Abstract

The present study aimed to know and analyze the repercussions and legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic for the Unified Health System from the perspective of health managers working in Manaus, a city considered the epicenter of the pandemic in Brazil. This qualitative research was designed as the study of a single incorporated case and conducted with 23 Health Care Network managers. The analysis was applied in two thematic coding cycles (values and focused coding methods), with the aid of the ATLAS.ti software. The categories we analyzed covered the lessons learned within the scope of the work process, change in stance, and human values, as well as the coping strategies adopted by individual or team initiatives or by the incorporation of innovations in practices. This study highlighted the importance of strengthening primary health care; of promoting team spirit in the service and establishing partnerships with public and private institutions, of being integrated with the training in complex situations, and of reflecting on human values and appreciation of life. Coping with the pandemic promoted an in-depth reflection about the functioning of the Unified Health System and the individual ways of being.

Keywords: community and public health, emergency care, administration

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic became a global crisis impacting on public health, marked by high dissemination of the virus and by alarming death rates, which will certainly have profound and long-lasting repercussions on society. It is not known how long the crisis will last, presenting both a challenge and a collective desire to overcome the pandemic.

The problems faced in the pandemic are aggravated by the rapid spread of the virus, unpredictable behaviors, and unique characteristics, resulting from a myriad of complex interactions between the pathogen and societies and causing catastrophic harm to health, society, and economy (Slater et al., 2022). It is a fact that pandemics transform collective behaviors in inexplicable and unexpected ways and cause various reactions, such as horror and fear, since people do not know how to deal with the situation (Schwarcz & Starling, 2020).

Many countries experienced a massive public health emergency, with a total collapse of health systems; conversely, other countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea managed to delay spread of the disease by implementing successful preventive strategies, based on science and the experience of other countries (The Lancet, 2020).

In the Brazilian state of Amazonas, the pandemic progressed rapidly and presented two catastrophic disease peaks (March 2020 and January 2021), with a high number of deaths occurring in the capital city, Manaus, which became the disease epicenter in the country during these periods, and Manaus was the place where a new virus strain (P.1) was discovered (Sabino et al., 2021). On 2 June 2022, Manaus recorded 290,919 confirmed cases and 9703 deaths due to COVID-19 while in a stabilization process as a result of vaccination progress (Amazon Health Surveillance Foundation, 2021).

Dramatic scenes characterized the health system in Manaus, having international repercussions and requiring real-time adjustments in health services and timely decision-making by managers at all levels. Undoubtedly, the experience resulted in important reflections and analyses related to the health system and even personal values. Looking at past experiences is a valuable strategy to formulate answers, content, standards, and collective lessons about the pandemic (Schwarcz & Starling, 2020).

Promoting effective responses to outbreaks and infectious diseases is a significant challenge in global societies; however, learning at the level of systems with the current response to the COVID-19 outbreak is fundamental to respond to secondary waves or future new viral outbreaks (Slater et al., 2022).

Coping with this pandemic showed to be full of uncertainties and errors but certainly allowed for significant learning and legacy for public health, which raises the following question: Which is the legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic for the health system in Manaus?

The Brazilian public health care system is called Unified Health System (UHS) or by its acronym in Portuguese—SUS (Sistema Unico de Saúde). The present study aimed to know and analyze the repercussions and legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic for the SUS, from the perspective of health managers working in Manaus. It is expected that the production of knowledge based on experiences and actions that had an impact on management of the pandemic may provide new insights and ways of adapting, in order to promote resilience and practices necessary for new coping mechanisms.

Data analysis and discussion are anchored in the legal bases and in the organizational principles of the SUS: universal access to health services, equity (reduction of inequalities), integrality (comprehensive and resolute care), regionalization (organization of services according to the needs of the territory), hierarchization (organization of services by levels of complexity), decentralization (redistribution of power and responsibility between the spheres of the government), single command (spheres of the government’s autonomy and sovereignty in their decisions and activities), and popular participation (participation of the society in the construction and management of the SUS) (Law No. 8080, 1990) (Decree No. 7508, 2011). In addition, it accepts the centrality of the worker in the production of care that, in critical scenarios, operates using new elements and processes of capacity reconstruction. From this, we can derive the methodological direction of valuing the narrative as a way of accessing the experience of coping and reinvention, in the face of the unforeseen events and the negotiation of priorities and commitments in real work, which also finds inspiration from the approach of ergology (Ramos et al., 2020).

Method

Type of Study

This was qualitative research designed as the study of a single incorporated case (Yin, 2014), but due to its delimitation to a complex phenomenon (facing the pandemic), in a specific context (municipality), it required the incorporation of different analysis units (different types of services and management levels) and sources of evidence (interviews with different informants and documents).

Research Scenario

The study was conducted in Manaus, the capital city of Amazonas, with 2,219,580 inhabitants, which comprises 52.75% of the state’s population, 13.01% of the northern region, and 1.04% of Brazil, being the seventh most populous capital (DATASUS, 2020).

