Abstract

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae infrequently causes genital tract infections but - in particular predisposing circumstances - it can be a transient part of vaginal flora and thus pelvic infections can occur.

Possible conditions associated with pneumococcal pelvic-peritonitis include the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices, recent birth and gynecologic surgery. The underlying mechanism of these occurrences is likely to be the ascending infection from the genital tract via the fallopian tubes.

Case presentation

We present a case of pelvic-peritonitis and pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in a healthy young woman wearing a menstrual endovaginal cup.

Following the radiological findings of a cystic formation in the right ovary and ascites effusions in all peritoneal recesses an emergency exploratory laparoscopy with right ovariectomy was performed. After resolution of abdominal sepsis, parenchymal consolidation complicated into necrotizing pneumonia, hence the patient underwent a right lower lobectomy.

Discussion

The menstrual cup is a self-retaining intravaginal menstrual fluid collection device, considered as a safe alternative to tampons and pads, which use is associated with rare adverse effects.

Few cases of infectious disease have been described, where the underlying mechanism may consist of bacterial replication within the blood accumulated in the uterine environment, with subsequent ascension into the genital tract.

Conclusion

In the rare occurrence of pneumococcal pelvic-peritonitis considering all possible infectious sources is paramount, as is assessing the possible involvement of intravaginal devices, increasingly used nowadays but of which potential complications are still poorly described.

Keywords: Pneumococcal pelvic-peritonitis, Menstrual cup, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Source control

Highlights

-

•

Pneumococcal peritonitis may derive from an ascending infection from genital tract.

-

•

Menstrual cup is a safe environmentally positive alternative to tampons and pads.

-

•

Few cases of infectious disease related to menstrual cup have been described.

-

•

We should consider its possible role in the pneumococcal peritonitis pathogenesis.

1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a gram positive bacteria that frequently cause pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis and carries a high burden of morbidity and mortality [1].

Although Streptococcus pneumoniae infrequently causes genital tract infections, as it is not part of the resident vaginal flora, in particular predisposing conditions - such as use of intrauterine contraceptive devices, recent delivery, or gynecological surgery - it can be a transient part of the vaginal flora, and thus pelvic infection can occur [2].

A menstrual cup is an endovaginal device made of silicon or rubber and is being increasingly used as an alternative to menstrual tampons. We present a case of pelvic-peritonitis and pneumonia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae in a healthy young woman wearing a menstrual cup.

This case has been reported following the SCARE Criteria [3].

2. Case presentation

After having obtained written informed consent, we present the case of a 42-year-old woman, who attended our emergency department with fever, abdominal pain occurring few days before, and dyspnea started the previous day. Her past medical history was relevant only for a cesarean section and appendectomy. She had a positive social background with a medium to high socioeconomic status and regular sex activity with the same partner.

Blood analysis revealed: elevated C-reactive protein >250 mg/l (reference values: 0,5–5 mg/l), procalcitonin 25,46 ng/ml (reference values: 0–0,5 ng/ml), leucocyte count of 11.6 × 10.3/mm^3 (reference values: 4–10 × 10^3/mm), abnormal renal function (creatinine 2,1 mg/dl), venous lactate 4.3 mmol/l (reference values: 0,5–2,2 mmol/l) and negative value of βHCG.

