Abstract

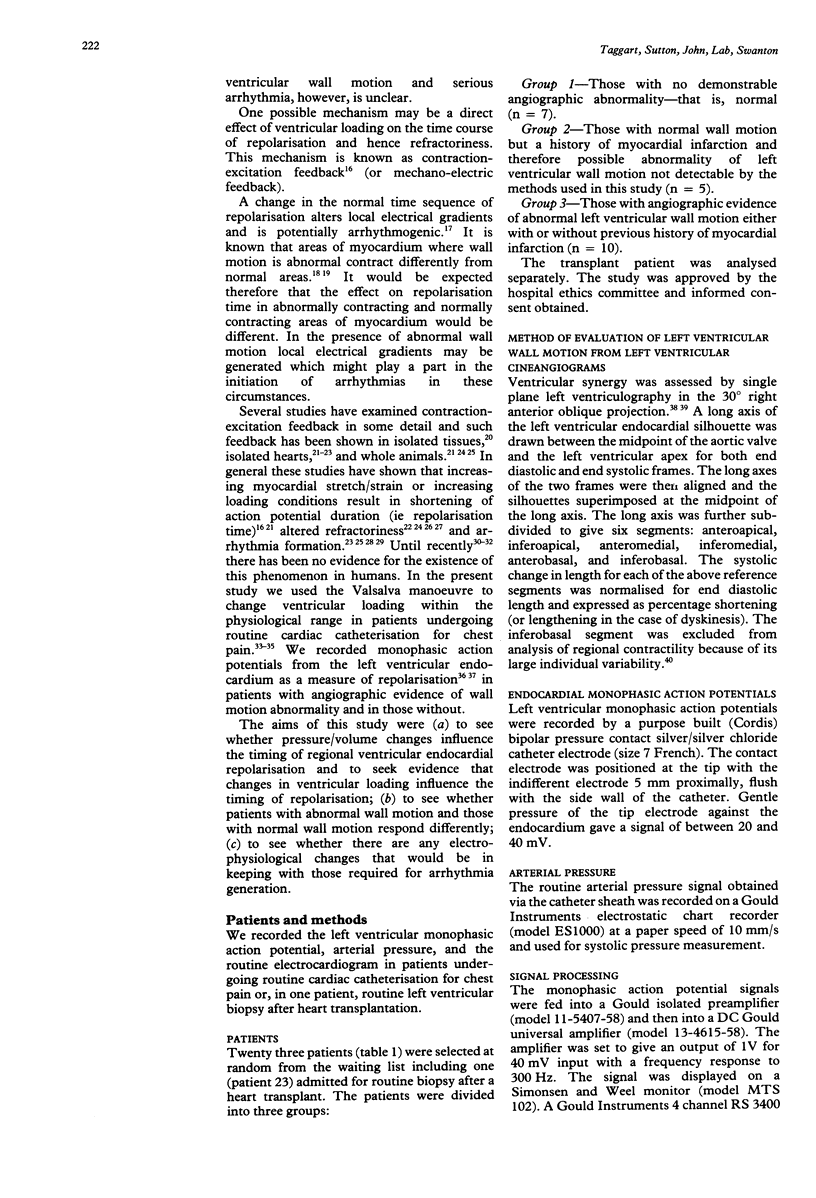

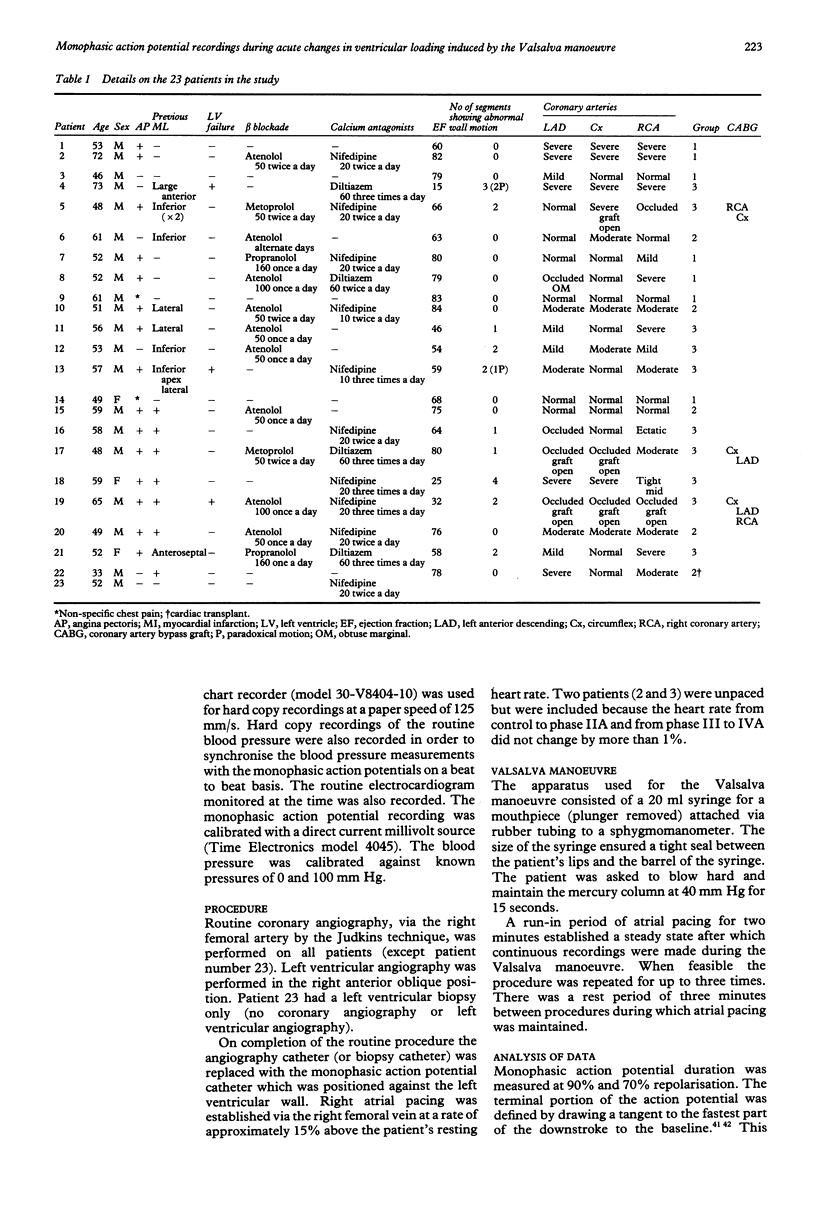

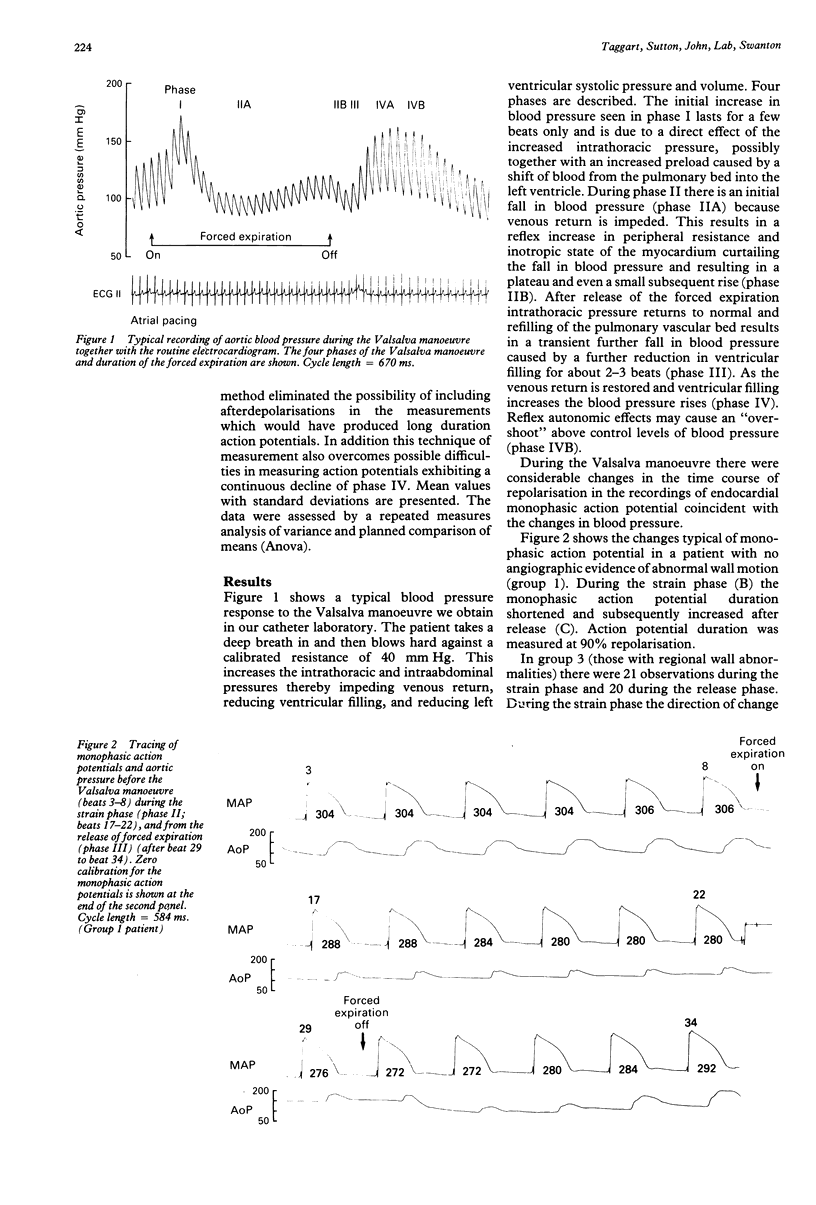

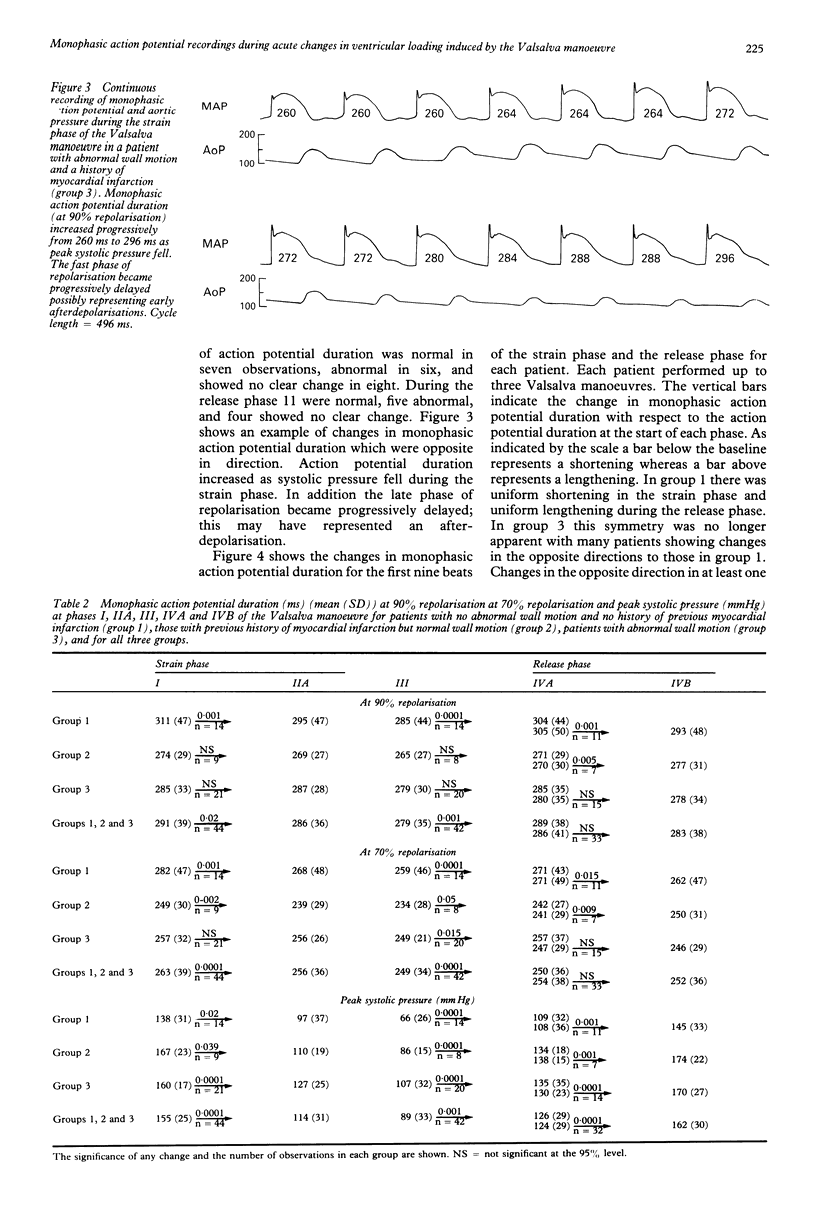

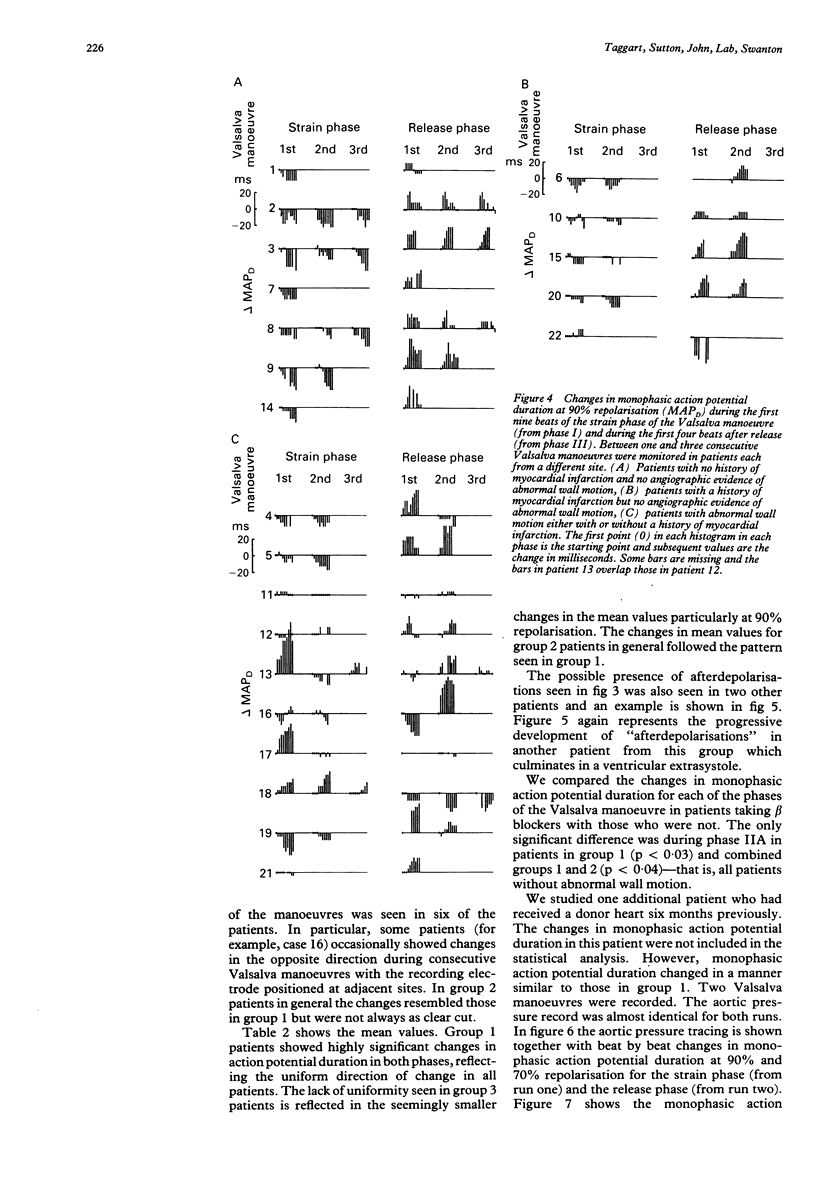

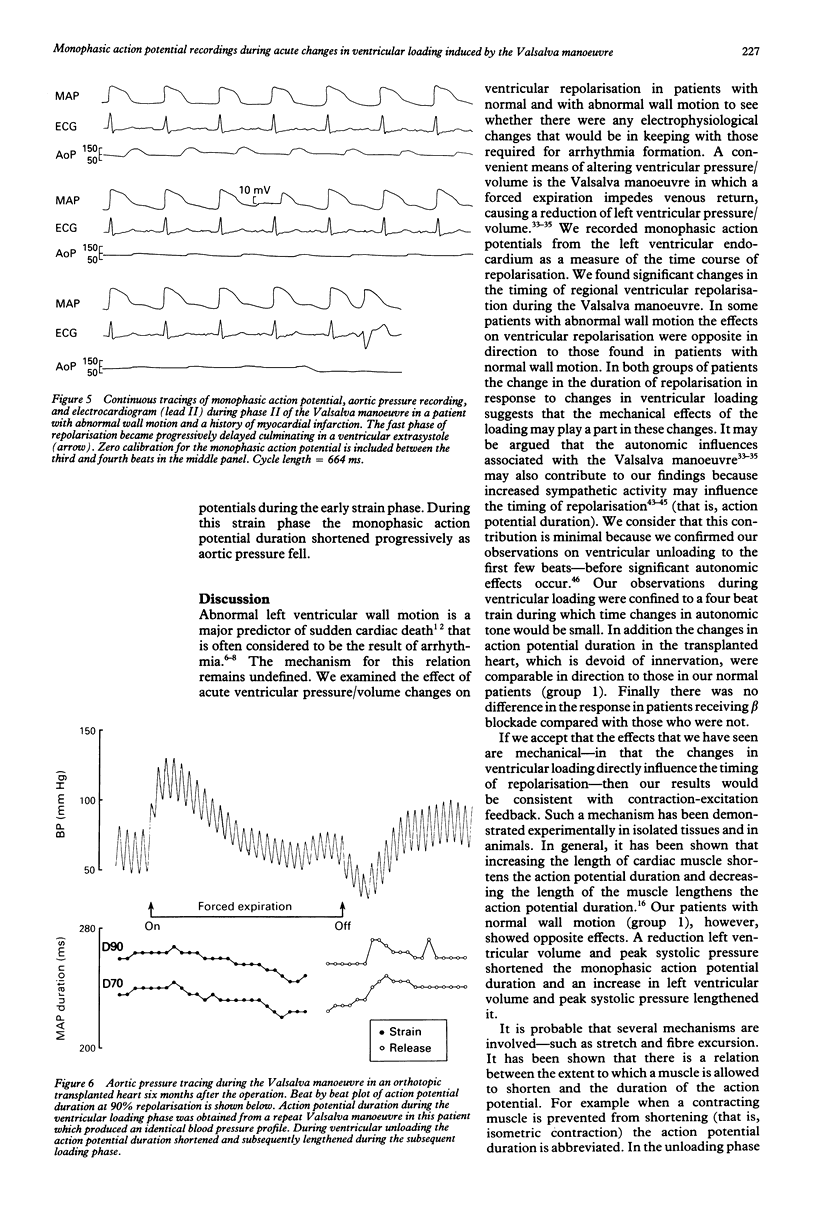

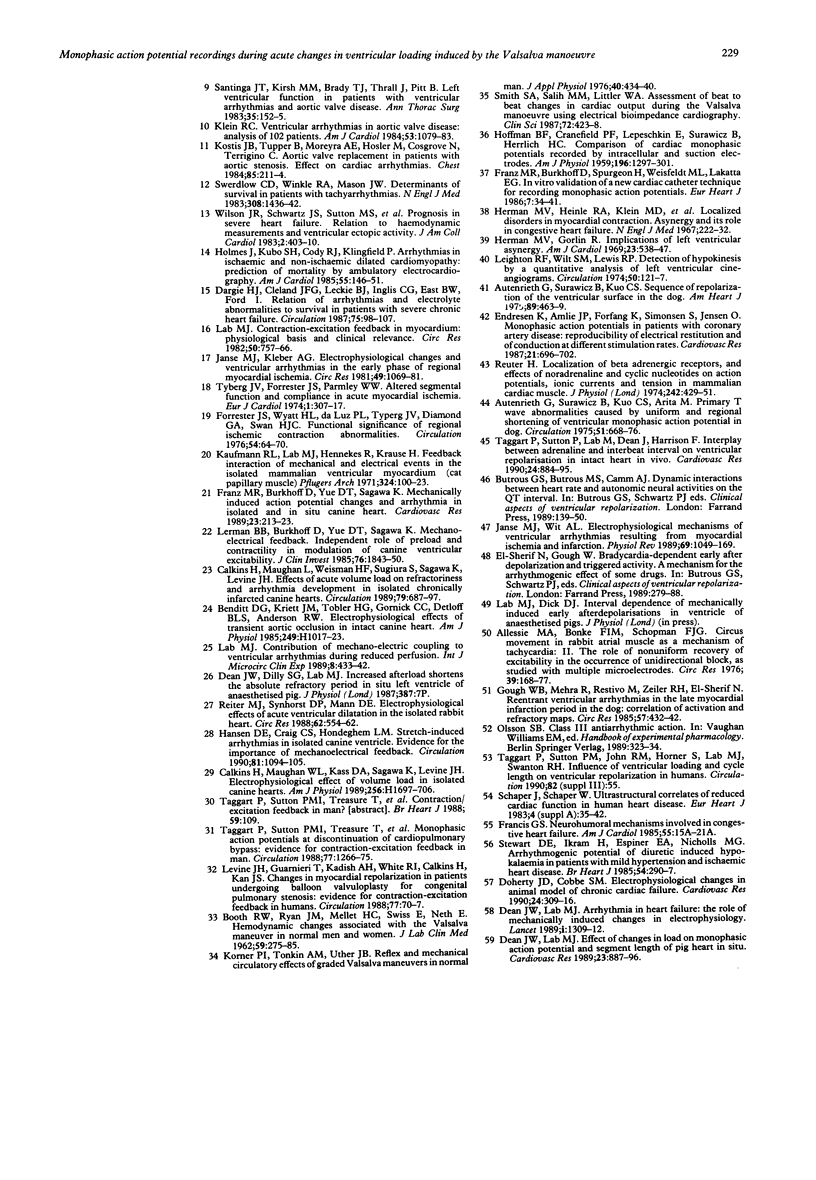

OBJECTIVE--The strong association between ventricular arrhythmia and ventricular dysfunction is unexplained. This study was designed to investigate a mechanism by which a change in ventricular loading could alter the time course of repolarisation and hence refractoriness. A possible mechanism may be a direct effect of an altered pattern of contraction on ventricular repolarisation and hence refractoriness. This relation has been termed contraction-excitation feedback or mechano-electric feedback. METHODS--Monophasic action potentials were recorded from the left ventricular endocardium as a measure of the time course of local repolarisation. The Valsalva manoeuvre was used to change ventricular loading by increasing the intrathoracic pressure and impeding venous return, and hence reducing ventricular pressure and volume (ventricular unloading). PATIENTS--23 patients undergoing routine cardiac catheterisation procedures: seven with no angiographic evidence of abnormal wall motion or history of myocardial infarction (normal), five with a history of myocardial infarction but with normal wall motion, and 10 with angiographic evidence of abnormal wall motion--with or without previous infarction. One patient was a transplant recipient and was analysed separately. SETTING--Tertiary referral centre for cardiology. RESULTS--In patients with normal ventricles during the unloading phase of the Valsalva manoeuvre (mean (SD)) monophasic action potential duration shortened from 311 (47) ms to 295 (47) ms (p less than 0.001). After release of the forced expiration as venous return was restored the monophasic action potential duration lengthened from 285 (44) ms to 304 (44) ms (p less than 0.0001). In the group with evidence of abnormal wall motion the direction of change