Abstract

The opioids are potent and widely used pain management medicines despite also possessing severe liabilities that have fueled the opioid crisis. The pharmacological properties of the opioids primarily derive from agonism or antagonism of the opioid receptors, but additional effects may arise from specific compounds, opioid receptors, or independent targets. The study of the opioids, their receptors, and the development of remediation strategies has benefitted from derivatization of the opioids as chemical tools. While these studies have primarily focused on the opioids in the context of the opioid receptors, these chemical tools may also play a role in delineating mechanisms that are independent of the opioid receptors. In this review, we describe recent advances in the development and applications of opioid derivatives as chemical tools and highlight opportunities for the future.

Introduction

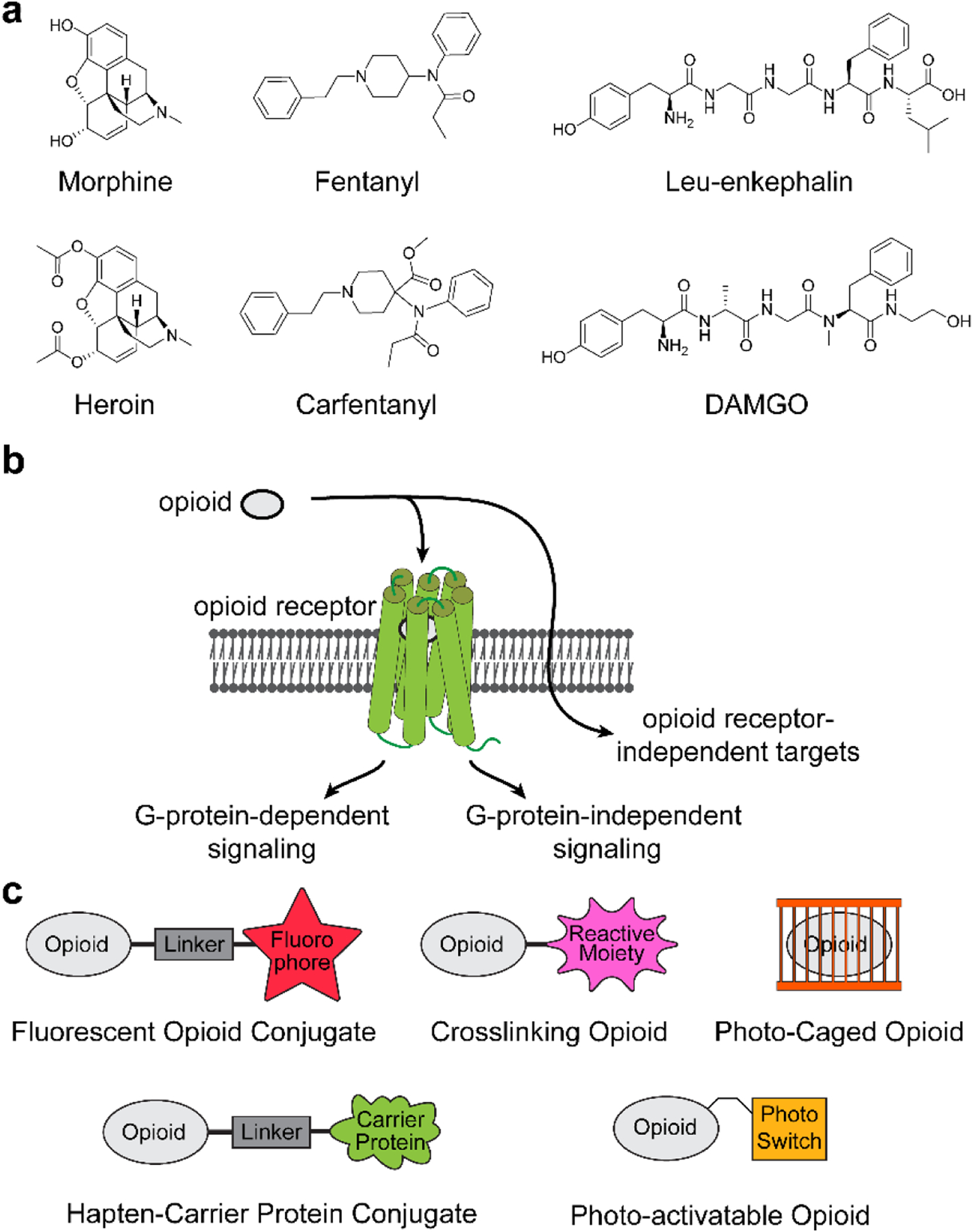

Morphine, heroin, and more recent synthetic derivatives, like fentanyl, collectively comprise the opioids that serve as a major therapeutic strategy for pain management (Figure 1a). The opioids and endogenous or engineered opioid peptides1–4 target the opioid receptors, including the mu-opioid receptor (MOR),5,6 kappa-opioid receptor (KOR),3,5,7,8 delta-opioid receptor (DOR),6,9–11 and the nociception/orphanin FQ receptor (NOR),12–15 which were discovered as the primary targets of the opioids in the latter half of the 20th century.16 The opioids achieve their analgesic properties through agonistic interactions with the opioid receptors that trigger G-protein-dependent signaling events (Figure 1b). Despite their use as pain therapies, many of the opioids also possess significant side effects, including constipation, respiratory depression, tolerance, and addiction.17 Additional phenotypes associated with opioid use include immunosuppression, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis.18,19

Figure 1. Overview of the opioids and their derivatives.

(a) Structures of common opioid ligands for the opioid receptors; (b) General schematic illustrating biased agonism of opioids at the opioid receptor; (c) Examples of opioid chemical tools highlighted herein.

The adverse side effects of the opioids may be attributed to the specific opioid, signaling events originating from the opioid receptors or their isoforms,20 or may be triggered through alternate targets and pathways. The opioids elicit discrete pharmacological profiles,21–23 implying a strong structure–activity relationship in response to the opioids.24–26 Effects of the opioids on tolerance, respiratory suppression, and acute constipation was attributed to biased activation of G-protein-independent pathways like β-arrestin 2 through the MOR,27,28 although subsequent studies in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice showed minimal alteration to these adverse effects.29,30 Opioid-induced respiratory depression, constipation, and tolerance were likewise observed on point mutagenesis of MOR to block β-arrestin activation in mouse models, further suggesting that biased agonism through β-arrestin may not be the primary mechanistic target of opioid side effects.31,32 Additionally, recent studies implicate direct effects of the opioids on toll-like receptor 433,34 and Ras homolog family member A35 signaling in an opioid receptor-independent manner. Collectively, these studies point to the need for a mechanistic understanding of the opioids and their targets to design new analgesics with reduced adverse side effects.

Mechanistic efforts to directly probe the opioid receptors have capitalized on strategies including radioligand labeling, immunohistochemistry or Western blotting with antibodies, measuring receptor response to an agonist/antagonist in cellular assays, and developing genetically tagged receptors, among other methods. While these approaches are well suited to study the action of the opioids through the opioid receptors, investigation of opioid pharmacology can benefit from alternate approaches. Direct derivatization of the opioid ligands provides a complementary approach to systematically dissect pharmacology driven by the opioid, opioid receptor, or to probe mechanistic targets of the opioids more broadly (Figure 1c). The integration of fluorophores, photo-activatable functional groups, and bio-conjugation strategies has enabled the investigation of the opioid receptors, the development of new vaccine-based strategies to mitigate side effects from the opioids and has the potential to accelerate studies of broader mechanistic targets. Herein, we review these chemical tools and highlight their versatility in the study of opioid pharmacology.

