Abstract

It is known that post-retrieval extinction but not extinction alone could erase fear memory. However, whether the coding pattern of original fear engrams is remodeled or inhibited remains largely unclear. We found increased reactivation of engram cells in the prelimbic cortex and basolateral amygdala during memory updating. Moreover, conditioned stimulus– and unconditioned stimulus–initiated memory updating depends on the engram cell reactivation in the prelimbic cortex and basolateral amygdala, respectively. Last, we found that memory updating causes increased overlapping between fear and extinction cells, and the original fear engram encoding was altered during memory updating. Our data provide the first evidence to show the overlapping ensembles between fear and extinction cells and the functional reorganization of original engrams underlying conditioned stimulus– and unconditioned stimulus–initiated memory updating.

Functional reorganization of original fear engrams occurred in memory updating.

INTRODUCTION

Pathological memory is harmful but difficult to treat. Clinically, exposure therapy is commonly used to treat such cases, which is a process of fear extinction by repeatedly presenting the conditioned stimulus (CS) in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus (US) (1). However, it is not always effective as fear memory still exists with the phenomenon such as spontaneous recovery (SR) (2), which indicates that extinction normally leaves the original memory intact. It is reported that fear memory could be erased without SR by extinction training at the reconsolidation window (10 min to 6 hour) induced by either CS retrieval or US retrieval, which suggests that post-retrieval extinction treatment could induce fear memory updating (3, 4). In particular, specific CS retrieval before extinction (CS + Ext) could selectively erase the reactivated CS rather than other cue-associated fear memory, while US retrieval before extinction (US + Ext) could prevent multiple CS–associated fear memory with that US (5). Although it is reported that reactivation of original memory engrams in the dentate gyrus (DG) contributes to remote contextual fear memory attenuation (6), little is known whether the coding pattern of memory engrams is altered during post-retrieval extinction–induced memory updating.

Memory engram cells referred to a population of neurons that are activated by learning and must be reactivated for recall (7). In the contextual fear memory paradigm, previous studies found that artificial activation of engram cells could induce stored memory retrieval, and extinction training suppressed the reactivation of original engram cells while activating distinct extinction engram ensembles in the DG (7–9). Moreover, fear and extinction cells were also found in basolateral amygdala (BLA), and the balance of activity between subpopulations of BLA projection neurons determines the relative expression of fear and extinction memories (10, 11). It is reported that prelimbic cortex (PrL) is critical for auditory fear memory expression, and the existence of fear engram cells in PrL is well established (12, 13). However, whether there exist extinction cells in PrL remains unknown. In addition, the relationship between fear and extinction cells and the dynamic modification of fear engram encoding underlying memory updating are still unclear. In particular, whether memory erasure is mediated by the inhibition or updating of fear engrams has always been a question.

To answer the question, by using activity-dependent neuronal-tagging technology, neuronal tracing technique combined with optogenetic manipulation and in vivo calcium imaging (7, 14, 15), we identified the fear and extinction cells in PrL and BLA and investigated the dynamic encoding of memory engram ensembles in PrL and BLA during CS- versus US-initiated memory updating.

RESULTS

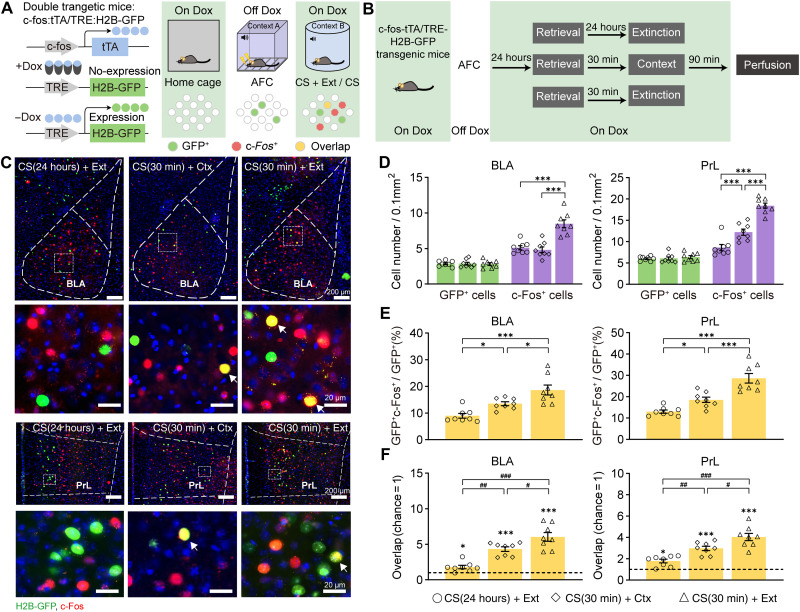

First, the mice were fear-conditioned using three tone-shock pairings and were then divided into four experimental groups. Context only, extinction only, CS(30 min) + Ext, and CS(24 hours) + Ext groups were included to examine whether time window–controlled post-retrieval extinction paradigm could erase fear memory. Consistent with previous study (3), SR, renewal, and reinstatement were found in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group but not in the CS(30 min) + Ext group (fig. S1, A to C). In addition, memory saving could be tested by retraining to determine whether memory was erased (3), and we found that the freezing levels during the memory saving test performed at 24 hours after retraining in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group were significantly higher than those in home cage and CS(30 min) + Ext groups. Moreover, there was no difference in the memory saving test between the CS(30 min) + Ext group and the home cage group, which suggests that there was no memory savings in the CS(30 min) + Ext group (fig. S1D). These results suggested that the CS(30 min) + Ext paradigm could erase fear memory. While BLA, PrL, and infralimbic cortex (IL) have been reported to be respectively involved in cued fear learning, retrieval, and extinction processes (16, 17), it remains unknown whether they play roles in memory erasure. Therefore, we examined the c-Fos expression at 90 min after the CS + Ext paradigm and found that PrL and BLA but not IL showed increased c-Fos–positive cell numbers in the CS(30 min) + Ext group compared with the CS(24 hours) + Ext group (fig. S1, E and F). Next, we want to know whether the reactivation of fear engram cells contributes to the increased c-Fos expression during memory erasure. We used double transgenic c-fos:tTA and TRE:H2B-GFP TetTag mice and c-Fos antibody to label and detect the memory engram cell reactivation during memory erasure. By using doxycycline (Dox)–dependent manner, the mice underwent auditory fear conditioning (AFC) training under the Dox-off condition to label the fear memory engram cells, and the cells activated by extinction, retrieval, or erasure were labeled with the c-Fos antibody, where the GFP+c-Fos+ cells indicate the reactivated engram cells (Fig. 1, A to C). In BLA and PrL, the GFP+ cell number showed no difference between CS(30 min) + Ext, CS(30 min) + Ctx, and CS(24 hours) + Ext groups (Fig. 1D). The engram cell reactivation ratio in the CS(30 min) + Ctx group was significantly higher than that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group; however, the CS(30 min) + Ext group showed the highest engram reactivation ratio among the three groups (Fig. 1E). In addition, in both BLA and PrL, the engram cell reactivation was above chance in either the CS(24 hours) + Ext group, the CS(30 min) + Ctx group, or the CS(30 min) + Ext group, and the reactivation in the CS(30 min) + Ext group was significantly greater than that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext or CS(30 min) + Ctx group (Fig. 1F). These findings indicate the increased memory engram cell reactivation in BLA and PrL during memory erasure, which might contribute to CS-initiated memory updating.

Fig. 1. The engram cells in BLA and PrL show increased reactivation during CS-initiated memory updating.

(A) Labeling strategy of the inducible double transgenic TetTag mouse and the experimental design used in the CS or CS + Ext paradigm. Activated neurons upon AFC training express H2B-GFP (green), while neurons activated by CS or CS + Ext express endogenous c-Fos (red) and the overlapped cells were labeled (yellow). (B) Experimental schedule of engram cell labeling in CS(24 hours) + Ext, CS(30 min) + Ctx, and CS(30 min) + Ext groups. (C) Representative images of GFP+ (green) and c-Fos+ (red) immunofluorescence in BLA (top) and PrL (bottom) during CS(30 min) + Ext, CS(30 min) + Ctx, and CS(24 hours) + Ext. The white arrowheads marked colabeled GFP+c-Fos+ cells. (D) The CS(24 hours) + Ext, CS(30 min) + Ctx, and CS(30 min) + Ext groups showed similar GFP+ cell density, but the c-Fos+ cell density was significantly higher in the CS(30 min) + Ext group in both PrL and BLA (unpaired t test, ***P < 0.001; n = 8 animals per group). (E) GFP+c-Fos+/GFP+ levels were significantly higher in the CS(30 min) + Ext group than in CS(24 hours) + Ext and CS(30 min) + Ctx groups [one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001]. (F) Compared with the chance (dashed line) level, the overlap between GFP+ and c-Fos+ cells [GFP+c-Fos+/4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)] was greater in CS(30 min) + Ext, CS(30 min) + Ctx, and CS(24 hours) + Ext groups, but the overlap was higher in the CS(30 min) + Ext group than in the CS(30 min) + Ctx or CS(24 hours) + Ext group (paired t test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

The activation of fear engram cells in PrL but not BLA is crucial for CS-initiated memory updating

