Abstract

Primary splenic lymphomas are rare with the majority of lymphomas in spleen being secondary to an extra-splenic lymphoma. We aimed to analyze the epidemiological profile of the splenic lymphoma and review the literature. This was a retrospective study including all splenectomies and splenic biopsies from 2015 to September 2021. All the cases were retrieved from Department of Pathology. Detailed histopathological, clinical and demographic evaluation was done. All the lymphomas were classified according to WHO 2016 classification. A total of 714 splenectomies were performed for a variety of benign causes, as part of tumor resections and for the diagnosis of lymphoma. Few core biopsies were also included. A total of 33 lymphomas diagnosed in the spleen, primary splenic lymphomas constituted 84.84% (n = 28) of the cohort with 5 (15.15%) having the primary site elsewhere. The primary splenic lymphomas constituted 0.28% of all the lymphomas arising at various sites. Adult population (19–65 years) formed the bulk (78.78%) with a slight male preponderance. Splenic marginal zone lymphomas (n = 15, 45.45%) comprised of major proportion of cases followed by primary splenic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 4, 12.12%). Splenectomy was the main course of treatment for SMZL with a good overall outcome, with chemotherapy ± radiotherapy forming the mainstay in other lymphomas. Lymphomas in spleen can be infiltrative or a primary, hence proper clinic-radiological and pathological evaluation is required. Appropriate management is guided by the precise and detailed evaluation by the pathologist, requiring understanding of the same.

Keywords: Primary splenic lymphomas, Splenic marginal zone lymphomas, Splenectomy

Introduction

The spleen, a reticuloendothelial organ, serves as a clearance site for abnormal cells and plays a role in extramedullary hematopoiesis. It can serve as culture medium for the proliferation of hematopoietic cells, leading to development of hematological malignancy. However, primary splenic lymphomas are rare [1]. Most of the lymphomas in spleen tend to be infiltration of a lymphoma arising elsewhere, wherein 30–40% of Non-Hodgkin lymphomas manifest splenic involvement during their course. The majority of the splenectomies performed for splenomegaly, 36.5–57%, are diagnosed as lymphoid neoplasm [2].

Splenic tumors can mainly be divided into lymphoid and non-lymphoid tumors, including vascular and metastatic tumor. Constituting about 1% of all Non-Hodgkin lymphomas, primary splenic lymphomas (PSL) constitute of less than 2% of all lymphomas [3]. The tumors may manifest as splenomegaly, upper left abdominal discomfort, or abdominal pain. The vague symptomatology is shared with abscesses, traumatic injuries, emboli and other infections. Pancytopenia may also be noted with increased scavenging activity of spleen. Splenomegaly is commonly observed; however, the normal size of spleen does not rule out the neoplastic involvement. Diagnostic splenectomies earlier done for staging of lymphomas for the primary diagnosis have been now replaced by splenic biopsies and radiological investigations. Though the highly vascular nature of spleen renders the biopsy procedure to be of a fair risk; however, careful and cautious approach may help the cause. Though lymphomas predominantly home in the splenic white pulp; red pulp involvement can be seen a variety of lymphomas (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Preferential involvement of red [A] and white pulp [B] by different lymphomas DLBCL-Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, PTCL- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, CLL/SLL-Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, AITL-Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Table1.

Involvement of Lymphoma in different compartment of Spleen

| Lymphoma lineage | Predominant white pulp involvement | Predominant red pulp involvement | Both-red and white pulp involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell |

CLL/ SLL Lymphoblastic lymphoma Mantle cell Follicular SMZL Nodal marginal zone |

Hairy cell leukemia Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma Hairy cell leukemia, variant |

Burkitt DLBCL SMZL CLL/SLL |

| T- and NK-cell | ALCL |

T-cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia T-prolymphocytic leukemia Aggressive NK-cell leukemia Adult T-cell leukemia ENKTCL Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma |

Mycosis fungoides PTCL, NOS AITL |

CLL/SLL Chronic lymphocytic Leukaemia/Small lymphocytic Lymphoma, DLBCL Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, SMZL Splenic Marginal Zone lymphoma, ALCL Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma, PICL Peripheral T cell Lymphoma, AITL Angio Immunoblastic T cell Lymphoma, ENKTL Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma

The low prevalence and detection of primary splenic lymphomas can be hypothesized due to the late occurrence of symptoms, lack of a distinct immunophenotype differentiating from the nodal counterparts and the phagocytic cells predominant in spleen which control the proliferation of neoplastic cells With the current limited data regarding the distribution and demography of splenic lymphomas in the Indian subcontinent, we aimed to analyze the epidemiological profile of the lymphomas reported in spleen.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective study including all splenectomies and lymphoma related splenic biopsies done at our institute from 2015 to October 2021 were included. The cases were retrieved from the database of Department of Pathology. Clinical parameters like age, sex, symptomatology along with follow-up data was obtained by retrospective chart review of department of Hematology and Dr. B.R.A. Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital. Detail Histomorphological parameter like distribution of red pulp and white pulp, lymphoid follicle expansion, Coalescence of white pulp, presence of lymphoid nodule in red pulp and extra-medullary haematopoiesis. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CD3, CD20, CD5, CD23, CyclinD1, Bcl2, BCl6 and CD10 done in morphologically suspected cases of lymphoma. IHC was performed by manual method. Imimmunophenotypical features were reviewed along with the hematological investigations. The cases were classified according to the WHO 2016 classification.

Criteria for the diagnosis of primary splenic lymphoma (based on previous studies) included: [4]

-

i.

Presence of splenomegaly documented clinically (palpable spleen), radiologically (length more than 12 cm in adults) or on laparotomy (weight of spleen more than 400 g)

-

ii.

Lymphomas arising in spleen or primarily confined to spleen

-

iii.

Absence of significant or generalised lymphadenopathy

The data collection was done as part of projects and ethical clearance was taken for the projects (IEC-458/07.09.2018, RP-4/2018, and IEC-431/02.09.2016.RP-7/2016).

Results

A total of 714 splenectomies were performed for a variety of benign causes, as part of tumor resections and for the diagnosis of lymphoma; however, only a minor proportion could be part of our study group. Few core biopsies (n = 5) were also included. A total of 33 lymphomas were diagnosed in spleen, with 5 (15.15%) having the primary site elsewhere like nodal or other sites such as stomach or colon. The primary splenic lymphomas constituted 0.58% of all the lymphomas (n = 4115) arising at various sites as indicated in our previous study for the years 2015–2019 [5].

Middle-aged adult population (19–65 years) formed the bulk (78.78%) followed by elderly > 65 years (9.09%) and children and adolescents < 19 years (12.12%). A male predominance was noted, with a male to female ratio of 1.2:1. Majority of the patients presented with anemia, presence of B-symptoms (n = 20), presence of mass felt per abdomen (n = 5), abdominal discomfort (n = 20) along with deranged platelet parameters. Mean maximum size of spleen was 21 cm.

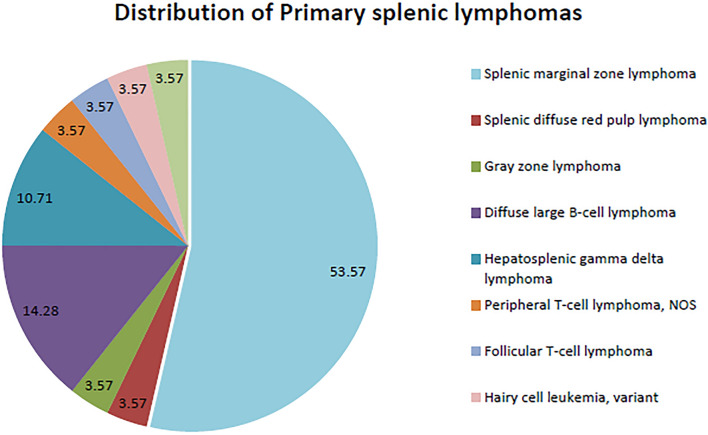

Various lymphomas were identified involving the red and the white pulp of spleen. Primary splenic lymphomas (n = 28, 84.84%) comprised majorly of splenic marginal zone lymphomas (SMZL) (n = 15, 45.45%) (Fig. 3A–G) followed by hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (n = 3, 9.09%) (Fig. 4A–L), Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, Not otherwise specified (n = 1, 3.03%) Fig. 4E–H, Follicular T-cell lymphoma (n = 1, 3.03%), splenic B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable (n = 2, 6.06%), diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (n = 4, 12.12%) Fig. 3 K, L and splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma (n = 1, 3.03%) (Fig. 3 M, N). One of the cases of SMZL transformed to DLBCL over the therapeutic course. With the help of peripheral smear, flowcytometry and bone marrow aspiration, one of the cases of splenic B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable was reclassified as hairy cell leukemia, variant. The diagnosis of splenic lymphomas was confirmed using the defined criteria in prior literature (Figs. 2, 3, 4, Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Microphotograph of normal spleen showing white pulp and red pulp. [H&E Ax16]. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: Microphotograph showing Expanded white pulp with prominent marginal zone. [B × 40, C × 100] There is coalescence of follicles(Red arrow) [C × 100]. Red pulp shows small lymphoid nodules [D × 100].The cells are immunopositive for CD20 [E], BCl2 [F], negative for CD23 [G]. Mantle cell lymphoma: Sheets of atypical lymphoid cells [H × 100] positive for CD20 [I] and Cyclin D1 [J]. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma: Needle core biopsy from spleen shows large atypical lymphoid cell involving red pulp. [K × 100]. The cells are immunopositive for CD20 [L]. Splenic diffuse red pulp lymphoma: Section shows marked expansion of the red pulp with infiltration by small size lymphoid cells. Small atretic white pulps are seen. [M × 16, N × 100]. The cells are immunopositive for CD20 [N]

