Abstract

Objective:

To identify genetic factors that may modify the effects of the MAPT locus in Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods:

We used data from the International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC) and the UK biobank (UKBB). We stratified the IPDGC cohort for carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (PD patients n=8,492 and controls n=6,765) and carriers of the H2 haplotype (with either H1/H2 or H2/H2 genotypes, patients n=4,779 and controls n=4,849) to perform genome-wide association studies (GWASs). Then, we performed replication analyses in the UKBB data. To study the association of rare variants in the new nominated genes, we performed burden analyses in two cohorts (Accelerating Medicines Partnership – Parkinson Disease and UKBB) with a total sample size PD patients n=2,943 and controls n=18,486.

Results:

We identified a novel locus associated with PD among MAPT H1/H1 carriers near EMP1 (rs56312722, OR=0.88, 95%CI= 0.84–0.92, p= 1.80E-08), and a novel locus associated with PD among MAPT H2 carriers near VANGL1 (rs11590278, OR=1.69 95%CI=1.40–2.03, p=2.72E-08). Similar analysis of the UKBB data did not replicate these results and rs11590278 near VANGL1 did have similar effect size and direction in carriers of H2 haplotype, albeit not statistically significant (OR= 1.32, 95%CI= 0.94–1.86, p=0.17). Rare EMP1 variants with high CADD scores were associated with PD in the MAPT H2 stratified analysis (p=9.46E-05), mainly driven by the p.V11G variant.

Interpretation:

We identified several loci potentially associated with PD stratified by MAPT haplotype and larger replication studies are required to confirm these associations.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, genetics, MAPT, EMP1, VANGL1, GWAS

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder with complex genetic background, neuropathology, and clinical features. It is possible that what we define today as PD, which is based on clinical presentation only, is a combination of multiple disorders with different etiologies and pathologies but with similar clinical phenotype.1 PD is often categorized as an alpha-synucleinopathy, due to the typical accumulation of alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies and Lewy neuritis.2 However, other pathologies such as tau pathology are also common in PD, as ~50% of PD patients also show tau accumulation and deposition.3 In specific genetic subtypes of PD, such as LRRK2-associated PD, alpha-synuclein pathology can be found in only ~50% of the cases,4 whereas tau pathology can be abundant in more than 90% of patients.5 In six brains from PD patients with the LRRK2 p.I2020T mutation, only one had alpha-synucleinopathy, while tau pathology was very common.6 In contrast to LRRK2, in GBA1-associated PD, alpha-synuclein accumulation is very common, found in nearly all patients with GBA1 variants, and tau pathology is likely less common.7 These genetic-neuropathological differences may suggest that tau is associated with specific genetic subtypes/variants.

Tau is encoded by MAPT (microtubule associated protein tau), a gene associated with multiple neurological disorders, including PD.8 The association with PD is mediated by the H1 and H2 MAPT haplotypes, created by an inversion of a large genomic region around MAPT.9 The H1 haplotype is the most common haplotype and H2 is more rare and absent in non-Caucasian populations.10 In PD, the H1 haplotype is associated with an increased risk of PD, whereas the H2 haplotype is associated with a reduced PD risk.8 The H1 haplotype and specific subhaplotypes have been linked to more severe tau pathology or increased tau expression in some neurodegenerative diseases,11–13 but whether or not these haplotypes affect tau pathology in PD is unclear. Recently, MAPT stratified analysis was done for Alzheimer’s disease,14 demonstrating potential novel loci and interactions.

Since MAPT encodes tau, which is found in brains of many PD patients, but with differential distribution in different genetic subtypes (e.g. LRRK2 and GBA1), and since MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes are associated with PD, we hypothesized that some genetic variants may be either more or less important in carriers of these haplotypes. To test this hypothesis, we performed stratified genome-wide association studies (GWAS) separately analyzing carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (PD patients n=8,492 and controls n=6,765) and carriers of the H2 haplotype (PD patients n=4,779 and controls n=4,849). We then examined whether specific variants are associated with PD in one of the genetically defined groups, but not in the other. To study the association of rare variants in the new nominated genes, we performed burden analyses in two cohorts with a total sample size PD patients n=2,943 and controls n=18,486.

Methods:

Population and stratification

Our study included a total of 13,271 PD patients and 11,614 controls of European ancestry from the International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC) with available sex, age and principal components data. Details on the cohorts composing the IPDGC data can be found in Supplementary Table 1. To stratify by MAPT haplotype, we used the H2-tagging single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs8070723 as previously reported. Carriers of the SNP rs8070723 are carriers of the H2 haplotype (with a genotype of either H1/H2 or H2/H2, PD patients n=4,779 and controls n=4,849), and non-carriers of this variant are carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (PD patients n=8,442 and controls n=6,765). The SNP rs8070723 is in high linkage disequilibrium (D’=1, r2=0.65) with the top SNP in the PD GWAS in the MAPT locus (rs62053943).

