Abstract

Objective:

Lassa fever (LF) is caused by a viral pathogen with pandemic potential. LF vaccines have the potential to prevent significant disease in individuals at risk of infection, but no such vaccine has been licensed or authorized for use thus far. We conducted a scoping review to identify and compare registered phase 1, 2 or 3 clinical trials of LF vaccine candidates, and appraise the current trajectory of LF vaccine development.

Method:

We systematically searched 24 trial registries, PubMed, relevant conference abstracts and additional grey literature sources up to October 27, 2022. After extracting key details about each vaccine candidate and each eligible trial, we qualitatively synthesized the evidence.

Results:

We found that four LF vaccine candidates (INO-4500, MV-LASV, rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC, and EBS-LASV) have entered the clinical stage of assessment. Five phase 1 trials (all focused on healthy adults) and one phase 2 trial (involving a broader age group from six months to 70 years) evaluating one of these vaccines have been registered to date. Here, we describe the characteristics of each vaccine candidate and trial and compare them to WHO’s target product profile for Lassa vaccines.

Conclusion:

Though LF vaccine development is still in early stages, current progress towards a safe and effective vaccine is encouraging.

Keywords: Vaccine candidate, Clinical trial, Vaccine development, Priority pathogens, LASV, Viral hemorrhagic fever

INTRODUCTION

Longitudinal studies conducted in Sierra Leone in the 1980s indicated that Lassa virus (LASV) is responsible for an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 cases of Lassa fever (LF) and 5000 deaths occurring annually in West Africa alone (1). However, recent modelled estimates suggest a much higher burden of human infections, predicting between 897,700 and 4,383,600 annual cases in the region (2). LF is a zoonotic disease, with at least one mouse species identified as the reservoir (3). Direct contact with fluids (e.g. urine, saliva or blood) of LASV-infected rodents is the primary route of transmission, along with indirect exposure to contaminated surfaces and foods (4). Human-to-human transmission can also occur after exposure to bodily fluids of LASV-infected individuals, especially in a household or healthcare setting (4). LASV is a leading cause of hemorrhagic fever globally (5), and the incidence of LF has increased significantly in recent years, largely reflecting improved surveillance (6, 7). While an estimated 80% of cases are asymptomatic, those with symptoms may experience severe health outcomes, with a case-fatality rate of roughly 20% among hospitalized cases (1). Poor outcomes are more common among some individuals, including pregnant women and their fetuses (8, 9), and sequelae (e.g., hearing loss, ataxia) are also frequently observed among survivors regardless of clinical severity (9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Various factors, such as the risk of outbreaks, the increasing burden of disease, the existence of several difficult-to-control animal reservoirs, and the potential for person-to-person transmission, make LASV a priority pathogen, as indicated in WHO’s Research and Development (R&D) Blueprint list for Action to Prevent Epidemics (14). Hence, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) included LF among priority diseases for which a vaccine is urgently needed (15, 16). The impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on healthcare resources that would have been devoted to monitoring, preventing, and controlling numerous infectious diseases in West Africa (and globally) (17), likely coupled with greater hesitancy to seek medical attention during the pandemic (18, 19), further support the need for improving LF prevention and control measures (7). In March 2022, the Global Pandemic Preparedness Summit took place in London and resulted in a joint commitment to devote US$ 1.5 billion to CEPI to support the ambitious plan to compress vaccine development timelines to 100 days for re-emerging and newly emerging pathogens that could cause the next pandemic, including LASV (20).

Preventive measures are crucial in reducing the burden of disease attributable to LASV. Monitoring progress towards developing preventive measures is essential to raising awareness about the state of progress and identifying potential issues, opportunities, and priorities that should be addressed during vaccine development. Presently, no vaccines are licensed or authorized to reduce the risk of infection or disease caused by Lassa virus. While vaccination may prevent infection among those exposed to LASV and/or progression to severe disease in those infected with LASV, vaccination alone will not prevent spillover events from animal reservoirs and other measures remain necessary to control the spread of Lassa virus. Current prevention efforts focus mainly on educating communities to avoid direct contact with animal reservoirs by improving sanitation and ensuring proper food storage to discourage rodents from entering homes, as well as infection control and prevention practices in healthcare facilities to reduce person-to-person transmission (21). However, the progressive anthropization leading to closer and more frequent interactions between humans and wildlife carrying LASV (22, 23), along with the significant zoonotic host diversity, make contact precautions challenging to implement and sustain on a broad scale and are thus poorly effective at controlling LF.

LF vaccine research efforts began in the 1970s (24) and several LF vaccine candidates are currently under development, yet multiple factors have made LF vaccine development particularly challenging thus far. For example, LASV strains show extensive genetic diversity, which seems to cluster with geographic location rather than over time (25). Indeed, genomic analysis during a 2018 LF outbreak in Nigeria suggest that the increased incidence of LF was attributable to ongoing zoonotic infection, with high viral diversity, rather than transmission of a dominant strain from person-to-person (26). To ensure broad coverage, LASV vaccine development and evaluation must take this degree of diversity into account (27, 28).

Evaluating the safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of LASV vaccine candidates is a challenging task given the epidemiology of the disease and multiple other factors, including the acceptability of taking part in a clinical trial for a novel vaccine. The sporadic nature of LF outbreaks makes planning and implementing efficacy trials with disease endpoints difficult to complete in a timely manner. A low incidence of LF in a given region at a given time will require longer follow-up of clinical trial participants in order to ensure robust efficacy estimates (13). Incorporating rodent surveillance efforts, in addition to tracking LF cases in humans, may help more accurately estimate the risk of infection from spillover events and is thus critical to the selection of suitable clinical trial sites. In addition, additional research is needed to better understand the immune response to LASV infection. There are limited data from non-human primate (NHP) models and a broadly accepted immunologic correlate of protection in humans has yet to be identified (29). Importantly, most preclinical trials assessing LF vaccine candidates have evaluated immune responses in mice and guinea pigs, but since LASV is a rodent-borne virus, rodents may not be ideal animal models for the evaluation of a potential LF vaccine, as the immune response in mice and guinea pigs may differ to that of humans (30, 31, 32).