Fig. 4.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: Microphotograph shows needle core biopsy from Spleen with infiltration of red pulp by large atypical lymphoid cells with moderate amount of cytoplasm. [Ax40, Bx200]The cells are immunopositive for CD30 [C] and ALK [D]. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, NOS: Section shows diffuse infiltration of red pulp by small to intermediate size atypical lymphoid cells which are immunopositive for CD3 [F], CD5 [G] with partial loss of CD7 [H]. Hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma: Microphotograph showing red pulp involvement by atypical large cells [I × 200]. Involvement of liver with sinusoidal infiltration by atypical lymphoid cells [J, × 200]. Atypical lymphoid cells immunopositive for CD3[K × 200] and CD56 [L × 200]

Fig. 2.

Distribution of Primary splenic lymphomas in our study; Splenic marginal zone lymphomas formed the majority of the study group

Table 2.

Demographics and clinical presentation of Primary splenic lymphomas:

| Age/sex | Presenting complaints | Primary diagnosis | Management | Patient status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 62/M | Splenomegaly and B-symptoms | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 2 | 37/M | Splenomegaly with hilar lymphadenopathy and B-symptoms | SMZL | CVP followed by Splenectomy | Alive |

| 3 | 14/M | B symptoms with splenomegaly | PTCL, NOS | Splenectomy + Chemo | Died |

| 4 | 64/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 5 | 54/F | Splenomegaly with B-symptoms | SDRPL | Splenectomy Had leukemic phase | Died |

| 6 | 58/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 7 | 52/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | ||

| 8 | 48/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | ||

| 9 | 50/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 10 | 52/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 11 | 59/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | |

| 12 | 54/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 13 | 65/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | ||

| 14 | 54/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 15 | 51/M | Splenomegaly | Follicular T–cell Lymphoma | Splenectomy + Chemo | Alive |

| 16 | 19/F | Splenomegaly with menorrhagia | HSTCL | VCR | Alive |

| 17 | 25/M | Splenomegaly | DLBCL | Lost to follow up | |

| 18 | 59/F | Splenomegaly | DLBCL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 19 | 56/M | Splenomegaly | DLBCL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 20 | 27/M | Splenomegaly | DLBCL | Alive | |

| 21 | 22/F | Splenomegaly | HSTCL | Alive | |

| 22 | 41/M | Splenomegaly with hepatomegaly | HSTCL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 23 | 66/M | Splenomegaly | Gray zone lymphoma | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 24 | 7/F | Splenomegaly | Splenic B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 25 | 46/M | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 26 | 50/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Alive | |

| 27 | 50/F | Splenomegaly | SMZL | Splenectomy | Alive |

| 28 | 63/F | Splenomegaly | Hairy cell leukemia, variant | Splenectomy | Alive |

**Few patients were lost to follow up

PTCL Peripheral T cell Lymphoma, SMZL Splenic Marginal Zone lymphoma, SDPRL Splenic Diffuse red pulp Lymphoma, DLBCL Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement was noted in the case of splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma, both cases of splenic B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable; and hepatosplenic gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma (HSTCL). The splenic diffuse red pulp lymphoma and splenic lymphoma unclassifiable was diagnosed as marginal zone lymphoma by flowcytometry of peripheral blood while HSTCL was diagnosed by bone marrow aspirate.

Other lymphomas involving spleen secondarily were gastric diffuse Large B-cell lymphoma (n = 2, 6.06%), mantle cell lymphoma (n = 1, 3.03%) (Fig. 3H–J), Hodgkin lymphoma (n = 1, 3.03%) and Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (n = 1, 3.03%) Fig. 4A–D.

