Abstract

Introduction

Active sacroiliitis represents the hallmark of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) and manifests as inflammatory low back pain associated with morning stiffness (MS). Sometimes, the combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and biological disease modifying drugs (bDMARDs) proves unsatisfactory in achieving a remission.

Materials and methods

We enrolled patients affected with active sacroiliitis confirmed via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and treated with a corticosteroid sacroiliac joint injection (SIJI) via ultrasound guidance.

After SIJI, we evaluated visual–analogue scale (VAS) and MS pain changes. As controls, we selected axSpA patients starting bDMARDs.

Results

We enrolled 26 patients (mean age 55 ± 14 years; 25 females and 1 male; > 95% treated with NSAIDs; 46% on bDMARDs; 75.82 ± 123 months) and examined a total of 47 treated joints. We detected a 48% reduction in VAS pain after 24 h. Moreover, we observed a significant reduction (p < 0.0001) of VAS pain between the baseline and every subsequent follow-up visit. Further, a significant difference in VAS pain compared to the baseline in the controls was observed starting from week 12. There was a significant reduction in MS after 1 week due to SIJIs, while in the controls the first significant change from the baseline in MS was detected after 12 weeks. The efficacy of infiltrative therapy lasted up to 6 months: persistent VAS as well as MS pain reduction was observed.

Conclusions

US-guided SIJI represents an effective and safe technique for patients who have active sacroiliitis yet are ineligible for biologic treatment or who experience unsatisfactory disease control despite receiving therapy.

Keywords: Active sacroiliitis, Sacroiliac joint injections, AxSpa, Pain, Morning stiffness, Ultrasound

Introduction

Inflammatory involvement of the sacroiliac joints (SIJs) represents the hallmark of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) [1, 2] and clinically manifests as inflammatory low back pain associated with morning stiffness (MS). Active sacroiliitis impairs patients’ quality of life, often leading to an increase in disability and an overall well-being reduction. Sometimes, even the full pharmacological regimen of the combination of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and biological disease modifying drugs (bDMARDs) proves unsatisfactory in achieving remission and/or low disease activity. Moreover, some patients may be ineligible to be treated with immunosuppressive therapy: it is well known among rheumatologists that an active infective disorder as well as an active neoplasia (or a history of a tumour that occurred within a period of less than 5 years) is incompatible with treatment with immunosuppressive compounds such as bDMARDs [3]. Corticosteroid injections represent a useful tool in rheumatological practice since they are successfully exploited in several clinical scenarios to achieve rapid and effective relief in inflammatory joint diseases such as knee osteoarthritis as well as mono- and oligoarthritis. Several papers affirm the effectiveness of SIJIs; however, most of the reported treatments exploit traditional fluoroscopy [4], computerized tomography [5], or MRI [6]. Although these techniques are reliable in terms of precision, they are burdened by intrinsic risks and limitations, such as radiation, invasiveness, and difficulty of use by obese and claustrophobic patients; moreover, they have high management costs and cannot be easily applied in an outpatient setting. In contrast, ultrasound (US), represents a low-cost and safe-to-use alternative that can be used to correctly visualize SIJs and therefore be applied when performing SIJIs. In this context, we conducted an observational real-life study aimed at establishing the efficacy of US corticosteroids sacroiliac joints infiltrations (SIJIs) in the treatment of active sacroiliitis in axSpA.

Anatomy of SIJ

Sacroiliac joints are diarthro–amphiarthrosis joints and unite iliac bones to the sacrum: they represent the pivot upon which the axial skeleton is supported. In the female gender, joint sliding movements increase the antero-posterior diameter of the pelvis, facilitating childbirth. SIJs can be didactically divided into a superficial and a deep portion: the fibrocartilaginous and capsule-ligamentous apparatus form the superficial portion, while the deep and caudal region where the auricular surfaces of the sacrum and the ileum bone make close contact represent the synovial part of the joint. Furthermore, the ligamentous apparatus can be divided into intrinsic and extrinsic categories. Among the former, we include the fibrous joint capsule, sacroiliac interosseous, anterior, and posterior ligaments (Fig. 1); the latter is composed of ilio-lumbar, sacrospinous, and sacrotuberous ligaments (Fig. 2). A clear knowledge of the anatomy of the sacroiliac joints is an essential prerogative for the musculoskeletal sonographer, both during diagnostic as well as invasive manoeuvres.

