Abstract

Background:

Project Step Up proposed to reduce alcohol consumption and alcohol-related negative outcomes in adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD).

Methods:

The 54 participants (30 females, 24 males) were assigned to either Project Step Up Intervention (SUI) or Control conditions and were assessed prior to intervention, immediately following intervention, and at 3-month follow-up. Adolescents in the SUI condition participated in a 6-week, 60-minute group intervention that provided alcohol education and promoted adaptive responses to alcohol-related social pressures. Caregivers attended concurrent but separate sessions on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on the brain and how to handle parenting challenges associated with alcohol use in teens with FASD.

Results:

Thirty-three percent (n = 18) of adolescents were classified as light/moderate drinkers, and 67% (n = 36) were abstinent/infrequent drinkers based on their lifetime drinking histories. Results revealed a significant decrease in self-reported alcohol risk and in alcohol-related negative behaviors (Cohen’s d = 1.08 and 0.99) in light/moderate drinkers in the SUI compared to the Control group. These results were partially sustained at 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, adolescents in the abstinent/infrequent group exhibited no increase in alcohol-related outcomes suggesting that the group intervention used in this study was not iatrogenic.

Conclusions:

The success of this treatment development study provides preliminary support for effective treatment of adolescents with FASD to prevent or reduce alcohol use and its negative consequences in this high risk population.

Keywords: Alcohol Misuse, Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, Alcohol Intervention, Adolescents

OVER THE PAST 40 years, mounting evidence has prompted increased attention to the role of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) in the occurrence of a wide range of disorders known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD; Warren et al., 2011). Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), one of the most severe conditions resulting from in utero alcohol exposure, is defined by a pattern of characteristic facial malformations, growth deficiencies, and neurodevelopmental deficits (Jones and Smith, 1973). A substantial body of research has documented significant neurocognitive difficulties among individuals with FAS as well as among individuals who have been prenatally exposed to alcohol but do not meet full criteria for FAS (Chasnoff et al., 2010; Doyle and Mattson, 2015; Guerri et al., 2009; Kable et al., 2016; Kodituwakku, 2009; Quattlebaum and O’Connor, 2013). This latter group of individuals is described as having partial FAS (pFAS), or alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), according to the diagnostic categories proposed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (Hoyme et al., 2005; Stratton et al., 1996). The entire continuum of effects is estimated to represent up to 5% of the population of children born in the United States (May et al., 2014), up to 2.5% of whom have FAS or pFAS (May et al., 2015), suggesting that the effects of PAE are pervasive and represent a major public health concern. Recently, the cognitive and behavioral deficits seen in individuals with PAE have been further refined by Kable and colleagues (2016) in the DSM 5 as Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated with PAE.

Individuals with PAE have multiple developmental deficits in cognition, self-regulation, and adaptive function (Astley, 2010; Chasnoff et al., 2010; Doyle and Mattson, 2015; Kable et al., 2016; Kodituwakku, 2009; Mattson et al., 2013; Quattlebaum and O’Connor, 2013). Given the neurocognitive problems associated with PAE, it is not surprising that psychosocial dysfunction has been consistently noted in the literature. Longitudinal studies suggest that individuals with PAE are at a greatly increased risk for adverse long-term outcomes, including psychiatric disorders and poor social adjustment (O’Connor, 2014; O’Connor and Paley, 2009; Streissguth et al., 2004). In particular, as they mature, individuals with PAE exhibit problems with the misuse of alcohol, with estimates of prevalence rates ranging from 35 to 60% (Famy et al., 1998; Streissguth et al., 2004). Two well-designed prospective developmental studies shed light on these findings (Alati et al., 2006, 2008; Baer et al., 1998, 2003). These studies found an increase in alcohol misuse among 14-year-old prenatally exposed adolescents which was subsequently related to alcohol use disorders in adulthood.

Such findings indicating increased vulnerability to alcohol use disorders in adolescent and adult humans with PAE have been replicated in animal models (Spears and Molina, 2005; Uban et al., 2013). For example, under ad libitum conditions, rodent models of PAE show enhanced preference for alcohol and increased alcohol consumption particularly during adolescence (Chotro et al., 2007). Some mechanisms have been proposed for this association and include those that are related to the teratological effects of the alcohol on the neurochemical systems involved in the reinforcing effects of abuse drugs, as well as on the regulatory systems of the stress response resulting in long-lasting alterations in both the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) and dopaminergic (DA) systems. Both HPA and DA systems are important for resilience against addiction which appears to be disrupted by PAE (Sinha, 2009).

Given the significant negative outcomes associated with alcohol abuse, particularly in individuals with PAE, youth with FASD who have not yet begun to use or who are currently using alcohol are a compelling target for early alcohol intervention. Unhealthy habits affecting both physical and mental well-being in adulthood begin during adolescence. Thus, intervention during this time may have both short- and long-term benefits. Unfortunately, programs focusing on teaching adolescents about the effects and consequences of alcohol use with abstinence as the main objective have generally been unsuccessful in the reduction of use among teens, with some interventions resulting in unintended iatrogenic effects (Brown et al., 2005; Werch and Owen, 2002). It is speculated that the reason for this failure is that these programs fail to address salient concerns of youth that may motivate their drinking behavior and may actively prompt resistance to the intervention. Developmentally, the normal trajectory for adolescents is to experiment with the use of alcohol which makes it difficult for them to identify when their alcohol use is leading to negative long-term consequences. For this reason, intervention efforts need to increase a perceived need for change using approaches that normalize change efforts, provide education, and promote harm reduction.

