Abstract

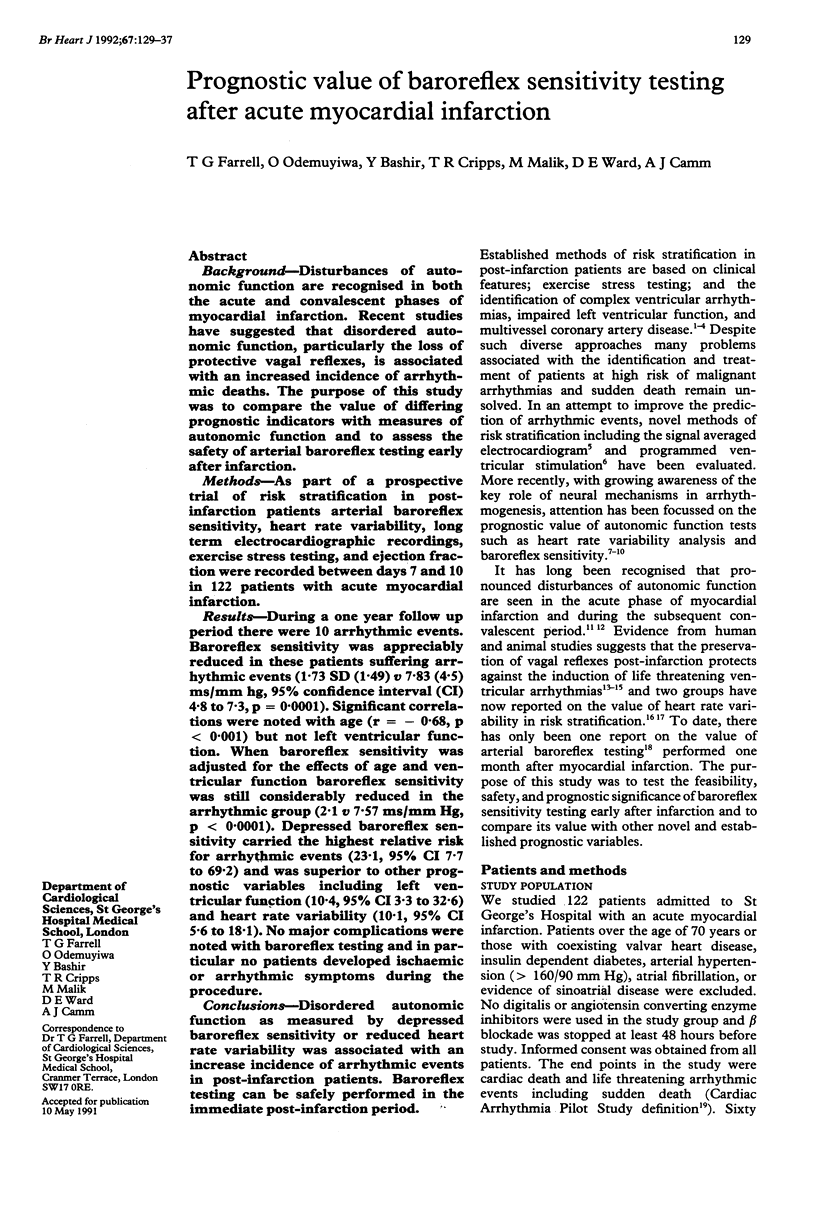

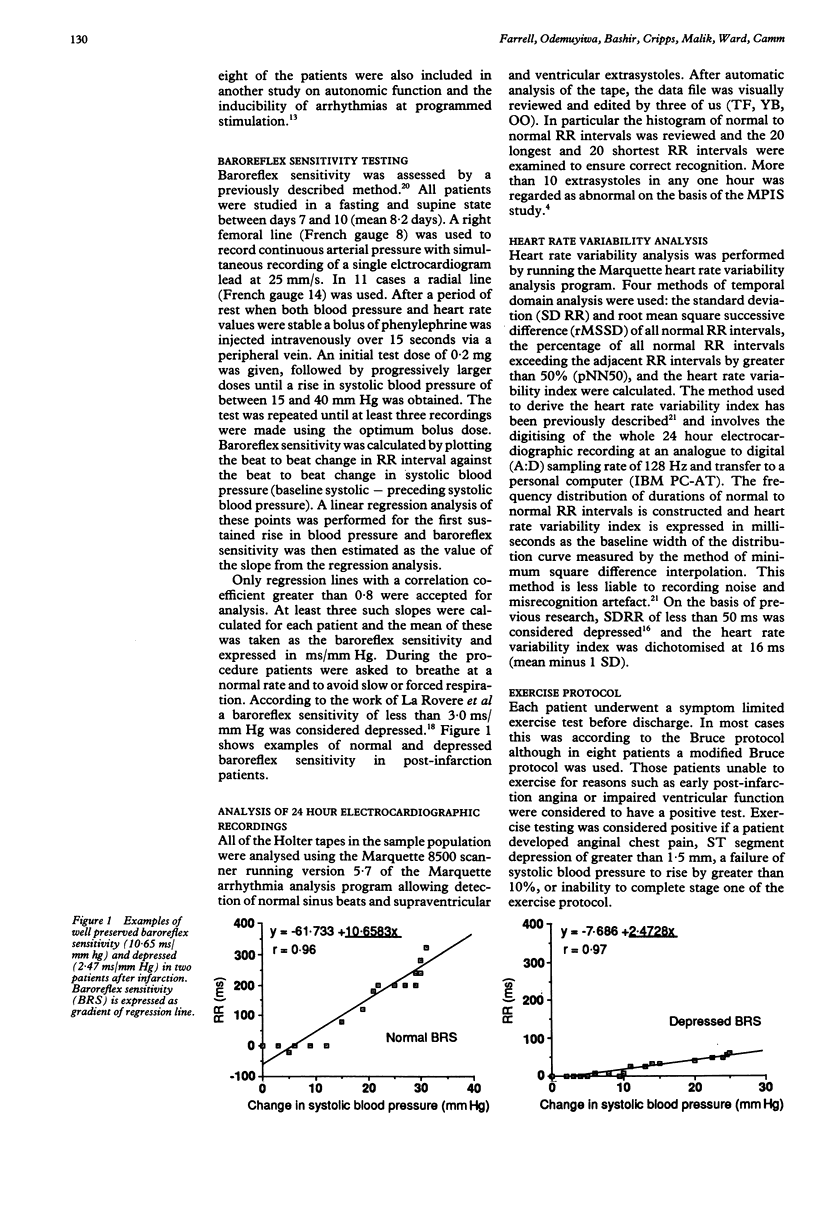

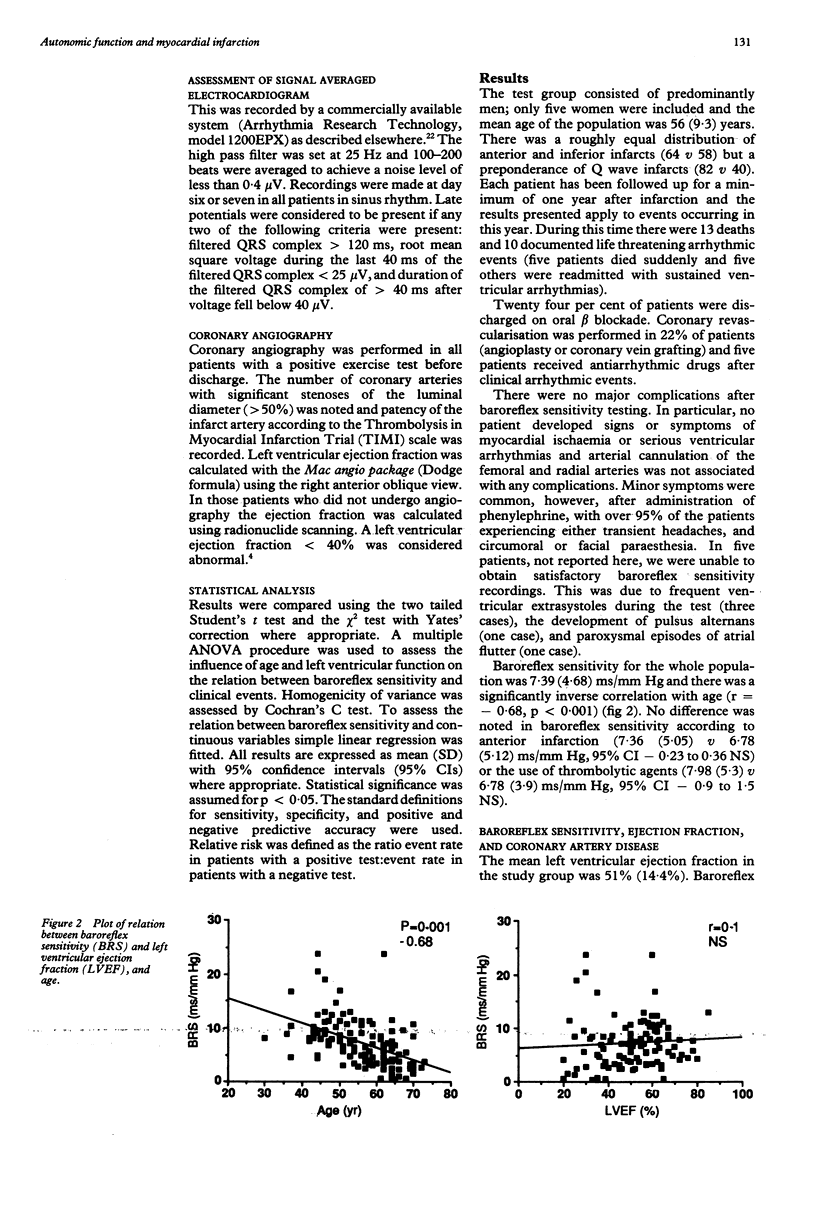

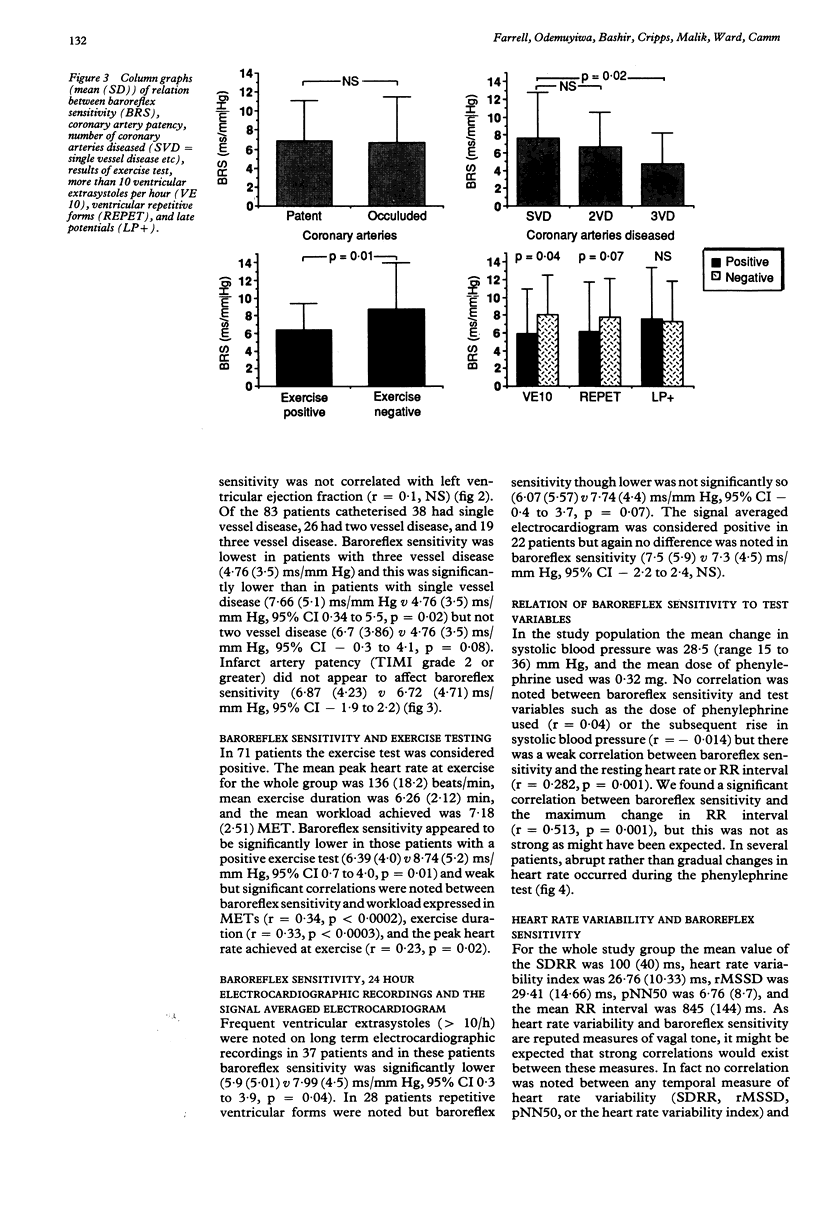

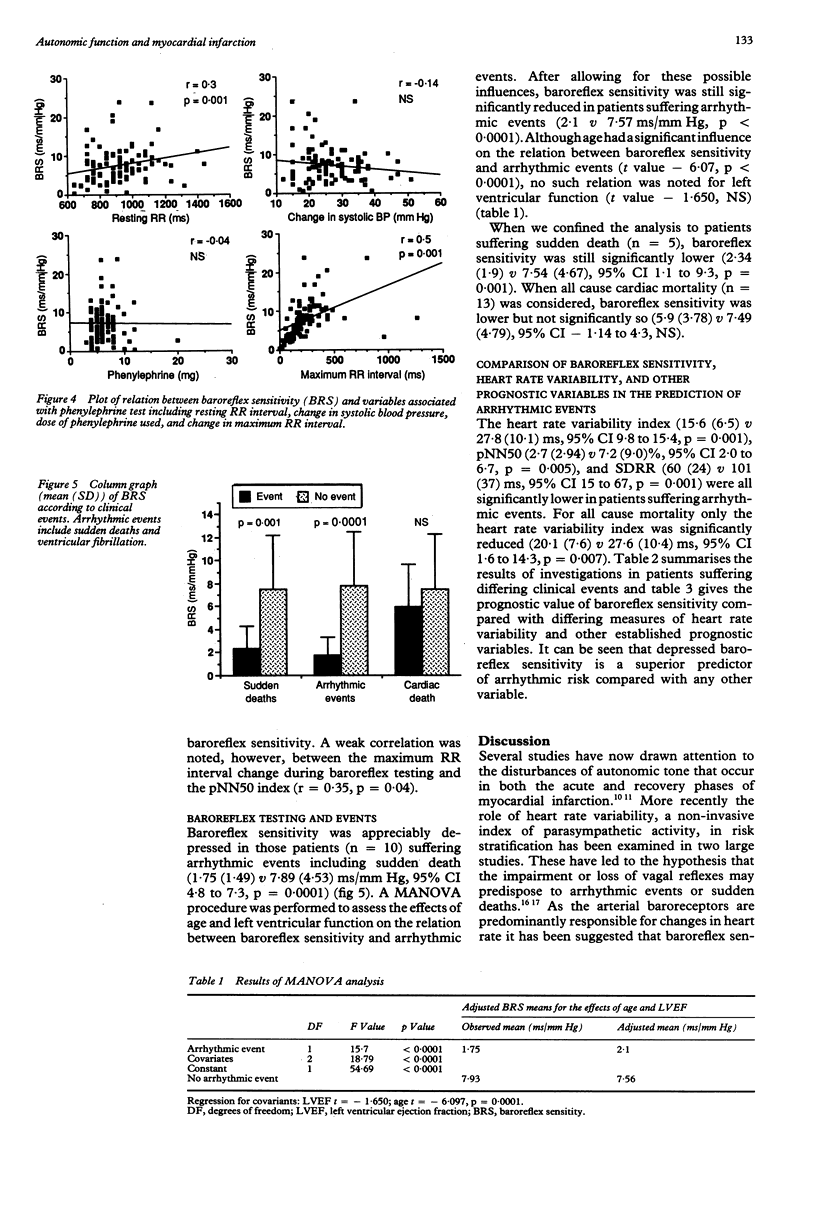

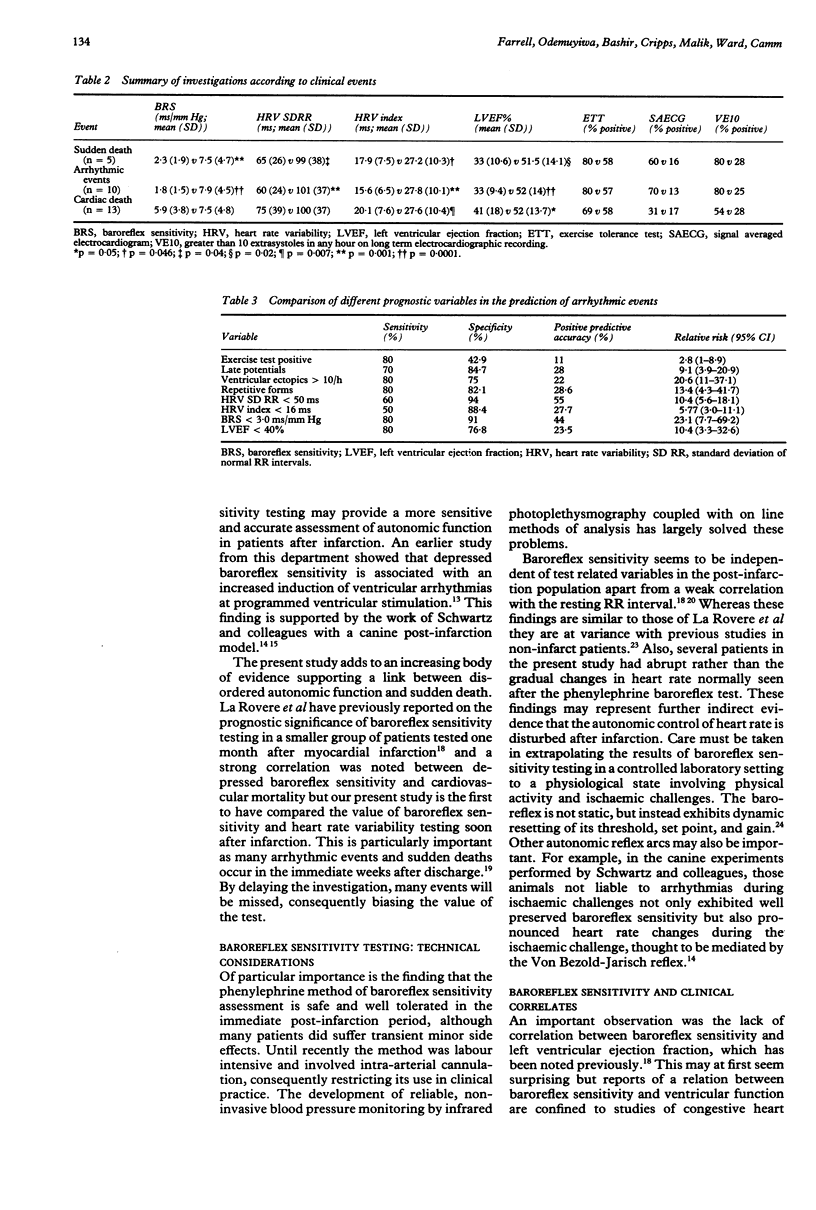

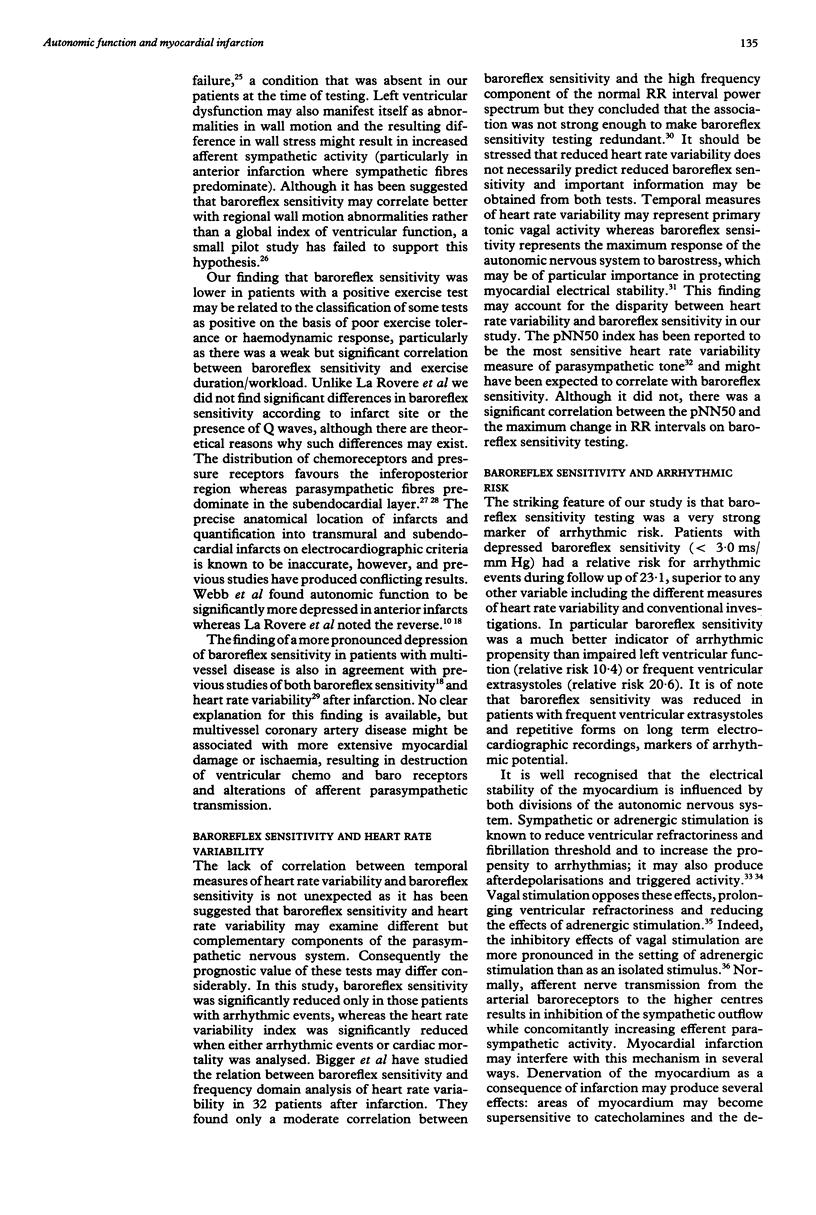

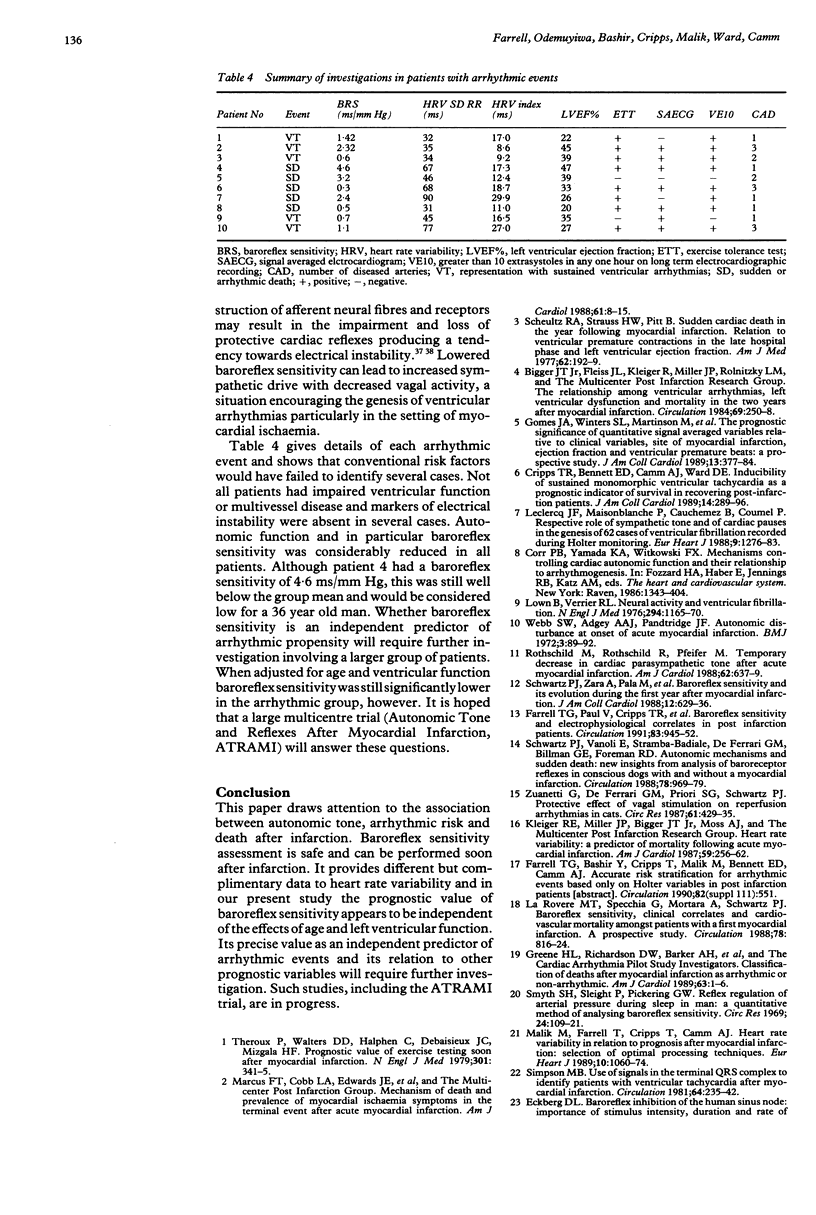

BACKGROUND--Disturbances of autonomic function are recognised in both the acute and convalescent phases of myocardial infarction. Recent studies have suggested that disordered autonomic function, particularly the loss of protective vagal reflexes, is associated with an increased incidence of arrhythmic deaths. The purpose of this study was to compare the value of differing prognostic indicators with measures of autonomic function and to assess the safety of arterial baroreflex testing early after infarction. METHODS--As part of a prospective trial of risk stratification in post-infarction patients arterial baroreflex sensitivity, heart rate variability, long term electrocardiographic recordings, exercise stress testing, and ejection fraction were recorded between days 7 and 10 in 122 patients with acute myocardial infarction. RESULTS--During a one year follow up period there were 10 arrhythmic events. Baroreflex sensitivity was appreciably reduced in these patients suffering arrhythmic events (1.73 SD (1.49) v 7.83 (4.5) ms/mm hg, 95% confidence interval (CI) 4.8 to 