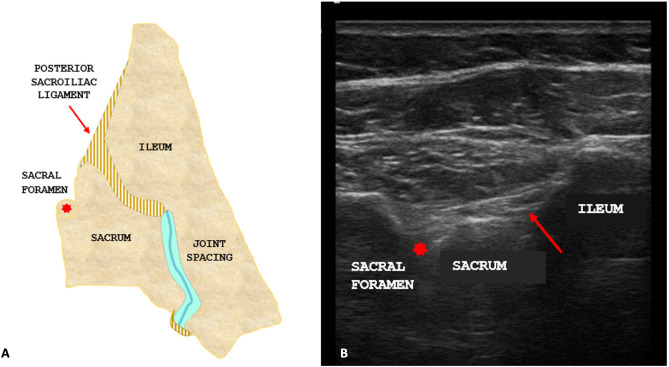

Fig. 1.

A Anatomical scheme of the posterior region of the right sacroiliac joint showing the short posterior sacroiliac ligament (superficial plane, red arrow) and the first dorsal sacral foramen (red asterisk). B Ultrasound scan of the posterior region of the right sacroiliac joint showing the short posterior sacroiliac ligament (superficial plane, red arrow) and the first dorsal sacral foramen (red asterisk)

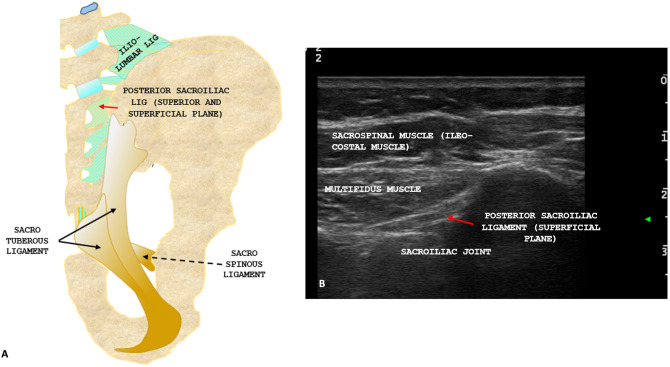

Fig. 2.

A Anatomical scheme of the posterior ligamentous apparatus showing intrinsic and extrinsic ligament with the short posterior sacroiliac ligament (superior and superficial plane, red arrow), the sacro-tuberous ligament (black arrow) and the sacro-spinous ligament (black dotted arrow). B Ultrasound anatomy of the posterior region of the sacroiliac joint with posterior sacroiliac ligament (superficial plane, red arrow)

Materials and methods

We enrolled patients affected by axSpA who had active sacroiliitis documented via MRI and treated them using a single SIJI of 40 mg of triamcinolone acetonide with US guidance (MyLabTwice®, Esaote, Genoa, Italy; convex array: 1–8 MHz). When indicated by clinical and radiological findings, we infiltrated both SIJs to reach an overall of 47 treated joints. Patients with stage IV sacroiliitis according to the modified New York criteria for axSpA were excluded beforehand. Pain visual-analogic scale (VAS) and MS data were collected at baseline, at 24 h, and at 48 h (only VAS) during the first, second, and fourth week, then every month until a follow-up of 6 months was reached. As a control group, we used patients from our arthritis clinic starting (or switching to) bDMARDs and already on NSAIDs.

Injection technique

Before the procedure, the infiltrative technique was explained to the patient and a written informed consent was obtained. Subsequently, the patient was placed in a prone position and an SIJ was identified using a probe. Thus, the needle entry site was identified and consequently marked using a dermographic pen. A US probe was sterilized and hooded using a dedicated sterile bag, then the patient’s skin was disinfected using iodopovidone and chlorhexidine. A dedicated sterile gel was employed as a sonographic interface. In the meantime, a 2.5 ml syringe was prepared and filled with 40 mg (1 ml) of triamcinolone acetonide onto which was loaded a spinal needle (Spinocan®, Braun, Melsungen, Germany) with a size of 20 G. The approach used was freehand medial-to-lateral, with the needle oriented at 45° toward the proximal and superficial part of SIJ (Fig. 3). The procedure involved crossing the posterior sacroiliac ligament with the needle and subsequently instilling a corticosteroid. Every injection was performed by a single experienced musculoskeletal sonographer who managed the probe and the needle. The sonographer was assisted by a colleague or a nurse. The present study was approved by a local ethical committee (protocol number 22271) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its late amendments.