Splenectomy was the main course of treatment for SMZL with a good overall outcome. Chemotherapy ± radiotherapy formed the mainstay in the other lymphomas including the DLBCL, with an overall benefit to the patient. The benign causes of splenectomies included idiopathic thrombocytopenia, extrahepatic portal vein obstruction and others.

Discussion

PSL have been a rarity, various authors over the years have defined their existence using different criteria in a quest to study their clinical, biological and pathological behavior. Dasgupta et al. defined the initial criteria for PSL which included presence of splenomegaly with absence of involvement of any extra-splenic sites like other nodes especially mesenteric or paraaortic nodes(excluding hilar nodes) or liver and a minimum of 6 month tumor free interval post splenectomy [5]. With a study of 11 cases, Skarin et al. included the splenic lymphomas with predominant feature of splenomegaly as primary splenic lymphomas [6].To account for a more advanced stage of the disease, Kehoe et al. included NHL arising in the spleen or primarily confined to the spleen as PSL, which also included the higher groups of Ahmann classification in their study of 21 cases [7, 8]. Ahmann et al. divided the PSL into three groups: I-with lymphoma confined to spleen, II-with involvement of hilar nodes, III- extrasplenic involvement including hepatic and marrow involvement with the higher group fairing worse than the group I or II. Dachman et al. concluded that PSL should have primary splenic involvement both radiologically which may be in the form of hypodense lesions on CT scan and on laparotomy and extrasplenic spread should occur with direct extension through the capsule to a contiguous organ [9]. In a study of 49 cases by Kraemer et al., the majority of their cases had splenomegaly, cytopenia and absence of any lymphadenopathy [10]. Our study considered the major defining factors for PSL. Splenic involvement is common in NHL; however, the criteria refine our diagnosis of primary splenic lymphomas or the lymphomas predominantly involving spleen without peripheral lymphadenopathy. Though none of the studies accounted for pancytopenia as a major diagnostic criterion, their common occurrence in PSL is still to be pondered upon. Radiologically, splenic involvement on CT scan can manifest as hypo or iso-attenuation; however may be completely normal; hence pressing need for PET scans in high degree of suspicion [11].Contrast enhanced CTs are of a great help for PSL.

The pattern of involvement in spleen can be manifested in the gross appearance. Beefy red appearance may constitute the predominant red pulp involvement with a differential of fibro congestive spleen. White pulp involvement may manifest as fleshy nodules which may be solitary or clustered and can mimic military tuberculosis. Ahmann classification for gross pathology can also be used [8].

SMZLs constituted the majority of the PSL of our study and other studies as well [12]. It is an indolent B-cell lymphoma, occurring most commonly in the elderly. Arising from the memory B-cells in the marginal zone, the splenic form is the most common of the marginal zone lymphomas. Historically, postulated origin from memory B-cell of marginal zone has been questioned in the recent studies emphasizing the molecular heterogeneity of the neoplasm [13]. Association with Hepatitis C virus infection along with regression following antiviral therapy has also been noted [14]. A higher prevalence of SMZLs is noted among people living in malaria endemic regions and people with autoimmune diseases, which may further lead to pancytopenia [15, 16]. The neoplasm has a biphasic cytology- expanded pale marginal zone (larger and paler) with a central zone of small lymphocytes (smaller and darker) and often difficult to ascertain. Micronodular aggregates with intra-sinusoidal clusters inside the red pulp can also be observed. Involvement of peripheral blood can show varied morphology- villous lymphocytes with polar villi, centrocytic like cells or lymphoplasmacytic cells. The neoplastic cells express mature B-cell markers like CD19, CD20 along with IgM, BCL2, MNDA and FMC7. Variable IgD expression is noted. The tumor cells are immunonegative for CD5, CD10, BCL6, CD23, cyclinD1, IRTA, CD25, CD103 and annexinA1 (Fig. 3B–G). Aberrant expression of CD5 or CD23 can be observed in some cases. In contrast to Nodal marginal zone lymphoma, PSL are CD43 negative. Aggressive variant shows a higher proportion of large cells. Transformation to large cell lymphomas may occur, though more commonly in the secondarily involved nodal sites [16]. Loss of 7q31-32 is the commonest genetic change. Genes involved in marginal zone differentiation like NOTCH2 (activating) and KLF2 (inactivating) have been identified. Microarray studies have established the potential markers including ILF1, CD40 and senataxin [17]. Though splenectomies are commonly practiced, chemotherapy with rituximab has emerged as an alternative [2]. SMZL, nodal MZL and Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia may represent a continuous spectrum with the similar immunophenotype and hence need further studies for the hypothesis [12]. Caution should be taken to avoid over diagnosis of splenic marginal zone hyperplasia, a benign entity. Expansion of polyclonal lymphocytes and lack of characteristic cytogenetics abnormalities with minimal splenic enlargement, white pulp involvement and absence of clusters in the sinusoids helps the diagnosis.