The Amazonas State Health Secretariat is responsible for the formulation and development of policies aimed at the organization of the SUS in Amazonas, managing secondary and tertiary levels of health in Manaus, with 58 health care institutions (HCIs) (Amazonas, 2020a). Primary health care (PHC) management, under the coordination of the Municipal Health Secretariat Manaus, manages 305 HCIs, which covers 67.28% of primary health care (Amazonas, 2020a).

To fight against COVID-19, the Health Care Network (HCN) was reorganized, having the following priority entry points: Basic Health Units (BHUs), Emergency Care Services (ECSs), Emergency Care Units (ECUs), and First Aid (FA) (Amazonas, 2020b). Clinical or intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization occurs by medical regulation, via the Regulated Emergency Transfer System and transportation by the Mobile Emergency Care Service (Manaus, 2020).

Data Collection Procedures and Instruments

The interviews took place from June 22 to November 10, 2020, and were carried out by the first (master’s degree), second (master’s degree), and fourth (PhD) authors and nurses with previous experience in collecting and analyzing qualitative data, with no interpersonal relationship with the participants. A semi-structured script developed and applied in a simulation by a team of six researchers was used, in addition to being evaluated after the first three interviews, with no need for adjustments in the questions. It included 11 questions aimed at gathering the characteristics of the participants and 8 guiding questions focused on the repercussions and legacy of the pandemic, such as: How do you assess the process of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and how does your work bring interaction with others? How do you think the teams experience and adapt to the new prescriptions/guidelines and arrangements at work? Do you notice any individual and team strategy that are being devised? Which ones?

The study included 23 managers of municipal and state public services who worked in the fight against COVID-19 and verbally expressed interest in participating in the research. They were selected for convenience, meeting the criteria of being active in the position for at least 30 consecutive days, the minimum period during which it is possible to gain sufficient experience in the service, considering the instability generated by several manager turnovers during the period, in addition to representativeness of the strategic (first and second levels) and operational (BHU, ECU/ECS, FA, and hospitals) levels.

Previous contacts were made to present the study and schedule the interviews, which were developed in a place suggested by the participants or by means of virtual meetings via the Google Meet application, recorded in digital audio or video, and lasting a mean of 40 minutes. After each interview, the relevant points and the researchers' perceptions were recorded. There was no refusal to participate by, or need for follow up with, potential participants.

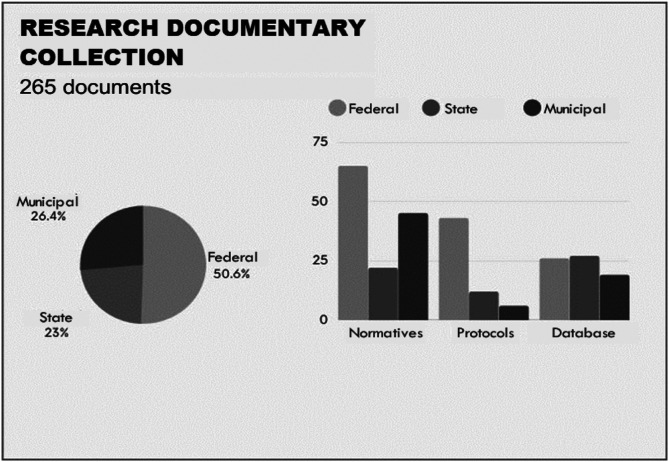

The documentary research was carried out until June 2021, covering free-access documents available in the institutional websites of national, state, or municipal scope, organized in a specific Google Drive and totaling 265 documents (Figure 1). They were systematized in normative protocol and information systems data through an Excel spreadsheet prepared by the authors, which contained indication of authorship, date, purpose/subject matter, and added to the analytical process for comparison and in-depth interpretation.

Figure 1.

Description of the research documentary collection.

Data Treatment and Analysis

The interviews were transcribed with the aid of the Google Docs tool, maintaining authenticity and literality. The transcribed texts were made available for knowledge and review by the interviewees, but there was no demand for another transcription. Qualitative data saturation was confirmed by the recurrence of the contents and scope of magnitude of the codes, allowing consistent interpretations.

In the analysis, two thematic coding cycles were applied, proposed by Johnny Saldaña with the aid of ATLAS.ti (version 8.0), the qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti, 2019): (1) the values method, which categorized the data corpus, aiming to explore cultural values, identity, experiences, and intra- and interpersonal actions of the participants in the case study; and (2) the focused coding method, which gathered the corpus by thematic similarities in order to deepen the discussion (Saldaña, 2013), resulting in two research categories, which were further subdivided into six subcategories, with a magnitude of 199 citations.

To increase consensus, a researcher was in charge of coding, which was reviewed by a second one, and submitted for consensus by three collaborating researchers at specific meetings.

Triangulation between data from the interviews and the documents took place to the extent that, in the categorization process, any references to norms or guiding policy formulations that impacted the processes of coping with the pandemic were identified, in order to better understand the basis of the decision-making used by the actors involved in the management process.