Recent studies have focused on the preclinical phases of LF vaccine development and evaluation, with an emphasis on the advantages and disadvantages of utilizing different technologies (5, 31). The first LF vaccine candidates have entered the clinical phase of assessment in 2019, and – given that there is a renewed global commitment to develop a LF vaccine as a matter of urgency (20) – we conducted a review of the current LF vaccine development landscape. Our aim was to assess current progress on clinical evaluation of LF vaccine candidates, to identify key challenges to evaluating LF vaccine candidates, and to consider opportunities for expediting LF vaccine candidate evaluation in the future. Thus, we (1) identified all registered phase 1, 2 or 3 clinical trials evaluating one or more LF vaccine candidates; (2) compared the characteristics of each LF vaccine candidate and each clinical trial designed to evaluate each candidate, and (3) highlighted key strengths and challenges of determining the immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety of these vaccine candidates given the design and scope of current trials. Our overall aim was to appraise the current trajectory of LF vaccine development.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review of clinical trials of LF vaccine candidates based on a pre-specified protocol that was refined throughout the process as per standard practices for this type of reviews.

Data sources and search strategies

To identify LF vaccine candidates that have begun evaluation in clinical trials and to identify all relevant clinical trials evaluating the immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety of these candidates, we systematically searched 24 international and national clinical trial registries (Table 1) using the following terms: “Lassa”, “Lassa fever”, “Lassa virus”, “LASV”, “Arenavirus”, “Arenaviridae”, “Hemorrhagic fever”. In addition, we searched for relevant reports, press releases and scientific publications through a series of systematic searches across websites of pharmaceutical companies and other organizations that are known to be involved in LF vaccine research based on information reported in publicly accessible documents from the WHO, the Africa CDC, and CEPI. In order to retrieve published results and other information about eligible trials, we searched PubMed utilizing a combination of keywords related to the concepts of “Lassa fever” and “vaccine”, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms, i.e. indexing terms used to describe the subject of an article, and restricted certain search queries to title and abstract (“tiab”): (“Lassa virus”[Mesh] OR “Lassa Fever”[Mesh] OR “Lassa”[tiab]) AND (“Immunization”[Mesh] OR “Vaccination”[Mesh] OR “Vaccines”[Mesh] OR “Vaccine*”[tiab]). We also manually screened the proceedings of the following key international conferences held in 2020 or later: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) (2020, 2021), International Conference on Public Health in Africa (CPHIA) (2021), European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) (2020, 2021, 2022), European Congress of Tropical Medicine and International Health (ECTMIH) (2021), European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) Forum (2021), Infectious Disease (ID) Week (2020, 2021, 2022), International Vaccines Congress (2020, 2021, 2022).

Table 1:

List of clinical trial registries utilized to identify clinical trials of Lassa fever vaccine candidates

| Clinical Trial Registry | Link to Registry |

|---|---|

| Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ANZCTR) | https://www.anzctr.org.au |

| Brazilian Clinical Trial Registry (ReBec) | https://ensaiosclinicos.gov.br |

| Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR) | http://www.chictr.org.cn/index.aspx |

| Clinical Research Information Service (CRiS), Rep. of Korea | https://cris.nih.go.kr/cris/info/introduce.do?search_lang=E&lang=E |

| Clinical Trials Registry - India (CTRI) | http://ctri.nic.in/Clinicaltrials/login.php |

| Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials (RPCEC) | https://rpcec.sld.cu |

| EU Clinical Trials Register (EU-CTR) | https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search |

| German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS) | https://www.drks.de/drks_web/ |

| Health Canada Clinical Trial database | https://health-products.canada.ca/ctdb-bdec/index-eng.jsp |

| Indonesia Clinical Research Registry | https://www.ina-registry.org/index.php?act=registry_trials |

| International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number ISRCTN) Registry) | https://www.isrctn.com |

| Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT) | https://www.irct.ir |

| Japan Registry of Clinical Trials (jRCT) | https://rctportal.niph.go.jp/en/ |

| Lebanon Clinical Trials Registry (LBCTR) | https://lbctr.moph.gov.lb |

| Philippine Health Research Registry | https://registry.healthresearch.ph/index.php/registry |

| Thai Clinical Trials Registry (TCTR) | https://www.thaiclinicaltrials.org |

| The Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR) | https://www.trialregister.nl |

| Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (PACTR) | https://pactr.samrc.ac.za |

| Peruvian Clinical Trial Registry (REPEC) | https://ensayosclinicos-repec.ins.gob.pe/en/ |

| Russian Clinical Trials Register | http://clinicaltrialsregister.ru |

| Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (SLCTR) | https://slctr.lk |

| Swiss National Clinical Trial portal | https://www.kofam.ch/en/snctp-portal/searching-for-a-clinical-trial/ |

| U.S. Clinical Trial Registry | https://clinicaltrials.gov |

| WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) | https://trialsearch.who.int/Default.aspx |

ASTMH, American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene; CPHIA, International Conference on Public Health in Africa; ECCMID, European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases; ECTMIH, European Congress of Tropical Medicine and International Health; EDCTP, European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP); IVC, International Vaccines Congress.

All searches were run on October 27, 2022, without placing any time or language restriction. Each data source listed above was screened by one co-author and subsequently checked by a second co-author; any conflicts were solved by discussion between co-authors.

Eligibility criteria

All phase 1, 2 or 3 trials involving human subjects, registered in at least one publicly available clinical trial database, and evaluating a vaccine candidate designed to prevent LASV infection or LF were eligible for inclusion regardless of their status (completed, active, recruiting, not yet recruiting, suspended, terminated, or other). Preclinical studies were not considered as they were outside the scope of our aims.

Data extraction and synthesis

After identifying all eligible clinical trials, we examined their registration information and other relevant details and extracted data using a standardized template created for this purpose (Microsoft Excel [Redmond, WA, USA]). For trials registered in two or more registries, we systematically compared available information from all sources; the most recently updated records were utilized in case of conflicting information (e.g., key trial dates). In the data extraction process, we focused on the following aspects: 1) characteristics of the vaccine candidate under investigation, 2) trial phase and aims, 3) eligibility criteria of the study population, 4) number and location of trial sites, 5) outcome measures of interest, and 6) sponsor and funding sources. All data were extracted by one co-author and checked for completeness and correctness by a second co-author; discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached.