Fig. 3.

Injection technique displaying the medial-to-lateral free hand approach

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Shapiro’s, Mann–Whitney’s, Kruskal–Wallis, Wilcoxon’s, Friedman’s, and Dunn’s tests to check normality and identify differences among tested variables. p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

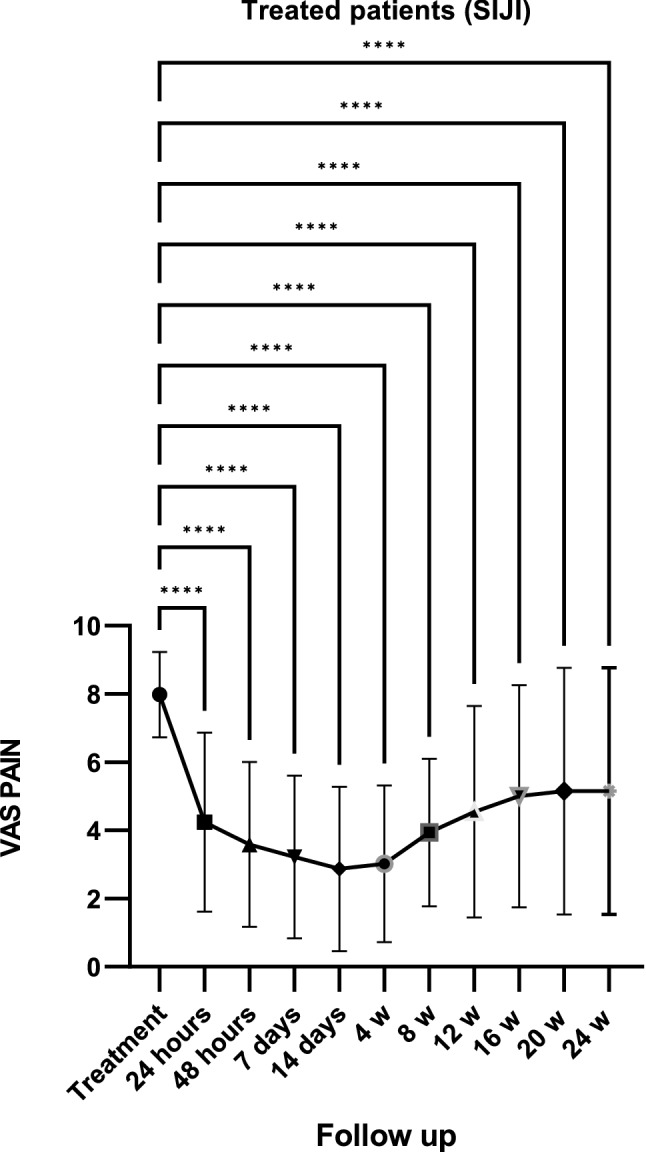

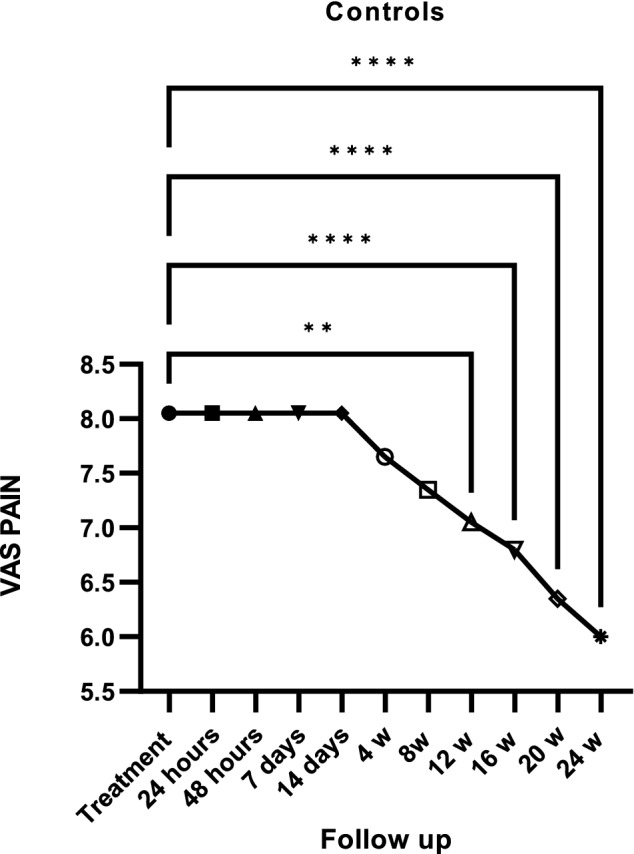

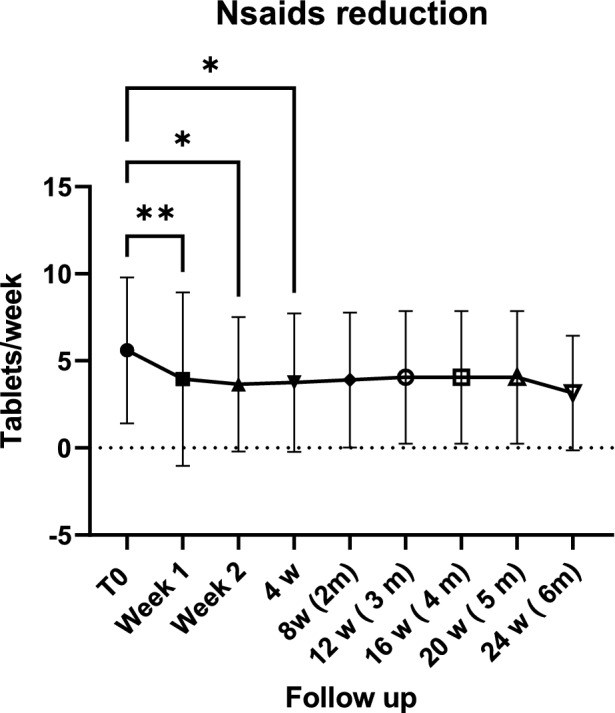

Twenty-six patients were treated (mean age 52.35 ± 15 years; 25 females and 1 male; > 95% treated using NSAIDs and 57% (15) using bDMARDs; 75.82 ± 123 months) using SIJI (Table 1). After 24 h, a reduction of 48% in VAS pain was documented. A high reduction (− 61%), expressed in percentage variation from SIJIs, was recorded 14 days after treatment. At every subsequent follow up, VAS pain was significantly lower than the baseline (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4). In the control group, a significant decrease in VAS pain was observed during the third month from the beginning of therapy (Fig. 5). There was a significant reduction in MS after 1 week due to SIJI (Fig. 6). Conversely, in the control group, the first significant change in MS was detected after 3 months of therapy (Fig. 7). The significant difference in VAS pain reduction between SIJI patients and controls was lost at the fifth