To study the role of rare variants in genes potentially interacting with MAPT from the previous analyses, we used whole genome and whole exome sequencing data from two cohorts: the Accelerating Medicines Partnership – Parkinson Disease (AMP-PD, 2.5 release; PD patients n=2,341 and controls n=3,486), and the UK biobank (UKBB; PD patients n=602 and controls n=15,000). The AMP-PD cohorts are detailed in the acknowledgments. We then stratified selected cohorts for rare variant analysis by MAPT haplotype, including H2 haplotype carriers (PD patients n=215, controls n=6,081 for UKBB and PD patients n=786, controls n=1,438 for AMP-PD) and H1/H1 haplotype carriers (PD patients n=387, controls n=8,919 for UKBB and PD patients n=1,555, controls n=2,048 for AMP-PD).

Quality control and genome-wide association studies

Quality control procedures were performed for IPDGC genotyping data on individual and variant-level as previously described.15 Two case-control GWASs were performed using logistic regression in plink 1.9, including SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) of > 0.01.16 We applied sex, age, and 10 principal components (PC) as covariates. One GWAS compared PD patients and controls who carry the MAPT H2 haplotype, and the second GWAS compared PD patients and controls who carry the H1/H1 genotype. We calculated genomic inflation factor (λ) for GWASs in both cohorts. To account for the impact of sample size, we scaled the λ values to 1000 cases and 1000 controls (λ1000) and created Quantile-Quantile plots as previously described.17 SNPs that surpass the Bonferroni threshold for genome-wide studies (5.0 × 10−8) were considered statistically significant. We created mirror Miami plots representing GWASs for carriers and non-carriers using the Hudson package in R (https://github.com/anastasia-lucas/hudson). Independent SNPs and loci were defined using the functional mapping and annotation portal (FUMA).18 To visually compare the effect size between carriers and non-carriers of the H2 haplotype, we constructed a beta-beta plot comparing the effect sizes in the two GWASs.

Variants with a difference of >5 fold in effect size were selected for further interaction analyses. We then examined whether interaction exists between the H2-tagging SNP rs8070723 and the SNPs that demonstrated differential effect sizes in the two GWASs. This analysis was done using plink and TLTO (Two-loci to OR) from VARI3 package.19

To replicate these potential interactions, we used the UK biobank data and performed stratification analysis followed by interaction analysis. Participants of European ancestry were selected from data field 22006. Heterozygosity outliers, samples with high missingness rates and samples with sex chromosome aneuploidy according to data field 22027/22019 were also excluded. The cohort also underwent filtration for relatedness using Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis (GCTA) with a threshold of 0.125.20 In total, we included 344,597 unrelated participants of European origin, carriers of the H2 haplotype (PD patients n=550 and controls n=138,292), and carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (PD patients n=1,004 and controls n=204,749). The power to replicate results in UKBB was calculated using Genetic Association Study (GAS) power calculator.21 Locus zoom plots for regions of interest have been made using the online tool http://locuszoom.org/.22

Rare variants burden analysis

We then studied rare variants in the novel genes that were nominated in the MAPT stratified GWASs. We performed quality control for whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing data using standard procedures on individual and variant levels as previously described.23, 24 Annotation was performed using ANNOVAR25 with Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score reference,26 where variants with a CADD score ≥20 represent the top 1% of potentially deleterious variants. In this analysis, we only included variants with MAF <0.01. To perform burden analysis, we used an optimized sequence Kernel association test (SKAT-O and metaSKAT, R package).27, 28 Separate analyses were done for nonsynonymous variants and variants with high CADD score with adjustment for sex and age.

Results

Identification of variants associated with carriers and non-carriers of the MAPT H2 haplotype