Ethical Aspects

The study met the National Health Council standards for research involving human beings (Resolution No. 466/12), and obtained consent from the Manaus health authorities and the participants and approval by the Committee of Ethics in Research with Human Beings (CAAE: 31844720.6.0000.5016). In order to preserve anonymity, the transcripts were identified by means of acronyms and numbers, according to the workplace and the number of managers interviewed.

Results

Among the study participants, there was a predominance of women (57%), aged 40–49 years (61%); specialists (65%); nurses (39%); and employees hired via public tender (65%). Of the study participants, 39% had 16–20 years of training, 26% had been part of the institution for a period of 1–3 years, and 57% had worked during the pandemic for a period of more than 6 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of the Research Participants.

| Social-professional characteristics | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 |

| Female | 57 |

| Age | |

| 30–39 years old | 22 |

| 40–49 years old | 61 |

| 50–59 years old | 13 |

| >60 years old | 4 |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 39 |

| Physician | 15 |

| Dentist | 4 |

| Physiotherapist | 8 |

| Administrator | 22 |

| Social worker | 4 |

| Biologist | 4 |

| Economist | 4 |

| Graduate studies | |

| Specialization | 65 |

| Master’s degree | 27 |

| PhD | 4 |

| None | 4 |

| Training time | |

| 7–9 years | 13 |

| 10–15 years | 17 |

| 16–20 years | 39 |

| >20 years | 31 |

| Workplace | |

| Administrative headquarters | 34 |

| Hospitals | 22 |

| ECS/ECU | 27 |

| BHU | 17 |

| Institutional contract | |

| Temporary | 35 |

| Statutory | 65 |

| Time working in the current institution | |

| 1–11 months | 13 |

| 1–3 years | 26 |

| 4–10 years | 22 |

| 11–15 years | 22 |

| 16–20 years | 17 |

| Time working in the fight against COVID-19 | |

| 3–4 months | 13 |

| 5–6 months | 30 |

| >6 months | 57 |

Source: Research data.

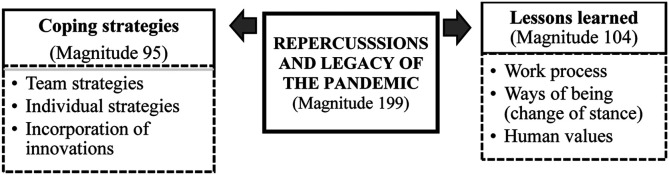

Two research categories were created, which were further divided into six subcategories (magnitudes indicating the number of citations or excerpts), encompassing the lessons learned within the scope of the work process, changes of stance, and human values to the coping strategies adopted, either by means of individual or team initiatives or by the incorporation of innovations in practices (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Magnitude by analysis categories.

Team Strategies

This category encompasses collective initiatives motivated by the difficulties experienced during the pandemic, addressing issues ranging from simple actions such as production of homemade masks to more complex ones such as active and collective participation in operation and organization of the health unit, strengthening of integration and teamwork, integration of the care-management sector with other sectors (Public Health School of Manaus/Residency Program in Family and Community Health), proactivity of professional categories (Nursing/Physiotherapy) and strategic sectors (Health Districts/Patient Safety Center/Hospital Infection Control Commission at local and state levels), and differentiated strategies to recruit and/or replace individuals.

[...] The Safety Center was present in the process, they guided many people. It came a time when we said: “Were going to change the Physiotherapy process,” for example, because we noticed that placing patients in the prone position while awake made a difference. But why? Through the root cause analysis we made of the death cases. H1G13

The Health Districts were extremely strong in facing this disease; despite all the difficulties and limitations, they were able to create a support network for the employees [...] aiming to provide all the necessary support and referrals. GM5G17

[...] Nursing is really human and, in the face of a problem, they get organized; they quarrel a lot but when there is a problem, they get organized and things happen.

Public Health management, the clinic management, it's thanks to Nursing not to the physicians! So, the Clinic management is defined by the Nursing professionals characteristics and training. [...] I did not notice any difficulty or problem adhering to the plan or performing a set of actions from the plan for coping. G4G22

In facing COVID-19, the category of respiratory physiotherapists was perhaps the most important one within the intensive care team, and the patients themselves have talked much about the need of these professionals in recovery from their health condition. Physiotherapy offered to help! But the respiratory specialty was essential within the intensive care team, mainly when speaking of the severe cases, because the nurses, not the physicians, were the ones who treated and provided humanized care to the moderate cases. G4G22

The issue of nurses more engaged within the team, not only with an assistant approach, but also as managers of the whole service, because all aspects of catering, laundry, even visits that could not be made, all this communication was conducted by the Nursing team! H5G23

Individual Strategies

Despite the reports of those who “hid” from the pandemic, the leading role of people stood out: those who sacrificed their vacations and other leave; motivated coworkers; and those who worked in an effective manner with other states in exchanging experiences or providing remote support in addition to collective mobilization to strengthen spirituality in the workplace and engagement in the development and organization of protocols, processes, guidelines, and training.