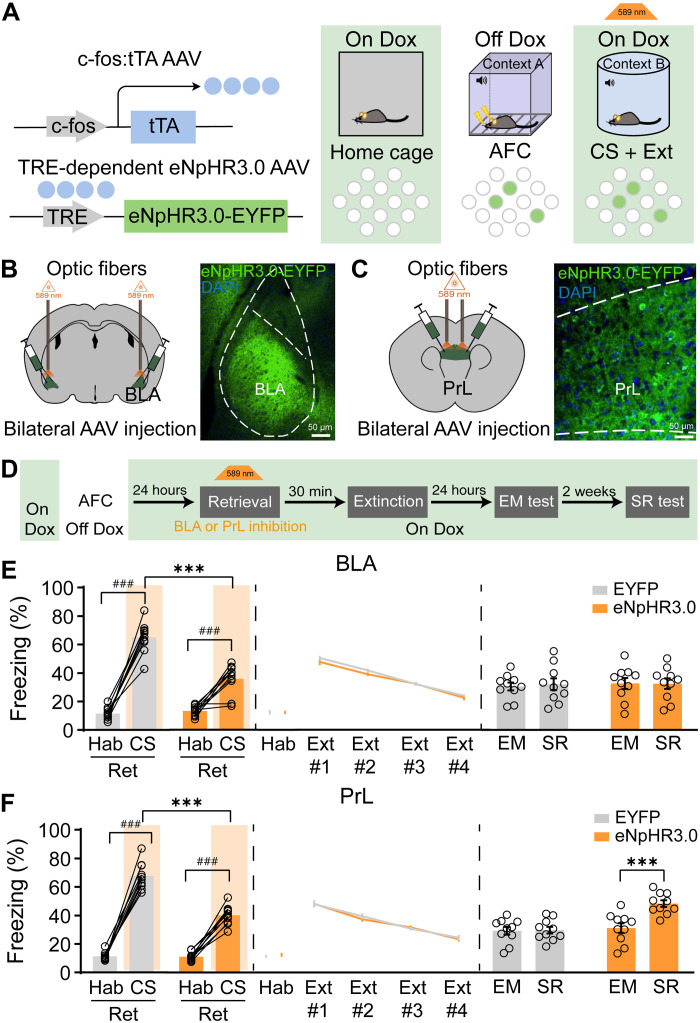

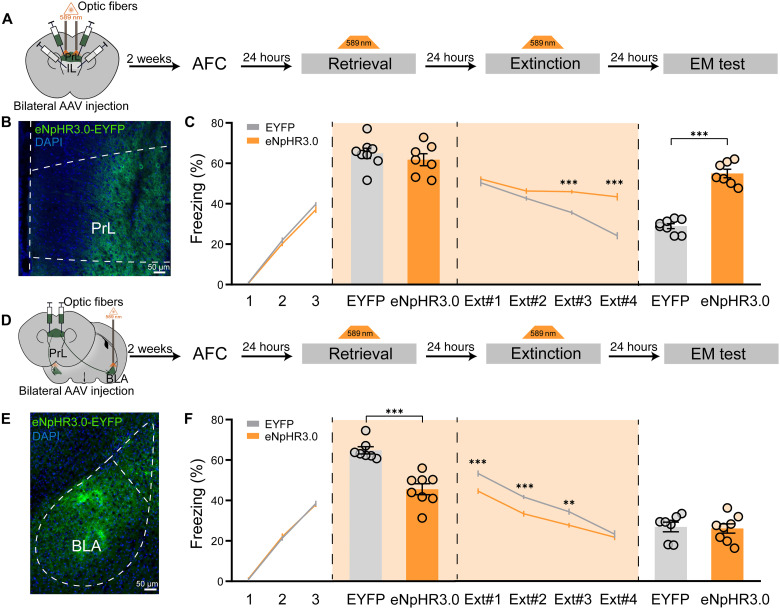

To investigate the role of BLA and PrL engram cells in CS-initiated memory updating, we first bilaterally targeted injections of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:eNpHR3.0-EYFP into BLA or PrL of wild-type (WT) mice to label the fear engram cells induced by AFC training (Fig. 2, A to C). Optogenetic inhibition of BLA or PrL fear engram cells during retrieval could significantly decrease the freezing levels in the retrieval test, while it has no effect on the following extinction performance (Fig. 2, D to F). Optogenetic inhibition of PrL but not BLA fear engram cells during retrieval led to increased freezing levels during the SR test, indicating fear memory recovery (Fig. 2, E and F). It suggests that both BLA and PrL fear engram cells are necessary for fear memory retrieval, while fear engram cells in PrL but not BLA are essential for CS-initiated memory updating.

Fig. 2. The activation of engram cells in PrL but not BLA was necessary for CS-initiated fear memory updating.

(A) Labeling strategy of engram cells with eNpHR3.0-EYFP. (B) Coronal sections of BLA with eNpHR3.0-EYFP (green). (C) Coronal sections of PrL with eNpHR3.0-EYFP (green). (D) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic inactivation of engram cells in BLA or PrL. (E) Optogenetic silencing of engram cells in BLA during retrieval (Ret) reduced the freezing levels (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; paired t test, ###P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). Freezing behavior during extinction showed no difference. The freezing levels during the SR test and EM test showed no difference. (F) Optogenetic silencing of engram cells in PrL during retrieval reduced the freezing levels (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). Freezing behavior during extinction showed no difference. The freezing levels during the SR test were significantly increased compared to the EM test by optogenetic silencing of engram cells in PrL, but there was no difference in the EYFP group [repeated-measures (RM) two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001]; freezing levels of habituation showed the freezing levels in the context during the pre-CS or preactivation period. Data are presented as means ± SEM.

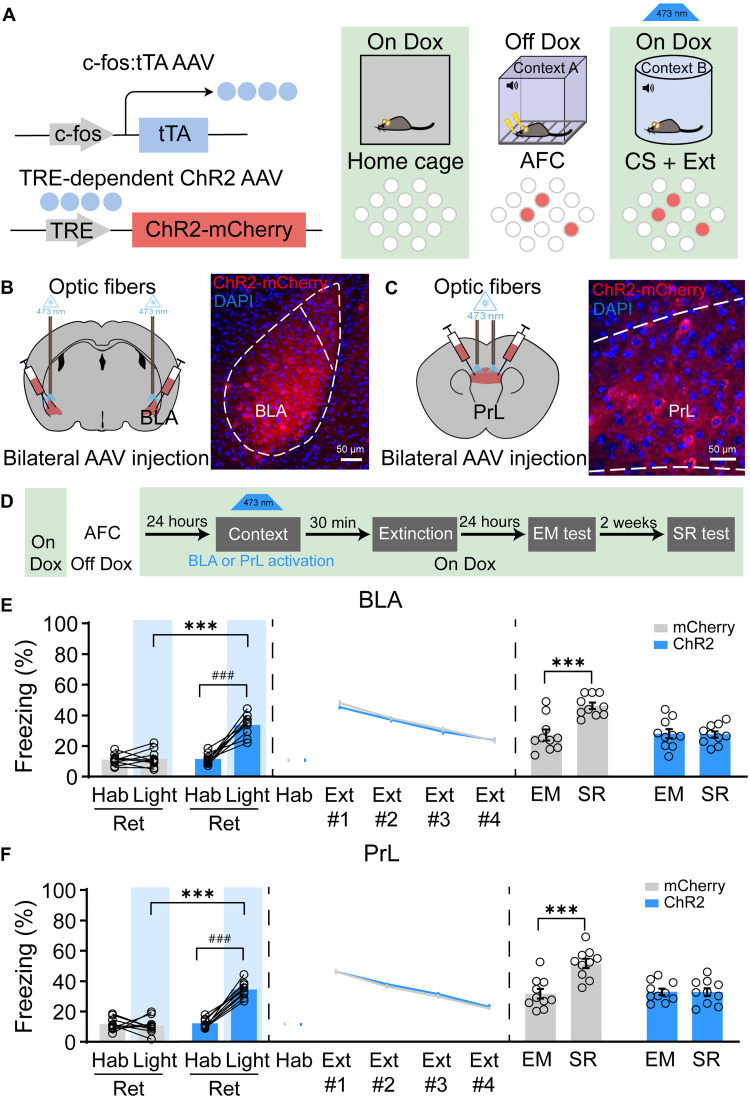

To further investigate whether artificially activating BLA or PrL fear engram cells 30 min before Ext could induce memory erasure, we labeled the BLA or PrL engram cells induced by AFC training by bilaterally targeted injections of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry (Fig. 3, A to C). Optogenetic activation of BLA or PrL fear engram cells in the context B without CS recall at 30 min before Ext could induce freezing behavior and has no effect on the following extinction training (Fig. 3, D to F), which is consistent with previous study that artificial activation of memory engram cells could induce memory expression (8). Moreover, there is no freezing recovery during the SR test following optogenetic activation of BLA or PrL fear engram cells at 30 min before extinction (Fig. 3, E and F). To rule out the influence of single CS retrieval or optogenetic activation of fear engrams on the subsequent memory test, we further analyzed the freezing levels during the first trail of Ext in different experimental groups. The freezing levels during the first trail of Ext exactly reflect the memory levels without extinction. Therefore, analyzing the freezing levels during the first trail of Ext in Ext only, CS(24 hours) + Ext, and CS(30 min) + Ext groups (data from fig. S1) could investigate the effect of CS retrieval only on the subsequent memory test. The freezing levels during the first trail of Ext in the optogenetic activation of the PrL or BLA engrams (data from Fig. 3) could reveal the effect of optogenetic manipulation on the subsequent memory test. We found that the freezing levels were no different across Ext only, CS(24 hours) + Ext, and CS(30 min) + Ext groups, which suggests that single CS exposure during the retrieval session could not affect the subsequent fear memory test (fig. S2A). Similarly, the freezing levels during the first trail of Ext showed no difference between the ChR2 group and the mCherry group under the PrL or BLA engram manipulation (fig. S2B). These results suggest that neither single CS exposure nor single optogenetic activation of memory engrams could affect the subsequent fear memory test. Together, our results suggest that BLA or PrL fear engram cell activation at 30 min before extinction is sufficient for CS-initiated memory updating.

Fig. 3. The activation of engram cells in either PrL or BLA could induce CS-initiated fear memory updating.