of action potential duration during the strain phase was normal in 7/21 observations, abnormal in 6/21, and showed no clear change in 8/21. During the release phase 11/20 observations were normal, five abnormal, and four showed no clear change. In those with myocardial infarction four out of five patients had changes that resembled those with normal ventricles but the changes were less pronounced. There were no differences in any of the three groups between the changes in monophasic action potential duration in patients taking beta blockers and those who were not. The changes in monophasic action potential duration in the transplanted heart resembled those in the group with normal ventricles. Inflections on the repolarisation phase of the monophasic action potential consistent with early afterdepolarisations were seen in three of the patients with abnormal wall motion and in none of those with normal wall motion. CONCLUSIONS--These results are further evidence that changes in ventricular loading influence repolarisation. When wall motion was abnormal the effects on regional endocardial repolarisation were often opposite in direction to those when it was normal. Thus regional differences in wall motion could generate local electrophysiological inhomogeneity which may be relevant to the association of arrhythmia with impaired left ventricular function.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allessie M. A., Bonke F. I., Schopman F. J. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. II. The role of nonuniform recovery of excitability in the occurrence of unidirectional block, as studied with multiple microelectrodes. Circ Res. 1976 Aug;39(2):168–177. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autenrieth G., Surawicz B., Kuo C. S., Arita M. Primary T wave abnormalities caused by uniform and regional shortening of ventricular monophasic action potential in dog. Circulation. 1975 Apr;51(4):668–676. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.51.4.