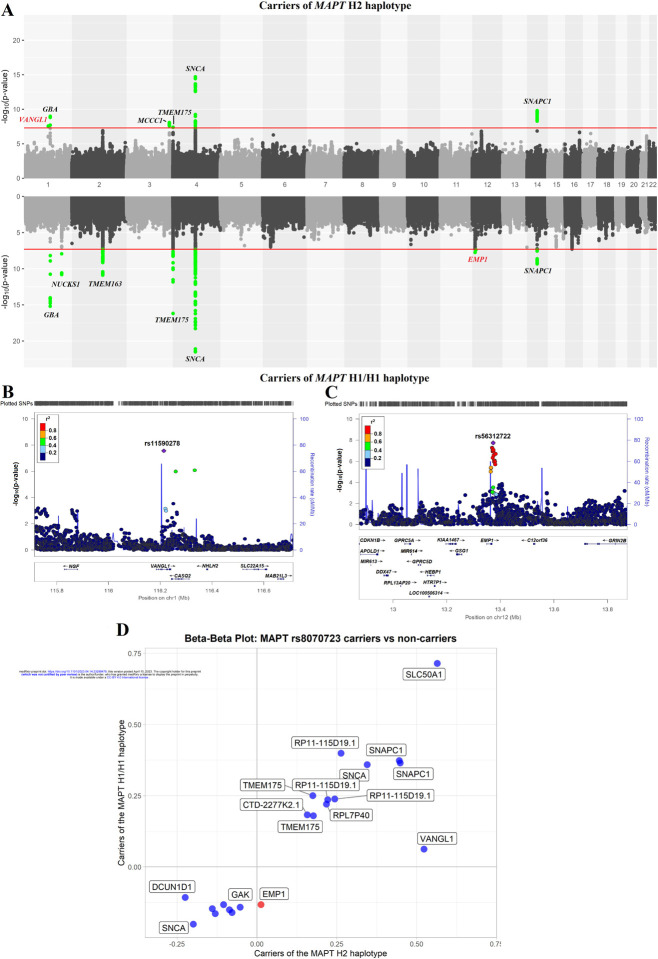

To examine whether specific genetic variants are associated with carriers or non-carriers of the MAPT H2 haplotype, we performed two stratified GWASs. One GWAS included only H1/H1 genotype carriers (PD patients n=8,492 and controls n=6,765) and the second GWAS included carriers of either H1/H2 or H2/H2 genotypes, (PD patients n=4,779 and controls n=4,849). The genomic inflation values for H1 haplotype GWAS and H2/H2 haplotype GWAS were λ = 1.17 and λ = 1.11, respectively. When the genomic inflation was scaled to 1,000 cases and 1,000 controls for both cohorts, the values were the same, with λ1000=1.02 (Supplementary Figure 1). Overall, we identified seven loci in the MAPT H1/H1-stratified GWAS and six loci in the MAPT H2-stratified GWAS (Table 1, Figure 1A). In the MAPT H2-stratified GWAS, on top of known PD GWAS loci, we identified a novel locus associated with PD among carriers, tagged by rs11590278 (near VANGL1, OR=1.69, 95%CI=1.40–2.03, p=2.72E-08; Figure 1B). This SNP was not associated with PD in the H1/H1 stratified analysis (OR=1.06, 95%CI= 0.92–1.23, p=0.40). In the MAPT H1/H1-stratified GWAS we also identified a novel locus associated with PD in H1/H1 carriers, tagged by rs56312722 (near EMP1, OR=0.88, 95%CI= 0.84–0.92, p=1.80E-08; Figure 1C). This SNP was not associated with PD in the H2 stratified analysis (OR= 1.01, 95%CI= 0.96–1.07, p= 0.66). We also identified a novel locus in SNAPC1, which was significant in both carriers of H1/H1 haplotype rs113697492 (OR= 1.45, 95%CI= 1.29–1.63, p= 4.70E-10) and H2 haplotype rs75302411 (OR= 1.57, 95%CI= 1.37–1.80, p= 1.58E-10). Thus, this association was unrelated to haplotype subtyping. We did not find any effect of the novel loci from the MAPT stratified GWAS on age-at-onset of PD (Supplementary Table 2). Of the known PD loci, GBA1, SNCA and TMEM175 were identified in both GWASs. The NUCKS1 and TMEM163 loci were associated with PD with the MAPT H1/H1 genotype, but not associated with PD with the H2 haplotype. Since the GWAS of the H1/H1 genotype is larger, this could be attributed to reduced power of the H2 haplotype GWAS, although the beta of the NUCKS1 locus was more than two-fold larger in the H1/H1 genotype carriers compared to H2 haplotype carriers (−0.161 vs. −0.078, respectively). Similarly, the MCCC1 locus was only associated with PD among carriers of the H2 haplotype, but not among carriers of the H1/H1. The beta for the SNP tagging the MCCC1 locus, rs9858038, was more than two-fold larger in carriers of the H2 haplotype compared to carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (‒20.224 vs. ‒0.108, respectively).

Table 1.

Significant loci in MAPT stratified GWAS.

| Carriers of the MAPT H1/H1 haplotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Effect allele | Closest gene or PD locus | p | beta | SE | OR (95%, Cl) | MAF | known PD locus |

| rs 12726330 | A | GBA1 | 6.43E-16 | 0.715 | 0.09 | 2.04 (1.72–2.43) | 0.21 | Yes |

| rs823118 | C | NUCKS1 | 1.55E-11 | −0.161 | 0.02 | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 0.42 | Yes |

| rs6753334 | G | TMEM163 | 1.30E-11 | −0.165 | 0.02 | 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | 0.43 | Yes |

| rs34311866 | C | TMEM175 | 6.48E-17 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) | 0.20 | Yes |

| rs356219 | G | SNCA | 3.16E-22 | 0.236 | 0.02 | 1.27 (1.21–1.33) | 0.40 | Yes |

| rs56312722 | T | EMP1 | 1.S0E-0S | −0.133 | 0.02 | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 0.50 | No |

| rsll3697492 | A | SNAPC1 | 4.70E-10 | 0.373 | 0.06 | 1.45 (1.29–1.63) | 0.04 | No |

| Carriers of the MAPT H2 Laplotype | ||||||||

| SNP | Effect allele | Closest gene or PD locus | p | beta | SE | OR (95%, Cl) | MAF | known PD locus |

| rsll590278 | C | VANGL1 | 2.72E-08 | 0.52 | 0.23 | 1.69 (1.40–2.03) | 0.03 | No |

| rsl45330152 | C | GBA1 | 1.03E-09 | 0.75 | 0.12 | 2.12 (1.67–2.70) | 0.02 | Yes |

| rs9858038 | A | MCCC1 | 8.33E-09 | −0.22 | 0.04 | 0.80 (0.74–0.86) | 0.18 | Yes |

| rs6599388 | T | TMEM175 | 4.02E-08 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 1.19 (1.12–1.27) | 0.31 | Yes |

| rs356182 | G | SNCA | 1.98E-15 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 1.28 (1.20–1.36) | 0.36 | Yes |

| rs75302411 | T | SNAPC1 | 1.58E-10 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 1.57 (1.37–1.80) | 0.05 | No |

