Abstract

The study of Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) in preclinical models is hampered by difficulty in training rodents to voluntarily consume high levels of alcohol. The intermittency of alcohol access/exposure is well known to modulate alcohol consumption (e.g., alcohol deprivation effect, intermittent-access two-bottle-choice) and recently, intermittent access operant self-administration procedures have been used to produce more intense and binge-like self-administration of intravenous psychostimulant and opioid drugs. In the present study, we sought to systematically manipulate the intermittency of operant self-administered alcohol access to determine the feasibility of promoting more intensified, binge-like alcohol consumption. To this end, 24 male and 23 female NIH Heterogeneous Stock rats were trained to self-administer 10% w/v ethanol, before being split into three different-access groups. Short Access (ShA) rats continued receiving 30-minute training sessions, Long Access (LgA) rats received 16-hour sessions, and Intermittent Access (IntA) rats received 16-hour sessions, wherein the hourly alcohol-access periods were shortened over sessions, down to 2 min. IntA rats demonstrated an increasingly binge-like pattern of alcohol drinking in response to restriction of alcohol access, while ShA and LgA rats maintained stable intake. All groups were tested on orthogonal measures of alcohol-seeking and quinine-punished alcohol drinking. The IntA rats displayed the most punishment-resistant drinking. In a separate experiment, we replicated our main finding, that intermittent access promotes a more binge-like pattern of alcohol self-administration using 8 male and 8 female Wistar rats. In conclusion, intermittent access to self-administered alcohol promotes more intensified self-administration. This approach may be useful in developing preclinical models of binge-like alcohol consumption in AUD.

Keywords: Intermittent Access, Alcohol, Self-Administration, Operant, Reinforcement, Sex Differences

1. Introduction

Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) are among the most prevalent mental health disorders, affecting an estimated 14.5 million people in the US (National Institiute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; SAMHSA, 2019). Alcohol contributes to 18.5% of Emergency Department visits and is the third-leading cause of preventable death in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Mokdad et al., 2004; National Institiute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism). Alcohol misuse is estimated to have cost the United States $249 billion USD in 2010 (Sacks et al., 2015), including the cost estimated to arise from injury, death, legal fees, and lost productivity. AUD is characterized by an intensification in the pattern of alcohol consumption, the development of tolerance and withdrawal, and the persistence of alcohol consumption in the face of negative consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

A major contribution to the harmful effects of alcohol consumption is “binge drinking”. Historically, “binge drinking” was used by some clinicians to described a drinking pattern featuring periods of heavy-drinking that could last weeks (also referred to as “going on a bender”), and that were separated by stretches of alcohol abstinence. The modern and predominating usage of the term “binge drinking” is in attempting to describe in behavioral studies alcohol drinking episodes which result in “drunkenness” (Courtney & Polich, 2009; Lange & Voas, 2000). “Binge” alcohol drinking is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as achieving an 80 mg/dL blood alcohol concentration. This is intended to reflect the “5/4 definition” of binge-drinking, or the approximate blood alcohol concentration expected to result from an adult male consuming 5 standard drinks or an adult female consuming 4 standard drinks in approximately 2 hours (Fillmore & Jude, 2011; National Institue on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2022). Although not perfect, critical to the value of these definitions of binge drinking is the acknowledgement that the rate of alcohol consumption is key to evaluating the likely effects of alcohol consumption. For example, if an individual were to consume 7 standard drinks in a week, the rate at which these drinks are consumed could translate to very different drinking patterns with very different risks. If one glass of wine were consumed with dinner each night, this may never generate a state of drunkenness. This would be quite different from what we would expect if the same individual were to consume seven shots of liquor during Friday night happy hour.

As is the position of the World Health Organization, it can be argued that any level of alcohol consumption is not safe, given the health risks associated with even low amounts of alcohol and combined with the lack of consistent evidence to support any health benefit of alcohol consumption (Anderson et al., 2023; World Health Organization, 2023). Nevertheless, a focus on higher-rate alcohol consumption is well warranted, as it has been well established that binge drinking not only confers a greater likelihood of drunkenness, but also a higher likelihood of experiencing significant alcohol-related problems including vandalism, fights, injuries, drunk driving, trouble with police, and alcohol-related related health, social, economic, and/or legal consequences (Wechsler et al., 2000).

To develop treatments which can effectively reduce alcohol consumption in AUD, pre-clinical models are needed that capture, as best as is possible, unique aspects of the disorder. With the development of such pre-clinical models, we may identify and develop treatments with the best chance of translating findings from preclinical research to subpopulations of humans with AUDs (Venniro et al., 2020). A major hurdle to modelling AUD in rodents is that, generally speaking, there is a limit to how much alcohol that rats and mice will voluntarily consume. Various experimenter manipulations can be implemented to promote voluntary alcohol consumption. This may include the adulteration of alcohol liquid with a sweet tastant (Ji et al., 2008; Samson, 1986), fluid deprivation and/or making feeding contingent on alcohol consumption (Lieber & DeCarli, 1982; Rondeau et al., 1975), and chronic (months-long) alcohol access (Darbra et al., 2002; Schulteis et al., 1996). In our ongoing, collective effort to better model AUD, the length and frequency of access has also been manipulated by experimenters to increase alcohol consumption in various models of self-administration. This is a promising approach as it may be possible to implement without necessitating confounding variables associated with implementation of sucrose fading or food and/or fluid deprivation (Becker, 2000; Becker & Ron, 2014; Carnicella et al., 2014; Hopf & Lesscher, 2014; Tunstall et al., 2020). One example of a commonly used model is the intermittent 2-bottle choice model, where alcohol and water are offered in the homecage on a Mon-Wed-Fri schedule, which enhances the intensity of alcohol drinking during access periods when compared to animals with continuous two-bottle choice (Simms et al., 2008). Intermittent access (“every other day” access) has also been used to increase alcohol drinking in C57BL/J6 mice (Hwa et al., 2011; Melendez, 2011). Similarly, induction of enhanced alcohol self-administration during alcohol dependence is more effectively achieved by intermittent alcohol-vapor exposure compared to continuous exposure (O'Dell et al., 2004). Another example is the drinking-in-the-dark model, which limits drinking of C57BL/6J mice to the early component of the dark period of the light:dark cycle (Rhodes et al., 2005). This model has since been adapted for use in rats (Holgate et al., 2017; Zallar et al., 2019).

Despite progress made in developing rodent models of AUD, rodents do not readily display high levels of operant lever pressing for alcohol as is the case with intravenous self-administration of psychostimulant and opioid drugs (i.e., expected to induce moderate-severe intoxication). Using a behavioral economic framework , it is clear that in addition to consumption, the willingness to defend that consumption (i.e., the “demand” for alcohol), also appears weak relative to other drugs or non-drug reinforcers (Kearns et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Kim & Kearns, 2019; McConnell et al., 2021; Schwartz et al., 2017). Making the problem more challenging, it appears that a history of intermittent 2-bottle choice homecage drinking does not necessarily transfer to enhanced consumption or demand for alcohol during operant self-administration (Kim & Kearns, 2019). In brief; there remains a need for procedures that model more intense alcohol consumption in rodents, particularly in the context of operant self-administration, which allows more flexibility and nuance in assessing motivation for alcohol.

Recent experiments demonstrated that intermittent access (IntA) intravenous cocaine self-administration in the operant chamber can produce intensified, binge-like self-administration and increased motivation for cocaine compared to continuous access regimens (Algallal et al., 2020; Allain et al., 2018; Allain et al., 2015; Allain & Samaha, 2019; James et al., 2019; Kawa et al., 2016; Kawa & Robinson, 2019; Zimmer et al., 2011; Zimmer et al., 2012). In this model, brief periods of access to self-administration, typically 5 min, are followed by periods of non-access, typically 25 min, over the course of a session lasting several hours. Since the publication of the original report (Zimmer et al., 2012), the general effect has been replicated and extended to demonstrate that intermittent access relative to continuous access schedules produced increased escalation of cocaine intake (Kawa et al., 2016) and incubation of cocaine seeking (Nicolas et al., 2019). Further, it has been argued that the binge-like patterns of drug taking produced by intermittent-access schedules more closely match the patterns of cocaine self-administration that occur in SUD (Allain & Samaha, 2019). More recently, the binge-like effect of IntA training has been observed with intravenous opioids (D'Ottavio et al., 2021; Fragale et al., 2021) and intravenous nicotine (Tapia et al., 2022). Based on this rapidly developing area of research, we hypothesized that intermittent access to operantly self-administered ethanol could enhance binge-like consumption of alcohol and promote more addiction-like alcohol drinking in orthogonal measures of motivation for alcohol. At this time, we are not aware of any published report which is designed to directly assess the utility of adapting the intermittent access model for the assessment of operant alcohol self-administration in rodents.