A harm reduction approach is one that aims to provide practical knowledge and skills to enable young people to make safer decisions in regard to alcohol use and should be evaluated in terms of reduction in risk and harm. The great advantage of a harm reduction approach is that it provides for flexibility, allowing the intervention content to meet youth at their individual level of experience and knowledge in relation to alcohol issues (Marlatt and Witkiewitz, 2010). At the same time, research indicates that teaching harm reduction strategies does not increase use among individuals who are nonusers (Hamilton et al., 2007). To this end, Project Step Up incorporated motivational enhancement techniques, normative feedback, education, risk assessment, coping and alcohol refusal skills training in working with adolescents within a developmentally sensitive group framework in order to target adolescents experiencing common developmental transitions with varying levels of alcohol use from no use to light/moderate use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Objectives and Design

Our objective was to pilot the methods of Project Step Up to prevent/reduce alcohol-related negative outcomes in adolescents with FASD. A second objective was to determine whether or not there would be an increase in alcohol risk in abstinent youths as a function of participating in the intervention.

Recruitment, data collection, and treatment were conducted in a university setting in the United States. Adolescents were assigned in alternating sequence, based on when they were enrolled, to 1 of 2 study conditions, Step Up Intervention (SUI) or Control. Attempts were made to equate groups on gender and age. Adolescents in the SUI condition were treated in groups averaging approximately 6 to 8 participants. The intervention consisted of 6, 60-minute sessions delivered over the course of 6 weeks. Caregivers and adolescents attended separate but concurrent sessions. Two therapists (male, female) led each adolescent group, and 2 therapists led each parent group. Adolescents and caregivers in the Control condition were provided with written materials on alcohol misuse and stress reduction. Self-report outcome measures were completed by participants prior to intervention, immediately following intervention, and at 3-month follow-up.

Participants

Recruitment methods consisted of community-posted flyers, contact with local healthcare providers, YMCAs, school administrators, community mental health centers, and caregiver groups. To meet eligibility criteria, participants had to: (i) be between 13 and 18 years of age; (ii) have a Composite IQ of ≥70; (iii) be English speaking; (iv) be living with at least 1 custodial parent or guardian; and (v) have a history of PAE. Adolescents were not enrolled if they had a past diagnosis of intellectual disability, psychotic disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder.

Interested families contacted the project coordinator, who conducted a screening interview by telephone to determine initial eligibility. Recruitment efforts yielded a total of 83 participants who agreed to be screened for eligibility. Following screening, 56 adolescents met eligibility requirements and participated in the study. Failure to meet these requirements was due to: (i) no reliable documentation of PAE (n = 8); (ii) a previous diagnosis of intellectual disability (n = 1) or pervasive developmental disorder (n = 1); (iii) did not meet age requirements (n = 7); or (iv) failure to keep eligibility appointment (n = 10). Two participants assigned to the SUI condition dropped out of the study because of conflicting obligations. Of the eligible remaining 54 participants, 55.6% were female, averaging 15.69 (SD = 1.74) years of age. Approximately 55.6% of the sample identified themselves as White, Non-Hispanic, 7.4% as Black Non-Hispanic, 33.3% as Hispanic, and 3.8% as Native American or Asian. The participants’ average IQ was 91.11 (SD = 12.99). Approximately 68.5% of sample caregivers were married or living with a partner, and average educational level of the primary caregiver was 16.37 (SD = 3.36) years. In all, 73% of participants were adopted, 21.2% were in foster or family guardian care, and 5.8% were living with their biological mother/father (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics Including Total Sample, Abstinent/Infrequent Lifetime Alcohol Users, and Light/Moderate Lifetime Alcohol Users Comparing Step Up Intervention (SUI) to Control Groups

| Variables | Total sample (N = 54) | Abstinent/infrequent SUI (n = 15) | Abstinent/infrequent Control (n = 21) | Light/moderate SUI (n = 11) | Light/moderate Control (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender—females (%) | 55.6 | 53.3 | 57.1 | 63.6 | 57.1 |

| Age in years (M, SD) | 15.69 (1.74) | 15.44 (1.60) | 14.79 (1.42) | 16.68 (1.37) | 17.38 (1.61) |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 55.6 | 60.0 | 57.1 | 45.5 | 57.1 |

| Composite IQ (M, SD) | 91.11 (12.99) | 93.53 (11.27) | 93.19 (14.51) | 89.27 (12.75) | 82.57 (10.05) |

| Primary caregiver married/partner (%) | 68.5 | 66.7 | 57.3 | 81.8 | 85.0 |

| Primary caregiver years of education (M, SD) | 16.37 (3.36) | 15.87 (3.00) | 17.33 (3.75) | 15.45 (3.08) | 16.00 (3.27) |

| Caregiver relation to adolescent (%) | |||||

| Adopted/foster/legal guardian | 94.2 | 90.1 | 95.2 | 90.9 | 100.0 |

| Biological mother/father | 5.8 | 8.9 | 4.8 | 9.1 | 0.00 |

| FASD classification (%) | |||||

| FAS/pFAS | 85.2 | 80.0 | 90.5 | 90.9 | 85.7 |

| ARND | 14.8 | 20.0 | 9.5 | 9.1 | 14.3 |

ARND, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; FAS, fetal alcohol syndrome; FASD, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders; pFAS, partial FAS.