GWAS- genome wide association study, OR- odds ratio, CI- confidence interval, SE- standard error, SNP- single nucleotide polymorphism, PD- Parkinson’s disease, L95- Lower bound of 95% confidence interval for odds ratio U95 Upper- bound of 95% confidence interval for odds ratio, MAF- minor allele frequency. Novel loci are in bold

Figure 1.

A. Miami plot of carriers (top) and non-carriers (bottom) of MAPT H2 haplotype of selected variants. The red line indicates GWAS significance threshold. Green dots indicate passing the threshold variants. New loci with potential interaction with MAPT highlighted in red, other loci highlighted in black. B. Locus zoom plot of VANGL1 variants (+/− 500kb) in the stratified PD risk GWAS of the MAPT H2 haplotype carriers. C. Locus zoom plot of EMP1 variants (+/− 500kb) in the stratified PD risk GWAS of the MAPT H1/H1 haplotype carriers. The position of the variants on the chromosome (x axis) is plotted against the log10-scaled p-values (left y axis). SNP with the smallest p-value is indicated by a purple diamond. Linkage disequilibrium scores related to the top variant are defined by different colors, explained by the legend on the upper left corner. The right vertical axis indicates the regional recombination rate (cM/Mb). Abbreviations: chr, chromosome; cM, centimorgan; Mb, Megabase; PD, Parkinson’s disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism. D. Beta-beta plots for independent SNPs that reached genome wide association level of significance in carriers or non-carriers of MAPT rs8070723 (Carriers of the MAPT H2 haplotype vs carriers of the MAPT H1/H1 haplotype). Red circles denote SNPs with effect size (beta) difference of more than 5 times between carriers of MAPT H2 haplotype and carriers of the MAPT H1/H1 haplotype.

We attempted to replicate these results, specifically the novel loci, in the UKBB data, stratified by carriers and non-carriers of the MAPT H2 haplotype. Considering the number of MAPT haplotype carriers, allele frequency and effect size of novel loci, we calculated the statistical power for replication. We did not have sufficient power to replicate neither rs11590278 (60%) nor rs56312722 (54%) and as expected both associations did not reach statistical significance in the UKBB. However, the SNP rs11590278 near VANGL1 had similar effect direction in carriers of H2 haplotype (OR= 1.32, 95%CI= 0.94–1.86, p=0.17). The SNP rs56312722 near EMP1 had different direction of effect in carriers of H1/H1 haplotype (OR= 1.07, 95%CI= 0.97–1.16, p= 0.10).

Interaction analysis of MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes with SNPs in the VANGL1 and EMP1 loci

To identify SNPs for interaction analyses with the MAPT H2-tagging SNP rs8070723, we generated a beta-beta plot (Figure 1D). We selected independent SNPs that had an effect size (beta) >5-fold larger in one GWAS compared to the other and were significant in the GWAS level in one of the two GWASs. The SNP rs11590278 (VANGL1) had an 8-fold difference in effect size when comparing MAPT H2 haplotype carriers and H1/H1 genotype carriers (b=0.52, p=2.72E-08 vs b=0.062, p=0.4, respectively). The SNP rs56312722 (EMP1) had a ten-fold difference in beta compared to H2 haplotype carriers (b=0.133, p=1.80E-08 vs b=0.013, p=0.6582, respectively).

We then performed allele-specific interaction in a stratified cohort between MAPT H2-tagging SNP rs8070723 and the SNPs of interest (rs11590278 VANGL1 and rs56312722 EMP1; Table 2). We found that C/T allele of rs11590278 (VANGL1) interacted with H1/H2 MAPT haplotype (OR=1.73, 95%CI=1.40–2.18, p=9.93E-08). The direction of the effect was preserved in the UKBB data but without statistical significance (OR=1.40, 95%CI=0.94–2.01, p=0.083). In the subsequent analysis, we found an interaction between rs56312722 EMP1 T/T genotype and MAPT H1/H1 haplotype (OR=0.84, 95%CI=0.78–0.91, p=5.34E-06). This interaction was not replicated in UKBB (OR=1.12, 95%CI=0.97–1.30, p=0.101).

Table 2.

