Abstract

Background

: Mitigation measures, including school closures, were enacted to protect the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the negative effects of mitigation measures are not fully known. Adolescents are uniquely vulnerable to policy changes since many depend on schools for physical, mental, and/or nutritional support. This study explores the statistical relationships between school closures and adolescent firearm injuries (AFI) during the pandemic.

Methods

: Data were drawn from a collaborative registry of 4 trauma centers in Atlanta, GA (2 adult and 2 pediatric). Firearm injuries affecting adolescents aged 11–21 years from 1/1/2016 to 6/30/2021 were evaluated. Local economic and COVID data were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Georgia Department of Health. Linear models of AFI were created based on COVID cases, school closure, unemployment, and wage changes.

Results

: There were 1,330 AFI at Atlanta trauma centers during the study period, 1,130 of whom resided in the 10 metro counties. A significant spike in injuries was observed during Spring 2020. A season-adjusted time series of AFI was found to be non- stationary (p = 0.60). After adjustment for unemployment, seasonal variation, wage changes, county baseline injury rate, and county-level COVID incidence, each additional day of unplanned school closure in Atlanta was associated with 0.69 (95% CI 0.34- 1.04, p < 0.001) additional AFIs across the city.

Conclusion

: AFI increased during the COVID pandemic. This rise in violence is statistically attributable in part to school closures after adjustment for COVID cases, unemployment, and seasonal variation. These findings reinforce the need to consider the direct implications on public health and adolescent safety when implementing public policy.

Keywords: Adolescent firearm injuries, Violence, COVID-19, Injury prevention

Background

Firearm violence increased by 35% during the COVID-19 pandemic, compounding the already devastating loss of life from the virus [1]. Potential contributors to this spike in violence, which primarily occurred in the US [2], included increased availability of firearms [3], [4], [5], a rise in poverty [6], and unemployment [7]. The media has also suggested that decreasing trust in law enforcement or generalized feelings of social disorder may have contributed to the violence [8,9]. During this increase, firearms became the single greatest cause of mortality among children [10], with non-Hispanic black, urban adolescents being most at risk [11].

Many children in these vulnerable demographic groups depend on school for social, emotional, physical [12], and even nutritional security [13]. Furthermore, it has already been established that school closures during the early stages of COVID-19 disproportionately harmed the mental health of urban, minority youth [14,15]. It is plausible that loss of the support and physical safety provided schools contributed to the societal increases in youth violence, but this question has not been studied in detail.

This study evaluates relationships between school closures and adolescent firearm injuries (AFI) during the pandemic. This study uses a registry developed by Atlanta level 1 and 2 trauma centers capturing city-wide adolescent injuries. With adjustment for local economic, seasonal, and COVID-related variables, we investigate the independent statistical relationships between district-level school closures and the increase in AFIs.

Materials and methods

The current iteration of the Atlanta-based adolescent injury registry includes data from 4 trauma centers: a combined adult and pediatric Level 1 center, a Level 1 adult center that treats adolescents aged 15 and older, an independent Level 1 pediatric center, and a separate Level 2 pediatric center. The development of this study and the database were approved by Institutional Review Boards at each institution. The American Academy of Pediatrics definition of adolescents includes ages 11–21; this age range was used for inclusion. Firearm injuries were identified for dates 1/1/2020 to 6/30/2021. Injuries were connected to school district by patient county residence. Baseline county characteristics (total and adolescent population) were obtained from the Census Bureau [16]. County baseline AFI rates per 100,000 adolescents were calculated based on dates 1/1/16 to 2/28/20. Daily COVID-19 infection frequency was obtained from the Georgia Department of Health at the zip-code level [17] and standardized to the county population on weekly and monthly bases to calculate rates. Monthly, Atlanta metro unemployment rates and changes in wages were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics [18].

School closure data for 2016–2019 were obtained from calendars posted to district websites. Articles from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution were used to supplement district calendars and press releases to establish the dates of planned closure, unplanned closure, and remote-only education in 2020–21. Where counties had two public school districts (3 of 10 counties), closure data from the more populous district was used for analysis. Monthly school closure data was standardized to the baseline proportion of injuries per district to create an Atlanta-wide estimate of the percent of at-risk children whose schools were closed by month. On the district level, the monthly number of days schools had planned closures, unplanned closures, or remote-only were calculated. Lastly, on a per-district and weekly level, weeks were classified as having >2 days closed, <3 days closed, or fully open and by closure type (planned or unplanned). A comprehensive list of school closure data sources is available in Appendix 1. This study used Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines to optimize reporting [19].