Fluorescent tools

The discovery of the opioid receptors and their direct involvement in the analgesic effects of the opioids prompted the development of chemical tools for investigating these signaling events. Early autoradiographic studies demonstrated that phenotypic response correlated with the localization of opioid receptors.36,37,38 However, the requirement for an autoradiographic exposure period precludes real time tracking of the opioid receptors during activation. Derivatization of the opioids with fluorophores is a viable strategy to gain spatial information of the opioids and their receptors by the visualization of engagement in vitro and in vivo. Fluorophore-labeled ligands can be utilized to detect ligand–receptor binding events or to study the trafficking of the receptor using imaging-based methods. Coupling of fluorescent probes for the opioids with biophysical methods such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), or bioluminescent resonance energy transfer (BRET) enables the study of receptor dynamics, oligomerization, internalization, and recruitment events.39,40 These techniques have been instrumental in measuring the behavior of opioid ligands and the regulation of the opioid receptors, such as receptor internalization, colocalization of opioid receptor isoforms, and receptor recycling. The development of fluorescent opioid receptor ligands and their biological applications was thoroughly discussed in a recent review by Drakopoulos and Deker.41 Additionally, Giakomidi et al. expansively reviewed a wide range of fluorescent opioid receptor ligands, including probes for the NOR.42 We refer the reader to these two articles for an exhaustive review of fluorescent opioid receptor ligands and their applications. Here, we primarily highlight the chemical derivatization strategies to afford fluorescent opioid probes that provide a basis for future probe development and studies for directly probing the opioid receptors and beyond.

Currently, fluorescent opioid tools fall into two broad categories: first, those that display high selectivity for an opioid receptor subtype and second, those that are non-selective for the opioid receptor to which they ligand. The first selective fluorescent opioid probe was derived from the opioid peptide enkephalin, which has high affinity for the MOR and DOR, was coupled with rhodamine to yield ([D-Ala2, Leu5])-enkephalin-Lys-Nε-Rhod (Figure 2a). Imaging studies with ([D-Ala2, Leu5])-enkephalin-Lys-Nε-Rhod revealed that the MOR and DOR form clusters on the surface of neuroblastomas without observation of receptor internalization.43, 46 Peptide-based reporters for the opioid receptors provide insight to the engagement of the opioid receptors by their natural ligands, despite contingencies with selectivity and stability. Probes developed based on the morphinan alkaloid have differential receptor selectivity, such as WA-III-62, developed by Emmerson et al. (Figure 2b).44 WA-III-62 consists of a para-nitrocinnamoylamino-dihydrocodeinone ligand coupled to a BODIPY fluorophore through a short alkyl linker and possesses high selectivity for the MOR. WA-III-62 shows an EC50 of 24 nM for MOR and an EC50 >1000 nM for other opioid receptor subtypes by a radioligand displacement assay. The probe design was later modified with a more soluble linker and fluorophore by Gentzsch and Seier et al., who substituted the short alkyl linker to BODIPY for a tetraglycine moiety with sulfo-Cy3 or sulfo-Cy5 as the fluorophore (conjugation to sulfo-Cy3 is depicted, Figure 2c).45 These chemical modifications afforded a more sensitive fluorescent probe that is wash resistant, allowing the authors to perform single molecule imaging of the MOR at physiological expression levels.

Figure 2. Chemical structures of MOR-selective fluorescent tools.

Structure of (a) ([D-Ala2, Leu5]) enkephalin-Lys-Nε-Rhod, an enkephalin derivative conjugated to rhodamine43; (b) WA-III-62, a para-nitrocinnamoylamino dihydrocodeine (CACO) ligand derivatized with a BODIPY fluorophore44; (c) CACO functionalized with Cy3 via a tetraglycine linker.45 Fluorophores are highlighted in red.

Parallel efforts to develop DOR-selective fluorescent probes have also proven fruitful. Gaudriault et al. developed a noteworthy DOR-selective probe by coupling the opioid peptide deltorphin to BODIPY to afford a probe termed ω-BH* DLT-I 5APA (Figure 3a).47 Deltrophin is an exorphin from the skin secretion of Phyllomedusa bicolor, the giant leaf frog, with strong analgesic properties by virtue of selectivity for the MOR and DOR. ω-BH* DLT-I 5APA was used to study DOR internalization in COS-7 cells that were transfected with the DOR with or without the MOR. Subsequently, Arttamangkul et al. developed TIPP-Alexa 488, a fluorescent probe with an alternative peptide sequence that possessed greater selectivity for the DOR with an inhibitory constant ratio (Ki MOR/Ki DOR) of >20,000 (MOR Ki >10 μM, DOR Ki = 0.48 nM, Figure 3b).48 The functionalization of TIPP with Alexa 488 caused the Ki to DOR to rise to 119 nM with no change in affinity to the MOR. Separately, Salvadori et al. reported antagonist peptides as opioid mimetics consisting of two unnatural peptides, 2,6-di-methyl-L-tyrosine (Dmt) and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (Tic) as the DOR binding moiety. These peptides bind tightly to the DOR with broad tolerance of different functional groups and chemical derivatives at the C-terminus. The Dmt-Tic-OH peptide showed an impressive specificity for DOR over MOR with a Ki ratio (Ki MOR/Ki DOR) of over 150,000.51 This potent DOR antagonistic peptide was converted to an imaging probe by Balboni et al., who developed H-Dmt-Tic-Glu-NH-(CH2)5-NH-(C=S)-NH-fluorescein (Figure 3c).49 Although fluorescent functionalization generally reduces the selectivity ratio between the MOR and the DOR, the Dmt-Tic pharmacophore has seen use in many probes with various amino acids and fluorophores added to the C-terminus.52,53,54,55,50 One notable example comes from Cohen et al., who coupled Dmt-Tic with Li-COR IR800CW dye and successfully imaged the DOR in lung tumors from a subcutaneous xenograft mouse model (Figure 3d).50 More recently, Sarkar et al. evaluated a range of cyclic opioid peptides bearing Dmt-Tic as the opioid receptor binding region for activity at the DOR and the MOR. Interestingly, the Dmt-Tic conjugated to cyclic peptides did not disrupt antagonism of the DOR, but did increase activity at the MOR, thus reducing the overall selectivity of these probes for the DOR.56 These studies highlight the sensitive structure–activity relationship of the opioids for their receptors and the need to characterize new chemical probes against all potential binding partners (Table 1).

Figure 3. Chemical structures of DOR selective fluorescent tools.

Structure of (a) ω-BH* DLT-I 5APA, the exorphin deltrophin functionalized with BODIPY at the C-terminus47; (b) TIPP-Alexa 488, a synthetic tetrapeptide antagonist of the DOR with Alexa 488 fluorophore48; (c) H-Dmt-Tic-Glu-NH-(CH2)5-NH-(C=S)-NH-fluorescein, a synthetic dipeptide antagonist of the DOR with a glycine and fluorescein fluorophore49; (d) Dmt-Tic-Lys-IR800CW, a synthetic dipeptide antagonist of the DOR with a fluorophore for in vivo studies.50 Fluorophores are highlighted in red.

Table 1.

Agonist potencies (pEC50) of select opioid peptides and the cyclic Dmt-Tic opioid peptides on the MOR, DOR, and KOR and antagonist potencies (pKB) of the cyclic Dmt-Tic opioid peptides on the DOR. Values shown are in nM with inactivity determined at > 10 μM peptide.56

| Peptide | MOR pEC50 | DOR pEC50 | KOR pEC50 | pKB dor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermorphin (H-Tyr-D-Ala-Phe-Gly-Tyr-Pro-Ser-NH2) | 8.66±0.1 | Inactive | Inactive | – |

| DPDPE | Inactive | 7.32±0.18 | Inactive | – |

| Dynorphin A (YGGFLRRIRPKLK) | 6.67±0.5 | 7.73±0.27 | 9.04±0.09 | – |

| Naltrindole | – | – | – | 9.89±0.12 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Lys-Phe-Phe-Asp]NH2 | 6.18±0.51 | Inactive | 6.31±0.59 | 7.37±0.29 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Lys-Phe-D-2Nal-Asp]NH2 | 6.21±0.5 | Inactive | Inactive | 7.55±0.32 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Lys-Phe-2,4F2-Phe-Asp]NH2 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 9.17±0.35 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Dap-Phe-Phe-Asp]NH2 | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 8.61±0.15 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Lys-Phe-Asp]NH2 | 6.09±0.17 | Inactive | Inactive | 9.28±0.34 |

| Dmt-Tic-c[D-Lys-Phe-Asp]-Tic-Dmt-NH2 | 6.48±0.49 | Inactive | Inactive | 8.96±0.28 |