Allele specific interaction between MAPT H2-tagging SNP rs8070723 two new loci (rs11590278 VANGL1 and rs56312722 EMP1)

| SNPs interaction | IPDGC cohort | UKBB cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | ||

| Interaction of rs11590278 (VANGL1) vs H2 MAPT haplotype | |||||

| rs11590278 (VANGL1) | rs8070723 (MAPT) | N (PD) = 4,779 N (controls) = 4,849 | N (PD) = 550 N (controls) = 138,292 | ||

| C/C | G/G | N/A | 1 | 22.91 (0.53–157.71) | 0.057 |

| C/T | G/G | 1.51 (0.97–2.4) | 0.067 | 0.58 (0.07–2.10) | 0.593 |

| T/T | G/G | 0.85 (0.75–0.96) | 0.008 | 0.93 (0.70–1.21) | 0.603 |

| C/C | G/A | 5.08 (0.57–239.93) | 0.122 | N/A | 1 |

| C/T | G/A | 1.73 (1.40–2.18) | 9.93E-08 | 1.40 (0.94–2.01) | 0.083 |

| T/T | G/A | 0.94 (0.84–1.04) | 0.225 | 0.97 (0.78–1.21) | 0.738 |

| Interaction of rs11590278 (VANGL1) vs H1/H1 MAPT haplotype | |||||

| rs11590278 (VANGL1) | rs8070723 (MAPT) | N (PD) = 8,442 N (controls) = 6,765 | N (PD) = 1,004 N (controls) = 204,749 | ||

| C/C | A/A | 1.12 (0.38–4.08) | 0.800 | 3.09 (0.37–11.43) | 0.140 |

| C/T | A/A | 1.1 (0.95–1.28) | 0.218 | 0.89 (0.64–1.21) | 0.505 |

| T/T | A/A | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 0.208 | 1.05 (0.8–1.41) | 0.786 |

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | ||

| Interaction of rs56312722 (EMP1) vs H2 MAPT haplotype | |||||

| rs56312722 (EMP1) | rs8070723 (MAPT) | N (PD) = 4,779 N (controls) = 4,849 | N (PD) = 550 N (controls) = 138,292 | ||

| T/T | G/G | 0.79 (0.62–1.01) | 0.054 | 1.19 (0.72–1.86) | 0.456 |

| T/C | G/G | 0.98 (0.83–1.16) | 0.837 | 0.87 (0.59–1.26) | 0.541 |

| C/C | G/G | 0.83 (0.66–1.06) | 0.131 | 0.81 (0.45–1.34) | 0.477 |

| T/T | G/A | 1.07 (0.97–1.19) | 0.157 | 1.13 (0.92–1.38) | 0.240 |

| T/C | G/A | 0.99 (0.92–1.08) | 0.918 | 1.01 (0.85–1.2) | 0.897 |

| C/C | G/A | 1.01 (0.92–1.12) | 0.751 | 0.91 (0.73–1.12) | 0.411 |

| Interaction of rs56312722 (EMP1) vs H1/H1 MAPT haplotype | |||||

| rs56312722 (EMP1) | rs8070723 (MAPT) | N (PD) = 8,442 N (controls) = 6,765 | N (PD) = 1,004 N (controls) = 204,749 | ||

| T/T | A/A | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | 5.34E-06 | 1.12 (0.97–1.3) | 0.101 |

| T/C | A/A | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | 0.122 | 0.96 (0.82–1.06) | 0.297 |

| C/C | A/A | 1.27 (1.18–1.37) | 1.80E-10 | 0.95 (0.82–1.1) | 0.562 |

IPDGC- International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium; UKBB – UK biobank, OR- odds ratio; 95%CI- 95% confidence interval for odds ratio; rs8070723 is a MAPT H2-tagging SNP. G/G- H2/H2 haplotype; A/A - H1/H1 haplotype; G/A - H2/H1. N/A- the results are not valid due to the lack of a sufficient number of alleles for analysis.

Rare variant analysis further suggests an association of EMP1 with Parkinson’s disease

To examine whether rare variants in EMP1 and VANGL1 play any role in PD, we performed burden analysis of variants with MAF<0.01. We found that rare variants with CADD score >20 were associated with PD in the meta-analysis of AMP-PD and UKBB cohorts (p=0.004; Supplementary Table 3). This association was driven by the UKBB cohort (p=0.0004). Moreover, after we stratified the cohorts for H2 and H1/H1 MAPT haplotypes the same way we did for the GWAS, we found that the association of EMP1 with PD was driven by the H2 haplotype carriers in both AMP-PD (p=0.018) and UKBB (p=0.004) cohorts (meta-analysis p=9.46E-05). There were only two variants with high CADD score and only the p.V11G EMP1 variant was associated with PD in the UKBB cohort (OR=8.62, 95%CI=2.21–33.61; p=0.002) and in AMP-PD (OR=5.92, 95%CI=1.12–31.14, p=0.036) in the H2 stratified cohort (Supplementary Table 4). Furthermore, p.V11G was in linkage disequilibrium with the major allele of rs56312722 in EMP1 (D’=1.0). We did not find any association between rare variants in VANGL1 and PD in any of the cohorts.