Descriptive statistics were calculated for patient demographics, injury types, Injury severity scores, surgical interventions, mortality before discharge and length of stay. Time series were organized to visualize AFIs, COVID cases, school closure, seasonal variation, unemployment, and wage changes over time. Dickey-Fuller Testing to evaluate for stability of AFI over time. Mean changes from baseline COVID rates were calculated by school policy and COVID era.

Three linear models were created: Atlanta-wide, monthly; district level, monthly; and district level, weekly. All models of AFI included variables for school policy, COVID-19 infection rates, wage changes, unemployment, and seasonal variation. R2 contributions were estimated based on the Atlanta-wide, monthly data. The coefficient estimating the relationship between days closed/remote and AFIs at the monthly, district level was used to estimate the overall, adjusted increase in AFIs per day closed. A single sensitivity analysis was performed, with restriction of the population to age < 19.

Results

In total, 1330 adolescents were evaluated for firearm injuries at the trauma centers in Atlanta during the study period. 1130 resided in the 10 metro Atlanta counties (approximated adolescent population 782,465) and were included in the analysis. Patients were mostly non-Hispanic (94%, n = 1059), Black (89%, n = 1008) and male (87%, n = 984), and the mean age was 18.1 (Table 1 ). More than half of patients required surgical interventions in the OR (54%). The inpatient mortality rate was 13%, with 91% of deaths within the first 24 h of arrival.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| N | Percent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age | 11 to 14 | 112 | 9.90% |

| 15 to 18 | 454 | 40.20% | ||

| 19 to 21 | 564 | 49.90% | ||

| Sex | Female | 984 | 87.10% | |

| Male | 138 | 12.20% | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 0.70% | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic/Latino | 49 | 4.30% | |

| Non-Hispanic | 1065 | 94.20% | ||

| Unknown | 16 | 1.40% | ||

| Race | African American/Black | 1008 | 89.20% | |

| Asian | 5 | 0.40% | ||

| White | 50 | 4.40% | ||

| Other | 27 | 2.40% | ||

| Unknown | 40 | 3.50% | ||

| Injury Data | Descriptive (site and pre-hospital arrest) | Neck/Skull | 228 | 20.20% |

| Face | 154 | 13.60% | ||

| Thorax | 279 | 24.70% | ||

| Abdomen | 262 | 23.20% | ||

| Extremities | 532 | 47.10% | ||

| Superficial only | 108 | 9.60% | ||

| Pre-hospital arrest | 106 | 9.40% | ||

| Unavailable | 110 | 9.70% | ||

| ISS | 1 to 8 | 369 | 32.70% | |

| 9 to 15 | 386 | 34.20% | ||

| 16 to 24 | 165 | 14.60% | ||

| >24 | 210 | 18.60% | ||

| Outcomes | Surgical intervention | Yes | 608 | 53.80% |

| Unknown | 110 | 9.70% | ||

| Mortality before discharge | 145 | 12.80% | ||

| Length of inpatient stay (days) | 0 to 1 | 341 | 30.20% | |

| 2 to 4 | 301 | 26.60% | ||

| 4 to 7 | 136 | 12.00% | ||

| 8 to 14 | 139 | 12.30% | ||

| >14 | 213 | 18.80% | ||

| Length of stay if expired before discharge | 0 to 1 | 132 | 91.00% | |

| >1 | 13 | 9.00% | ||

On the time series, two spikes in AFI superimpose temporally over the initial spikes in COVID rates and the initial phase of school closure (Fig. 1 ). The mean AFI rates were higher than baseline for COVID era unplanned closures (123% over baseline, 95% confidence interval [CI] 66–181%) and COVID era remote teaching (73% over baseline, 95% CI 36–111%) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Time series. A: Injuries and COVID-19 Incidence. The monthly data is displayed according to the left Y axis, and the weekly data according to the right Y axis. B: Seasonal variation (by month) and school closure. Covariates. C: Economic covariates. Wage changes are standardized to a yearly rate and averaged over 3 months.

Fig. 2.

Unadjusted mean differences vs pre-COVID baseline rates under various conditions. This is based on weekly data and is standardized to district-level adolescent populations.