Often considered the most common PSL by various authors, the incidence of DLBCL has varied between 22.4 and 77% among various studies and often has a poor outcome [18]. Grosskreutz et al. reported 8 cases of diffuse large cell lymphoma in their case series of 10 PSL. Approximately 40% of systemic DLBCL also show splenic involvement. Primary splenic DLBCL are noted to have an association with HIV and Hepatitis C virus, which may point toward a possible role of HCV in the pathogenesis [19, 20]. DLBCL can either involve the white pulp in macronodular or the micronodular form or the red pulp (least common) with the red pulp involvement and micronodular form associated with a poorer prognosis [19]. Diffuse infiltration of white pulp with large nodular aggregates of large cells is a common finding however monomorphism can also be observed. [12] Micronodular form may also show morphological features of T-cell/ histiocyte rich large B-cell lymphoma [21]. Red pulp can be involved along the splenic cords and sinuses with monomorphic tumor cells and requires differentiation from indolent lymphomas (Fig. 3K). Though there is no difference in the immunophenotype in comparison to the nodal DLBCL, Bcl6 immunopositivity is common in splenic DLBCL. Transformation from low-grade lymphomas to DLBCL should be ruled out with the morphological and immunophenotypic characteristics. In comparison to systemic DLBCL, splenic DLBCL tend to have a longer progression free survival [19]. DLBCL was the second most common PSL in our study concordant with another Indian study that reported 30% of cases as DLBCL showing predominant splenic involvement. [12].

Secondary splenic involvement by CLL/SLL is common and may suggest the homing tendency of the lymphoid cells to spleen due to higher expression of adhesion molecules like CD44 and CD11c [22]. Hermann et al. studied 52 cases of diagnostic splenectomies, of which 16 (31%) showed evidence of lymphoma predominated by lymphocytic lymphoma [23]. There is major involvement of white pulp along with red pulp. Trabecular, subendothelial infiltration and sinus involvement can be observed [24]. Mantle cell lymphoma involvement is similar to CLL, usually secondary and predominantly in the white pulp. Both primary and disseminated follicular lymphomas in the spleen have been described, with dominance of the latter. With predominant nodular involvement of white pulp, infiltration of spleen may occur, distorting the architecture by follicular pattern or with an overall preserved architecture (Fig. 3I, J). Immunophenotype of SLL, MCL and FL are same as nodal counterpart.

Primary splenic T- and NK-cell lymphomas are rare; however, have been reported in literature. Most commonly, diffuse red pulp involvement is noted [25] PTCL can involve the periarteriolar sheath, white or the red pulp. The tumor comprises an intermediate sized lymphoid population in an inflammatory milieu. Loss of pan T-cell markers with immunopositivity for CD3 can be observed. Hemophagocytosis can be observed. Clonal rearrangement of T-cell receptors supports the diagnosis. Presence of hallmark cells immunopositive for CD30 points toward ALCL.

SDPRLs (categorized under splenic B-cell lymphoma/ leukemia, unclassifiable) are rare manifested by splenomegaly, villous lymphocytes in peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement [26]. However, their differentiation from HCL, HCL-v and SMZL is of utmost importance. Diffuse involvement of red pulp, both cords and sinuses by monotonous lymphoid cells along with interstitial or intra-sinusoidal marrow involvement is characteristic (Fig. 3 M, N). The lymphoid cells are small to intermediate sized with scant cytoplasm, round nucleus and condensed chromatin. The villi are polar and cells show inconspicuous nucleoli. With a B-cell immunophenotype, the lymphoid cells are immunopositive for DBA 44 and IgG. The lack of characteristic involvement of white pulp as in SMZL and absence of markers for hairy cell like annexin A1, CD103 may aid the diagnosis. They typically lack expression of CD5, CD23, cyclinD1 and CD10. Absence of polymorphous population inclusive of plasma cells confirmed by CD138 immunonegativity rules out lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, which may be a differential in case of plasmacytoid morphology [27]. High expression of cyclin D3 which may be the result of CCND3 somatic mutations can be seen [28]. Chromosomal structural abnormalities like deletion 7q, trisomy 18 and deletion 17p can be observed. Mutations in NOTCH1, TP53 and MAP2K1 are associated with an aggressive outcome [29].