Procedure

Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent.

The University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all procedures. A certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). University IRB-approved forms were used to obtain consent from caregivers and from adolescents 18 years of age and assent from adolescents 13 to 17 years of age.

Description of Treatment and Control Conditions.

Project Step Up Intervention—

Adolescent Group—

The intervention procedure used in this study and all its components have been validated empirically and have been successfully implemented with typically developing high school youth (Project Options; Brown et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the procedure was modified with specific treatment adaptations to account for the neurocognitive deficits common among adolescents with FASD (see Laugeson et al., 2007). The content and procedures for modifications that were made primarily involved augmentation in how the intervention was delivered, rather than changes in the content or components of the intervention. The intervention strategies that work best with individuals with FASD modeling, coaching, behavioral rehearsal, and performance feedback were used extensively in the modification of the protocol.

A Project Step Up Treatment Manual for Teens was developed for therapists along with a separate Project Step Up Teen Workbook for participants in order to help them understand and remember important intervention concepts more easily. These materials were reviewed by nonparticipant adolescents with FASD, and their parents and suggestions were incorporated into the final version of the intervention manual and workbook (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adolescent and Caregiver Intervention Session Content

| Session | Adolescent session content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Normative feedback regarding peer alcohol use, standard drink size, amount of alcohol in common beverages, discussion of how youth cease or reduce alcohol use |

| 2 | Alcohol beliefs/expectations, alcohol expectancy challenge |

| 3 | How to deal with stress, adaptive coping without using alcohol |

| 4 | Types of drinkers, negative consequences of drinking, resisting peer pressure, alternative activities |

| 5 | Resistance and refusal skills, how to handle situations where alcohol is present |

| 6 | Communication skills to avoid risky/negative situations or problems with others |

| Session | Caregiver session content |

| 1 | Prenatal alcohol exposure and neurocognitive development, FASD criteria, reframing teen behaviors |

| 2 | Alcohol and teens with FASD, protective factors, signs of misuse |

| 3 | Importance of structure, benefits of strong parent-teen relationship, supervision, and communication |

| 4 | Monitoring teens, handling common conflict scenarios, drinking in the home |

| 5 | How to talk to your teen about alcohol, facts, and myths about alcohol |

| 6 | Action steps, parent self-care, additional resources for parents of teens with FASD |

FASD, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

Caregiver Group—

An important component of the parent intervention was to empower caregivers in assisting their teens to resist alcohol use. Sessions included an opportunity for caregivers to describe their own thoughts, feelings, and fears related to their adolescents’ behaviors and strategies for facilitating change. The content of the caregiver sessions was adapted from the NIAAA protocol entitled, Make a Difference: Talk to Your Child About Alcohol (NIAAA, 2006, http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/MakeADiff). Although this protocol was developed primarily for younger teens, its content is appropriate for the caregivers of teens with FASD who require more parental oversight and supervision (Table 2).

Control Condition—

Adolescents and caregivers in the Control condition completed the pre-, postintervention, and follow-up assessment battery in parallel fashion to those in the active intervention condition. They were given written materials on alcohol misuse and stress reduction techniques to take home to read following the pre-intervention assessment.

Group Leader Training.

The first task of training was to educate the group leaders about the challenges faced by individuals with FASD. To this end, group leaders were provided lectures and group activities to increase knowledge, change attitudes, and build skills in working with individuals with FASD. Didactic information was provided on the primary and secondary disabilities in individuals with FASD and on intervention strategies that are effective with these individuals. Training was provided regarding common group dynamics, how to actively engage adolescents in the groups, and how to interact with them in a nonjudgmental and supportive manner so as to facilitate participation and receptivity to intervention. As part of their training and prior to beginning the intervention, all group leaders underwent training in the identification and risk assessment of alcohol abuse and/or dependence using the criteria established by the NIAAA. All group leaders were provided with the Project Step Up Treatment Manual that included information on the objectives of training, curriculum content, goals of each session, a step-by-step explanation of how to conduct each session, and information on participant confidentiality.

Group leaders observed supervising staff conduct groups and practiced the protocol under situations closely representing actual study procedures. Supervisors rated group leader performance using fidelity checklists keyed to the intervention manuals. Group leaders obtained an overall fidelity rating ≥95% before leading an actual group.

Supervision and Assurance of Treatment Fidelity.

Group leaders met in person with the study principal investigator on a weekly basis for supervision to discuss issues that arose during the intervention sessions. Fidelity checklists covering all session objectives, as outlined in the intervention manuals, were created for each session. Undergraduate student volunteers were trained to code for treatment fidelity and provided immediate feedback during each session if group leaders failed to cover all aspects of a session (O’Connor et al., 2006, 2012). Thus, the integrity of the intervention was assured through the use of trained and qualified group leaders, standardized manuals, ongoing weekly supervision, and live monitoring of sessions (Moncher and Prinz, 1991).

Measures

Eligibility Measures.

FASD Diagnosis—

Every adolescent received a physical examination by a clinical geneticist to assess for the presence of the diagnostic features of FASD using the Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Astley, 2004). This system uses a 4-digit diagnostic code reflecting the magnitude of expression of 4 key diagnostic features of FAS: (i) growth deficiency; (ii) the FAS facial phenotype, including short palpebral fissures, flat philtrum, and flat upper vermillion border; (iii) central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction; and (iv) gestational alcohol exposure. Using this code, the magnitude of expression of each feature was ranked independently on a 4-point scale with 1 reflecting complete absence of the feature and 4 reflecting the full manifestation of the feature. The study geneticist administered this examination following reliability training with the senior study clinician (k = 100%).