We have people that assumed this leadership role really well in each unit [...] easily identifiable [...] they were able to organize all that flow. GE1G2

We discovered people. There were some diamonds in the rough. Some people really surprised. It's not that they remained unnoticed but, despite the shyness of some of them, they brought really good ideas, the people's view [...], I think it was nice, we started to hear other professionals more. It's extremely important. GE3G21

Incorporation of Innovations

A number of innovations were evidenced, namely: (1) relational aspects (welcoming) involving the patient’s contact with the family members through virtual visits and virtual hospital reports on the patient’s health status, in addition to the creation of a golden code to indicate hospital discharge; (2) health care actions, such as offering a chat channel to the community and educational videos with instructions to the community and to professionals, 24/7 virtual monitoring of patients, drive-thru influenza vaccination, as well as psychological support and performance of COVID-19 tests specifically for health care professionals; (3) health management, involving more complex measures, such as integration with the Public Health School of Manaus through extension and graduate projects, with the incorporation of scholarship holders in the service in order to strengthen care; training of professionals through a partnership with the Médicins Sans Frontiêres (Doctors Without Borders) non-governmental organization and the National Public Security Force; communication with the university for incorporation of clinical research into the service (care and protocol), donation of materials, and production of personal protective equipment (PPE); implementing more operational strategies with the incorporation of physiotherapy in all hospital sectors, integration of the dentistry team in reception of the patients, and analysis of causes of death; implementation of employee’s outpatient services and the definition of 18 BHUs as a reference for the care of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases; and expansion of the opening hours of 32 BHUs (Monday to Friday from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.) and 1 BHU operating in the day shift (every day from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.).

We did not allow people accompanying patients to enter the hospital [...] the social worker organized the medical reports with care provision to the users and the timetables [...] each hospitalization sector had a time for the report [...] We said: “if it is not possible to move around the hospital, how can we do anything?” We bought a small sound box and camera, connected them with the computers in the outpatient clinic, and the physician up there in the ICU talked live with the family down there, accompanied by a social worker. This was how the medical reports were provided. In this way, the family was able to receive the medical report, talk with the attending physician, ask questions, but did not get exposed [...] All that was coordinated by the Social Service. H1G9

I highlight the partnerships with the universities, with the Public Health School of Manaus itself and with our scholarship program [...] It's important to have differentiated strategies [...] having participation of private initiatives and of the academic sphere. GM6G19

Lessons Learned: Work Process

The pandemic also brought up in-depth reflections about the work process and strategies to strengthen the SUS, revealing complex and structuring points. For example, (1) the need to have an integrated and organized HCN, with shared decision-making between state and municipal managers, should be addressed. (2) PHC should be strengthened and the accessibility to PHC should also be improved, based on health surveillance actions and community mobilization through Community Health Agents (CHAs). (3) The valuable contribution of technology in health care and information management and the relevance of incorporating management tools during the pandemic, such as communication, strategic planning, timely decision-making, and standardization, should be analyzed and integrated. (4) An approach between the SUS and class councils should be developed for a greater integration with the universities and partnerships with private companies, with the purpose of integrating new people into the service.

We could have worked more intensively in engaging the community, we could have searched for arrangements towards greater mobilization, with health promotion, with the community health agents' strength, and perhaps, let’s say a more intense monitoring of the plan itself, in a more systematic and methodological way. I think that it could be improved, thinking about tools and instruments that could be used more appropriately in possible future pandemics, giving greater visibility, with more clarity in the paths to be followed. Although we consider that the paths we’ve taken are assertive. GM4G15

I think that the integration between the municipal and state levels could have been better, as we have a shared network, neither the state or the municipality has single command. GM4G15

I see a major weakness, due to the whole scenario in the state, of frequent changes, inconsistency and instability, we were not able, I would say, to establish an articulation for a better integrated handling in the Municipality of Manaus, and this would make a big difference [...] It is something that remains there for the future, so that we can actually try the network, connecting and not dividing. We could have certainly grown and been more effective in our actions! GM4G15

What should be strengthened within SUS? Increasingly, the issue of the residencies in health, of the specializations and, at the same time, establishing public–private partnerships. Because the sector provides equipment, starts the services and we begin with the services motivated, engaged, and committed. Both permanent employees, who are the basis of the SUS, and the strengthening of residencies are necessary. Labor represents 70% of our budget. Health care is provided with physicians, nurses, and technicians, that is, people, who need to be motivated, committed, and prepared to face these challenges. This partnership between university, employees, and those who provide services and products is the way to improve health, to strengthen primary care. GM6G19

The benefit of team integration was evidenced, with shared and participative management as well as the importance of institutionalizing brief and practical normative instruments for communication in the services, aiming at the continuous evaluation of processes for continuous learning. It is worth highlighting how valuable it was to implement a differentiated risk classification for COVID-19 cases and the incorporated benefits in relation to the scheduling modalities, flows of care, and companions in the health services.