month after injection. The efficacy of infiltrative therapy lasted up to 6 months. At the end of study, there was a persistent reduction of VAS pain (− 33%) as well as MS (− 64%) compared to the baseline, while no significant side effect was detected. Moreover, a reduction in the use of NSAIDs was documented (p < 0.05) after the procedure (Fig. 8).

Table 1.

Anthropometric and epidemiological features of patients

| SIJIs patients | Controls | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N° | 26 | 20 | n.a |

| M/F | 1/25 | 11/9 | n.a |

| Age | 52.35 ± 15 years | 57.65 ± 11 years | ns |

| Disease duration | 75.82 ± 123 months | 109.2 ± 71 months | p < 0.05 |

| Nsaids | > 95% | > 95% | n.a |

| bDmards | 46% (7 Ada, 3 Etn, 2 Gol, 1 Ctz, 1 Secu, 1 Apremilast) | 100% (11 Ada, 5 Etn, 3 Ctz, 1 Ifx) | n.a |

| VAS pain (baseline) | 7.97 ± 1.25 | 8.05 ± 1.68 | ns |

| MS (baseline) | 41.35 ± 20.52 | 45.75 ± 12.06 | ns |

N°: number of patients, M/F male/female, Nsaids non steroids inflammatory drugs, bDmards biological disease anti-modifying rheumatic drugs, VAS visuo-analogic pain scale, MS morning stiffness, ns not significant, n.a. not assessed

Fig. 4.

VAS pain reduction (Visuo-analogic pain scale) after SIJIs. Fig. = figure; ****p < 0.0001

Fig. 5.

VAS pain reduction (Visuo-analogic pain scale) in controls. Fig. = figure; ****p < 0.0001; **p < 0.05

Fig. 6.