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benditt D. G., Kriett J. M., Tobler H. G., Gornick C. C., Detloff B. L., Anderson R. W. Electrophysiological effects of transient aortic occlusion in intact canine heart. Am J Physiol. 1985 Nov;249(5 Pt 2):H1017–H1023. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.5.H1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Califf R. M., Burks J. M., Behar V. S., Margolis J. R., Wagner G. S. Relationships among ventricular arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, and angiographic and electrocardiographic indicators of myocardial fibrosis. Circulation. 1978 Apr;57(4):725–732. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.57.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Califf R. M., McKinnis R. A., Burks J., Lee K. L., Harrell F. E., Jr, Behar V. S., Pryor D. B., Wagner G. S., Rosati R. A. Prognostic implications of ventricular arrhythmias during 24 hour ambulatory monitoring in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1982 Jul;50(1):23–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins H., Maughan W. L., Weisman H. F., Sugiura S., Sagawa K., Levine J. H. Effect of acute volume load on refractoriness and arrhythmia development in isolated, chronically infarcted canine hearts. Circulation. 1989 Mar;79(3):687–697. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert A., Lown B., Gorlin R. Ventricular premature beats and anatomically defined coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1977 May 4;39(5):627–634. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(77)80121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J. W., Lab M. J. Arrhythmia in heart failure: role of mechanically induced changes in electrophysiology. Lancet. 1989 Jun 10;1(8650):1309–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean J. W., Lab M. J. Effect of changes in load on monophasic action potential and segment length of pig heart in situ. Cardiovasc Res. 1989 Oct;23(10):887–896. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.10.