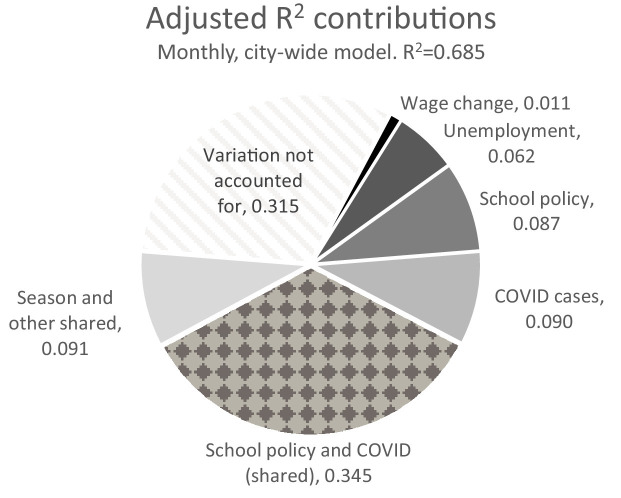

Relationships between school policy and AFI persisted in multivariable models after adjustment for COVID infections, county baseline injury, seasonal variation, and economic factors (Table 2 ). A significant difference was also observed between COVID era unplanned or remote school policies and COVID era planned breaks (difference in AFI/100k/year = 11.98, 95% CI 0.47–23.49, p = 0.0413). Therefore, based on the adolescent population in Atlanta, each additional day of unplanned school closure was associated with 0.69 (95% CI 0.34–1.04, p < 0.001) additional AFIs. The largest contributors to model fit were COVID infection rates and school policy, although there was considerable overlap between these two contributions (Fig. 3 ). A spike in AFIs in Spring of 2021 is not well-accounted for by the model (Fig. 4 ). The sensitivity analysis, which included only ages <19, did not reveal any change in result (Table 2).

Table 2.

Linear model coefficients: multivariable models of yearly AFIs/100k adolescents.

| Factors | Coefficient: | 95% Confidence Interval | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔAFI Rate per ΔFactor | |||||

| City-wide summary data, by month | |||||

| Percent of adolescents affected by school closure | 0.164/1% | 0.074 | 0.25 | 0.0006 | |

| City COVID rate | 0.344/1k | 0.159 | 0.53 | 0.0005 | |

| By county, by month | |||||

| Days closed for COVID | 1.06/day | 0.52 | 1.6 | <0.0001 | |

| Days remote for COVID | 0.99/day | 0.52 | 1.45 | <0.0001 | |

| Planned days closed | 0.23/day | -0.1 | 0.55 | 0.1719 | |

| County-level District infection rate | 0.561/1k | -0.06 | 1.18 | 0.0765 | |

| By county, by week | |||||

| Pre-COVID | Open | -13.15 (vs ref) | -23.25 | -3.1 | 0.0108 |

| Long weekend | -10.99 | -22.2 | 0.24 | 0.0552 | |

| Planned closure (>2 day) | -7.21 | -17.5 | 3.07 | 0.1677 | |

| COVID | Planned closure (>2 days) | 0 (reference) | – | – | |

| Open | -6.95 | -18.1 | 4.21 | 0.2226 | |

| Long weekend | -13.49 | -30 | 3 | 0.1093 | |

| Remote (>2 days) | 11.72 | -0.83 | 24.3 | 0.0673 | |

| Unplanned closure (>2 days) | 12.33 | -0.93 | 25.6 | 0.0685 | |

| Unplanned closure or remote | 11.98 | 0.47 | 23.5 | 0.0413 | |

| Sensitivity analysis: Only age <19 | |||||

| By county, by month | Days closed for COVID | 0.70/day | 0.19 | 1.21 | 0.0076 |

| Days remote for COVID | 1.04/day | 0.6 | 1.49 | <0.0001 | |

| By county, by week | Unplanned closure or remote | 14.81 | 3.55 | 26.1 | 0.0099 |

Fig. 3.

R2 contributions. This is based on Atlanta-wide, monthly data. The shared contribution of school policy and COVID cases is calculated by observing the difference in R2 after removing both from the model.

Fig. 4.

Model fit. This model is based on Atlanta-wide, monthly data.