[They changed] our documents. Before we created a protocol for everything and we noticed that, if you want to have a faster view, a flowchart is necessary, something visual, playful, objective, clear, which allows you to say “take here and place here.” Over-elaborated things [No], if you have the basics, it’s more feasible than a very complex thing. That changed the management's view in the sense of how information should be transmitted [...] Another issue is over-bureaucratizing things - get the team together and show everything in situ. It’s no use writing documents! Of course they’re necessary at several moments, but if you make the correction immediately, together, and everyone understands and comes in to participate in the process, it really makes the difference! H1G13

One aspect that I think should be improved is the scheduling of appointments. It used to be in-person, people had to come to the Unit, “they gather a lot of people to schedule that appointment”. Now the outpatient service has an appointment system via a landline and cell phone, this is new for the users too, sometimes they are skeptical, because they usual thing is to come here and sign a document. That raises suspicions. H4G20

An in-depth reflection emerged about the need for decision-making to quickly solve the problem in the SUS scope, in order to rethink the process and confer administrative celerity.

Decision-making in pandemic times needs to be taken in real-time, we were having a very high number of deaths, so this real-time was very short then. G4G22

Lessons Learned: Ways of Being (Change of Stance)

There were also changes in the ways of being (change of stance), with regard to incorporation of continued PPE use in the service; opening windows for air circulation; strengthening of the hygiene measures in the Unit, inclusion of relaxation and stretching exercises at work; welcoming and collaborative behavior with coworkers and users (care with others); adoption of rigorous hygiene habits before making contact with the family; physicians working in urgencies regardless of their specialty; and even changes in collective behaviors such as the community seeking for emergency health care in BHUs.

I see that people took all that was said to us very seriously and, until now, most of them have not abandoned PPE use, distancing, [...] qualified listening [....] I notice that this has been intensified in the team... and this will not end or be lost so fast! Until now we have been using the whole work process that was implemented at the beginning of the pandemic. UBS2G8

We experienced a process of war, we saw an orthopedist surgeon working as a clinician, from the civil point of view it is unthinkable! As we were there, with a team spirit, to help people to face, it was done… It was something unprecedented in my 22 years as a professional! Willing to make that movement, but concerned on the other hand, “I’m an orthopedist surgeon, how am I going to intubate someone?” But it was done in times of war and I had another intensivist doctor beside me… “You’re right, keep going!” Then I helped! H3G12

Lessons Learned: Human Values

The pandemic mobilized feelings, reflections, and personal perspectives, revealing changes in the view about ways of living and in human relationships, either in the family or between team members; it aroused humanity, union, and collective solidarity; it allowed health care professionals to experience or put themselves in the place of the patients; it redefined the real value of life.

[...] it changed our perception of things in general, it' changed the way we see life, the way we work, the way we work with the team, with coworkers, and with patients. I think that it changed us inside[...] UBS1G6

I learned, grew and evolved as a health professional, person, boss, work colleague, and that is going to be stamped in my history. We used this situation to notice and assess many important things in our life that we sometimes did automatically, in our busy life we fail to notice some things that are very important for us. God, family, friends, the importance of work, the love that I put in what I do, things that changed and that changed me. I think that it is going to grow, evolving spiritually as a result of this process. UBS1G6

I believe that, when in a situation of extreme difficulty, human beings living here in this world tend to join forces, to think together, to create instruments that may make it possible to continue surviving. I think that these moments imposed by the pandemic inspired many reflections on us as humans. I think that the most important, for me, is related to synergy, to joining intelligences, joining work efforts, the willingness to make it right [...] H3G12

It is being quite a life experience. I think that we will become better people, anyone who cannot look back and see what they can do for the others is in the wrong place. GE3G21

[...] as many team members eventually got sick, they also found the same needs that the patients were experiencing at that time, so they were able to see themselves as patients and their stance changed gradually. It was verified that there was a need for a conversation, because the patients remained a lot time alone, without their families, and the health care professionals themselves did not enter the sector to talk to the patients, so they started to develop depression. And the employees started talking and learning the story of each of the patients there. H5G23

Discussion

The pandemic had significant effects on people in the personal, social, emotional, psychological, economic, and professional spheres. The reports revealed the various ways to adapt and reorganize personal and professional life. Surviving in a practical environment signaled by uncertainty requires adaptive mindsets, resilience attitudes, acceptance of vulnerabilities, and a dynamic base. There is an urgent need for innovation, for thinking outside the box, and for the power of partnerships and collaborations between public and private organizations and service providers, resulting in the acknowledgment of new health care loci and professional performance (Tahan, 2020).

In the scenario studied, this was clearly due to collective mobilization and strengthening of the team spirit in all instances, in addition to integration and partnerships with other strategic sectors to enhance health care and management. That initiative was recurrent in several settings around the world, understanding that the health sector alone would be responsible for responding to the magnitude of the public health problem.