After the 4-digit code for each participant was calculated, participant diagnosis was converted to the modified IOM criteria according to the guidelines developed by Hoyme and colleagues (2005). Using the Hoyme system, only 2 of 3 facial features must be present to meet the face criterion for FAS/pFAS and palpebral fissure lengths need only be ≤10th percentile. As it is not specified in the Hoyme system, we defined the CNS criterion as scoring 1½ standard deviations below the mean on 3 or more standardized assessments conducted by our team neuropsychologist. Using this classification scheme, 16.7% of adolescents were diagnosed with FAS, 68.5% with pFAS, and 14.8% with ARND (Table 1). The large number of individuals with pFAS diagnoses was due to the fact that they met face but not growth criteria.

Demographic Questionnaire—

All caregivers completed a demographic questionnaire that included the adolescent’s gender, age, ethnicity, caregiver marital status, caregiver years of education, and caregiver relation to the adolescent.

Lifetime Alcohol Use—

Participants were interviewed regarding their lifetime experience with alcohol. Those with 0 or 1 lifetime drinking episodes were classified as abstinent or infrequent users. Those with 2 or more lifetime drinking episodes were classified as light to moderate users.

Health Interview for Women—

Biological parents were interviewed using the Health Interview for Women (O’Connor et al., 2002), which yields standard measures of the average number of drinks per drinking occasion and the frequencies of those occasions. One standard drink was considered 0.60 oz of absolute alcohol (e.g., one 12-oz can of beer containing 5% absolute alcohol was considered 1 standard drink). The use of other drugs during gestation was also codified.

Questionnaire for Foster/Adoptive Parents—

For adopted or foster children, medical or legal records documenting known exposure or reliable collateral reports by others who had observed the mother drinking during pregnancy were obtained. Such documentation included medical records that indicated the biological mother was intoxicated at delivery or records indicating that the mother was observed drinking alcohol during pregnancy by a reliable collateral source (i.e., friend, close relative, partner, or spouse). These records provided sufficient information to meet the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Astley, 2004). Because many children with PAE are in foster care or are adopted, it is often necessary to employ review of such records as an accepted method by the scientific community for establishing PAE (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004).

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test—Second Edition—

The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test—Second Edition (K-BIT-2; Kaufman and Kaufman, 2004) is a brief instrument used to assess intellectual functioning along verbal (Verbal subtest) and nonverbal (Nonverbal subtest) domains. The K-BIT-2 IQ Composite score is an estimate of general intellectual functioning and is presented as a standard score with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The test has demonstrated high internal consistency across ages 4 through 18 for the Verbal (M = 0.90) and Nonverbal subtests (M = 0.88), as well as the IQ Composite (M = 0.93). Test–retest reliability is 0.88 for Verbal, 0.76 for Nonverbal, and 0.88 for the IQ Composite scores. The correlation between the IQ Composite score and the General Ability Index of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition is 0.84. Only the IQ Composite score was considered in this study.

Outcome Measures.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 2001) was developed by the World Health Organization as a simple method of screening for excessive drinking and to assist in brief assessment. It provides a framework for intervention to help hazardous and harmful drinkers reduce or cease alcohol consumption and thereby avoid the harmful consequences of their drinking. The AUDIT contains 10 items measuring alcohol consumption and complications of drinking and has typically identified high risk drinking in adults with a cutoff score of 8 or above. However, it has been shown to have high sensitivity (0.88) and specificity (0.81), at a score of 2 or above, for identifying alcohol problem use in a validation trial of 14- to 18-year-old patients arriving for routine health care at a large, hospital-based adolescent clinic (Knight et al., 2001, 2003). The AUDIT is recommended for use when clinicians wish to identify possible adolescents for brief alcohol intervention (Knight et al., 2003).

Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index—

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989) is a 23-item self-administered screening tool for assessing adolescent problem drinking. It has been used in research to indicate the frequency of experiencing negative consequences due to alcohol use. In particular, it measures the impact of alcohol on social and health functioning and has been used as a measure reflecting harm reduction following intervention. It has demonstrated high reliability and validity, and accurately discriminates between clinical and nonclinical samples (White and Labouvie, 1989). Items include negative consequences of alcohol misuse like passing out, having problems in school, getting into fights, having withdrawal symptoms, and being told by others a need to cut down on alcohol use.

CRAFFT—

The CRAFFT (Knight et al., 2001) is a 6-item measure that was designed for use specifically with adolescents. The name CRAFFT is a mnemonic acronym for significant key words in the test’s 6 questions: (C) Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who was high or had been using alcohol or drugs? (R) Do you ever use alcohol or drugs to RELAX, feel better about yourself, or fit in? (A) Do you ever use alcohol or drugs while you are by yourself, ALONE? (F) Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol or drugs? (F) Do your family or FRIENDS ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking or drug use? (T) Have you ever gotten into TROUBLE while you were using alcohol or drugs? The CRAFFT has excellent sensitivity (0.92) and adequate specificity (0.64) at a score of 1 for alcohol problem use in typically developing adolescents between the ages of 14 and 18 years (Knight et al., 2003).

Satisfaction Measures.