(A) Labeling strategy of engram cells with ChR2-mCherry. (B) Coronal sections of BLA with ChR2-mCherry (red). (C) Coronal sections of PrL with ChR2-mCherry (red). (D) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic activation of engram cells in BLA or PrL. (E) Optogenetic activation of engram cells in BLA in context B without CS-induced increased freezing levels (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; paired t test, ###P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). Freezing behavior during extinction showed no difference. The freezing levels during the SR test were significantly increased compared to the EM test in the mCherry group, but there was no difference in the ChR2-mCherry group in which the engram cells in BLA were activated by optogenetics (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001). (F) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic activation of engram cells in PrL. Optogenetic activation of engram cells in PrL in context B without CS-induced increased freezing levels (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; paired t test, ###P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). Freezing behavior during extinction showed no difference. The freezing levels during the SR test were significantly increased compared to the EM test in the mCherry group, but there was no difference in the ChR2-mCherry group in which the engram cells in PrL were activated by optogenetics (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

To clarify the differential role of PrL and BLA fear engram cells in CS-initiated memory updating, we bilaterally targeted injections of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry into PrL for fear engram cell activation, and AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:eNpHR3.0-EYFP were simultaneously injected into BLA for fear engram cell inhibition (fig. S3A). Activation of PrL fear engram cells and simultaneous inhibition of BLA engram cells at 30 min before extinction did not induce freezing behavior in the retrieval test, while it could block freezing recovery during the SR test, indicating erased fear memory (fig. S3B). We next inhibited the PrL fear engram cells and simultaneously activated BLA engram cells at 30 min before extinction; mice freezing levels in the retrieval test were significantly increased compared with the control group (fig. S3, C and D). However, freezing levels during the SR test were increased compared with that during the extinction memory (EM) test, indicating fear memory recovery (fig. S3D). Thus, our data suggest that the activation of BLA engram cells is critical for fear expression but not CS-initiated memory updating, whereas the activation of PrL fear engram cells is necessary and sufficient for CS-initiated memory updating. Our data also demonstrate that it is the activation of fear engram cells but not the freezing behavior that is critical for fear memory updating. To illustrate the mechanism that artificial activation of BLA fear engram cells could induce memory erasure, we further bilaterally injected AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry into BLA in double transgenic c-fos:tTA and TRE:H2B-GFP TetTag mice, which could allow us to examine the PrL engram cell reactivation upon BLA engram cell activation (fig. S3E). BLA fear engram cells induced by AFC training were labeled by ChR2-mCherry, and optogenetic activation of BLA engram cells could induce increased freezing levels in the context without CS recall (fig. S3, F and G). Furthermore, we found that the c-Fos expression and the engram cell reactivation in PrL were increased upon optogenetic activating BLA engram cells (fig. S3, H and I), which suggests the functional connection between BLA and PrL fear engram cells and is consistent with our conclusion that the activation of PrL engram cells is critical for CS-initiated memory updating.

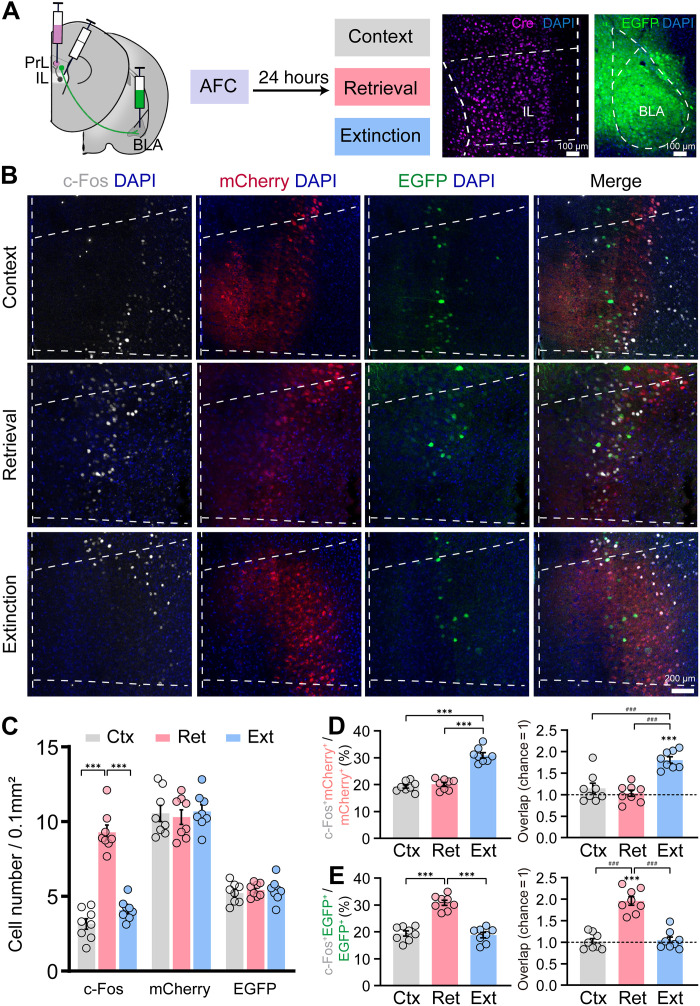

Identification of extinction cells in PrL

Contextual extinction training has been reported to induce the activation of extinction cells, which shows high reactivation and suppresses the reactivation of fear cell ensembles in the EM test (9). We hypothesized that the cross-talk between fear and extinction ensembles may be critical for memory updating. As reported, fear cells and extinction cells have been identified in BLA, whereas PrL was reported to be involved in memory expression via inputs to BLA but not extinction (11). A recent study described that extinction ensembles existed in the medial prefrontal context (mPFC), and they found that the extinction engram connectivity of BLA → mPFC and ventral hippocampus (vHPC) → mPFC is available but weakened during fear recovery. However, the subregion of mPFC was not clarified in their study, and whether there exist extinction ensembles in PrL remains unclear (18). Previous studies showed that the IL plays an essential role in memory extinction (19–21), and IL efferent into PrL is required for extinction learning in traced fear conditioning (16, 22). Therefore, we injected the retrograde virus AAV2-hSyn-EGFP into BLA to label the BLA projecting PrL cells (EGFP+) and simultaneously injected the anterograde trans-synaptic virus AAV1-hSyn-Cre into IL and AAV9-DIO-mCherry into PrL to label the PrL cells receiving IL projections (mCherry+). Mice were subjected to the AFC training after 2 weeks and divided into three groups for context only: retrieval and extinction treatment followed by c-Fos immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 4, A and B). Consistent with our previous data (fig. S1, F and G), the c-Fos cell number in the retrieval group was increased compared with those in context only and extinction groups (Fig. 4C). The c-Fos cell number in the extinction group showed an increased trend (P = 0.1821) but did not reach statistic difference compared with the context only group. Next, we analyzed the c-Fos+mCherry+ and c-Fos+EGFP+ colabeled cell number across groups. We found that the number of mCherry+ and EGFP+ cells showed no difference across groups, whereas the percentage of colabeled c-Fos+mCherry+ cells was higher in the extinction group compared with context only and retrieval groups (Fig. 4, C and D). Moreover, the overlap level of c-Fos+mCherry+ cell during extinction was significantly higher than that in context and retrieval (Fig. 4D). In contrast, the percentage of colabeled c-Fos+EGFP+ cells and the overlap level of c-Fos+EGFP+ cells were significantly higher in the retrieval group compared with context only and extinction groups (Fig. 4E). These results suggest that PrL cells receiving IL projections displayed increased activation during extinction, while PrL cells projecting to BLA were activated during retrieval. We next investigate the functional roles of these two cell populations by optogenetics. AAV1-hSyn-Cre was injected into IL, AAV9-DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP was injected into PrL, and the optic fiber was implanted into PrL to manipulate PrL cells receiving IL projections (Fig. 5, A and B). AAV9-hSyn-eNpHR3.0-EYFP was injected into PrL, and the optic fiber was implanted into BLA to manipulate the PrL-BLA projections (Fig. 5, D and E). We found that inhibition of PrL cells receiving IL projections has no effect on memory retrieval but impairs extinction performance, while inhibition of PrL-BLA projections impairs memory retrieval but has no effect on the rate of within-session extinction and EM test (Fig. 5, C and F). These data suggest that there were two distinct ensembles in PrL, where BLA projecting PrL neurons were mainly responsible for fear encoding, while PrL neurons receiving IL inputs were involved in memory extinction.

Fig. 4. PrL neurons receiving IL inputs showed high activation during memory extinction.

(A) Labeling strategy of the anterograde and retrograde tracing in PrL and the behavioral experimental design; coronal sections of IL with anti-Cre immunostaining (left) and coronal sections of BLA with retroAAV2-hSyn-EGFP expression (right). (B) Representative images of c-Fos+ (white), mCherry+ (red), and EGFP+ (green) cells in PrL during context, retrieval, and extinction. (C) The three groups (Ctx, context; Ret, retrieval; Ext, extinction) showed similar mCherry+ and EGFP+ cell density, but the c-Fos+ cell density during retrieval was significantly higher than in context and extinction groups (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 8 animals per group). (D) c-Fos+mCherry+/mCherry+ levels were significantly higher in the extinction group than in context and retrieval groups; compared with the chance (dashed line) level, the overlap between mCherry+ and c-Fos+ cells (c-Fos+mCherry+/DAPI) was greater in the extinction group, and the overlap was higher in the extinction group than in context and retrieval groups (paired t test, ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ###P < 0.001). (E) c-Fos+EGFP+/EGFP+ levels were significantly higher in the retrieval group than in context and extinction groups; compared with the chance (dashed line) level, the overlap between EGFP+ and c-Fos+ cells (c-Fos+EGFP+/DAPI) was greater in retrieval groups, and the overlap was higher in the retrieval group than in context and extinction groups (paired t test, ***P < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ###P < 0.001). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Fig. 5. PrL neurons receiving IL inputs regulate memory extinction.

(A) Labeling strategy of PrL neurons receiving IL projection with injection of DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP in PrL and injection of AAV1-hSyn-Cre in IL; schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic inactivation of PrL neurons receiving IL projection. (B) Coronal sections of PrL with DIO-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (green). (C) Optogenetic inhibition of PrL neurons receiving IL projection has no effect on retrieval but impairs EM acquisition, and the freezing levels during the EM test were significantly increased in the eNpHR3.0 group compared to the EYFP group (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 8 animals in the EYFP group, n = 7 animals in the eNpHR3.0 group). (D) Labeling strategy of PrL projections into BLA with injection of AAV9-hSyn-eNpHR3.0-EYFP in PrL; schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic inactivation of PrL to BLA projections. (E) Coronal sections of BLA with PrL axons expressing eNpHR3.0-EYFP (green). (F) The freezing levels during retrieval were significantly decreased in the eNpHR3.0 group compared with the EYFP group. The freezing levels during Ext#1, Ext#2, and Ext#3 in the eNpHR3.0 group were significantly lower than those in the EYFP group, while the rate of within-session extinction showed no difference (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 8 animals per group). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