Morning stiffness (MS) reduction after SIJIs. Fig.: figure; ****p < 0.0001

Fig. 7.

Morning stiffness (MS) reduction in controls. Fig. = figure; ****p < 0.0001; ***p = 0.003

Fig. 8.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (Nsaids) drug intake reduction after SIJIs. Fig.: figure; **p < 0.001; *p < 0.05

Discussion

Active sacroiliitis is a hallmark of axSpA and is associated with disability and a reduction in quality of life. Sometimes, a full regimen of NSAIDs and bDMARDs fails to cause low disease activity or remission, impairing patients’ quality of life. A recent review summarized the studies that evaluated SIJI and testified their efficacy although most of them considered fluoroscopy, MRI, or CT [7]. In the present research, the effect of US–SIJIs on active sacroiliitis was rapid in improving patients’ symptoms and in restoring a good quality of life. A previous study on using US to perform SIJIs demonstrated, through a fluoroscopic control, that the method had a high accuracy in reaching the synovial recess of a joint [8]. Indeed, the US–SIJI approach allows for aiming a target and following a needle during a procedure, thus increasing the accuracy and effectiveness of treatment. In our experience, 24 h after receiving SIJIs, patients reported a 48% overall reduction of VAS pain; in the control group, the first significant change in VAS pain was documented in the third month from the start of bDMARDs. The highest efficacy of SIJIs was reached 14 days after treatment, while VAS pain dropped by 61% after 2 weeks compared to the baseline. Moreover, VAS pain reduction in patients [9] undergoing infiltrative treatment lasted up to 6 months; and there was a persistent reduction of 33% at end of the study. We found similar results with MS: a significant pain reduction in the group of patients treated with SIJIs was documented after 7 days, and this reduction reached its highest level in the third month after the administration of SIJIs. Conversely, in controls, the effects of bDMARDs on MS became significant after the third month of therapy. Furthermore, a persistent reduction in MS was observed at the end of study compared to the baseline (− 64%), suggesting the lasting efficacy of SIJIs. Although these results are in line with the literature [5, 10, 11], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which has documented a rapid reduction in VAS pain and MS in association with their long lasting effects. The persistent reduction of the tested variables could be partially attributable to the bDMARDs therapy that 46% of our patients were undergoing at the time of study. Indeed, some of the treated patients were experiencing a secondary loss of efficacy of drugs at the time of SIJI. Although today’s rheumatologist’s armamentarium is composed of several bDMARDs for the treatment of axSpA, the careful use of drugs is always desirable: axSpA is a chronic disease which requires a life-time immunosuppressive regimen and several changes and bDMARD cycling. In addition, most of the infiltrated patients were being treated with a first or second-line anti-TNFα drug, which, to-date, is cheaper than anti-IL-17 compounds. Furthermore, several studies have, based on MRI, documented the efficacy of SIJI in reducing bone marrow oedema [12, 13]. Therefore, SIJIs may produce a disease modifier effect. Indeed, bDMARDs are effective compounds capable of modifying the course of disease and, in the last 30 years, have revolutionized the treatment of axSpA. Nevertheless, their effect is slow and requires a few months (3–6 months) before their benefit can be perceived by patients. In this study, the significant difference between the VAS pain experienced by SIJI patients and that experienced by the control group was lost at the fifth month (data not shown). Therefore, it could be argued that SIJIs are able to produce in a short time (24–48 h) effects that bDMARDs would take several months to produce. Moreover, a tumour history shorter than 5 years as well as the presence of active neoplasia and infections still represent an absolute contraindication to the use of bDMARDs. Therefore, treating patients with such a history is a challenge in everyday clinical practice for the rheumatologist. In this study, 3/26 subjects who could not be treated using a bDMARD due to an active neoplasia or a history of neoplasms shorter than 5 years had a marked improvement in quality of life following a SIJI. Further, NSAIDs represent the cornerstone for treatment of axSpA [14]: they should be used as a first-line therapy at the maximum dosage for at least 3 months to obtain clinical benefits. NSAIDs may also be continued after the beginning of use of bDMARDs if clinical practice requires it. Nevertheless, dangers to the use of NSAIDs are compounded by several risks, such as gastrointestinal as well as cardiovascular and renal impairment [9]. Thus, NSAIDs should always be used with caution—especially in fragile patients. A previous paper failed to identify a significant reduction of NSAID intake after SIJIs [11]. However, we observed a significant reduction of NSAID weekly intake in injected patients. The intake reached significance soon after baseline observation (p < 0.05).