Several reports highlight the relevance of integration with universities through scientific research and extension/graduate projects, especially the Residency in Health Program, presenting a valuable method to qualify health care and increase access with the students' integration into the service. Several countries adopted this strategy, for example: the USA incorporated general surgery residents in the front line of the fight against COVID-19 (He et al., 2020), and Vietnam and England even integrated medical undergraduate students into health teams, resulting in more local human resources and contributing to people’s screening and dissemination of health information and policies necessary for the community (He et al., 2020) (Minh et al., 2021).

The reports evidenced the relevance of PHC in the pandemic, materialized through the managers' decision to extend the BHUs' opening hours and offering a chat channel to serve the community, in order to increase access and allow for timely identification of cases in addition to implementing 24/7 monitoring of the confirmed cases. Strengthening of the health system, with the first access mainly at the PHC level and based on health surveillance actions, has a direct impact on actions to control and face the pandemic. The experiences reported in the Iranian health system showed the intensification of screening of people at their homes or at the nearest BHUs, which operate for up to 16 hours/day, in addition to daily monitoring of people by a health care professional in each territory, enabled a rapid response in cases of symptomatic individuals, contributing to mitigating contagion (Hammad et al., 2019). Similar strategies were also adopted by Vietnam and Yemen (Minh et al., 2021) (Al Serouri et al., 2021).

Although the research findings do not extensively highlight the organization and provision of care to populations living in rural areas (land, river, and riverside) or even immigrants and people living on the streets, managers cited different strategies, developed in partnership with other institutions: the creation of collective housing, providing health care, isolation of infectious people, and monitoring of signs of aggravation (Lima et al., 2022).

The managers emphasize the dichotomy between state and municipal management, representing a tension point in functioning and organization of the HCN in the municipality. Shared management between the spheres emerged as a strong recommendation to strengthen the health system and control the pandemic in Manaus. Management communication problems were experienced in several national and international scenarios, with the learning that successful management in the pandemic requires continuous development of human resource skills, promotion of international knowledge, and timely information exchange between those involved in all health care levels (Túri & Virág, 2021). When working with high-risk issues, it is fundamental to consider how to implement an approach of systems and a change strategy that not only mitigates or prevents worsening of the scenario but also seeks to improve health care access and promote continuity in the entire health system and not only part of it. It is necessary to establish a cause and effect relationship; supply, demand, political goodwill, prejudice, and the social determinants of health underlie this analysis (Alejandro, 2021).

Studies address the importance of analyzing system safety management, not just as a set of rules and procedures, but based on variability, from a resilience engineering perspective, looking for timely and continuous performance adjustments made by health professionals to meet the demands of the population and cope with the unexpected. This approach facilitates the understanding and management of safety in complex systems, especially pandemics (Black et al., 2022).

Experiences such as those in the United Kingdom, aimed at the application of a system modeling approach to provide an understanding of how to improve responses to pandemic emergencies based on the current experience, confirm the importance of strengthening resilience in the practice of health care systems in complex situations. The learning based on experiences in the services during the confrontation with the pandemic of COVID-19 becomes urgent (Slater et al., 2022).

Health systems should seek resilience design, with a focus on protecting human life and promoting good collective health during and after the crisis (resilience dividend), improving performance (short term), and strengthening resilience (long term), with a focus on: updated mapping of human, physical, and information resources, identifying areas of strength, vulnerability, and potential health threats (biological and non-biological); strong epidemiological surveillance with predictive modeling; universal health coverage with provision of a broad range of services and protection for vulnerable families; self-regulation, with the ability to contain/isolate health threats and maintain basic services; integration, with information sharing, clear communication, and coordination of multiple actors (private sector, non-governmental organizations, local community leaders, and civil society); strong external connections with regional and global partners, maximizing available resources (Kruk et al., 2015).

The pandemic clearly brought about changes in the ways of being (stance) at all health care levels, causing changes in individual and even collective behaviors, in the solidarity and humanitarian sense.

With regard to the more technical aspects, the most remarkable lesson learned was related to the hygiene measures, both in the workplace and with regard to individual precautions when leaving work and before making contact with family members and friends. A study showed that this behavior had an indirect impact on the significant reduction in the number of respiratory syncytial virus infections worldwide, showing the importance of the continuous adoption of these habits by the employees for public health (Gastaldi et al., 2021).

Regardless of the specialty or function at that moment, physicians who worked in urgencies and emergencies stood out in the attempt to save lives, a surprising situation in the health system. Similar situations took place all over the world, such as in Iran, which redirected all the medical specialties and sub-specialties offered in the reference hospitals to COVID-19 management (Moini et al., 2021). Mathematical models to reorganize the workforce were also studied, as well as strategies such as alternating medical teams to enhance productivity and protection (Sánchez-taltavull et al., 2021).

The findings reveal an improvement in the collaborative spirit and in the care for others, contributing to a healthier work environment, even in crisis and stressful scenarios (Heath et al., 2020).

The leading role of some professionals in the workplace was noticed, showing resilient leadership and having a direct impact on the way of producing health in that locus.