Participant satisfaction questionnaires, 1 for adolescents and 1 for caregivers, were developed for this research. All items were scored on a 3-point scale, with a score of 3 reflecting satisfaction, a score of 2 reflecting a neutral opinion or no change, and a score of 1 reflecting dissatisfaction. Questions probed the degree of applicability, palatability, and acceptability of the intervention. Furthermore, we asked respondents whether or not they felt the intervention helped them and how confident they were in their ability to manage future situations in which alcohol was involved based upon what they learned.

Data Analysis Plan

Data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 21.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Analyses were conducted on scores derived from the AUDIT, RAPI, and CRAFFT. Adolescent gender, age, ethnicity, Composite IQ, and FASD classification were evaluated in preliminary analyses to determine possible covariate status. Other possible covariates included caregiver marital status, years of education, and relationship to adolescent. The effectiveness of the intervention was evaluated in separate Treatment Condition (SUI, Control) analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs), using pre-intervention scores as primary covariates to correct for differences in initial levels. Postintervention and 3-month follow-up scores were outcome variables in these analyses. Variables were examined for outliers to address the possibility of non normal distributions and a transformation (square root of X + 1) was required. As an example, a score of 5 on the RAPI transforms to a score of 2.45. Effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988).

RESULTS

Alcohol and Other Drug Use

The percentage of any current illicit drug use was 1.9% for amphetamines and cocaine with 13.5% of respondents acknowledging the use of marijuana. Thirty-three percent of participants reported light/moderate lifetime alcohol use, while the majority of the sample reported abstinence or infrequent use (67%). For this reason, the groups were evaluated separately.

Comparison of SUI to Control in Abstinent/Infrequent Drinkers

Chi-square and independent t-tests for the abstinent/infrequent drinkers revealed no statistically significant differences at pre-intervention between the SUI and Control conditions on study demographic variables or lifetime alcohol use and no relation to treatment outcomes (Table 1).

Results for the abstinent/infrequent use group revealed no differences or change in outcome measures postintervention or at 3-month follow-up as a function of intervention. For this group, mean scores in both SUI and Control conditions remained at 0.

Comparison of SUI to Control in Light/Moderate Drinkers

Chi-square and independent t-tests for the light/moderate drinkers revealed no statistically significant differences at pre-intervention between the SUI and Control conditions on study demographic variables or lifetime alcohol use and no relation to treatment outcomes (Table 1).