We descriptively and qualitatively summarized the main features of each vaccine candidate and each trial identified, using tables and figures to compare the similarities and most important differences among the trials.

Based on the characteristics of the vaccine candidates under evaluation and the design of the clinical trials described in the trial registries, we assessed strengths, limitations, and challenges to the development of LF vaccines given the current LF vaccine development landscape.

RESULTS

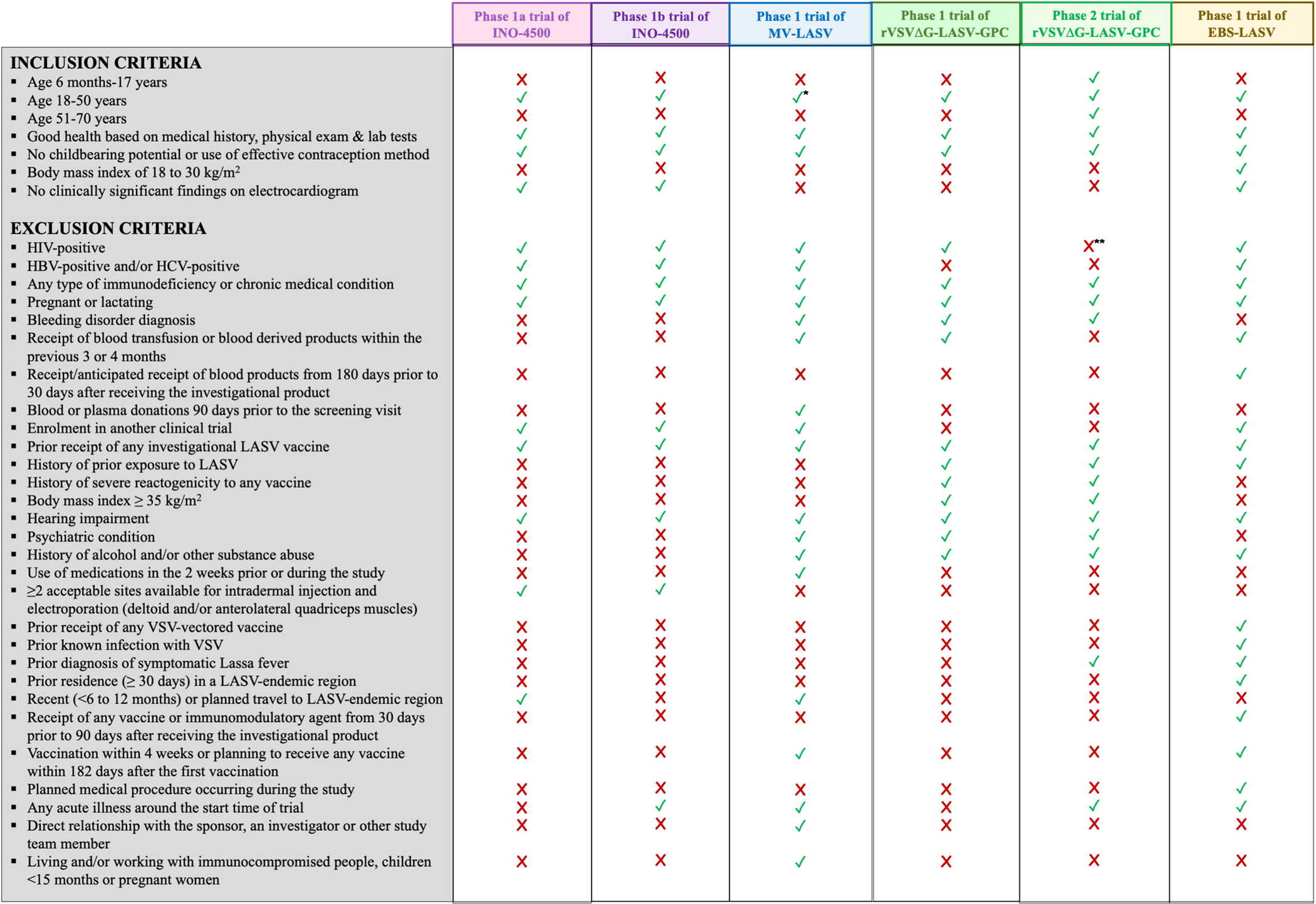

We identified four Lassa vaccine candidates for which at least one clinical trial (any phase) has been registered. We also found six registered clinical trials (five phase 1 and one phase 2), all funded by CEPI, that were designed to assess one of those vaccine candidates. The main characteristics of each vaccine candidate and trial are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Figure 1 provides a list of inclusion and exclusion criteria used to define participants’ eligibility in each of the six clinical trials.

Table 2:

Clinical trials evaluating Lassa fever vaccine candidates. Data were obtained by systematically searching 24 national and international trial registries as of October 27, 2022.

| Vaccine candidate under investigation | Clinical trial registration number (Registry) Trial title [Ref] |

Phase | Status | Start and completion dates of the study | Sponsor | Collaborator(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine candidate | Platform | Route of administration | Start | End | |||||

| INO-4500 | DNA-based | Intradermal injection followed by electroporation |

NCT03805984 (US CTR) Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of INO-4500 in Healthy Volunteers (46) |

1a | Recruitment completed | 9 May 2019 | 21 Oct 2020 | Inovio Pharmaceuticals | CEPI |

|

NCT04093076 (US CTR) Dose-Ranging Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of INO-4500 in Combination with Electroporation in Healthy Volunteers in Ghana (47) |

1b | Recruitment completed | 27 Jan 2021 | 27 Sep 2022 | |||||

| MV-LASV | Recombinant viral vector, based on the measles Schwarz virus strain | Intramuscular injection |

NCT04055454 (US CTR) A Randomized, Placebo-controlled Trial to Evaluate the Optimal Dose of MV-LASV, a New Vaccine Against LASSA Virus Infection, Regarding Safety, Tolerability & Immunogenicity in Healthy Volunteers Consisting of an Unblinded Dose Escalation & an Observer-blinded Treatment Phase (50) |

1 | Recruitment completed | 26 Sep 2019 | 15 Jan 2021 | Themis Bioscience GmbH | CEPI, Harmony Clinical Research, Assign Data Management and Biostatistics GmbH |

| rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC | Recombinant viral vectored vaccine, based on VSV | Intramuscular injection |