In order to determine whether intermittent access to operant alcohol self-administration could produce a more intensified and binge-like pattern of self-administration, male and female rats were trained in daily operant sessions to press one lever to receive 0.1 ml of 10% w/v ethanol and another lever to receive water (0.1 ml). Rats were then split into groups matched in terms of alcohol consumption and allowed short access (ShA; 30 min), long access (LgA; 16h), or intermittent access (IntA; 16h, with one limited-access period per hour, interspersed with non-access periods). Rats were tested for alcohol seeking in acute (day 1) and protracted (day 21) alcohol abstinence, for re-acquisition of alcohol self-administration (post-day-21), and for punishment-resistant alcohol drinking (quinine adulteration). These tests were completed to determine the extent to which any effects induced by intermittent-access training conferred an intensification of alcohol-motivated behavior in orthogonal measures of alcohol-seeking behavior and alcohol-drinking-despite-punishment. Given that previous studies have manipulated the intermittency of homecage alcohol access or alcohol vapor exposure to promote alcohol consumption, and given the binge-like drug intake reported during intermittent access to operant self-administration of drugs from other drug classes, we hypothesized that rats trained on intermittent access to operant alcohol self-administration would demonstrate an intensified, more binge-like pattern of alcohol drinking when compared to their continuous access counterparts (i.e., LgA condition) and that they would exhibit more alcohol-seeking behavior and more punishment-resistant alcohol drinking.

As the ultimate goal of our experiments is translating findings to humans, we employ the NIH Heterogeneous Stock rat, that was initially developed by crossing 8 disparate inbred strains and which harbors approximately 10 million genetic variants (compared to about 90 million in humans) (Hansen & Spuhler, 1984). The use of such a genetically diverse population has several advantages, for example, variants controlling alcohol behavior have normal distributions in the population, unlike inbred strains where variants are binary (either present or absent) or in smaller outbred populations, such as the Wistar or Long Evans, where breeding history has eliminated the contribution of many genetic variants (Hansen & Spuhler, 1984). The rat was originally developed at the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism for the study of alcohol-related traits (Spuhler & Deitrich, 1984), and our present work aims to extend the alcohol-related behavior studied in the heterogeneous stock rat to include operant intermittent access alcohol self-administration. We increased the number of subjects used and length of training typically employed in our alcohol self-administration with Wistar rats (e.g., Tunstall et al., 2019), in order to account for the genetic diversity of the NIH Heterogeneous Stock rat and anticipated resulting behavioral diversity. In addition, we conducted a generalized replication experiment using a smaller cohort of Wistar rat (8 male, 8 female), in order to demonstrate that the effect of intermittent access on alcohol self-administration could be similarly generated in a strain of rat which has been more commonly used in alcohol research. We included a circadian cue-light in this experiment, to test the novel hypothesis that male and female operant behavior would differently be regulated by circadian factors, and further, that IntA might break down circadian control of behavior, as alcohol access periods come to dictate the periodicity of behavioral activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and Housing

47 NIH Heterogeneous Stock Rats bred at University of Tennessee Health Science Center were used in the experiment (24 males and 23 females; one additional male rat began the experiment but was excluded after failing to acquire lever pressing during the initial 13 sessions, and as such this rats’ data is not included in any of the raw data files, analyses, or figures of the manuscript). Rats were group-housed in NexGen Rat900 cages (Allentown, PA) lined with corn cob bedding (Maumee, Ohio). Rats were given ad libitum access to water and food while in the home cage and housed on a 12:12 reversed light:dark cycle (lights on 6pm, off 6am). The colony room was held at approximately 21 degrees Celsius and 31% humidity. All behavioral studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center and all procedures were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition (2011).

2.2. Operant Chambers

32 Med-Associates operant chambers (ENV-009X) were enclosed within sound attenuation chambers equipped with a ventilation fan. Each chamber measured 30 × 24 × 24 cm and had aluminum front and rear walls with clear polycarbonate side walls. The front wall of each chamber had two non-retractable levers located on either side of a magazine containing a dual-cup receptacle. A Med-Associates light array (ENV-222Q) was located above each lever. A 28-volt DC relay was mounted to the top of the operant chamber. When pulsed at 4 Hz, this relay created an approximately 75-dB click stimulus. Each cup within the dual-cup receptacle was attached to a 35ml syringe set within a 5 RPM syringe pump (PHM-100 and PHM-200). All syringe pumps were calibrated and set to deliver 0.1 ml of liquid. Med-PC Software was utilized to control the operant chambers and to record responses. Food was available in chambers during all 16-h overnight sessions.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Lever Press Acquisition

All rats were first trained to acquire lever pressing for alcohol before being assigned to groups. Prior to the first operant training session, all rats were given overnight access to a bottle of 10% w/v alcohol concurrent with a bottle of water in their home cage to allow taste habituation. During acquisition of leverpress responding, operant sessions were conducted once daily, 5 days a week, and the green LEDs above both levers were illuminated to serve as the houselight, indicating that the levers were active. During these sessions, rats could press one of two levers to receive 0.1 ml of 10% w/v ethanol in water and press the other lever to receive 0.1ml of water. Liquid reinforcers were delivered over 1.4-s infusions into separate wells within the drinking magazine. Reinforcer deliveries were indicated by extinguishing the green houselight LEDs and illuminating the yellow LED above the lever pressed. At the end of each delivery the yellow LED was extinguished, and the green houselight LEDs were illuminated again. To train the leverpress response, rats were first trained on 16-h sessions until each rat made 100 total presses combined across levers. Then, rats received a single 2-h operant session and a single 1-h session (unless rats did not make 10 total presses combined across levers, in which case the 1-h session was repeated). Once meeting the training criteria, rats began 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions. Because of the genetic variability between NIH Heterogeneous Stock Rats (Hansen & Spuhler, 1984; Woods & Mott, 2017), we ran a total of 46, daily 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions in order to demonstrate clearly that alcohol served as a reinforcer (i.e., by establishing lever pressing for alcohol consistently higher than the level of lever pressing for water), and, to ensure the development of a stable pattern of consumption before splitting rats into different-access groups matched in terms of their baseline alcohol consumption. The decision about when this goal was reached was based on inspection of both group mean and variance as well as individual lever press data (see Supplemental Material for all individual-level data).

2.3.2. IntA/LgA/ShA Training

After lever press acquisition was complete, rats were assigned to either the IntA, LgA, or ShA groups. The three groups were matched based on their average g/kg of alcohol over their last 8 sessions of acquisition. All groups received operant training sessions once daily, 5 days a week. The IntA group (n = 15, 8 males and 7 females) had 16-h sessions, with the availability of alcohol and water during the session gradually reduced over sessions in this phase. For the first three 16-h sessions, both IntA and LgA groups had continuous access to alcohol and water. Then IntA rats received one session with access to alcohol and water only during the first 40 min of each hour, one session with access only during the first 20 min of each hour, nine sessions with access only for the first 10 min of each hour, six sessions with access only during the first 5 min of each hour, and 12 sessions with access only during the first 2 min of each hour. Access was gradually reduced in this way as we monitored the performance of IntA rats (i.e., response rate during access periods, number of access periods with responses, and discrimination ratio [response rate during access periods as a function of response rate during non-access]) and adjusted the progressive shortening of access-periods accordingly. Meanwhile, the LgA group (n=16 rats, 8 males and 8 females) continued to receive 16-h sessions throughout this phase, during which they had continuous access to alcohol and water. Again, food was available in chambers during all 16-h overnight sessions. The ShA group (n=16, 8 males and 8 females) continued to receive sessions lasting 30 min during this phase and could lever press for alcohol and water throughout the 30-min sessions (i.e., the session parameters matched those used during the acquisition phase).

For all groups, illumination of the green LEDs above the levers signaled availability of alcohol and water. This meant that for the LgA and ShA groups, the green LED lights above the levers were illuminated throughout the session, except during the 1.4-s fluid delivery periods. For the IntA group, green houselight LEDs were illuminated to signaled alcohol and water availability during intermittent access periods. During this phase, the click stimulus was presented to all groups for 2 min at the start of each session and for 2 min at the top of each subsequent hour of the session in the IntA and LgA groups (ShA sessions lasted only 30 min). This was intended to match groups in terms of click exposure, while alerting rats in the IntA group to the start of access periods because there was a concern that LED illumination might not be salient enough.

2.3.3. Cue-Motivated Alcohol-Seeking Test

Following the last IntA, LgA, or ShA session, rats in all three groups underwent the same 1h cue-motivated alcohol-seeking test under extinction conditions. For this one-hour test, the click stimulus was presented for the entirety of the test. Additionally, under the extinction conditions, presses on either lever resulted in the same cues as their previous sessions; the extinguishing of the green LED house lights and the illumination of the yellow cue lights but no einforcer was given for the duration of the hour. After this first test, all rats were left in their homecages until day 21 when the test was repeated.

2.3.4. Test of Punished Alcohol Drinking

Following the seeking tests, each group was given five reacquisition sessions to retrain on their respective access schedule (i.e., IntA, LgA, or ShA). After completing reacquisition training, rats were tested for the persistence of punished alcohol drinking. This was accomplished by adding quinine to the alcohol solution, beginning with a 6th reacquisition session, used to establish a “0%” baseline of consumption. Doses of quinine were increased over successive sessions according to the following sequence: 0.003, 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, and 0.3g/L (adapted from (Hopf et al., 2010; Hopf & Lesscher, 2014)). The rats were trained with the quinine-adulterated alcohol on the same IntA, LgA, or ShA procedure that they were trained on previously.