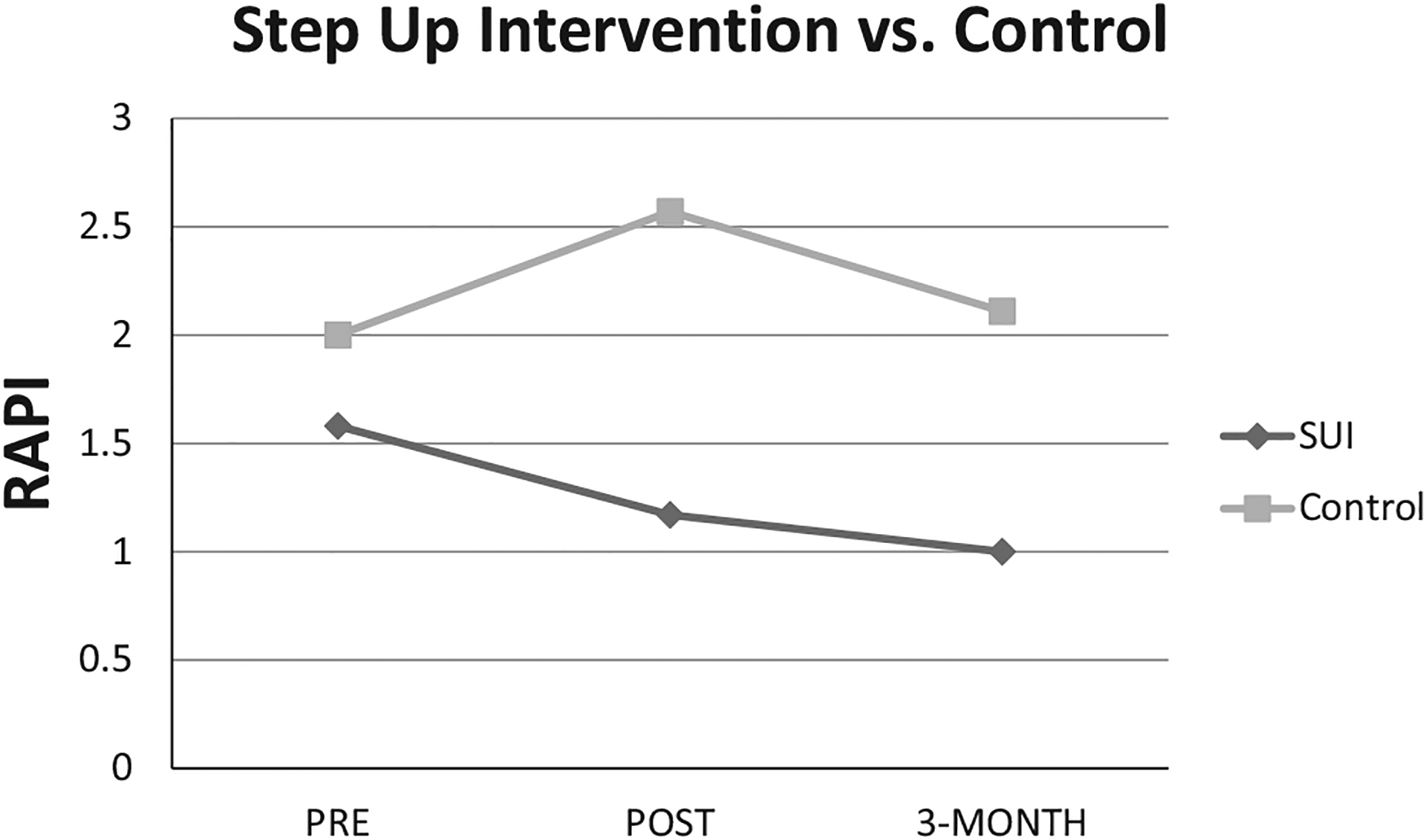

Table 3 presents the results of the comparison between the SUI and the Control conditions on alcohol-related outcome measures following intervention for the light/moderate alcohol group. Analyses yielded significant treatment effects, with the adolescents in the SUI group reporting significantly lower levels of alcohol risk and fewer negative behaviors following intervention than those in the Control group, AUDIT, F(1, 15) = 5.43, p = 0.03, and RAPI, F (1, 15) = 8.60, p = 0.01. Large treatment effects were demonstrated for both outcomes: Cohen’s d = 1.08 and 0.99, respectively. Due to the extremely low occurrence of the behaviors measured by the CRAFFT in this sample, no significant differences were found on this measure.

Table 3.

Intervention Outcomes for the Light/Moderate Lifetime Alcohol Use Group

| Variables | SUI M (SD) n = 11 |

Control M (SD) n = 7 |

SUI Adjusted M (SE) n = 11 |

Control Adjusted M (SE) n = 7 |

F | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUDIT | ||||||

| Postintervention | 1.35 (0.61) | 2.86 (1.86) | 1.64 (0.20) | 2.42 (0.26) | 2.33* | 1.08 (0.07, 1.49) |

| 3-Month follow-up | 1.56 (0.95) | 2.74 (1.98) | 1.86 (0.29) | 2.27 (0.37) | 0.75 | 0.76 (−0.60,1.43) |

| RAPI | ||||||

| Postintervention | 1.17 (0.44) | 2.57 (1.95) | 1.32 (0.21) | 2.32 (0.26) | 2.93** | 0.99 (0.27, 1.71) |

| 3-Month follow-up | 1.00 (0.00) | 2.11 (1.91) | 1.14 (0.22) | 1.89 (0.27) | 2.13* | 0.83 (0.001, 1.49) |

SUI, Step Up Intervention condition; C, Control condition; AUDIT, alcohol use disorders test; RAPI, Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index; CI, confidence interval.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Data were transformed using square root of X + 1. Effect size was calculated using the standardized difference in means based on the raw group means divided by the pooled standard deviation, Cohen’s d. By convention, d = 0.8 corresponds to a large effect size.

Statistically significant gains achieved immediately following intervention were sustained over the 3-month follow-up period for the RAPI, F(1, 15) = 4.53, p = 0.05, Cohen’s d = 0.83 (Fig. 1). Although not statistically significant, effect size for the AUDIT at follow-up was large with a Cohen’s d = 0.76.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of light/moderate lifetime drinkers in the Step Up Intervention (SUI) versus Control using transformed raw scores (square root of X + 1) pre-intervention, postintervention, and at 3-month follow-up on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI).

Adolescent and Caregiver Satisfaction

All families were queried on satisfaction with the treatment that they received in the SUI condition immediately following intervention. Ninety-six percent of adolescents reported that they were confident that they could avoid risky situations related to alcohol use based upon what they learned in their groups and 92.3% felt that the program was helpful to them. Ninety-six percent of caregivers stated that they believed that it would be easier for their adolescents to make better choices regarding alcohol because of the intervention and 96% reported that they were satisfied with the intervention.

DISCUSSION

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that a manualized treatment using a standardized harm reduction approach adapted for the neurocognitive deficits of teens with FASD and administered by therapists trained in treatment delivery resulted in a reduction in alcohol use and its negative consequences in adolescents with FASD who were more experienced in the use of alcohol. Importantly, the intervention did not foster increased alcohol use in adolescents with little lifetime use experience. Furthermore, this particular intervention was found to be acceptable to both adolescents and their caregivers and was reported to be helpful to them.

Results of this study are consistent with findings from Project Options (upon which the intervention was based), which demonstrated that this type of intervention would have the greatest impact on youth with more alcohol use experience and alcohol-related problems (Brown et al., 2005). Findings are also similar to those reported from a large study that sought to examine the differential impact of an adapted version of the School Health and Alcohol Harm Reduction Project (SHAHRP), a classroom-based alcohol harm reduction intervention, on participants with different alcohol use experiences prior to intervention (McKay et al., 2014). It was hypothesized that unsupervised drinkers who received intervention would be significantly more influenced than abstainers or supervised drinkers. Significant positive behavioral effects (in terms of amounts of alcohol consumed, frequency of drinking, and alcohol-related harms) were observed almost exclusively among the unsupervised higher risk drinkers.

A note on the usefulness of the CRAFFT in this population of adolescents with FASD is warranted. Although the CRAFFT has been validated as a useful tool with typically developing teens, it was less effective in estimating negative behaviors associated with alcohol misuse than the AUDIT and the RAPI in this sample of adolescents affected by PAE. This finding may be because individuals with this developmental disability are less likely to engage in activities measured by the CRAFFT such as driving a car. For this reason, caution should be used when considering the use of this instrument to measure risk in PAE-affected individuals who may show less social maturity and opportunity for some activities than typically developing teens.