Although the KOR possesses many known ligands,59 only a few fluorescent probes have been developed that are selective for the KOR. The first example of a fluorescent probe that displayed reasonable selectivity for the KOR came from Chang et al., who developed m-ICI-199,441-Gly4-FITC (Figure 4a).57 This molecule displays reasonable selectivity to the KOR with a Ki of 0.91 nM to KOR and a Ki of 631 nM to MOR determined by competition with radioligands in guinea pig brain membranes. The authors performed fluorescent labeling studies with this probe in mouse microglial cells at 50 μM and found that the percent of positively labeled cells could be reduced by 40 % by competition with 1 mM of the KOR-selective antagonist norbinaltorphimine. Interestingly, the percent of positively labeled cells was not reduced by competition with 500 μM β-funaltrexamine, an opioid antagonist with reported immunosuppressive effects, suggesting that the this pharmacology may arise from opioid-receptor independent mechanisms.60 Another prominent example developed by Drakopoulos et al reports the functionalization of the KOR ligand 5’-guanidinonaltrindole (5’-GNTI) to Cy3 and Cy5 dyes via a tetraglycine linker (Figure 4b–c).58 These probes have strong binding interactions with the KOR at low nanomolar concentrations and exhibit selectivity for the KOR over the DOR and the MOR with a Ki DOR/KOR or MOR/KOR ratio of ~100. The probes retained over 90 % of the fluorescent signal in CHO cells transiently expressing the KOR after a 20 min wash with cell culture media, indicative of high wash resistance.58

Figure 4. Chemical structures of KOR selective fluorescent tools.

Structure of (a) m-ICI-199,411-Gly4-FITC, a non-peptide based fluorescent probe57; (b) naltrindole, a DOR selective opioid; (c) 5’-GNTI-Cy3, a naltrindole based KOR selective fluorescent probe.58 Fluorophores are highlighted in red.

Fluorescent opioid probes that are non-selective in their agonism of specific opioid receptors may enable the discovery of broader mechanistic targets of the opioids. Archer et al. developed a probe based on naltrexamine fused to a nitrobenzoxadiazole dye (Figure 5a–b).61 Further enhancement to this probe by Arttamangkul et al, connected the naltrexamine derivative to the fluorophore with an acylimidazole containing linker (Figure 5c).62 This probe also mechanistically works by proximity labeling in which, proteins are labeled with Alexa 594 upon ligand binding. This “traceless affinity labeling” strategy was developed by Hayashi and Hamachi.63 Here, a chemical probe is designed to perform a ligand-directed labeling reaction that allows for the subsequent dissociation of the affinity module. These probes may potentially be adapted to study a related opioid, β-funaltrexamine, based on their structural similarities and covalent-based chemistries (Figure 5d). Lam et al. have also reported notable morphine-based fluorescent probes by conjugation of morphine with Cy5 to yield morphine-Cy5 (Figure 5e).64 Their findings demonstrated that functionalization at the 6’ position of morphine minimally impacts its potency and efficacy towards the opioid receptors. Imaging experiments using HEK293 cells expressing SNAP-MOR with 1 μM morphine-Cy5 could be competed by naloxone. Morphine is relatively non-selective against the opioid receptors, which may be globally illuminated by imaging studies with these fluorescent probes for morphine.

Figure 5. Chemical structures of non-isoform-selective opioid receptor tools.

Structure of (a) β-naltrexamine, an MOR and DOR agonist; (b) ASM-5–67, a naltrexamine-based probe functionalized with nitrobenzoxadiazole dye61; (c) β-funaltrexamine, an irreversible opioid antagonist; (d) NAI-A594, a naltrexamine-based probe utilizing proximity labeling to tag bio molecule with Alexa 59462; (e) morphine-Cy5, a non-opioid isoform selective morphine probe.64 Fluorophores are highlighted in red, and crosslinking moieties are highlighted in pink.

While these fluorescent probes are an asset in the investigation of the spatial localization of the opioid receptors, some limitations remain because of their inherently large structural perturbations of the parent opioid. Structural perturbation may alter the receptor specificity and recognition of the opioid ligand. Delivery of the fluorescent opioid probes, either by cellular uptake in vitro or to neuronal tissue in vivo, is also relatively challenging. These challenges may be overcome by examination of bioorthogonal chemical approaches that install a relatively small chemical handle to the opioid ligand and allow for introduction of the fluorophore after probing the biological system. Additionally, fluorescent probes are ill-suited to study the kinetics of opioid receptor signaling or for studying intercellular nociceptive transmission. This is due to the inability to precisely deliver the probe in a spatiotemporal manner. These types of studies can be accessed by a photo-pharmacological approach as discussed below.

Despite these limitations, fluorescent probes for the opioids have advanced to afford probes with high selectivity for specific opioid receptor isoforms, strong affinity to resist washing and improve the final image contrast, and installation of more soluble, brighter, and less easily photobleached fluorophores. In addition to the study of opioid receptor biology, fluorescent opioid derivatives may also be useful to track the opioids for the study of phenotypes that originate independent of the opioid receptor. For example, the opioids modulate the immune system,23 interact with the angiotensin system, and disrupt mitochondrial function, among other phenotypic outcomes.19,65 Whether these biological activities are downstream effects of stimulation of the opioid receptors, or independently activated through alternate mechanistic targets may be probed with chemical tools like these fluorescent probes, as long as these tools maintain these phenotypic effects.

Photocaged opioid probes

Chemical tools have also enabled precise spatiotemporal studies into the function of the opioid receptors by virtue of selective activation of the opioids. Functionalization of the opioids with a photocaging moiety allows for temporally precise, spatially delimited, photorelease of the opioid on short exposure to UV light (Figure 6a). Release of the opioid permits study of the kinetics of the opioid receptor’s response to stimulation by ex vivo or in vivo studies. These strategies use photopharmacology to elucidate the biological functions of the opioids and the opioid receptors, and to reduce the off-target effects of these compounds.66

Figure 6. Chemical structures of photocaged opioid peptides and alkaloids.

(a) Schematic diagram of a photocaged opioid being activated. Structure of (b) CYLE, Leu-enkephalin functionalized with a carboxy-nitrobenzyl group at the phenolic position67; (c) N-MNVOC-LE, Leu-enkephalin functionalized with a nitroveratryloxycarbonyl group at the N-terminus68; (d) CNV-Y-DAMGO, synthetic opioid peptide DAMGO with a carboxy-nitroveratryl group at the phenolic position69; (e) CNV-NLX, opioid antagonist naloxone with a carboxy-nitroveratryl group at the phenolic position70; (f) pc-morphine, opioid agonist morphine with a 7-(diethylamino)-4-(hydroxymethyl) coumarin (DEACM) moiety at the phenolic position.71 Photocaging moieties are highlighted in orange.

Towards this goal, Banghart and Sabatini have developed photoactivatable [Leu5]-enkephalin (LE) to gain insights into the spatiotemporal scale over which neuropeptides act in the central nervous system.67 For the study, they installed a carboxy-nitrobenzyl (CNB) caging group on the phenolic position of the tyrosine side chain of LE creating their probe named CYLE (Figure 6b). An in vitro functional cellular assay was performed to assess the activity of CYLE on the opioid receptors, and dose-response curves showed that CYLE did not possess agonist or antagonist activity at concentrations where LE activated the receptors in a head-to-head comparison. Photoactivation of CYLE by UV light triggered the clean release of the endogenous neuropeptide LE, with high temporal and spatial precision in neural tissue. Whole cell recordings from neurons in acute horizontal slices of the rat locus coeruleus (LC) demonstrated that the photorelease of LE produced large outward GIRK currents with an activation time constant of several hundred milliseconds. The study illustrated that the photorelease of LE activates MOR-coupled potassium channels that approach the temporal limits imposed by G-protein mediated signaling.67

Despite these insights with CYLE at the MOR, residual affinity for the DOR was retained with CYLE.67 Therefore, a modified version of the photocaged enkephalin caged with a α-methyl-6-nitroveratryloxycarbonyl (MNVOC) moiety on the N-terminal amine was developed that exhibited less residual affinity for the DOR, named N-MNVOC-LE (Figure 6c).68 This chromophore exhibited absorption at longer wavelengths and improved sensitivity to UV-LEDs resulting in faster photodecaging kinetics. An in vitro functional assay was performed to determine the residual activity and N-MNVOC-LE maintained a dramatic reduction in activity at DOR. By monitoring the electrophysiological activity from MOR-mediated potassium currents in brain slices of rat LC, the decaging of N-MNVOC-LE was observed to rapidly photolyze by a 355 nm laser generating a fast response at the MOR and DOR simultaneously, resulting in suppression of inhibitory synaptic transmission with minimal residual activity from caged N-MNVOC-LE.