2.3.4. Generalized Replication of Different-Access Training Effect on Alcohol Self-Administration in Wistar rats

Wistar rats (8 male, 8 female) were first trained to self-administer alcohol (see section 2.3.1) and all rats were allowed 10, 30-min sessions to self-administer alcohol before being split into two groups matched in terms of alcohol consumption (8 intermittent access “IntA” and 8 continuous access “ContA” rats, each group comprised of 4 males and 4 females). Next the IntA rats received 10 sessions of intermittent-access training (similar to the IntA group in the previous experiment) while the ContA rats received 10 sessions of continuous access training (similar to the LgA group in previous experiment). There were several differences between the prior experiment in NIH Heterogeneous Stock rats and the present experiment in Wistar rats that make this a generalized replication (i.e., replication with different experimental features, which should not impact the ability to replicate the finding of interest). Notably: Wistar rats were trained in standard Med-Associates boxes which were fitted with retractable levers; insertion of the retractable lever was used to signal and make available alcohol in the IntA group with no auditory cue used to signal alcohol availability in the experiment (note: a retractable lever was also inserted in parallel with the alcohol lever, and delivered water if pressed); the Wistar rats received 5-min access per hour from the first session of different-access training and this was maintained through all 10 sessions of different-access training; in order to study the possibility of circadian control of behavior and it’s different impact upon the behavior of male and female rats, the Wistar rats did not receive a houselight cue to signal when the session was active, but instead received a “circadian cue light”. This cue light was a houselight that was illuminated during the middle 12 h of the 16-h session and thereby mimicked the light phase of these 12:12 reverse light:dark rats housing conditions (we were not concerned that rats would be confused, as insertion of the retractable lever could serve as the signal for availability of self-administered alcohol). This allowed us to determine changes in drinking observed in the 2-h pre-/post- the circadian cue turning on (first 4-h of session) and turning off (final 4-h of session). The purpose of this experiment was to demonstrate that the effect of intermittent access on alcohol self-administration could be similarly generated in the Wistar strain of rat which has been more commonly used in alcohol research, even under conditions which are not identical to those used in the experiment with the NIH Heterogeneous Stock rat (i.e., it was not our intention to make direct comparisons between the behavior of these strains of rats).

2.3.5. Data and Statistics

Data was organized using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Excel Version 2202) and analyzed and plotted in Prism (GraphPad Prism 9). Lever pressing was converted to g/kg to account for differences in bodyweight of male and female rats. To analyze and visualize the response patterns of the three different-access groups, g/kg/h of access was used to account for the differences in length of access between groups and to account for the decreasing length of access periods within the IntA group across sessions. To calculate the g/kg/h of access, each rat’s access pressing was converted into grams of ethanol then divided by their weight. The g/kg of alcohol consumed was then divided by the number of hours of access.

Statistical analysis was completed using 3-Way and 2-Way Repeated or Mixed Measures ANOVA within GraphPad Prism 9. Between-subjects variables consisted of Group and Sex, while Session and Lever were within-subject variables. Rates of responding were quite different between the different-access groups, and/or, quite different within specific groups as their behavior changed drastically across the training/testing sessions. As a result, the variance was quite different between levels of factors in analyses which included Group as a factor. To help account for this, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used for such ANOVAs (i.e., analysis of data shown in Figs. 3, 5C, and 6A). For all ANOVAs, post-hoc testing was completed with Holm-Sidak tests where appropriate. To assess the correlation between unpunished and punished alcohol drinking (Figs. 6B-D), we selected the two highest concentrations of quinine in our cumulative concentration-response curve as, congruent with the literature, our rats tended to plateau in quinine-suppression of alcohol drinking at these quinine concentrations (Hopf et al., 2010; Hopf & Lesscher, 2014). Several of our rats consumed slightly more alcohol at the 0.3mg/L vs. 0.1mg/L quinine concentration, and so to best represent “punished alcohol drinking” we averaged the 0.1mg/dL and 0.3 mg/dL consumption for all rats, and then averaged the last two sessions before quinine adulteration began to generate a baseline comparator point sourced from a matched sized data sample. The self-administration behavior of Wistar rats and the effect of circadian phase on Wistar rat self-administration behavior (Figs 7 & 8) were analyzed using the appropriate ANOVA followed by Hom-Sidak post-hoc testing where required, using the same metrics as described for the analysis of NIH Heterogeneous Stock rat behavior.

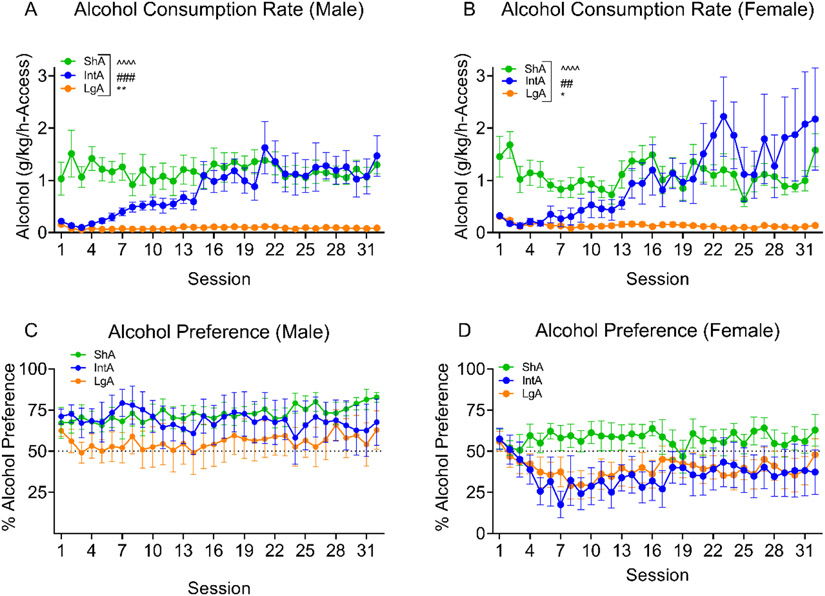

Figure 3.

The rate of alcohol consumption for the three groups across 32 different-access sessions A. The ShA and LgA males maintained relatively stable consumption across sessions of different-access sessions, while the IntA males increased their rate of consumption across sessions, as the length of alcohol access was reduced. B. Similarly, the females ShA and LgA rats maintained relatively stable consumption across sessions. The IntA females drastically increased their rate of consumption across sessions of shortening alcohol access. C. Alcohol preference in males was not significantly different across sessions or between the three groups. D. In females, no significant difference in alcohol preference was observed across sessions or between groups. **p<0.01, *p<0.05 main effect of Session; ###p<0.01, ##p<0.001 main effect of Group; ^^^^p<0.0001 Session x Group interaction.

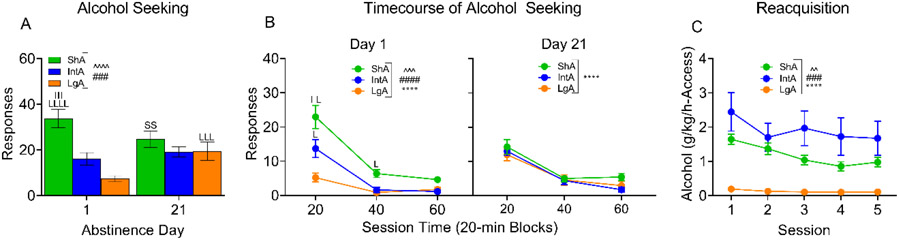

Figure 5.

Alcohol-seeking following different-access training. A. The alcohol-seeking test responses of each group are shown. The ShA responded more than both the IntA and LgA on day 1 and there were no differences on day 21 after the ShA responding decreased and the LgA responding increased. B. The two seeking tests were broken into 20-min blocks. On day 1 all three groups were different at the first 20-min, but then decreased responding across the last 40-min until they were no longer different. No group differences were seen on day 21, however responding differed between the three 20-min blocks. C. 5 sessions of reacquisition of alcohol self-administration following alcohol-seeking tests are shown. IntA had the highest alcohol consumption during reacquisition, followed by ShA, and then LgA. Differences in consumption across the 5 sessions are likely due to low responding by the IntA on session 2. ****p<0.0001 main effect of Session; ####p<0.0001, ###p<0.001 main effect of Group; ^^^^p<0.0001, ^^^p<0.001, ^^p<0.01 Session x Group interaction. S, L, and I are used to indicate difference from ShA, LgA, and IntA respectively, including when these groups differed from themselves between test days.

Figure 6.