The conclusions of this study should be considered in the context of some limitations. Of note is that some factors restrict our ability to generalize study findings to larger populations of adolescents with FASD. First, it was necessary to work only with teens with Composite IQs of 70 or above because the intervention required that participants understood the instructions provided during the didactic portions of the sessions. This necessarily limited the general-izability of the study to some adolescents with FASD. Nevertheless, research shows that the majority of individuals with FASD function in the borderline to normal intellectual range. A previous investigation estimated that 73% of individuals with FAS and 91% of individuals with pFAS or ARND have IQs of 70 or above (Sampson et al., 2000). Furthermore, studies have shown that individuals without intellectual disabilities are at a comparatively greater risk for maladaptive outcomes than those with intellectual disabilities making this group of adolescents an important target for intervention (Fast and Conry, 2004; Roebuck et al., 1999; Streissguth et al., 1996).

A second limitation to generalization is that the study sample was composed of caregivers who were actively seeking help for their adolescents and who were highly motivated to participate in treatment. Although this may represent a potential limitation with regard to generalization to other adolescents and their families, research shows that individuals who have the best treatment outcomes are those who come from stable supportive homes and whose parents are actively involved in their care (El Nokali et al., 2010; Streissguth et al., 2004). Given the requirement of caregiver involvement for the success of the present intervention, we would expect that it is those highly motivated families who would benefit most from this particular intervention.

Third, because there are no current empirically based treatments for alcohol misuse in adolescents with FASD, the Control condition did not consist of an active alternative treatment to SUI. Nevertheless, SUI represents a first step in assessing viable treatment approaches for individuals affected by PAE. It is important that future studies compare the impact of SUI with alternative interventions that may differ in treatment outcome and cost effectiveness so that effective treatments can be available in routine clinical practice.

Fourth, the number of individuals with light/moderate drinking in this sample was relatively small in comparison with the abstinent group making the conclusions of the study preliminary. Larger samples of individuals with strong histories of alcohol use are needed. Encouraging is the finding that individuals in this particular sample, the majority of whom were living in foster or adoptive homes, were less inclined to be misusing alcohol in their teens.

Fifth, using the combination of 2 FASD diagnostic systems with the final diagnoses conforming to the IOM criteria proposed by Hoyme and colleagues (2005) may have resulted in a higher percentage of adolescents receiving diagnoses of FAS/pFAS than would be achieved using the 4-digit code alone. This finding may be due to the more relaxed criteria for face and growth retardation found in the Hoyme and colleagues (2005) diagnostic formulation. It is also possible that as an individual with PAE matures into adolescence, clearer physical and neurocognitive manifestations of the disorder may facilitate a more definitive diagnosis (Coles et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the problem in convergent validity among various diagnostic systems remains a significant clinical issue needing further study.