Discussion

AFIs are associated with both unplanned school closures and remote-only teaching despite adjustment for COVID and societal factors. This finding lends credence to the idea that school is among the safest places for children to be based on rates of violent crime [20], and that children may depend on school for physical security [21]. Our study supports these findings with adolescent-specific, per-district and per-week precision, and estimates the magnitude of the increase in violence at 2 injuries per every 3 days closed.

Schools were closed during the first COVID waves for multiple, valid reasons. COVID-19 does pose a measurable threat to children; as of July 2022 in Georgia, 1720 children aged 10−17 have been hospitalized, and 21 have died due to the disease [17]. Another public health concern at the time was related to transmission to family members [22,23]. Additional infections pose threats to both the afflicted and the broader community in the context of limited hospital capacity by forcing operating rooms to shut down [24], [25], [26]. Many teachers also lost their lives to the complications of viral infection [27], although initial infections of teachers at school were generally from other staff members, rather than students [28].

However, the costs borne by children are significant and long-lasting. Children have suffered blows to mental health [29], academic achievement [30], and social development [31] during the pandemic. Our finding of additional violent injuries adds to this list of reasons to avoid closure or remote-only school in the future. Furthermore, multiple studies have found that schools appear to be able to control at-school transmission with implementation of appropriate preventative strategies [32]. In future pandemics, elected officials and government agencies will be responsible for weighing these priorities.

This study has numerous limitations. Above all, a great number of societal factors changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but we were only able to control for a small subset. Also, the assumed relationships between residence county and school district are likely to be affected by inconsistencies between district and county borders, as well as private schooling. Lastly, registry data is often affected by inaccuracies, and we did not validate the registry data (specifically, the mechanism of injury) with manual chart review. Further study is necessary to confirm our findings, such as through qualitative interviews at the patient level.

Conclusion

Firearm injuries increased in relation to unplanned school closures and remote schooling after adjustment for COVID incidence and socioeconomic factors. Increased risk of injury should be considered in addition to the other costs faced by adolescents when they lose access to resources provided by school.

Funding

This project is not funded by any grants.

Supplemental digital content

Appendix 1: Detailed references for closure dates and school calendars

CRediT authorship contribution statement

John N. Bliton: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Jonathan Paul: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Alexis D. Smith: Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Randall G. Duran: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Richard Sola: Writing – review & editing. Sofia Chaudhary: Writing – review & editing. Kiesha Fraser Doh: Writing – review & editing. Deepika Koganti: Writing – review & editing. Goeto Dantes: Writing – review & editing. Roberto C. Hernandez Irizarry: Writing – review & editing. Janice M. Bonsu: Writing – review & editing. Tommy T. Welch: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Roland A. Richard: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Randi N. Smith: Conceptualization, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.injury.2023.05.055.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kegler S.R., Simon T.R., Zwald M.L., Chen M.S., Mercy J.A., Jones C.M., et al. Vital signs: changes in firearm homicide and suicide rates - United States, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(19):656–663. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7119e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beiter K., Hayden E., Phillippi S., Conrad E., Hunt J. Violent trauma as an indirect impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of hospital reported trauma. Am J Surg. 2021;222(5):922–932. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hepburn L., Hemenway D. Firearm availability and homicide: a review of the literature. Aggr Violent Behav Rev J. 2004;9:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schleimer J.P., McCort C.D., Shev A.B., Pear V.A., Tomsich E., De Biasi A., et al. Firearm purchasing and firearm violence during the coronavirus pandemic in the United States: a cross-sectional study. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s40621-021-00339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laqueur H.S., Kagawa R.M.C., McCort C.D., Pallin R., Wintemute G. The impact of spikes in handgun acquisitions on firearm-related harms. Inj Epidemiol. 2019;6:35. doi: 10.1186/s40621-019-0212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poverty Henson T. Domestic Violence, and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Poverty Law Confer Sympos. 2020:16. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleimer J.P., Pear V.A., McCort C.D., Shev A.B., De Biasi A., Tomsich E., et al. Unemployment and crime in US cities during the Coronavirus pandemic. J Urban Health. 2022;99(1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s11524-021-00605-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaron Chalfin, MacDonald J. We don't know why violent crime is up. But we know there's more than one cause. Washington Post. 2021 7/9/2021.

- 9.Lopez G. Examining the Spike in Murders. New York Times, Morning Newsletter. 2022.