Discussion:

In the current study we performed a stratified GWAS based on the MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes, and identified three novel loci potentially associated with PD, one in carriers of the H1/H1 genotype (EMP1), one in carriers of the H2 haplotype (VANGL1), and one in both (SNAPC1). These associations were not replicated in the UKBB data, which was underpowered to detect them. We also found that rare EMP1 variants were associated with PD in H2 haplotype carriers in both cohorts (AMP-PD and UKBB). Therefore, possibly there is a complex interaction between MAPT haplotypes and the EMP1 gene, with some variants being protective for H1/H1 haplotype and causative for H2 haplotype. Additional studies are needed to examine whether the VANGL1 and EMP1 loci are indeed associated with the H2 and H1 haplotypes in PD. As for the third locus, SNAPC1, it was not identified in a much larger GWAS,15 suggesting that this could be a spurious association. However, it is also possible that methodological and/or population stratification-related issues due to inclusion of data from 23andMe masked the association in the larger GWAS. More studies are therefore needed into this locus to determine whether or not it is associated with PD.

MAPT stratified analysis has already been performed in Alzheimer’s disease,14 and an APOE-stratified GWAS has been recently performed in dementia with Lewy bodies,29 both identified potential novel loci and interactions. Together with our current work, these studies demonstrate the advantage of a stratified GWAS approach for shedding more light on the genetics of complex neurological traits with multiple potential subtypes.

In the stratified analyses by MAPT H1 and H2 haplotypes, we nominated two novel loci potentially associated with PD, near the VANGL1 and EMP1 genes. EMP1 is encoding epithelial membrane protein 1 and this gene has not previously been implicated in the pathogenesis of PD. In a recent RNA-seq study of cerebral white matter, upregulation of EMP1 was reported in multiple system atrophy patients.30 GRIN2B, located in the EMP1 locus, was previously associated with impulse control and related behaviors in PD patients.31 The MAPT H1 haplotype has been repeatedly associated with cognitive decline in PD patients.32–34 Likewise, the EMP1 locus has been previously associated with 176 traits including intelligence and cognitive performance (data retrieved from https://genetics.opentargets.org/). Thus, EMP1 could be an independent modifier of PD in MAPT H1 or H2 carriers. However, this hypothesis requires additional studies.

VANGL1 encodes the Van Gogh-like planar cell polarity protein 1 and was previously associated with neural tube defects,35, 36 but not with neurodegenerative diseases. VANGL1 is a negative regulator of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.37 Notably, Wnt signaling has been suggested to be an important factor for dopaminergic neurons homeostasis and survival.38, 39 Therefore, the involvement of VANGL1 in PD pathogenesis should also be further studied. Both genes, EMP1 and VANGL1, are expressed in brain tissues based on GTEx (data retrieved from https://www.gtexportal.org/home). However, we did not find quantitative trait loci for SNPs in EMP1 and VANGL1 associated with PD in the current study.

The KANSL1 gene has recently been nominated as potentially driving an association for the H1 haplotype at the MAPT locus.40 Additionally, it has been suggested that KANSL1 and KAT8 are two PINK1-dependent mitophagy regulators.41 In our analysis, KAT8 almost reached genome-wide association significance in the H1/H1 haplotype analysis (p=5.21E-08) and was only nominally significant in the H2 haplotype analysis (p=0.0004), with no difference in effect direction (Figure 1A). It is possible that this is due to an interaction between KAT8 and the H1 haplotype, but it could also be a power issue as the GWAS with H1/H1 carriers is much larger than H2. Therefore, further analysis is needed to determine whether KAT8 locus does indeed interact with the MAPT H1 haplotype.

Our analyses have several limitations. First, we have separated the discovery IPDGC cohort into smaller groups of carriers and non-carriers which caused imbalance in group size depending on the variant frequency and, thus, different power. We have also performed replication analyses in UKBB, which only had 550 PD H2 haplotype carries and 1,004 PD H1/H1 haplotype carriers after filtering. This makes UKBB underpowered to detect the effects seen in our discovery cohorts. Since we only studied European samples, similar studies in non-European cohorts are warranted, as well as replication of our findings in independent and larger cohorts. Another limitation is that we had several GWAS-significant loci with low MAF < 5%. Therefore, these signals require cautious interpretation and further confirmation.

To conclude, using a stratified GWAS approach, we nominated two potentially novel loci which are associated with specific MAPT gene haplotypes in PD. Our results along with previous similar studies suggest that risk loci stratification analysis could help us to genetically characterize subtypes of PD patients better and discover novel genetic associations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot for MAPT stratified GWAS. A. Q-Q plot of MAPT H1/H1 haplotype carriers B. Q-Q plot of MAPT H2 haplotype carriers.