Punished (quinine-adulterated) alcohol drinking following reacquisition of alcohol self-administration. A. Alcohol consumption at baseline and across increasing concentrations of quinine is shown for the three access groups. IntA had the highest rate of consumption, followed by ShA, and then LgA. The ShA and LgA significantly decreased their alcohol consumption at 0.03g/L quinine, while the IntA were the most persistent, less affected by the adulteration with quinine. B. The correlation between the ShA unpunished (average of reacquisition and 0g/L dose) and punished (average of 0.1 g/L and 0.3 g/L) alcohol consumption is shown. The black line illustrates the line of perfect correlation (i.e., y=x; the relationship expected if imposition of punishment has no effect). The punished and unpunished drinking are not significantly correlated in the ShA condition, and their data produce the shallowest slope of the three groups, meaning that the ShA demonstrate the least persistence during quinine adulteration. C. The IntA unpunished (average of reacquisition and 0g/L dose) and punished (average of 0.1 g/L and 0.3 g/L) alcohol consumption is highly correlated, exhibiting a steep slope near to the black line, indicating modest suppression during quinine adulteration. D. The significant, medium correlation between the LgA (average of reacquisition and 0g/L dose) unpunished versus punished (average of 0.1 g/L and 0.3 g/L) alcohol consumption exhibits a moderate slope, indicating that the LgA did display suppression during quinine-adulteration but not to the same extent observed in ShA rats. ****p<0.0001 main effect of Session; ###p<0.001 main effect of Group; ^p<0.05 Session x Group interaction; ***p<0.001, **p<0.01; *p<0.05, above individual datapoints, indicate different compared to session 1.

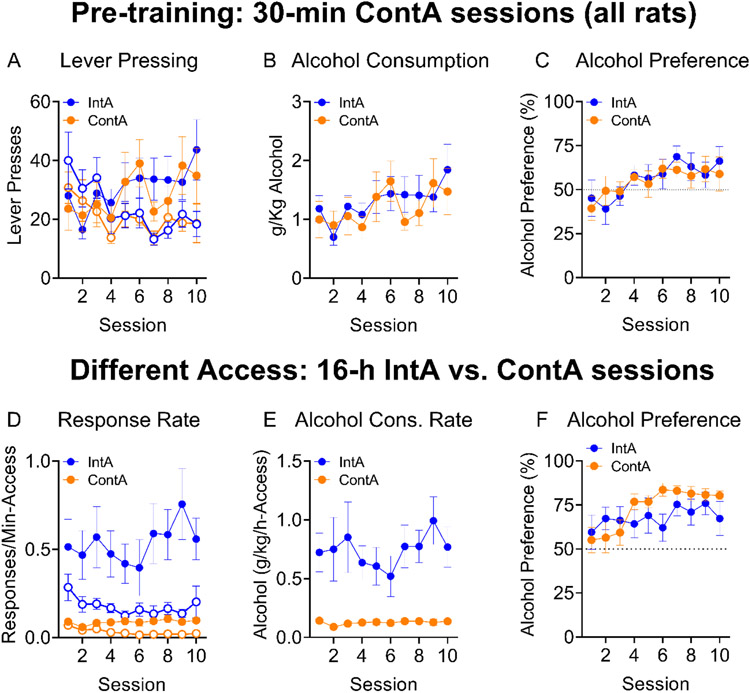

Figure 7.

Generalized replication of intermittent-access effect on rate of alcohol consumption in Wistar rat. Figs. 7A-C show the behavior of the to-be-split groups during their initial training where all rats received 10 sessions of the same 30-min self-administration training. both to-be-split groups responded more on the alcohol lever than the water lever over sessions (7A). Alcohol consumption (7B) and preference (7C) increased significantly over these 10 training sessions. In the next phase, where IntA rats received 5 min of alcohol access per hour. We observed that across this phase, both groups responded more for alcohol than water and that the IntA group responded at a higher rate than the ContA rats, (Fig 7D). The IntA Wistar rats displayed a much higher rate of alcohol consumption compared to ContA Wistar rats across this phase (Fig. 7E). Finally, preference for alcohol increased across this phase in both groups, with a significant interaction indicating some individual-session differences with groups converging by the end of the phase to a similar alcohol preference (Fig 7F).

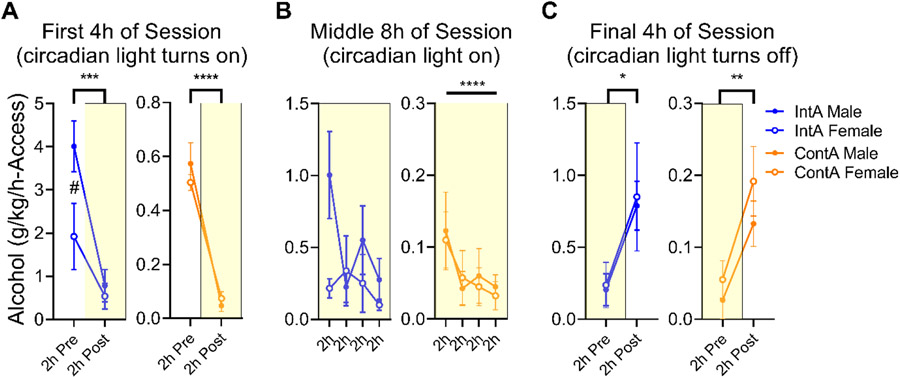

Figure 8.

Circadian control of drinking behavior in male and female Wistar rats trained on intermittent- and continuous-access schedules. Circadian control of drinking continued to be a relevant factor in the behavior of both male and female, IntA and ContA rats. For the “light turns on” period (first 4h; Fig. 8A), for the “light turns off” period (final 4h; Fig 8C). In analyzing the middle 8h portion of the session, we noted that ContA but not IntA decreased consumption across time, in line with the maintenance of a higher rate of alcohol consumption in IntA rats (Fig 8B). The only place we observed sex differences in this analysis was in IntA male vs. IntA female rats in the first 2-h of the session (Fig 8A), suggesting a possible enhanced frontloading of alcohol behavior in male rats specifically during IntA training. ****p<0.0001,***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 indicate main effect; # indicates group difference at indicated timepoint.

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of Operant Alcohol Self-Administration

During initial lever press acquisition, all rats met the overnight training criterion within 5 sessions (1.5 ± 0.13). Following the single 2h session, all rats met the 1h session criterion within 4 sessions (1.08 ± 0.06). Supplemental Figure S1 shows alcohol and water pressing for the final overnight, 2h, and 1h sessions plotted by sex. Pressing on the overnight and 2h sessions did not differ by sex, though the males pressed more than the females on both levers during the final 1h session.

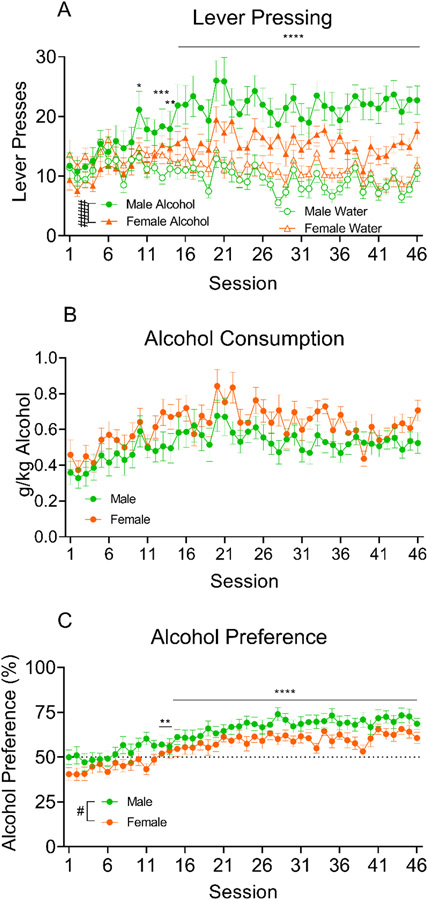

Across the 46, 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions, an increase in pressing was observed (Fig. 1A). Collapsed across Sex, alcohol presses increased across sessions and held at a significantly higher level than water presses after session 13 (Session: F (13.50, 621.0) = 4.974, p<0.0001; Lever: F (1.000, 46.00) = 21.46, p<0.0001; Session x Lever: F (12.72, 585.2) = 11.14, p<0.0001; Session 10: p=0.0234, Session 13: p=0.0001, Session 14: p=0.0024, Session 15-46: p<0.0001). Additionally, when the data were analyzed split by Sex, it was confirmed that males increased their alcohol -but not water- pressing to a significantly higher level than females (Sex: F (1, 45) = 2.613, p=0.1130; Lever: F (1, 45) = 24.17, p<0.0001; Sex x Lever: F (1, 45) = 8.255, p=0.0062).

Figure 1.

Responses on the alcohol and water lever for all rats initial 48, 30-minute alcohol self-administration sessions. A. Alcohol and water lever presses for males and females are plotted along 46, 30-minute training sessions. Alcohol presses (collapsed across Sex) increased across sessions and remained significantly elevated compared to water presses from session 13 onward. Additional analysis (split by Sex) confirmed that males increased their alcohol -but not water-pressing to a significantly higher level than females. B. No difference in alcohol consumption was seen after accounting for difference in bodyweight between males and females. C. Males displayed a greater alcohol preference than females, although alcohol preference increased for all rats across sessions (significantly increased relative to session 1 from session 13 onward). ####p<0.0001, #p=0.05 main effect of Group; ****p<0.0001, ***p=0.001, **p=0.01, *p=0.05 different from session 1.