Ma et al. developed a photoactivatable MOR peptide agonist using the synthetic opioid peptide DAMGO for selective engagement of the MOR.69 The authors chose a carboxy-nitroveratryl (CNV) caging group appended on the phenolic position of tyrosine in DAMGO creating CNV-Y-DAMGO (Figure 6d). This probe is decaged by a 355 nm laser and exhibits faster decaging kinetics than the MNOVC moiety. The activity of CNV-Y-DAMGO (EC50 = 1.7 μM) was evaluated using a GloSensor assay and a reduction in potency in comparison to DAMGO (EC50 = 1.5 nM) was observed. Whole cell voltage recordings in acute hippocampal brain tissues demonstrated no distinct effect on synaptic transmission whereas DAMGO suppressed inhibitory post-synaptic currents (IPSC) amplitude by 70 %. Photoactivation of CNV-Y-DAMGO with ultraviolet light resulted in rapid, transient suppression of inhibitory synaptic transmission with high spatiotemporal precision.

Photocaging of the opioid peptides has also been extended to photocaging of morphinan alkaloids. For example, naloxone derivatives have been used to selectively inhibit the opioid receptors to study the kinetics of deactivation from opioid signaling using a photocaged antagonist termed carboxynitroveratryl naloxone, CNV-NLX (Figure 6e).70 CNV-NLX was synthesized from commercially available naloxone by installing the CNV moiety on the phenolic alcohol of naloxone. CNV-NLX did not exhibit residual antagonist activity. Upon photolysis of CNV-NLX in acute slices of rat LC, antagonistic activity was observed through the rapid inhibition of outward GIRK currents induced by pre-treatment with the opioid receptor agonists DERM, DAMGO, and methadone. CNX-NLX has the potential to be extended to in vivo applications to where it may effectively block endogenous opioid actions with high spatiotemporal precision.

Recently, a photocaged-morphine (pc-morphine) was developed that utilized a coumarin chromophore to allow local light-dependent release of morphine to minimize tolerance to the analgesic effects and opioid associated side effects.71 The phenolic OH of morphine was functionalized by installing 7-(diethylamino)-4-(hydroxymethyl) coumarin (DEACM) moiety (Figure 6f). Cell based assays and the formalin animal model of pain were used to evaluate the photoactivation of pc-morphine. The photodecaging at 405 nm light occurred with a quantum yield of Φ=0.004. Intracellular calcium accumulation was assessed both in vitro and in vivo to show that photoreleased pc-morphine accumulates Ca2+ similar to that of morphine. The pc-morphine also induced GIRK mediated current activation after photolysis. The formalin mouse model of pain demonstrated the light-dependency of pc-morphine’s antinociceptive effects in both peripheral and central tissues. The remote and local activation of pc-morphine showed reduction of tolerance to analgesia and opioid-related side effects. In contrast to morphine-treated mice, naloxone administration did not exert withdrawal in mice chronically treated with pc-morphine. Overall, these results demonstrate that the use of photo-caged compounds for studies of selective opioid receptor activation and the ability to separate pain relief effects from undesirable effects associated with the existing opioid drugs.

Collectively, photocaging opioid peptides and synthetic ligands have afforded new insights to opioid receptor biology. However, a limitation of the photocage functional groups is the irreversibility of the photorelease which can be overcome by a photoswitching strategy described below.

Photoactivatable and crosslinking tools for the opioids

Incorporation of a photoswitch permits temporally precise, spatially delimited, photoactivation of the opioid from exposure to light with the additional benefit of reversibility. This photocontrol allows for the study of opioid receptor activation kinetics and, unlike irreversible photocaged opioid agonists, the study of opioid receptor deactivation kinetics. The ability to turn on or off the biological activity of an opioid with a photo-switchable functionality may also be a viable strategy to reduce the liabilities associated with opioid agonism. This photoswitching derivatization strategy of the opioids can further our understanding of opioid receptor biology and ultimately help untangle the pain-relieving effects of the opioids from their side effect liabilities.

Schönberger and Trauner described a novel approach of employing photoswitchable opioids that can be reversibly turned on and off with light to optically control MOR in overexpressing HEK293T cells.72 Photoswitchable opioid ligands provide the opportunity for controlled activation or deactivation of opioid receptors using light. Upon irradiation with light, the photoswitch undergoes photoisomerization producing a measurable change in the biological properties of the molecule (Figure 7a). The model system used by Schönberger and Trauner for this derivatization strategy was incorporating an azobenzene to fentanyl to yield photo-fentanyl (PF2) (Figure 7b). PF2 was tested in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with human MOR and with G-protein coupled inward rectifier channels (GIRK1 and GIRK2). Trans-PF2, which predominates in the dark or after irradiation with 420–480 nm light, is an effective agonist to MOR. However, the cis-PF2 isomer predominates at 360 nm and is a less active MOR agonist. The authors have shown that switching from 360 nm to blue light irradiation initiated a rapid potassium influx through the GIRK channels. This process was terminated by 360 nm light, which abolished the MOR activation. Thus, the application of PF2 lays a foundation for photopharmacology of GPCRs,74 and demonstrates that photoswitchable opioids can be used to further the investigation of the opioid receptors.

Figure 7. Chemical structures of photoactivatable opioid tools.

(a) Schematic of opioid photoswitches isomerizing between in the inactive cis conformation and the active trans conformation. Structure of (b) photo-fentanyl (PF2), an azobenzene functionalized fentanyl that photoisomerizes between the inactive cis and active trans states, respectively72; (c) photo-fentanyl pyrazole analog, a arylazopyrazole functionalized fentanyl that photoisomerizes between the inactive cis and active trans states, respectively.73 Photoswitches are highlighted in yellow.

Photoswitchable ligands are powerful chemical tools with some limitations. The applicability of photoswitchable ligands in vivo remains a challenge as diazobenzene photoswitches use UV light to photoisomerize. Therefore, the development of photoswitches that operate in the near-IR would be highly beneficial. Recently, Lahmy et al. expanded the ‘fentanyl-based photoswitch’ toolbox by replacing the azobenzene moiety with an arylazopyrazole functionality, creating photo-fentanyl pyrazole (Figure 7c).73 The pyrazole moiety possesses better photophysical properties and a red-shift absorbance for the cis-isomer. Photo-fentanyl pyrazole can photoisomerize to the active trans isomer with 528 nm light or assume the inactive cis isomer on irradiation with 365 nm light. In an IP-One accumulation assay using HEK293T cells transiently co-transfected with human MOR and hybrid G-protein Gαi5HA, photo-fentanyl pyrazole showed greater agonistic efficacy in its trans isoform (Emax = 90 %) over its cis isoform (Emax = 18 %), where the maximum receptor activation is relative to the full effect of DAMGO. These results potentially provide an avenue to applying photoswitchable opioids in vivo.