Supplementary Table 1. Demography of studied population. Supplementary Table 2. Effect of novel SNPs EMP1 (rs56312722) and VANGL1 (rs11590278) variants on Parkinson’s disease age-at-onset in MAPT stratified cohorts. Supplementary Table 3. Burden analysis of rare EMP1 and VANGL1 variants in MAPT stratified cohorts. Supplementary Table 4. EMP1 variants with high CADD score.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the all the participants in the different cohorts. We would also like to thank all members of the International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC). See for a complete overview of members, acknowledgements, and funding http://pdgenetics.org/partners. This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 45551. This research used the NeuroHub infrastructure and was undertaken thanks in part to funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University, Calcul Québec and Compute Canada. Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the AMP PD Knowledge Platform. For up-to-date information on the study, visit https://www.amp-pd.org. AMP PD - a public-private partnership - is managed by the FNIH and funded by Celgene, GSK, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Verily. Genetic data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Fox Investigation for New Discovery of Biomarkers (BioFIND), the Harvard Biomarker Study (HBS), the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI), the Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program (PDBP), the International LBD Genomics Consortium (iLBDGC), and the STEADY-PD III Investigators. BioFIND is sponsored by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF) with support from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The BioFIND Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For up-to-date information on the study, visit michaeljfox.org/news/biofind. The HBS is a collaboration of HBS investigators [full list of HBS investigator found at https://www.bwhparkinsoncenter.org/biobank/ and funded through philanthropy and NIH and Non-NIH funding sources. The HBS Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. PPMI - a public-private partnership - is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including [list the full names of all of the PPMI funding partners found at www.ppmi-info.org/fundingpartners]. The PPMI Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org. PDBP consortium is supported by the NINDS at the National Institutes of Health. A full list of PDBP investigators can be found at https://pdbp.ninds.nih.gov/policy. The PDBP investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. Genome Sequencing in Lewy Body Dementia and Neurologically Healthy Controls: A Resource for the Research Community.” was generated by the iLBDGC, under the co-directorship by Dr. Bryan J. Traynor and Dr. Sonja W. Scholz from the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The iLBDGC Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For a complete list of contributors, please see: bioRxiv 2020.07.06.185066; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.06.185066. STEADY PD III is a 36 month, Phase 3, parallel group, placebo controlled study of the efficacy of isradipine 10 mg daily in 336 participants with early Parkinson’s Disease that was funded by the NINDS and supported by The Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Parkinson’s Study Group. The STEADY-PD III Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. The full list of STEADY PD III investigators can be found at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02168842. ZGO is supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) Chercheurs-boursiers award, and is a William Dawson Scholar. KS is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), awarded to McGill University for the Healthy Brains for Healthy Lives initiative (HBHL) and postdoctoral fellowship from FRQS. AC was supported by the Science and Technology Agency, Séneca Foundation, Comunidad Autónoma Región de Murcia, Spain through the grant 20762/FPI/18. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA). This study was financially supported by grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), awarded to McGill University for the Healthy Brains for Healthy Lives initiative (HBHL), and Parkinson Canada.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Authors have nothing to report.

Data Availability

Full code used in the analysis has been made available on git-hub (https://github.com/gan-orlab/PD_stratified_GWAS).

References:

