williams D. O., Zaret B. The effect of intravenous thrombolytic therapy on left ventricular function: a report on tissue-type plasminogen activator and streptokinase from the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI Phase I) trial. Circulation. 1987 Apr;75(4):817–829. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan F. H., Epstein S. E. Effects of calcium channel blocking agents on reperfusion arrhythmias. Am Heart J. 1982 Jun;103(6):973–977. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(82)90559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoons M. L., Serruys P. W., vd Brand M., Bär F., de Zwaan C., Res J., Verheugt F. W., Krauss X. H., Remme W. J., Vermeer F. Improved survival after early thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. A randomised trial by the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute in The Netherlands. Lancet. 1985 Sep 14;2(8455):578–582. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90584-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théroux P., Morissette D., Juneau M., de Guise P., Pelletier G., Waters D. D. Influence of fibrinolysis and percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty on the frequency of ventricular premature complexes. Am J Cardiol. 1989 Apr 1;63(12):797–801. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuanetti G., Vanoli E., Zaza A., Priori S., Stramba-Badiale M., Schwartz P. J. Lack of correlation between occlusion and reperfusion arrhythmias in the cat. Am Heart J. 1985 May;109(5 Pt 1):932–936. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemel N. M., Swenne C. A., Robles de Medina E. O. Assessment of mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias from the surface ECG in 118 patients. Eur Heart J. 1987 Aug;8(8):813–820. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]