7.3, p = 0.0001). Significant correlations were noted with age (r = -0.68, p less than 0.001) but not left ventricular function. When baroreflex sensitivity was adjusted for the effects of age and ventricular function baroreflex sensitivity was still considerably reduced in the arrhythmic group (2.1 v 7.57 ms/mm Hg, p less than 0.0001). Depressed baroreflex sensitivity carried the highest relative risk for arrhythmic events (23.1, 95% CI 7.7 to 69.2) and was superior to other prognostic variables including left ventricular function (10.4, 95% CI 3.3 to 32.6) and heart rate variability (10.1, 95% CI 5.6 to 18.1). No major complications were noted with baroreflex testing and in particular no patients developed ischaemic or arrhythmic symptoms during the procedure. CONCLUSIONS--Disordered autonomic function as measured by depressed baroreflex sensitivity or reduced heart rate variability was associated with an increase incidence of arrhythmic events in post-infarction patients. Baroreflex testing can be safely performed in the immediate post-infarction period.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barber M. J., Mueller T. M., Davies B. G., Gill R. M., Zipes D. P. Interruption of sympathetic and vagal-mediated afferent responses by transmural myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1985 Sep;72(3):623–631. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corin W. J., Monrad E. S., Murakami T., Nonogi H., Hess O. M., Krayenbuehl H. P. The relationship of afterload to ejection performance in chronic mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 1987 Jul;76(1):59–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps T., Bennett E. D., Camm A. J., Ward D. E. Inducibility of sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia as a prognostic indicator in survivors of recent myocardial infarction: a prospective evaluation in relation to other prognostic variables. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989 Aug;14(2):289–296. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg D. L. Baroreflex inhibition of the human sinus node: importance of stimulus intensity, duration, and rate of pressure change. J Physiol. 1977 Aug;269(3):561–577. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckberg D. L., Drabinsky M., Braunwald E. Defective cardiac parasympathetic control in patients with heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1971 Oct 14;285(16):877–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197110142851602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing D. J., Neilson J. M., Travis P. New method for assessing cardiac parasympathetic activity using 24 hour electrocardiograms. Br Heart J. 1984 Oct;52(4):396–402. doi: 10.1136/hrt.52.4.