NCT04794218 (US CTR) and PACTR202106625781067 (PACTR) A Phase 1 Randomized, Double-blinded, Placebo-controlled, Dose-escalation Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC Vaccine in Adults in Good General Heath (52) and (53) |

1 | Recruiting | 23 Jun 2021 | 1 Jan 2024 (anticipated) | IAVI | George Washington University, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Redemption Hospital, East-West Medical Research Institute |

| PACTR202210840719552 (PACTR) A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC Vaccine in Adults and Children Residing in West Africa (54) |

2 | Not yet recruiting | 1 Aug 2023 (anticipated) | 15 Sep 2026 (anticipated) | IAVI | Not reported | |||

| EBS-LASV | Recombinant viral vector, based on VSV | Intramuscular injection | PACTR202108781239363 (PACTR) A Phase 1 Randomized, Blinded, Placebo Controlled, Dose-Escalation and Dosing Regimen Selection Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of rVSV-Vectored Lassa Virus Vaccine in Healthy Adults at Multiple Sites in West Africa (55) |

1 | Recruiting | 22 Aug 2022 | 30 Sep 2023 (anticipated) | Emergent BioSolutions Inc. | Not reported |

CEPI, Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovation; IAVI, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative; PACTR, Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry; US CTR, United States Clinical Trial Registry; VSV, Vesicular Stomatitis Virus

Table 3:

Main methodological characteristics of clinical trials evaluating Lassa fever vaccine candidates identified through systematic searches across 24 trial registries as of October 27, 2022. Publicly available information was utilized to determine each trial’s study design, number and location of trial recruitment sites, target number of participants, anticipated duration of follow-up, and primary and secondary outcome measures of interest.

| Trial (Registration number) | Blinding | Number of experimental groups | Number (timing) of vaccine doses | Randomization approach | Location (number) of trial site(s) | Target sample size | Duration of follow-up | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1a trial of INO-4500 (NCT03805984) |

Triple | 2 (to test different doses) | 2 (Day 0, Week 4) Group A received a single 1mg injection on each day, Group B received 2 consecutive 1mg injections on each day. |

Sequential assignment | United States (1) | 60 | 48 weeks |

Primary: ◾ Percentage of participants with AEs ◾ Percentage of participants with ISRs ◾ Incidence of AESI Secondary: ◾ Change from baseline in Antigen Specific Binding Antibody titers ◾ Change from baseline in LASV neutralizing antibody levels ◾ Change from baseline in Interferon-Gamma response magnitude |

| Phase 1b trial of INO-4500 (NCT04093076) |

Triple | 2 | 2 (Day 0, Week 4) Group A received a single 1mg injection on each day, Group B received 2 consecutive 1mg injections on each day. |

Parallel assignment | Ghana (1) | 220 | 48 weeks |

Primary: ◾ Number of participants with AEs ◾ Number of participants with ISRs ◾ Number of participants with AESI ◾ Change from baseline in Antigen Specific Binding Antibodies ◾ Change from baseline in LASV neutralizing antibodies ◾ Change from baseline in Interferon-Gamma response magnitude Secondary: None reported |

| Phase 1 trial of MV-LASV (NCT04055454) | Quadruple | 2 | 2 (Day 0, Day 28) | Parallel assignment | Belgium (1) | 60 | 12 months |

Primary: ◾ Rate of AEs Secondary: ◾ Rate of SAEs ◾ Evidence of LASV-specific cell-mediated immunity (i.e., presence of functional CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells) ◾ Level of anti-LASV antibodies ◾ Level of anti-LASV neutralizing antibodies ◾ Rate of abnormal laboratory parameters ◾ Magnitude of vaccine viral vector shedding in blood, urine, and saliva |

| Phase 1 trial of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC (NCT04794218 and PACTR202106625781067) |

Triple | 7 | 1 dose Doses differed across experimental groups (from 2×10^4 to 2×10^7 PFU) |

Permuted blocks | United States (3); Liberia (1) | 110 | 12 months |

Primary: ◾ Proportion of participants with Grade 3 or higher reactogenicity (i.e. solicited AEs) ◾ Proportion of participants with Grade 2 or higher unsolicited AEs ◾ Proportion of participants with SAEs ◾ Proportion of participants with AESI Secondary: ◾ Magnitude and duration of viral RNA in plasma by PCR ◾ Magnitude and duration of vaccine viremia by culture ◾ Magnitude and duration of viral RNA in urine and saliva by PCR ◾ Magnitude and duration of vaccine shedding in urine and saliva by culture |

| Phase 2 trial of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC (PACTR202210840719552) | Triple | 2 | 1 dose | Simple | Liberia (1) Nigeria (1) Ghana (1) |

612 | 6 months |

Primary: ◾ Proportion of participants with AEs ◾ Proportion of participants with SAEs ◾ Proportion of participants with AESI Secondary: ◾ Proportion of participants with binding antibody responses to LASV-GPC ◾ Magnitude of binding antibody responses to LASV-GPC ◾ Proportion of participants with neutralizing antibody responses against LASV ◾ Magnitude of neutralizing antibody responses against LASV vaccine distribution and shedding ◾ Magnitude and duration of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC vaccine viremia by culture ◾ Magnitude and duration of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC vaccine shedding in urine and saliva by culture ◾ Magnitude and duration of vaccine viral RNA in semen and cervicovaginal secretions by PCR ◾ Magnitude and duration of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC vaccine shedding in semen and cervicovaginal secretions by culture Immunogenicity |

| Phase 1 trial of EBS-LASV (PACTR202108781239363) | Double | 10 | 2 (Day 1, Day 29) or 4 (Day 1, Day 15, Day 29, Day 57), depending on the trial arm Multiple doses tested: from 1×10^5 to 1×10^7 PFU. |

Simple | Ghana (2) | 108 | 225 days |

Primary: ◾ Incidence of AEs, SAEs and AESI ◾ Incidence of rVSV viral shedding in blood, urine, and saliva ◾ Incidence of reactogenicity events and solicited systemic and injection site reactions Secondary: ◾ LASV neutralizing antibody levels ◾ LASV-GP-specific immunoglobulin G levels |

AE, Adverse Event; AESI, Adverse Event of Special Interest; GPC, Glycoprotein complex; ISR, Injection Site Reaction; LASV, Lassa Virus; PACTR, Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry; PCR, Polymerase Chain Reaction; PFU, Plaque forming units; rVSV, Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus; SAE, Serious Adverse Event; US CTR, United States Clinical Trial Registry.