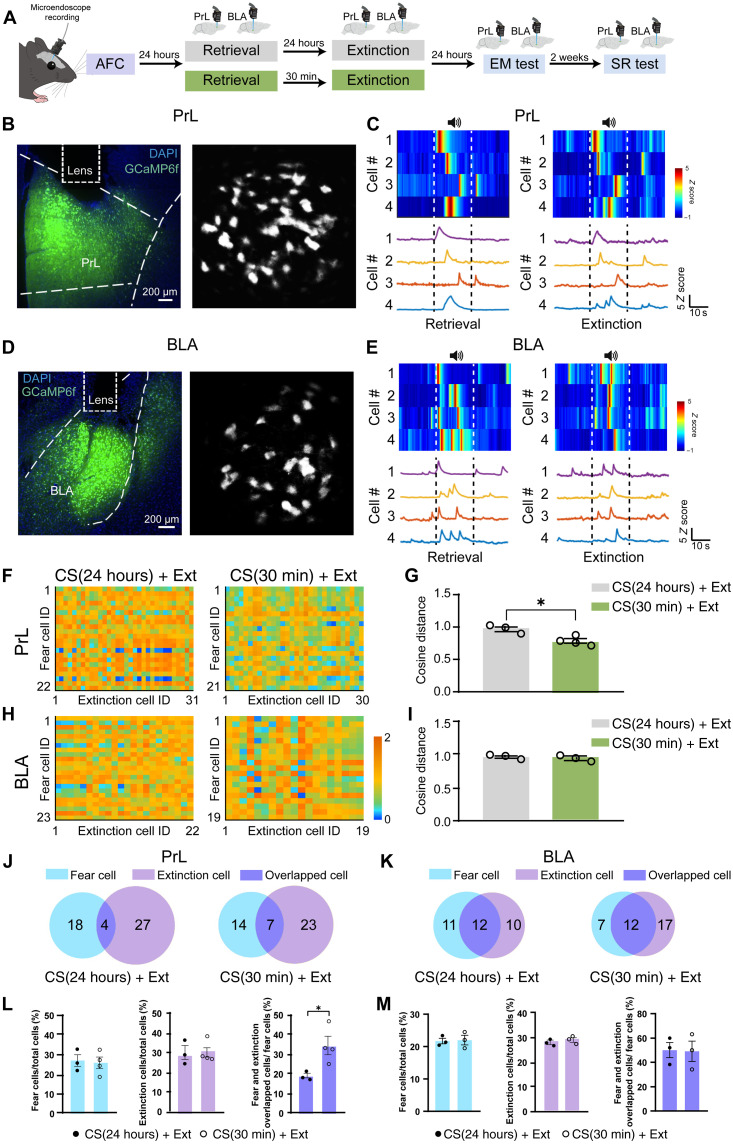

CS-initiated memory updating induced increased fear and extinction overlapping ensembles in PrL but not BLA

To further investigate the cross-talk between fear and extinction cells, we monitor Ca2+ activity at the single-cell level in PrL and BLA of freely moving mice by using miniaturized microscope. We injected AAV5-hSyn-GCaMP6f into PrL or BLA of WT mice and implanted a graded refractive index (GRIN) lens (Fig. 6, A, B, and D). After enough recovery time, the mice experienced the AFC training followed by memory extinction or erasure paradigm (Fig. 6A). We functionally identified fear cells and extinction cells in PrL and BLA (Fig. 6, C and E). Fear cells were selectively activated during fear retrieval, while extinction cells were selectively activated during the last trial of extinction, which is according to the definition of a previous study (23). To examine the relationship between fear and extinction cells during memory extinction or erasure, we calculated the vector distance by cosine distance between fear and extinction cells in PrL and BLA (Fig. 6, F to I), which allowed us to analyze the similarity of population activity patterns between fear and extinction cells (24). Cosine distance is good for the analysis of population activity pattern structure as it is independent of activity intensity. We found that the cosine distance between fear and extinction cells in the CS(30 min) + Ext group was smaller than that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group in PrL, while there is no difference in BLA (Fig. 6, G and I). These data suggest that population activity patterns between fear and extinction cells were much more closely related during CS-initiated memory updating compared with that during memory extinction in PrL but not in BLA. The discrepancy in population activity similarity between fear and extinction cells in PrL and BLA during CS-initiated memory updating may explain the differential role of fear engrams in PrL and BLA in memory updating.

Fig. 6. The vector distance and overlapped cells between fear cells and extinction cells during CS-initiated memory updating.

(A) Monitoring of Ca2+ activity of PrL and BLA during different behavioral paradigm in a freely moving mouse by using miniaturized microscope. (B) Virus injection and GRIN lens implantation (left) and maximum intensity projection image (right) in PrL. (C) Example cells selected activated during retrieval or the last trail of extinction in PrL. (D) Virus injection and GRIN lens implantation (left) and maximum intensity projection image (right) in BLA. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Example cells selected activated during retrieval or the last trail of extinction in BLA. The matrix showed the cosine distance from example mice between fear cells and extinction cells in PrL (F) or BLA (H) in CS(24 hours) + Ext and CS(30 min) + Ext groups. (G) The cosine distance between fear and extinction cells of PrL in the CS(30 min) + Ext group was significantly smaller than that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group [two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05; n = 3 animals; 335 neurons in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group; n = 4 animals, 434 neurons in the CS(30 min) + Ext group]. (I) The cosine distance between fear and extinction cells of BLA showed no difference between CS(24 hours) + Ext and CS(30 min) + Ext groups [n = 3 animals, 396 neurons in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group; n = 3 animals, 375 neurons in the CS(30 min) + Ext group]. The Venn map showed the distribution of fear and extinction cells in PrL (J) or BLA (K) from example mice in CS(24 hours) + Ext and CS(30 min) + Ext groups. The percentage of fear cells (fear cells/total cells), extinction cells (extinction cells/total cells), and overlapped cells (fear and extinction overlapped cells/fear cells) of the CS(30 min) + Ext group in PrL (L) or BLA (M) (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

With the greater similarity between fear and extinction cells in PrL during CS-initiated memory updating, we asked whether there were overlapping ensembles in memory updating, as it was reported that overlapping ensembles could alter the fear memory (25). The Venn diagram showed the number of fear cells, extinction cells, and overlapped cells in example mice in the memory extinction or CS updating group, respectively (Fig. 6, J and K). We found that the overlapped percentage of fear and extinction cells in PrL was higher in the CS(30 min) + Ext group compared with that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group, although the percentage of fear or extinction cells was similar (Fig. 6L). Unexpectedly, neither the percentage of fear or extinction cells nor the overlapped percentage was different between CS(24 hours) + Ext and CS(30 min) + Ext groups in BLA (Fig. 6M), which suggested that the overlapping ensembles in PrL might be the mechanism underlying CS-initiated memory updating.

The original fear engram encoding in PrL was altered during CS-initiated memory updating

Having known that there is increased similarity and overlapping between fear cells and extinction cells during CS-initiated memory updating in PrL but not in BLA, we hypothesized that the original fear cell ensembles in PrL but not BLA were remodeled during CS-initiated memory updating. We first analyzed the reactivation of fear and extinction cells during different sessions to support our hypothesis. In the CS(24 hours) + Ext group, compared with those during the first trial of extinction, we found that the reactivation of fear cells was decreased with extinction training in both PrL and BLA, while it showed recoverable reactivation during SR (fig. S4, A and D). In addition, extinction cell reactivation in both PrL and BLA during SR was significantly lower than that during the EM test, which suggests that fear cell reactivation was positively related with the freezing level, while extinction cell reactivation was negatively related with freezing levels (fig. S4, B, C, E, and F). Our results were consistent with a previous study that shows that fear engrams were inhibited during EM, while the increased engram reactivation induced SR (9). Differentially, in the CS(30 min) + Ext group, the reactivation of fear cells and extinction cells in PrL showed no difference across different sessions, although the freezing levels were lower in EM and SR tests compared with the first trial of extinction (fig. S4, A to C). On the contrary, in BLA, the relationship between reactivation of fear cell and extinction cell with the freezing levels across different sessions in the CS(30 min) + Ext group was consistent with that in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group (fig. S4, E and F). These results suggested that the coding pattern of original fear cell ensembles might be altered in PrL but not in BLA during CS-initiated memory updating.

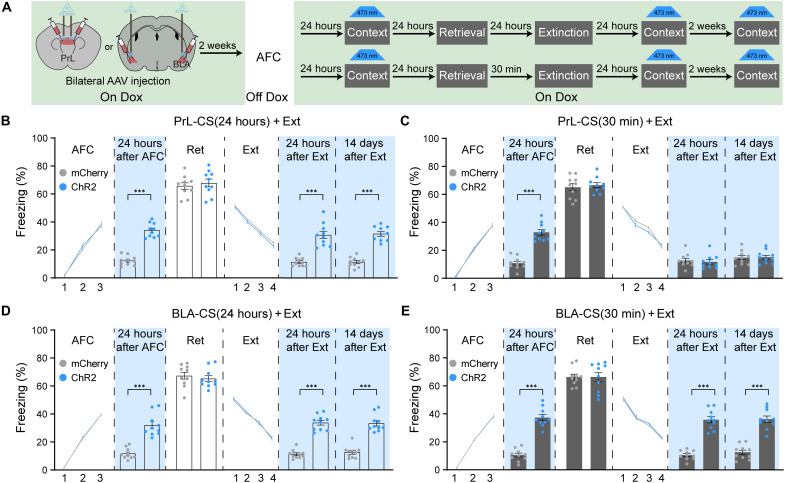

Furthermore, to provide functional evidence to support our hypothesis, we performed the optogenetic activation study. We trained four groups of mice for our manipulation, PrL-CS(24 hours) + Ext, PrL-CS(30 min) + Ext, BLA-CS(24 hours) + Ext, and BLA-CS(30 min) + Ext (Fig. 7A). With the similar training curve, similar freezing levels in the retrieval test, and similar extinction curve, we found that activation of PrL or BLA fear engram cells could induce fear memory expression either before extinction or after extinction in the CS(24 hours) + Ext group (Fig. 7, B and D). In the CS(30 min) + Ext group, activation of PrL or BLA fear cells before extinction could induce increased freezing levels (Fig. 7, C and E). However, optogenetic activation of PrL fear engram cells at 24 hours or 14 days after extinction could not induce freezing behavior, whereas BLA fear engram cell activation could still increase freezing (Fig. 7, C and E). These data provided functional evidence that the original engram coding information in PrL but not BLA was rewritten during CS-initiated memory updating.

Fig. 7. The encoding of engram cells in PrL but not BLA was updated during CS-initiated memory updating.