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty J. D., Cobbe S. M. Electrophysiological changes in animal model of chronic cardiac failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1990 Apr;24(4):309–316. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.4.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endresen K., Amlie J. P., Forfang K., Simonsen S., Jensen O. Monophasic action potentials in patients with coronary artery disease: reproducibility and electrical restitution and conduction at different stimulation rates. Cardiovasc Res. 1987 Sep;21(9):696–702. doi: 10.1093/cvr/21.9.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester J. S., Wyatt H. L., Da Luz P. L., Tyberg J. V., Diamond G. A., Swan H. J. Functional significance of regional ischemic contraction abnormalities. Circulation. 1976 Jul;54(1):64–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.54.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R., Burkhoff D., Spurgeon H., Weisfeldt M. L., Lakatta E. G. In vitro validation of a new cardiac catheter technique for recording monophasic action potentials. Eur Heart J. 1986 Jan;7(1):34–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R., Burkhoff D., Yue D. T., Sagawa K. Mechanically induced action potential changes and arrhythmia in isolated and in situ canine hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1989 Mar;23(3):213–223. doi: 10.1093/cvr/23.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough W. B., Mehra R., Restivo M., Zeiler R. H., el-Sherif N. Reentrant ventricular arrhythmias in the late myocardial infarction period in the dog. 13. Correlation of activation and refractory maps. Circ Res. 1985 Sep;57(3):432–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOFFMAN B. F., CRANEFIELD P. F., LEPESCHKIN E., SURAWICZ B., HERRLICH H. C. Comparison of cardiac monophasic action potentials recorded by intracellular and suction electrodes. Am J Physiol. 1959 Jun;196(6):1297–1301. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1959.196.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D. E., Craig C. S., Hondeghem L. M. Stretch-induced arrhythmias in the isolated canine ventricle. Evidence for the importance of mechanoelectrical feedback. Circulation. 