Combining chemical crosslinking strategies with the opioids afford methods to tag the targets of the opioids directly. For example, derivatization of the opioids with o-phthalaldehyde (OPTA) provides a fluorogenic moiety that can crosslink nearby lysine and cysteine residues on the opioid receptors (Figure 8a). A prominent example of this strategy comes from Le Bourdonnec et al. who developed an OPTA derivative of β-funaltrexamine (Figure 8b).75 They successfully used this probe to fluorescently label human MOR in transfected CHO cells at 1 μM concentrations. Le Bourdonnec subsequently applied this approach with the opioid naltrindole to afford the probe PNTI (Figure 8c).76 While PNTI did not display strong selectivity for a particular opioid receptor class, it did show a labeling preference for the DOR. PNTI was also successful in fluorescently labeling human DOR in transfected CHO cells.

Figure 8. Chemical structures of crosslinking opioid tools.

(a) Schematic diagram of a crosslinking opioid probe tagging an opioid receptor via ligand directed covalent chemistry. Structure of (b) OPTA-β-NA, a naltrexamine based probe with o-phthalaldehyde as the reactive moiety75; (c) PNTI, a naltrindole based probe with o-phthalaldehyde as the reactive moiety76; (d) ([D-Ala2, Leu5]) enkephalin-Lys-Nε-NAP, a photo affinity labeling probe using a phenylazide43; (e) IBNtxA, a novel naltrexamide-based analgesic with an improved side effect profile compared to morphine; (f) alkynyl-IBzA, IBNtxA-based photo affinity labeling probe with click chemistry conjugation compatibility.77 Crosslinking moieties are highlighted in pink.

Photoaffinity labeling (PAL) is an additional chemistry to covalently capture opioid interactions. The first PAL probe for the opioids were developed by Hazum et al. in 1979, who report a photo-affinity enkephalin using phenylazide as the PAL functional group (Figure 8d).43 More recently, Grinnell et al. developed azido aryl analogs of the opioid IBNtxA, the most significant being alkynyl-IBzA (Figure 8e–f).77 These IBNtxA-based probes successfully labeled opioid receptors in stably transduced CHO cells and in mouse brain samples for visualization by autoradiogram. As with other chemical tools, the use of crosslinking strategies to study opioid ligand interactions is not without caveats. Chemical derivatization of the opioid must be performed in a manner that retains the relevant phenotype. Additionally, crosslinking chemistry is susceptible to biased reactivity or non-specific labeling of proteins, which can be controlled for by use of competition experiments with the underivatized opioid. The emergence of additional labeling chemistries also presents new opportunities for development of more efficient photoaffinity probes for the opioids.78 Once a suitable crosslinking probe is identified, these chemical tools have versatile applications to the study of biomolecules targeted by the opioids.

Bioconjugates of the Opioids for Vaccination

Opioid derivatives have also been developed as tools to mitigate undesirable effects resulting in opioid use disorder (OUD). Currently, OUD is primarily treated at point of care by opioid receptor antagonists, including methadone, buprenorphine, naloxone, and naltrexone. However, overdose treatment with naloxone is become increasingly challenging due to the potency and prevalence of fentanyl and its analogs, where smaller amounts are sufficient to rapidly induce fatal overdose. An alternative strategy is to prime the immune system to respond to opioid overdose through vaccination and the generation of opioid-directed antibodies. Vaccines have promising advantages in comparison to small molecule-based pharmacotherapies. Vaccines are likely to require less frequent dosing and provide latent and longer-lasting protection in comparison to the acute administration of small molecule-based pharmacotherapies at point of care. There are comprehensive reviews on various opioid vaccines reported in the literature.79–84 Here, we focus on the derivatization of the opioids for bioconjugation during vaccine development.

Opioid vaccines consist of three components: the hapten, the conjugate protein, and an adjuvant. As small molecules like the opioids are generally too small to stimulate the immune system alone and therefore not immunogenic, the small molecule is typically chemically conjugated to an immunogenic carrier protein through a linker to display the antigenic motif. The immunoconjugates are then mixed or adsorbed on adjuvants or other particle-based delivery systems to afford the vaccine. Once injected, the vaccine will stimulate the immune system to produce opioid-specific antibodies. These opioid-specific antibodies act to reduce or slow opioid distribution to the brain by selectively binding to the free opioid, and thereby sequestering the compound from the blood stream and reducing the concentration of unbound opioid that can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to reach the brain.83 To date, opioid vaccines have shown great success in preclinical evaluation and a few candidates have now progressed to clinical trials (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of opioid vaccines in preclinical and clinical trials.79

| Drug | Preclinical trials | Clinical trials |

|---|---|---|

| Oxycodone | Oxy-TT | Oxy-(Gly)4-sKLH |

| Heroin | Her-KLH, Mor-KLH | None |

| Heroin-HIV-I (H2) vaccine | ||

| Morphine | KLH-6-SM | None |

| M(Gly)-4-KLH | ||

| Fentanyl | FEN-CRM | none |

| Fentanyl-TT |

The first studies demonstrating the ability of vaccines to generate antibodies against the opioids were conducted by Spector and Parker in the early 1970s (Figure 9a).85 The authors reported the development of a vaccine against morphine and the antibodies produced by vaccinated rabbits were used in a radioimmunoassay for morphine. In further establishment of viable vaccination against the opioids, Hill et al. studied the rate of morphine clearance in rabbits immunized against morphine-6-hemisuccinate bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Figure 9b).86 The rate of morphine clearance was significantly slower in immunized animals than in normal animals after 24 h, which was attributed to the relative antigen-binding capacity and antibody concentration. The Kosten group additionally developed a vaccine by conjugating 6-succinylmorphine to lysine displayed on the immunogen keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), called KLH-6-SM (Figure 9c).87 Preclinical studies showed an increase in the anti-morphine antibody levels in vaccinated rats, which was sustained through 24 weeks. Levels of morphine in the brain of vaccinated rats were reduced by 25%, which corresponded to an expected attenuation in behavioral effects. Thus, the KLH-6-SM vaccine is a potential candidate to treat opioid dependence to morphine and may also provide antibodies as diagnostics for morphine levels in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 9. Chemical structures of morphine-based protein bioconjugates.

Structure of (a) morphine conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA) from the phenolic position85; (b) morphine conjugated to BSA from the 6’ position via a succinate86; (c) morphine conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) from the 6’ position via a succinate.87

Although heroin is rapidly metabolized (Figure 10a), the development of a vaccine directly against heroin has the potential advantage of generating antibodies against heroin and its metabolic intermediates 6-AM and morphine, simultaneously. The first proof-of-concept that immunization to morphine would provide cross immunization to heroin was demonstrated in 1974 in studies with rhesus monkeys immunized to morphine-based hapten conjugated to BSA, which resulted in attenuated self-administration of heroin behavior.94 More recently, Anton and Leff developed a bivalent vaccine against morphine, which produced high antibody titers that was functional against both morphine and heroin in rats (Figure 10b).90 To generate a so called ‘dynamic’ heroin vaccine, Schlosburg et al. functionalized the bridge-head nitrogen of heroin with maleimide for conjugation to BSA or KLH (Figure 10c).91 Excitingly, the vaccination strategy generated antibodies with excellent binding for heroin, 6-AM, and morphine, while functionalizing morphine from the same amine yielded only morphine immunization. An efficient blockade of heroin activity and prevention of drug abuse was also observed in rats treated with this vaccine. In another study, morphine-conjugate vaccines have shown to effectively reduce the behavioral effects of heroin.95 The authors developed a morphine-based hapten by installing a tetraglycine linker at the C6 position and conjugated to KLH. Rats vaccinated with morphine conjugates to KLH produced a high titer of antibodies with strong affinity for heroin, 6-AM and morphine. The vaccinated rats retained these three opioids in their plasma and thus opioid distribution to the brain and heroin-induced locomotor sensitization were both reduced. Later, Bremer et al. developed a heroin tetanus toxin (TT) conjugate vaccine that was more efficient than an analogous maleimide based conjugate at immunization and reducing response to heroin by >15-fold (Figure 10d).92 The immunization from this lead vaccine was efficacious in mice and non-human primate models over a wide range of heroin doses and durable for over eight months.

Figure 10. Metabolism of heroin and structure of conjugates for immunization to heroin.