(A) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic activation of engram cells in PrL or BLA at different time points. The freezing levels with activation of PrL engram cells in context B without retrieval at 24 hours after AFC and 24 hours or 14 days after extinction in the PrL-CS(24 hours) + Ext group (B) and the PrL-CS(30 min) + Ext group (C) (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). The freezing levels with activation of BLA engram cells in context B without retrieval at 24 hours after AFC and 24 hours or 14 days after extinction in the BLA-CS(24 hours) + Ext group (D) and the BLA-CS(30 min) + Ext group (E) (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 10 animals per group). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

US-initiated memory updating induced increased fear and extinction overlapping ensembles in BLA

The above results were focused on the specific CS-related memory updating; next, we want to know the selectivity of the dynamic coding remodeling of the original fear cell ensembles as there were multiple CS associations to US in actual situation. Therefore, the CS1-US and CS2-US behavioral paradigm was used to investigate that the differences between memory erasure procedures depended on the post-CS extinction and post-US extinction. CS1 and CS2 were two different tones that the mouse could distinguish and learn with US association, respectively. After the fear conditioning experiment with CS1 and CS2, the mice could learn CS1- and CS2-related fear memory, respectively. Then, the post-CS or post-US extinction behavioral paradigm was applied to erase the fear memory. To clarify the difference of neural ensembles activation during CS- or US-initiated memory erasure in PrL, we tracked the Ca2+ activity of cells in PrL during post-CS or US extinction procedures (fig. S5, A and B). The behavior paradigm showed that the CS1(30 min) + Ext paradigm could specifically erase the CS1 fear memory while leaving the CS2 memory intact (fig. S5A), whereas the US(30 min) + Ext paradigm could erase both the CS1 and CS2 memory, which was consistent with previous studies (fig. S5B) (5, 26). We accordingly identified CS1 fear cells, CS2 fear cells, and CS1 extinction cells in PrL (fig. S5, C and D). Although we found that both CS1 and CS2 fear cells in PrL showed high reactivation levels during US retrieval (fig. S7A), the cosine distance between CS1 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells was smaller than that between CS2 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells in PrL in both CS1(30 min) + Ext and US(30 min) + Ext groups (fig. S5, E and F). Furthermore, the overlapped percentage of CS1 fear and CS1 extinction cells in PrL was greater than that of CS2 fear and CS1 extinction cells in both CS1(30 min) + Ext and US(30 min) + Ext groups (fig. S5, G and H). These results provide another evidence to support the essential role of increased fear and extinction overlapping ensembles in PrL for specific CS but not US retrieval–initiated memory updating.

Then, we tracked the Ca2+ activity of cells in BLA during the CS1- and US-initiated memory updating paradigm, and the CS1 fear, CS2 fear, and CS1 extinction cells in BLA were identified (Fig. 8, A to D). We found that the reactivation of both CS1 and CS2 fear cells in BLA was higher than by chance during US retrieval (fig. S7B). In the CS1(30 min) + Ext group, we found that the cosine distance between CS2 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells showed no difference compared with that between CS1 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells in BLA. In contrast, the cosine distance between CS1/CS2 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells in BLA in the US(30 min) + Ext group was smaller compared with that in the CS1(30 min) + Ext group (Fig. 8, E and F). In addition, the overlapped cells between CS1/CS2 fear and CS1 extinction cells in BLA in the US(30 min) + Ext group were increased compared with those in the CS1(30 min) + Ext group (Fig. 8, G and H). These data further confirm that the overlapping ensembles between fear and extinction cells were essential for post-retrieval memory updating and suggest that CS- versus US-initiated memory updating occurred in PrL and BLA, respectively.

Fig. 8. The vector distance and overlapped cells between fear cells and extinction cells in BLA during US-initiated memory updating.

Monitoring of Ca2+ activity of BLA during different sessions of CS1(30 min) + Ext (A) or US(30 min) + Ext (B) in a freely moving mouse by using miniaturized microscope (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001). Example cells selected activated during CS1 retrieval, CS2 retrieval, and the last trail of CS1 extinction in BLA during CS (C)– or US (D)–initiated memory updating. (E) The matrix showed the cosine distance from one example mouse between CS1 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells and CS2 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells of BLA. (F) Compared with the CS1(30 min) + Ext group, CS1 fear cells and CS1extinction cells or CS2 fear cells and CS1 extinction cells showed closer cosine distance in the US(30 min) + Ext group [two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05; n = 3 animals, 320 neurons in the CS1(30 min) + Ext group; n = 3 animals, 328 neurons in the US(30 min) + Ext group]. (G) The Venn map showed the distribution of CS1 fear cells, CS2 fear cells, and CS1 extinction cells in BLA from one example mouse. (H) The percentage of CS1 and CS2 fear cells (fear cells/total cells) in BLA showed no difference. Compared with the CS1(30 min) + Ext group, the percentage of CS2 fear cells or CS1 fear cells and CS1 extinction overlapped cells (fear and extinction overlapped cells/fear cells) in the US(30 min) + Ext group was significantly higher (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, *P < 0.05). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

Next, we performed the optogenetic experiment to investigate the functional role of BLA engram cells in US-initiated memory updating. The BLA engram cells induced by CS1-US or CS2-US training was labeled by bilateral injection of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:eNpHR3.0-EYFP (fig. S6A). Optogenetic inhibition of either CS1 or CS2 engram cells in BLA during US retrieval has no effect on CS1 extinction but increases the freezing levels in the SR test, which suggests that the activation of CS1/CS2 engram cells in BLA is necessary for US-initiated fear memory erasure (fig. S6, B and C). In addition, we analyzed the overlap of CS1 and CS2 fear cells in PrL and BLA during fear memory updating. We found that the overlap level of CS1 and CS2 fear cells in BLA was significantly higher than that in PrL, which explains how the inhibition of either CS1 or CS2 engram cells in BLA could block both CS-associated memory erasures by US(30 min) + Ext (fig. S7C).

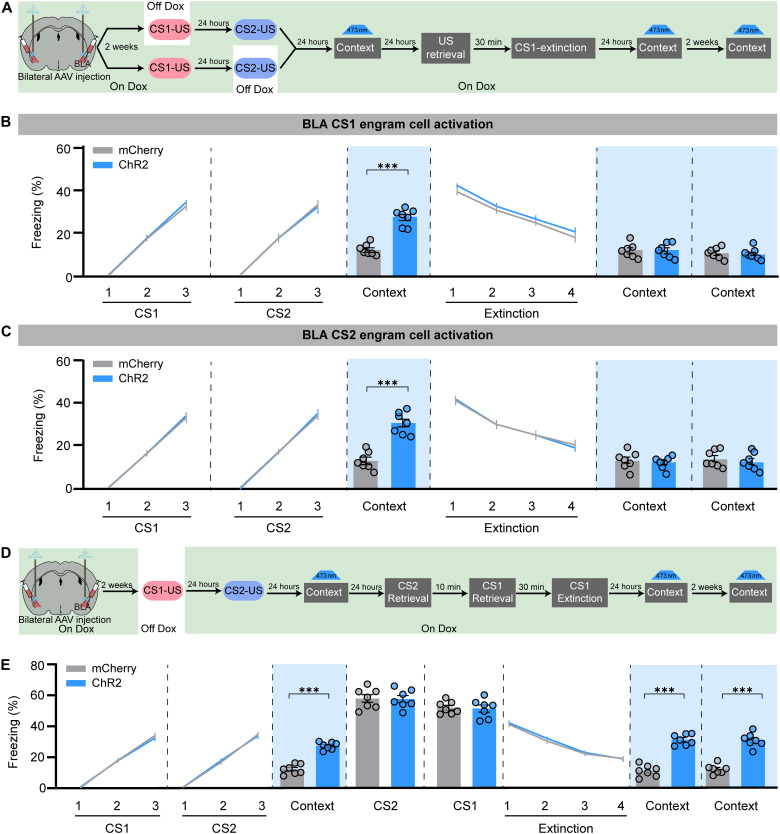

The original fear engram encoding in BLA was altered during US-initiated memory updating

We further asked whether BLA engram cell encoding was altered during US-initiated fear memory updating. We labeled BLA engram cells induced by CS1-US or CS2-US training by bilateral injection of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry (Fig. 9A). With the similar training and extinction curve, we found that activation of CS1 or CS2 BLA fear engram cells could induce fear memory expression before US(30 min) + Ext, while optogenetic activation of CS1 or CS2 BLA fear engram cells at 24 hours or 14 days after extinction could not induce freezing behavior upon US-initiated memory updating (Fig. 9, B and C). In contrast, activation of CS1 BLA fear engram cells either before CS1(30 min) + Ext or 24 hours or 14 days after CS1(30 min) + Ext could still induce freezing behavior in the CS-initiated memory updating group (Fig. 9D). These data suggest that the original engram coding information in BLA was rewritten in US-initiated memory updating but not in CS-initiated memory updating. To explore the mechanism underlying US-initiated memory updating in BLA, we compared the BLA activation pattern by c-Fos staining after CSs retrieval or US retrieval (fig. S8A). We found that CS2 and CS1 retrieval induced increased c-Fos+ cells in BLA compared with the context only group, while the c-Fos+ cell number in US retrieval was significantly greater than that during CS2 and CS1 retrieval (fig. S8, B and C). These data suggest that US retrieval may induce a more generalized BLA activation, which might account for the phenomena that US instead of CS retrieval could induce BLA engram encoding updating. Last, we labeled the activated cells during US retrieval in BLA by bilateral injection of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry into BLA (fig. S8D). We optogenetically activated these US-activated cells for 20 s at 30 min before extinction, which could increase the freezing levels and has no effect on CS1 extinction performance. However, we found that the freezing levels at the CS2 EM test and CS1 and CS2 SR tests were lower in the ChR2 group compared with the mCherry group, which suggest that activation of US-induced engram cells 30 min before extinction could induce US-initiated memory updating (fig. S8E). Moreover, artificial activation of US-induced engram cells at 24 hours or 14 days after extinction could still induce freezing behavior, which suggest that the innate US fear cells in BLA were unable to reverse the valence but might contribute to the reshaping of memory engram cells. Overall, our data show the physiological and functional evidence to support our hypothesis that the original fear cell ensemble coding pattern in PrL was remodeled during CS-initiated memory erasure, while US-initiated memory erasure induced BLA engram encoding updating.

Fig. 9. The encoding of fear engram cells in BLA was altered during US-initiated memory updating.