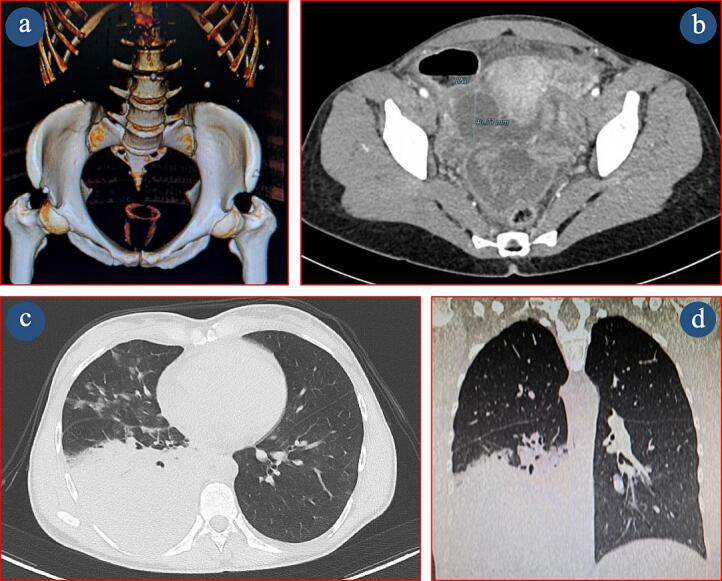

Chest CT scan showed large consolidation with air bronchogram completely involving the right lower lobe (Fig. 1c). Abdominal CT scan showed overdistension of the entire colic frame, ascites effusion in all peritoneal recesses and a cystic formation at the right ovary (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a: Abdominal CT scan show the presence of a menstrual endovaginal cup. Fig. 1b: Cystic formation at the right ovary and ascites effusion in the peritoneal recesses. Fig. 1c: Parenchymal consolidation with air bronchogram completely involving the right lower lobe. Fig. 1d: Progressive abscessualization of the right lobe parenchymal consolidation.

At the gynecological assessment, the patient was found to be using a menstrual cup on the fifth day of her menstrual cycle (Fig. 1a). After the device removal, speculoscopy was normal without leucorrhoea. A vaginal swab was carried out and commensal vaginal flora was observed. Transvaginal ultrasound confirmed the isoechoic cystic abscess on the right ovary.

In the suspicion of pelvic-peritonitis, with concurrent pneumonia, the patient was admitted to the Gynecology Department with an empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy including Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Azithromycin. Within hours from hospital admission, an emergency exploratory laparoscopy with right ovariectomy was performed. Due to the hemodynamic instability requiring vasopressors, respiratory failure, and acute kidney injury, at the end of the surgery the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit where she was maintained on mechanical ventilation and the antibiotic therapy was reinforced with Meropenem, Linezolid, Ciprofloxacin and Fluconazole.

Histological examination of the ovary showed an hemorrhagic pseudocyst, atresic corpus luteum and chronic suppurative salpingitis with fibrino-purulent peritonitis.

Culture tests of bronchoaspirate and intraoperative sample of peritoneal fluid led to the isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae, using matrix assisted laser desorption time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALD-TOF). The Streptococcus pneumoniae was sensitive to Levofloxacin, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, Vancomycin, Penicillin, Ceftriaxone, Cefotaxime, Amoxicillin, Imipenem.

Because of the progressive worsening of respiratory function in the post-operative period, a chest X-ray was performed which showed increased pleural effusion on the right side requiring placement of chest drainage. Over the following days vasopressor therapy was tapered and the renal function returned to normal. She was extubated on the 7th day and transferred to a medical ward on the 10th day.

A Follow-up CT scan showed progressive abscessualization of the right lobe parenchymal consolidation (Fig. 1d). The diagnosis of necrotizing pneumonia was confirmed at the subsequent CT investigation also, whereby a right lower lobectomy was performed.

The patient recovered rapidly during the following days and she was discharged on the 8th postoperative day, asymptomatic with a good performance status.

3. Discussion

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an acute infection of the upper genital tract structures in women, which may affect the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries.

PID is usually a polymicrobial infection, predominantly sexually transmitted. The pathogens generally involved in the development of PID are Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium [4].

Streptococcus pneumoniae frequently causes pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis and carries a high burden of morbidity and mortality but infrequently causes genital tract infections as it is not part of the resident vaginal flora [1]. However, in particular predisposing conditions, such as the use of an intrauterine contraceptive devices, recent birth and gynecological surgery, Streptococcus pneumoniae can be a transient part of the vaginal flora and may therefore be the trigger for pelvic infections [5].

In patients with an inserted intrauterine device, the underlying mechanism of PID is possibly an ascending infection from the genital tract via the fallopian tubes [6].

However, even without the above predisposing factors, several cases of Streptococcus pneumoniae primary peritonitis have been described [7]. The physiopathology of primary pneumococcal peritonitis remains unclear. Bacteria could access the peritoneal cavity by translocation from the intestinal tract, by hematogenous route from other infectious foci or, in females, by retrograde spread from the genital tract [8].

In our case, the abdominal onset of symptoms, concomitant with the beginning of the menstrual cycle and the use menstrual cup utilization, made us consider the possible genital source of infection.