(a) Schematic of the known drug metabolic pathway of heroin.88,89 Structure of (b) 6-acetylmorphine conjugated to tetanus toxoid via a polyalkylamide linker90; (c) heroin or morphine conjugated to KLH91; (d) heroin conjugated to tetanus toxoid92; (e) morphine conjugated to tetatus toxoid via a PEGylated maleimide linker.93 Additionally, the V2 loop of HIV-1 glycoprotein 120 envelope protein was cloned into the tetanus toxoid.

Jalah et al. have developed a combination vaccine for simultaneous treatment of heroin addiction and prevention of HIV-1 infection among injection drug users. In this study, previously reported heroin analog (MorHap) containing PEGylated maleimide crosslinker conjugated to TT96, was additionally modified with a 42 amino acid synthetic peptide V2 loop from A/E strain of HIV-1 glycoprotein120 envelope protein (Figure 10e).93 High end-point titers of antibodies for both MorHap and HIV were observed. Significant inhibition of heroin-induced antinociception effect and hyper-locomotion in immunized mice. Such dual targeting vaccines will be beneficial for treatment of OUD and HIV infection in opioid drug users.

With the increasing number of fentanyl driven fatalities, focused efforts towards a fentanyl vaccine are of growing importance. In 2016, Bremer et al. developed a fentanyl-tetanus toxoid (TT) conjugate vaccine that reduced antinociception and protected mice from lethal doses of fentanyl (Figure 11a–b).97 The mouse serum antibodies bound fentanyl with single digit nanomolar affinity. The vaccine produced up to 33-fold antinociceptive potency shift for fentanyl and a 9-fold shift for α-methylfentanyl in mice. Furthermore, the same group also showed the effectiveness of the fentanyl TT vaccine by using a fentanyl-vs-food choice procedure in rats.99 The vaccine shifted intravenous fentanyl antinociceptive potency by approximately 22-fold, which was as effective as naltrexone, the clinically approved treatment for opioid overdose. Separately, Raleigh et al. identified a fentanyl vaccine, which consists of a fentanyl-based hapten conjugated to either the native KLH carrier protein or GMP-grade subunit KLH (sKLH), called F-KLH and F-sKLH respectively (Figure 11c).98 The F-KLH was effective in mice and rats in reducing the fentanyl-induced hotplate antinociception by 5.4 fold and in rats reduced fentanyl distribution to the brain. Additionally, immunization with F-sKLH in rats reduced respiratory depression with increasing doses of fentanyl. Another study by Tenny et al. showed the effectiveness and selectivity of a fentanyl-tetanus toxoid conjugate vaccine in altering the behavioral effects of fentanyl in male rhesus monkeys.100 The vaccine showed significant shift in fentanyl potency and antinociception > 10-fold. Antibody immune response improved to approximately 3–4 nM for fentanyl.

Figure 11. Chemical structures of fentanyl protein bioconjugates.

Structure of (a) the potent opioid agonist fentanyl; (b) fentanyl conjugated to tetanus toxoid via short alkyl linker97; (c) fentanyl conjugated to KLH or GMP-grade subunit KLH via a tetraglycine linker.98

Vaccination strategies may be limited by the specificity against an individual opioid with activity across very similar analogs, which may not be responsive to the full range of opioid ligands. Illicit opioids may contain a complex mixture of opioids, and thus an individual opioid vaccine may not be fully protective. Therefore, development of vaccination strategies that provide broad spectrum immunity is of future importance. Beyond clinical applicability, these opioid tools could serve to provide new opioid antibodies that can find use in confocal microscopy, Western blotting, or other analytical methods. These opioid bioconjugates may therefore provide powerful tools to study opioid pharmacology in addition to a valuable strategy to address the opioid crisis.

Future Directions

In this review, we have highlighted chemical derivatization strategies to collectively afford fluorescent, photoactivatable, and bioconjugation tools for the opioids. These technological advances in opioid chemical tools have been largely driven by efforts to probe or treat activity through the opioid receptors. Going forward, the development of new tools or application of those in hand will enable delineation of opioid pharmacology that are dependent or independent of the opioid receptor. Chemical tools for the opioids may also provide a foundation for the development of assays to screen for desirable or undesirable effects of small molecules with activity in the central nervous system, such as in the development of early-stage screening assays for analgesic effects or activation of abuse markers. The continued development of opioid probes by integration of new fluorescent probes, proximity labeling strategies, and antibodies, combined with powerful technologies like single molecule imaging or chemical proteomics will shed new light on the opioids, their receptors, and beyond.

Highlights.

Fluorescent probes to track spatial localization of the opioids are an asset in the investigation of the opioid receptors and independent targets.

Photoactivatable, photocaged, and crosslinking opioids are useful for kinetic studies and measuring spatiotemporal interactions of the opioids.