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell T. G., Paul V., Cripps T. R., Malik M., Bennett E. D., Ward D., Camm A. J. Baroreflex sensitivity and electrophysiological correlates in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1991 Mar;83(3):945–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes J. A., Winters S. L., Martinson M., Machac J., Stewart D., Targonski A. The prognostic significance of quantitative signal-averaged variables relative to clinical variables, site of myocardial infarction, ejection fraction and ventricular premature beats: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989 Feb;13(2):377–384. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90515-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G. B., Thames M. D., Abboud F. M. Differential baroreflex control of heart rate and vascular resistance in rabbits. Relative role of carotid, aortic, and cardiopulmonary baroreceptors. Circ Res. 1982 Apr;50(4):554–565. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano J., Sakakibara Y., Yamada M., Ohte N., Fujinami T., Yokoyama K., Watanabe Y., Takata K. Decreased magnitude of heart rate spectral components in coronary artery disease. Its relation to angiographic severity. Circulation. 1990 Apr;81(4):1217–1224. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Zipes D. P. Results of sympathetic denervation in the canine heart: supersensitivity that may be arrhythmogenic. Circulation. 1987 Apr;75(4):877–887. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent K. M., Smith E. R., Redwood D. R., Epstein S. E. Electrical stability of acutely ischemic myocardium. Influences of heart rate and vagal stimulation. Circulation. 1973 Feb;47(2):291–298. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiger R. E., Miller J. P., Bigger J. T., Jr, Moss A. J. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Feb 1;59(4):256–262. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90795-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rovere M. T., Specchia G., Mortara A., Schwartz P. J. Baroreflex sensitivity, clinical correlates, and cardiovascular mortality among patients with a first myocardial infarction. A prospective study. Circulation. 1988 Oct;78(4):816–824. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.4.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leclercq J. F., Maisonblanche P., Cauchemez B., Coumel P. Respective role of sympathetic tone and of cardiac pauses in the genesis of 62 cases of ventricular fibrillation recorded during Holter monitoring. Eur Heart J. 1988 Dec;9(12):1276–1283. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy M. N. Sympathetic-parasympathetic interactions in the heart. Circ Res. 1971 Nov;29(5):437–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.29.