Abstract

Purpose

We describe the management of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome in monozygotic female twins with congenital cataracts, exudative retinal detachments, and one case of corneal descemetocele with associated dellen and subsequent perforation.

Methods

Case report and review of the literature.

Results

Twins 1 and 2 exhibited all seven cardinal characteristics of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome, presenting with spontaneous lenticular resorption, anterior uveitis, and glaucoma. They underwent bilateral cataract extraction with near total capsulectomy. Both twins experienced recurrent glaucoma, for which Twin 1 underwent successful endocyclophotocoagulation in both eyes and Twin 2 in the left eye only. The fellow eye developed two sites of perilimbal corneal descemetoceles with associated dellen at the inferotemporal limbal corneal junction leading to spontaneous perforation of one site, requiring a full thickness corneal graft. Both twins developed recurrent bilateral exudative retinal detachments unresponsive to oral prednisolone. Twin 1’s last best corrected visual acuity with aphakic spectacles was 20/260 right eye and 20/130 left eye at age 4 years and 8 months. Twin 2’s last best corrected visual acuity was 20/130 in each eye at age 4 years and 11 months, over a year following right eye penetrating keratoplasty.

Conclusions

We describe two rare cases of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome in monozygotic twins complicated by corneal perforation requiring penetrating keratoplasty in one eye of one twin. Although corneal opacities have been described in this condition, this is the first case of corneal descemetocele in Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome. The cornea was stabilized with a relatively favorable visual outcome over one year later.

Keywords: Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome, corneal perforation, keratoplasty, descemetocele, congenital cataracts, monozygotic twins

Introduction

Hallermann-Streiff syndrome (OMIM 234100) is a rare congenital disease with fewer than 200 cases reported worldwide.1 The seven cardinal features of Hallermann-Streiff syndrome include ocular findings (bilateral microphthalmia and congenital cataracts) and characteristic facial appearance (micrognathia, proportionate short stature, hypotrichosis, dyscephaly, and beaked nose).1 Challenging management of chronic uveitis, glaucoma, exudative retinal detachments, and spontaneously resorbing cataracts have been described in isolated case reports in the literature.2-4 One study found corneal opacities in 5 of 6 Hallermann-Streiff syndrome patients.5 Nonetheless, management of corneal disease for this condition is rarely mentioned. This report includes two monozygotic twins with Hallermann-Streiff syndrome with one case of corneal descemetocele with associated dellen and spontaneous perforation necessitating penetrating keratoplasty.

Case Report

Twins 1 and 2 were monozygotic female twins born at 32 weeks gestation, referred for a retinopathy of prematurity exam at four weeks. Family history was negative for congenital ocular disease or craniofacial abnormalities (Figure 1). Parents were of Filipino heritage. Pregnancy and delivery were unremarkable. Both twins had a normal chromosome microarray. Parents declined further genetic testing. They were both found to have all seven cardinal features of Hallermann-Streiff syndrome (Figure 2A-C)1 along with small palpebral fissures, anterior capsular pigment, and elongated ciliary body processes. Twin 1 underwent a tracheotomy at 3 months of age due to severe central sleep apnea. Twin 2 ultimately required this at 10 months of age. Both twins had developmental delays, likely exacerbated by early hearing loss, airway obstruction, and ocular disease. After years of therapy, they both demonstrated improved gross motor skills with persistent delays in expressive and receptive language at last follow up.

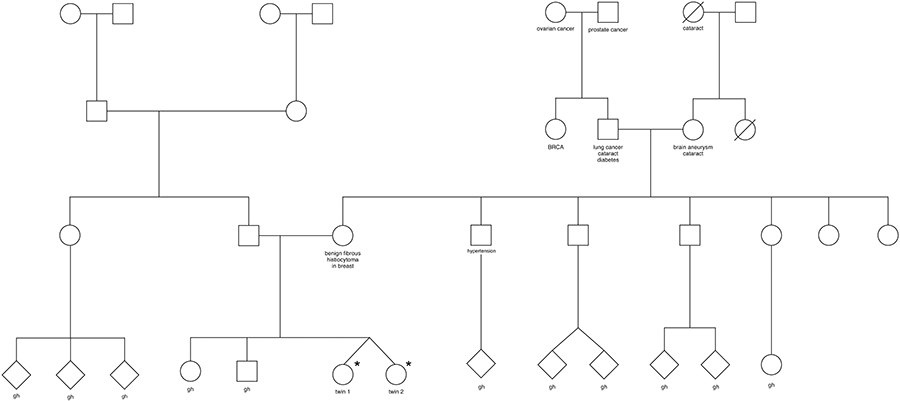

Figure 1.

Family pedigree. *Affected twins. gh=good health.

Figure 2.

Microphthalmia, small palpebral fissures, and sparse eyelash and eyebrow hair in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Twin 1 at 17 months of age from the (A) front and (B) side view. (C) Twin 2 at three years of age with corneal descemetocele in the right eye. (D) Color fundus photos of the right eye and (E) the left eye of Twin 1 at 23 months showing bilateral exudative retinal detachments involving the macula with hyperemic optic nerves. Twin 2 had similar fundus findings. (F) Corneal descemetocele at the limbus in the right eye of Twin 2 at 3.5 years. The patient went on to corneal perforation one year later.