Opioid bioconjugates have successfully generated vaccines that are in preclinical and clinical trials. These antibodies could also have impact on variety of bioanalytical methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Miyamoto, H. Lloyd, F. Kabir, and N. Curnutt for their advice and helpful discussions. Support from NIH NIDA (DP1DA046586) and Harvard University are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hughes J et al. Identification of two related pentapeptides from the brain with potent opiate agonist activity. Nature 258, 577–579, doi: 10.1038/258577a0 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox BM, Goldstein A & Hi CH Opioid activity of a peptide, beta-lipotropin-(61–91), derived from beta-lipotropin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 73, 1821–1823, doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.1821 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein A, Tachibana S, Lowney LI, Hunkapiller M & Hood L Dynorphin-(1–13), an extraordinarily potent opioid peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 76, 6666–6670, doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.12.6666 (1979). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zadina JE, Hackler L, Ge L-J & Kastin AJ A potent and selective endogenous agonist for the μ-opiate receptor. Nature 386, 499–502, doi: 10.1038/386499a0 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin WR, Eades CG, Thompson JA, Huppler RE & Gilbert PE The effects of morphine- and nalorphine- like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 197, 517–532 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord JAH, Waterfield AA, Hughes J & Kosterlitz HW Endogenous opioid peptides: multiple agonists and receptors. Nature 267, 495–499, doi: 10.1038/267495a0 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavkin C, James IF & Goldstein A Dynorphin is a specific endogenous ligand of the kappa opioid receptor. Science 215, 413–415, doi: 10.1126/science.6120570 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitchen I, Slowe SJ, Matthes HW & Kieffer B Quantitative autoradiographic mapping of mu-, delta- and kappa-opioid receptors in knockout mice lacking the mu-opioid receptor gene. Brain Res. 778, 73–88, doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00988-8 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans CJ, Keith DE, Morrison H, Magendzo K & Edwards RH Cloning of a Delta Opioid Receptor by Functional Expression. Science 258, 1952–1955, doi:doi: 10.1126/science.1335167 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kieffer BL, Befort K, Gaveriaux-Ruff C & Hirth CG The delta-opioid receptor: isolation of a cDNA by expression cloning and pharmacological characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 89, 12048–12052, doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12048 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kieffer BL Recent advances in molecular recognition and signal transduction of active peptides: Receptors for opioid peptides. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 15, 615–635, doi: 10.1007/bf02071128 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bunzow JR et al. Molecular cloning and tissue distribution of a putative member of the rat opioid receptor gene family that is not a μ, δ or κ opioid receptor type. FEBS Lett. 347, 284–288, doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00561-3 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollereau C et al. ORL1, a novel member of the opioid receptor family. FEBS Lett. 341, 33–38, doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80235-1 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meunier J-C et al. Isolation and structure of the endogenous agonist of opioid receptor-like ORL1 receptor. Nature 377, 532–535, doi: 10.1038/377532a0 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinscheid RK et al. Orphanin FQ: a neuropeptide that activates an opioidlike G protein-coupled receptor. Science 270, 792–794, doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.792 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raynor K et al. Pharmacological characterization of the cloned kappa-, delta-, and mu-opioid receptors. Mol. Pharmacol 45, 330–334 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mercadante S, Arcuri E & Santoni A Opioid-Induced Tolerance and Hyperalgesia. CNS Drugs 33, 943–955, doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00660-0 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng J et al. Morphine-induced microglial immunosuppression via activation of insufficient mitophagy regulated by NLRX1. Journal of Neuroinflammation 19, doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02453-7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunha-Oliveira T et al. Street heroin induces mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in rat cortical neurons. J. Neurochem 101, 543–554, doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04406.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasternak GW & Pan Y-X Mu Opioids and Their Receptors: Evolution of a Concept. Pharmacol. Rev 65, 1257–1317, doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hull LC et al. The Effect of Protein Kinase C and G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase Inhibition on Tolerance Induced by μ-Opioid Agonists of Different Efficacy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 332, 1127–1135, doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.161455 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillis A et al. Critical Assessment of G Protein-Biased Agonism at the μ-Opioid Receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci 41, 947–959, doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.09.009 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenstein TK The Role of Opioid Receptors in Immune System Function. Front. Immunol 10, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02904 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X et al. Morphine activates neuroinflammation in a manner parallel to endotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 109, 6325–6330, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200130109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C-C et al. β-Funaltrexamine Displayed Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Effects in Cells and Rat Model of Stroke. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, 3866, doi: 10.3390/ijms21113866 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutchinson MR et al. Opioid Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Contributes to Drug Reinforcement. J. Neurosci 32, 11187–11200, doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0684-12.2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin F-T, Lefkowitz RJ & Caron MG μ-Opioid receptor desensitization by β-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature 408, 720–723, doi: 10.1038/35047086 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raehal KM, Walker JKL & Bohn LM Morphine Side Effects in β-Arrestin 2 Knockout Mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 314, 1195–1201, doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087254 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kliewer A et al. Morphine‐induced respiratory depression is independent of β-arrestin2 signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol 177, 2923–2931, doi: 10.1111/bph.15004 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koblish M et al. TRV0109101, a G Protein-Biased Agonist of the μ-Opioid Receptor, Does Not Promote Opioid-Induced Mechanical Allodynia following Chronic Administration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 362, 254–262, doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.241117 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kliewer A et al. Phosphorylation-deficient G-protein-biased μ-opioid receptors improve analgesia and diminish tolerance but worsen opioid side effects. Nat. Commun 10, doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08162-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miess E et al. Multisite phosphorylation is required for sustained interaction with GRKs and arrestins during rapid μ-opioid receptor desensitization. Science Signaling 11, eaas9609, doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aas9609 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutchinson MR et al. Evidence that opioids may have toll-like receptor 4 and MD-2 effects. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 24, 83–95, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.004 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabr MM et al. Interaction of Opioids with TLR4—Mechanisms and Ramifications. Cancers 13, 5274, doi: 10.3390/cancers13215274 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu Z, Jin S, Tian S & Wang Z Morphine stimulates cervical cancer cells and alleviates cytotoxicity of chemotherapeutic drugs via opioid receptor-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 10, doi: 10.1002/prp2.1016 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.May CN, Dashwood MR, Whitehead CJ & Mathias CJ Differential cardiovascular and respiratory responses to central administration of selective opioid agonists in conscious rabbits: correlation with receptor distribution. Br. J. Pharmacol 98, 903–913, doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb14620.x (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuhar MJ Histochemical localization of opiate receptors and opioid peptides. Fed. Proc 37, 153–157 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuhar MJ & Uhl GR Histochemical localization of opiate receptors and the enkephalins. Adv. Biochem. Psychopharmacol 20, 53–68 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuder KJ & Kieć-Kononowicz K Fluorescent GPCR ligands as new tools in pharmacology-update, years 2008-early 2014. Curr. Med. Chem 21, 3962–3975, doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140826120058 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soave M, Briddon SJ, Hill SJ & Stoddart LA Fluorescent ligands: Bringing light to emerging GPCR paradigms. Br. J. Pharmacol 177, 978–991, doi: 10.1111/bph.14953 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drakopoulos A & Decker M Development and Biological Applications of Fluorescent Opioid Ligands. ChemPlusChem 85, 1354–1364, doi: 10.1002/cplu.202000212 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giakomidi D, Bird MF, Guerrini R, Calo G & Lambert DG Fluorescent opioid receptor ligands as tools to study opioid receptor function. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 113, doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2021.107132 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hazum E, Chang KJ, Shechter Y, Wilkinson S & Cuatrecasas P Fluorescent and photo-affinity enkephalin derivatives: preparation and interaction with opiate receptors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 88, 841–846, doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91485-2 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emmerson PJ et al. Synthesis and characterization of 4,4-difluoro-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene (BODIPY)-labeled fluorescent ligands for the mu opioid receptor. Biochem. Pharmacol 54, 1315–1322, doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00374-2 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gentzsch C et al. Selective and Wash-Resistant Fluorescent Dihydrocodeinone Derivatives Allow Single-Molecule Imaging of μ-Opioid Receptor Dimerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 59, 5958–5964, doi: 10.1002/anie.201912683 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hazum E, Chang KJ & Cuatrecasas P Opiate (Enkephalin) receptors of neuroblastoma cells: occurrence in clusters on the cell surface. Science 206, 1077–1079, doi: 10.1126/science.227058 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gaudriault G, Nouel D, Farra CD, Beaudet A & Vincent J-P Receptor-induced Internalization of Selective Peptidic μ and Δ Opioid Ligands. J. Biol. Chem 272, 2880–2888, doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2880 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arttamangkul S, Alvarez-Maubecin V, Thomas G, Williams JT & Grandy DK Binding and Internalization of Fluorescent Opioid Peptide Conjugates in Living Cells. Mol. Pharmacol 58, 1570–1580, doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1570 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balboni G et al. Highly Selective Fluorescent