(A) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic activation of CS1 or CS2 engram cells in BLA at different time points. The freezing levels with activation of CS1 fear engram cells (B) or CS2 engram cells (C) in BLA in context B without retrieval at 24 hours after CS2-US conditioning and 24 hours or 14 days after extinction during US-initiated memory updating (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 7 animals per group). (D) Schematic and experimental design of the optogenetic activation of CS1 engram cells in the BLA at different time points during CS1(30 min) + Ext. (E) The freezing levels with activation of CS1 fear engram cells in BLA in context C without retrieval at 24 hours after CS2-US conditioning and 24 hours or 14 days after extinction during CS1-initiated memory updating (RM two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, ***P < 0.001; n = 7 animals per group). Data are presented as means ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

We first investigated the role of PrL and BLA engram cells in memory updating. It is reported that reactivation of memory engrams in the DG is critical for remote contextual fear attenuation (6), which suggests that fear attenuation might involve memory engram ensemble updating, but little is known about the role of engram cells in memory erasure. Instead, we found that, compared with extinction alone, the post-CS extinction paradigm induced increased auditory fear engram cell reactivation in PrL and BLA. Notably, we demonstrated that manipulating fear engram cells in PrL but not BLA could bidirectionally regulate CS-initiated memory erasure. The BLA engram cells have been reported to play an essential role in fear memory acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval (27). We found that the reactivation of BLA fear ensemble is indispensable for US- but not CS-initiated memory updating. Inhibiting BLA fear engram cells during CS retrieval blocked freezing but could still induce memory erasure. In contrast, activating BLA fear engram cells while inhibiting PrL fear engram cells induced freezing behavior but blocked memory erasure, which suggested that the reactivation of PrL engrams but not the freezing level is essential for CS-initiated memory updating. In contrast, inhibiting BLA fear engram cells blocked US-initiated fear memory updating. These studies suggested that CS- and US-initiated memory updating depends on the reactivation of engram cells in PrL or BLA, respectively.

Next, our present work demonstrated that the increased overlapping ensembles between fear and extinction cells are essential for memory updating. A previous study found that contextual extinction training suppresses reactivation of the fear acquisition ensemble and recruits a different EM ensemble in DG, which is examined at the EM test and SR stage (9). The activation of fear cells induces fear memory expression, while the activation of extinction cells promotes EM expression. It is reported that distinct BLA neurons encode fear and extinction (10, 11). Recently, BLA pyramidal neurons were found to be composed of two genetically, functionally, and anatomically distinct neuronal populations, which encode positive and negative valences, respectively (28). Further study found that BLA fear EM engram is formed and stored in the positive valence encoding cells, which express protein phosphatase 1-regulatory inhibitor subunit 1B (Ppp1r1b+) (29). A previous study showed that PrL was crucial for memory expression but not extinction (30); here, we found that BLA projecting PrL neurons mainly encode fear expression, while PrL neurons receiving IL inputs were highly activated in memory extinction and were essential for memory extinction, which provides functional evidence that extinction cells in PrL exist. Our data indicate that there were distinct fear and extinction ensembles in PrL, which provides a basis for the fear and extinction ensemble interaction and information updating in PrL.

Using a miniature fluorescence microscope, we found that the vector distance between fear cells and extinction cells in PrL but not BLA was closer in CS-initiated memory updating compared with the extinction alone group. Moreover, CS-initiated memory updating induced significantly increased overlapping between fear and extinction cells in PrL but not BLA, which is selective to CS-specific cells. To our knowledge, it is the first evidence to show the increased overlapped ensembles between fear and extinction cells during memory updating. Memory formation is dynamic in nature, and acquisition of new information is often influenced by previous experiences. In our study, the retrieval 30 min before extinction shifted the allocation of extinction cells into previous fear cells. According to the memory allocation hypothesis (31–33), a temporary increase in neuronal excitability could bias the representation of a subsequent memory to the neuronal ensemble encoding the first memory. It is reported that the overlap between the hippocampal CA1 ensembles activated by two distinct contexts acquired within a day is higher than when they are separated by a week (34). Although fear and extinction cells encode different values, we found that CS retrieval 30 min but not 24 hours before extinction induced higher overlap between fear and extinction cells in PrL but not BLA. The increased overlap of two neuronal representations might be due to increases in intrinsic neuronal excitability triggered by activation of the transcription factor cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element–binding protein (CREB) of the first memory engram cells (31, 35–37). Fear and EM that unfold in close temporal proximity (hours apart) would share a more overlapped cell ensemble and could therefore become integrated into an intertwined mnemonic structure.

Furthermore, in contrast to CS retrieval, US-initiated memory updating could erase both CS1- and CS2-associated memory and induce increased overlapping between fear and extinction cells in BLA. Previous studies reported that US is a powerful reminder to trigger reconsolidation in the amygdala, which, when pharmacologically interfered, results in selective disruption of the multiple CS–associated memory (26, 38). During US-initiated memory updating, we found that the vector distance is closer and the overlap is greater between both CS1/CS2 fear and CS1 extinction cells in BLA compared with those during CS-initiated memory updating. In contrast, in PrL, the increased overlap and decreased vector distance were only observed between CS1 fear and extinction cells. These data suggested that in contrast to CS retrieval, US-initiated memory updating occurred in the BLA fear ensembles.

Last, our study provides an opportunity to investigate the dynamic mnemonic encoding during memory updating. How the engram cells are organized to constitute a corresponding memory is a long-lasting question. We found that the reactivation of engram cells by natural cue, US, or optogenetic manipulation could be a prerequisite for memory malleability to integrate the new information outside the original memory trace and orchestrated to constitute an updated memory. What is the underlying mechanism by which memory is encoded within the engram cells? As formalized by Morris and colleagues (39), the modification of the pattern of synaptic connections mediated by synaptic plasticity is the mechanism whereby the brain stores memory. Using synaptic optoprobe, Kasai and colleagues (40) found that the acquired motor learning was disrupted by the optical shrinkage of the potentiated spines but was not affected by the identical manipulation of spines evoked by a distinct motor task in the same cortical region, which suggests that acquired motor memory depends on the formation of a task-specific, dense synaptic ensemble. Optogenetic manipulation of the plasticity at synapses specific to one memory affected the recall of only that memory and did not affect another linked fear memory encoded in the shared ensemble (41), which suggests that synapse-specific connectivity of engram cells guarantees the identity and storage of individual memories. Using the dual-eGRASP (GFP reconstitution across synaptic partners) technique, it is reported that there is enhanced connectivity and larger spine morphology between engram cells after fear conditioning and there was weakened connectivity between engram cells after extinction (42, 43). However, the question whether the memory information was updated in memory erasure with no fear recovery was unanswered. Previous studies showed that optogenetic activation of engram cell could induce memory recovery from amnesia resulting from anisomycin-induced disruption of reconsolidation, and similar results are also found in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and infantile amnesia (44–46), which suggest that the strength of engram cell connectivity critically contributes to the memory retrieval. In contrast, we found that optogenetic activation of the PrL or BLA engram cells after CS- or US-initiated memory updating could not induce memory recovery, whereas activating the engram cells after extinction did. In addition, it has been reported that the valence associated with the hippocampal DG memory engram could be bidirectionally reversed; however, the BLA engrams were not able to reverse the valence of the memory (47). Consistent with this report, we found that the reactivation of BLA engram cells is not sufficient for the memory valence updating; however, US stimulus, which triggers a more generalized BLA activation, could induce the BLA engram encoding updating. In addition, only a part of fear cells showed increased activity at the end of extinction during CS- or US-initiated memory updating, suggesting that a part of cell activation pattern alteration might be sufficient for switching the function of the total cell ensembles, which was also reported in previous studies (34, 47).

These results provide physiological and functional evidence to support our hypothesis that memory information is stored in the specific pattern of connections among engram cells. Memory updating instead of extinction alters fear engram encoding rather than induces a memory retrieval deficit, which may result from the increased overlapping fear and extinction ensembles initiated by the CS/US representation. Moreover, CS-/US-initiated memory updating is specific to learning-associated memory encoding as the valence of innate fear engrams (shock labeled) was unchanged.

Overall, we demonstrate that memory updating reshaped the neural ensemble representations of the original memory, which depends on the overlapped ensembles between fear and extinction cells, whereas memory extinction temporarily inhibited but not reshaped the original fear cells. Our study provides some previously unidentified insights into understanding how the value of memory was updated and switched.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Adult male C57BL/6J mice, c-fos:tTA transgenic mice [The Jackson Laboratory; strain B6.Cg-Tg(Fos-tTA, Fos-EGFP*)1Mmay/J; stock number 018306], and TRE:H2B-GFP transgenic mice [The Jackson Laboratory: strain Tg(tetO-HIST1H2BJ/GFP)47Efu/J; stock number 005104] weighing between 23 and 25 g (8 weeks old) at the beginning of the experiment and mice (three to four mice per standard laboratory cage) were housed and maintained at 22° ± 2°C on a 12-hour light-dark cycle with water and food available ad libitum. Care was taken to minimize pain or discomfort for the animals. All procedures were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Shandong University.

Auditory fear conditioning

There are four groups with different behavioral treatments in our study, and all groups received AFC training. After the AFC training was performed, the mice received different treatments, which were context only, extinction only, R(30 min) + Ext, and R(24 hours) + Ext groups.

For AFC, the mice were habituated for 3 min without any stimulation in a fear conditioning box (context A, which was measured 25 cm × 25 cm × 25 cm and located inside of a custom-built sound isolation box). Each box contained a modular test cage with an electrifiable floor grid and an ambient light supply. The inner walls were painted black and were cleaned with alcohol before testing. Grid floors were connected to a scrambled shock source. Auditory stimuli were delivered via a speaker in the chamber wall. Delivery of stimuli was controlled with a personal computer and a specific software (Freezing, Panlab), and then mice were fear-conditioned with three tone (CS: 20 s, 3 kHz, 80 dB)–footshock (US: 0.75 mA, 1 s) pairings. The interstimulus interval (ITI) between each CS was 120 s. After an additional 120 s following the last shock, the mice were placed back to their home cages.

Retrieval

The retrieval session was performed 24 hours after AFC; context only and extinction only mice were put into a chamber consisting of a white box context B with different floor, color, shape, and smell from fear conditioning box context A without any stimulation for 200 s. The R(30 min) + Ext and R(24 hours) + Ext mice were presented with an isolated CS after 120-s habituation, then there was 60-s duration for resting, and the mice were returned to the home cage to wait for the extinction training.