Study limitations

The present study has several limitations. Given its real-life nature, the baseline disease duration difference may have influenced results. Indeed, the patients who received injections were those experiencing strong daily activity limitations due to axSpA symptoms. Thus, in this subset of patients with a low disease duration, SIJIs may have produced a superior result. The presence of a placebo-controlled group would have enhanced the quality of evidence collected in this paper. Furthermore, no control with MRI was performed after treatment. An MRI could have documented the real effectiveness of SIJIs and modifications in bone marrow oedema, if any. The absence of further clinical and laboratory variables did not allow a precise evaluation of disease activity. Moreover, due to the study’s real-life nature, our cohort displayed a high heterogeneity. Nevertheless, this latter limitation is also perceivable as the main strength of this paper: we documented that SIJIs could benefit patients experiencing heterogeneous disease stages using a compound undergoing loss of efficacy.

Conclusions

In the present study, we proved that US–SIJI is safe and effective in reducing pain and improving axSpA patients’ quality of life. We believe that US should be the preferred imaging tool to guide SIJI as it is a safe technique to reach a SIJ.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors deny any conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors deny any funding.

Ethical Statements

The present study was approved by a local ethical committee (protocol number 22271) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its late amendments.

Informed consent

The infiltrative technique was explained to the patient and a written informed consent was obtained.

Consent to publish

Each patient provided written informed consent to be enrolled.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rudwaleit M, Van Der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudwaleit M, Van Der Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantini F, Nannini C, Niccoli L, et al. Guidance for the management of patients with latent tuberculosis infection requiring biologic therapy in rheumatology and dermatology clinical practice. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouad AZ, Ayad AE, Tawfik KAW, et al. The Success Rate of Ultrasound-Guided Sacroiliac Joint Steroid Injections in Sacroiliitis: Are We Getting Better? Pain Pract. 2021;21:404–410. doi: 10.1111/papr.12967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Althoff CE, Bollow M, Feist E, et al. CT-guided corticosteroid injection of the sacroiliac joints: quality assurance and standardized prospective evaluation of long-term effectiveness over six months. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:1079–1084. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-2937-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fritz J, Henes JC, Thomas C, et al. Diagnostic and interventional MRI of the sacroiliac joints using a 1.5-T open-bore magnet: a one-stop-shopping approach. Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1717–1724. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendling D. Local sacroiliac injections in the treatment of spondyloarthritis. What is the evidence? Jt Bone Spine. 2020;87:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pekkafali MZ, Kiralp MZ, Başekim CÇ, et al. Sacroiliac joint injections performed with sonographic guidance. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:553–559. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harirforoosh S, Asghar W, F Jamali (2014) Adverse effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. J Pharm Pharm Sci (www.cspsCanada.org) 16(5):821–847 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ramírez Huaranga MA, Castro Corredor D, Plasencia Ezaine AE, et al. First Spanish study on the effectiveness of ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injection in patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2022 doi: 10.1093/rap/rkac036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokar S, Kayhan Ö, Şencan S, Gündüz OH. The role of sacroiliac joint steroid injections in the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis. Arch Rheumatol. 2021;36:80–88. doi: 10.46497/ArchRheumatol.2021.8043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Günaydin I, Pereira PL, Fritz J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging guided corticosteroid injection of sacroiliac joints in patients with spondylarthropathy. Are multiple injections more beneficial? Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s00296-005-0008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira PL, Günaydin I, Trübenbach J, Dammann F, Remy CT, Kötter I, Schick F, Koenig CW, Claussen CD. Interventional MR imaging for injection of sacroiliac joints in patients with sacroiliitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(1):265–266. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Sepriano A, Regel A, Ciurea A, Dagfinrud H, Dougados M, van Gaalen F, Géher P, van der Horst-Bruinsma I, Inman RD, Jongkees M, Kiltz U, Kvien TK, Machado PM, Marzo-Ortega H, Molto A, Navarro-Compàn V, Ozgocmen S, Pimentel-Santos FM, Reveille J, Rudwaleit M, Sieper J, Sampaio-Barros P, Wiek D, Braun J. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):978–991. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]