Hairy cell leukemia, a mature B-cell neoplasm involves the red pulp commonly, with atrophied white pulp and is characterized by the villous lymphocytes having circumferential villi. Absolute monocytopenia is an associated occurrence. The lymphoid cells infiltrate the splenic cords and may lead to formation of red blood cell lakes along with damage to splenic endothelial cells [30]. The cells may contain a reniform nucleus, inconspicuous nucleolus along with abundant clear cytoplasm. Bone marrow aspirate usually yields a dry tap due to the disease involvement. The cells are TRAP positive and show immunopositivity for CD19, CD20 (bright), FMC7, CD103, CD11c, CD25, CD123, DBA44, annexin A1 and BRAFV600E antibody. Cyclin D1 expression, though weak, can be observed in 40% of the cases; however, lack t(11; 14).

The hairy cell leukemia, variant also known as the prolymphocytic variant of HCL (categorized under splenic B-cell lymphoma/ leukemia, unclassifiable) consists of neoplastic cells showing combined features of both hairy cells and prolymphocytes. With the presence of circumferential villous processes, they characteristically contain a prominent nucleolus [26]. The lymphoid cells are TRAP negative and show immunopositivity for DBA44 and CD103. They are typically immunonegative for annexinA1, CD25, CD123 and BRAFV600E. MAP2K1 mutation along with deletion 17p can be observed in a third of cases.

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas (Waldenstrom’s macrogobulinemia) show bone marrow involvement along with presence of plasmacytic differentiation. Associated IgM paraproteinemia establishes the diagnosis of Waldenstrom’s macrogobulinemia. Diffuse red pulp involvement with plasmacytic morphology is characteristic. Immunopositivity for CD25 and CD22 (weak) combined with faint CD11c expression can be seen [31]. MYD88 L265P, a somatic mutation observed in > 90% of the cases determined by molecular or immunophenotypic methods can clinch the diagnosis along with immunonegativity for CD10, CD5, CD23. IgM and surface and cytoplasmic light chain expression is present. Deletion 6q is also seen.

Derived from the splenic gamma delta T-cells, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas are a distinctive group of T-cell lymphomas stereotypically involving the red pulp of the spleen and the marrow. These may arise in denovo; however, show a strong association with presence of conditions with immune dysregulation [32]. Sinusoidal pattern of involvement should raise the suspicion for this entity. The lymphoid cells can be small to large sized and display fine chromatin akin to blasts. Erythrophagocytosis can frequently be seen. The lymphoid cells are immunopositive for CD3, CD2, CD7, TIA1 and CD56. They show immunonegativity for CD4, CD8, CD57, granzyme, perforin and EBV (Fig. 4I–L). Majority of these are derived from gamma delta TCR lymphocytes. Structural chromosomal alterations like isochromosome 7q, trisomy 8 and loss of Y chromosome can be seen. STAT5B/ STAT3 mutations can be present causing dysregulation of JAK/STAT pathway.

T-large granular lymphocyte leukemia often shows involvement like HSTCL; however, the cells show ropey or condensed chromatin. They show immunopositivity for CD3, CD2, CD8, CD57, CD16, TIA1, granzyme and alpha beta TCR. Immunonegativity is seen for CD4, EBV and TCR gamma delta. CD5 and CD7 expression is variable. T-PLL can also involve the red pulp with destruction of white pulp and lack the cytotoxic granule markers [33].

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma and aggressive NK-cell leukemia have been reported with predominant splenic involvement. These show casual association with EBV and are immunopositive for CD56 and CD16 with absent sCD3 [34]

Hodgkin lymphomas can involve the spleen, and thus splenectomies were performed in early years for staging. The weight and size of the organ; however, does not correlate with degree of involvement. The periarteriolar and Malpighian corpuscle periphery are first to be involved, followed by diffuse involvement of the spleen [35]. Presence of granulomas should be examined with caution, ruling out all the benign, infectious and other malignant causes. In a study by Farrer et al., the histomorphology of splenic involvement matched to nodal involvement in 45% of the cases with 27% showing a fibrotic lymphocyte depleted morphology and the rest showing a lymphocyte predominant morphology irrespective of the primary nodal disease process [35].