Figure 1:

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants of the six registered clinical trials evaluating Lassa vaccine candidates retrieved through systematic searches of 24 trial registries as of October 27, 2022. Publicly available information has been used to compile the list of criteria and indicate whether each was implemented in a given trial.

* The age range of eligible participants for this trial is 18 to 55 years old.

** People living with HIV are considered eligible for a subset of the trial population provided that are stably on antiretroviral treatment, have a viral load of <50 copies/ml.

Abbreviations: HBV, Hepatitis B Virus; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; LASV, Lassa Virus; VSV, Vesicular Stomatitis Virus.

Lassa vaccine candidates in clinical trials

INO-4500

INO-4500 is a DNA-based vaccine encoding the LASV (Josiah strain) glycoprotein precursor (LASV GPC) gene (33). This vaccine, developed by Inovio Pharmaceuticals, is administered through intradermal injection, followed by electroporation using a minimally invasive device (CELLECTRA® 2000) which utilizes a brief electrical pulse to create small transient pores in the cell and enable the delivery of the vaccine into the cell itself (34, 35). This product does not require freezing in storage and transport.

MV-LASV

Based on a replicating, live-attenuated Schwarz strain measles virus vector, MV-LASV was developed by Themis Bioscience in collaboration with Institut Pasteur. This vaccine is designed to express the LASV glycoprotein and nucleoprotein antigens, is administered intramuscularly and has no freezing requirements (33). The measles virus was chosen as a vector as it can stably encode large genome segments and has been shown to contribute to a good immune response (36, 37, 38, 39).

rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC

rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC is a viral vector-based vaccine candidate jointly developed by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). This vaccine utilizes a recombinant form of the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus (rVSV) (i.e., the same platform used for the rVSV-vectored Ebola Zaire vaccine, ERVEBO®) to express the LASV glycoprotein (Josiah strain) (33), requires intramuscular administration and does not need to be frozen. VSV, which rarely infects humans and – when it does – generally produces an asymptomatic infection, has several advantages as a vaccine vector, such as the ability to potentially harbor large transgenes and the inability to integrate into the host genome (31, 33, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44).

EBS-LASV

EBS-LASV is also a VSV-based vaccine candidate encoding the LASV glycoproteins (Josiah strain), developed by Emergent BioSolutions Inc. It utilizes the VesiculoVax™ vector, which is similar to the rVSV vector included in IAVI’s vaccine, and is administered via intramuscular injection (31, 33, 45). Like the other vaccine candidates described above, this product does not have freezing requirements.

Clinical trials of Lassa vaccine candidates

Phase 1 trials of INO-4500

INO-4500 was the first LF vaccine candidate to advance to the clinical stage of assessment, with a phase 1a and a phase 1b trial registered thus far (46, 47). The phase 1a trial (NCT03805984) was conducted between May 2019 and October 2020 at a single site located in the United States (46). This trial adopted triple masking (participant, care provider, investigator) and used sequential assignment to determine whether participants would receive the active product or a placebo. Depending on the experimental group, participants received either one or two injections of 1 mg/dose on Day 0 and Week 4. This trial was designed to assess the safety and immunogenicity of INO-4500 with a planned sample size of 60 adult participants, whose eligibility criteria are summarized in Figure 1, to be followed up for 48 weeks. Of note, immunogenicity-related outcomes included both measures of antibody response and indicators of cell-mediated immunity. Preliminary findings from this phase 1a trial, shared with the scientific community at the 2021 edition of the International Vaccines Congress, suggest that two doses of INO-4500 administered four weeks apart are capable of eliciting a strong T cell response (48).

Inovio’s phase 1b trial (NCT04093076) began enrolling participants in January 2021, with recruitment taking place in one center in Ghana. In October 2021 the company announced the completion of enrolment, with 220 adults recruited as planned (49). According to the registration records, the phase 1a and 1b trials were fairly similar in terms of design, eligibility criteria of study participants, and outcome measures of interest. One key difference was that the phase 1a trial took place in a site where LF was not endemic, whereas the phase 1b trial took place in a setting where LF is endemic. Therefore, having recently travelled or having plans to travel to LASV-endemic areas was a cause for participants’ exclusion in the phase 1a trial, but not the phase 1b trial.

Phase 1 trial of MV-LASV

Themis Bioscience’s vaccine candidate, MV-LASV, was the second to enter clinical evaluation, with participant enrolment taking place between September 2019 and March 2020. The phase 1 trial (NCT04055454) (50), conducted at one site in Belgium with the primary aim of dose optimization, completed follow-up in January 2021. This quadruple-blind (participant, care provider, investigator, outcome assessor) trial was designed to recruit 60 adult participants who were randomized to receive two injections (on Day 0 and Day 28) of one of the following: low-dose vaccine (group A, n=24), high-dose vaccine (group B, n=24), or placebo (group C, n=12). Participants’ eligibility criteria for this trial included most of those listed for Inovio’s trials, but the upper age limit was slightly higher (18–55 versus 18–50 years) and additional exclusion criteria also applied (most notably those with a bleeding disorder and receipt/donation of blood products were ineligible). Besides assessing the vaccine’s safety profile (as is the case in any phase 1 clinical trials), the MV-LASV trial also aimed to evaluate the magnitude of humoral and cell-mediated responses, and – given the vaccine platform in use – measure the extent of viral vector shedding. To our knowledge, the results of this trial have not been published to date.

Phase 1 and 2 trials of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC

IAVI is the primary sponsor of the “Lassa Vaccine Efficacy and Prevention for West Africa” (LEAP4WA) project (51), which includes a series of clinical trials of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC.