Others offered support through spirituality, promoting spaces for reflection and collective shelter for those who sought or needed these moments in the service. All these individual initiatives proved to be valuable to help deal with feelings and anxiety in the pandemic. There are reports of health care professionals in the front line against COVID-19 who were able to take active measures to create a positive mindset and reflect about the meaning of their work, adopting self-care behaviors (Brown et al., 2021); although there is a warning about the increases in the levels of exhaustion, risks, and psychiatric diseases, it is not yet possible to estimate the long-term impacts on the workforce, including willingness to continue working in the field and shortage of professionals, especially physicians and nurses (Wilensky, 2022).

The reports also disclose the reflections about attributing a new meaning to the value of life, grief, and death; how to see the world; and what is actually deemed important in the everyday routine (Catania et al., 2021). Pandemics lead to behavioral changes and collective learning, having an influence on perceptions and actions such as sustainability (Weder et al., 2022), self-construal, and time framing, which mediate communication efficacy (Gong et al., 2022). The pandemic brought the invisible to light, both in society and in people, reverberating in each individual’s subjectivity, in valuable lessons for the entire world (Schwarcz & Starling, 2020).

The current study allows for an in-depth reflection on the managers' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was limited to reports collected in 2020; there is a need to conduct studies aiming to analyze the experiences from other moments of the pandemic.

Conclusion

This study describes the valuable repercussions and legacy resulting from the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the importance of strengthening the team spirit in service and establishing partnerships with public and private institutions from different sectors, especially the training in complex situations, while searching for strategies to mitigate the health crisis.

In addition to the repercussions described in terms of individual, team, and innovation incorporation strategies, three other categories make explicit the legacy that managers report as “lessons learned.” These lessons are not limited to objective dimensions of management or the work process, but have repercussions on the ways of being and the values involved in work. As a whole, the categories give an image of the legacy of coping with the pandemic for managers and the Unified Health System, meeting the objective of the study.

It was possible to show the importance of strengthening PHC, with innovative strategies to increase access standing out, such as differentiated opening hours, offering chat channels, and 24/7 monitoring of cases.

Many professionals assumed a leading role in the team, fostering a spirit of solidarity, care and listening to others, and support through spirituality, in addition to reflections on the meaning of work, life, and values.

The study can potentially contribute to qualifying and strengthening health managers in the face of health emergencies, due to the lessons learned mentioned in the reports. For this, it is fundamental to articulate individual and collective experiences, in terms of changes and ways of resistance and reorganization, both in the services and among professionals who face challenges and feel the impacts on their practices, feelings, and capabilities.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: Amazonas Research Foundation (FAPEAM), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development–CNPq Brazil. “This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001.”

ORCID iDs

Kassia Janara Veras Lima https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8952-5927

Marcus Vinicius Guimaraes de Lacerda https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3374-9985

Wagner Ferreira Monteiro https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3303-3031

Darlisom Sousa Ferreira https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3381-1304

Lucas Lorran Costa de Andrade https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7924-0538

Flavia Regina Souza Ramos https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0077-2292

References

- Alejandro J. (2021). Considering case management practice from a global perspective. Professional Case Management, 26(2), 99–103. 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Serouri A. A., Ghaleb Y. A., Al Aghbari L. A., Al Amad M. A., Alkohlani A. S., Almoayed K. A., Jumaan A. O. (2021). Field epidemiology training program response to COVID-19 during a conflict: Experience from Yemen. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–8. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.688119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amazonas. (2020. a). Amazonas state health plan 2020-2023. http://www.saude.am.gov.br/docs/pes/pes_2020–2023_ver_ini.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Amazonas. (2020. b). State contingency plan for human infection by the new coronavirus (COVID-2019). semsa.manaus.am.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PLANO-CONTINGENCIA_CORONAVIRUS_PARA-O-AMAZONAS.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Amazonas Health Surveillance Foundation. (2021). Covid-19 daily bulletin on Amazonas 02/06/2022. [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti. (2019). ATLAS.ti: The qualitative data analysis & research software. http://www.atlasti.com [Google Scholar]

- Black N. L., Tremblay M., Ranaivosoa F. (2022). Different sit:stand time ratios within a 30-minute cycle change perceptions related to musculoskeletal disorders. Applied Ergonomics, 99, 103605. 10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L., Haines S., Amonoo H. L., Jones C., Woods J., Huffman J. C., Morris M. E. (2021). Sources of resilience in frontline health professionals during COVID-19. Healthcare, 9(12), 1699. 10.3390/healthcare9121699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania G., Zanini M., Hayter M., Timmins F., Dasso N., Ottonello G., Aleo G., Sasso L., Bagnasco A. (2021). Lessons from Italian front-line nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(3), 404–411. 10.1111/jonm.13194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DATASUS. (2020). Brazilian institute of geography and statistics. https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/am/manaus.html [Google Scholar]