The menstrual cup is a typically reusable, flexible, self-retaining intravaginal menstrual fluid collection device, considered as a safe, cost-effective and environmentally positive alternative to tampons and pads [9]. Its use is associated with low occurrence of adverse effects including possible vaginal pain or wounds, allergies or rashes, and rare urinary tract disorders [10]. Few cases of infectious disease related to the incorrect use of the menstrual cup or tampons have been described, most significant ones concern cases of Menstrual toxic shock syndrome (mTSS), a life-threatening condition caused by superantigen (TSST-1)-producing Staphylococcus aureus [11]. The pathophysiology of this syndrome is probably multifactorial, but the main mechanism consists of bacterial replication within the accumulated blood in the uterine environment, with subsequent ascension into the genital tract [12].

The treatment of PID consists of early empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage of probable pathogens and subsequent targeted therapy based on the antibiogram [13]. Exploratory laparoscopy represents, as in our case, a treatment option for most critical patients, as well as a means of obtaining a more accurate microbiological diagnosis, as suggested by latest guidelines [14].

Since delay in diagnosis and treatment can lead to severe and disabling inflammatory sequelae in the genital tract, it is of utmost importance to recognize the source of infection early on, also considering the possible implication of different risk factors, even those still poorly discussed.

4. Conclusions

Although haematogenous transmission from pulmonary focus may provide a plausible pathophysiological interpretation of our case, the exact mechanism can only be hypothesized. The abdominal presentation of the symptoms and the clinical evolution suggested the ascending pathogenesis of the infection.

In the rare occurrence of pneumococcal pelvic-peritonitis, considering all possible infectious sources is a cornerstone, as is assessing the possible involvement of intravaginal devices, increasingly used nowadays but whose possible complications are still poorly described.

Consent

We obtained verbal and written informed consent from the patient for this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

This study is exempted from ethical approval in our institution.

Funding

The authors have no sources of funding to declare for this manuscript.

Author contribution

AC and AF: Investigation and Resources;

AC and AF: Writing - Original Draft;

CF, MB, CC and VB: Review & Editing and Supervision.

Guarantor

Christian Compagnone.

Research registration number

Not applicable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alberto Calabrese: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Anna Fornaciari: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Christian Compagnone: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Maria Barbagallo: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Cinzia Fornaciari: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Valentina Bellini: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lemoyne S., Van Leemput J., Smet D., et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease due to streptococcus pneumoniae: a usual pathogen at an unusuak place. Acta Clin. Belg. 2008;63(6):398–401. doi: 10.1179/acb.2008.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larsen B., Monif G.R.G. Understanding the bacterial flora of the female genital tract. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;32(4):e69–e77. doi: 10.1086/318710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus Surgical Case Report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lis R., Rowhani-Rahbar A., Manhart L.E. Mycoplasma genitaliumInfection and female reproductive tract disease: a meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;61(3):418–426. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westh H., Skibsted L., Korner B. Streptococcus pneumoniae infections of the female genital tract and in the newborn child. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1990;12(3):416–422. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts S.C., Quinlan M.P., Galvin S.R. Disseminated Streptococcus pneumoniae infection associated with an intrauterine device. Infect. Dis. Clin. Pract. 2020;28(4):238–241. doi: 10.1097/ipc.0000000000000843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortese F., Fransvea P., Saputelli A., et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae primary peritonitis mimicking acute appendicitis in an immunocompetent patient: a case report and review of the literature. J. Med. Case Rep. 2019;13(1) doi: 10.1186/s13256-019-2038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monneuse O., Tissot E., Gruner L., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous group a streptococcal peritonitis. Br. J. Surg. 2009;97(1):104–108. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mouhanna J.N., Simms-Cendan J., Pastor-Carvajal S. The menstrual cup. JAMA. 2023;329(13):1114. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Eijk A.M., Zulaika G., Lenchner M., et al. Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(8):e376–e393. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(19)30111-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumann Christian, Kaiser Rene, Bauer Judith. Menstrual cup-associated toxic shock syndrome. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.12890/2020_001825. (LATEST ONLINE). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tierno P.M., Hanna B.A. Propensity of tampons and barrier contraceptives to amplify Staphylococcus aureus toxic shock syndrome toxin-I. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994;2(3):140–145. doi: 10.1155/s1064744994000542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yusuf H., Trent M. Management of pelvic inflammatory disease in clinical practice. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2023;19:183–192. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s350750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) - STI treatment guidelines. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/pid.htm Available from: