Abstract

Objective

Many individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder (ED) have been exposed to traumatic events, and some of these individuals are diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although theorized by researchers and clinicians, it is unclear whether traumatic event exposure or PTSD interferes with outcomes from ED treatment. The objective of the current study was to systematically review the literature on traumatic events and/or PTSD as either predictors or moderators of psychological treatment outcomes in EDs.

Method

A PRISMA search was conducted to identify studies that assessed the longitudinal association between traumatic events or PTSD and ED outcomes. Eighteen articles met the inclusion criteria for review.

Results

Results indicated that traumatic event exposure was associated with greater ED treatment dropout, but individuals with a traumatic event history benefited from treatment similarly to their unexposed peers. Findings also indicated that traumatic events may be associated with greater symptom relapse post-treatment.

Discussion

Given the limited number of studies examining PTSD, results are considered very tentative; however, similar to studies comparing trauma-exposed and non-trauma-exposed participants, individuals with PTSD may have similar treatment gains compared to individuals without PTSD, but individuals with PTSD may experience greater symptom relapse post-treatment. Future researchers are encouraged to examine whether trauma-informed care or integrated treatment for eating disorders and PTSD mitigates dropout from treatment and improves symptom remission outcomes. Furthermore, researchers are encouraged to examine how the developmental timing of traumatic events, self-perceived impact of trauma, and cumulative trauma exposure may be associated with differential ED treatment outcomes.

Keywords: Eating disorders, Trauma, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Treatment outcome, Systematic Review

1. INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses with significant life-threatening medical and psychiatric morbidity and lower quality of life (Ágh et al., 2016; Arcelus et al., 2011; Klump et al., 2009; J. E. Mitchell & Crow, 2006). The remission rate for individuals undergoing eating disorder treatment varies between 30 and 50% (Atwood & Friedman, 2020), meaning that a large percentage of individuals that undergo treatment do not adequately respond. Psychiatric comorbidity in general is associated with poorer treatment outcomes from eating disorders (Vall & Wade, 2015), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and symptoms associated with traumatic events may interfere with the efficacy of eating disorder treatment (Brewerton, 2007). Estimates of traumatic event exposure vary widely, such that approximately 18–100% of individuals diagnosed with an eating disorder have been exposed to a traumatic event according to the DSM-5 PTSD criterion A definition (Backholm et al., 2013; Kjaersdam Telléus et al., 2021; K. S. Mitchell et al., 2012; Swinbourne et al., 2012). In samples of individuals with an eating disorder, a recent systematic review determined that pooled prevalence estimates of both current and lifetime PTSD were 18.35% when weighted by sample size and 24.59% when weighted by methodological quality, although these estimates may be higher in inpatient settings compared to outpatient settings (Ferrell et al., 2022). Traumatic event exposure and PTSD are therefore not uncommon in eating disorder populations.

Previous systematic reviews have found that childhood traumatic events (Caslini et al., 2016; Kimber et al., 2017; Molendijk et al., 2017; Pignatelli et al., 2017) and sexual assault (Chen et al., 2010; Madowitz et al., 2015; Smolak & Murnen, 2002) are associated with a higher likelihood of eating disorder diagnosis. Exposure to traumatic events and/or a diagnosis of PTSD is also associated with more severe psychopathology in individuals with eating disorders, such as greater eating, depressive, and anxiety symptoms as compared to individuals who have not been exposed to traumatic events (Backholm et al., 2013; Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, & Smith, 2021). Similarly, individuals with both an eating disorder and PTSD diagnosis present with greater general eating pathology, greater depressive symptoms, greater anxiety symptoms, and poorer quality of life compared with those diagnosed with an eating disorder alone (Brewerton et al., 2020), and even compared with individuals with a history of traumatic events but do not meet criteria for PTSD (Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, & Smith, 2021). Therefore, individuals with a history of traumatic events and eating pathology are arguably in great need of eating disorder treatment due to their increased psychopathology.

However, a previous review concluded that the effect of traumatic event exposure and/or PTSD on eating disorder treatment outcomes is unknown (Trottier & MacDonald, 2017). Researchers have argued that treatment of trauma-related symptoms and PTSD must occur for eating disorder remission to be possible (Brewerton, 2007). Typically, this argument is based on findings that suggest a functional relationship between posttraumatic symptoms and eating symptoms. Specifically, posttraumatic stress symptoms, such as negative alterations in cognition, may cause or exacerbate existing negative beliefs about the self and body, contributing to overvaluation of eating, weight, and shape and their control, perfectionism, and low self-esteem (K. S. Mitchell, Scioli, et al., 2021; Trottier et al., 2016). Therefore, without dismantling these posttraumatic beliefs, three important maintaining mechanisms for eating disorders would persist. Furthermore, emotion dysregulation, or difficulty regulating emotional responses, is a correlate of PTSD, and eating disorder behaviors can serve as maladaptive emotion regulation tools (K. S. Mitchell, Scioli, et al., 2021; Trottier et al., 2016). Indeed, multiple cross-sectional analyses have found that emotion regulation difficulties mediate the association between traumatic events and/or PTSD and eating pathology (Mills et al., 2015; K. S. Mitchell & Wolf, 2016; Moulton et al., 2015; Racine & Wildes, 2015), indicating that eating disorder symptoms may be used to cope with negative affect. For example, individuals with PTSD and eating pathology in qualitative studies have endorsed eating to manage the irritability associated with their assault (Breland et al., 2018). Trottier et al. (2016) hypothesize that eating disorder behaviors such as binge eating, restriction, and purging may function as avoidance for hyperarousal, intrusion, and negative affect symptoms associated with PTSD. For example, some patients report avoiding foods associated with their assault (Mott et al., 2012). Quantitatively, network analyses have found associations between binge eating and irritability (Vanzhula et al., 2019), cognitive restraint and reexperiencing symptoms (Liebman et al., 2021), and depressed mood and overeating (Rodgers et al., 2019), indicating a potential functional link between uncomfortable emotional experiences associated with PTSD symptoms and eating disorder symptoms as self-medication (Brewerton, 2011). Therefore, the existing theory would suggest that eating disorder treatment may be less efficacious if posttraumatic symptoms are not addressed simultaneously.

However, the evidence that eating disorder symptom reduction during eating disorder treatment is impaired by a history of experiencing traumatic events or PTSD is mixed, with some studies finding that exposure to traumatic events and/or a diagnosis of PTSD in individuals leads to reduced efficacy compared with unexposed or undiagnosed peers (e.g., Rodríguez et al., 2005) and some finding no differences between these groups (e.g., K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al., 2021). Furthermore, evidence that comorbid PTSD or exposure to traumatic events is associated with greater dropout from eating disorder treatment is also mixed (e.g., Castellini et al., 2018; Trottier, 2020). Therefore, the current review seeks to examine whether the evidence suggests that individuals diagnosed with PTSD or exposed to traumatic events are more like a) to drop out of eating disorder treatment than their peers and b) experience impaired symptom reduction as compared with their peers in eating disorder treatment.

The objective of the current study was to systematically review the literature examining how exposure to traumatic events or PTSD is associated with outcomes for eating disorder treatment. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s definition, trauma is defined by the three “E’s”: events, experiences, and effects (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Events are occurrences that include an extreme threat of physical or psychological harm, experiences are the individual’s interpretation or understanding of the event, and effects are the physical and mental sequelae. Therefore, the current study will examine both exposures to traumatic events and PTSD separately in association with eating disorder outcomes. Further, given that traumatic event exposure does not necessarily imply that the individual experienced any negative effects, we may expect that the effects of PTSD – as an expression of that negative sequelae – would be stronger than that of traumatic exposure alone. We sought to determine whether there was evidence of an association between traumatic event exposure or PTSD and poorer eating disorder symptom outcomes from treatment, which would suggest that researchers should consider methods of improving outcomes from eating disorder treatment.