- Decree No. 7508 of June 28, 2011. Regulates Law No. 8080, of September 19, 1990, to provide for the organization of the Unified Health System - SUS, health planning, health care and interfederative articulation, and gives other measures. (2011). Federal Official Gazette of 06/29/2011. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2011/decreto/d7508.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldi A., Don D., Barbieri E., Giaquinto C., Bont L. J., Baraldi E. (2021). COVID-19 lesson for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV): Hygiene works. Children, 1–9(12), 1144. 10.3390/children8121144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H., Huang M., Liu X. (2022). Message persuasion in the pandemic: U.S. and Chinese respondents’ reactions to mediating mechanisms of efficacy. International Journal of Communication, 16(20), 840–863. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/17839 [Google Scholar]

- Hammad M. A., Sulaiman S. A. S., Aziz N. A., Noor D. A. M. (2019). Iran’s experience in controlling and managing COVID-19: A lesson for developing countries. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 24(1), 2020–2021. 10.4103/jrms.JRMS [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K., Stolarski A., Whang E., Kristo G. (2020). Addressing general surgery residents’ concerns in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Surgical Education, 77(4), 735–738. 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath C., Sommerfield A., von Ungern-Sternberg B. S. (2020). Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Anaesthesia, 75(10), 1364–1371. 10.1111/anae.15180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M. E., Myers M., Varpilah S. T., Dahn B. T. (2015). What is a resilient health system? Lessons from ebola. Lancet, 385(9980), 1910–1912. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law No. 8,080 of September 19, 1990. Provides for the conditions for the promotion, protection and recovery of health, the organization and operation of the corresponding services and other measures. (1990). Federal Official Gazette of 09/20/1990. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l8080.htm [Google Scholar]

- Lima K. J. V., Lacerda M. V. G. de, Monteiro W. F., Ferreira D. S., Andrade L. L. C. de, Ramos F. R. S. (2022). Technical-assistance arrangements in coping with the COVID-19 pandemic from the managers’ perspective. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 30, Article e3591. 10.1590/1518-8345.5799.3591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manaus. (2020). Municipal contingency plan for human infection by the new coronavirus. http://semsa.manaus.am.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Plano-de-Contingência-Municipal-para-Infecção-Humana-pelo-novo.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Minh L. H. N., Khoi Quan N., Le T. N., Khanh P. N. Q., Huy N. T. (2021). COVID-19 timeline of Vietnam: Important milestones through four waves of the pandemic and lesson learned. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–4. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.709067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moini A., Maajani K., Omranipour R., Zafarghandi M.-R., Aleyasin A., Oskoie R., Alipour S. (2021). Residency training amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the impact on mental health and training, a lesson from Iran. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12909-021-03029-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos F. R. S., Lacerda M. V. G., Ferreira D. S., Lima K. J. V., Tavares I. C., Monteiro W. F., Martins C. M. de G., Silva G. L. A. T. d., Andrade L. L. C. d., Monteiro W. M. (2020). Health work in the context of a pandemic: For a research agenda. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 53, Article e20200427. 10.1590/0037-8682-0427-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino E. C., Buss L. F., Carvalho M. P., Prete C. A., Crispim M. A., Fraiji N. A., Faria N. R., Parag K. V., da Silva Peixoto P., Kraemer M. U. G., Oikawa M. K., Salomon T., Cucunuba Z. M., Castro M. C., de Souza Santos A. A., Nascimento V. H., Pereira H. S., Ferguson N. M., Pybus O. G. (2021). Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet, 397, 452–455. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. In Seaman J. (Ed.), Qualitative research in organizations and management: An international journal (2nd ed.). SAGE. 10.1108/qrom-08-2016-1408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-taltavull D., Castelo-szekely V., Candinas D., Roldán E., Beldi G. (2021). Modelling strategies to organize healthcare workforce during pandemics: Application to COVID-19. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 523, 110718. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarcz L. M., Starling H. M. (2020). The ballerina of death; the Spanish flu in Brazil. Letter Company. [Google Scholar]

- Slater D., Hollnagel E., MacKinnon R., Sujan M., Carson-Stevens A., Ross A., Bowie P. (2022). A systems analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic response in the United Kingdom – Part 1 – the overall context. Safety Science, 146(2009), 105525. 10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahan H. M. (2020). Essential case management practices amidst the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis: Part 2: End-of-life care, workers’ compensation case management, legal and ethical obligations, remote practice, and resilience. Professional Case Management, 25(5), 267–284. 10.1097/NCM.0000000000000455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet. (2020). COVID-19: Learning from experience. Lancet, 395(10229), 1011. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30686-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Túri G., Virág A. (2021). Experiences and lessons learned from COVID-19 pandemic management in South Korea and the V4 countries. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 6(4), 201. 10.3390/tropicalmed6040201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weder F., Yarnold J., Mertl S., Hübner R., Elmenreich W., Sposato R. (2022). Social learning of sustainability in a pandemic — changes to sustainability understandings, attitudes, and behaviors during the global pandemic in a higher education setting. Sustainability, Março, 14(6), 2–18. 10.3390/su14063416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky G. R. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and the US Health Care Workforce. JAMA Health Forum, 3(1), 229–236. 10.1177/1062860617738328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R. K. (2014). Case study: Planning and methods (5th ed.). Bookman. [Google Scholar]