Extinction training

Mice underwent extinction training in context B. The extinction protocol was conducted as described previously (3) with little modification. Context only mice were placed into the extinction box context B for 1880 s without any stimulation, while extinction only mice, R(30 min) + Ext mice, and R(24 hours) + Ext mice were placed into context B for 180 s, then extinction only mice received 40 tone-alone (20 s) presentations with 20-s ITIs to conform to the total number of CSs, and CS(30 min) + Ext mice and CS(24 hours) + Ext mice received 39 tone-alone (20 s) presentations with 20-s ITIs. Extinction trials were binned into Ext#1, Ext#2, Ext#3, and Ext#4, with Ext#1 representing the average of trails 1 to 9 for CS(30 min) + Ext mice and CS(24 hours) + Ext mice and trails 1 to 10 for the extinction only group, and Ext#2, Ext#3, and Ext#4 representing the average of every 10 trails of 30 trails remaining.

EM test

Twenty-four hours after extinction, the mice received four tone-alone (20 s) presentations with 30-s ITIs to measure the EM in the extinction chamber (context B).

SR test

Two weeks after the EM test, the mice received four tone-alone (20 s) presentations with 30-s ITIs to measure the SR freezing in the extinction chamber (context B).

Renewal

Twenty-four hours after the EM test, the mice were tested for the freezing for CS back in the acquisition context (context A).

Reinstatement

Twenty-four hours after the EM test, the mice received five footshocks without any CS recall. The next day, the mice were tested for the freezing levels in response to the CS in the same context.

Retraining

Twenty-four hours after the EM test, the mice were reconditioned with a single CS-US pair in context B.

Memory test

Twenty-four hours after retraining, the mice were tested for the freezing levels to CS.

CS1 and CS2 AFC

We used the CS1-US and CS2-US (CS1: 20 s, 3 kHz, 80 dB; CS2: auditory pips, 5-Hz pulses of auditory pips, 5-ms rise and fall, 20 s, 8 kHz, 80 dB; US: 0.4 mA, 1-s footshock) fear conditioning paradigm to distinguish two auditory fear memories in one mouse. On day 1, the mice were fear-conditioned with three CS1-US pairings with a 120-s ITI between each pairing in context A. Twenty-four hours later, the mice were trained with CS2-US, which was the same as CS1-US procedure in context C.

For the CS1(30 min) + Ext experiment, the mice first underwent CS2 retrieval (retrieval was performed as described above) in context B on day 3. Ten minutes later, the mice underwent CS1 retrieval, and the extinction training of CS1 was performed 30 min later. On days 4 and 5, the mice underwent CS1 retrieval and CS2 retrieval to test the CS1- and CS2-related fear memory (performed as described above). On days 17 and 18, the mice underwent memory measurement (performed as described above) to CS1 and CS2 to test the memory recovery.

For the US(30 min) + Ext experiment, the mice first underwent CS1 and CS2 retrieval with a 10-min ITI in context B on day 3. The US retrieval, in which a single US was provided, was performed, and the extinction training of CS1 was performed 30 min later in a novel context D on day 4. On days 5 and 6, the mice underwent CS1 and CS2 retrieval to test the CS1- and CS2-related fear memory. On days 18 and 19, the mice underwent memory measurement to CS1 and CS2 to test the memory recovery.

In all processes, the freezing was measured by a high-sensitivity weight transducer (load cell unit), which could record and analyze the animal movement intensity. The freezing level was scored during each experimental phase by the software (Freezing, Panlab). The freezing levels of retrieval, extinction, EM, SR, renewal, and reinstatement were scored during the presentation of the tone, while extinction trials were binned into four sessions, which was previously described in the extinction training of AFC. For the optogenetic activation experiment in Figs. 2, 5, and 7 and figs. S3 and S8, the freezing was scored during the activation period (20 s), which was the same as single CS duration. The freezing levels in the context during the pre-CS or preactivation period were scored as the freezing levels of habituation in Fig. 2 and fig. S3.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

To prepare fixed brain tissue, the mice were transcardially perfused with 0.9% normal saline and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; pH 7.4) 90 min after the behavioral treatment, and brains were removed into 4% PFA overnight at 4°C for post-fixation. Then, the brains were sliced to 40-μm coronal sections via vibratome (VT1200S, Leica, Germany) and stored in antifreeze at −20°C.

For labeling c-fos–positive cells or Cre recombinase immunostaining, sections were incubated in blocking solution [0.4% Triton X-100 and 15% donkey serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for 2 hours at room temperature and then incubated in 0.1% PBST (0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) containing anti–c-fos rabbit antibody (1:3000; 2250S, Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-Cre recombinase mouse antibody (1:500; 2250S, Cell Signaling Technology) for 12 hours at 4°C. Free-floating sections were washed three times with 0.1% PBST and then incubated with donkey anti-rabbit conjugated to Alexa 594 (1:1000 in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS; A21207; Invitrogen) and donkey anti-rabbit conjugated to Cy5 AffiniPure (1:1000 in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS; 711-175-152, The Jackson Laboratory) for c-Fos staining or donkey anti-mouse conjugated to Alexa 647 (1:1000 in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS; A31571; Invitrogen) for Cre staining for 2 hours at room temperature. Subsequently, immunolabeled sections were washed with PBS three times, mounted on slides, dehydrated, and immersed in ProLong Gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Multiple images were captured at 20× objective (pixel size, 0.65 μm) using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University.

Cell counting

For counting the c-Fos+, GFP+, EGFP+, or mCherry+ cells, six coronal BLA sections (from bregma −0.82 mm to bregma −1.94 mm) and five coronal sections containing IL and PrL (from bregma 1.94 mm to bregma 1.34 mm) were used to analyze in all experiments. The NIH ImageJ was used to count the number of c-Fos+, GFP+, or mCherry+ neurons and calculate the area of BLA, PrL, and IL in each section. Overlap in Fig. 1 was calculated by (EGFP+c-Fos+/DAPI+), while (c-Fos+/DAPI+) × (GFP+/DAPI+) was calculated as the chance level of overlap in BLA and PrL, as previously reported (7). Overlap in Fig. 2 was calculated by (EGFP+c-Fos+/DAPI+) or (mCherry+c-Fos+/DAPI+), while (c-Fos+/DAPI+) × (EGFP+/DAPI+) or (c-Fos+/DAPI+) × (mCherry+/DAPI+) was calculated as their chance level of overlap in PrL.

Stereotactic injection and fiber optic implants

The mice were fixed on a stereotaxic apparatus (RWD Life Science), while the mice were anesthetized with isoflurane on an anesthetic machine (RWD Life Science). Viruses were injected using a glass micropipette through a microelectrode holder filled with mineral oil. A microsyringe pump (Nanoliter 2010 Injector, WPI) and its controller (Micro4, WPI) were used to control the speed with 40 nl/min of the injection. The needle was slowly lowered to the target site and remained there for 10 min after the injection. For the inhibition/activation of PrL engram cells, the mice were bilaterally injected with 100 nl of pAAV9-c-fos:tTA-pA (Addgene, plasmid no. 34856) and AAV9-TRE-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (OBIO, AG26972) or AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry (OBIO, PT0515) into PrL [anterior-posterior (AP): +1.94 mm, medial-lateral (ML): ±0.5 mm, dorsal-ventral (DV): −2.1 mm] and were bilaterally implanted with optical fiber into PrL (AP: +1.94 mm, ML: ±0.5 mm, DV: −1.9 mm) under the on-Dox condition. For the inhibition/activation of BLA engram cells, the mice were bilaterally injected with 100 nl of AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE-eNpHR3.0-EYFP or AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry into BLA (AP: −1.46 mm, ML: ±0.33 mm, DV: −4.68 mm) and were bilaterally implanted with optical fiber into BLA (AP: −1.46 mm, ML: ±3.3 mm, DV: −4.4 mm) under the on-Dox condition.

For inhibition of PrL neurons receiving IL projection, 100 nl of AAV1-hSyn-Cre-pA (Taitool, S02992-1) was bilaterally injected into the IL (AP: +1.94 mm, ML: ±0.5 mm, DV: −3.3 mm) with a 20° angle, while 80 nl of rAAV-Ef1α-DIO-eNpHR3.0 -EYFP-WPRE-pA (BrainVTA, PT-0006) was injected into PrL (AP: +1.94 mm, ML: ±0.5 mm, DV: −2.1 mm), and optical fiber was also implanted in PrL (AP: +1.94 mm, ML: ±0.5 mm, DV: −1.9 mm). For inhibition of PrL-BLA projections, 100 nl of AAV9-eNpHR3.0-EYFP (BrainVTA, PT-0010) was bilaterally injected into PrL (AP: +1.94 mm, ML: ±0.5 mm, DV: −2.1 mm), and optical fiber was implanted into BLA (AP: −1.46 mm, ML: ±3.3 mm, DV: −4.4 mm).

Activity-dependent cell labeling

To label the engram cells, we crossed c-fos:tTA transgenic mice with TRE:H2B-GFP transgenic mice and subjected the double transgenic mice to AFC, or we injected AAV9-c-fos:tTA and AAV9-TRE-eNpHR3.0-EYFP or AAV9-TRE:ChR2-mCherry into WT mice for engram cell labeling. The double transgenic mice were maintained with the Dox-food condition (40 mg/kg) from their birth, and WT mice were treated with Dox-containing diet 2 weeks before surgery (7, 48). The mice were taken off Dox for 24 hours to open a window for fear memory engram labeling in context A. Then, the animals were exposed to context A for fear conditioning, and Dox diets were resumed immediately after AFC training.

Optogenetic manipulation of PrL and BLA engram cells

In this study, we tested whether the activation/inhibition of PrL and BLA engram cells labeled by ChR2–mCherry or eNpHR3.0-EYFP is sufficient or necessary for memory updating by optogenetic manipulation 30 min before extinction. A context distinct from the AFC training chamber (context B) was used, and all mice had patch cords fitted to the optic fiber implant before testing. For light-induced freezing behavior, ChR2 was stimulated at 4 Hz (15-ms pulse width) for PrL engram cells or at 20 Hz (15-ms pulse width) for BLA engram cells using a 473-nm laser (10 mW). The manipulation session was 200 s, and mouse received 20-s optical stimulation starting from 120 s. At the end of 200 s, the mouse was detached and returned to its home cage. In addition, eNpHR was stimulated for both PrL and BLA engram cells using a 589-nm laser (5 mW) during a retrieval trail; the laser was on during the tone onset and off at the end of tone. Following behavioral experiments, brain sections were prepared to confirm efficient viral labeling in target areas. Animals lacking adequate labeling were excluded before behavior quantification.