TWIN ONE

Born 1511 grams, Twin 1 developed spontaneous resorption of bilateral congenital cataracts, ocular hypertension at two months (30 mmHg in the right eye and 28 mmHg in the left eye by tonopen), and progressive posterior synechiae necessitating treatment with topical timolol 0.25%, prednisolone 1%, and atropine 1%. At three months, she developed bilateral iris bombe configuration but flat retinas on B-scan. Bilateral cataract extraction with near-total capsulectomy resulted in normalized intraocular pressures off timolol. She was started on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day for one week postoperatively.

At seven months, the patient developed waxing and waning bilateral exudative retinal detachments that became persistent by 19 months. At two years, ocular hypertension recurred (30’s in both eyes by iCare), prompting the initiation of cosopt and latanoprost. Slit lamp examination revealed bilateral 2+ flare with progressive posterior synechiae, therefore 0.3 mg/kg oral prednisolone was started.

At 2.5 years, tonopen intraocular pressures were 32 in the right eye and 19 in the left eye. Corneal diameters were 7.75mm and 7mm, and axial lengths were 10mm and 9mm by A-scan, respectively. Cycloplegic refraction was stable at +36.00 sphere in the right eye and +38.00 sphere in the left eye. Fundus examination revealed bilateral large, bullous exudative retinal detachments and pink, hyperemic optic nerves without obvious cupping (Figure 2D-E). She failed maximum glaucoma medical therapy, including oral acetazolamide, and therefore underwent endocyclophotocoagulation for six clock hours in both eyes. The last follow-up at 4 years and 8 months demonstrated a best corrected visual acuity by Teller acuity with aphakic spectacles of 20/260 right eye and 20/130 left eye, with persistent nystagmus.

TWIN TWO

Born 1259 grams with bilateral congenital cataracts, Twin 2’s tonopen intraocular pressures were 24 and 32 in the right and left eyes at seven weeks, with bilateral posterior synechiae and a flat left anterior chamber. Topical timolol and prednisolone 1% were initiated in both eyes and dorzolamide in the left. By eight weeks, the cataracts started to resorb, alleviating the angle closure. However, ocular hypertension continued, requiring the addition of left eye apraclonidine and oral acetazolamide. At four months, no lens material was seen in either eye and the posterior capsule was absent in the left eye. Due to an airway complication, near-total bilateral capsulotomy was delayed until eight months.

One week postoperatively, Twin 2 developed a left serous retinal detachment despite oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day. Oral prednisolone was continued for one more week without improvement. During this period, intraocular pressures spiked to 35 and 40 in the right and left eyes, attributed to steroid-response glaucoma. The retinal detachment regressed over six months on topical steroids. Intraocular pressures normalized once steroids were discontinued.

At eight months, bilateral, large, macula-involving exudative retinal detachments recurred. Topical steroid was initiated but ultimately discontinued due to recurrent intraocular pressure spikes. At this time, corneal descemetocele with associated dellen developed in the right eye at the inferotemporal limbal corneal junction. At 12 months, a cooperative slit lamp examination revealed no cells in either eye and 2+ flare in the left eye. At two years, the patient had 1-2+ flare in both eyes with 3 cells per high-powered field in the left eye; therefore, bilateral once daily prednisolone 1% was initiated. At age three, a second area of limbal corneal descemetocele presented superotemporally in the right eye. Left intraocular pressure remained high (30’s) despite maximum medical management, including oral acetazolamide. Therefore, she underwent left eye endocyclophotocoagulation for six clock hours. Scleral friability was noted when closing the corneoscleral wound. Intraocular pressure remained at 16 in the left eye at 10 months postoperatively. At that time, the right eye’s inferotemporal corneal descemetocele with associated dellen spontaneously perforated, requiring a focal therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty. In the presence of ongoing nystagmus, final best corrected visual acuity with aphakic spectacles was 20/130 in each eye at age 4 years and 11 months (1 year and 3 months following right eye penetrating keratoplasty).

Discussion

We report the second account of concordant monozygotic twins with presumptive Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome1 and the first case of corneal descemetocele in the setting of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome. This corneal change led to dellen and perforation without underlying elevated intraocular pressure or corneal exposure at the time of perforation. Despite next-generation sequencing technologies, the underlying cause of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome remains unknown.6

Both twins had a normal chromosome microarray. Despite genetic counseling, the parents declined further genetic testing. However, both twins exhibited all seven cardinal features of Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome, and therefore met criteria for a clinical diagnosis of Hallermann-Streiff. Nonetheless, a differential diagnosis must be considered given lack of molecular confirmation. Other diagnoses to consider include Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, Seckel syndrome, and Fanconi anemia, however none of these conditions have been reported to include the unusual ophthalmic conditions seen in both twins that are typical for Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome: microphthalmia, congenital cataracts with spontaneous resorption, uveitis, glaucoma, and exudative retinal detachments.