- 1.Espay AJ, Kalia LV, Gan-Or Z, et al. Disease modification and biomarker development in Parkinson disease: revision or reconstruction? Neurology. 2020;94(11):481–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wakabayashi K, Tanji K, Odagiri S, Miki Y, Mori F, Takahashi H. The Lewy body in Parkinson’s disease and related neurodegenerative disorders. Molecular neurobiology. 2013;47:495–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, Gao F, Wang D, et al. Tau pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in neurology. 2018;9:809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalia LV, Lang AE, Hazrati L-N, et al. Clinical correlations with Lewy body pathology in LRRK2-related Parkinson disease. JAMA neurology. 2015;72(1):100–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson MX, Sengupta M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Alzheimer’s disease tau is a prominent pathology in LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease. Acta neuropathologica communications. 2019;7:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ujiie S, Hatano T, Kubo S-i, et al. LRRK2 I2020T mutation is associated with tau pathology. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2012;18(7):819–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider SA, Alcalay RN. Neuropathology of genetic synucleinopathies with parkinsonism: review of the literature. Movement Disorders. 2017;32(11):1504–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leveille E, Ross OA, Gan-Or Z. Tau and MAPT genetics in tauopathies and synucleinopathies. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2021;90:142–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zody MC, Jiang Z, Fung H-C, et al. Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21. 31 inversion region. Nature genetics. 2008;40(9):1076–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans W, Fung HC, Steele J, et al. The tau H2 haplotype is almost exclusively Caucasian in origin. Neuroscience Letters. 2004 2004/October/21/;369(3):183–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santa-Maria I, Haggiagi A, Liu X, et al. The MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with tangle-predominant dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2012. Nov;124(5):693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heckman MG, Brennan RR, Labbé C, et al. Association of MAPT Subhaplotypes With Risk of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy and Severity of Tau Pathology. JAMA Neurol. 2019. Jun 1;76(6):710–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers AJ, Pittman AM, Zhao AS, et al. The MAPT H1c risk haplotype is associated with increased expression of tau and especially of 4 repeat containing transcripts. Neurobiol Dis. 2007. Mar;25(3):561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strickland SL, Reddy JS, Allen M, et al. MAPT haplotype-stratified GWAS reveals differential association for AD risk variants. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. Jul;16(7):983–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nalls MA, Blauwendraat C, Vallerga CL, et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. The Lancet Neurology. 2019;18(12):1091–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. The American journal of human genetics. 2007;81(3):559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Bakker PI, Ferreira MA, Jia X, Neale BM, Raychaudhuri S, Voight BF. Practical aspects of imputation-driven meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Human molecular genetics. 2008;17(R2):R122–R8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, Van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nature communications. 2017;8(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cisterna-García A, Bustos BI, Bandres-Ciga S, et al. Genome-wide epistasis analysis in Parkinson’s disease between populations with different genetic ancestry reveals significant variant-variant interactions. medRxiv. 2022:2022.07. 29.22278162. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2011;88(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JL, Abecasis GR. GAS Power Calculator: web-based power calculator for genetic association studies. bioRxiv. 2017:164343. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boughton AP, Welch RP, Flickinger M, et al. LocusZoom.js: interactive and embeddable visualization of genetic association study results. Bioinformatics. 2021;37(18):3017–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwaki H, Leonard HL, Makarious MB, et al. Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Parkinson’s Disease. Genetic Resource. Mov Disord. 2021. Aug;36(8):1795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson AR, Smith EN, Matsui H, et al. Effective filtering strategies to improve data quality from population-based whole exome sequencing studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014. May 2;15:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38(16):e164–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic acids research. 2019;47(D1):D886–D94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Emond MJ, Bamshad MJ, et al. Optimal unified approach for rare-variant association testing with application to small-sample case-control whole-exome sequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2012. Aug 10;91(2):224–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Teslovich TM, Boehnke M, Lin X. General framework for meta-analysis of rare variants in sequencing association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2013. Jul 11;93(1):42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaivola K, Shah Z, Chia R, Scholz SW. Genetic evaluation of dementia with Lewy bodies implicates distinct disease subgroups. Brain. 2022;145(5):1757–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piras IS, Bleul C, Schrauwen I, et al. Transcriptional profiling of multiple system atrophy cerebellar tissue highlights differences between the parkinsonian and cerebellar sub-types of the disease. Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 2020;8:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JY, Lee EK, Park SS, et al. Association of DRD3 and GRIN2B with impulse control and related behaviors in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2009. Sep 15;24(12):1803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winder-Rhodes SE, Hampshire A, Rowe JB, et al. Association between MAPT haplotype and memory function in patients with Parkinson’s disease and healthy aging individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2015. Mar;36(3):1519–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sampedro F, Marín-Lahoz J, Martínez-Horta S, Pagonabarraga J, Kulisevsky J. Early Gray Matter Volume Loss in MAPT H1H1 de Novo PD Patients: A Possible Association With Cognitive Decline. Front Neurol. 2018;9:394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setó-Salvia N, Clarimón J, Pagonabarraga J, et al. Dementia Risk in Parkinson Disease: Disentangling the Role of MAPT Haplotypes. Archives of Neurology. 2011;68(3):359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merello E, Mascelli S, Raso A, et al. Expanding the mutational spectrum associated to neural tube defects: Literature revision and description of novel VANGL1 mutations. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2015;103(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iliescu A, Gravel M, Horth C, Kibar Z, Gros P. Loss of membrane targeting of Vangl proteins causes neural tube defects. Biochemistry. 2011. Feb 8;50(5):795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mentink RA, Rella L, Radaszkiewicz TW, et al. The planar cell polarity protein VANG-1/Vangl negatively regulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling through a Dvl dependent mechanism. PLoS Genet. 2018. Dec;14(12):e1007840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berwick DC, Harvey K. The importance of Wnt signalling for neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012. Oct;40(5):1123–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stephano F, Nolte S, Hoffmann J, et al. Impaired Wnt signaling in dopamine containing neurons is associated with pathogenesis in a rotenone triggered Drosophila Parkinson’s disease model. Scientific Reports. 2018 2018/February/05;8(1):2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong X, Liao Z, Gritsch D, et al. Enhancers active in dopamine neurons are a primary link between genetic variation and neuropsychiatric disease. Nature Neuroscience. 2018 2018/October/01;21(10):1482–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soutar MPM, Melandri D, O’Callaghan B, et al. Regulation of mitophagy by the NSL complex underlies genetic risk for Parkinson’s disease at 16q11.2 and MAPT H1 loci. Brain. 2022. Dec 19;145(12):4349–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot for MAPT stratified GWAS. A. Q-Q plot of MAPT H1/H1 haplotype carriers B. Q-Q plot of MAPT H2 haplotype carriers.

Supplementary Table 1. Demography of studied population. Supplementary Table 2. Effect of novel SNPs EMP1 (rs56312722) and VANGL1 (rs11590278) variants on Parkinson’s disease age-at-onset in MAPT stratified cohorts. Supplementary Table 3. Burden analysis of rare EMP1 and VANGL1 variants in MAPT stratified cohorts. Supplementary Table 4. EMP1 variants with high CADD score.

Data Availability Statement

Full code used in the analysis has been made available on git-hub (https://github.com/gan-orlab/PD_stratified_GWAS).