Calcium imaging surgery and data acquisition

Ca2+ imaging of PrL and BLA neurons was performed on WT mice. AAV5-hsyn-GCaMP6f (Tailtool, S02245) was injected into right PrL (AP: 1.94 mm, ML: +0.5 mm, DV: −2.15 mm) or BLA (AP: −1.46 mm, ML: +3.3 mm, DV: −4.68 mm), then a GRIN lens (0.5-mm diameter, 4.1-mm length; Inscopix) was implanted on PrL, and a GRIN lens (0.5-mm diameter, 6.1-mm length; Inscopix) was implanted on BLA after 2-week injection. Last, a baseplate (Inscopix) was attached above the GRIN lens by ultraviolet-light curable glue 2 weeks after GRIN lens implantation. The Ca2+ imaging data were captured (20 frames/s) using the Inscopix miniature microscope and nVista acquisition software (Inscopix, CA, USA) during retrieval, extinction, EM test, and SR test. In all the fear memory–related behavior experiments, a Transistor-Transistor-Logic (TTL) signal was used to synchronize the calcium signal and the behavioral time points.

Calcium imaging data processing and cell sorting

The processing of calcium imaging data and calcium signal extraction was accomplished by using the Inscopix Data Processing Software (IDPS, Inscopix) with the following steps. First, the raw videos were preprocessed by cropping it to a specified pixel region. Then, the images were then downsampled (×2) and filtered by using a spatial band-pass filter to remove low and high spatial frequency information (low cutoff: 0.005 pixel−1; high cutoff: 0.500 pixel−1). Next, each frame of the movies was estimated to minimize the difference between the transformed frame and the reference frame (blood vessels) using the rigid image registration algorithm for motion correction (49). After this step, each pixel value was normalized by ΔF(t) − F0/F0, where F0 is the mean value by averaging the signal of the entire video. Last, the spatial locations and calcium signals of individual cells were identified using the principal components analysis (PCA)/independent components analysis (ICA) algorithm (29). Ideally, each component was supposed to be one neuron, but it also identified some confounding components that may be nonneurons or nonbiological signals, so we manually removed those components by comparing their signal transients, locality, and morphology.

Identifying fear cells and extinction cells

To define the responsive cells, a Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed for the calcium signal of cells between the tone period and the equivalent no-tone period with a significance threshold of P < 0.05, according to a previous report (23). A cell was defined as fear cell if its signals during the tone period of retrieval were higher than those during the equivalent no-tone period with a significance threshold of P < 0.05, while cells whose signals during the last trail of the extinction period were higher than those during the equivalent no-tone period with the same threshold were defined as extinction cells, and US retrieval responsible cells were defined as the cells that show higher signal during the 20-s period from the US retrieval onset compared with signals during the 20-s period with no US. The reactivated fear cells or extinction cells in fig. S4 were defined as fear cells or extinction cells with the higher signals, which were examined during the tone period compared with signals during the no-tone period by the Wilcoxon rank sum test in different sessions. The reactivated fear cells or extinction cells during US retrieval in fig. S7 were defined as fear cells or extinction cells with the higher signals, which were tested during the 20-s period from the US onset compared with signals during the 20-s period with no US by the Wilcoxon rank sum test in US retrieval. The fear or extinction cell reactivation ratio in fig. S4 was calculated by reactivated fear cells/total fear cells or reactivated extinction cells/total extinction cells, while the reactivation level during US retrieval normalized to chance in fig. S7 was calculated by (reactivated fear cells/total cells)/[(fear cells/total cells) × (US retrieval responsible cells/total cells)]. The overlap of CS1 and CS2 fear cell was calculated by CS1 and CS2 co-responsible cells/total cells, while (CS1 fear cells/total cells) × (CS2 fear cells/total cells) was the chance level.

The distance between fear cells and extinction cells

To calculate the vector distance between fear cells and extinction cells, we performed the cosine distance calculation. The population vector x was defined as the normalized Ca2+ signal of fear cells in retrieval and population vector y was defined as the normalized Ca2+ signal of extinction cells in last trail of extinction. The cosine distance of two population vector x and y was calculated by the following formula

Statistics

GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to analyze the data with Student’s t test and one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. For single-factor experiments involving two or more than two groups, Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA was used. For experiments composed of multiple factors, a two-way ANOVA with test for interaction was used. All data were displayed as means ± SEM, and the significance was set at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

We thank Experimental Center, Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, and Translational Medicine Core Facility of Shandong University for consultation and instrument availability that supported this work.

Funding: This study was supported by the STI2030 Major Projects (2021ZD0202804), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32171029), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (no. ZR2020ZD17).

Author contributions: This study was conceptualized and designed by Z.-Y.C. and S.-W.T. S.-W.T. carried out the experiments and analyzed data. B.-W.D., J.-C.S., and G.-Z.F. contributed to transgenic mice keeping, histology, staining, and quantification. S.-Q.X. contributed to the behavioral experiment. S.-W.T., X.-R.W., X.-L.C., Y.-F.L., and G.-Z.F. processed and analyzed the calcium imaging data. The paper was written by Z.-Y.C. and S.-W.T.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S8

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Tanner M. K., Hake H. S., Bouchet C. A., Greenwood B. N., Running from fear: Exercise modulation of fear extinction. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 151, 28–34 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers K. M., Davis M., Mechanisms of fear extinction. Mol. Psychiatry 12, 120–150 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monfils M.-H., Cowansage K. K., Klann E., LeDoux J. E., Extinction-reconsolidation boundaries: Key to persistent attenuation of fear memories. Science 324, 951–955 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiller D., Monfils M.-H., Raio C. M., Johnson D. C., LeDoux J. E., Phelps E. A., Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms. Nature 463, 49–53 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J., Zhao L., Xue Y., Shi J., Suo L., Luo Y., Chai B., Yang C., Fang Q., Zhang Y., Bao Y., Pickens C. L., Lu L., An unconditioned stimulus retrieval extinction procedure to prevent the return of fear memory. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 895–901 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalaf O., Resch S., Dixsaut L., Gorden V., Glauser L., Graff J., Reactivation of recall-induced neurons contributes to remote fear memory attenuation. Science 360, 1239–1242 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura T., Ogawa S. K., Roy D. S., Okuyama T., Morrissey M. D., Smith L. M., Redondo R. L., Tonegawa S., Engrams and circuits crucial for systems consolidation of a memory. Science 356, 73–78 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramirez S., Liu X., Lin P. A., Suh J., Pignatelli M., Redondo R. L., Ryan T. J., Tonegawa S., Creating a false memory in the hippocampus. Science 341, 387–391 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lacagnina A. F., Brockway E. T., Crovetti C. R., Shue F., McCarty M. J., Sattler K. P., Lim S. C., Santos S. L., Denny C. A., Drew M. R., Distinct hippocampal engrams control extinction and relapse of fear memory. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 753–761 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herry C., Ciocchi S., Senn V., Demmou L., Muller C., Luthi A., Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature 454, 600–606 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senn V., Wolff S. B. E., Herry C., Grenier F., Ehrlich I., Grundemann J., Fadok J. P., Muller C., Letzkus J. J., Luthi A., Long-range connectivity defines behavioral specificity of amygdala neurons. Neuron 81, 428–437 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixsaut L., Graff J., The medial prefrontal cortex and fear memory: Dynamics, connectivity, and engrams. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12113 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergstrom H. C., The neurocircuitry of remote cued fear memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 409–417 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reijmers L. G., Perkins B. L., Matsuo N., Mayford M., Localization of a stable neural correlate of associative memory. Science 317, 1230–1233 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X., Ramirez S., Pang P. T., Puryear C. B., Govindarajan A., Deisseroth K., Tonegawa S., Optogenetic stimulation of a hippocampal engram activates fear memory recall. Nature 484, 381–385 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Do-Monte F. H., Quiñones-Laracuente K., Quirk G. J., A temporal shift in the circuits mediating retrieval of fear memory. Nature 519, 460–463 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maren S., Quirk G. J., Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 844–852 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu X., Wu Y. J., Zhang Z., Zhu J. J., Wu X. R., Wang Q., Yi X., Lin Z. J., Jiao Z. H., Xu M., Jiang Q., Li Y., Xu N. J., Zhu M. X., Wang L. Y., Jiang F., Xu T. L., Li W. G., Dynamic tripartite construct of interregional engram circuits underlies forgetting of extinction memory. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 4077–4091 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milad M. R., Quirk G. J., Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 420, 70–74 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters J., Dieppa-Perea L. M., Melendez L. M., Quirk G. J., Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science 328, 1288–1290 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xin J., Ma L., Zhang T. Y., Yu H., Wang Y., Kong L., Chen Z. Y., Involvement of BDNF signaling transmission from basolateral amygdala to infralimbic prefrontal cortex in conditioned taste aversion extinction. J. Neurosci. 34, 7302–7313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukherjee A., Caroni P., Infralimbic cortex is required for learning alternatives to prelimbic promoted associations through reciprocal connectivity. Nat. Commun. 9, 2727 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagihara K. M., Bukalo O., Zeller M., Aksoy-Aksel A., Karalis N., Limoges A., Rigg T., Campbell T., Mendez A., Weinholtz C., Mahn M., Zweifel L. S., Palmiter R. D., Ehrlich I., Luthi A., Holmes A., Intercalated amygdala clusters orchestrate a switch in fear state. Nature 594, 403–407 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank T., Monig N. R., Satou C., Higashijima S. I., Friedrich R. W., Associative conditioning remaps odor representations and modifies inhibition in a higher olfactory brain area. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 1844–1856 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka K. Z., Pevzner A., Hamidi A. B., Nakazawa Y., Graham J., Wiltgen B. J., Cortical representations are reinstated by the hippocampus during memory retrieval. Neuron 84, 347–354 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debiec J., Díaz-Mataix L., Bush D. E. A., Doyère V., Ledoux J. E., The amygdala encodes specific sensory features of an aversive reinforcer. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 536–537 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]