Figure 1B shows the g/kg of alcohol consumed across 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions. The 2-way ANOVA showed that all rats increased their alcohol consumption across sessions, and no difference between males and females in terms of alcohol consumption was observed after accounting for differences in their bodyweight (Session: F (45, 2025) = 5.000, p<0.0001; Sex: F (1, 45) = 2.763, p=0.1034; Session x Sex: F (45, 2025) = 0.8946, p=0.6716).

Due to potential differences in total fluid intake between males and females, alcohol preference was also plotted (Fig. 1C). Both males and females increased alcohol preference across sessions, with males maintaining a higher preference than females (Session: F (12.54, 564.1) = 14.72, p<0.0001; Sex: F (1, 45) = 4.483, p=0.0398; Session x Sex: F (45, 2025) = 0.7962, p=0.8321). This is likely the result of higher water intake in female rats during these sessions, and male and female water intake (ml/kg) during 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions is shown in Supplemental Figure S2.

3.2. Different-access training: ShA, LgA, and IntA groups

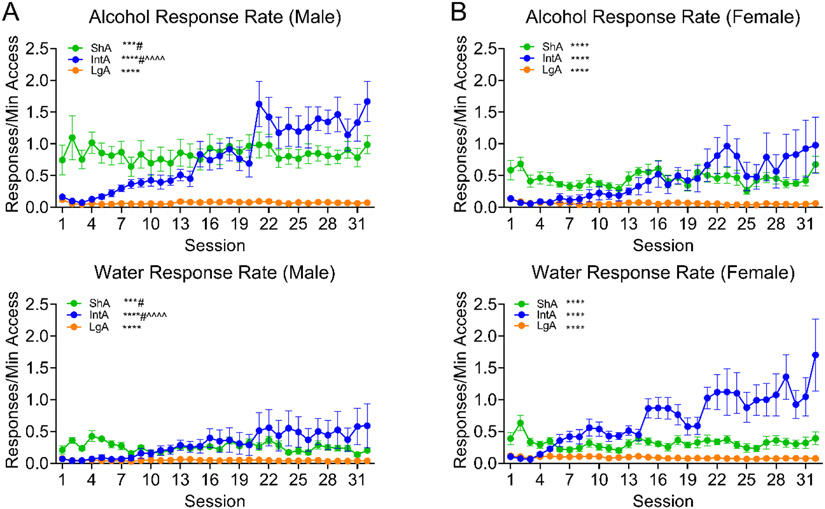

To compare the responding of the ShA, LgA, and IntA groups, data were first plotted as responses per minute-of-access, thereby accounting for the very different durations of alcohol access each group received, and that the IntA group received across sessions of decreasing alcohol access (Fig. 2A-B). Responding on both levers was analyzed over sessions for each different-access group, and, given the sex differences in pressing for alcohol and alcohol preference observed during 30-min alcohol self-administration sessions, different-access training data were analyzed split by sex to determine possible differences in responding between males and females (Fig. 2A-B).

Figure 2.

Responses on the alcohol and water lever are shown for the three groups across 32 different-access sessions. A. Male rats’ alcohol responses (upper) and responses for water (lower) are shown. The males in each of the three groups increased their total responses across sessions, and both the IntA and ShA made significantly more responses for alcohol than for water. The IntA males increased their alcohol responses but not their water responses across the sessions. B. Female rats’ alcohol responding (upper) and water responding (lower) is shown. Females in each of the three groups increased their total responding across sessions. Alcohol and water responding data is split into upper and lower panels to allow their visualization, however, statistical markers in this figure indicate effects resulting from analysis including Lever as a factor (i.e., upper and lower panel data were analyzed together for each group). ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001 main effect of Session; #p<0.05 main effect of Lever; ^^^^p<0.0001 Session x Lever interaction.

The ShA males increased their responding over sessions and responded more for alcohol than water across all sessions (Session: F (31, 217) = 2.232, p=0.0005; F (1, 7) = 11.69, p=0.0112; F (31, 217) = 0.7348, p=0.8463). The ShA females also increased their responding over the sessions, responded similarly on the two levers (Session: F (31, 217) = 2.930, p<0.0001; Lever: F (1, 7) = 2.596, p=0.1511; F (31, 217) = 0.7066, p=0.8755). Within the LgA group, both the males and females significantly increased their response rate across the sessions, similarly for the two levers (Figs. 2A-B; Males: Session: F (31, 217) = 6.085, p–0.0001; Lever: F (1, 7) = 1.244, p=0.3015; Session x Lever: F (31, 217) = 1.269, p=0.1662; Females: Session: F (31, 217) = 7.408, p<0.0001; Lever: F (1, 7) = 1.577, p=0.2495; F (31, 217) = 1.011, p=0.4574). Although the main effect of Session was highly significant when analyzing the LgA data, it is worth noting that the LgA rats did not dramatically change their drinking across sessions in this phase. In fact, it appears that the main effect of Session detected for LgA rats is mainly driven by their responding being quite different during the first two sessions of this phase when the rats appeared to be adjusting to the transition between training on 30-min and 16-h sessions.

The IntA males demonstrated a dramatic increase in response rate across sessions, which was greater for the alcohol lever (Session: F (31, 217) = 10.81, p<0.0001; Lever: F (1, 7) = 5.694, p=0.0484; Session x Lever: F (31, 217) = 3.374, p<0.0001). The IntA females also dramatically increased lever pressing across sessions, however, this was true for both levers (Session: F (31, 186) = 17.07, p<0.0001; Lever: F (1, 6) = 0.9319, p=0.3716; Session x Lever: F (31, 186) = 0.4816, p=0.9910). This pattern of behavior is reminiscent of the females’ response pattern during the 30-min self-administration sessions and appears to be the result of an amplification of their predisposition toward higher water consumption relative to males (water consumption during different-access training for all groups, split by sex, are plotted in Supplemental Figure S3). Because the rats in the LgA and IntA groups took a few sessions to stabilize once switched from 30-min to 16-h sessions, the third and final 60-min/hour access session for both the LgA and IntA was used as the baseline session for many-to-one post-hoc comparisons between sessions (i.e., session 3 was compared against all prior and following sessions, to determine where the differences across sessions occurred; Fig. 2A-B).

Figure 3 A-B shows the rate of alcohol consumption normalized to bodyweight for males and females during different-access training (i.e., g/kg/h-access). ShA and LgA rats of both sexes demonstrated relatively stable consumption of alcohol across different-access training. In contrast, male and female IntA rats increased their rate of alcohol consumption drastically over sessions. The IntA males and females initially responded at approximately the same rate as their LgA counterparts, but by the end of this phase, matched or exceeded the higher-intensity of drinking displayed by their ShA counterparts (Males (Fig. 3A): (Session: F (4.465, 93.77) = 4.506, p=0.0015; Group: F (2, 21) = 12.56, p=0.0003; Session x Group: F (62, 651) = 3.999, p<0.0001); Females (Fig. 3B): (Session: F (62, 620) = 3.575, p<0.0001; Group: F (2, 20) = 6.227, p=0.0079; Session x Group: F (62, 620) = 3.575, p<0.0001). To directly compare the behavior of male and female rats trained under each different-access condition, we additionally conducted Sex x Session analyses of responding and alcohol consumption data within the ShA, LgA, and IntA groups. We detected a significant Sex x Session interaction for LgA rats’ responding (Fig. 2; F (31,434) = 1.787, p=0.0067) and consumption data (Fig. 3; F (31, 434) = 2.611, p=0.0001). However, post-hoc analyses indicated that male and female LgA rats significantly differed only in terms of alcohol consumed during session 1 and 2 (ps < 0.01) and not on any of the subsequent 30 sessions (ps>0.1). As noted above, the IntA and LgA took a couple of sessions to stabilize in responding when transitioning from 30-min to 16-h sessions, and it appears that the female LgA consumed at a higher rate than the male LgA during these two sessions. This does not appear to be representative of the behavior observed in the rest of the different-access phase as we did not observe any other significant main effect or interaction involving Sex while conducting these analyses, and thus, these sex-difference analyses support the notion that the response pattern of males and females were not remarkably different during different-access training.

The alcohol preference of the males (Fig. 3C) did not differ across sessions or between groups (Session: F (5.142, 108.0) = 0.8305, p=0.5335; Group: F (2, 21) = 0.9437, p=0.4051; Session x Group: F (62, 651) = 0.9503, p=0.5858). The same was found after analyzing the alcohol preference of the females (Fig. 3D; Session: F (8.789, 175.8) = 1.567, p=0.1304; Group: F (2, 20) = 2.515, p=0.1061; Session x Group: F (62, 620) = 1.076, p=0.3295).

To confirm that the IntA group successfully learned each new access length, the discrimination ratio was calculated (presses during access periods/presses during non-access periods). The discrimination ratio of both males and females increased across IntA sessions, with males maintaining a slightly higher discrimination ratio than the females (Fig. 4A; Session: F (28, 364) = 13.81, p<0.0001; Sex: F (1, 13) = 8.546, p=0.0119; Session x Sex: F (28, 364) = 1.315, p=0.1347).

Figure 4.