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lown B., Verrier R. L. Neural activity and ventricular fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 1976 May 20;294(21):1165–1170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197605202942107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik M., Farrell T., Cripps T., Camm A. J. Heart rate variability in relation to prognosis after myocardial infarction: selection of optimal processing techniques. Eur Heart J. 1989 Dec;10(12):1060–1074. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus F. I., Cobb L. A., Edwards J. E., Kuller L., Moss A. J., Bigger J. T., Jr, Fleiss J. L., Rolnitzky L., Serokman R. Mechanism of death and prevalence of myocardial ischemic symptoms in the terminal event after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1988 Jan 1;61(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)91295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R. W., Pearlman A. S., Hyman R. M., Goldstein R. A., Kent K. M., Goldstein R. E., Epstein S. E. Beneficial effects of vagal stimulation and bradycardia during experimental acute myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 1974 May;49(5):943–947. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild M., Rothschild A., Pfeifer M. Temporary decrease in cardiac parasympathetic tone after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1988 Sep 15;62(9):637–639. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(88)90670-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze R. A., Jr, Strauss H. W., Pitt B. Sudden death in the year following myocardial infarction. Relation to ventricular premature contractions in the late hospitals phase and left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Med. 1977 Feb;62(2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P. J., Vanoli E., Stramba-Badiale M., De Ferrari G. M., Billman G. E., Foreman R. D. Autonomic mechanisms and sudden death. New insights from analysis of baroreceptor reflexes in conscious dogs with and without a myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1988 Oct;78(4):969–979. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.4.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P. J., Zaza A., Pala M., Locati E., Beria G., Zanchetti A. Baroreflex sensitivity and its evolution during the first year after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Sep;12(3):629–636. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(88)80048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simson M. B. Use of signals in the terminal QRS complex to identify patients with ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1981 Aug;64(2):235–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.64.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth H. S., Sleight P., Pickering G. W. Reflex regulation of arterial pressure during sleep in man. A quantitative method of assessing baroreflex sensitivity. Circ Res. 1969 Jan;24(1):109–121. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames M. D., Klopfenstein H. S., Abboud F. M., Mark A. L., Walker J. L. Preferential distribution of inhibitory cardiac receptors with vagal afferents to the inferoposterior wall of the left ventricle activated during coronary occlusion in the dog. Circ Res. 1978 Oct;43(4):512–519. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.4.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théroux P., Waters D. D., Halphen C., Debaisieux J. C., Mizgala H. F. Prognostic value of exercise testing soon after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1979 Aug 16;301(7):341–345. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197908163010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman M. B., Wald R. W. Termination of ventricular tachycardia by an increase in cardiac vagal drive. Circulation. 1977 Sep;56(3):385–391. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S. W., Adgey A. A., Pantridge J. F. Autonomic disturbance at onset of acute myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1972 Jul 8;3(5818):89–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5818.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuanetti G., De Ferrari G. M., Priori S. G., Schwartz P. J. Protective effect of vagal stimulation on reperfusion arrhythmias in cats. Circ Res. 1987 Sep;61(3):429–435. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]