Patterns of bone marrow involvement can also be useful in diagnosis of splenomegalies lymphomas [2]. Splenic lymphomas can lead to complications like gastrosplenic fistula, gastric ulcers and hematemesis [3]. Hence, splenectomies which tend to reduce the tumor burden and thereby make the remaining tumor amenable to chemotherapy may produce a better outcome [35]. They also help in overcoming the pancytopenia and can prolong remission.

Conclusion

Primary splenic lymphomas are rare and cause various complications. Appropriate management is guided by the precise and detailed evaluation by the pathologist. We have proposed two algorithms for the evaluation of splenic lymphomas with predominant white (Fig. 5) and red pulp involvement (Fig. 6). Though splenic biopsies are seldom done; their importance for the primary diagnosis is many times essential. A multiparameter approach aids the better patient management and disease-free survival. Not all cases with splenic involvement undergo biopsy or excision and hence their prevalence may be underestimated like hairy cell leukemia whose diagnosis does not require splenic evaluation. However, knowing the rarity of PSL; the study realizes the importance of detailed clinicopathological evaluation.

Fig. 5.

Approach to lymphomas involving spleen with predominant white pulp involvement

Fig. 6.

Approach to lymphomas involving spleen with predominant red pulp involvement

Author Contributions

Concept: SM, Data Collection: SJ, PR, TM. Manuscript writing: SJ, PR Clinical Information: AG, MA, MM, RP, SB. AS. Manuscript review: SM, JD, MCS. Final Review–SM.

Funding

The data was collected as part of projects- SERB ECR/2015/415, SERB EEQ/2016/402.