2. METHOD

See supplemental materials for the systematic review protocol. This review was not preregistered as it was originally conducted in fulfillment of doctoral training requirements and therefore ineligible for registration on PROSPERO.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies included only clinical cases of eating disorders, meaning that individuals must have been diagnosed with an eating disorder either by DSM or ICD (World Health Organization, 2019) standards. Individuals must have been engaging in psychological therapy designed to treat eating disorders; there were no restrictions placed on the modality of treatment administered. Traumatic event exposure, defined as including both events that meet the DSM Criterion A for PTSD and other events typically encompassed under the umbrella of adverse childhood experiences (e.g., emotional abuse, neglect), must have been assessed or PTSD must have been diagnosed. For studies that examined traumatic events, exposure must have been examined on a binary scale such that a group that was exposed to a traumatic event was compared to a group that had no such exposure. For studies that examined PTSD, a group that was diagnosed with PTSD (including presumptive positive diagnoses through questionnaires) must have been compared with a group that was not diagnosed with PTSD. Finally, studies must have examined whether experiencing a traumatic event or PTSD predicted or moderated eating disorder psychological treatment outcomes, including symptom change or treatment termination/dropout. All quantitative and mixed-method studies were included. Case reports, review articles, and studies published in a non-English language were excluded. If data from the same study were presented in another publication, only data from the most comprehensive report were included. No inclusion or exclusion criteria based on the publication date or the duration of the study period were imposed.

2.2. Data sources and search strategy

The protocol for the systematic review was based on the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Articles were identified by searching the online databases of MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Web of Science, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and ProQuest between July and August 2022. A final search was conducted on September 2nd, 2022. The following search terms were used in the databases: (“eating disorders” or “anorexia” or “bulimia” or “disordered eating” or “binge eating disorder” or “binge eating” or “eating pathology” or “eating disorder symptoms”) AND (“trauma” or “PTSD” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “traumatic events” or “trauma history” or “posttraumatic stress disorder” or “adverse childhood experiences” or “physical abuse” or “emotional abuse” or “sexual abuse” or “emotional neglect” or “physical neglect”) AND (“predictor” or “moderator” or “treatment outcomes” or “outcome of treatment” or “response to treatment” or “treatment termination” or “treatment response”). Results were uploaded into Rayyan, a systematic review software that was used to facilitate screening.

2.3. Study selection

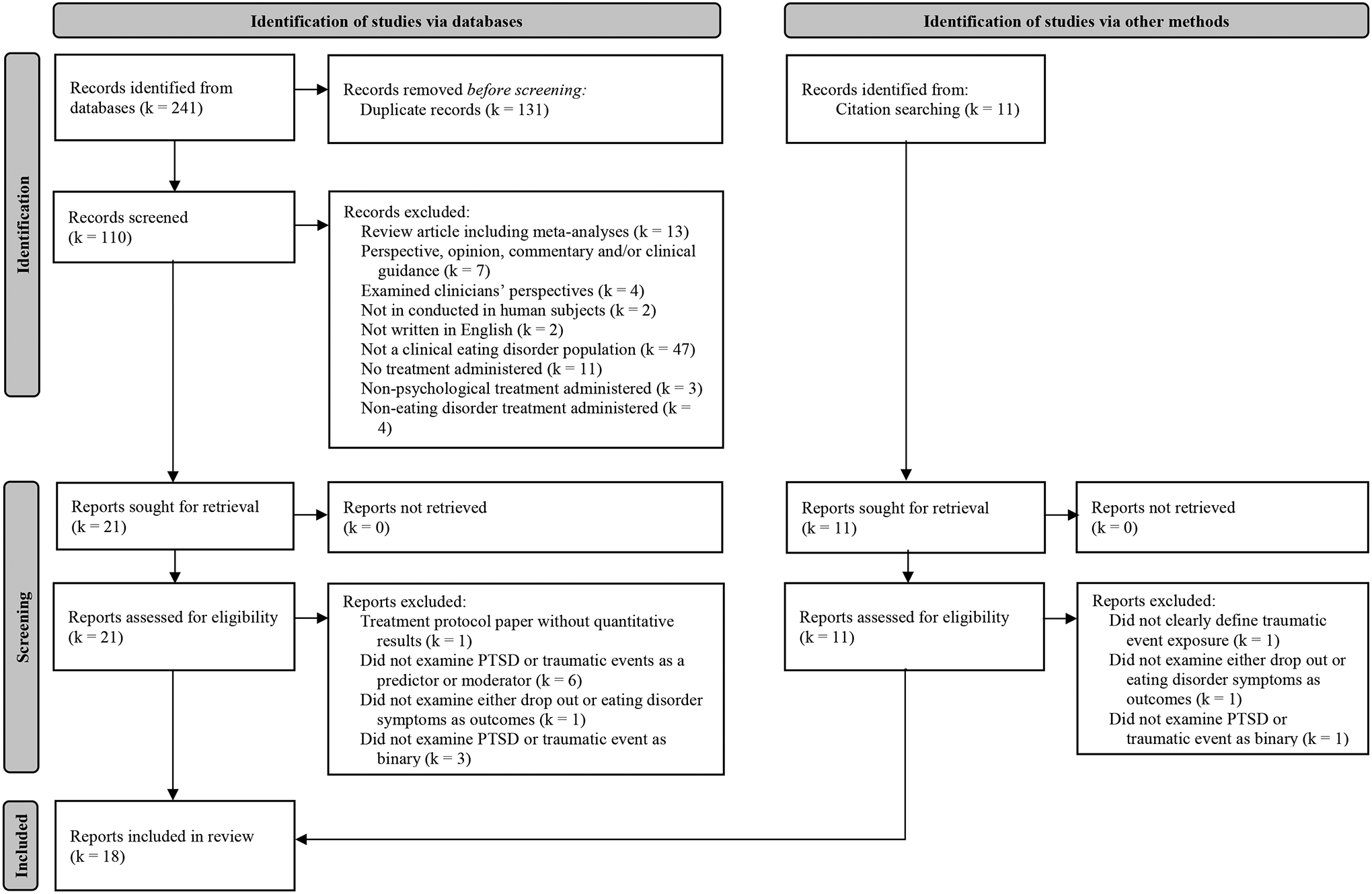

The study selection process consisted of a three-stage process. In stage 1, studies were selected based on the title and abstract. Within the title and/or abstract, it was required that: (1) participants were diagnosed with an eating disorder and undergoing treatment for this disorder, and (2) participants were assessed for traumatic events and/or PTSD. Unclear articles were moved to stage 2 of screening. In stage 2, full texts were assessed to determine if they fit the full eligibility criteria (including that traumatic events and/or PTSD were examined as a predictor or moderator of treatment outcome). In stage 3, references from included papers and manuscripts that cited the included papers were examined to identify additional eligible papers. Each author conducted study screening independently. The agreement rate was 96% at the title and abstract screening and 97% at full text. After screening, the authors discussed any papers where there was uncertainty about inclusion until a consensus was reached. A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in Figure 1 with further details about included and excluded studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of screening and selection process

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

The following items were extracted from each study: sample size, age range, sex/gender composition including assessment method, racial/ethnic composition, socioeconomic status composition, level of care (i.e., outpatient, intensive outpatient, partial hospitalization, residential, inpatient), type of eating disorder treatment, criteria used for eating disorder diagnosis, eating disorder diagnoses included, traumatic event and/or PTSD assessment method, treatment outcome(s), and results regarding the association between traumatic events and/or PTSD and treatment outcomes.

2.5. Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies (Thomas et al., 2004). Procedures for assessing quality followed published documents on use (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2010). Studies were examined on six components: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawals/dropouts. A rating of “strong,” “moderate,” or “weak” was assigned for each component (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2010). Studies were then given a global rating such that studies with no “weak” ratings were categorized as “strong,” studies with one “weak” rating were categorized as “moderate,” and studies with two or more “weak” ratings were categorized as “weak.” Agreement was almost perfect between the two authors’ ratings, κ = 0.96 (95% CI: 0.92; 1.00), p < .001. Disagreements between raters were resolved through discussion and a final rating was achieved through consensus. While assessed, no inclusion/exclusion criteria were imposed based on the study quality rating. Therefore, studies were included regardless of the quality rating.

3. RESULTS

Search results are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). A total of 241 records were identified through database searching. After removing duplicates, 110 titles and abstracts were reviewed. Of these, 21 reports were retrieved, and full texts were reviewed for eligibility. An additional 11 articles were identified through hand-searching of references. Eighteen articles were included in the final review.

Characteristics of the included papers are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Study sample sizes ranged widely from 26 (Strangio et al., 2017) to 2,809 (K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al., 2021), but the average was 317 participants (SD = 663) for a total sample size of 5,713 participants across studies. All studies included more women and girls (N = 5,606 across studies) than other genders and almost half of the studies (k = 8) were conducted in samples that were exclusively women and/or girls. Only one study described their assessment of sex as “sex assigned at birth” (Hicks, 2016); otherwise, studies did not describe how sex and gender were assessed. Most studies only reported the percentage of women/girls included in the study but did not define the other group; thus, due to this limitation in reporting, the total sample across studies of other genders/sexes is unknown. Studies were most frequently conducted at the inpatient (k = 6) level of care, but studies were also conducted at the outpatient (k = 4), residential (k = 3), and partial hospitalization (k = 2) levels of care. Three studies used a stepped-care model (Carter et al., 2012; Cook et al., 2022; Ridley, 2009). All studies but one were conducted in adolescents or early adults (k = 17). The one study not conducted in adolescents or early adults examined treatment outcomes for BED alone and the average age was late 30s (Hazzard et al., 2021). Studies varied widely in the eating disorder diagnoses included. Four studies included only anorexia nervosa (AN) diagnoses (Calugi et al., 2018; Carter et al., 2006; Hicks, 2016), one study included only bulimia nervosa (BN) diagnoses (Fallon et al., 1994), one study included only binge eating disorder (BED) diagnoses (Hazzard et al., 2021), and one study only included “binge spectrum diagnoses” (see Table 1 for further details; K. P. Anderson et al., 1997). The most common theoretical orientation of treatment administered was cognitive behavioral therapy (k = 11). Other forms of therapy included psychodynamic therapy (Masson et al., 2007; Rodríguez et al., 2005; Strangio et al., 2017), dialectical behavior therapy (Carter et al., 2012; Hicks, 2016), integrative cognitive-affective therapy (Hazzard et al., 2021), family-based therapy (Hicks, 2016), and interpersonal psychotherapy (Carter et al., 2012). Six studies did not report specific theoretical orientation or procedures used in the eating disorder treatment for some or all participants (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Carter et al., 2006; Cook et al., 2022; Fallon et al., 1994; Luadzers, 1998; Ridley, 2009). Finally, only one study was a randomized controlled trial; this study examined whether PTSD moderated the outcomes of a trial comparing Integrative Cognitive‐Affective Therapy (ICAT) to guided self‐help cognitive behavioral therapy (Hazzard et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining traumatic events in relation to eating disorder outcomes

| Author and Year | N | Participant Characteristics | Level of Care | Type of ED Treatment | ED Criteria | ED Diagnoses Included | Traumatic Event Assessment | Psychological Outcome | Quality Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (1997) | 74 | Mage = 27 (SD = 9.3); 100% women; 89% Caucasian; 98% had at least a high school education | Inpatient | Unspecifieda | DSM-III-R for AN and BN; DSM-IV provisional diagnosis for BED | AN (only bulimic subtype, those historically diagnosed with BN, or those diagnosed concurrently with BN), BN, and BED | Sexual abuse endorsement prior to age 17 | Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2); bulimic behaviorsb | Moderate | ns reduction in symptoms; patients with abuse were more likely to be re-hospitalized during a 3-month follow-up period |

| Calugi et al. (2018) | 81 | Mage = 23.6 (SD = 6.2); 96.3% women/girls; race/ethnicity and SES information NR | Inpatient | Enhanced CBT | DSM-5 | AN | Unwanted sexual experience involving physical contact prior to the age of 18 and prior to the onset of an eating disorder | Eating Disorder Examination (EDE); treatment dropout | Weak | no difference in treatment dropout or trajectory at post-treatment, as well as 6- and 12-month, follow up assessments |

| Carter et al. (2006) | 77 | Mage = 25.5 (SD = 7.8); 100% female; 93% Caucasian, 3% Asian, 4% either African Canadian or East Indian; 49% students, 14% unemployed, 37% employed | Inpatient | Unspecifiedc | DSM-IV | AN-BP, AN-R | Unwanted sexual experience involving physical contact prior to the age of 18 and prior to the onset of an eating disorder | Premature treatment termination | Weak | AN-BP patients with traumatic events terminated treatment earlier and at a faster rate than AN-R patients with or without traumatic events and AN-BP patients without traumatic events |

| Carter et al. (2012) | 100 | Mage = 25.4 (SD = 7.7); 95% female, 5% male; 94% Caucasian, 4% Asian, 2% African Canadian or East Indian; 48% students, 41% employed, 11% unemployed | Stepped care (inpatient and partial hospitalization) | CBT, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) skills training, and interpersonal therapy (IPT) | DSM-IV | AN | Childhood physical or sexual abuse | Relapsed | Weak | Childhood physical abuse was associated with a greater likelihood of relapse during the 1-year follow-up period. |

| Castellini et al. (2018) | 133 | No abuse Mage = 27.36 (SD = 7.55); History of abuse Mage = 25.30 (SD = 7.46); 94.7% female; 100% Caucasian; SES information NR | Outpatient | CBT | DSM-IV | AN, BN | Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire (CECAQ) | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q); treatment dropout; hospitalization | Moderate | Patients with a history of childhood abuse reported higher dropout during treatment; Childhood abuse group had greater hospitalization and lower recovery at follow-up; ns in change in EDE-Q score over time |

| Fallon et al. (1994) | 46 | Recovered Mage = 8 (SD = 6); Not recovered Mage = 29 (SD = 6); 100% women; race/ethnicity and SES information NR | Inpatient | Unspecifiede | DSM-III-R | BN | Childhood sexual abuse (required physical sexual contact with or genital exposure by an adult at least 5 years older) and/or childhood physical abuse (history of physical beatings that left marks or bruises) that occurred prior to the age of 17 and the patient considered it to be “abusive” | Recovery, where two groups were designated: 1) no reported bingeing or purging for at least 8 weeks, as compared to 2) met full criteria for DSM-III-R BN | Weak | Patients with a history of childhood physical abuse were more likely to still meet criteria for BN at follow-up; ns difference for childhood sexual abuse |

| Hicks (2016) | 61 | Mage = 15.2 (SD = 1.73); 91.8% female, 8.2% male (assessed as sex assigned at birth); 85.2% White; SES information NR | Outpatient | Program included Family-Based Therapy (FBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and CBT | DSM IV-TR | AN | Childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, exposure to domestic violence, parents’ divorce, significant bullying, motor vehicle accident, neighborhood violence, war terrorism, medical procedures, national disaster, and significant death/loss | Weight restoration | Weak | ns |

| Luadzers (1998) | 82 | Mage = 28.1 (SD = NR); 100% women; 98% Caucasian, 2% African American; SES information NR | Residential | NR | DSM-III or DSM-III-R | AN, BN, EDNOS | Sexual Events Questionnaire 2 (SEQ2) | Treatment outcomef | Weak | ns |

| Ridley (2009) | 214 | Mage = 22.03 (SD = 7.53); 100% women/girls; 96.5% Caucasian, 0.6% Black, 0.6% Asian, 0.3% Hispanic; 44.1% some college, 21.4% some high school; 18.8% high school degree; 10.4% college degree; 3.5% some junior high | Stepped care (inpatient, residential, outpatient) | Unspecifiedg | NR | AN, BN, EDNOS | Childhood sexual abuse as endorsed on the Life Events Survey (LES) | Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) | Moderate | Childhood sexual abuse was associated with EAT scores at follow-up after treatment. |

| Rodríguez et al. (2005) | 160 | Mage = 21.4 (SD = 7.21); 100% women; race/ethnicity information NR; 8.75% socioeconomic group Level 3, 23.12% Level 4, 28.75% Level 5, 39.38% Level 6h | Outpatient | CBT, psychodynamic, group therapy, family therapy | DSM-IV | AN, BN, BED | Prior to eating disorder onset, sexual abuse, physical abuse, self or family exposure to threats, kidnapping, extortion, homicide, or forced displacements because of violent acts | Treatment dropout, relapsei, weight loss or return to low weight baseline, restrictive intake in AN | Moderate | The probability of not having obtained a satisfactory response to treatment 4 months after the beginning of treatment increases if the patient had been exposed to a violent act or has been the victim of repeated sexual abuse. The dropout rate and rate of relapses of eating disorder symptoms were greater among patients who were exposed to trauma. |

| Strangio et al. (2017) | 26 | Median age = 16 (Interquartile Range = 3); 61.5% female, 38.5% male; race/ethnicity and SES information NR | Partial Hospital | Psychodynamic | DSM-5 | AN, BN, BED, ARFID | Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-short form (CTQ-sf) | Eating Disorder Inventory-3 (EDI-3) | Weak | ns |

| Vrabel et al. (2010) | 74 | Mage = 29.0 (SD = 7.3); 98.8% women; 100% Caucasian; SES information NR | Inpatient | CBT | DSM-IV | AN, BN, EDNOS | Childhood sexual assault, defined as any involuntary, repetitive sexual experiences with an adult (not necessarily a parent or relative) that occurred before the age of 16 years | Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) | Weak | Childhood sexual assault significantly predicted changes in global EDE score; this effect was moderated by the presence of comorbid avoidant personality disorder. |

Note. Participant characteristics are included in this table as reported in the source paper. Assessment of sex and gender was not described unless otherwise specified. AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype; ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; BED = binge eating disorder; BN = bulimia nervosa; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; ED = eating disorder; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; ICD = International Classification of Diseases; NR = not reported; ns = difference not supported; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder.

Treatment was described as including “participation in group, individual, and family therapies; nutritional rehabilitation; and milieu therapy” (Anderson et al., 1997).

“Bulimic behaviors” was defined as “eating-related behaviors (i.e. number of meal refusals, number of meals in which ritualistic eating behaviors were observed) and activity-related behaviors (number of days overt or surreptitious exercising was observed)” (Anderson et al., 1997).

Treatment was described as “an intensive group therapy program that is primarily directed at the normalization of eating and the restoration of body weight to a body mass index” (Carter et al., 2006).

Relapse was defined as “BMI [body mass index] less than or equal to 17.5 for 3 consecutive months or at least one episode of BP [binge-purge] behavior per week for 3 consecutive months during the 1-year follow-up period” (Carter et al., 2012).

Treatment was described as “behavioral methods to help…control food intake, as well as individual psychotherapy. pharmacotherapy if indicated, group therapy, and, with many patients, family therapy” (Fallon et al., 1994).

Treatment outcomes were categorized into good, intermediate, and poor outcomes based on different criteria for AN and BN. Patients diagnosed with AN were categorized in the following manner: 1) Good outcome: normal body weight (100 ± 15% average body weight) with normal menstruation; 2) Intermediate outcome: normal or near normal weight (75–110% average body weight) and/or menstrual abnormalities and/or bingeing or purging one to three times per month; and 3) Poor outcome: low weight; absent or scanty menstruation; dead; bingeing and/or purging more than weekly (Luadzers, 1998). Patients diagnosed with BN were categorized in the following manner: 1) Good outcome: Bingeing once a month or less and no purging behaviors during the past 4 weeks; 2) Intermediate outcome: Bingeing and/or purging at a frequency of one to three times during the past 4 weeks; and 3) Poor outcome: Bingeing and/or purging at a frequency of 4 or more times in the past 4 weeks (Luadzers, 1998).

Treatment was described as “guided by current research and established guidelines for eating disorder management” and as involving family therapy (Ridley, 2009).

Socioeconomic groupings were described as “six levels for the purposes of assisting the less-favored socioeconomic groups, with Level 1 being the poorest group and Level 6 being the wealthiest group” (Rodríguez et al., 2005).

Relapse was defined as “a return to baseline bingeing or vomiting frequency in purging subtypes, for at least 2 consecutive weeks” (Rodríguez et al., 2005).

Table 2.

Summary of studies examining posttraumatic stress disorder in relation to eating disorder outcomes

| Author and Year | N | Participant Characteristics | Level of Care | Type of ED Treatment | ED Criteria | ED Diagnoses Included | PTSD Assessment | Psychological Outcome | Quality Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cook et al. (2022) | 272 | Mage= 29.07 (SD = 10.57); 87.3% female; race/ethnicity and SES information NR | Stepped care (residential, partial hospitalization, and intensive outpatient) | Unspecifieda | DSM-5 | AN, BN, BED, ARFID, OSFED | PCL-5 used as presumptive positive current PTSD diagnosis | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) | Weak | Less improvement in eating disorder symptoms was observed after treatment in participants with PTSD in 2020 as compared to participants in 2019 |

| Hazzard et al. (2021) | 112 | Mage= 39.7 (SD = 13.4); 82.1% cisgender women; 91.1% Caucasian; 68.8% college degree | Outpatient | Integrative Cognitive‐ Affective Therapy (ICAT) or guided self‐help CBT | DSM-5 | BED | Lifetime diagnosis | Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) | Moderate | PTSD predicted greater objective binge‐eating episode frequency at end of treatment; moderate/severe childhood abuse predicted greater objective binge‐eating episode frequency at 6‐month follow‐up only for the PTSD group; ns for global eating pathology |

| Hicks (2016) | 61 | Mage = 15.2 (SD = 1.73); 91.8% female, 8.2% male (assessed as sex assigned at birth); 85.2% White; SES information NR | Outpatient | Program included Family-Based Therapy (FBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), and CBT | DSM IV-TR | AN | Diagnosis (unknown timeframe) | Weight restoration | Weak | ns |

| Masson et al. (2007) | 186 | Mage = 26.5 (SD = 9.4); 93% women; race/ethnicity information NR; 20% high school diploma, 29% some college or university, 19% undergraduate degree | Inpatient | Based on a cognitive behavioral approach incorporating psychodynamic, and psychoeducational treatment options. | DSM-IV | AN, BN, EDNOS | Current diagnosis | Treatment dropout | Weak | ns |

| K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al. (2021) | 2,809 | Mage = 25.14 (SD = 10.99); 100% female; 80.5% White, 2.1% Black, 2.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.5% Native American, 3.5% multiracial, 2.2% other races; 6.1% Latinx; SES information NR for the sample as a whole | Residential | Unified Treatment Model (based on CBT) | DSM-5 | AN-R, AN-BP, BN, OSFED/UFED, BED, ARFID | Current diagnosis | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q), behavioral outcomes, treatment dropout | Moderate | ns |

| Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, Smith, et al. (2021) | 1055 | Mage = 24.73 (SD = 10.72); 100% women/girls; 80.9% White; SES information NR | Residential | Unified Treatment Model (based on CBT) | DSM-5 | AN-R, AN-BP, BN, BED, OSFED | Current diagnosis | Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) | Moderate | PTSD was associated with more substantial symptom reductions from admission to discharge, yet also a steeper rate of symptom recurrence from discharge to follow‐up. |

| Trottier (2020) | 151 | Mage = 28.1 (SD = 8.6); 94.7% female; 4.6% male; 0.7% transgendered; race/ethnicity and SES information NR | Partial Hospital | CBT | DSM-5 | BN, OSFED | PCL-5 used as presumptive positive current PTSD diagnosis | Non-completion of treatment | Strong | PTSD predicted a greater risk of premature termination |

Note. Participant characteristics are included in this table as reported in the source paper. Assessment of sex and gender was not described unless otherwise specified. AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype; ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; BN = bulimia nervosa; BED = binge eating disorder; CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy; DSM = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; ED = eating disorder; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; ns = difference not supported; OSFED = other specified feeding and eating disorders; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; UFED = unspecified feeding or eating disorder.

Treatment was described as “an integrated and adaptive model that includes specialized evidence-based practices in therapy, nutrition, medical, movement/exercise, and relational components of eating disorder care” (Cook et al., 2022).

Most studies were classified as weak (k = 10; see Tables 1 and 2 for global quality assessment ratings; Table 3 contains all quality assessment ratings by component). Seven studies were classified as moderate, and one study was classified as strong. A notable limitation of the included studies was measurement methods that did not have available or reported psychometric properties. Of the 12 studies that examined the association between exposure to traumatic events and eating disorder treatment outcomes, less than a third of the studies (k = 4) used measures of traumatic events with published psychometric examinations. The remaining studies relied on clinical interviews with unpublished or unspecified psychometric properties. Of these studies, the definitions and specificity of traumatic events varied widely. For example, Carter et al. (2012) stated that a “history of physical or sexual abuse” (p. 519) was examined, but not what specific events were categorized as abuse. In contrast, Anderson et al. (1997) stated:

For this study, child sexual abuse was defined as…all types of contact abuse (i.e. abuse involving sexual contact, including fondling, rubbing of genitals against the victim’s body, attempted or completed vaginal intercourse, oral sex and anal sex), and noncontact abuse (i.e. sexual behaviors that do not involve physical contact between perpetrator and victim, such as exposure of the genitals and solicitations to engage in sexual activity), regardless of the relationship between victim and perpetrator, with the exception of consensual incidents with peers.

(p. 624)

Studies, therefore, varied in the extent that they provided specific guidelines on how traumatic events were defined.

Table 3.

All quality ratings by component for included studies

| Author and Year | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blindinga | Data Collection Method | Withdrawals/ Dropoutsb | Global Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (1997) | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Strong | Moderate |

| Calugi et al. (2018) | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Carter et al. (2006) | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak |

| Carter et al. (2012) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Castellini et al. (2018) | Strong | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Strong | Moderate |

| Cook et al. (2022) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Fallon et al. (1994) | Strong | Weak | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Not applicable | Weak |

| Hazzard et al. (2021) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | NA, secondary data analysis of randomized controlled trial | Strong | Weak | Moderate |

| Hicks (2016) | Strong | Moderate | Weak | NA, retrospective chart review | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Luadzers (1998) | Weak | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

| Masson et al. (2007) | Strong | Moderate | Weak | NA, retrospective chart review | Weak | Not applicable | Weak |

| K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al. (2021) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | NA, secondary data analysis of routinely collected outcome data | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Ridley (2009) | Moderate | Moderate | Weak | NA, retrospective chart review | Strong | Not applicable | Moderate |

| Rodríguez et al. (2005) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Not applicable | Moderate |

| Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, Smith, et al. (2021) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | NA, secondary data analysis of routinely collected outcome data | Moderate | Weak | Moderate |

| Strangio et al. (2017) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak | Weak |

| Trottier (2020) | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | NA, secondary data analysis of routinely collected outcome data | Strong | Not applicable | Strong |

| Vrabel et al. (2010) | Strong | Moderate | Weak | Weak | Strong | Strong | Weak |

Note. NA = not applicable.

“Not applicable” ratings were given if it was clear that the current research questions were part of a secondary data analysis or retrospective chart review.

“Not applicable” ratings were given if the study design was retrospective case-control.

Similarly, of the seven studies that examined PTSD in association with eating disorder treatment outcomes, five studies assessed PTSD using clinical interviews, and two studies examined presumptive positive PTSD diagnoses based on the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Cook et al., 2022; Trottier, 2020). Of the studies that examined clinician-rated diagnoses, only one was stated to use a validated clinical interview (i.e., Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID); Hazzard et al., 2021) while the other four studies did not specify the type of clinical interview conducted.

3.1. Traumatic Events

Characteristics of the studies that examined traumatic events in relationship with eating disorder outcomes are reported in Table 1. Most studies (k = 12) examined traumatic events and of these studies, only three studies included traumatic events across the lifespan (Hicks, 2016; Luadzers, 1998; Rodríguez et al., 2005). Therefore, while the current study includes traumatic events from across the lifespan, results should be taken with some caution given that most studies only included childhood traumatic events. Furthermore, three studies limited their assessment of traumatic events to only before the onset of the eating disorder (Calugi et al., 2018; Carter et al., 2006; Rodríguez et al., 2005).

3.1.1. Treatment Dropout

Four studies examined treatment dropout as an outcome. Of these studies, two found that traumatic events (childhood traumatic events, Castellini et al., 2018; any traumatic event history before eating disorder onset, Rodríguez et al., 2005) were associated with greater treatment dropout. One study found that dropout rates depended on both diagnosis and traumatic event exposure, such that AN-BP patients with traumatic event histories in childhood before eating disorder onset were more likely to terminate treatment prematurely compared to individuals without traumatic events or AN-R patients with traumatic event histories (Carter et al., 2006). Finally, one study did not find any difference between individuals that were exposed childhood traumatic events before the eating disorder onset and those that had not been exposed (Calugi et al., 2018). Therefore, three of four studies that examined treatment dropout as an outcome found some effect of traumatic events on dropout likelihood.

3.1.2. Reduction in Eating Disorder Symptoms

Eleven studies examined eating disorder symptoms as outcomes from treatment. Of these studies, seven examined differences at the end of treatment between individuals exposed to traumatic events compared with their unexposed peers. The majority of these studies (k = 6) demonstrated significant reductions in both groups in eating pathology at the end of treatment but no differences between the groups (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Calugi et al., 2018; Castellini et al., 2018; Hicks, 2016; Luadzers, 1998; Strangio et al., 2017), suggesting that individuals with traumatic events across the lifespan benefited equally from treatment. The one study that demonstrated a significant effect of childhood sexual abuse on the trajectory of eating pathology scores over time (including treatment termination) found a significant moderation effect, such that this main effect was qualified by a significant interaction with avoidant personality disorder (Vrabel et al., 2010). This study further did not report whether childhood sexual abuse was associated with differences in eating pathology post-treatment alone. Therefore, at least six of the seven studies examined found no differences between individuals exposed to traumatic events and unexposed peers.

Eight studies examined follow-up periods after treatment (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Calugi et al., 2018; Carter et al., 2012; Fallon et al., 1994; Luadzers, 1998; Ridley, 2009; Vrabel et al., 2010). Of these studies, two studies (Calugi et al., 2018; Luadzers, 1998) did not find differences after treatment between individuals that were exposed to sexual assault and those that were not. Four studies found differences such that patients with childhood traumatic events were more likely to be hospitalized or re-hospitalized (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Castellini et al., 2018), less likely to achieve symptom remission (Castellini et al., 2018; Fallon et al., 1994), and more likely to relapse (Carter et al., 2012). For two studies (Ridley, 2009; Vrabel et al., 2010), interpretation is difficult due to methodological differences in reporting and analysis. Ridley et al. (2009) found that individuals exposed to childhood sexual abuse demonstrated higher eating disorder symptomology at follow-up than their unabused peers; however, this study did not control for pre-treatment or termination eating pathology scores. Therefore, the observed effect may be due to baseline differences in eating pathology between groups, meaning that individuals with childhood sexual abuse histories begin with higher pathology and demonstrate equivalent change over time compared to their unabused peers, but maintain the mean difference between groups. As noted previously, Vrabel et al. (2010) examined childhood sexual abuse, but this effect was qualified by a significant interaction with avoidance personality disorder and the main effects at follow-up timepoints of childhood sexual abuse were not reported. Therefore, four of six studies without methodological differences hampering interpretation found that childhood traumatic events were associated with poorer outcomes during the follow-up period (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Carter et al., 2012; Castellini et al., 2018; Fallon et al., 1994).

One study examined differences in eating disorder symptoms at the end of the first four months of treatment, although treatment extended beyond four months. Rodríguez et al. (2005) was therefore difficult to compare to studies that examined a full course of treatment or follow-up periods after treatment. This study found that any traumatic event before eating disorder onset was significantly associated with reduced early symptom remission and an increased relapse rate (Rodríguez et al., 2005).

3.2. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

A minority of studies (k = 7) examined PTSD as a moderator or predictor; the characteristics of these studies are reported in Table 2. Most studies (k = 5) examined current diagnosis of PTSD at admission. One study examined lifetime diagnoses (Hazzard et al., 2021), and one study did not specify when the diagnosis was made (Hicks, 2016).

3.2.1. Treatment Dropout

Three studies examined treatment dropout by PTSD diagnosis. K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al. (2021), and Masson et al. (2007) found that PTSD was not associated with dropping out of treatment; however, Trottier (2020) found that PTSD was associated with premature termination. Of note, K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al. (2021) defined treatment dropout as terminating treatment against either medical or team advice. Similarly, Masson et al. (2007) described that dropout included discharge without or against recommendations from their team, and included administrative discharges when patients were asked to leave the program due to non-compliance. Trottier (2020), in contrast, defined premature treatment termination as not completing at least 6 weeks of partial hospital treatment, without considering the reasons for termination.

3.2.2. Reduction in Eating Disorder Symptoms

Five studies examined the reduction in eating disorder symptoms during treatment as a function of PTSD diagnosis and for all these studies, patients overall experienced significant decreases in eating pathology after treatment. Two studies found no association between PTSD diagnosis and eating disorder treatment outcomes at post-treatment (Hicks, 2016; K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al., 2021) or six-month follow-up (K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al., 2021). Three studies found that PTSD predicted or moderated treatment outcomes. Hazzard et al. (2021) found that PTSD predicted greater objective binge episode frequency at the end of treatment, but there was no significant main effect of PTSD at the six-month follow-up. Further, PTSD moderated the association between moderate/severe child abuse and binge frequency such that individuals who were exposed to moderate/severe child abuse and a lifetime PTSD diagnosis presented with greater binge frequency at the six-month follow-up as compared to individuals with moderate/severe child abuse that did not have a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD. Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, Smith, et al. (2021) found that PTSD was associated with more substantial eating disorder symptom reductions while in treatment, but greater symptom recurrence at six-month follow-up. Finally, Cook et al. (2022) examined differences in eating disorder treatment trajectory by PTSD diagnosis and treatment year (2019 vs. 2020) to examine the potential influence of COVID-19 on treatment. They found that individuals with a PTSD diagnosis who were treated in 2020 experienced less symptom improvement than individuals that were treated in 2019, regardless of PTSD diagnosis, and individuals who were treated in 2020 without PTSD.

4. DISCUSSION

The current review examined whether traumatic event exposure and/or PTSD predicted or moderated treatment outcomes in individuals undergoing treatment for an eating disorder. The majority of studies (with one exception) indicated that individuals with traumatic event histories were more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely compared with those without such a history. Difficulties with trust– a common posttraumatic symptom – emerging in the context of a therapeutic relationship may explain this finding. The treatment process for an eating disorder involves the patient trusting the practitioner’s recommendations for eating, weight, and compensatory behaviors (Trim et al., 2018). Thus, trauma-related tendencies to distrust may lead to premature termination of treatment. Alternatively, since weight restoration is often prioritized in eating disorder treatment if the patient is underweight, individuals with a traumatic event history may perceive that the focus on weight restoration ignores posttraumatic symptoms that they find concerning. Therefore, individuals with traumatic events in their past may benefit from additional interventions to ensure treatment engagement.

However, the evidence also suggests that individuals with traumatic event histories can equally benefit from treatment compared with those without a history of traumatic events, despite baseline differences in symptomology (Backholm et al., 2013; Scharff, Ortiz, Forrest, & Smith, 2021). This finding is attenuated by evidence suggesting that when longer follow-up periods are included after the termination of treatment, individuals with traumatic event histories are more likely to experience increases in symptomology (K. P. Anderson et al., 1997; Carter et al., 2012; Castellini et al., 2018; Fallon et al., 1994). Future research would benefit from examining patient outcomes after the end of treatment to potentially replicate this finding. Qualitatively, former patients endorse the idea that traumatic events impact their ability to fully address eating disordered behaviors (Olofsson et al., 2020). It is possible that individuals who discharge from eating disorder treatment do not subsequently receive trauma treatment, even if they have trauma-related symptoms. Given the bidirectional, functional associations between posttraumatic and eating disorder symptoms, it is then perhaps unsurprising that eating disorder symptoms will increase over time if posttraumatic symptoms remain unaddressed. Even if patients do receive subsequent trauma treatment, it is unclear whether sequential treatment will fully address the bidirectional relationships between posttraumatic and eating disorder symptoms. Thus, future research should examine what factors may explain the association between traumatic events and greater rates of relapse after treatment.

A limited number of studies have examined PTSD as a predictor or moderator of treatment; therefore, these findings are tentative, pending further research. Only three studies examined treatment dropout as a function of PTSD diagnosis, with differential findings. Of note, the three studies examined used different definitions of treatment dropout or termination, hampering comparisons across studies. Differing definitions of dropout are a common difficulty when examining dropout rates from eating disorder treatment at large (Fassino et al., 2009; Linardon, 2018), and therefore not unique to the current review. Regardless, the results assessing the effect of PTSD on premature treatment termination are equivocal. Similarly, the results from studies examining the effect of PTSD diagnosis on eating disorder symptom outcomes were also mixed. Only one of the four studies with comparable designs found an effect of PTSD on outcomes at the end of treatment. In contrast, both the studies that examined a follow-up period indicated some effect of PTSD on eating disorder outcomes. Tentatively, the pattern of results may indicate a similar pattern of results for individuals with trauma, such that individuals with PTSD achieve similar gains during treatment but experience greater symptom relapse in the follow-up period, contrary to this review’s hypothesis that individuals with PTSD would fare worse over the course of treatment. However, given the limited number of studies, this pattern cannot be supported with confidence. Further research examining the symptom trajectories after discharge is needed to further explore this provisional finding.

Further complicating the current findings, studies varied widely both in how eating pathology was assessed and the eating disorder diagnoses included. Measurement of eating pathology varied from validated measures such as the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994) or the Eating Disorder Inventory (Garner, 1991) to idiosyncratic definitions of remission or relapse. Measurement differences could therefore have influenced the observed effects across studies. Similarly, most of the studies in this review (k = 10) only included AN, BN, and/or BED, largely excluding Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and Other Specified Eating Disorder (OSFED) diagnoses. This is a limitation of the existing research when cases that do not meet full criteria for a full syndrome eating disorders are quite common (Mustelin et al., 2016; Vo et al., 2017). Further, the heterogeneity in examined diagnoses, without separating by symptom cluster, may have obscured potential effects. Previous systematic reviews have found that the association of traumatic events and eating pathology is most consistent among individuals with binge-eating/purging symptoms compared with individuals that only display restriction (Caslini et al., 2016; Molendijk et al., 2017). Potentially supporting this interpretation, Carter et al. (2006) found that, among individuals with a childhood sexual assault history, people with AN-BP diagnoses were more likely to terminate treatment prematurely compared with people with AN-R diagnoses. Therefore, future research may seek to disentangle this association by examining diagnosis as a function of outcomes, or by symptom clusters displayed. Examining eating disordered behaviors/symptoms separately may lead to further insights rather than focusing primarily on diagnoses.

The current study may have implications for clinicians in practice as well as researchers. The evidence from this systematic review suggests that individuals with a childhood traumatic event history are more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely, despite benefitting similarly from treatment when they continue compared with their peers without a history of childhood traumatic events. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of this heightened potential for dropout, and work with patients to ensure continued treatment engagement. Although this review did not examine factors that may mitigate dropout, clinicians should strongly consider the implementation of trauma-informed care. In trauma-informed care, clinicians: provide psychoeducation about traumatic events, trauma responses, and recovery from trauma-related effects; inquire about past traumatic events explicitly; and are both knowledgeable and comfortable with speaking about trauma without necessarily delivering evidence-based protocols for PTSD (Brewerton et al., 2019). Trauma-informed care has been shown to improve patient retention rates in other psychiatric concerns such as substance use disorders (Amaro et al., 2007) and anecdotal evidence suggests that eating disorder care without consideration for trauma may alienate patients (Brewerton et al., 2019). Specifically, clinicians should consider screening for traumatic events and assessing for PTSD symptoms upon intake, educating patients on how posttraumatic symptoms can present, treating patients for their PTSD or posttraumatic symptoms as they arise, and changing language throughout interactions with patients in consideration of potential trauma (Brewerton et al., 2019). Individuals with lived experience of both trauma and eating pathology report that their trauma frequently went unnoticed and unaddressed by clinicians (Brewerton et al., 2019). Furthermore, insensitive provider comments regarding traumatic events contributed to feelings of alienation from providers (Brewerton et al., 2019). Another method of practicing trauma-informed care may fall under the principle of “empowerment, voice and choice” (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Patients should be empowered with choice in treatment to the extent possible (e.g., weighing process, feeding procedures; Brewerton, 2019), while also balancing safety. For example, involuntary refeeding or hospitalization may serve as traumatic reminders for individuals (Bannatyne & Stapleton, 2018), but could also save the patient’s life (Brewerton, 2019). Systematic evaluations of trauma-informed care for eating disorders have not been conducted, but evidence from other mental health conditions supports increased retention under trauma-informed care (Amaro et al., 2007; Hales et al., 2019). Furthermore, PTSD symptoms were reduced in an eating disorder treatment program that implemented trauma-informed care (Rienecke et al., 2021). Therefore, trauma-informed care should be strongly considered by clinicians for addressing the higher dropout rate in patients with traumatic event histories.

Another method of addressing dropout and symptom relapse may include integrated treatment protocols for trauma/PTSD (K. S. Mitchell, Scioli, et al., 2021; Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, MacDonald, et al., 2017). A previous systematic review examined integrated treatment for both PTSD and an eating disorder and concluded that further research is urgently needed (Rijkers et al., 2019). However, systemic investigations of integrated treatment compared with existing models such as sequential treatment have not been investigated. Proponents of integrated treatment argue that the benefits of integrated treatment are two-fold: First, that integrated treatment can address and dismantle the bidirectional, functional relationship between the two disorders better than single diagnosis protocols alone, and second, that addressing posttraumatic symptoms simultaneously would improve treatment retention (Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, & Olmsted, 2017). Clinicians have also endorsed both these beliefs (Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, MacDonald, et al., 2017). Integrated treatment protocols are currently in their infancy (Brewerton et al., 2022; Trottier, Monson, Wonderlich, & Olmsted, 2017; Trottier & Monson, 2021), but hold promise for addressing this complex comorbidity. A recent randomized controlled trial compared integrated CBT to CBT for an eating disorder only after intensive eating disorder treatment, and integrated CBT led to greater PTSD symptom reductions at post-treatment that were maintained at three- and six-month follow-up (Trottier et al., 2022). Given that participants were enrolled following intensive eating disorder treatment, the developers did not expect further eating disorder symptom decreases in either group; as predicted, eating disorder symptom outcomes were equivalent across groups (Trottier et al., 2022). Participants in the study preferred engaging with integrated treatment over separate treatments (Trottier et al., 2022). Future research should continue to examine integrated treatments for their potential to mitigate dropout and improve treatment outcomes as compared to single diagnosis, sequential, or parallel treatment.

There are some limitations to note of the current review. First, this review included only English language publications, perhaps leading to a “Western”-centric bias in findings. Second, the racial, gender, and sex composition in the included studies tended to be largely White young women and adolescent girls. Thus, results apply primarily to this population, and other traumatic events specific to demographic factors (e.g., racial discrimination) are unlikely to have been assessed. Additionally, the current review limited the definition of traumatic exposure to events meeting Criterion A for PTSD in the DSM and adverse childhood experiences (e.g., emotional abuse or neglect). The review was further limited by studies that compared a group with traumatic event exposure to an unexposed group. The debate about defining trauma is currently ongoing in the field (Krupnik, 2019); therefore, while this review imposed a specific definition, other researchers may define trauma differently. However, given SAMHSA’s differentiation of the three “E’s” of trauma, the differentiation of traumatic events and PTSD (as a traumatic sequelae) as separate should be considered a strength of this review. An additional limitation is that the current review primarily represents papers that examine childhood trauma, although individuals with any traumatic event history across the lifespan were included. Future research therefore should seek to examine whether the timing of traumatic event exposure matters when considering eating disorder treatment outcomes (i.e., compare childhood exposure to traumatic events to adult exposure). Trauma was also universally assessed using retrospective reports, which is subject to reporting bias toward more severe and recent abuse (Goodman et al., 2003; Williams, 1994). Thus, this review may have been biased toward assessing more severe and relatively recent child abuse. Additionally, the quality of the papers in this review was skewed toward weak quality. Future researchers are encouraged to consult guidelines for reporting observational studies (e.g., STROBE; von Elm et al., 2008; Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; Wells et al., 2000) before designing and reporting studies to ensure high quality. Another consideration is that the current review only examined treatment outcomes in terms of eating disorder symptoms. Given baseline differences between groups with and without traumatic events and/or PTSD for depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and quality of life, future reviews should consider examining these outcomes from eating disorder treatment as a function of traumatic event exposure and/or PTSD, especially as patients may turn to other symptom profiles (e.g., alcohol use) as a method of avoidance. Finally, cognitive behavioral therapy was most typically used as a treatment modality for eating disorders, although this was not the only form of treatment administered. Therefore, this review may be biased toward outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy and may not generalize to other forms of treatment. Furthermore, the extent to which some treatments in these studies may have also addressed comorbid PTSD symptoms is unclear (e.g., K. S. Mitchell, Singh, et al., 2021).

Studies in the current review were required to examine PTSD or traumatic events on a binary measurement scale, such that individuals were divided into either a PTSD diagnosis or trauma-exposed group that was compared with an undiagnosed or unexposed group. The number of studies that were excluded due to this criterion (k = 4) was small and varied in assessment method. However, by imposing dichotomous measurement requirements, the current results are limited to only the association between binary indicators of traumatic events and PTSD with eating disorder outcomes. In addition, the current review found no studies that examined the association between “complex PTSD” (C-PTSD) – a condition characterized by repeated, ongoing exposure to interpersonally traumatic events beginning in childhood and symptoms such as identity and personality disturbances (Cloitre et al., 2009; Herman, 1992) – and eating disorder treatment outcomes. There is a dearth of research on the comorbidity between C-PTSD and eating disorders generally but given the multifaceted symptom profile of individuals with this comorbidity (Rorty & Yager, 1996), individuals with comorbid C-PTSD may be particularly pertinent to assess within the context of eating disorder treatment. Future studies should consider examining both PTSD and trauma by other definitions of trauma and PTSD such as self-perceived impact of trauma (e.g., Serra et al., 2020), cumulative traumatic events (e.g., Mahon et al., 2001), past compared to current diagnosis of PTSD, and C-PTSD.

The main conclusion of this review is that traumatic events appear to be associated with greater eating disorder treatment dropout. Furthemore, most studies that examined effects at the end of treatment found no difference between traumatic event exposure and non-exposed groups. Finally, traumatic events may be associated with greater eating disorder symptom resurgence after treatment ends. Future researchers are encouraged to further examine traumatic events and PTSD as predictors or moderators of treatment in the interest of greater confidence in the current findings. Specifically, studies should examine a longer follow-up period after treatment to examine the potential long-term differences in efficacy among individuals with traumatic event exposure and non-exposed peers. In addition, the number of studies examining PTSD as a factor in eating disorder treatment was small, indicating that more research should be conducted in this domain.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement.

Eating disorders (EDs), trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) often co-occur. Individuals with traumatic event exposure and/or PTSD demonstrate greater ED symptoms; it is unclear whether these individuals benefit similarly in ED treatment to their peers. The current study found that individuals with traumatic event exposure are more likely to drop out of treatment but benefit from treatment with similar symptom remission. Traumatic history was associated with greater relapse post-treatment.

Funding Sources:

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. 1842470. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number 5T34GM008303. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CRediT Statement:

Alexandra D. Convertino: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing, Visualization.

Rebecca R. Mendoza: Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Review and Editing.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The author has no conflict to declare.