In conclusion, study results indicate that adolescents with FASD who do not have global intellectual disabilities are able to benefit from interventions addressing alcohol misuse and its negative behavioral consequences. As the problems of individuals with FASD and their individual, financial, and social impacts are better understood, it becomes increasingly evident that there is a pressing need for specialized interventions for these individuals in order to reduce negative secondary problems. This is particularly true of higher functioning individuals with FASD who are less likely to be identified and treated than more severely affected individuals, and thus are at arguably greater risk for maladaptive outcomes. Our results also point to the need for caregivers to be actively involved in intervention programs designed for adolescents with FASD. By learning effective strategies for communication and supervision of their teens, caregivers can provide support for the developing efforts at individuation of their adolescents while still providing an appropriate protective environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The writing of this manuscript was supported by funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, grant number: # U84 DD000504 (M. O’Connor, PI). Special thanks to Dr. Sandra Brown who served as a consultant on this project. Assistance was also provided by Stephanie Cordel, Larissa Portnoff, Michael Lesback-Coleman, Shital Gaitonde, Mina Parks, Lauren Elder, Jennifer Gerdts, and Lindsay Sterling. The contents do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and endorsement by the Federal Government should not be assumed. The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Alati R, Al Mamun A, Williams GM, O’Callaghan M, Najman JM, Bor W (2006) In utero alcohol exposure and prediction of alcohol disorders in early adulthood: a birth cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63:1009–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alati R, Clavarino A, Najman JM, O’Callaghan M, Bor W, Mamun AA, Williams GM (2008) The developmental origin of adolescent alcohol use: findings from the Mater University Study of Pregnancy and its outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 98:136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ (2004) Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code-Third Edition. University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ (2010) Profile of the first 1,400 patients receiving diagnostic evaluations for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder at the Washington State Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Diagnostic & Prevention Network. Can J Clin Pharmacol 17:132–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Montiero MG (2001) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines of Use in Primary Care. 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Barr HM, Bookstein FL, Sampson PD, Streissguth AP (1998) Prenatal alcohol exposure and family history of alcoholism in the etiology of adolescent alcohol problems. J Stud Alcohol 59:533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Sampson PD, Barr HM, Connor PD, Streissguth AP (2003) A 21-year longitudinal analysis of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on young adult drinking. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60:377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Anderson KG, Schulte MT, Sintov ND, Frissell KC (2005) Facilitating youth self-change through school-based intervention. Addict Behav 30:1797–1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for Referral and Diagnosis. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/documents/fas_guidelines_accessible.pdf . Accessed December 20, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, Telford E, Schmidt C, Messer G (2010) Neurodevelopmental functioning in children with FAS, pFAS, and ARND. J Dev Behav Pediatr 31:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotro MG, Arias C, Laviola G (2007) Increased ethanol intake after prenatal ethanol exposure: studies with animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 31:181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Gailey AR, Mulle JG, Kable JA, Lynch ME, Jones KL (2016) A comparison among 5 methods for the clinical diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 40:1000–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle LR, Mattson SN (2015) Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE): review of evidence and guidelines for assessment. Curr Dev Disord Rep 2:175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Nokali NE, Bachman HJ, Votruba-Drzal E (2010) Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Dev 81:988–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS (1998) Mental illness in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects. Am J Psychiatry 155:552–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast DK, Conry J (2004) The challenge of fetal alcohol syndrome in the criminal legal system. Addict Biol 9:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerri C, Bazinet A, Riley EP (2009) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and alterations in brain and behavior. Alcohol Drug Res 44:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton G, Cross D, Resnicow K, Shaw T (2007) Does harm minimization lead to greater experimentation? Results from a school smoking intervention trial. Drug Alcohol Rev 26:605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme H, May P, Kalberg W, Kodituwakku P, Gossage J, Trujillo P, Robinson LK (2005) A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 Institute of Medicine criteria. Pediatrics 115:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW (1973) Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet 2:999–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JA, O’Connor MJ, Olson HC, Paley B, Mattson SN, Anderson SM, Riley EP (2016) Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure (ND-PAE): proposed DSM-5 diagnosis. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 47:335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL (2004) Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test—Second Edition (K-BIT-2). American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G (2001) Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among general adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:607–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G (2003) Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of the AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE, and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodituwakku PW (2009) Neurocognitive profile in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:218–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeson EA, Paley B, Schonfeld A, Frankel F, Carpenter EM, O’Connor MJ (2007) Social skills training for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: adaptations for manualized behavioral treatment. Child Fam Behav Ther 29:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Witkiewitz K (2010) Update on harm-reduction policy and intervention research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:591–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Roesch SC, Glass L, Deweese BN, Coles CD, Kable JA, May PA, Kalberg WO, Sowell ER, Adnams CM, Jones KL, Riley EP; CIFASD (2013) Further development of a neurobehavioral profile of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Baete A, Russo J, Elliott AJ, Blankenship J, Kalberg WO, Buckley D, Brooks M, Hasken J, Abdul-Rahman O, Adam MP, Robinson LK, Manning M, Hoyme HE (2014) Prevalence and characteristics of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 134:855–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Keaster C, Bozeman R, Goodover J, Blankenship J, Kalberg WO, Buckley D, Brooks M, Hasken J, Gossage JP, Robinson LK, Manning M, Hoyme HE (2015) Prevalence and characteristics of fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in a Rocky Mountain Region City. Drug Alcohol Depend 155:118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Sumnall H, McBride N, Harvey S (2014) The differential impact of a classroom-based, alcohol harm reduction intervention, on adolescents with different alcohol use experiences: a multi-level growth modelling analysis. J Adolesc 37:1057–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncher FJ, Prinz RJ (1991) Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. ClinPsychol Rev 11:247–266. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2006) Make a difference: talk to your child about alcohol. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/MakeADiff. Accessed December 15, 2008.

- O’Connor MJ (2014) Mental health outcomes associated with prenatal alcohol exposure: genetic and environmental factors. Curr Dev Disord Rep 1:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Frankel F, Paley B, Schonfeld AM, Carpenter E, Laugeson E, Marquardt RA (2006) A controlled social skills training for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 74:639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Kogan N, Findlay R (2002) Prenatal alcohol exposure and attachment behavior in children. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:1592–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Laugeson EA, Mogil C, Lowe E, Welch-Torres K, Keil V, Paley B (2012) Translation of an evidence-based social skills intervention for children with prenatal alcohol exposure in a community mental health setting. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36:141–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Paley B (2009) Psychiatric conditions associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quattlebaum JL, O’Connor MJ (2013) Higher functioning children with prenatal alcohol exposure: is there a specific neurocognitive profile? Child Neuropsychol 19:561–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck TM, Mattson SN, Riley EP (1999) Behavioral and psychosocial profiles of alcohol exposed children. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:1070–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM (2000) On categorizations in analyses of alcohol teratogenesis. Environ Health Perspect 108:421–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R (2009) Stress and addiction: a dynamic interplay of genes, environment, and drug intake. Biol Psychiatry 66:100–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears NE, Molina J (2005) Fetal or infantile exposure to ethanol promotes ethanol ingestion in adolescence and adulthood: a theoretical review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:909–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F (1996) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Kogan J, Bookstein FL (1996) Understanding the Occurrence of Secondary Disabilities in Clients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE): Final Report to the Center for Disease Control. Fetal Alcohol and Drug Unit, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O’Malley K, Young JK (2004) Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uban KA, Comeau WL, Ellis LA, Galea LAM, Weinberg J (2013) Basal regulation of HPA and dopamine systems is altered differentially in males and females by prenatal alcohol exposure and chronic variable stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38:1953–1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KR, Hewitt BG, Thomas JD (2011) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: research challenges and opportunities. Alcohol Res Health 34:4–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werch CE, Owen DM (2002) Iatrogenic effects of alcohol and drug prevention programs. J Stud Alcohol 63:581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW (1989) Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol 50:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]