- 10.Goldstick J.E., Cunningham R.M., Carter P.M. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(20):1955–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2201761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christoffel K.K. Violent death and injury in US children and adolescents. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144(6):697–706. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150300095025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly M.R., Grigorian A., Swentek L., Arora J., Kuza C.M., Inaba K., et al. Firearm violence against children in the United States: trends in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2022;92(1):65–68. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000003347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLoughlin G.M., McCarthy J.A., McGuirt J.T., Singleton C.R., Dunn C.G., Gadhoke P. Addressing food insecurity through a health equity lens: a case study of large urban school districts during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urban Health. 2020;97(6):759–775. doi: 10.1007/s11524-020-00476-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banks A. Black Adolescent Experiences with COVID-19 and mental health services utilization. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(4):1097–1105. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01049-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawrilenko M., Kroshus E., Tandon P., Christakis D. The association between school closures and child mental health during COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey Microdata, 2020. Accessed 2/15/2022. Available from: https://data.census.gov/mdat/#/search?ds=ACSPUMS5Y2020.

- 17.Gerogia Department of Health. COVID-19 Status Report 2022. Accessed 2/15/2022. Available from: https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-status-report.

- 18.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Tables for Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA. Accessed 2/15/2022. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.ga_atlanta_msa.htm.

- 19.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., Initiative STROBE. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 16;147(8):573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):168. PMID: 17938396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Academies of Sciences; Division of behavioral and social sciences and education; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Committee on Summertime Experiences and Child and Adolescent Education, Health, and Safety; Hutton R, Sepúlveda MJ, editors. Shaping Summertime Experiences: Opportunities to Promote Healthy Development and Well-Being for Children and Youth. Washington DC: National Academies Press 2019. [PubMed]

- 21.Tomayko E.J., Thompson P.N., Smith M.C., Gunter K.B., Schuna J.M., Jr. Impact of reduced school exposure on adolescent health behaviors and food security: evidence from 4-day school weeks. J Sch Health. 2021;91(12):1055–1063. doi: 10.1111/josh.13095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aizawa Y., Shobugawa Y., Tomiyama N., Nakayama H., Takahashi M., Yanagiya J., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 cluster originating in a primary school teachers' room in Japan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(11) doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003292. e418-e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rae M., Neuman T., Kates J., Michaud J., Artiga S., Gary Claxton G.A., et al. Millions of Seniors Live In Households with School-Age Children: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2020. Accessed 2/15/2022. Available from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/millions-of-seniors-live-in-households-with-school-age-children/.

- 24.Siegler J.E., Zha A.M., Czap A.L., Ortega-Gutierrez S., Farooqui M., Liebeskind D.S., et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on treatment times for acute ischemic stroke: the society of vascular and interventional neurology multicenter collaboration. Stroke. 2021;52(1):40–47. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwok C.S., Gale C.P., Kinnaird T., Curzen N., Ludman P., Kontopantelis E., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2020;106(23):1805–1811. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen T.C., Thourani V.H., Nissen A.P., Habib R.H., Dearani J.A., Ropski A., et al. The effect of COVID-19 on adult cardiac surgery in the United States in 717 103 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(3):738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yea-Hung Chen P., MS, Ruijia Chen S., Charpignon M.-.L., Mathew V. Kiang S., Alicia R Riley P., MPH, M. Maria Glymour S., MS, et al. COVID-19 mortality among working-age Americans in 46 states, by industry and occupation: medRxiv; 2020 [Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/medrxiv/early/2022/04/18/2022.03.29.22273085.full.pdf.

- 28.Ismail S.A., Saliba V., Lopez Bernal J., Ramsay M.E., Ladhani S.N. SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in educational settings: a prospective, cross-sectional analysis of infection clusters and outbreaks in England. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):344–353. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Figueiredo C.S., Sandre P.C., Portugal L.C.L., Mazala-de-Oliveira T., da Silva Chagas L., Raony I., et al. COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents' mental health: biological, environmental, and social factors. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;106 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammerstein S., Konig C., Dreisorner T., Frey A. Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement-a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun J., Singletary B., Jiang H., Justice L.M., Lin T.J., Purtell K.M. Child behavior problems during COVID-19: associations with parent distress and child social-emotional skills. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2022;78 doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Centers for Disease Control. Science Brief: transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in K-12 Schools and Early Care and Education Programs – Updated: Centers for Disease Control, 2022. Accessed 2/15/2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/transmission_k_12_schools.html. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.