1990 Mar;81(3):1094–1105. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.3.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M. V., Gorlin R. Implications of left ventricular asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1969 Apr;23(4):538–547. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(69)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman M. V., Heinle R. A., Klein M. D., Gorlin R. Localized disorders in myocardial contraction. Asynergy and its role in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1967 Aug 3;277(5):222–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196708032770502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes J., Kubo S. H., Cody R. J., Kligfield P. Arrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: prediction of mortality by ambulatory electrocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1985 Jan 1;55(1):146–151. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse M. J., Kléber A. G. Electrophysiological changes and ventricular arrhythmias in the early phase of regional myocardial ischemia. Circ Res. 1981 Nov;49(5):1069–1081. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.5.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janse M. J., Wit A. L. Electrophysiological mechanisms of ventricular arrhythmias resulting from myocardial ischemia and infarction. Physiol Rev. 1989 Oct;69(4):1049–1169. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.4.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann R. L., Lab M. J., Hennekes R., Krause H. Feedback interaction of mechanical and electrical events in the isolated mammalian ventricular myocardium (cat papillary muscle). Pflugers Arch. 1971;324(2):100–123. doi: 10.1007/BF00592656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R. C. Ventricular arrhythmias in aortic valve disease: analysis of 102 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1984 Apr 1;53(8):1079–1083. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner P. I., Tonkin A. M., Uther J. B. Reflex and mechanical circulatory effects of graded Valsalva maneuvers in normal man. J Appl Physiol. 1976 Mar;40(3):434–440. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.40.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lab M. J. Contraction-excitation feedback in myocardium. Physiological basis and clinical relevance. Circ Res. 1982 Jun;50(6):757–766. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lab M. J. Contribution of mechano-electric coupling to ventricular arrhythmias during reduced perfusion. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1989 Nov;8(4):433–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton R. F., Wilt S. M., Lewis R. P. Detection of hypokinesis by a quantitative analysis of left ventricular cineangiograms. Circulation. 1974 Jul;50(1):121–127. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.50.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman B. B., Burkhoff D., Yue D. T., Franz M. R., Sagawa K. Mechanoelectrical feedback: independent role of preload and contractility in modulation of canine ventricular excitability. J Clin Invest. 1985 Nov;76(5):1843–1850. doi: 10.1172/JCI112177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J. H., Guarnieri T., Kadish A. H., White R. I., Calkins H., Kan J. S. Changes in myocardial repolarization in patients undergoing balloon valvuloplasty for congenital pulmonary stenosis: evidence for contraction-excitation feedback in humans. Circulation. 1988 Jan;77(1):70–77. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meizlish J. L., Berger H. J., Plankey M., Errico D., Levy W., Zaret B. L. Functional left ventricular aneurysm formation after acute anterior transmural myocardial infarction. Incidence, natural history, and prognostic implications. N Engl J Med. 1984 Oct 18;311(16):1001–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410183111601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter M. J., Synhorst D. P., Mann D. E. Electrophysiological effects of acute ventricular dilatation in the isolated rabbit heart. Circ Res. 1988 Mar;62(3):554–562. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.3.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. Localization of beta adrenergic receptors, and effects of noradrenaline and cyclic nucleotides on action potentials, ionic currents and tension in mammalian cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 1974 Oct;242(2):429–451. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Räsänen J., Nikki P., Heikkilä J. Acute myocardial infarction complicated by respiratory failure. The effects of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1984 Jan;85(1):21–28. doi: 10.1378/chest.85.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santinga J. T., Kirsh M. M., Brady T. J., Thrall J., Pitt B. Left ventricular function in patients with ventricular arrhythmias and aortic valve disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 1983 Feb;35(2):152–155. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)61452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper J., Schaper W. Ultrastructural correlates of reduced cardiac function in human heart disease. Eur Heart J. 1983 Jan;4 (Suppl A):35–42. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/4.suppl_a.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze R. A., Jr, Strauss H. W., Pitt B. Sudden death in the year following myocardial infarction. Relation to ventricular premature contractions in the late hospitals phase and left ventricular ejection fraction. Am J Med. 1977 Feb;62(2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. A., Salih M. M., Littler W. A. Assessment of beat to beat changes in cardiac output during the Valsalva manoeuvre using electrical bioimpedance cardiography. Clin Sci (Lond) 1987 Apr;72(4):423–428. doi: 10.1042/cs0720423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D. E., Ikram H., Espiner E. A., Nicholls M. G. Arrhythmogenic potential of diuretic induced hypokalaemia in patients with mild hypertension and ischaemic heart disease. Br Heart J. 1985 Sep;54(3):290–297. doi: 10.1136/hrt.54.