The phase 1 trial (NCT04794218 and PACTR202106625781067) started enrolment in June 2021, with estimated completion of follow-up in January 2024, and comprises two steps: dose escalation (conducted across three sites in the United States) and dose group expansion (carried out in one site in Liberia) (51, 52, 53). This triple-blind (participant, care provider, investigator) trial makes use of permuted block randomization to assign participants to one of seven experimental groups or placebo, with all participants receiving a single dose on Day 1 with a follow-up of 12 months. All primary outcomes are safety-related, whereas secondary outcomes include the evaluation of the antibody response as well as various measures of vaccine shedding and viral RNA levels in bodily fluids. Most eligibility criteria align with those of the other LF vaccine phase 1 trials (Figure 1).

The phase 2 trial (PACTR202210840719552) is set to start recruiting a total of 612 individuals in August 2023 across three sites located in Liberia, Nigeria, and Ghana (54). In this triple-blind trial, simple randomization will be used to assign participants to receive the vaccine or placebo, and each of them will be followed-up for 6 months. The study population will include a wider range of individuals compared to phase 1 trials: most notably, the age range will be 18 months to 70 years, and a subset of participants will be people living with HIV who are receiving antiretroviral treatment and have a good enough viro-immunological profile (viral load < 50 copies/ml) (Figure 1). This trial is aimed at further examining the vaccine candidate’s safety profile (primary outcome) and evaluating humoral immune responses (secondary outcomes) in a broader and more heterogenous population relative to earlier phase trials.

Phase 1 trial of EBS-LASV

Emergent Biosolutions’ trial of EBS-LASV (PACTR202108781239363) (55), began recruitment in August 2022 at two sites in Ghana, with estimated completion of follow-up in September 2023. This double-blind (care provider, participant) trial has a target sample size of 108 adult participants, to be assigned to one of 10 experimental groups or placebo through simple randomization. Depending on the trial arm, each participant will receive either two doses (on Days 1 and 29) or four doses (on Days 1, 15, 29 and 57) of the active product or placebo. This trial is mainly focused on dose escalation and dose selection, with safety and vaccine viral shedding as primary outcomes, and humoral response indicators as secondary outcomes. Participants’ eligibility criteria align with those of most other Lassa vaccine trials; notably, “prior residence, any time in the past, greater than 30 days in a LASV-endemic region (as per latest available WHO data)” constitutes an exclusion criterion for this trial even if the country of recruitment is Ghana (55).

DISCUSSION

The unprecedented resource mobilization observed over the past few years, and particularly CEPI’s substantial investments, has led to significant advancements in Lassa vaccine development research, with four vaccine candidates entering clinical trials in the past three years after decades of preclinical studies. Five phase 1 trials and one phase 2 trial of LF vaccine candidates have been registered thus far and are currently at various stages of advancement. Much of this change of pace can be ascribed to the establishment of the WHO’s priority disease list, including a range of emerging and re-emerging viruses of concern such as LASV (14, 16). Besides the chronic lack of funding that Lassa vaccine research has suffered until recently, developing and evaluating successful vaccine candidates against LASV infection and/or LF are fraught with challenges.

An ideal vaccine candidate should align with the WHO’s target product profile (TPP) to ensure that a vaccine for preventive use is safe and efficacious, especially in target populations, such as healthcare workers, or other high-risk individuals, such as pregnant and immunocompromised individuals, in LASV-endemic areas. Additionally, a vaccine candidate should ideally provide long-term protection with a single-dose regimen, given the geographical considerations and constrained resources of the target population. The WHO TPP for Lassa vaccines, first released in 2017, details minimal and preferred vaccine characteristics regarding the target population, safety, efficacy, dose regimen, duration of protection, route of administration, coverage, as well as product stability and storage (56).

In keeping with the WHO TPP, none of the Lassa vaccine candidates that are currently being tested in clinical trials require freezing. Nonetheless, these vaccines are based on highly sophisticated technologies, which may pose manufacturing difficulties in low- and middle-income countries unless proper efforts are made to build capacity locally and ensure transfer of technology (57). Also, while three of four candidates use a route of administration recommended by the TPP, INO-4500 (which is DNA-based) requires electroporation post-injection to ensure cell penetration and optimize the response. While this procedure may complicate deployment, DNA-based vaccines have many advantages, such as their stability and the relative ease and low cost of large-scale manufacturing (58).

Notably, all four Lassa vaccine candidates that have entered clinical trials are on track to meet WHO’s recommendation of not exceeding a 3-dose regimen for primary vaccination series (56). rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC is designed for a single-dose regimen, making it an ideal candidate for use in a non-emergency setting, in addition to allowing rapid mass vaccination and facilitation of stockpiling during an active outbreak. All other vaccine candidates are being evaluated as a two-dose series, administered approximately four weeks apart, though a four-dose regimen is also being tested for the EBS-LASV vaccine.

We found that the six registered clinical trials are taking place in one to four sites located in one or more of four LASV-endemic countries (Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone) and/or two non-endemic countries (Belgium, United States). Individuals in non-endemic areas are more likely to be immunologically naïve, thus facilitating a clear interpretation of results as immunologic history does not need to be considered. It is important to expand recruitment to sites located in endemic areas to ensure that safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy data are collected from populations who would benefit most from a LF vaccine.

All phase 1 trials described in this review only involve healthy adults aged 18 to 50 or 55 years and share several other inclusion and exclusion criteria, most of which fall within standard requirements for early-stage clinical trials. However, as certain population groups such as pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, children/adolescents, and older adults have a disproportionately higher risk of severe and fatal LF, efforts should be made to evaluate safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of vaccine candidates in these subgroups as early as possible. The only phase 2 Lassa vaccine trial that has been registered thus far will enrol a broader population, including children as young as 18 months old, adults up to age 70 years, and people living with HIV who meet specific conditions, though pregnant women remain excluded.

Participants’ follow-up duration ranges between 225 days and 12 months across the five phase 1 trials, whereas individuals recruited in the phase 2 trial will be followed up for 6 months. As vaccine candidates progress through more advanced phases of clinical evaluation, considerable planning will be required to design and implement gold-standard large-scale efficacy trials, but prioritizing validation of immunological surrogate endpoints could overcome many of the challenges that efficacy trials face (59). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the traditionally lengthy timelines of vaccine trial recruitment and follow-up were significantly accelerated, and this acceleration will continue to be important for vaccines against other emerging and re-emerging diseases of pandemic potential (60, 61).

This work provides an overview of the current Lassa vaccine development landscape, with a focus on vaccine candidates that have already entered the clinical phase of assessment. For this purpose, we conducted a thorough and comprehensive review utilizing rigorous methods to search and extract data about each vaccine candidate and each trial from a range of sources. However, as we did not have access to the full trial protocols and could only rely on publicly available data, relevant details pertaining to the trials’ plans and characteristics may be incomplete and trial registries may not be up to date. Making trial protocols publicly accessible could ensure greater transparency in the future.

With four LF vaccine candidates currently undergoing clinical testing with CEPI’s financial support, progress towards a safe and effective LF vaccine is encouraging though still in early stages. Continued efforts are necessary to ensure that a safe and effective Lassa vaccine becomes available for use in the near future. Such a vaccine would not only have the potential to significantly reduce the burden of disease attributable to LASV with immediate benefits for those living in endemic areas, but could also contribute to reducing the risk of an ensuing pandemic, constituting an important tool for global LASV prevention and control. Comparing and contrasting each of the LF vaccine candidates as they advance through phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials can provide important insight into the scope of the LF vaccine development landscape and highlight opportunities for accelerating and diversifying efforts.

Funding

This work was supported by research funds from the Canada Research Chair (CRC) program (https://www.chairs-chaires.gc.ca/program-programme/index-eng.aspx) [PI: Nicole E. Basta, CRC in Infectious Disease Prevention (Tier 2)]. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (https://www.niaid.nih.gov) under Award Number R01AI132496 (PI: Dr. Nicole E. Basta). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.McCormick JB, King IJ, Webb PA, Johnson KM, O’Sullivan R, Smith ES, et al. A case-control study of the clinical diagnosis and course of Lassa fever. J Infect Dis. 1987;155(3):445–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basinski AJ, Fichet-Calvet E, Sjodin AR, Varrelman TJ, Remien CH, Layman NC, et al. Bridging the gap: Using reservoir ecology and human serosurveys to estimate Lassa virus spillover in West Africa. PLoS Comput Biol. 2021;17(3):e1008811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lecompte E, Fichet-Calvet E, Daffis S, Koulémou K, Sylla O, Kourouma F, et al. Mastomys natalensis and Lassa fever, West Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1971–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Lassa fever. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;262:75–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner BM, Safronetz D, Stein DR. Current research for a vaccine against Lassa hemorrhagic fever virus. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:2519–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilori EA, Frank C, Dan-Nwafor CC, Ipadeola O, Krings A, Ukponu W, et al. Increase in Lassa Fever Cases in Nigeria, January-March 2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(5):1026–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uwishema O, Alshareif BAA, Yousif MYE, Omer MEA, Sablay ALR, Tariq R, et al. Lassa fever amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: A rising concern, efforts, challenges, and future recommendations. J Med Virol. 2021;93(12):6433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Price ME, Fisher-Hoch SP, Craven RB, McCormick JB. A prospective study of maternal and fetal outcome in acute Lassa fever infection during pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297(6648):584–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richmond JK, Baglole DJ. Lassa fever: epidemiology, clinical features, and social consequences. BMJ. 2003;327(7426):1271–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao BS, Byl FM, Adour KK. Audiometric Comparison of Lassa Fever Hearing Loss and Idiopathic Sudden Hearing Loss: Evidence for Viral Cause. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 1992;106(3):226–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ezeomah C, Adoga A, Ihekweazu C, Paessler S, Cisneros I, Tomori O, et al. Sequelae of Lassa Fever: Postviral Cerebellar Ataxia. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ficenec SC, Percak J, Arguello S, Bays A, Goba A, Gbakie M, et al. Lassa Fever Induced Hearing Loss: The Neglected Disability of Hemorrhagic Fever. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;100:82–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogbu O, Ajuluchukwu E, Uneke CJ. Lassa fever in West African sub-region: an overview. J Vector Borne Dis. 2007;44(1):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization (WHO). An R&D Blueprint for Action to Prevent Epidemics: Plan of Action 2016. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (WHO); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouglas D, Christodoulou M, Plotkin SA, Hatchett R. CEPI: Driving Progress Toward Epidemic Preparedness and Response. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2019;41(1):28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.CEPI: Priority diseases: Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI); 2022. [Available from: https://cepi.net/research_dev/priority-diseases/.