Analogue of the Potent δ-Opioid Receptor Antagonist Dmt-Tic. J. Med. Chem 47, 6541–6546, doi: 10.1021/jm040128h (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen AS et al. Delta-Opioid Receptor (δOR) Targeted Near-Infrared Fluorescent Agent for Imaging of Lung Cancer: Synthesis and Evaluation In Vitro and In Vivo. Bioconjugate Chem. 27, 427–438, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00516 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salvadori S et al. Delta opioidmimetic antagonists: prototypes for designing a new generation of ultraselective opioid peptides. Mol. Med 1, 678–689 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li T et al. Potent Dmt-Tic Pharmacophoric δ- and μ-Opioid Receptor Antagonists. J. Med. Chem 48, 8035–8044, doi: 10.1021/jm050377l (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vázquez ME et al. 6-N,N-Dimethylamino-2,3-naphthalimide: A New Environment-Sensitive Fluorescent Probe in δ- and μ-Selective Opioid Peptides. J. Med. Chem 49, 3653–3658, doi: 10.1021/jm060343t (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Josan JS et al. Solid-Phase Synthetic Strategy and Bioevaluation of a Labeled δ-Opioid Receptor Ligand Dmt-Tic-Lys for In Vivo Imaging. Org. Lett 11, 2479–2482, doi: 10.1021/ol900200k (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huynh AS et al. Tumor Targeting and Pharmacokinetics of a Near-Infrared Fluorescent-Labeled δ-Opioid Receptor Antagonist Agent, Dmt-Tic-Cy5. Mol. Pharmaceutics 13, 534–544, doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00760 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarkar A et al. Design, Synthesis and Functional Analysis of Cyclic Opioid Peptides with Dmt-Tic Pharmacophore. Molecules 25, 4260, doi: 10.3390/molecules25184260 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang A-C et al. Arylacetamide-Derived Fluorescent Probes: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Direct Fluorescent Labeling of κ Opioid Receptors in Mouse Microglial Cells. J. Med. Chem 39, 1729–1735, doi: 10.1021/jm950813b (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drakopoulos A et al. Investigation of Inactive-State κ Opioid Receptor Homodimerization via Single-Molecule Microscopy Using New Antagonistic Fluorescent Probes. J. Med. Chem 63, 3596–3609, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02011 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brust TF Biased Ligands at the Kappa Opioid Receptor: Fine-Tuning Receptor Pharmacology. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 271, 115–135, doi: 10.1007/164_2020_395 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis RL, Das S, Thomas Curtis J & Stevens CW The opioid antagonist, β-funaltrexamine, inhibits NF-κB signaling and chemokine expression in human astrocytes and in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol 762, 193–201, doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.040 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Archer S, Medzihradsky F, Seyed-Mozaffari A & Emmerson PJ Synthesis and characterization of 7-nitrobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD)-labeled fluorescent opioids. Biochem. Pharmacol 43, 301–306, doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90292-q (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arttamangkul S et al. Visualizing endogenous opioid receptors in living neurons using ligand-directed chemistry. eLife 8, doi: 10.7554/elife.49319 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayashi T & Hamachi I Traceless Affinity Labeling of Endogenous Proteins for Functional Analysis in Living Cells. Acc. Chem. Res 45, 1460–1469, doi: 10.1021/ar200334r (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lam R et al. Fluorescently Labeled Morphine Derivatives for Bioimaging Studies. J. Med. Chem 61, 1316–1329, doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01811 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Király K et al. Shedding Light on the Pharmacological Interactions between μ-Opioid Analgesics and Angiotensin Receptor Modulators: A New Option for Treating Chronic Pain. Molecules 26, 6168, doi: 10.3390/molecules26206168 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gazerani P Shedding light on photo-switchable analgesics for pain. Pain Manag. 7, 71–74, doi: 10.2217/pmt-2016-0039 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Banghart Matthew R. & Sabatini Bernardo L. Photoactivatable Neuropeptides for Spatiotemporally Precise Delivery of Opioids in Neural Tissue. Neuron 73, 249–259, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.016 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Banghart MR, He XJ & Sabatini BL A Caged Enkephalin Optimized for Simultaneously Probing Mu and Delta Opioid Receptors. ACS Chem. Neurosci 9, 684–690, doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00485 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma X, He XJ & Banghart MR A caged DAMGO for selective photoactivation of endogenous mu opioid receptors. bioRxiv, 2021.2009.2013.460181, doi: 10.1101/2021.09.13.460181 (2021). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Banghart MR, Williams JT, Shah RC, Lavis LD & Sabatini BL Caged Naloxone Reveals Opioid Signaling Deactivation Kinetics. Mol. Pharmacol 84, 687, doi: 10.1124/mol.113.088096 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.López-Cano M et al. Remote local photoactivation of morphine produces analgesia without opioid-related adverse effects. Br. J. Pharmacol n/a, doi: 10.1111/bph.15645 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schönberger M & Trauner D A photochromic agonist for μ-opioid receptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 53, 3264–3267, doi: 10.1002/anie.201309633 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lahmy R et al. Photochromic Fentanyl Derivatives for Controlled μ-Opioid Receptor Activation. Chem. – Eur. J 28, e202201515, doi: 10.1002/chem.202201515 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lerch MM, Hansen MJ, van Dam GM, Szymanski W & Feringa BL Emerging Targets in Photopharmacology. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 55, 10978–10999, doi: 10.1002/anie.201601931 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Le Bourdonnec B et al. Reporter Affinity Labels: An o-Phthalaldehyde Derivative of β-Naltrexamine as a Fluorogenic Ligand for Opioid Receptors. J. Med. Chem 43, 2489–2492, doi: 10.1021/jm000138s (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Le Bourdonnec B et al. Covalently Induced Activation of the δ Opioid Receptor by a Fluorogenic Affinity Label, 7’-(Phthalaldehydecarboxamido)naltrindole (PNTI). J. Med. Chem 44, 1017–1020, doi: 10.1021/jm010004u (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Grinnell SG et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Azido Aryl Analogs of IBNtxA for Radio-Photoaffinity Labeling Opioid Receptors in Cell Lines and in Mouse Brain. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol 41, 977–993, doi: 10.1007/s10571-020-00867-6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.West AV & Woo CM Photoaffinity Labeling Chemistries Used to Map Biomolecular Interactions. Isr. J. Chem 63, e202200081, doi: 10.1002/ijch.202200081 (2023). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Celik M & Fuehrlein B A Review of Immunotherapeutic Approaches for Substance Use Disorders: Current Status and Future Prospects. Immunotargets Ther. 11, 55–66, doi: 10.2147/itt.s370435 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kinsey B Vaccines against drugs of abuse: where are we now? Ther. Adv. Vaccines 2, 106–117, doi: 10.1177/2051013614537818 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bremer PT & Janda KD Conjugate Vaccine Immunotherapy for Substance Use Disorder. Pharmacol. Rev 69, 298, doi: 10.1124/pr.117.013904 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Olson ME & Janda KD Vaccines to combat the opioid crisis. EMBO Rep 19, 5–9, doi: 10.15252/embr.201745322 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pravetoni M & Comer SD Development of vaccines to treat opioid use disorders and reduce incidence of overdose. Neuropharmacol. 158, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.06.001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scendoni R, Bury E, Ribeiro ILA, Cameriere R & Cingolani M Vaccines as a preventive tool for substance use disorder: A systematic review including a meta-analysis on nicotine vaccines’ immunogenicity. Hum. Vaccines Immunother, 2140552, doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2140552 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spector S & Parker CW Morphine: Radioimmunoassay. Science 168, 1347–1348, doi: 10.1126/science.168.3937.1347 (1970). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hill JH, Wainer BH, Fitch FW & Rothberg RM Delayed Clearance of Morphine from the Circulation of Rabbits Immunized with Morphine-6-Hemisuccinate Bovine Serum Albumin. J. Immunol 114, 1363 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kosten TA et al. A morphine conjugate vaccine attenuates the behavioral effects of morphine in rats. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 45, 223–229 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boerner U The metabolism of morphine and heroin in man. Drug Metab Rev 4, 39–73, doi: 10.3109/03602537508993748 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garrett ER & Gürkan T Pharmacokinetics of morphine and its surrogates IV: Pharmacokinetics of heroin and its derived metabolites in dogs. J. Pharm. Sci 69, 1116–1134, doi: 10.1002/jps.2600691002 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anton B & Leff P A novel bivalent morphine/heroin vaccine that prevents relapse to heroin addiction in rodents. Vaccine 24, 3232–3240, doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.047 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schlosburg JE et al. Dynamic vaccine blocks relapse to compulsive intake of heroin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 110, 9036–9041, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219159110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bremer PT et al. Development of a Clinically Viable Heroin Vaccine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 8601–8611, doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03334 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Torres OB et al. Heroin-HIV-1 (H2) vaccine: induction of dual immunologic effects with a heroin hapten-conjugate and an HIV-1 envelope V2 peptide with liposomal lipid A as an adjuvant. npj Vaccines 2, doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0013-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bonese KF, Wainer BH, Fitch FW, Rothberg RM & Schuster CR Changes in heroin self-administration by a rhesus monkey after morphine immunisation. Nature 252, 708–710, doi: 10.1038/252708a0 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raleigh MD, Pravetoni M, Harris AC, Birnbaum AK & Pentel PR Selective Effects of a Morphine Conjugate Vaccine on Heroin and Metabolite Distribution and Heroin-Induced Behaviors in Rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 344, 397, doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201194 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jalah R et al. Efficacy, but Not Antibody Titer or Affinity, of a Heroin Hapten Conjugate Vaccine Correlates with Increasing Hapten Densities on Tetanus Toxoid, but Not on CRM197 Carriers. Bioconjugate Chem. 26, 1041–1053, doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00085 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bremer PT et al. Combatting Synthetic Designer Opioids: A Conjugate Vaccine Ablates Lethal Doses of Fentanyl Class Drugs. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 55, 3772–3775, doi: 10.1002/anie.201511654 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Raleigh MD et al. A Fentanyl Vaccine Alters Fentanyl Distribution and Protects against Fentanyl-Induced Effects in Mice and Rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 368, 282–291 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Townsend EA et al. Conjugate vaccine produces long-lasting attenuation of fentanyl vs. food choice and blocks expression of opioid withdrawal-induced increases in fentanyl choice in rats. Neuropsychopharmacol. 44, 1681–1689 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tenney RD et al. Vaccine blunts fentanyl potency in male rhesus monkeys. Neuropharmacol. 158, 107730, doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107730 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]