Task performance of males and females during 32 IntA sessions A. To assess accuracy of responding, the discrimination ratio (Access/Non-Access responses) of the IntA males and females is plotted across the 32 sessions during which the IntA group received decreasing alcohol access. Both the IntA males and females increased their discrimination to high levels across sessions. In general, males maintained a higher discrimination ratio than females. B. To assess task engagement, the percentage of total access periods during which at least one response was made is plotted for male and female IntA rats across the IntA sessions. The percentage for both the males and females sharply decreased as periods of non-access were first introduced, before slightly increasing and remaining relatively stable across the remaining sessions. In general, the females responded during more access periods than the males, across sessions. C. and D. show, respectively, the binge-like alcohol drinking of an exemplar male and female IntA rat. A 2-min-access/hour session is shown for each rat, with blue stripes used to indicate 2-min access periods during which alcohol consumption occurred, and red stripes used to indicate 2-min access periods during which no alcohol consumption occurred. **** p<0.0001 main effect of Session, ##p<0.01, #p<0.05 main effect of Sex

The number of access periods during which the IntA rats responded (i.e., out of a possible 16 access periods) was also analyzed to assess task engagement during sessions, as the length of alcohol access periods was systematically decreased across sessions (Fig. 4B). The percent of access periods with at least one response was 75-100 % when access was reduced to 40-min per hour and dropped markedly when access was cut to 20- then 10-min per session. As the IntA rats received multiple 10-min per hour access sessions, the group’s percentage recovered and stabilized, hovering near 50 percent for the remainder of the IntA sessions (Fig. 4B). Both males and females followed this general pattern across sessions of decreasing access length, with the female IntA rats maintaining a higher percentage across sessions (Session: F (31, 403) = 19.46, p<0.0001; Sex: F (1, 13) = 9.796, p=0.0080; Session x Sex: F (31, 403) = 0.7245, p=0.8621).

Figure 4C-D shows individual data for two IntA rats, 1 male and 1 female, selected as exemplars of binge-like alcohol consumption displayed during 2-min per hour access sessions. Both of these rats demonstrated intense alcohol consumption coincident with the onset of the click stimulus at the beginning of the brief access periods. This same pattern of behavior was not directed toward the water lever, and non-access period responding was virtually non-existent, which contributed to the high discrimination ratio observed in the IntA rats (Fig. 4A).

3.3. Alcohol Seeking in the Presence of Cues Test

Data from seeking tests on day 1 and day 21 were similar between males and females. To formally compare the behavior of male and female rats, we conducted Sex x Session analyses for the ShA, LgA, and IntA groups. We did not detect any significant main effect or interaction involving Sex for any of the different-access groups. Thus, to maximize statistical power for analyzing differences between different-access groups, data were collapsed by sex (the alcohol-seeking test data is shown split by sex in Supplemental Figure S4). Figure 5A shows the interaction between the groups across testing days. The ShA responded the most on day 1 testing, followed by IntA and LgA. From day 1 to day 21, the ShA decreased their overall pressing, while the IntA did not change and the LgA increased their pressing. This convergence in pressing from day 1 to day 21 meant the three groups did not respond significantly differently at day 21 (Fig. 5A; Day: F (1, 44) = 1.365, p=0.2490; Group: F (2, 44) = 8.935, p=0.0006; Day x Group: F (2, 44) = 13.05, p<0.0001).

It was hypothesized that IntA would press the most during the seeking tests. However, the ShA pressed the most on day 1, and no groups were different at day 21. Given that the three groups were trained with different access period lengths (ShA: 30-minutes, IntA: 2-minutes, LgA: 16-hours), the two seeking tests were further broken down into 20-minute blocks to examine whether the groups pressing might change across components of each 1h seeking test (Fig. 5B). On the day 1 test, ShA rats had the highest pressing at 20-min, followed by IntA and then LgA, mimicking the results seen in the analysis of the whole seeking tests. At 40-min the ShA maintained the highest pressing, but the IntA and LgA were no longer different. At 60-min, the three groups all demonstrated extinction of seeking behavior and were no longer significantly different from each other (Block: F (2, 88) = 49.66, p<0.0001; Group: F (2, 44) = 21.08, p<0.0001; Block x Group: F (4, 88) = 6.481, p=0.0001). During the day 21 test, the groups responded similarly and extinguished similarly across the three 20-min blocks (Block: F (2, 88) = 84.26, p<0.0001; Group: F (2, 44) = 0.8759, p=0.4236; Block x Group: F (4, 88) = 0.8703, p=0.4851).

Given that the IntA were trained on a 2-min access period directly before the seeking tests, it could be expected that, despite the continuous presence of the access-signaling click during the seeking-test, they might press intensely during the first 2-min of the seeking tests, and then decrease their pressing for the remainder of the 1-h test. To further examine this possibility, the first two minutes of the seeking tests were analyzed (Fig. S4). Even when analyzing only the first 2-min of each test, the overall session trends were preserved, as ShA maintained the highest pressing out of the three groups at day 1, and the groups were not different at day 21 (Fig. S4).

3.4. Punished Alcohol Drinking Test

Following the alcohol seeking tests, the three groups started reacquisition, and from the first session of reacquisition displayed significantly different rates of alcohol consumption. Despite the length of time (more than 21 days) between alcohol access sessions, the order of drinking intensity between the groups was well-maintained from the last alcohol-access training session (IntA > ShA > LgA; rate of consumption from last different-access session to first reacquisition session is shown split by sex in Supplemental Figure S5). There was a significant interaction between Session and Group during reacquisition, as responding stabilized over reacquisition sessions (Session: F (3.065, 134.8) = 11.09, p<0.0001; Group: F (2, 44) = 10.46, p=0.0002; Session x Group: F (8, 176) = 3.018, p=0.0034).

Following 5 sessions of reacquisition, quinine was added to the available alcohol solution in ascending concentrations. To formally compare the behavior of male and female rats during quinine adulteration, we conducted Sex x Session analyses for the ShA, LgA, and IntA groups. We did not detect any significant main effect or interaction involving Sex for any of different-access groups. Thus, to maximize statistical power for analyzing differences between different-access groups, data were collapsed by sex (the rate of alcohol consumption across the doses of quinine tested are shown split by sex in Supplemental Figure S6). The three groups differently persisted in their alcohol consumption during quinine adulteration testing, with the IntA most persistent (Fig. 6A; Quinine: F (2.891, 127.2) = 8.479, p<0.0001; Group: F (2, 44) = 10.69, p=0.0002; Quinine x Group: F (10, 220) = 1.940, p=0.0412).

Figure 6B-D shows the correlation between unpunished and punished drinking for each group (average of re-acquisition and 0 mg/kg baseline sessions vs. average of two highest quinine concentrations tested where quinine effect plateaued). These panels better illustrate the relationship between unpunished and punished drinking within each group relative to their own baseline behavior (Hopf et al., 2010; Hopf & Lesscher, 2014). Values closer to the black line indicate less change in drinking upon the imposition of punishment. Points above the line indicate increased drinking during punishment while points below the line indicate that punishment suppressed alcohol drinking. IntA rats maintained the steepest slope, and a significant correlation between punished and unpunished drinking, indicating the most persistent alcohol drinking in the face of punishment. The LgA group had the next steepest slope, also with a significant correlation between punished and unpunished drinking. Finally, the ShA group had the shallowest slope, and punished drinking was not significantly correlated with unpunished drinking, indicating that their behavior was most sensitive to quinine adulteration.

Figure 7E-F shows the result of training Wistar rats on intermittent access operant alcohol self-administration. Figs. 7A-C show the behavior of the to-be-split groups during their initial training where all rats received 10 sessions of the same 30-min self-administration training. There was a significant Session x Lever interaction as both to-be-split groups responded more on the alcohol lever than the water lever over sessions (Fig 7A; Session x Lever interaction, F (9, 126) = 5.167, p<0.0001). Alcohol consumption (Fig 7B; Main effect of Session, F (9, 126) = 2.857, p=0.0042) and preference (Fig 7C; Main effect of Session, F (9, 126) = 4.703, p<0.0001) increased significantly over these 10 training sessions. In the next phase, where IntA rats received 5 min of alcohol access per hour (governed by insertion of the retractable alcohol and water levers for 5 min at the beginning of each hour of the session). We observed that across this phase, both groups responded more for alcohol than water and that the IntA group responded at a higher rate than the ContA rats, a significant interaction suggested further that the IntA elevated their pressing for alcohol relative to water to a greater extent than the ContA rats (Fig 7D; Main effect of Lever, F (1, 14) = 11.05, p=0.0050, main effect of Group F (1, 14) = 20.33, p=0.0005, Lever x Group interaction, F (1, 14) = 5.798, p=0.0304). The IntA Wistar rats displayed a much higher rate of alcohol consumption compared to ContA Wistar rats across this phase (Fig. 7E; Main effect of Group, F (1, 14) = 19.40, p=0.0006). Finally, preference for alcohol increased across this phase in both groups, with a significant interaction indicating some individual-session differences with groups converging by the end of the phase to a similar alcohol preference (Fig 7F; Main effect of Session, F (9, 126) = 6.776, p<0.0001, Session x Group interaction, F (9, 126) = 3.120, p=0.0020).