- 17.Formenti B, Gregori N, Crosato V, Marchese V, Tomasoni LR, Castelli F. The impact of COVID-19 on communicable and non-communicable diseases in Africa: a narrative review. Infez Med. 2022;30(1):30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevalie S, Youkee D, van Duinen AJ, Bailey E, Bangura T, Mangipudi S, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital utilisation in Sierra Leone. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(10):e005988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onchonga D, Alfatafta H, Ngetich E, Makunda W. Health-seeking behaviour among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Heliyon. 2021;7(9):e07972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Global community comes together in support of 100 Days Mission and pledges over $1.5 billion for CEPI’s pandemic-busting plan [press release]. Oslo, Norway: Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI)2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asogun DA, Günther S, Akpede GO, Ihekweazu C, Zumla A. Lassa Fever: Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Management and Prevention. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 2019;33(4):933–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redding DW, Gibb R, Dan-Nwafor CC, Ilori EA, Yashe RU, Oladele SH, et al. Geographical drivers and climate-linked dynamics of Lassa fever in Nigeria. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klitting R, Kafetzopoulou LE, Thiery W, Dudas G, Gryseels S, Kotamarthi A, et al. Predicting the evolution of the Lassa virus endemic area and population at risk over the next decades. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiley MP, Lange JV, Johnson KM. Protection of rhesus monkeys from Lassa virus by immunisation with closely related Arenavirus. Lancet. 1979;2(8145):738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen MD, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Hustad HL, Bausch DG, Demby AH, et al. Genetic Diversity among Lassa Virus Strains. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(15):6992–7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siddle KJ, Eromon P, Barnes KG, Mehta S, Oguzie JU, Odia I, et al. Genomic Analysis of Lassa Virus during an Increase in Cases in Nigeria in 2018. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;379(18):1745–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garry RF. Lassa fever - the road ahead. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21(2):87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiley MR, Fakoli L, Letizia AG, Welch SR, Ladner JT, Prieto K, et al. Lassa virus circulating in Liberia: a retrospective genomic characterisation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(12):1371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy H, Ly H. Understanding Immune Responses to Lassa Virus Infection and to Its Candidate Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallam HJ, Hallam S, Rodriguez SE, Barrett ADT, Beasley DWC, Chua A, et al. Baseline mapping of Lassa fever virology, epidemiology and vaccine research and development. npj Vaccines. 2018;3(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salami K, Gouglas D, Schmaljohn C, Saville M, Tornieporth N. A review of Lassa fever vaccine candidates. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;37:105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukashevich IS. The search for animal models for Lassa fever vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2013;12(1):71–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Purushotham J, Lambe T, Gilbert SC. Vaccine platforms for the prevention of Lassa fever. Immunol Lett. 2019;215:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diehl MC, Lee JC, Daniels SE, Tebas P, Khan AS, Giffear M, et al. Tolerability of intramuscular and intradermal delivery by CELLECTRA(®) adaptive constant current electroporation device in healthy volunteers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(10):2246–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin F, Shen X, Kichaev G, Mendoza JM, Yang M, Armendi P, et al. Optimization of electroporation-enhanced intradermal delivery of DNA vaccine using a minimally invasive surface device. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2012;23(3):157–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mühlebach MD. Vaccine platform recombinant measles virus. Virus Genes. 2017;53(5):733–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tschismarov R, Van Damme P, Germain C, De Coster I, Mateo M, Reynard S, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of a recombinant measles-vectored Lassa fever vaccine: a randomised, placebo-controlled, first-in-human trial. Lancet. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mateo M, Reynard S, Pietrosemoli N, Perthame E, Journeaux A, Noy K, et al. Rapid protection induced by a single-shot Lassa vaccine in male cynomolgus monkeys. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okokhere PO. Finding a safe and effective vaccine for the Lassa virus. Lancet. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fathi A, Dahlke C, Addo MM. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vector vaccines for WHO blueprint priority pathogens. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(10):2269–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tober R, Banki Z, Egerer L, Muik A, Behmüller S, Kreppel F, et al. VSV-GP: a potent viral vaccine vector that boosts the immune response upon repeated applications. J Virol. 2014;88(9):4897–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geisbert TW, Jones S, Fritz EA, Shurtleff AC, Geisbert JB, Liebscher R, et al. Development of a new vaccine for the prevention of Lassa fever. PLoS Med. 2005;2(6):e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safronetz D, Mire C, Rosenke K, Feldmann F, Haddock E, Geisbert T, et al. A recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus-based Lassa fever vaccine protects guinea pigs and macaques against challenge with geographically and genetically distinct Lassa viruses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(4):e0003736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cross RW, Woolsey C, Prasad AN, Borisevich V, Agans KN, Deer DJ, et al. A recombinant VSV-vectored vaccine rapidly protects nonhuman primates against heterologous lethal Lassa fever. Cell Rep. 2022;40(3):111094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cross RW, Xu R, Matassov D, Hamm S, Latham TE, Gerardi CS, et al. Quadrivalent VesiculoVax vaccine protects nonhuman primates from viral-induced hemorrhagic fever and death. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):539–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of INO-4500 in Healthy Volunteers (Identifier: NCT03805984): US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov; 2019. [Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03805984?cond=lassa&draw=2&rank=8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dose-ranging Study: Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of INO-4500 in Healthy Volunteers in Ghana (Identifier: NCT04093076): US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov; 2019. [Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04093076?cond=lassa&draw=2&rank=7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marrero I INO 4500, a DNA based LASV vaccine, induces robust T cell responses and long-term memory antigen-specific T cells. International Vaccines Congress (IVC); Orlando, USA (hybrid event) 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Press release: INOVIO Completes Enrollment of Phase 1B Clinical Trial for its DNA Vaccine Candidate Against Lassa Fever, INO-4500, in West Africa [October 26, 2021] [press release]. Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc.2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.A Trial to Evaluate the Optimal Dose of MV-LASV (V182–001) (Identifier: NCT04055454): US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov; 2019. [Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04055454?term=NCT04055454&draw=1&rank=1. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gupta S, Fast P, Lehrman J, Price M. Lassa Fever Vaccine Efficacy and Prevention For West Africa (LEAP4WA). 10th EDCTP Forum; Maputo, Mozambique; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 52.A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC Vaccine in Adults in Good General Heath (Identifier: NCT04794218): US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov; 2021. [Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04794218?cond=lassa&draw=2&rank=9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.A Phase 1 Randomized, Double-blinded, Placebo-controlled, Dose-escalation Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC Vaccine in Adults in Good General Health (Identifier: PACTR202106625781067): Pan African Clinical Trial Registry; 2021. [Available from: https://pactr.samrc.ac.za/TrialDisplay.aspx?TrialID=15920.

- 54.Pan African Clinical Trial Registry. A Phase 2 Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Immunogenicity of rVSVΔG-LASV-GPC Vaccine in Adults and Children Residing in West Africa. (Identifier: PACTR202210840719552) 2022. [Available from: https://pactr.samrc.ac.za/TrialDisplay.aspx?TrialID=23666.

- 55.A study to assess a new Lassa Virus Vaccine in healthy volunteers (Identifier: PACTR202108781239363): Pan African Clinical Trial Registry; 2021. [Available from: https://pactr.samrc.ac.za/TrialDisplay.aspx?TrialID=14618.

- 56.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Target Product Profile for Lassa virus Vaccine. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khan MI, Ikram A, Hamza HB. Vaccine manufacturing capacity in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(7):479–a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee J, Arun Kumar S, Jhan YY, Bishop CJ. Engineering DNA vaccines against infectious diseases. Acta Biomater. 2018;80:31–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jin P, Li J, Pan H, Wu Y, Zhu F. Immunological surrogate endpoints of COVID-2019 vaccines: the evidence we have versus the evidence we need. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lurie N, Saville M, Hatchett R, Halton J. Developing Covid-19 Vaccines at Pandemic Speed. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1969–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plotkin S, Robinson JM, Cunningham G, Iqbal R, Larsen S. The complexity and cost of vaccine manufacturing – An overview. Vaccine. 2017;35(33):4064–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]