Data Availability

Most of the raw data submitted as tables. For any further clarification the data will be available. The data was presented in SOHO Italy 2020. The abstract published Jain, S., Mallick, S., Ramteke, P., Gogia, A., Agarwal, M., Dass, J., Yadav, R., & Sharma, M. (2020). Pandora box of Lymphomas in Spleen: Session: Non Hodgkin and Hodgkin Lymphomas. Hematology Reports, 12(s1).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest amongst the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gobbi PG, Grignani GE, Pozzetti U, et al. Primary splenic lymphoma: does it exist? Haematologica. 1994;79(3):286–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iannitto E, Tripodo C. How I diagnose and treat splenic lymphomas. Blood. 2011;117(9):2585–2595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-271437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingle SB, Hinge Ingle CR. Primary splenic lymphoma: Current diagnostic trends. World J Clin Cases. 2016;4(12):385–389. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i12.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dasgupta T, Coombes B, Brasfield RD. Primary malignant neoplasms of the spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:947–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain S, Lone MR, Goswami A, et al. Lymphoma subtypes in India: a tertiary care center review. Clin Exp Med. 2021;21(2):315–321. doi: 10.1007/s10238-021-00683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skarin AT, Davey FR, Moloney WC. Lymphosarcoma of the spleen. Results of diagnostic splenectomy in 11 patients. Arch Intern Med. 1971;127(2):259–265. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1971.00310140087011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehoe J, Straus DJ (1988) Primary lymphoma of the spleen. Clinical features and outcome after splenectomy. Cancer. 62(7): 1433–1438. 10.1002/1097-0142(19881001)62:7<1433::aid-cncr2820620731>3.0.co;2-v [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ahmann DL, Kiely JM, Harrison EG, Payne WS (1966) Malignant lymphoma of the spleen. A review of 49 cases in which the diagnosis was made at splenectomy. Cancer. 19(4): 461–469. 10.1002/1097-0142(196604)19:4<461::aid-cncr2820190402>3.0.co;2-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Dachman AH, Buck JL, Krishnan J, Aguilera NS, Buetow PC. Primary non-Hodgkin’s splenic lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 1998;53(2):137–142. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(98)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraemer BB, Osborne BM, Butler JJ (1984). Primary splenic presentation of malignant lymphoma and related disorders. A study of 49 cases. Cancer. 54(8): 1606–1619. 10.1002/1097-0142(19841015)54:8<1606::aid-cncr2820540823>3.0.co;2-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Li M, Zhang L, Wu N, Huang W, Lv N. Imaging findings of primary splenic lymphoma: a review of 17 cases in which diagnosis was made at splenectomy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gujral S, Lad P, Subramanian P, et al. Histopathological audit of splenectomies received at a cancer hospital. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54(3):487. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.85080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadaki T, Stamatopoulos K, Belessi C, et al. Splenic marginal-zone lymphoma: one or more entities? A histologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(3):438–446. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213419.08009.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merli M, Carli G, Arcaini L, Visco C. Antiviral therapy of hepatitis C as curative treatment of indolent B-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(38):8447. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i38.8447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos TSD, Tavares RS, de Farias DLC. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: a literature review of diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Rev Bras Hematol E Hemoter. 2017;39(2):146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2016.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruiz-Ballesteros E, Mollejo M, Rodriguez A, et al. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: proposal of new diagnostic and prognostic markers identified after tissue and cDNA microarray analysis. Blood. 2005;106(5):1831–1838. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimono J, Miyoshi H, Kiyasu J, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of primary splenic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(5):719–727. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosskreutz C, Troy K, Cuttner J. Primary splenic lymphoma: report of 10 cases using the REAL classification. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(5–6):749–753. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120002492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeshita M, Sakai H, Okamura S, et al. Splenic large B-cell lymphoma in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(8):878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Mann KP, Holden JT. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma presenting in the spleen: a clinicopathologic analysis of 3 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2004;12(1):31–37. doi: 10.1177/106689690401200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bairey O, Zimra Y, Rabizadeh E, Shaklai M. Expression of adhesion molecules on leukemic B cells from chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients with predominantly splenic manifestations. Isr Med Assoc J IMAJ. 2004;6(3):147–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermann RE, De Haven KE, Hawk WA. Splenectomy for the diagnosis fo splenomegaly. Ann Surg. 1968;168(5):896–900. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196811000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kansal R, Ross CW, Singleton TP, Finn WG, Schnitzer B. Histopathologic features of splenic small B-cell lymphomas. A study of 42 cases with a definitive diagnosis by the World Health Organization classification. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;20(3):335–347. doi: 10.1309/HWG0-84N3-F3LR-J8XB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan JKC. Splenic involvement by peripheral T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2003;20(2):105–120. doi: 10.1016/S0740-2570(03)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vig T, Kodiatte TA, Manipadam MT, Aboobacker FN. A rare case of splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma (SDRPL): a review of the literature on primary splenic lymphoma with hairy cells. Blood Res. 2018;53(1):74–78. doi: 10.5045/br.2018.53.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanellis G, Mollejo M, Montes-Moreno S, et al. Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma: revision of a series of cases reveals characteristic clinico-pathological features. Haematologica. 2010;95(7):1122–1129. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curiel-Olmo S, Mondéjar R, Almaraz C, et al. Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma displays increased expression of cyclin D3 and recurrent CCND3 mutations. Blood. 2017;129(8):1042–1045. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-751024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martinez D, Navarro A, Martinez-Trillos A, et al. NOTCH1, TP53, and MAP2K1 mutations in splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma are associated with progressive disease. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(2):192–201. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pilon VA, Davey FR, Gordon GB, Jones DB (1982) Splenic alterations in hairy-cell leukemia: II an electron microscopic study. Cancer. 49(8): 1617–1623. 10.1002/1097-0142(19820415)49:8<1617::aid-cncr2820490815>3.0.co;2-c [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Ocio EM, Hernández JM, Mateo G, et al. Immunophenotypic and Cytogenetic Comparison of Waldenström’s Macroglobulinemia with Splenic Marginal Zone Lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2005;5(4):241–245. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2005.n.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pro B, Allen P, Behdad A. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma: a rare but challenging entity. Blood. 2020;136(18):2018–2026. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osuji N, Matutes E, Catovsky D, Lampert I, Wotherspoon A. Histopathology of the spleen in T-cell large granular lymphocyte leukemia and t-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: a comparative review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(7):935–941. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000160732.43909.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao Q, Huang Y, Ye Z, Liu N, Li S, Peng T. Primary spleen extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type, with bone marrow involvement and CD30 positive expression: a case report and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:169. doi: 10.1186/s13000-014-0169-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farrer-Brown G, Bennett MH, Harrison CV, Millett Y, Jelliffe AM. The diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease in surgically excised spleens. J Clin Pathol. 1972;25(4):294–300. doi: 10.1136/jcp.25.4.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bairey O, Shvidel L, Perry C, et al. Characteristics of primary splenic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and role of splenectomy in improving survival: primary Splenic DLBCL. Cancer. 2015;121(17):2909–2916. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the raw data submitted as tables. For any further clarification the data will be available. The data was presented in SOHO Italy 2020. The abstract published Jain, S., Mallick, S., Ramteke, P., Gogia, A., Agarwal, M., Dass, J., Yadav, R., & Sharma, M. (2020). Pandora box of Lymphomas in Spleen: Session: Non Hodgkin and Hodgkin Lymphomas. Hematology Reports, 12(s1).