As previously described in Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome,4 both twins developed cataracts that eventually liquefied and spontaneously resorbed. However, withholding cataract extraction is thought to contribute to subsequent iridocyclitis and glaucoma by leaving a lenticular and capsular inflammatory nidus.4 We therefore elected to perform lensectomy and near total capsulectomy for both twins, with improved uveitis and glaucoma. The corneal limbal wounds may have contributed to later descemetocele in twin 2.

After cataract extraction, both twins were treated with oral prednisolone 1mg/kg/day for a week. Twin 2 developed steroid response glaucoma, and twin 1 did not. This was likely due to the delayed time to surgery for twin 2 compared to twin 1, possibly contributing to prolonged inflammation and glaucoma.

In twin 2, corneal descemetocele developed inferotemporally soon after intraocular pressure spikes at 8 months and superotemporally at 3 years in the right eye despite controlled intraocular pressures for over 2 years. There were no signs of corneal ulcer leading up to the descemetocele formation. Histologic and histochemical examination of skin in Hallermann-Streiff patients previously revealed abnormal scleral collagen, lack of cohesion, and global diminution of glycosaminoglycans with inadequate sulfation.7 An additional study examined the sclera in patients with Hallermann-Streiff syndrome using transmission electron microscopy, identifying frayed collagen fibers.8 These malformations may contribute to corneal abnormalities, particularly at the cornea-scleral interface. Nonetheless, corneal abnormalities in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome that require penetrating keratoplasty are rare. One report identified sclerocornea with this condition leading to an intraocular pressure of 45 mm Hg with associated corneal ectasia.9 That patient underwent penetrating keratoplasty. Another Hallermann-Streiff patient born with eyelid colobomas developed a corneal ulcer and later perforation necessitating penetrating keratoplasty as well.10

Twin 2 had an early clinical course of recurrent glaucoma in both eyes and was right hand-dominant with frequent eye rubbing (for unclear reasons), possibly both contributing to progressive thinning of vulnerable keratocytes due to Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. In spite of well-controlled intraocular pressures for over two years, these chronic changes may have resulted in progressive corneal descemetocele at two locations in the right eye, with dellen and spontaneous perforation at one location. Chronic topical prednisolone 1% used to treat persistent uveitis may have also contributed to progressive stromal thinning (of note, this was not given to the other twin, who did not develop these corneal changes). A focal therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was performed.

Both eyes of both twins had large recurrent exudative retinal detachments, well-described in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome.3 Nonetheless, at final follow-up visit at 4 years and 11 months, the penetrating keratoplasty allowed stability of the right cornea in twin 2, with a relatively favorable visual outcome of 20/130 in each eye, similar to that of twin 1.

Early recognition of Hallermann-Streiff syndrome allows for interventions that can reduce the severity of ophthalmic complications. It is important, when possible, to elicit a detailed family history and obtain genetic screening, along with evaluating for ophthalmic and systemic associations. Visual rehabilitation can be challenging due to unusually high refractive error along with steep corneas in the setting of microphthalmia and aphakia with chronic retinal detachments. In addition, patients with Hallermann-Streiff syndrome often need speech therapy, hearing aids, careful monitoring of the airway, and additional developmental support and medical evaluation. A multidisciplinary team both within and outside of ophthalmology is required to provide the most effective care for this condition.

These cases illustrate the challenging medical and surgical management of this complex syndrome, and aspects of the disease that impact the cornea. Although these children still have functional vision at 4 years of age, long-term visual prognosis remains guarded.

Conflicts of interest and Source of Funding:

All authors declare no conflict of interest. This research is funded in part by an NIH CORE grant and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness both to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Washington. Dr. Bly was supported through the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Research Integration Hub, Pilot Awards Support Fund Program.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Cohen MM. Hallermann-Streiff syndrome: A review. In: American Journal of Medical Genetics. Vol 41.; 1991. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins DJ, Horan EC. Glaucoma in the Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1970;54(6). doi: 10.1136/bjo.54.6.416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishina S, Suzuki Y, Azuma N. Exudative retinal detachment following cataract surgery in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2008;246(3):453–455. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0741-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolter JR, Jones DH. Spontaneous cataract absorption in Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Ophthalmologica Journal international d’ophtalmologie International journal of ophthalmology Zeitschrift für Augenheilkunde. 1965;150(6). doi: 10.1159/000304868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roulez FM, Schuil J, Meire FM. Corneal opacities in the Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Ophthalmic Genetics. 2008;29(2). doi: 10.1080/13816810802027101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt J, Wollnik B. Hallermann–Streiff syndrome: A missing molecular link for a highly recognizable syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2018;178(4). doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francois J. The Francois Dyscephalic Syndrome and Skin Manifestations.; 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart D, Streeten BW, Brockhurst RJ, Anderson DR, Hirose T, Gass J. Abnormal Scleral Collagen in Nanophthalmos. Vol 109.; 1991. https://jamanetwork.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schanzlin DJ. Article Title: Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome Associated with Sclerocornea, Aniridia, and a Chromosomal Abnormality.; 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spoerl GH, Romano PE. Penetrating Keratoplasty in a Complicated Mandibulo-OculoFacial Dyscephaly. Vol 10. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus; 1973. [Google Scholar]