Figure 8(A-C) demonstrate the circadian control of the drinking behavior shown in Fig. 7E. The last 5 sessions of this 10 session phase were averaged in order to generate representative drinking in each phase for each rat (by using 2-h blocks, this collected together the 2, 5-min access periods for IntA rats). Interestingly, we found evidence that the circadian control of drinking continued to be a relevant factor in the behavior of both male and female, IntA and ContA rats. For the “light turns on” period (first 4h; Fig. 8A; IntA main effect of Light F (1, 6) = 41.42, p=0.0007; ContA main effect of Light F (1, 6) = 107.9, p<0.0001), for the “light turns off’ period (final 4h; Fig 8C; IntA main effect of Light F (1, 6) = 6.517, p=0.0433; ContA main effect of Light F (1, 6) = 34.46, p=0.0011). In analyzing the middle 8h portion of the session, we noted that ContA but not IntA decreased consumption across time, in line with the maintenance of a higher rate of alcohol consumption in IntA rats (Fig 8B; IntA main effect of 2-h block, F (3, 18) = 2.453, p=0.0965, ContA main effect of 2-h block, F (3, 18) = 5.221, p=0.0091). The only place we observed sex differences in this analysis was in IntA male vs. female rats in the first 2-h of the session (Fig 8A; Sex x Light interaction, F (1, 6) 6.637, p=0.0420; male vs female post-hoc comparison during first 2-h, p=0.0353). This appears to suggest that an enhanced frontloading of alcohol behavior in male rats occurs specifically during IntA training that may be relevant to understand how male and female rats might differently engage in this task.

4. Discussion

This study found that, in both male and female NIH Heterogeneous Stock Rats, IntA to operant self-administration of alcohol caused an intensification of alcohol consumption during periods of access when compared to those from LgA or ShA. The IntA group also demonstrated increased responding on the day 1 seeking test compared to the LgA group, although the ShA rats responded the most, and all rats responded similarly during the day 21 test for ‘incubation’ of alcohol seeking. A clearer result was observed during re-acquisition and quinine-punished drinking tests, as IntA-trained rats immediately returned to their previous binge-like pattern of responding and demonstrated the greatest persistence of the groups in the face of quinine-adulteration of their alcohol solution. The increased binge-like drinking and increased resistance to quinine punishment observed in the IntA group are consistent with previous studies with drugs from other classes, demonstrating that IntA self-administration can produce more “addiction-like” behavior compared to continuous-access self-administration (Calipari et al., 2013; Calipari et al., 2015; Kawa, Allain, et al., 2019; Kawa, Valenta, et al., 2019).

Overall, the current study found that the LgA rats consumed the most total alcohol, which is not surprising given that they received much more self-administration access than the ShA and IntA rats (see raw data in Supplemental Data File). The ShA and IntA, however, ended their training on different-access sessions with similar total access per session (30 min and 32 min, respectively), and both groups exhibited a similarly high rate of alcohol consumption relative to LgA rats. Despite similar total amounts of alcohol access per day and similar total alcohol consumption per day in the IntA and ShA groups, the different access regimens of these groups (1, 30-minute access period vs. 16, 2-minute access periods, respectively) resulted in different patterns of alcohol seeking assessed by the cue-induced seeking test (enhanced seeking in ShA rats) and punishment-resistant drinking assessed in the punishment test (enhanced drinking in IntA rats). One potential interpretation of the present data is that taste habituation may have contributed to the intensification of binge-like drinking in IntA rats, alcohol seeking in ShA rats, and the persistence of quinine-adulterated drinking in IntA rats. For example, Loney and Meyer reported that both prior alcohol exposure and prior quinine exposure increased acceptance of later alcohol presentations (2018). In the present dataset, however, we should expect that taste habituation occurs most strongly in in the group of rats with the most total alcohol consumption experience (i.e., LgA rather than the IntA or ShA rats). It is clear from these data that length of self-administration access and total consumption are not the only factors that influence the expression of addiction-like behavior. This novel finding in terms of operant self-administration of orally consumed alcohol reinforcement is in agreement with results reported for self-administration of intravenous cocaine infusions (Calipari et al., 2014; Calipari et al., 2013; Calipari et al., 2015).

The finding that intermittent access to operant alcohol produced an increase in binge-like alcohol consumption in rats is also in agreement with effects reported in homecage-based models of binge-like alcohol drinking, such as intermittent access 2-bottle choice (IA2BC) and drinking in the dark (DID). IA2BC involves giving alternating bottles of alcohol and water, typically rats are given alcohol on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday in the homecage. The drinking of rats given IA2BC was intensified compared to rats given continuous 2BC (Simms et al., 2008; Wise, 1973). The drinking-in-the dark model of binge-like drinking was first utilized in the study of AUD in mice (Rhodes et al., 2005; Thiele & Navarro, 2014). Drinking in the dark presents access to alcohol for a limited amount of time shortly after the beginning of the dark period of the light:dark cycle, usually 2 hours of access to alcohol, and this is done for several days. In mice it was found that drinking in the dark produced intensified binge-like drinking (Rhodes et al., 2005; Thiele & Navarro, 2014). Adaptation of the drinking in the dark model for rats has shown that it is able to produce similar intensification of binge-like drinking, with increased hourly intake compared to IA2BC rats (Holgate et al., 2017). In rats, the use of IA2BC and DID were both able to produce BALs that meet the 80 mg/dL criteria used to define binge-drinking episodes by the NIAAA (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2021). Our study found a similar g/kg of consumption in IntA rats during operant self-administration access periods when compared to the homecage drinking of studies using IA2BC and DID models, suggesting that intermittent access to operant alcohol self-administration could be used as a model of binge-like alcohol consumption.

It is worth noting that despite the extensive training and high discrimination ratios achieved by IntA rats, they did not drink alcohol on approximately 50% of trials. This pattern of responding is likely due to satiety, generally characterized by periods of non-response following reinforcers, that gradually increase in length (Sidman & Stebbins, 1954). The satiety effect was similarly observed while modeling IntA self-administration of saccharin, a highly pallatable non-drug reinforcer (Beasley et al., 2022). It is worth noting that the intensity of IntA rats’ alcohol self-administration in the present study is somewhat masked by the fact that IntA rats did not drink alcohol on approximately 50% of trials. As we report alcohol consumption rate as a function of alcohol consumed over all alcohol-access periods in the session, this means that, in fact, the local rate of alcohol consumption during IntA rats’ binge-like episodes is approximately double what is shown in the aggregate data. Unfortunately, we were not able to assess BALs in the moments following these binge-like drinking episodes. Because the IntA rats in the present study consumed alcohol sporadically between access periods, and because the IntA behavior was maintained over long sessions (i.e., 16h), sampling blood at the moment of peak intoxication for each animal, while also not disturbing the ongoing behavioral measurement, would not have been feasible.

In testing cue-motivated alcohol seeking under extinction conditions, the IntA rats demonstrated increased seeking compared to the LgA at day 1, though neither the IntA or LgA rats demonstrated greater seeking than the ShA. This was true even when considering only the first 20 min of the test or when considering the first 2-min of the test (i.e., to match the period of access that the IntA rats had been trained to respond during). At the day 21 test, no differences between groups were observed. In terms of incubation of seeking across time, the LgA rats significantly increased their responding from day 1 to day 21, demonstrating an incubation of alcohol seeking. In contrast, the IntA maintained their responding from day 1 to day 21, while the ShA rats decreased their responding from day 1 to day 21. These findings are quite different from effects observed with intravenous cocaine, as cocaine seeking was reported to increase from day 2 to day 29 for both IntA and LgA rats (Nicolas et al., 2019). These findings are however reminiscent of the increased day 1 heroin seeking of IntA-heroin rats compared to LgA-heroin rats, a difference which does not appear to persist to day 21 of testing, as recently reported by D’Ottavio et al. (2021). It may be the case that alcohol-seeking behavior is more similar in form to opioid-seeking behavior than stimulant-seeking behavior. The psychomotor activating properties of stimulant drugs likely contribute to the high rates of seeking-behavior in the presence of drug-paired stimuli. It is difficult to make any strong assertion however, as seeking-behavior and incubation of seeking-behavior are dependent on many procedural factors which may alter the outcome (Shaham et al., 2003). It is worth noting here also for example that these psychostimulant and opioid incubation-of-seeking studies were not conducted in NIH Heterogeneous Stock rats as in the present study. In the initial -and perhaps only other- report on the incubation of alcohol seeking in rodents (Bienkowski et al., 2004), the phenomenon was demonstrated under conditions different from the present report. Notably, a between-subjects design was used, a longer day 56 timepoint was included, and cue-evoked alcohol seeking was measured separately from extinction responding. Interestingly, the authors of that study noted that the cue-evoked seeking which was observed did not appear correlated with earlier alcohol drinking nor with seeking-behavior measured under non-cued extinction conditions in the preceding session component (Bienkowski et al., 2004). While we were able to demonstrate an incubation of alcohol seeking in our LgA rats, it appears that the length and/or frequency of alcohol access during training contributes to the display of alcohol seeking during testing for ‘incubated’ alcohol seeking, as we did not observe an incubation of alcohol seeking in our IntA or ShA rats. In any case, alcohol-seeking behavior does not appear to be as robust as psychostimulant- or opioid-seeking behavior, and in general appears highly sensitive to details of experimental design (Ginsburg & Lamb, 2015).