Availability of Data:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ágh T, Kovács G, Supina D, Pawaskar M, Herman BK, Vokó Z, & Sheehan DV (2016). A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders, 21(3), 353–364. 10.1007/s40519-016-0264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, Chernoff M, Brown V, Arévalo S, & Gatz M (2007). Does integrated trauma-informed substance abuse treatment increase treatment retention? Journal of Community Psychology, 35(7), 845–862. 10.1002/jcop.20185 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KP, LaPorte DJ, Brandt H, & Crawford S (1997). Sexual abuse and bulimia: Response to inpatient treatment and preliminary outcome. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 31(6), 621–633. 10.1016/S0022-3956(97)00026-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, & Nielsen S (2011). Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders: A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood ME, & Friedman A (2020). A systematic review of enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT‐E) for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(3), 311–330. 10.1002/eat.23206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backholm K, Isomaa R, & Birgegård A (2013). The prevalence and impact of trauma history in eating disorder patients. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 22482. 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.22482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannatyne A, & Stapleton P (2018). Eating Disorder Patient Experiences of Volitional Stigma Within the Healthcare System and Views on Biogenetic Framing: A Qualitative Perspective. Australian Psychologist, 53(4), 325–338. 10.1111/ap.12171 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breland JY, Donalson R, Dinh JV, & Maguen S (2018). Trauma exposure and disordered eating: A qualitative study. Women & Health, 58(2), 160–174. 10.1080/03630242.2017.1282398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2007). Eating Disorders, Trauma, and Comorbidity: Focus on PTSD. Eating Disorders, 15(4), 285–304. 10.1080/10640260701454311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2011). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Disordered Eating: Food Addiction as Self-Medication. Journal of Women’s Health, 20(8), 1133–1134. 10.1089/jwh.2011.3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD (2019). An overview of trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(4), 445–462. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1532940 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD, Alexander J, & Schaefer J (2019). Trauma-informed care and practice for eating disorders: Personal and professional perspectives of lived experiences. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 24(2), 329–338. 10.1007/s40519-018-0628-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD, Perlman MM, Gavidia I, Suro G, Genet J, & Bunnell DW (2020). The association of traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder with greater eating disorder and comorbid symptom severity in residential eating disorder treatment centers. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(12), 2061–2066. 10.1002/eat.23401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewerton TD, Wang JB, Lafrance A, Pamplin C, Mithoefer M, Yazar-Klosinki B, Emerson A, & Doblin R (2022). MDMA-assisted therapy significantly reduces eating disorder symptoms in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of adults with severe PTSD. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 149, 128–135. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calugi S, Franchini C, Pivari S, Conti M, El Ghoch M, & Dalle Grave R (2018). Anorexia nervosa and childhood sexual abuse: Treatment outcomes of intensive enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychiatry Research, 262, 477–481. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Bewell C, Blackmore E, & Woodside DB (2006). The impact of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(3), 257–269. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JC, Mercer-Lynn KB, Norwood SJ, Bewell-Weiss CV, Crosby RD, Woodside DB, & Olmsted MP (2012). A prospective study of predictors of relapse in anorexia nervosa: Implications for relapse prevention. Psychiatry Research, 200(2), 518–523. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caslini M, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Dakanalis A, Clerici M, & Carrà G (2016). Disentangling the Association Between Child Abuse and Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(1), 79–90. 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini G, Lelli L, Cassioli E, Ciampi E, Zamponi F, Campone B, Monteleone AM, & Ricca V (2018). Different outcomes, psychopathological features, and comorbidities in patients with eating disorders reporting childhood abuse: A 3-year follow-up study. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(3), 217–229. 10.1002/erv.2586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN, Elamin MB, Seime RJ, Shinozaki G, Prokop LJ, & Zirakzadeh A (2010). Sexual Abuse and Lifetime Diagnosis of Psychiatric Disorders: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 85(7), 618–629. 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, & Petkova E (2009). A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity: Childhood and Adult Cumulative Trauma as Predictors of Symptom Complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(5), 399–408. 10.1002/jts.20444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, Mascolo M, Bass G, Duffy ME, Zehring B, & Beasley T (2022). Has COVID-19 Complicated Eating Disorder Treatment? An Examination of Comorbidities and Treatment Response Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 24(1). 10.4088/PCC.21m03087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project. (2010). Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies Dictionary. McMaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon BA, Sadik C, Saoud JB, & Garfinkel RS (1994). Childhood abuse, family environment, and outcome in bulimia nervosa. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 55(10), 424–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba E, & Abbate-Daga G (2009). Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: A comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry, 9(1), 67. 10.1186/1471-244X-9-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell EL, Russin SE, & Flint DD (2022). Prevalence Estimates of Comorbid Eating Disorders and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Quantitative Synthesis. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 31(2), 264–282. 10.1080/10926771.2020.1832168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM (1991). Eating Disorder Inventory-2 professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman GS, Ghetti S, Quas JA, Edelstein RS, Alexander KW, Redlich AD, Cordon IM, & Jones DPH (2003). A Prospective Study of Memory for Child Sexual Abuse: New Findings Relevant to the Repressed-Memory Controversy. Psychological Science, 14(2), 113–118. 10.1111/1467-9280.01428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales TW, Green SA, Bissonette S, Warden A, Diebold J, Koury SP, & Nochajski TH (2019). Trauma-Informed Care Outcome Study. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(5), 529–539. 10.1177/1049731518766618 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hazzard VM, Crosby RD, Crow SJ, Engel SG, Schaefer LM, Brewerton TD, Castellini G, Trottier K, Peterson CB, & Wonderlich SA (2021). Treatment outcomes of psychotherapy for binge‐eating disorder in a randomized controlled trial: Examining the roles of childhood abuse and post‐traumatic stress disorder. European Eating Disorders Review. 10.1002/erv.2823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. 10.1002/jts.2490050305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks AA (2016). Understanding correlates and comorbidities in the treatment and recovery of adolescent eating disorders [The Ohio State University]. In Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering (Vol. 78, Issue 7). https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu1471864039 [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M, McTavish JR, Couturier J, Boven A, Gill S, Dimitropoulos G, & MacMillan HL (2017). Consequences of child emotional abuse, emotional neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence for eating disorders: A systematic critical review. BMC Psychology, 5. APA PsycInfo. 10.1186/s40359-017-0202-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaersdam Telléus G, Lauritsen MB, & Rodrigo-Domingo M (2021). Prevalence of Various Traumatic Events Including Sexual Trauma in a Clinical Sample of Patients With an Eating Disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 687452. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.687452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klump KL, Bulik CM, Kaye WH, Treasure J, & Tyson E (2009). Academy for Eating Disorders position paper: Eating disorders are serious mental illnesses. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(2), 97–103. 10.1002/eat.20589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnik V (2019). Trauma or adversity? Traumatology, 25(4), 256–261. 10.1037/trm0000169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman RE, Becker KR, Smith KE, Cao L, Keshishian AC, Crosby RD, Eddy KT, & Thomas JJ (2021). Network Analysis of Posttraumatic Stress and Eating Disorder Symptoms in a Community Sample of Adults Exposed to Childhood Abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(3), 665–674. 10.1002/jts.22644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J (2018). Meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the core eating disorder maintaining mechanisms: Implications for mechanisms of therapeutic change. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(2), 107–125. 10.1080/16506073.2018.1427785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luadzers D (1998). Sexual Abuse History and Treatment Outcome of Eating Disorders. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 23(4), 312–317. 10.1080/01614576.1998.11074268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madowitz J, Matheson BE, & Liang J (2015). The relationship between eating disorders and sexual trauma. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 20(3), 281–293. 10.1007/s40519-015-0195-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon J, Winston AP, Palmer RL, & Harvey PK (2001). Do broken relationships in childhood relate to bulimic women breaking off psychotherapy in adulthood? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29(2), 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson PC, Perlman CM, Ross SA, & Gates AL (2007). Premature termination of treatment in an inpatient eating disorder programme. European Eating Disorders Review, 15(4), 275–282. 10.1002/erv.762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills P, Newman EF, Cossar J, & Murray G (2015). Emotional maltreatment and disordered eating in adolescents: Testing the mediating role of emotion regulation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 39, 156–166. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, & Crow S (2006). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 438–443. 10.1097/01.yco.0000228768.79097.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Schlesinger MR, Brewerton TD, & Smith BN (2012). Comorbidity of partial and subthreshold PTSD among men and women with eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication Study: PTSD and eating disorders in men and women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(3), 307–315. 10.1002/eat.20965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Scioli ER, Galovski T, Belfer PL, & Cooper Z (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder and eating disorders: Maintaining mechanisms and treatment targets. Eating Disorders, 29(3), 292–306. 10.1080/10640266.2020.1869369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]