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow C. D., Winkle R. A., Mason J. W. Determinants of survival in patients with ventricular tachyarrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jun 16;308(24):1436–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198306163082402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart P., Sutton P. M., Treasure T., Lab M., O'Brien W., Runnalls M., Swanton R. H., Emanuel R. W. Monophasic action potentials at discontinuation of cardiopulmonary bypass: evidence for contraction-excitation feedback in man. Circulation. 1988 Jun;77(6):1266–1275. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.6.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart P., Sutton P., Lab M., Dean J., Harrison F. Interplay between adrenaline and interbeat interval on ventricular repolarisation in intact heart in vivo. Cardiovasc Res. 1990 Nov;24(11):884–895. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.11.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyberg J. V., Forrester J. S., Parmley W. W. Altered segmental function and compliance in acute myocardial ischemia. Eur J Cardiol. 1974 Mar;1(3):307–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver W. D., Lorch G. S., Alvarez H. A., Cobb L. A. Angiographic findigs and prognostic indicators in patients resuscitated from sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 1976 Dec;54(6):895–900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.54.6.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H. D., Norris R. M., Brown M. A., Brandt P. W., Whitlock R. M., Wild C. J. Left ventricular end-systolic volume as the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1987 Jul;76(1):44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. R., Schwartz J. S., Sutton M. S., Ferraro N., Horowitz L. N., Reichek N., Josephson M. E. Prognosis in severe heart failure: relation to hemodynamic measurements and ventricular ectopic activity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983 Sep;2(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]