Human AUD has been associated with continued consumption despite negative or aversive consequences and animal models have sought to model this facet of AUD utilizing foot shock and quinine (Hopf & Lesscher, 2014). Quinine punishment has been shown to activate similar cortical areas to foot-shock punishment, and these brain regions are distinct from those activated by unpunished alcohol intake (Seif et al., 2013). The IntA rats in our current study demonstrated the most persistent alcohol drinking in the face of punishment when compared to ShA or LgA rats, and this is in agreement with demonstrations that 3-4 months of intermittent access to two-bottle choice in the homecage (i.e., IA2BC) can produce more quinine-resistant alcohol drinking (Hopf et al., 2010). Indeed, intermittent access operant alcohol self-administration may be particularly useful in studying punished alcohol drinking.

There were some subtle differences observed between males and females in the current study. Although males and females did not differ in alcohol consumption after normalizing the data to account for bodyweight differences, male rats did exhibit a higher preference for alcohol. This appears to be due more to differences in water consumption than alcohol consumption, with females consistently consuming more water than males after accounting for bodyweight differences (Supplemental Figure S2). Likewise, while male IntA rats intensified their drinking of alcohol without much change in drinking of water, female IntA rats appeared to intensify their drinking of both alcohol and water. This was an unexpected observation made during the completion of the experiment that highlights the importance of considering differences in fluid intake between males and females when offering self-administered oral drug solutions. When examining water intake, there is evidence to suggest that females drink more water than males relative to their bodyweight (McGivern et al., 1996). This may be difficult to discern in most homecage alcohol drinking studies, as water is typically offered continuously by bottle in the homecage, and water intake may not be recorded or reported. In general, however, the patterns of alcohol-motivated behavior observed between different-access groups were comparable between male and female subjects, suggesting that this model might be suitable for further study of sex differences. It is worth noting that in general, females have been reported to consume more alcohol relative to bodyweight than male subjects (e.g., (Juárez & De Tomasi, 1999), but it appears that sex differences in alcohol consumption are more marked in homecage compared to operant self-administration models (Priddy et al., 2017). One reason we may not have observed sex differences in alcohol drinking in the present study is that genetic differences between the individual NIH Heterogenous Stock rats used may have overwhelmed any sex differences in operant alcohol self-administration. Future studies in larger cohorts of NIH Heterogeneous Stock rats will be crucial to determine the extent to which sex differences account for variance in alcohol drinking behavior. The experiment in Wistar rats which included a circadian-cue light demonstrated that circadian regulation of operant behavior occurs similarly in male and female, intermittent- and continuous-access trained rats (i.e., our hypotheses relating to breakdown of circadian control in IntA rats, and different-control between male and female rats were not supported). However, this experiment did suggest that male and female rats trained on the IntA procedure appear to be most different in the very first component of the session (this was not observed in ContA rats). This raises the possibility that the IntA procedure may engage “front loading” of alcohol consumption behavior more so in male than female rats.

Given the diversity seen in human AUD and the role of genetics in its development (Deak et al., 2019), it is a noteworthy strength that the presently reported effects were observed while using NIH Heterogeneous Stock rats which have considerable genetic diversity. Given the extensive training conducted in the NIH Heterogeneous Stock rat in order to ensure a stable baseline of alcohol self-administration, the present data suggests that it should be possible to implement the intermittent-access model of operant alcohol self-administration in other strains of rats, for example, the eight founding rat lines of this strain (Hansen & Spuhler, 1984; Woods & Mott, 2017). In support of this point, we provide a generalized replication experiment which demonstrated that the Wistar rat readily and robustly displays an enhanced rate of alcohol consumption when trained on an intermittent- compared with continuous-access operant self-administered procedure.

In conclusion, we propose that intermittent access to operant alcohol self-administration may be a useful approach to modelling binge-like alcohol self-administration in rats. This may be especially useful in probing the neurobiology of alcohol binge drinking, which contributes a major part of the individual and societal burden imposed by alcohol misuse.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure S1

A. During the session where each rat met the overnight criterion (100 combined presses on either lever) there was no difference in alcohol or water pressing between males or females. B. During the single 2h session there continued to be no difference between alcohol or water presses in either males or females. C. The final 1h session for each rat, in which each rat met the criterion to pass (10 combined presses on either lever), showed a main effect of sex as the males pressed significantly more than the females (Lever: F (1,90) = 3.431, p=0.0673; Sex: F(1,90) = 6.497, p=0.0125; Sex x Lever: F(1,90) = 0.08681, p=.7690). #p<0.05 between group effect.

Supplemental Figure S2

Water consumption (plotted as ml/kg) is shown by sex across 46, 30-min acquisition sessions. There was a main effect of both Session and Sex. The females maintained a higher water consumption as both males and females decreased their water consumption across the acquisition sessions (Session: F (45, 2025) = 9.096, p<0.0001; Sex: F (1, 45) = 27.70, p<0.0001; Session x Sex: F (45, 2025) = 1.103, p=0.2966). ****p<0.0001 main effect of Session; ####p<0.0001 main effect of Sex.

Supplemental Figure S3

A. Male water consumption is shown split by the three access groups (ShA, LgA, and IntA) across the 32 different-access sessions. There was a significant interaction between Group and Session as the IntA increased across sessions while the ShA and LgA remained relatively stable (Session: F (31, 651) = 1.975, p=0.0014; Group: F (2, 21) = 3.456, p<0.0504; Session x Group: F (62, 651) = 2.940, p<0.0001). B. There was also a significant interaction between Group and Session in the female’s water consumption. The ShA and LgA had relatively stable water consumption while the intensity of water consumption in the IntA drastically increased (Session: F (31,620) = 4.670, p<0.0001; Group: F (2,20) = 12.37, p=0.0003; Session x Group: F (62, 620) = 5.096), p<0.0001). ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01 main effect of Session; ###p<0.001 between group effect, ^^^p<0.0001 interaction.

Supplemental Figure S4

A. In the males, ShA had the highest seeking responses on day 1, compared to the IntA and LgA who were not different from each other. On day 21 the ShA decreased their responding and the LgA increased their responding. At day 21 no group was different from each other. B. After splitting seeking tests into 3, 20-min blocks, the ShA had the highest responding after 20-min but at 40 and 60-min the groups were not different. The groups were not different during any block on day 21. C. The ShA maintained the highest responding during the day 1 seeking test when examining the first two minutes, while the IntA and LgA were not different from each other. D. In females, ShA rats had significantly higher responding on day 1 compared to LgA rats (similar to the males, ShA females responded more than IntA females, but not significantly so; p=0.0643). The groups were not different from each other at day 21. Similarly to the males, the female LgA increased their responding between day 1 and day 21 tests, but not significantly so (p=0.0637). E. The ShA and IntA had higher responding in the first 20-min of the day 1 seeking test but the groups were not different at 40 or 60-min of day 1 or all of day 21. F. The ShA and IntA females have more seeking responses than the LgA in the first two minutes of day 1 but no differences are seen between the three groups in the first two minutes of day 21. In general, the trends observed in the lower statistical power male-only and female-only analyses were in line with the higher statistical power analysis where data were collapsed across Sex (main text Fig. 5). Specifically, the analysis of male-only and female-only data yielded a significant interaction term for data shown in Panels A, B -day 1 and not day 21-, C, D, E -day 1 and not day 21-, and F. For the sake of brevity, however, we do not report the full statistical output of those analyses here. S, L, and I are used to indicate difference from ShA, LgA, and IntA respectively, including when these groups differed from themselves between test days.

Supplemental Figure S5

Effect of alcohol deprivation on alcohol consumption. A. The ShA and IntA males consumed more alcohol than the LgA males, and this pattern was maintained as overall alcohol consumption increased across the phases (Phase: F (1,21) = 8.311, p=0.0089; Group: F (2,21) = 12.53, p=0.0003; Phase x Group: F (2,21) = 1.905, p=0.1736). B. The female alcohol consumption was different between groups (mainly driven by the difference between IntA and LgA groups), but there was no difference between acquisition and reacquisition phases (Phase: F (1,20) = 2.593, p=0.1230; Group: F (2,20) = 4.753, p=0.0205; Phase x Group: F (2,20) = 1.136, p=0.3409). In order to increase the power for detecting alcohol deprivation effects, the data was also analyzed combined across Sex. Here, significant main effects of Phase (F (1, 44) = 7.853, p=0.0075) and Group (F (2, 44) = 12.13, p<0.0001) were observed, but without evidence of an interaction (F (2, 44) = 2.335, p=0.1087). While it was clear that the groups responded more after the alcohol deprivation period, and while it was clear that ShA (p = 0.0027) and IntA (p<0.0001) groups responded more than the LgA group, we did not find an interaction of Phase x Group to support the idea that one group may demonstrate a stronger alcohol deprivation effect compared to another. For this reason, we did not pursue further post-hoc testing. ***p<0.001, *p<0.05 Main effect of Phase (Analysis within Sex); ##p<0.01 Main effect of group (Analysis within Sex).

Supplemental Figure S6